In the quarter century since it first took shape on the drawing board of architect Paul Chen, the Blue Angel Atrium has become one of the most recognizable areas of the museum. On any given day, visitors walk all around it and stare in wonder at the four A-4 Skyhawks, the successors to the pilots that flew them frequently signing autographs beneath the airplanes. The location has served as the venue for speeches by President George H.W. Bush and a concert by musician Jimmy Buffett in addition to various symposia and military ceremonies from personnel receiving their wings of gold to changes of command.

To be sure the seven story glass structure is a sight to behold, but it is the four aircraft hanging from the top of the atrium that are without a doubt its biggest stars. Whether bathed in sunlight on a bright Florida afternoon or lit up against a night sky, the diamond formation of aircraft is a stunning display and a fitting one given the fact that the Cradle of Naval Aviation is home to the Blue Angels Navy Flight Demonstration Squadron.

Like all airplanes in the museum’s collection, each of these has a story. So, in case you didn’t know…

The #1 and #3 aircraft hanging in the Blue Angel Atrium were accepted by the Navy on the same day (August 30, 1963) and the other two entered service in 1967.

Collectively, the four aircraft made 9 combat deployments to Vietnam, eight of them with the Navy and one with the Marine Corps.

The four aircraft have operated from the 8 different aircraft carriers that include Bon Homme Richard (CVA 31), Coral Sea (CVA 43), Enterprise(CVAN 65), Forrestal (CVA 59), Hancock (CVA 19), Independence (CVA 62), Oriskany (CVA 34), and Shangri-La (CVA 38).

Collectively, the four aircraft flew in 20 different Navy and Marine Corps squadrons before assignment to the Blue Angels. The #2 aircraft was with the squadron the entire twelve years that they flew the A-4 in flight demonstrations. However, in the case of one of them, there was no air show flying. Can you guess the imposter?

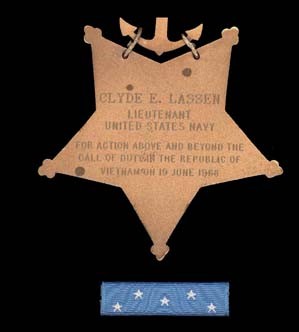

In the museum’s fifty year history, the likes of a President of the United States, Chiefs of Naval Operations, and pioneer astronauts have made visits to the museum for symposia or lectures. However, arguably the most moving event to ever occur within our walls took place on the evening of June 19, 1993. It featured six men whose fortunes had converged in the jungles of North Vietnam exactly 25 years earlier. They had not all been together since that night, when four of them launched into the dark sky in a UH-2 Seasprite helicopter and ventured deep into enemy territory to rescue the other two, who had ejected from their F-4 Phantom II fighter after being hit by antiaircraft fire during a combat mission.

Over the course of a few hours, the men revealed their memories and in recalling events that were not laughing matters when they occurred, they managed to add a touch of humor. For example, the audience chuckled hearing that Captain Zeke Burns, USN (Ret.), the F-4 radar intercept officer, outran his pilot, Captain John Holtzclaw, USN (Ret.), from their jungle hiding places to the rescue helicopter despite the fact that he had broken his leg during the violent ejection. The unassuming manner of the helicopter’s pilot, Commander Clyde E. Lassen, USN (Ret.), shone through as he described enemy fire coming at his helicopter, having to regain control of his aircraft after it hit a tree during the rescue, and returning to a ship off shore with very little fuel sloshing in the tanks.

It was this calmness, along with uncommon intrepidity, that made the mission successful, the heroic actions of Lassen resulting in his receiving the Medal of Honor for actions above and beyond the call of duty. At the end of the evening, Lassen rose to make a special presentation to museum director Captain Robert Rasmussen, USN (Ret.). He spoke about the Medal of Honor and how he really did not know the significance of the award before it was placed around his neck by President Lyndon B. Johnson. He told the hushed audience that he had rarely worn it and that he could think of no better home for it than the museum. With that, he passed the familiar award with its distinctive ribbon of white stars on a field of blue, to Captain Rasmussen, a fitting end to a memorable evening.

The six men would never be together again. Ten months later, Commander Clyde E. Lassen passed away, the victim of cancer. He is buried in Barrancas National Cemetery on board Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola, one of three recipients of the nation’s highest award for valor interred there.

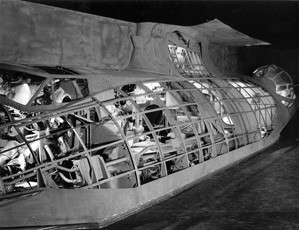

From the replica USS Cabot (CVL 28) flight deck and carrier island to the models of flattops arrayed around the museum, visitors have plenty to look at when it comes to the signature class of ships in the U.S. Navy since World War II. However, only one of the models gives the full flavor of the vastness of an aircraft carrier due to its construction of clear plastic down to the individual compartments from the top of the island all the way down to the bilge.

It is a well-traveled model, one that took shape in the pattern shop at the Puget Sound Navy Yard in 1945, a bustling place like other shipbuilding facilities around the country during World War II. The workers at Puget Sound were in the midst of a wartime period in which they constructed forty-three vessels and submarines and some 1,700 small boats. However, one of their primary roles given the yard’s location on the west coast was the repair and overhaul of ships from the Pacific war zone, among them the venerable carrier Enterprise (CV 6).

Although Puget Sound had no role in the construction of a carrier, personnel in the pattern shop set out to build a 1-ft.= ¼-in. scale model ofKearsarge (CV 33), which was launched at the New York Naval Shipyard in May 1945. The intent was not to make something that was as appealing to the eye as a model that showed a ship as she appeared underway, but instead to reflect the maze of compartments laid out below-decks. In this, it succeeded.

The model eventually found its way to Naval Air Station Pensacola, where museum director Captain Bob Rasmussen, USN (Ret.) remembers seeing it displayed in the lobby of Building 633 during his days as a flight student back in the early 1950s. Donated to the Naval Aviation Museum in August 1963, just two months after the institution opened its doors, the model has been on display ever since, not as flashy as those displayed around it, but one that draws the attention of most every visitor that has was walked through our doors.

The United States had been at war for just over seven months when a PBY-5B rolled off the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation assembly line. One of 225 of its type built for eventual delivery to Great Britain under the provisions of Lend-Lease, the career of this particular Catalina flying boat was destined to take a couple of unlikely turns, one of which preserved it for future generations after most of its contemporaries faded into history.

The first of these events was the inclusion of the airplane in a batch of 60 PBY-5Bs that were shifted from the Lend-Lease contract to U.S. Navy service, a move which took the airplane, its FP-216 identification number still painted on the tail in lieu of a U.S. Navy bureau number, not across the Atlantic, but to the Florida Gulf Coast. “Smoothness, precision and coordination are hammered into the embryonic aviator,” the 1943 edition of the Flight Jacket cadet yearbook at Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola described flying boat training. “Just how well the cadet ‘gets the word’ on watching two throttles, controlling propeller pitch, air speed and smelling wind direction and velocity from the choppy water is determined by his final check.” The platform for the training described was the PBY Catlina and thus FP-216 began making flights from the shores of Pensacola with VN-8D8A (Training Squadron (VN) 8A, Eighth Naval District).

On May 28, 1944, as Allied forces assembled overseas for the upcoming invasion of Normandy, flight operations on board NAS Pensacola proceeded at their frenetic wartime paces, the skies buzzing with the sounds of training planes in flight. Ensign Motter C. Pennypacker, Jr., nearing completion of his first year as a flight instructor with VN-8D8A, manned FP-216 along with five others for a training flight. Everything proceeded normally until the plane water looped while making a landing, which caused severe structural damage to the plane and fortunately only resulted in minor injuries to one of the men on board. Eventually towed ashore, the grounded Catalina, if to add insult to injury, was involved in a ground collision with another aircraft being towed along the seawall.

At the time of these incidents involving FP-216, the Survival Training Unit at NAS Pensacola, which during the war was involved in teaching flight students the skills and techniques they would require if forced down on land or at sea, was developing an exhibit to create a hands-on environment for instruction. One such teaching aid was already in place in the form of an SO3C Seagull aircraft positioned in a nosed-over crash position complete with a pilot mannequin with its head slammed against the instrument panel, a reminder to buckle shoulder straps. A group of junior officers, among them Lieutenant Jim Morrison, who later would spearhead fundraising to restore the airplane, came up with the idea of using FP-216. With PBYs then the primary platforms for air-sea rescue, the idea was to expose students to the interior layout of the airplane completely fitted out with survival gear. With some assistance from the Assembly & Repair Division, the wing and skin on the port side of the plane was removed and the grounded PBY was placed into the back wall of the building housing classrooms and exhibits. Interestingly, a period photograph shows an aircraft at the building that has FP-192 visible on the tail section of the airplane. However, in later years the tail section was removed and a data plate inside the cockpit of the fuselage clearly identified the hull as that of FP-216.

FP-216 remained in place until 1997, a popular exhibit for flight students as well as civilian visitors. That year, in the wake of the decision to close the Survival Training Exhibit, a team from the museum ripped the airplane out of the wall and placed it in storage. Not until 2001 was it moved to the museum’s restoration facility where it received corrosion control, metalwork, and painting. While this process was underway, volunteers and staff refurbished equipment removed from the aircraft while members of the PBY Catalina International Association scoured the world for parts to complete the interior, their efforts resulting in the current display of the airplane that fully depicts the interior of one of the venerable flying boats in its wartime configuration.

It is only fitting that the Navy’s official museum devoted to the history of naval aviation include something related to the man known as the “Father of Naval Aviation.” Indeed, the museum is honored to have in our collection the original Medal of Honor that Rear Admiral William A. Moffett received for his actions at Veracruz, Mexico, in 1914, as well as a sword presented to him by the crew of the battleship Mississippi (BB 41).

Moffett’s time as skipper of the battlewagon marked a completion of his conversion into one of the leading proponents of naval aviation, a startling transformation for an officer who one told an early aviator that flying airplanes was a profession for the crazy and foolish. However, on board Mississippi during the winter maneuvers in the waters off Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, in 1919, Moffett fully embraced the participation of aircraft in the operations at sea. Seeing that the battleship Texas (BB 35) sported a wooden flight deck atop one of her turrets for the purpose of experimenting with launching wheeled aircraft for used in spotting naval gunfire, Moffett ordered his crew to construct a similar arrangement on board Mississippi. He welcomed the use of wireless radio transmissions between aircraft and his gunner y officer, the coordinates of targets relayed from high altitude enabling Mississippi ‘s gunners to attain accuracy that was better than all other battleships in the exercises combined.

In the spirit of competition that existed between ships, such success bred a grateful crew flush with bragging rights that they could take with them ashore on liberty. As was customary when a skipper departed, the crew pooled their money to purchase a parting gift, in the case of Moffett presenting him with an ornate sword inscribed to him with appreciation for a “happy and successful two year cruise.”

Moffett kept the sword for the remainder of his life, which ended tragically in the crash of the rigid airship Akron (ZRS 4) in April 1933, at least one formal portrait photograph showing him holding the sword given to him by his devoted crew. Those feelings for their old skipper overshadowed one minor defect on the sword, the fact that in the engraving his last name is spelled incorrectly!

Like other institutions in other fields, museums have evolved in how they present history to the public. While to a certain extent artifacts behind glass cases remain, more and more visitors interact with the history about which they are learning, either through the technology of touch screens or in dioramas that immerse them in a particular moment in history.

The latter has become a popular way for the National Naval Aviation Museum to reach visitors and the first such diorama that we built is still going strong more than two decades after it was first conceived. The inspiration for the exhibit came from the childhood experiences of Museum Deputy Director Robert Macon, who during the late-1960s lived on Guam while his father served there in the U.S. Air Force. Just over twenty years removed from World War II, the island still contained an array of relics from the battle that occurred on the island in 1944. Macon and his friends would frequently venture into the jungle landscape, where on occasion he came across remnants of encampments, both American and Japanese.

After accepting the position of curator and deputy director at the museum in 1990, one of Macon’s first actions was to construct a diorama based on his childhood memories. Interestingly, it was initially not intended to be displayed at the museum, but was instead the museum’s entry into the exhibit area at the annual Pensacola Interstate Fair. Complete with tents outfitted with World War II equipment and an OY-1 Sentinel observation plane, the Pacific Island encampment was brought to life by a group of ensigns stashed at the museum awaiting the commencement of flight training. Dressed in period uniforms, they interacted with the audience and acted the part, especially when an air raid siren sounded. With a first place ribbon and much positive feedback, it was a no brainer that the exhibit needed to be reconstituted in the museum and it was.

Today, many components of the original exhibit remain, but there have been some enhancements. A stairway leading up to it from the museum floor is lined in part with replica sandbags to give visitors the feel of being in a bomb shelter. The OY-1 has been replaced by an FM-2 Wildcat that was pulled from the waters of Lake Michigan and remained in fairly good condition despite its extended underwater stay. During its service, the Wildcat actually spent time at Espiritu Santo, a Pacific island base like the one it now has a starring role in depicting.

Outside of the aircraft themselves, the Pacific Island exhibit is the most long-lived exhibit in the museum, one that has given the flavor of the World War II Pacific Theater to literally hundreds of thousands of people.

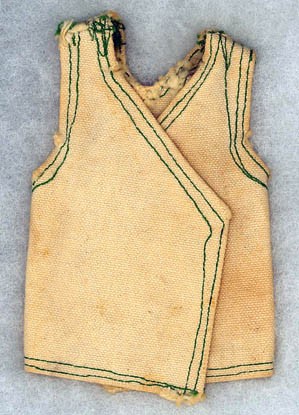

Anyone who has ever worn a tuxedo, and for most men that is at least once in their lives, “monkey suit” is a familiar slang term for the formal attire. The museum’s collection includes its own version of a “monkey suit,” but in our case the term is literal, a relic of the earliest days of space travel before naval aviators like Alan Shepard and John Glenn displayed the right stuff to borrow the phrase of author Tom Wolfe.

One of the longtime fixtures on board Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola was the Naval School of Aviation Medicine (later the Naval Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory), which was tasked with studying the effects of flight on the human body. In the late-1950s, at the dawning of the U.S. space program, the school became involved in evaluating some of the first primates that would be launched into space ahead of the first human astronauts. In preparation for the planned 1959 flight, twenty-five South American squirrel monkeys arrived in Pensacola for the beginning of tests to determine their adaptability for the project, one of the females standing out as the ideal one. Named Miss Baker, she joined an American-born rhesus monkey evaluated by the Army and named Miss Able in being selected for the flight.

On May 28, 1959, the two primates, each strapped into a canister that contained devices to monitor their vital signs, were placed in a capsule atop an Army Jupiter rocket positioned on the launch pad at Complex 26B at Cape Canaveral. At 2:39 AM the rocket roared aloft, carrying Miss Able and Miss Baker to an altitude of over 300 miles. Of the 16 minutes they were airborne, the two monkey’s spent nine minutes experiencing weightlessness. With their recovery after splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean by the fleet tug Kiowa (AT 72), the pair became the first living creatures launched into space by the United States and returned to Earth alive.

The two creatures were instant celebrities, a color photograph of them featured on the cover of the June 15, 1959, issue of LIFE magazine. Tragically, two weeks before the magazine went to press, Miss Able died on the operating table as doctors were in the process of removing an electrode from beneath her skin. Miss Baker, lived to the age of 27 years old, much of her time spent at the Naval Aerospace Medical Research Laboratory, where a window on the outside of the building allowed visitors to look at her in her cage. Mated to another primate in 1962, she lived in Pensacola until 1971, at which time she moved with her mate to the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Receiving visits and fan mail from school children until her death in 1984, she is buried on the grounds of the rocket center, where people still routinely leave a banana atop her gravestone.

It was the Navy’s connection to Miss Baker that resulted in the museum’s “monkey suit,” a small jacket similar to the one that appears on the cover of LIFE magazine, worn by one of America’s first space travelers.

There has long existed a connection between Hollywood and the U.S. Navy, the operations on the high seas providing exciting historical backgrounds for stories on the silver screen. The introduction of aviation to naval operations only heightened the attention of movie producers, with actors such as Clark Gable, John Wayne, William Holden, Mickey Rooney, and Errol Flynn starring in roles as naval aviation personnel.

When the Naval Aviation Museum opened its doors on June 8, 1963, the ceremony included its own Hollywood connection in the form of Naval Reserve Lieutenant Commander Jackie Cooper, who as a child actor was familiar to many as one of the kids featured in Our Gang shorts, which to later television audiences were broadcast under the title The Little Rascals. An Academy Award-nominated actor at the age of 9, Cooper joined the Navy in 1942. Accepted for officer training despite the fact that he lacked a high school diploma, he entered the V-12 program, first at Loyola University in Los Angeles and then at Notre Dame, the program’s purpose being to provide college educations for prospective officers.

Low grades and demerits prompted Cooper to leave the V-12 program and report to Great Lakes for recruit training, his wartime service not aboard a ship at sea, but as a drummer in a Navy band that toured the Pacific performing for the troops at island bases. Under the direction of Navy chief petty officer Claude Thornhill, the musicians called themselves “Thornhill’s Raiders.”

Honorably discharged in January 1946, Cooper resumed his acting career, one of his first roles Ensign Pulver in a production of Mister Roberts. Another naval role came on television in the series Hennesey, in which he played Navy doctor Lieutenant Chick Hennesey. In his efforts to obtain Navy cooperation for the series, Cooper worked closely with Navy public affairs, which renewed his interest in the naval service. Commissioned a lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve in September 1962, he made training and promotional films and recruiting spots for the sea service, eventually rising to the rank of captain. In 1970, he was honored as Honorary Naval Aviator Number 7, one of his earliest ties to naval aviation being when he stood on the steps of Naval Aviation Museum to serve as the Master of Ceremonies for its opening.

(Information on Jackie Cooper’s naval service drawn from James E. Wise, Jr. and Anne Collier Rehill, Stars in Blue: Movie Actors in America’s Sea Services (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997)