The Forgotten Bases of Ireland

Amidst the sheer carnage and devastation of World War I, the United States proclaimed and maintained a stance of neutrality for nearly three years. Woefully unprepared militarily, the United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917 in response to the Zimmermann note and Germany’s campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare (USW).[1] Although the USW policy was successful in depleting British supplies, with U-boats sinking more than 500,000 tons a month from February to June 1917, it also severely weakened Germany diplomatically and contributed to America joining the war, as U-boats frequently hit passenger ships killing innocent civilians, including hundreds of Americans.[2]

Much of this damage occurred in and around the Irish Sea, which was known as “U-boat Alley” due to the number of U-boats targeting ships going between Great Britain and the Atlantic Ocean.[3] The amount of tonnage sunk was staggering, with British officials reporting to the American ambassador that grain would run out within weeks. Although the United States did not immediately declare war, the Navy secretly began preparing for the inevitable in March 1917 by discussing cooperating with the Royal Navy. American officials knew that if the United States entered the war, not only would they need to secure the waters to send millions of troops and supplies to the front, they would also need to protect the seas to ensure Britain and other Allies continued fighting.

At the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, Admiral William Sowden Sims set sail to London on 31 March to secure information on what the Royal Navy was doing to combat U-boats and their plans for including the U.S. Navy in this fight. Admiral Sims was shocked to learn of the severity of the U-boat crisis, including warnings that Germany could defeat Britain by November, and cabled Washington to urgently send all available destroyers to Queenstown, Ireland.[4]

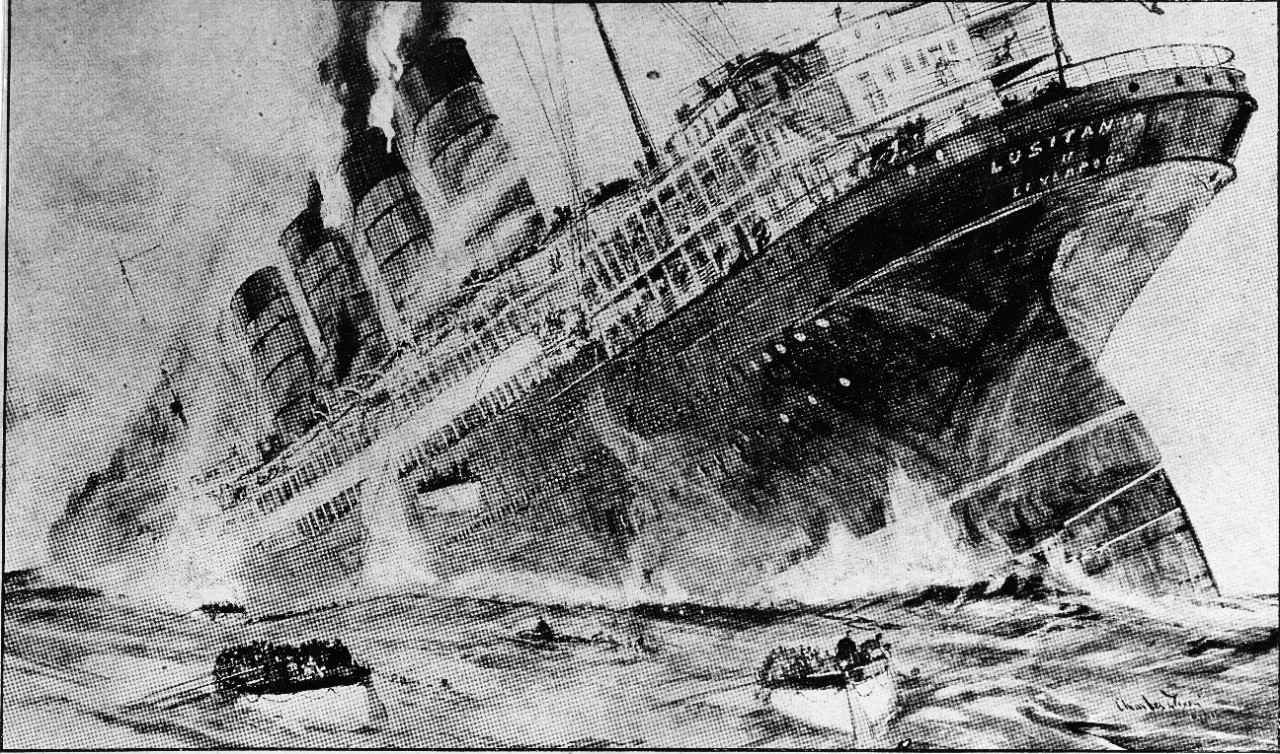

Sinking of the RMS Lusitania off of the Irish Coast: An illustration by Charles Dixon published in the 16 November 1918 issue of the London Graphic depicting survivors abandoning the sinking RMS Lusitania shortly after it was torpedoed on 7 May 1915 by a U-boat. A total of 1,198 civilians were killed, including 128 Americans. (NHHC, NH 892)

Located on the southern coast of Ireland in Cork Harbor, Queenstown, now known as Cobh, was the headquarters of the British admiralty in Ireland under the command of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly. For centuries, Queenstown was an assembly point for merchant ships. The heavy traffic made it an important port for the Royal Navy as it attempted to protect merchant ships from pirates and enemy warships. This became even more paramount during Germany’s USW campaign.

By 1917, the Queenstown base was the primary naval base in Ireland for defending against submarines lurking in the waters off the British Isles and clearing the minefields in the Irish Sea. For these reasons, the Royal Navy deemed American support at Queenstown essential to defeating Germany. The United States responded on 24 April 1917 by sending six destroyers under the command of Commander Joseph K. Taussig. The fleet included Conyngham (Destroyer No. 58), Davis (Destroyer No. 65), McDougal (Destroyer No. 54), Porter (Destroyer No. 59), Wadsworth (Destroyer No. 60), and Wainwright (Destroyer No. 62). This division would be the first American naval unit sent into European waters. Eventually, they were joined in Queenstown by nearly 7,000 Navy personnel and 86 additional vessels, including 41 destroyers, 30 sub-chasers, 7 submarines, 3 tugs, 2 destroyer tenders, 1 submarine tender, 1 “mystery ship,” and 1 minelayer.[5]

On 3 May, the destroyers were greeted with the signal “Welcome to the American colors” by the British destroyer HMS Mary Rose.[6] The American sailors were also welcomed by residents, with the town cathedral playing a rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Within four days, Navy sailors conducted their first mission. During each patrol, destroyer crews set sail for five to six days under the strict instructions of destroying submarines, escorting and protecting merchant ships, and saving the crews and passengers of torpedoed ships, with their primary goal being to destroy submarines.

There were many debates between the U.S. Navy and the Royal Navy regarding the best method for defeating U-boats. Although the United States and some in the Royal Navy argued for the convoy system, senior Royal Navy officials rejected the idea, stating that there were not enough vessels to escort all merchant ships and that the convoys would create valuable targets. However, after losing millions of tons of shipping, thousands of lives, and hundreds of ships, the officials opposing convoys were outnumbered, and, on 21 May 1917, the British admiralty voted to adopt the convoy system.

With the Allies shifting tactics to the convoy system, the Navy sent more destroyers to support escort missions. By the end of the war, 43 percent of the 1,577 escort duties completed by American forces were conducted by the sailors stationed at Queenstown, the most of any base.[7]

The base at Queenstown was important for numerous reasons. First, of the 80 destroyers deployed during the war, 47 of them were based there. Second, it was the first time the Navy fell under the command of a foreign military. Lastly, it was the first U.S. base in Europe and served as a preview of what was to come.

Naval Air Station at Queenstown

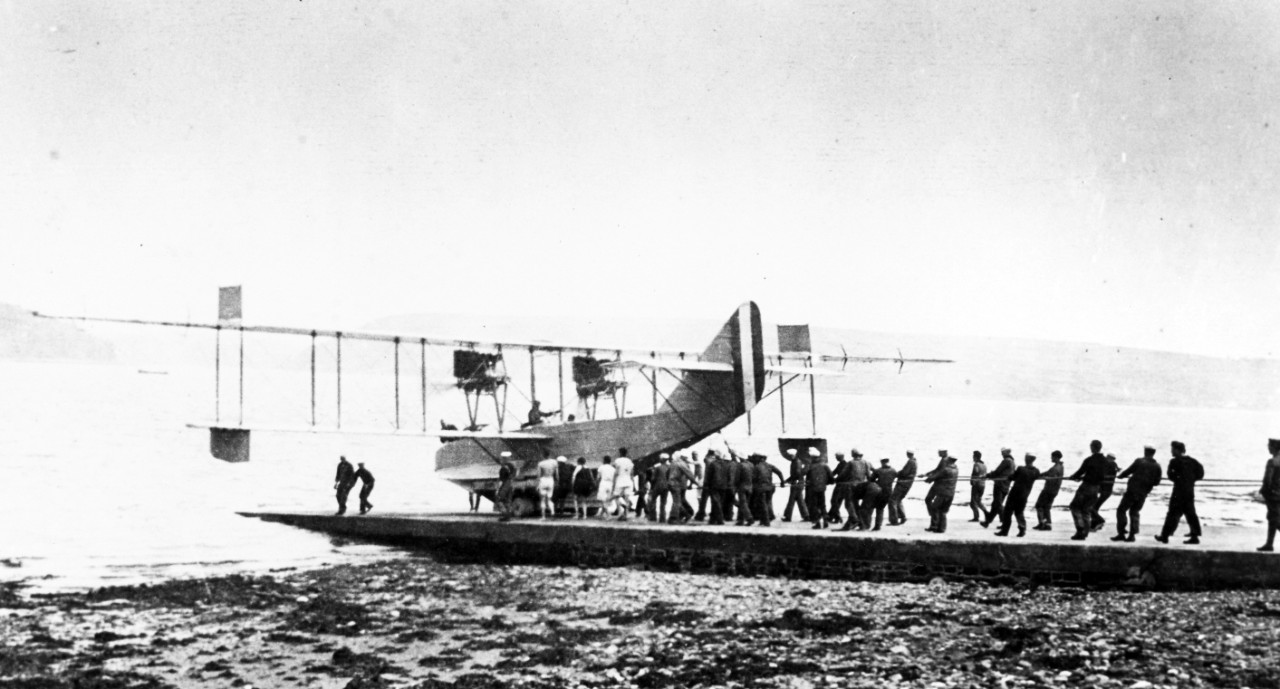

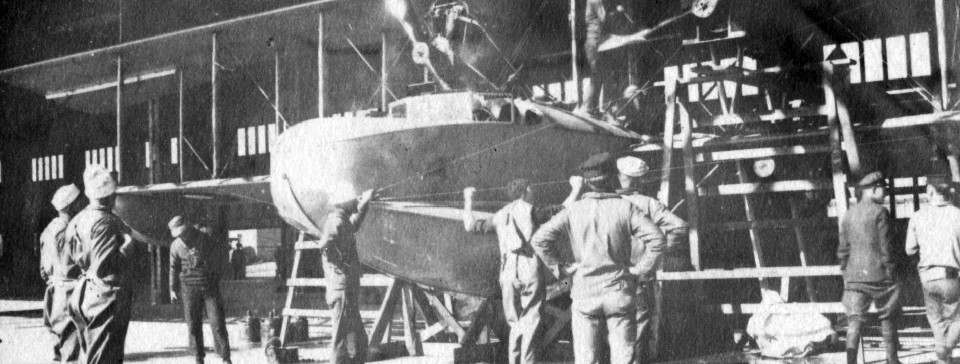

In addition to the operating base in Queenstown, the Navy created an air station to serve as a supply base, training ground, and patrol station. Located on the southeastern side of Cork Harbor, close to Aghada, the station was strategically placed where U-boats were most active, which meant it was an ideal location for identifying and targeting submarines. The base also functioned as the main supply base for naval air stations in Ireland and the training facility for all Curtiss H-16 pilots serving at these bases.

Initial plans called for a base to accommodate 24 seaplanes, 75 officers, and 2,300 men, with the goal of the base being the largest naval air station in Ireland. Construction began in December 1917, and by 22 February, the Navy officially commissioned the base under the command of Lieutenant Commander Paul Peyton.[8] The first shipment of 8 aircraft arrived in June, with a second shipment of 10 aircraft arriving in July.[9] Each plane had to be rebuilt, modified, and tested before being commissioned for the Queenstown base or shipped to the other stations in Ireland.

The personnel at the station were also tasked with training new pilots to operate the Curtiss H-16 flying boats. Training pilots completed 25 test flights in August, 34 in September, 50 in October, and 25 flights in November.[10] With much of the focus on training pilots and preparing them for deployment, efforts to complete the base were delayed. The station did not become fully functional until 30 September 1918, making it the last station to become operational in Ireland.

The delays in finalizing the station and the focus on training contributed to its limited war record. In total, over nearly 40 days, the aircrew completed 64 patrol flights spanning 198 hours and 11,568 miles.[11] Queenstown pilots were credited with three bombing attacks against German submarines.[12] Although the number of patrols was limited, the base served a critical role in the overall war effort by ensuring aircraft and pilots were ready for deployment and had the necessary skills to attack submarines and protect Allied ships.

By the end of the war, the Queenstown base had 28 Curtiss H-16s, 72 officers, and 1,426 men.[13] The Navy officially closed the base in April 1919. Today, besides the pillars that once stood at the entrance of the air station, few elements of the base remain.[14] Most of the facilities at the station were deconstructed and either shipped back to America or sold at local auctions. Many of the facilities not deconstructed immediately following the war were destroyed during the Irish Civil War (1922–23).

Located at the southern entrance to the Irish Sea, U.S. Naval Air Station Wexford was commissioned on 2 May 1918. Possibly the most strategically located base, the Wexford station was established within 12 miles of the Tuskar Rock and its lighthouse, an area of the Irish Sea known as the “Graveyard of Ships.”[15] The Navy designed the base to patrol a radius of 100 miles covering the Irish Sea, the western coast of Wales, the Bristol Channel, the south of Queenstown, and the waters near Dublin, thus enabling the Navy to patrol and monitor all ships in and out of the south Irish Sea.[16]

Construction of the base began in December 1917, with plans to accommodate 46 pilots, 394 men, and 18 Curtiss H-16s. The work was strenuous. Navy personnel had to build the station from the ground up. They faced incessant rain, inadequate clothing, and worker shortages due to Irish laborers engaging in political strikes.[17] After nearly five months of construction, the base was officially commissioned on 2 May under the command of Lieutenant Commander Victor D. Herbster.

On 18 September, the naval station in Wexford became fully operational after receiving four Curtiss H-16s from Queenstown. Unfortunately, shortly after the arrival of the H-16s, two were damaged, leaving the aviators with only two functioning aircraft. Nevertheless, within three days of receiving the seaplanes, naval aviators dropped two bombs and attacked their first submarine. In mid-October, pilots attacked three additional U-boats. Two of the bombings resulted in oil patches appearing on the surface.[18]

The Wexford naval air station was fully operational for only 54 days, yet by the end of the war, the base housed five Curtiss H-16s, completed 98 flights, and covered 19,135 miles over approximately 312 hours of flying time.[19] The achievements of the Wexford station must not be overlooked. Even though two Curtiss H-16s arrived in mid-October and another in early November, for most of the first month, pilots only had two seaplanes, meaning they completed most of the 98 flights with only two aircraft. Equally impressive is the fact that crews flew 19,135 miles in less than 54 days of operation, as multiple days were deemed unsafe to fly due to the weather.

The base that once accommodated 22 officers and 405 men officially closed in February 1919. Today, the only evidence that the base ever existed is the unused slipway and a historical marker installed by the Wexford County Council in 2018 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the U.S. Navy.[20]

Naval Air Station at Whiddy Island

Situated on the eastern side of Whiddy Island near the head of Bantry Bay, the naval air station at Whiddy Island was operational from 25 September 1918 until January 1919. Historically, the island’s location on southwestern Ireland made it an important maritime fortification, used to guard and fend off any potential invaders trying to reach England via the Irish Sea.[21] With this in mind, the Navy determined that the base would serve a critical role in combating U-boats by monitoring the southwest coast and guiding convoys as they approached and entered the Irish Sea.[22]

Although the location was critical strategically, the land was underdeveloped, and the Navy had to build from the ground up. With plans for 24 Curtiss H-16s, 58 officers, and 489 men, the Navy needed roads, a water system, slipways, barracks, and hangars.[23] Development was slow, and in early March, when the first detachment of American sailors arrived, the base still did not have any accommodations. Therefore, the Navy had to temporarily house sailors in the town of Bantry Bay. The time commuting to and from the base, as well as the worker shortages, poor weather conditions, and lack of supplies, contributed to significant delays. Personnel ultimately manage to complete the barracks and establish clean drinking water in April 1918.

On 4 July, the Navy commissioned Naval Air Station Whiddy Island. Even though the base was completed in July, it did not become operational until 25 September after receiving two seaplanes.[24] During its 46 days of operation, naval airmen completed 25 patrol missions, spanning 65.5 hours and covering 3,870 miles.[25] Overall information regarding the patrol missions is limited; however, the airmen at Whiddy Island are credited for guiding five convoys and rescuing and rendering aid to a plane stationed at Queenstown.[26]

Following the armistice on 11 November 1918, the station ceased operations, and personnel began demobilizing the base, with all equipment auctioned off or removed by January 1919. Although much of the station was deconstructed, the memory and sacrifice of the aviators who served at Whiddy Island lives on, with the town of Bantry Bay holding ceremonies that commemorate the U.S. Navy aviators and honor the loss of Petty Officer Walford August Anderson, a radio operator who tragically died during a plane crash.[27]

Naval Air Station at Lough Foyle

Although the majority of the Navy’s efforts in Ireland were focused on the southern coast, the Navy also installed one air base on the north coast in Lough Foyle. Located between County Donegal and County Londonderry, the station allowed the Navy to patrol over the North Channel entrance into the Irish Sea. The combination of bases in southern Ireland and the base at Lough Foyle enabled the Navy to monitor all entry points of the Irish Sea, without which a U-boat could enter the waters between Ireland and Britain and target vessels near Belfast, Dublin, and Liverpool. As such, the base was vital to the Navy’s mission against Germany.

Under the supervision of the Royal Navy, local Irish laborers began construction on 5 January 1918 with design plans to house 18 Curtiss H-16s and to accommodate 46 officers and 394 men.[28] As with the air stations in southern Ireland, political unrest resulted in temporary strikes by local Irish workers, thus delaying the development of the base. Although the location was strategically valuable, it also presented numerous challenges, including shipment delays due to the Queenstown supply base being nearly 300 miles away.[29] Amid the challenges, on 1 July, the United States formally commissioned the base under the command of Commander Henry Cooke. The first shipment of aircraft arrived a few weeks later, and by 21 August, Navy pilots completed the first practice mission.

The Lough Foyle station was the first U.S. naval air station in Ireland to receive Curtiss H-16s ready for action, and it became fully operational on 3 September 1918. In its two months of operation, the base never reached its original expectations. Terrible weather conditions resulted in pilots conducting significantly fewer patrols than the bases at Queenstown and Wexford. Even though there were seven seaplanes at Lough Foyle Station, the pilots only completed 41 flights spanning 6,000 miles over 99 hours.[30]

Although the base did not reach its full capacity, it was still critical for patrolling the north entrance to the Irish Sea, and the pilots at the base were credited with damaging at least one submarine. On 19 October, while patrolling a convoy of 32 ships, Ensign George S. Montgomery spotted a U-boat stalking the convoy and dropped two bombs on the submarine.[31]

All flights ceased once the armistice of 11 November went into effect. The 10 pilots, 10 ground officers, and 432 men began to close the station. By 22 February 1919, the Lough Foyle naval air station was decommissioned. The Navy would return to the Lough Foyle region during World War II when the United States opened a naval base in Londonderry, yet little remains of the Navy’s base from World War I.

Naval Air Station at Berehaven

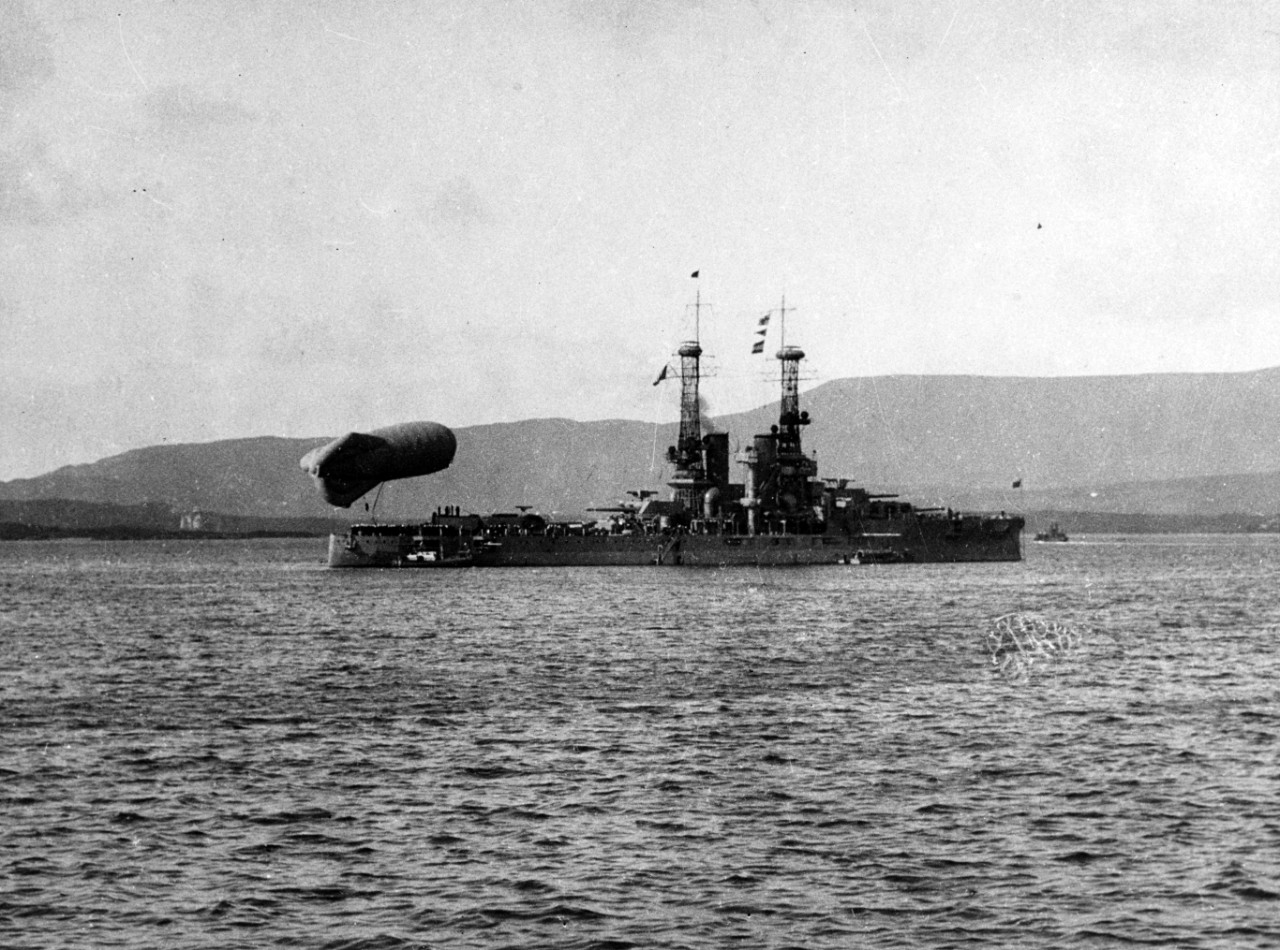

In addition to the four naval air stations, the United States also commissioned a kite balloon station located near Berehaven Harbor in the southwest of Ireland. The kite station, once called the “most logical port in Europe,” was the only American kite balloon station in Ireland.[32] The location was ideal as the harbor was deep enough to dock the destroyers that would fly the kites, and its proximity to the main transatlantic route allowed the Navy to locate submarines that may be tracking ships sailing to and from England.

The United States agreed to acquire the land from the Royal Navy on 26 April 1918 and commissioned it three days later. In its early days, flight officers practiced flying the balloons using tow trucks as there were no destroyers based at Berehaven, with the nearest destroyers in Queenstown over 75 miles away. By mid-June, the Navy had 30 kite balloons in Berehaven, yet the base did not have a single destroyer. Thus, the base was essentially useless. This factored into the Navy’s decision to send 7 pilots and nearly 40 enlisted men to the kite balloon station at Brest, France. The base’s future seemed in doubt, yet on 14 July, the HMS Flying Fox, a 24-class sloop, anchored nearby in Bantry Bay. The pilots stationed at Berehaven used this opportunity to practice patrolling the waters.

The Berehaven station continued facing questions over its future as many argued it was too far from Queenstown, yet these concerns were squashed in mid-August when 9 officers and 72 men from Brest were sent to Berehaven. Shortly thereafter, on 23 August, three U.S. battleships—Nevada (Battleship No. 36), Oklahoma (Battleship No. 37), and Utah (Battleship No. 31)—arrived. Overall, the officers at Berehaven completed very few missions. By the time the warships arrived and were properly equipped with balloons, it was early October, and within a month, the Allies and Central powers signed the armistice.

At the end of the war, the United States had 16 balloons, 12 officers, and 91 men at Berehaven.[33] On 14 February 1919, the Navy returned the base to the British government. Following Irish independence, the British retained the Berehaven base under the Treaty Port until 1938.[34] Today, the former naval air station acts as a golf club, with little evidence of its previous life.[35]

Effectiveness of Naval Operations in Ireland

By the fall of 1918, it was clear that Germany’s USW campaign was unsuccessful in bringing Britain to its knees and that its military leaders had miscalculated the impact American forces would have on the war. Although historians continue to debate the extent of America’s role on the outcome of the war, the reality is that, in under two years, the United States sent over a million service members to Europe who assisted in stopping German advances and provided much needed reinforcements, none of which, would have been possible without the Navy’s support in addressing Germany’s USW.

When America entered the war, the U-boat campaign was devastating the British shipping lines, with concerns growing over the potential impact on food and military supplies. Following the declaration of war, the Navy immediately sent destroyers to Ireland to neutralize this threat. The United States also established air stations to help patrol the waters and identify any U-boats stalking Allied shipping. The combination of the convoy system, additional naval vessels, and air power significantly decreased the effectiveness of USW, with the men serving in Ireland playing a pivotal role in this effort.

Once in Ireland, the Navy faced numerous challenges in establishing a presence. Besides the operating base in Queenstown, the other bases had to be built from the ground up, with personnel building roads, water systems, barracks, hangars, and slipways. The limited infrastructure severely hampered development and delayed air operations. This issue was further exacerbated by the political unrest and the workers’ strikes organized by Irish nationalists in response to potential conscription by the British government. Finally, weather conditions frequently delayed air and sea patrols, resulting in personnel completing fewer missions than initially expected.

Despite facing these challenges, Navy personnel in Ireland completed 360 convoys and 315 single ship escorts and patrolled roughly 40,600 miles over 228 flights, with all air patrol missions being completed in under two months. Through the combination of sea and air defense, Germany’s USW campaign began to lose momentum, and Allied tonnage lost decreased from 687,507 in June 1917 to 351,748 in September 1917.[36] These numbers continued to decrease, and, once air support was introduced in September 1918, tonnage lost dropped to under 200,000.[37]

Conclusion

During the four years of war, Germany sank 5,708 ships carrying over 11 million tons, including 6.5 million tons of British goods. The British government warned the United States that without additional naval support, Germany would win. The Navy met the challenge and brought much-needed relief by deploying a large force to Ireland to protect shipping from U-boats. The focus on trench warfare and Ireland’s fight for independence and subsequent civil war has often overshadowed the American naval presence in Ireland. Yet, the accomplishments achieved by American sailors and naval aviators should not be overlooked as they assisted in defeating Germany’s USW, keeping Great Britain in the war, and demonstrating to the German armed forces that surrender was the only option.

--by Jacqueline S. Evans, NHHC writer-editor

Further Reading:

Conrad, Dr. Dennis, and S. Matthew Cheser, “The Return of the Mayflower: Arrival of Destroyers at Queenstown,” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), May 2017.

Havern, Christopher B., Sr., Ensuring the Lifeline to Victory: Antisubmarine Warfare, Convoys, and Allied Cooperation in European Waters during World War I. Washington, DC: NHHC, 2020.

Havern, Christopher B., Sr., “Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and Freedom of the Seas,” NHHC, October, 2020.

***

[1] The Zimmermann note was a coded telegram written by the German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann, to the Mexican government proposing a military alliance that would see Germany helping Mexico regain Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

[2] David C. Gompert, Hans Binnendijk, and Bonny Lin, “Germany’s Decision to Conduct Unrestricted U-boat Warfare, 1916.” In Blinders, Blunders, and Wars: What America and China Can Learn (California: RAND Corporation, 2014), 63–70. In February 1917, Germany sank 540,006 tons. This continued to increase with 593,841 in March, 881,027 in April, 596,629 in May, and 687,507 tons in June.

[3] Liam Nolan and John E. Nolan, Secret Victory: Ireland and the War at Sea 1914– 1918 (Cork, Ireland: Mercier Press, 2009), 168.

[4] William Sowden Sims, The Victory at Sea (New York: Doubleday, Page, and Company, 1921), 11.

[5] Walter S. Delany, “Bayly’s Navy,” NHHC, 23 August 2017.

[6] Dr. Dennis Conrad and S. Matthew Cheser, “The Return of the Mayflower: Arrival of Destroyers at Queenstown,” NHHC, May 2017.

[7] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies (Washington DC: Office of Naval Intelligence,1919) 29. During the war, there were three bases tasked with escort duties, including the naval bases in Brest, Gibraltar, and Queenstown. The forces at Brest completed 350 convoy escorts and zero single ship escorts, while the forces at Gibraltar completed 453 convoy escorts and 99 single ship escorts.

[8] Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick, United States Naval Aviation 1910–2010 (Washington, DC: NHHC, 2015), 32.

[9] Geoffrey L. Rossano, Stalking the U-boat: U.S. Naval Aviation in Europe during World War I (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010), 218.

[10] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 218.

[11] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 49.

[12] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 219.

[13] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 49.

[14] Darie Brunicardi, “The US Navy at Queenstown,” History Ireland 25, no. 3 (May–Jun. 2017): 38–40.

[15] Liam Gaul, Wings Over Wexford: The USN Air Station Wexford 1918–19 (United Kingdom: History Press, 2017), 46.

[16] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 219.

[17] Liam Gaul, Wings Over Wexford, 35.

[18] “Lieutenant Commander Walter A. Edwards, Aviation Section, Staff of Vice Admiral William S. Sims, Commander, United States Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, to Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels,” 25 October 1918, NHHC, accessed 18 March 2024.

[19] Liam Gaul, Wings Over Wexford, 46.

[20] Samuel Cox, “Wexford Ireland’s Ties to U.S. Naval History,” NHHC, 18 July 2018.

[21] Wes Forsythe, “Bantry Bay, County Cork, a Fortified Maritime Landscape,” Historical Archaeology 41, no. 3 (2007): 51–62.

[22] Evans and Grossnick, United States Naval Aviation 1910–2010, 46.

[23] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 47.

[24] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 223.

[25] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 49.

[26] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 223.

[27] “Whiddy Island Commemorates American,” West Cork Islands, Jun. 25, 2014.

[28] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 47.

[29] Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons, Michael D. Roberts, vol. 2, The History of VP, VPB, VP(HL) and VP(AM) Squadrons (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 2000), 761.

[30] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 49.

[31] Edwards to Daniels, 25 October 1918, NHHC.

[32] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 227.

[33] Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies, 49.

[34] During the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations (1921), the representatives of the Free State of Ireland agreed to allow the Royal Navy to operate three ports in Ireland. The British government requested access to these ports due to concerns that there still could be U-boats in the Irish Sea.

[35] Rossano, Stalking the U-boat, 230.

[36] Gompert, Binnendijk, and Lin. “Germany’s Decision to Conduct Unrestricted U-boat Warfare, 1916,” 67.

[37] Gompert, Binnendijk, and Lin. “Germany’s Decision to Conduct Unrestricted U-boat Warfare, 1916,” 67.