Compiled by Brent A. Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

The Allies’ Final Italian Landing—80 Years Ago

Although Operation Overlord is considered the most significant and largest amphibious landing of World War II, several noteworthy amphibious assaults also took place in Italy in the months leading up to the Allied assault on the beaches of northern France about six months later. The first was the landing on Sicily on July 10, 1943, and the second was the landing on the Gulf of Salerno on Sept. 9. The third and final landing on Italian soil during the war began in the early morning of Jan. 22, 1944. Codenamed Operation Shingle, it was a two-division amphibious assault near the coastal cities of Anzio and Nettuno, approximately 35 miles from German-occupied Rome. The Anzio landings were coupled with an attempted Allied breakthrough of the highly fortified Gustav Line from the south. More than 36,000 troops from a combined British and American landing force poured ashore on Italy’s western coast shortly after midnight. Initially, enemy resistance on shore was virtually nonexistent, consisting mostly of sporadic artillery fire. The amphibious assault completely surprised the enemy. In the weeks that followed, the number of Allied troops in the area would double in the push to liberate Italy.

For naval operations—which were aided by calm seas—the commencement of the operation went remarkably well. A fair number of enemy mines were cleared from the approach lanes despite the task force’s minesweepers having only a few hours to accomplish their mission. However, later that morning, minesweeper USS Portent (AM-106) became the first ship lost during the operation when it struck a mine and sank with the loss of 18 of the ship’s crew. British ship HMS Palomares also hit a mine but wasn’t sunk. Luftwaffe (German air force) antishipping attacks were also light, although a 500-pound bomb struck and sank landing craft LCI-20. USS Brooklyn (CL-40) and British cruisers HMS Penelope, Orion, and Spartan provided naval gunfire support for the few targets that were encountered on shore, and the Allied air forces flew more than 1,200 sorties to seal off the beaches and provide air cover for the disembarking convoys.

Although the operation was initially mostly uncontested, the Germans quickly deployed forces to the Italian coast, supplemented by increased air attacks on the Allies. The following day, German planes broke through Allied air cover and attacked British destroyers HMS Janus and Jervis with a combination of conventional and radio-guided bombs. A guided bomb damaged Jervis, but the ship suffered no casualties and withdrew from action. Janus later broke in half, capsized, and sank, with the loss of 159 of the crew. On Jan. 24, another series of enemy air attacks struck Allied shipping off Anzio. A bomb hit USS Plunkett (DD-441), killing 53 crew members and forcing the ship to withdraw. Although the ship was clearly marked, British hospital ship HMHS St. David was sunk, with approximately 100 killed. Just as German bombing runs subsided on that day, either a mine or a guided bomb caused an explosion on USS Mayo (DD-422) that killed five Sailors and knocked the ship out of action. The first three days of Operation Shingle were the costliest up to that point for Allied naval forces during the Italian campaign.

Throughout the operation, minesweeping and gunfire support continued. However, enemy mines would remain a problem. On Jan. 25, minesweeper YMS-30 struck a mine and sank, killing 17 American Sailors. The following day, HMS LST-422 hit a mine and began to burn. While attempting to help the British ship, landing ship LCI-32 also hit a mine and sank, losing 30 crew members. Off-loading at the beach was hampered by poor weather on Jan. 26, and the combination of German air raids and VI Corps’ slow and deliberate inland advance began to minimize the usefulness of naval gunfire support. Five bombing attacks resulted in two Liberty ships being knocked out of action, along with damage to seven patrol craft, a rescue tug, and HMS LST-366. Fortunately, the weather lifted the following day and off-loading continued. Enemy attacks continued as well. Guided bombs sank a third Liberty ship, Samuel Huntington, on Jan. 29, and a guided bomb sank British cruiser Spartan. Luftwaffe losses were also heavy, and after the Jan. 29 raid, a combination of smoke obscuration, anti-aircraft fire, Allied air superiority, and newly fielded anti-guided bomb jammers rendered German air raids much less effective. Further attacks sank Liberty ship Elihu Yale and landing craft LCT-35 on Feb. 15, killing 12, and a final successful attack on Feb. 25 sank destroyer HMS Inglefield, with a loss of 35 of the ship’s crew. However, the Luftwaffe proved unable to stop the task force from delivering troops and supplies to the Anzio beachhead.

Although intense fighting on the ground continued, the Navy’s most significant role in the operation was that of a logistical lifeline. At Naples, Fifth Army logisticians staged trucks that were preloaded with supplies on landing craft, allowing them to roll off the ships at Anzio and proceed to supply points on shore to off-load. Empty trucks stood by to embark on ships for the return voyage to Naples. The whole operation would repeat continuously. This system was credited with vastly speeding up the delivery of supplies and would turn out to be critical to the survival of Allied forces at Anzio. By the time the fighting ended, more than 500,000 tons of supplies had been delivered, a daily average of about 4,000 tons.

In May 1944, the fighting at the Anzio beachhead finally ended, and the Germans withdrew to the north of Rome. Rome fell to the Allies on June 4. Operation Shingle cost more than 23,000 British and American combat casualties, approximately 4,400 of whom were killed in action. At least 160 U.S. Navy personnel were killed at Anzio. Four months of continuous operations while exposed to actual or threatened enemy bombs, shells, and mines also took their toll, and many Sailors were evacuated as non-combat casualties. Although Operation Shingle was costly, it was important for the liberation of Italy and served as a precursor for the Normandy invasion. The landings at Anzio drew in German reinforcements from across Europe, weakening the forces that were slated to defend northern France. The long and bloody Allied campaign in Italy also contributed to the success of campaigns elsewhere in Europe.

The Boston Molasses Disaster

On Jan. 15, 1919, U.S. Navy Sailors in Boston Harbor on board training ship Nantucket and wooden-hulled barge Bessie J. (ID No. 1919) witnessed and played a key role in the recovery efforts in one of America’s most bizarre disasters. Earlier, in 1915, the United States Industrial Alcohol Company (USIA) built a 50-foot-wide, 90-foot-tall molasses tank on Commercial Street in Boston’s North End. The tank was capable of holding more than 2 million gallons. During that time, molasses was used to produce industrial alcohol for munitions and other weaponry. Over the years, workers and locals reported that the tank often rumbled, and it leaked frequently. On Jan. 12, 1919, steamer Miliero arrived in Boston Harbor and pumped about 600,000 gallons of warm molasses into the holding tank. Over the course of the next three days, the warm molasses reacted with the cold molasses already in the tank, accelerating fermentation and increasing pressure on the tank’s already weak walls. On the afternoon of Jan. 15, Gunner’s Mate Robert Johnston was about to sit down for lunch on Bessie J. when he heard a loud rumble and began yelling at his shipmates. Lt. Cmdr. Howard Copeland on Nantucket also heard the rumbling and watched the massive tank burst. Instantly, a tidal wave of 2.3 million gallons of molasses spilled down the streets of Boston’s North End, traveling 35 miles per hour with waves reaching at least 25 feet in height. The surge destroyed homes and swept railroad cars away. The steel supports for the city’s elevated train snapped, and people were tossed into the freezing harbor.

Immediately, Copeland issued a call to quarters, and more than 100 Sailors from Nantucket rushed to the accident. After posting guards to keep bystanders away from the wreckage, Sailors started digging through the rubble. Molasses literally covered everything. Sailors from Bessie J. joined in and waded through the knee-deep molasses while searching for survivors. By the time Boston police and firefighting crews arrived on the scene, Sailors had recovered six bodies and rescued more than 20 from the wreckage. After the first responders arrived, Sailors continued to rescue locals from the frigid harbor and others trapped inside their apartments. A steady stream of ambulances arrived to transport the wounded, including vehicles from the naval hospital in nearby Chelsea. Two tugboats and a patrol boat crossed the river from the Boston Navy Yard to provide additional transportation for the wounded.

Ultimately, the Boston Molasses Disaster took the lives of 21 people and injured another 150. Boston Harbor took on a brown hue for days afterward, and molasses continued to spread throughout the city. USIA quickly blamed anarchists in Boston’s largely Italian North End for the disaster, claiming an explosion rather than a weak tank was responsible for the incident. Years later, USIA was found to be responsible in a civil case and forced to pay $628,000 (more than $11 million today). Today, a plaque in Boston’s North End serves as a reminder of the tragedy that occurred 105 years ago. Some locals claim they still get whiffs of molasses on hot summer days.

Operation Desert Storm

On Jan. 17, 1991, combat air operations commenced in support of Operation Desert Storm. When the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait on Aug. 2, 1990, the United States deployed a major joint force as part of a multinational coalition to stop President Saddam Hussein’s brutal aggression. The U.S. Navy provided sea control and maritime superiority, which paved the way for the introduction of U.S. and allied air and ground forces. Saddam’s repeated refusal to abandon the invasion and leave Kuwait led to the commencement of combat operations. The subsequent bombardment by air assets and the effects of the economic embargo decimated Iraq’s military infrastructure and morale, degraded communications and supplies, and devastated weapons arsenals. During the initial period of the war, Navy ships launched salvos of Tomahawk cruise missiles against military targets in Iraq to “soften” the battlefield for ground troops. After the 38-day air campaign ended, ground troops began sweeping through Kuwait on Feb. 24, 1991, in blitzkrieg fashion. In a mere 100 hours, the Iraqi army was crushed. Iraqi soldiers surrendered by the thousands. Kuwait was free again.

In the aftermath of Desert Storm, coalition forces immediately turned from combat operations to humanitarian efforts. They sorted out refugees, assisted the Kuwaitis in reoccupying their cities, and helped them begin the long process of rebuilding. Civil affairs teams set up food, water, and fuel distribution points and medical clinics. The long struggle of reconstruction had just begun. For the Navy, Desert Storm improved its ability to contribute to multinational and joint-service operations against enemies both on land and sea. After the war, U.S. Naval Forces Central Command (NAVCENT) gained significant operational experience working on the international effort to restore Kuwait’s infrastructure, clear the Persian Gulf of mines, maintain maritime patrols against Iraq, and deter Saddam’s activities. The Navy’s role in “no-fly” zones over Iraq, launch of Tomahawk strikes against military targets in 1993, and fleet movements in 1994 helped—temporarily—to restrain Saddam’s ambitions. The Navy worked diligently to assure friendly nations in the Persian Gulf that U.S. forces would maintain a long-term presence in the region through multinational exercises and training missions. In an effort to improve its capability and contributions to U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), the Navy agreed to the establishment of NAVCENT as a permanent billet headquartered in Bahrain, led by a three star admiral. In 1995, the Navy stood up Fifth Fleet as CENTCOM’s dedicated naval combat force. Improvements in communications, weapons, and targeting devices, as well as significantly upgrading its mine-hunting ships and aircraft, was also a reflection of the Gulf War.

At the strategic level, Desert Storm coupled with the breakup of the Soviet Union inspired the Navy to strengthen its evolution from Cold War operations to both blue water and littoral roles in regional conflicts. The Navy’s 1992 white paper From the Sea documented the new strategic approach, and it was refined two years later with Forward . . . From the Sea. Although the documents were controversial at the time, both became guides and sources for constructive discussion that shaped Navy policy throughout the 1990s.

Today in Naval History—First Shots Fired, 1861

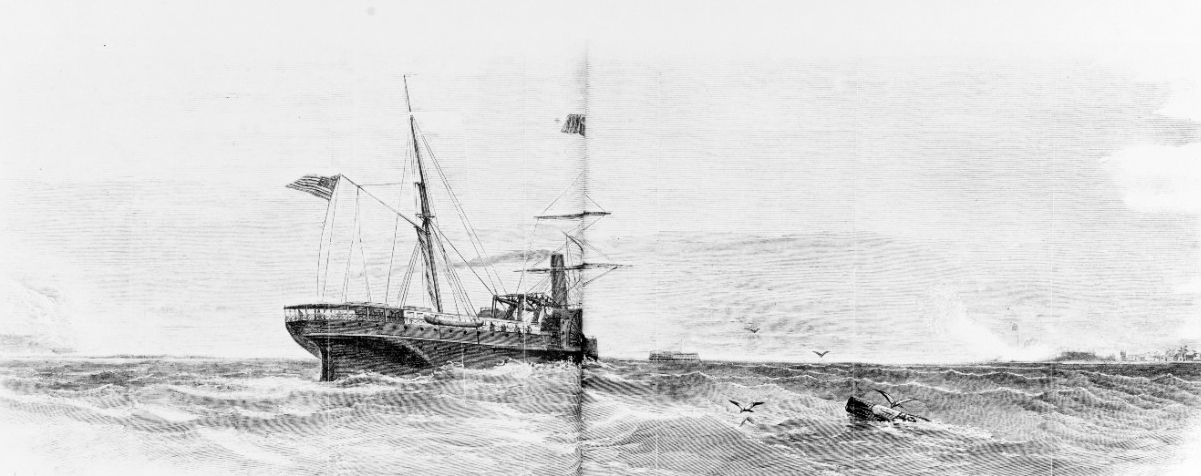

On Jan. 9, 1861, commercial steamer Star of the West was fired upon as it tried to deliver supplies to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The incident was the first time shots were fired in the lead up to the Civil War, although it did not trigger war at the time. When South Carolinians seceded from the Union on Dec. 20, 1860, they demanded the immediate withdrawal of the federal garrison at Fort Sumter. President James Buchanan refused to comply but was also careful not to make any provocative moves. Inside the fort, Union Army Maj. Robert Anderson and his 80 Soldiers subsequently requested supplies to continue operations. The Buchanan administration deliberately decided to dispatch a civilian ship, Star of the West, instead of a military transport, to keep tensions from flaring.

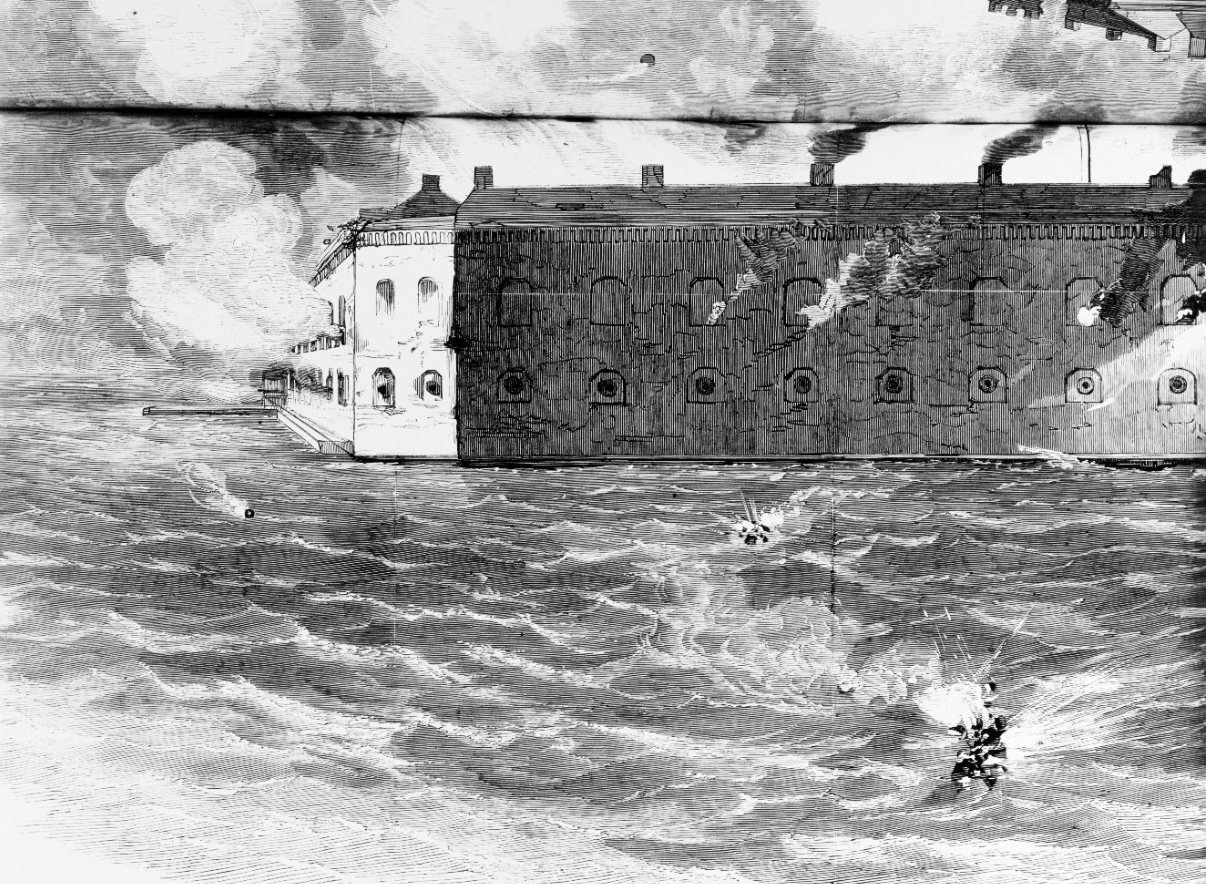

On Jan. 5, the unarmed steamer set course from New York to the South Carolina coast. While the ship was underway, Secretary of War Joseph Holt received a dispatch from the Fort Sumter commander stating that the garrison was now safe and supplies were not immediately needed. Anderson added that the Confederates were building gun emplacements overlooking the main shipping channel into Charleston Harbor. After receiving the dispatch, Secretary of War Holt realized that Star of the West was in grave danger and war could possibly erupt by completing the supply mission. He tried in vain to recall the ship, and Anderson was not aware that it continued to make its way toward his location. On the morning of Jan. 9, John McGowan, captain of Star of the West, steered the ship into the Charleston Harbor channel. Immediately, two cannon shots roared from a South Carolina battery on Morris Island, fired by Gunner George E. Haynsworth, who was a cadet at The Citadel in Charleston at the time. More shots were fired, but the ship suffered only minor damages. Anderson watched the engagement from Fort Sumter but did not respond in support of the ship. If he had, the Civil War might have started on that day. After Star of the West was fired upon, it turned back toward Union waters. The incident resulted in spirited talks on both sides. The standoff at Fort Sumter continued until Anderson’s troops were literally starved into submission. On April 12, Confederate batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter, marking the opening salvo of the Civil War. The next afternoon, Anderson agreed to surrender and evacuated the fort at noon on April 14. When his troops marched out of the fort, they waved the U.S. flag and prepared to carry out a 100-gun salute. On the 50th round, an explosion occurred, causing the only death of the Fort Sumter ordeal. Pvt. Daniel Hough of the U.S. 1st Artillery regiment was the first of as many as 850,000 Americans who would perish during the Civil War.

The loss of Fort Sumter was an important learning point for both the North and South in that the naval aspect of the Civil War was as important to the war’s outcome as any of the ground campaigns. Despite ongoing advances in transportation technology, the majority of troops and materiel moved by water. Those who controlled America’s waterways would probably win the war. Naval operations were directed by two leaders—Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and the Confederate States of America’s Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory. Both faced near-impossible tasks. Welles had to transform a peacetime fleet of 50 decrepit ships into a fighting force capable of patrolling and controlling thousands of miles of coastline and rivers. Mallory did not even have a navy, yet he had to stave off the U.S. fleet, all the while maintaining a steady flow of supplies from Europe to supply the Confederate army.

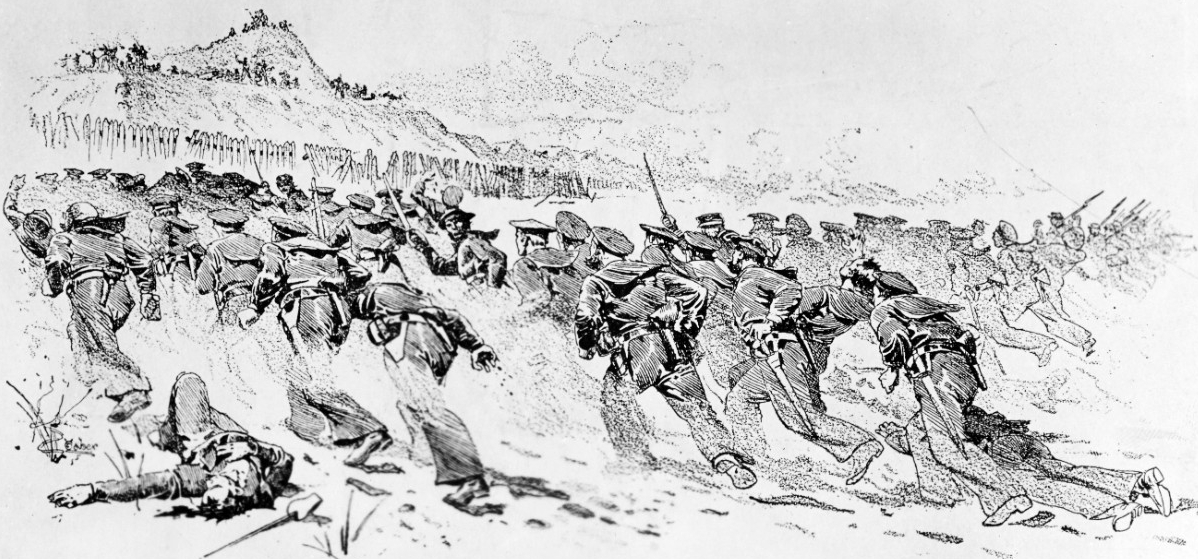

There were three essential aspects to naval warfare during the Civil War: the northern blockade of southern ports, the riverine operations, and attacks by Confederate commerce raiders on Union merchant shipping. In regard to the northern blockade, the vast majority of America’s manufacturing capacity was located in the northern states. There were a few industrial centers in the South, but not nearly enough to sustain a Confederate army. The Confederacy desperately needed European factories to produce for them. In 1861, President Abraham Lincoln was determined to prevent European access, and he proclaimed the southern ports were to be in a state of blockade. During the entire course of the war, a daily chess match occurred between the blockaders and blockade runners. The slow grind of the blockade was interrupted by large, dramatic battles as the U.S. Navy moved to permanently shut down key southern ports. On the riverine front, nearly all of the major urban areas in the south—with the notable exception of Atlanta—were located on a major river. Lincoln knew that in order to subdue the Confederacy, the Union had to gain control of interior waterways. Throughout the war, violent encounters occurred between U.S. Navy and Army gunboats and Confederate fortifications. Confederate cruiser attacks on Union merchant ships also played a significant role. Though small in number, the Confederate ships did a disproportionate amount of damage. Part of this was in form of propaganda, wearing down northern support for the war. One influential northern bloc of wealthy entrepreneurs, whose ships and goods were being destroyed by Confederate ships, saw the war as detrimental to business.

The Civil War also had a negative impact on the economies of other countries. Textile manufacturing areas in Britain and France that depended on southern cotton entered periods of high unemployment, while French producers of wine, brandy, and silk also suffered when their markets in the Confederacy were cut off. Confederate leaders were confident that southern economic power would compel European powers to intervene in the Civil War on behalf of the Confederacy, but Britain and France remained neutral despite their economic problems, and later in the war invested in new sources of cotton from Egypt and India. Although British Prime Minister Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, was personally sympathetic to the Confederacy, and many other elite Britons felt similarly, strong domestic abolitionist sentiment in Britain and in his cabinet prevented Lord Palmerston from taking stronger steps toward assisting the Confederacy. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte of France was also sympathetic to the Confederacy, but he wanted to pursue a joint policy with Britain regarding the American Civil War and so remained neutral. Moreover, Napoleon’s chief concern during the Civil War years was France’s intervention in Mexico. As the war progressed and more territory came under Union control, naval operations became more effective for the North and less of an international issue. However, until the successful capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina, in early 1865, the Confederate army was still able to obtain some supplies from abroad and through America’s waterways.