Imagine if such modern staples of daily life as text messaging and Instagram had existed seventy-three years ago when, half a world away from the places they called home in the United States, military personnel and civilians at Pearl Harbor and surrounding installations were attacked by Japanese carrier aircraft. The worried mother in the heartland may have been able to hear a ring on her phone signaling receipt of a message from her sailor son and the wife of a serviceman living in the hills overlooking Pearl Harbor might have texted to those back home images of the attack as it occurred.

Of course, modern technology did not exist back then, news of the attack for most Americans coming on a Sunday afternoon listening to the radio, the words, “We interrupt this program to bring you a breaking news bulletin,” signaling a dramatic change from peace to war.

If there was something akin to text messaging, it was official naval messages that harried sailors typed out from the scene of the action, their contents reflecting the confusion and uncertainty that reigned in Hawaii during and after the attack. On board the aircraft carrier Lexington (CV 2), which was at sea en route to Midway to deliver Marine aircraft to that atoll, the ship’s executive officer Commander Wallace M. “Gotch” Dillon monitored the teletype machine as it rattled out message after message.

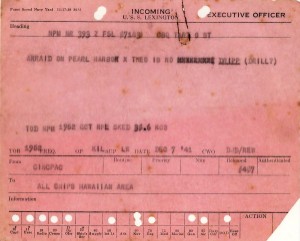

He saved the flimsy papers for the rest of his life and, reading them today in the files of the library at the National Naval Aviation Museum, one can only imagine what was going through his head. “AIRRAID ON PEARL HARBOR X THIS IS NO XXXXXXXXX DRIPP (DRILL?),” reads one, the typographical error revealing the duress under which the message was originally generated. Many at Pearl Harbor believed the air raid was only a prelude to an invasion of Hawaii itself, with messages like “ENEMY TRANSPORTS REPORTED FOUR MILES OFF BARBERS POINT XX ATTACK” and “ENEMY PARACHUTE TROOPS WILL WEAR BLUE DENIM AND RED INSIGNIA” fortunately proving incorrect. Other messages report further attacks against Manila in the Philippines and that Trans World Airlines aircraft had been instructed not to carry Japanese passengers for fear of sabotage. At 1935, 7:35 pm for civilians, came the message that resonated most for all aboard Lexington. “ORDERS MAY BE EXPECTED TO PROCEED TO INTERCEPT ENEMY.” This never materialized and Lexington returned to Pearl Harbor on December 13, 1941, her crew having to wait for another day to avenge the attack.

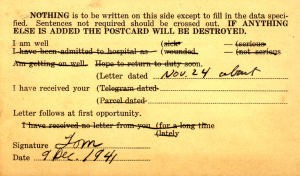

By that time, another Pacific Fleet carrier had come and gone. Enterprise (CV 6), which like Lexington, had fortunately been out at sea when the Japanese attacked, entered Pearl Harbor at dusk on the evening of December 8th, those on board witnessing firsthand the destruction wrought by the Japanese planes. By dawn the following morning she was gone, having refueled and taken on provisions under the cover of darkness. Left behind for mailing were hundreds of postcards with carefully prescribed instructions for completion, the one that went to the parents of Lieutenant (junior grade) Thomas Provost donated to the museum some years ago by his widow. By crossing out printed statements listed, he informed them he was well, had sent his last letter to them around November 24th, and would write again at the first opportunity. With receipt of this card dated December 9th, its contents brief and to the point like a modern text message, Mr. and Mrs. Provost received word that their son was alive and well, one of the fortunate ones in the wake of the “Day of Infamy.”