In 1957, a movie titled The Wings of Eagles starring John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara winged its way across movie screens. Filmed in part on board Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, Florida, it told the story of naval aviator Frank W. “Spig” Wead and his efforts to advance naval air power during the 1920s. Some of the central scenes in the early part of the film include fistfights with Army pilots as the two services compete against each other in air races and distance flights. To be sure, film reflected fact to some extent, the air races of the Golden Age of Aviation pitting fliers in blue against those in green. Yet, interestingly, during 1923 there was an intraservice competition that grabbed headlines as Navy Lieutenants Harold J. Brow and Alford J. Williams strove to be the fastest man in the air.

They were among the hundreds of young men who flocked to Navy recruiting stations after the outbreak of World War I seeking to fight overseas in the new arena of warfare that was aerial combat. A native of Providence, Rhode Island, Brow had two years of service in the state’s National Guard before joining the Navy just four days after the United States declared war on Germany. He received his wings as Naval Aviator Number 571 at NAS Pensacola, Florida, on March 23, 1918 at the age of 23, his subsequent wartime service stateside at NAS Miami, Florida, and NAS Hampton Roads, Virginia. Older than Brow, Williams was a native of New York City and held a degree from Fordham University when he joined the Navy in December 1917, the pitcher that drew the attention of New York Giants manager John McGraw setting aside a promising baseball career to fight for his country. Like Brow, Williams was destined not to make it overseas, receiving his wings as Naval Aviator Number 1820 at Pensacola in December 1918, a month after the signing of the armistice ending World War I.

While much of the military demobilized, with soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines setting aside their uniforms and returning to civilian life, Brow and Williams remained in the service. Though their chances at combat had passed, aviation offered a challenging arena to test their skills honed in flight training over Northwest Florida skies. In a testament to his flying ability, Williams was selected to perform the Navy’s first inverted flight tests in a modified N-9 trainer over Pensacola in April 1919, just months after receiving his wings, the beginning of a long history of landmark experimental work that included developing tailspin and flat spin recovery methods. Meanwhile, in 1921 Brow received the honor of being chosen to lead Navy bombers in the well-publicized bombing tests against obsolete and captured German warships off the Virginia Capes.

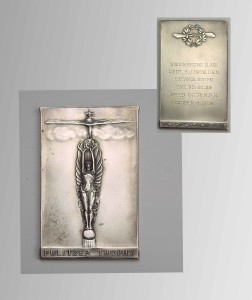

By 1922, both Brow and Williams were focused on air racing, which had become a popular spectator event as well as an arena to promote aircraft development. The premier race in the United States was the Pulitzer Trophy Race, which was sponsored by New York World publisher Ralph Pulitzer, an aviation enthusiast. The first race, which was held in 1920, was won by an Army pilot. The following year, the Navy CR-1 racer crossed the finish line first, but with Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company test pilot Bert Acosta at the controls. The 1922 Pulitzer Trophy Race took place in Detroit, Michigan, and this time the Navy entries included the CR-2 flown by Lieutenant H.J. Brow and the CR-1 flown by Lieutenant Alford J. Williams among the seven Navy airplanes entered in the race. “The grand derby of the air,” was how one newspaper described the Pulitzer Trophy Race in coverage leading up to the Detroit event, pointing out that every plane entered had reached over 200 M.P.H.

Unfortunately, Navy racers would not reach that mark in the race, which was won by Army Lieutenant Russell Maughan, who averaged 206 M.P.H. over the 160 mile course. Brow and Williams finished third and fourth respectively with average speeds of 193.2 M.P.H. and 188 M.P.H. They were more fortunate than Marine First Lieutenant Lawson H. Sanderson, who pulled out of the race due to engine trouble and had to make a forced landing in Lake St. Clair, tearing a wing off of the airplane, but leaving him uninjured.

In 1923, the Navy was again back in force for the Pulitzer Trophy Races, which on this occasion were held in St. Louis, Missouri. Over a course measuring some thirty miles less than the previous years, the Navy nearly swept the competition, claiming the top four spots with Williams averaging 243 M.P.H. in the R2C-1 to win the race. Brow finished second with an average speed of 241.8 M.P.H. in the R2C-1. Both eclipsed the existing world’s speed mark, setting the stage for a competition between the two at Mitchel Field on Long Island, New York, in early November 1923.

After delays caused by high winds, the two naval aviators commenced their aerial duel on Friday, November 2, 1923. Taking to the air in the same aircraft they had flown in the Pulitzer Trophy Race the previous month, Brow and Williams flew through hazy skies over a three-kilometer course, their altitude on the speed runs limited to 164 feet. On his first run, Brow reached a speed of 257.42 M.P.H., only to be beaten by Williams on his first run, during which he nipped him by just 1.19 M.P.H. As one newspaper columnist reported, while Williams was receiving congratulations from Army pilots at the field, Brow jumped into his plane for another go, reaching and average speed of 259.47 M.P.H. “The spectators held their breath as his plane shot through the air and the thrill of the day came on the second leg when…he sent his machine at the breath-taking clip of 4.4 miles per minute.” On the ground, statisticians figured that on his fastest run, Brow’s engine was turning at 2,800 revolutions per minute, unparalleled for the time in that an engine had not previously turned that fast for such a sustained period without going to pieces.

Two days later, the competition was renewed, an Associated Press reporter describing the scene. “Under a fair Indian summer sky, the two planes of bright marine blue were wheeled out upon the field.” First Williams topped Brow’s record, only to be surpassed by his friendly rival on his maiden flight of the day. Then Williams, who was scheduled to fly an exhibition over the Bronx, delayed his appointment and, wearing shirtsleeves and a helmet, climbed into the R2C-1 for another run. Narrowly avoiding a catastrophic accident when he flew through a formation of Army Martin bombers approaching Mitchel Field—“[I] yell[ed] to them to get out of the way,” he later recalled tongue in cheek—Williams landed having averaged a speed of 266.59 M.P.H. Though beat out for the world record, Brow could claim top speed of the day, his R2C-1 reaching 274.2 M.P.H. on one of his legs.

Williams’ record held for just over a year before the French pilot Florentin Bonnet eclipsed it on November 11, 1924, reaching an average speed of 278.11 M.P.H. in a Bernard-Ferbois V.2 monoplane. Not until 1947, when Commander Turner F. Caldwell flew the D-558-1 Skystreak on display in the National Naval Aviation Museum to an average speed of 640.663 M.P.H. over a 3-kilometer course at Edwards Air Force Base would a naval aviator again be the world’s fastest mortal.

Brow and Williams continued their distinguished service in naval aviation. In 1925, while practicing night approaches on board the Navy’s first carrier, Langley (CV 1), Brow’s aircraft stalled, giving him the unintentional distinction of making the first night landing on a U.S. Navy flattop. That same year, flying an NB-1 over San Diego Bay, he made test flights to develop a method for recovering from a flat tailspin, on one occasion crashing into the water and swimming away from the sinking aircraft. He retired from the Navy in 1947, having served in fighting, patrol, and scouting squadrons and in command positions at air stations. He died in 1982 and is buried at Barrancas National Cemetery.

Williams continued to make headlines, receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross for his work on inverted flight research, after which he resigned his commission in the Navy to accept a position as Aviation Sales Manager for Gulf Oil Company. To promote sales, he flew around the country in a brilliantly painted Grumman Gulfhawk II. Williams also wrote a syndicated column for Scripps-Howard newspapers, proving an outspoken voice in matters of the air. During this time, he joined the Marine Corps Reserve, leaving the service in 1940 with the rank of major. After the United States entered World War II, he was not called to uniformed service, but instead served as a technical consultant on fighter tactics to Chief of the Army Air Forces, General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold. Williams died in 1958, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.