Ask any aviator to pick one assignment that is the high point of his career, and all fortunate enough to have commanded an aircraft carrier will point to that moment. After all few have the satisfaction of leading a floating city, let alone one with the power to rain destruction down upon an enemy target. Among carrier skippers there have always been particular ships that are considered “plum assignments,” perhaps none more than Enterprise, the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, as she took shape at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company in Virginia for her commissioning on November 25, 1961.

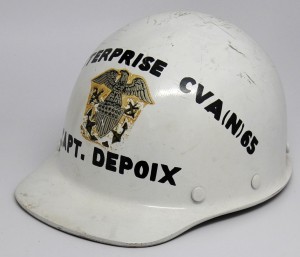

The man selected as her first skipper was Captain Vincent de Poix, who certainly understood the legacy of his seagoing command’s name. In 1942, then a young lieutenant, he flew from the deck of the first carrier Enterprise (CV 6) operating in the waters off Guadalcanal, splashing an enemy plane in air-to-air combat and participating in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. His service in command of the new Enterprise placed him in charge of scores of young people manning a ship unlike any before in the midst of the Cold War. In the months leading up to her commissioning, de Poix spent many an hour walking the passageways and inspecting more than 3,500 compartments on board. During these travels he wore a white hard hat adorned with the Navy officer crest, his name, and that of the ship, this artifact representing a time when the flattop that is now decommissioned represented the dawning of a new era in naval aviation. He wore his flight jacket, a symbol of naval aviation, on her maiden deployment and during her time at sea operating in the Caribbean during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

“We have inherited probably the most illustrious name in the history of our country’s navy, that of Enterprise,” de Poix said in his speech delivered that November commissioning day fifty-three years ago today. “This name carries with it glory and prestige…It also carries with it responsibility to keep the name untarnished. It must be our intention to do this and more…to add to its luster.” He and other “Big E” plankowners, and all that followed, did just that.

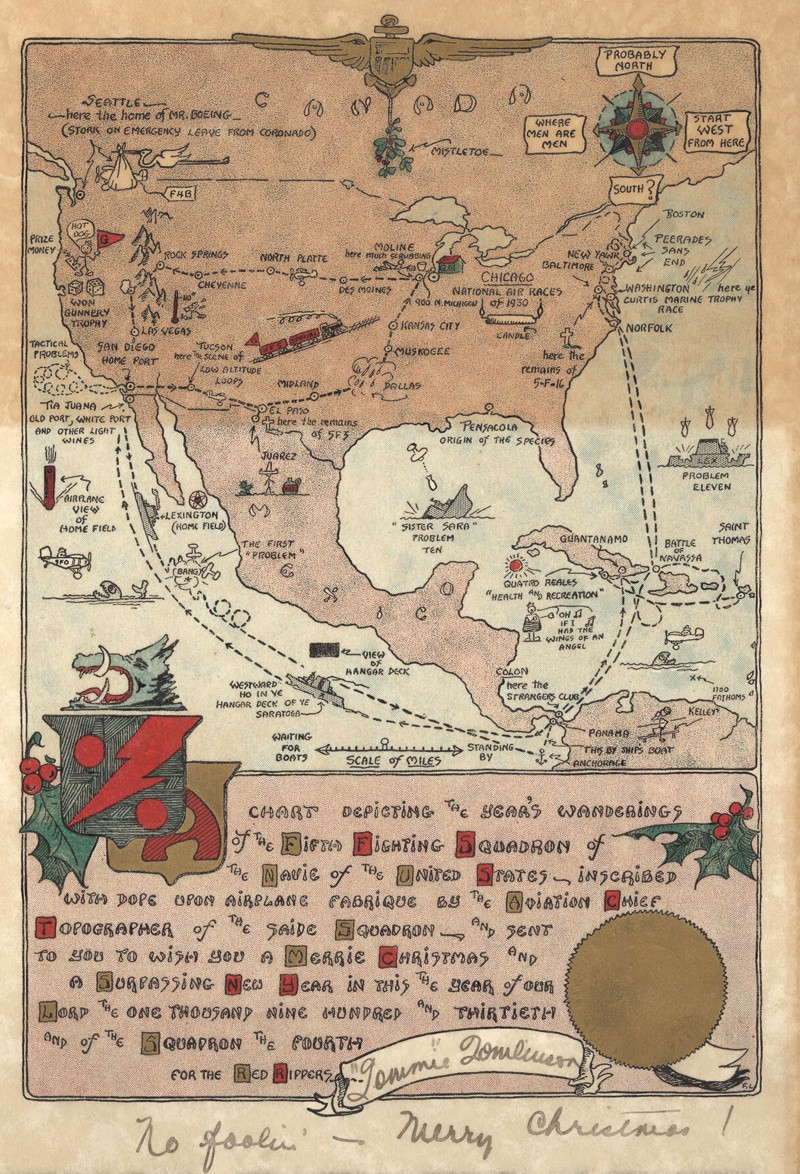

The collection of the museum’s Emil Buehler Naval Aviation Library includes a number of items relating to the holiday season, notably menus from shipboard dinners and Christmas cards sent out by squadrons. The most interesting example from the latter in its originality, color, and detail is the card sent out by the members of the Fighting Squadron (VF) 5B, the famed “Red Rippers,” in 1930. Using doped fabric as its canvas, the card consists of a chart documenting the travels of the squadron during the year, the cartoons and verbiage on it highlighting notable events. To this end, a stork carries an airplane to mark delivery of new F4B fighters to the squadron and bombs rain down on a silhouette of the carrier Lexington (CV-2) in representation of Fighting Five’s participation in Fleet Problem Eleven. The drawing above the caption “airplane view of home field” captures the postage stamp like appearance of a carrier deck from altitude, while graves mark the location of mishaps in which airplanes were damaged beyond repair. Appropriately, given the yuletide season, mistletoe hangs from naval aviator wings at the top of the card. The card is a fitting memento of aviation’s colorful Golden Age and one of the most historic squadrons in all of naval aviation history.

The roll call of nicknames adopted by squadrons over the course of naval aviation history includes those like the Sundowners, Red Rippers, Fists of the Fleet, and Tophatters, each name harkening back to the very origins of the squadrons themselves. During the incredible expansion of naval aviation that occurred during World War II, scores of new squadrons were established, some of them surviving into the postwar era and others passing into history when hostilities ended in 1945. Recently, through the generosity of the son of a former skipper, an interesting memento from one of the most acclaimed carrier squadrons of World War II was placed on loan for display in the museum.

Robert A. Winston was a well known figure in naval aviation before the outbreak of World War II, his popular book Dive Bomber, which was published in 1939, recounting his experiences as an aviation cadet in the late 1930s. Placed on inactive duty in the Naval Reserve in 1939 following his active duty commitment, he joined the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation as a test pilot for export versions of the company’s F2A Buffalo, spending time overseas in Europe in the first year of World War II, during which time he met his future wife in Sweden and escaped France ahead of the advancing German Wehrmacht in 1940.

Returning to active duty in the Navy, the aviator who had been a newspaper reporter before entering the service in 1935, eventually was assigned to the Bureau of Aeronautics as a public information officer. Yet, he clamored to return to the cockpit, especially after the United States entered the war in December 1941. Eventually, he wrangled an assignment for refresher training in fighters, from which he proceeded to Naval Air Station (NAS) Atlantic City, New Jersey, to assume command of his own outfit, Fighting Squadron (VF) 31 equipped with the Navy’s newest fighter, the F6F Hellcat.

At 35 years of age, Winston was an old man literally and figuratively in a squadron that consisted primarily of ensigns fresh out of flight school. Among them competition was fierce as recounted in Fighting Squadron, another book by Winston that recounted his time in VF-31. “The one way I could keep them in line was by competition. They all loved to fly more than anything else in the world, and they all wanted to fly fighters.”

As the pilots began to meld into a cohesive fighting unit, they began thinking about a nickname, settling not on some fearsome animal or personage, but on a common kitchen utensil. To the drawing of a meataxe they added a pair of wings reflecting their air combat mission. As their motto, the “Meataxers” chose “Cut ’em down,” which would prove prophetic as the squadron finished the war with 165.5 kills and produced 14 aces.

Winston would lead the squadron on its first combat tour flying from the deck of the light carrier Cabot (CVL 28), which included action in the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot on the first day of the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Either made during his tour or presented to him upon his detachment was a meataxe on which was painted the squadron motto. On the other side is a taped list of pilots, including Lieutenants (junior grade) Cornelius Nooy, who finished the war with 19 kills, and Ray “Hawk” Hawkins, who splashed 14 Japanese aircraft.

Writing about his detachment, Winston recalled, “As I waved goodbye to the group at the gangway I was filled with mixed feelings of relief and regret, for with this departure I realized that my days as a squadron commander and as a fighter pilot were past.” That past lives on in memory and in the meataxe that will be displayed in proximity to the replica island of Cabot, one of the carriers from which VF-31 “Cut ’em down” during World War II.

On May 15, 2013, the National Naval Aviation Museum received historic artifacts that once belonged to Ensign William Devotie Billingsley, who on June 20, 1913, became the first naval aviator to die in the line of duty. Once part to his dress uniform, the pair of epaulettes and fore and aft hat were donated on behalf of the family by William Lee, who first came in contact with the Billingsleys when as a teenager he worked for a brother of William Devotie Billingsley at a grocery store in Winona, Mississippi. When he got older, Lee met another brother, who told him the story of their family’s tragic chapter in naval aviation history. That inspired a life-long dedication on Lee’s part to learn as much as possible about the fallen aviators and ensure that his story was not forgotten.

Hailing from Winona, William Devotie Billingsley ventured far away from home to attend the United States Naval Academy, graduating in the Class of 1909. An expert rifleman with a fondness for classic poetry, he made an impression on his classmates. “He has won his many friends by his constant good nature and ready sympathy,” one of them wrote in the Lucky Bag, the Naval Academy yearbook. “When it comes to nerve and determination, Bill is right there—he doesn’t know what the word ‘can’t’ means.”

It was these latter qualities that perhaps inspired him to seek duty in aviation, guiding the primitive wood and fabric seaplanes of the day into the air a supreme test of nerve for those young officers that counted themselves among the first sailors in the sky. In the fall of 1912, he reported to Greenbury Point across the Severn River from the Naval Academy, the site of one of the encampments that was home to the Navy’s small aviation establishment prior to the establishment of NAS Pensacola. Ensign Billingsley got his first taste of flying there as well as in the skies over Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where the fleet traditionally convened for winter maneuvers each year.

Friday, June 20, 1913, the complement of aviators, mechanics, and airplanes having returned to Greenbury Point from Cuba, was a typical day of flying in the Maryland skies. A pair of seaplanes, the A-2 and B-2, was scheduled to fly across the Chesapeake Bay to St. Michaels, Maryland, on what then passed for a cross-country flight. Billingsley was at the controls of the latter airplane, with Lieutenant John Towers, the senior aviator on site, replacing a mechanic on the flight at the last minute.

The flight proceeded normally until the seaplanes were a few miles from their destination, at which time a sudden gust of wind unexpectedly lifted the tail of the B-2 while it was at an altitude of about 1,600 feet. With the aircraft pitching forward in a 65 degree dive, Billingsley and Towers were both thrown forward, the young ensign losing his grip and hurtling through the air towards the water while Towers managed to grab part of the airplane and hold on until it hit the water. That Towers survived was miraculous.

The crash made headlines across the country for it marked the first fatality in U.S. naval aviation. Though Billingsley’s death cast a pall over the Navy, it inspired a technical development that affected aviation. Amazingly not all aircraft of the day were equipped with a restraining strap for the pilot and when aviation manufacturer Glenn Curtiss arrived in Annapolis to visit Towers, who was recuperating from his injuries, they discussed the need for such equipment, the result being a buckled seat belt that became standard on both civilian and military aircraft.

Lee recalled that about three years ago the Winona community started a drive to set up a Mississippi Archives and History marker for Billingsley in his hometown. The history marker was dedicated on October 24, 2011, with a ceremony that included a Navy flyover provided by Naval Air Station (NAS) Meridian, Mississippi and included as guests the Commanding Officer of NAS Meridian and Mississippi Army National Guard general officers with a keynote speech by U.S. Senator Roger Wicker.

Following the marker dedication, the ceremony concluded at Oakwood Cemetery where student pilots from NAS Meridian laid a wreath on the grave of Billingsley, the ornate headstone featuring a carving that depicts the epaulettes and a fore and aft hat donated the museum. (LTJG Lisa Lill contributed to this story)

An interesting bookend to the long service of Naval Air Station (NAS) Cubi Point in the Philippines recently arrived at the museum through the efforts of Captain Dan “Darth” Cain, USN (Ret.). Back in 1992, Cain commanded the Freelancers of Fighter Squadron (VF) 21, which was part of Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 5 embarked in the carrier Independence (CV 62). During the period March 17-21, 1992, Indy had the distinction of being the last U.S. Navy flattop to make a port call at Naval Base Subic Bay in the Philippines, the members of CVW-5 spending the liberty period at NAS Cubi Point. In the aftermath of the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in 1991 and the vote by the legislature of the Philippines to not extend the United States leases on the military installations in that nation, both Subic Bay and Cubi Point were slated to close later that year.

“We had the biggest blowout and festive time,” Cain recalled, “including…the catapult to the pool, 5K (sort of) run with wheelbarrows uphill from the O’Club to the BOQ and back with the squadron COs in them, and the “Tug A War” from hell where we had to defeat each squadron in the air wing and win numerous other events to decide who had the best squadron in the air wing.” With the NAS Cubi Point O’Club famous throughout the Navy for the colorful plaques that adorned it, the spoils of victory in the competition was a plaque that would be the last to hang in the bar until it was disassembled and shipped back to the United States for display at the National Naval Aviation Museum.

Soon VF-21 joined the rest of the air wing back aboard ship for the remainder of the WestPac cruise, leaving behind the plaque reading “Final Fling Last Cubi O’Club Air Wing Party March 19, 1992” and proclaiming the Freelancers as the top squadron. In subsequent years Captain Cain visited the museum on numerous occasions to donate items from his service with VF-21 and during Operation Iraqi Freedom. When he did not find the plaque in the Cubi Bar Café, he enlisted the aid of Museum Deputy Director Buddy Macon in searching the inventory of items received from NAS Cubi Point when it closed. The plaque earned in the spirited completion was not among them.

Fast forward two decades from the events at NAS Cubi Point to a place far removed from the blue waters and mountainous jungle of the Philippines. During a solo cross-country flight in November 2012, a flight student from NAS Meridian, Mississippi, made a refueling stop at the airport in Grand Junction, Colorado. While visiting West Star Aviation, a local FBO, he noticed the plaque hanging on a wall, one of the names listed that of his simulator instructor back at NAS Meridian, Captain Jody Richardson, USN (Ret.). Upon hearing the news, the simulator instructor and VF-21 veteran called his old skipper and told him he would not believe where the plaque was located.

For some reason, the plaque never made it into the club and instead remained in the workshop of Mr. Ben Martinez, who crafted many of the plaques for squadrons over the years. After NAS Cubi Point closed, Mr. Doug Thompson was part of a group that sought to develop a NAS Cubi-themed restaurant, their efforts going to the extent of visiting the site of the former base. Finding Martinez, they acquired all of the plaques that he had stored and returned with them to the United States. When the restaurant idea failed to materialize, Thompson decided to loan the plaques to his employer, West Star Aviation, and that was why the flight student happened upon it in Colorado. It was through his generosity and the efforts of Captain Cain and Rear Admiral Mark Vance, Commander of the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center at NAS Fallon, Nevada, that the plaque has finally found its way to its intended final location.

Thus, plaque from the Cubi Point O’Club’s “Final Fling” will finally hang alongside other memorabilia from the famous Pacific Fleet watering hole, a symbol of the passing of an era in naval aviation history.

For U.S. Navy sailors, whether on ocean waters in the days of John Paul Jones or in the cockpits of aircraft following the dawn of U.S. naval aviation in 1911, the ability to chart a course was among the most important of skills. While the modern era has given birth to global positioning systems that can pinpoint a location within moments, that was not always the case as evidenced by this artifact carried by a naval aviator on board the aircraft carrier Cowpens (CVL 25) during the final months of World War II. Standard equipment for pilots, aircraft navigational plotting boards like this one could be inserted into a space below the instrument panel in the cockpit and pulled out like a drawer, enbaling the referencing of information jotted down during the pre-flight briefing or navigational computation. The tops of these plotting boards could also be raised with the push of a small button, allowing access to other documents. In the case of this particular example, the contents from nearly seven decades ago are like a time capsule to a bygone era, their pages last flipped high above the Pacific Ocean in the waning days of the greatest war the world has ever known