African Americans in the U.S. Navy During the Civil War

The Experiences of the Potomac Flotilla

Introduction

While many people know quite a bit about the exploits of the armies during the Civil War—those commanded by Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman and Joseph E. Johnston—the role of the U.S. Navy during the conflict is not as widely known. Many people know even less about the role of African American sailors in the Navy during the war and how the service helped to end slavery in the United States.

This essay summarizes the general role of the U.S. Navy during the Civil War: its mission, its size, and the challenges it faced. It then discusses African American sailors in the Navy and how they continued their heritage of service during the conflict. Then, the essay describes some of the ways in which the Navy helped to bring about Emancipation during the war. Finally, these strands are woven together with a consideration of the Potomac Flotilla, which was a small group of Navy vessels that operated within the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

The Navy and the Civil War

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, the U.S. Navy faced new challenges. In prior wars—most prominently the American Revolution and the War of 1812—the Navy had focused on commerce raiding and the construction of small ships for coastal defenses. An important ancillary to this strategy was permitting private vessels—privateers—to prey upon the enemy’s commerce. These strategies would not work for the Union during its fight against the Confederacy.

Not only would the Navy need to deal with Confederate ships on the high seas, it would have to blockade more than 3,500 miles of coastline, stretching from the Potomac River down to the Rio Grande. Along this coastline were about 200 harbors, inlets, and streams, all of which would need to be patrolled to prevent maritime Confederate commerce. Added to this responsibility was the need to secure and operate upon interior navigable rivers, where the Navy would provide logistical and fire support for Army forces. The Navy confronted a daunting task.1

To meet these challenges, the service would have to expand dramatically. As of April 1861, the Navy encompassed only 90 vessels. Of these, many were largely obsolete sailing vessels, unfit for combat service, though useful as receiving ships and tenders. The remaining ships were steam vessels, though the most capable of these were fit only for service in deep waters. At the outbreak of the war, only a handful were in U.S. waters. As such, they would be of less use for work close to the coast or on inland waterways. Over the course of the war, the Navy would add more than 500 new vessels to its registry, most of them steam-powered, stretching from the smallest gunboats to hulking, double-turreted ironclad monitors. By the end of the conflict, the fleet had expanded to upwards of 650 vessels in commission.2

Almost immediately at the outbreak of the war, the Navy had to manage a blockade of the Southern Coast. President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade in April 1861, and in July, Congress followed up with legislation enabling the executive to close Southern ports.3 Thus, legally speaking, the Navy could board ships and prevent war-making materials from entering Southern ports. Turning this into a reality, however, was a different challenge.

To carry out the President’s order, the Navy established several blockading squadrons, which divided the coastline of the Confederacy into different sectors. Initially, the Atlantic Coast Blockading Squadron, under Commodore Silas Stringham, encompassed the 1,000 miles of coast between Alexandria, Virginia, and Key West, Florida. To cover this area, Stringham began with a force of only 14 gunboats. A separate squadron bore responsibility for the Gulf Coast. In the fall of 1861, finding these areas of responsibility too large, the overall blockade was reorganized. Now, Commodore Louis Goldsborough took command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, which stretched from Cape Charles, Virginia, to Cape Fear, North Carolina. The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron covered South Carolina to Florida, and later, the Gulf of Mexico was broken into the East and West Blockading Squadrons.

The blockading squadrons faced numerous difficulties. Primarily, the Union Navy sought to interdict Confederate trade with nations abroad. Progress was slow, as the service needed to acquire ships that could match the seakeeping qualities of vessels seeking to run the blockade. The Navy had to develop tactics, as well, to catch these blockade runners. The blockade runners, for their part, adapted and began to adopt low-profile hulls painted gray in order to avoid detection. Not until late in the war would the Union Navy shut down Confederate trade. The squadrons also worked to stop local and coasting trade. This activity was quite important, as it prevented the movement of goods and people within the Confederacy, forcing commerce and movement to rely upon increasingly rickety railroads and a poor road network. Finally, both the North and South Atlantic Blockading Squadrons confronted fortified Southern port cities that were important not only for commercial purposes but also as political symbols. The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron faced Wilmington, North Carolina, where Fort Fisher would not fall until 1865. The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron worked with the Army in an attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina, which also would not fall until 1865.4

Naval leaders faced an immense challenge, which necessitated the expansion of the Navy discussed earlier. The Navy also had to surmount the challenge of technological innovation, with the widespread use of armored vessels known as ironclads, the advances in ordnance with the shell-gun, and changes in propulsion with the widespread adoption of steam power.

As the war continued, Union vessels would increasingly be designed for work close inshore, constructed with shallow drafts, double ends, and steam plants better suited for the work they faced rather than conventional confrontation on the high seas. New Confederate weaponry threatened the Navy, from submarines such as CSS Hunley to explosive charge–carrying boats such as the David class. Weapons such as then-called “torpedoes”—forerunners of today’s undersea mines—posed new threats and challenges for the Navy. The Navy also had to relearn how to deal with inshore and riverine combat in areas where Confederates could wait in ambush.

African American Seaman Joachim Pease’s Medal of Honor. Inscribed lettering on reverse reads: “Personal Valor/JOACHIM PEASE/(Colored) Seaman/U.S.S. Kearsarge/Destruction on the Alabama/June 9, 1864.” Pease served as seaman on board USS Kearsarge when she destroyed CSS Alabama off Cherbourg, France, on 19 June 1864. Acting as loader on the No. 2 gun during this bitter engagement, Pease exhibited marked coolness and good conduct, and was highly recommended by the divisional officer for gallantry under fire. Following Kearsarge’s return to the United States in 1864, Joachim Pease disappeared from the historical record. With his enlistment term expired, he was free to resume his life outside of the Navy. Where that led him is unknown (NHHC 1864-06-09).

Africans, African American People, and the U.S. Navy

Obviously, with such a large expansion in size, the Navy would have to find more men to add to its ranks. From 1861 to 1865, the officer corps more than quadrupled in size, from 1,300 officers to 6,700. The enlisted force grew from 7,600 men at the outset of the war to more than 50,000 by its end. Over the course of the war, more than 118,000 men enlisted and served.5 To meet this increasing demand for personnel, the Navy cast its enlistment net far and wide, to include the enlistment of African American men as sailors.

African and African American men had long served in the Navy and the merchant marine. Some scholars estimate that nearly one fifth of all American seamen in the first half of the 19th century were African American men. They had always been present aboard ship, and the nature of shipboard life made formal segregation difficult. Aboard a ship, everyone faced the same trials and tribulations. White and Black sailors alike dealt with the same captains, the same petty officers, the same adverse weather conditions, the same bad food, and the same perils. Collective work at crucial times—such as making sail or weighing anchor—helped unite crews in shared labor. The arcane argot and knowledge necessary to be a sailor also helped define the fraternity. In all of these ways, shared experience could work to diminish racial discrimination aboard ship.

However, racial distinction did exist aboard vessels. In the 18th and 19th centuries, African American men's roles were usually restricted to lower-level billets, such as cooks, servants, and musicians. This tended to set Black sailors apart from the rest of the crew. It should be noted, though, that so far as can be discerned, Black sailors were treated the same as White sailors of the same rate and were customarily paid the same.6

Unlike in the U.S. Army, the antebellum Navy did not prohibit the service of African American men outright (a ban, from the Secretary of the Navy, on their enlistment existed from 1798 until 1813, but was seldom observed). African Americans sailors had served in the Continental Navy and the early U.S. Navy after that. By the 1840s, the Secretary of the Navy capped the number of enlisted African American sailors at 5 percent of the manpower.7

The Navy drew upon these antebellum Black sailors to help man its vessels. About one fifth of African American people who enlisted at the start of the war had prior service at sea. Over the course of the war, African American sailors would come to make up around 16 percent of the Navy's enlisted manpower. This number was roughly twice that of the Army's. In absolute terms, this was somewhere around 18,000 sailors. Estimates have varied, though a modern authority places the number at about 20 percent of the enlisted force.8

African American sailors served with honor and dignity. A number of them received the Medal of Honor. Unlike in the Army, they received the pay commensurate with their rating; military discipline on ship also fell the same on both Black and White sailors. That said, however, no African American sailors were commissioned as officers or warrant officers. As before the war, they tended to be cooks, stewards, and musicians. Regardless of their prior experience at sea, they were often enlisted at the rating of “Landsman” rather than “Sailor.”

The Navy and Emancipation

Although the Civil War ultimately ended the institution of slavery in the United States, this process was contested, contingent, and did not happen all at once.

By September of 1861, Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy, declared that escaped or liberated enslaved African American people could enlist at the rating of "Boy," which was the service’s lowest rating. While this designation may appear to have racist connotations, it was also the naval rating for those without experience at sea. After that point, African American men who made it to Union vessels would often have the choice of enlisting aboard the respective ship.9

The presence of Union vessels close to the Southern coast made them into beacons of freedom for enslaved African American people. Escapees would often take small boats and voyage out to the blockaders. Once aboard ship, the formerly enslaved African American people would either enlist, or be dropped off in Union-controlled territory by the ship when it rotated off of its blockade station to resupply.

Indeed, in the testimony of Union sailors, it is unavoidable to come across mention of the Navy providing respite to enslaved Black people. Bartholomew Diggins, who served aboard USS Hartford, recalled that while going up the Mississippi River “we picked [up] many negroe [sic] slaves who would come out to the ships in small boats at every place we anchored.”10 Benjamin Gould kept a journal that detailed a generally constant stream of escaping enslaved people arriving on USS Cambridge. He noted they arrived in groups, with eight arriving on 22 September 1862, followed by 20 more two weeks later.11

In many cases, the crews of Navy ships would take a more active role in aiding African American people seeking freedom. William Park, aboard USS Essex on the Mississippi River, recorded in his diary that “we had a slave on board…who wanted” to retrieve “his son about 12 years old.” Sailors accompanied the enslaved man “30 miles back into the bush…where all the slaves was at work…In fact we could have brought the whole of them very easy.” Despite this inclination, Park lamented that “they all wanted to go with us but we had more on board than we had provisions for.”12 Surgeon Samuel Boyer, on blockade duty off the coast of South Carolina, recorded in his journal that “Cain and Sam, two contrabands who made their appearance on board this craft some time ago, came alongside in a canoe and reported that they had left nine colored brethren and sisters [behind]…our captain sent the 1st cutter after them to bring them on board.”13 Boyer also described that after a relative of an African American crewman died, “the carpenter at the request of the captain made a rough coffin for the body. Paymaster Murray and Ensign Thomas as well as 4 of our crew went to attend the funeral.”14

Crews would also do what they could to protect African American people in their ship’s proximity. Essex, for instance, changed its position in order to protect escaping slaves ashore from guerilla attacks. Essex’s position in the Mississippi River became known and it gained the reputation of being a place of refuge. When enslaved African American people emerged on the shore, Essex would “send Boats” to bring “them on board.” Because of this, Confederate guerillas sought to deter escapes through violence. William Park wrote how one morning “there was about 60 men women and Children” on the shore “when a Band of Guerillas came down and shot one of them[,] tied another one both hands and feet then threw him into the River.” Essex lay too far out on the river to intervene. After witnessing this horrific sight, the ship moved in “closer to the shore to prevent such scenes in the future.”15 This humanitarian act did not come without danger: the closer a ship lay to shore, the more likely it was to be ambushed by guerillas with small arms and field pieces. Furthermore, the closer in shore a ship lay, the more vulnerable it became to a sudden attack and boarding. So, when the Essex moved its anchorage, it was a move that came with significant risk.

The benefits of cooperation with African American people also extended to the crews of the Navy vessels. Black people kept a careful eye on Confederate activities and would frequently bring intelligence to Union vessels. This information extended from troop movements to the precise placement of Confederate torpedoes. For instance, William Park noted that one morning an African American person “brought word that the Rebels had been planting Torpedo’s during the night.”16 Other information provided included news of Confederate troop movements and the location of munitions, provisions, and other supplies. Edward Bacon, aboard USS Iroquois, wrote in his diary of asking contrabands to "bring off to us some Secesh grub, which they did."17 African American people also kept the Navy apprised of Confederate progress in converting the frigate USS Merrimack into the ironclad CSS Virginia.18

Typically, because vessels had high mobility, or could send a smaller boat ashore, the Navy could act with dispatch on this information. As Lieutenant Edward Hooker of the Potomac Flotilla described, information from African American people “induced me to attempt the capture of Major Lawson, C.S. Army, reported to have arrived home.” He dispatched 30 men under an acting master. The group “did not succeed, and an approaching the house the alarm was given…by dogs evidently trained for the purpose, and before the house could be surrounded the major escaped.” Despite failing to net Lawson, Hooker confiscated a quantity of bacon that had been prepared to Richmond.19 Thus, even if they did remain aboard U.S. Navy ships, African American people ashore played an important role in the service’s operations during the Civil War.

In at least one instance, an African American woman brought important technical intelligence to Union authorities. In March 1862, Mary Louvestre brought plans of CSS Virginia to Washington, DC, and delivered them to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Welles remembered this action with “much gratitude” and commended Louvestre for her “zeal and fidelity.”20

Despite those instances where crews showed empathy and recognition of shared humanity with African American southerners, racial animosity and tension could creep into these relationships. For many sailors, contraband African American people, who would receive food aboard ship without being subject to harsh naval discipline, pending being sent back ashore, became a source of resentment. Bartholomew Diggins recalled that aboard Hartford, many of the contrabands, in his view, “became quarrelsome, lazy and insolent. When they were brought up for any misconduct, the officers heard them with more favor than they did the crew.” In response to these perceptions, the sailors on Hartford “cut the fastening on a lot of rigging and spars under which” the African American people “slept on the spar deck, letting the whole come down with a rush upon them.” To underscore their displeasure, Diggins recalled how “one of the most insolent of them was caught by some of the men and thrown out of one of [the] forward ports overboard.”21 Overall, the Navy helped to end slavery and sailors could be sympathetic to the cause of emancipation, but underlying racial prejudice in the service remained persistent.

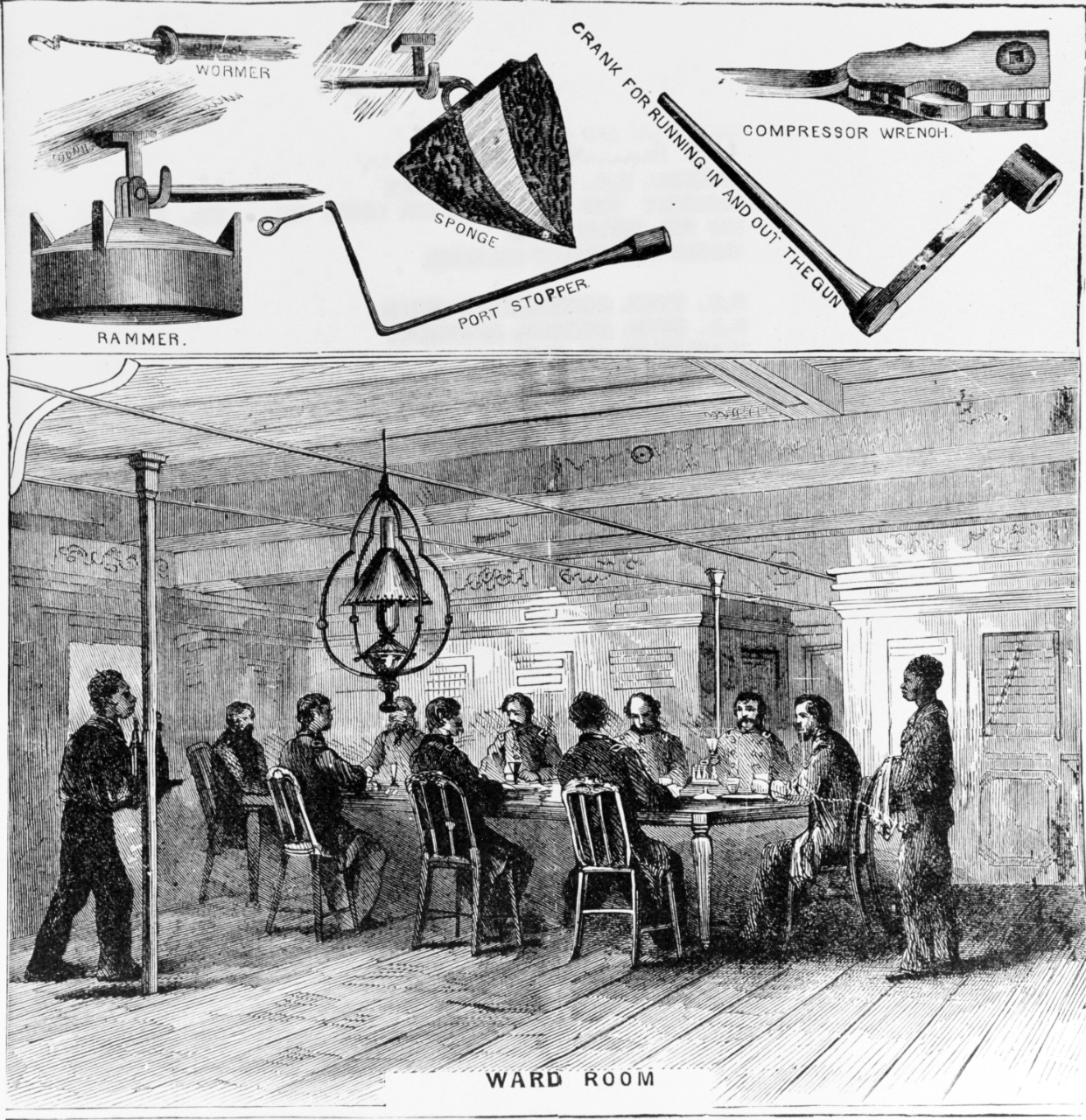

Line engraving published in The Soldier in Our Civil War, Volume II, page 187. It depicts scenes on board USS Monitor, probably at about the time she was completed in December 1862. The views include a view in the officers' wardroom, with African American messmen at work, and several vignettes of ordnance equipment (NH 58703).

The Potomac Flotilla

The operations of one small Navy unit illustrates the breadth of experience during the Civil War. Initially part of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, the Potomac Flotilla’s mission would change to meet emerging crises. It faced down Confederate batteries that had closed off riverine access to Washington, DC, and then spent the war involved in action against Confederate guerillas. African American people on shore proved critical to the flotilla’s operations.

The flotilla grew from humble beginnings and from the need to protect Washington. Abraham Lincoln's call for volunteer troops on 15 April 1861 in order to deal with the secession crisis prompted Virginia to leave the Union. Several days later, riots in Baltimore, where Southern-leaning mobs attacked the 6th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, underscored that Maryland was still a slave state and teetered on the brink of secession itself. These circumstances placed Washington in a precarious position and the need to keep maritime supply routes open became clear. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles ordered three mail steamers—Baltimore, Mount Vernon, and Philadelphia—to be purchased in order to help protect the Potomac. When Commander James H. Ward, then at the New York Navy Yard, suggested a "Flying Flotilla," Welles placed him in command.22 Ward arrived at Washington from New York with three steamers under his command: Thomas Freeborn, Reliance, and Resolute. In May 1861, the Flying Flotilla was established. The vessels were all smaller ferryboats and steamers, and were augmented by two larger screw sloops, Pocahontas and Pawnee.23

Welles, Lincoln, and others feared that Confederates could cut Washington off from marine transportation with a blockade of the Potomac River. In short order, the Confederates constructed batteries at various points along the Potomac River, the first of which was at Aquia. A major engagement took place on 1 June, when the Navy ships bombarded the Confederate shore batteries, with little effect.24 The Aquia battery was too far from the main channel of the Potomac to impede traffic seriously, but another battery at Mathias Point could cut off the river. It was in action against this battery that Ward fell in action on 27 June, hit in the abdomen with a musket ball while sighting a 32-pounder aboard Thomas Freeborn.25 The Confederates later abandoned the Mathias Point position because it was too isolated. Several months later, batteries sprang up at Evansport, Shipping Point, and Cockpit Point, as well as other places. The Potomac was now closed to Union traffic. The vessels of the Potomac Flotilla, renamed as such in August, sought to keep the river open, but they could not drive the Confederates away. In March 1862, the Confederates withdrew from the batteries as part of a strategic reconcentration in anticipation of their spring campaigning season.

Thus, after early 1862, the operations of the Potomac Flotilla took on a different tone. During the first two years of the war, it had focused on keeping the Potomac open for Federal traffic, which necessitated engagements against Confederate shore batteries and organized bodies of troops. With this threat removed, the flotilla began to bring the war to the enemy in earnest. The nature of combat shifted, as well, with the flotilla facing attacks from guerillas and irregulars, often leading to frustration.

The Potomac Flotilla sought to interdict a robust smuggling trade between Maryland and Virginia. The creeks and rivers of the upper Chesapeake Bay provided many locations for smugglers to hide, and nearly any boat could answer that purpose. An officer of the Potomac Flotilla recalled that the Confederates used "fast schooners or pungies" and "the eastern-shore three-masted canoe, which, in a good breeze, could outsail anything afloat." Such simple craft needed little in the way of specialized facilities or support. The same officer observed that "in a general way, I would say that every town, village, hamlet and barn, situated on or near the bank of a creek, river, inlet or stream, that afforded proper shelter and cover from observation, with a depth of water equal to a foot or more at low tide" served as a port for smugglers. Likewise, networks of smugglers and Confederates kept an eye on Union activities. The same Union officer noted that people ashore "established a system of signals that enable the parties concerned to maintain a regular communication" and thereby avoid interception.26

In order to harass Confederate operations, the Potomac Flotilla cooperated with the Union Army to launch raids in the area, and passed information back and forth with their land-based counterparts. These forays fell heavily upon the citizens of the Northern Neck. Union troops would range widely, with the Potomac Flotilla landing them largely at will. Often, raids netted only a few prisoners, quantities of tobacco and other crops, and resulted in the destruction of a handful of boats. Sometimes, though, raids could net larger returns. A four-day expedition in April 1864 along the Rappahannock River resulted in the destruction of two ferryboats, seven lighters, three pontoon boats, 22 skiffs and canoes, 200 oak beams, 500 cords of wood, and 300 barrels of corn. Also captured were 22 boats, 1,000 pounds of bacon, and sundry other articles. This particular raid also carried five White refugees and 45 African Americans people to safety. Another raid up Carter's Creek drove off Confederate cavalry, then burned their camp, the stores of grain they had been collecting, and 11 boats. Landing parties brought back to the Potomac Flotilla 17 more boats, livestock from the area, and a number of contrabands. In general, these raids disrupted Confederate operations and demonstrated Federal authority to the residents. While not decisive in their impact, they certainly damaged Confederate morale and logistics in the area, making it problematic for Confederate authorities to govern the Northern Neck.27

Here, as well, the Potomac Flotilla drew upon the information that African American people could provide. As mentioned earlier, enslaved and free people could help direct the Flotilla to stocks of supplies, men hiding out, and boats hidden in creeks or laid up ashore. Furthermore, enslaved African American people essentially voted with their feet and left with the Union forces, thereby depriving the Confederacy of their labor while adding it to the Union cause. Confederate General Robert E. Lee, for one, complained that even "a small body of troops…could do nothing against the bands landed from boats, who could avoid them on every occasion." The Union forces knew precisely where to strike, because they were "thoroughly informed" of every Confederate movement "by traitors and negroes in the country."28

These operations were not without risk. The Potomac Flotilla operated within a confined area; therefore, it became easier for Confederates to ambush the steamers in a variety of ways. As noted earlier, Confederates would mine the rivers with torpedoes. Detonated primarily by contact fuses, these explosives could sink or damage Union vessels and were difficult to detect. The men of the Potomac Flotilla sought whenever possible to destroy the devices ashore, but it proved impossible to prevent them from being planted. In one expedition up the Rappahannock River in 1864, for instance, several torpedoes detonated in the water while gunboats fished six more duds out of the river.29

Gunboats close ashore made tempting targets for organized Confederate forces. For much of 1862 and 1863, Confederate irregular John Taylor Wood, grandson of former U.S. president Zachary Taylor and nephew of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, who held commissions in both the Confederate States Navy and Confederate States Army, led operations against Union vessels in the Northern Neck area. Under his direction, Confederate sailors placed wheels on boats, allowing them to be shuttled back and forth across the Northern Neck, so that they could emerge to strike in either the Potomac or Rappahannock Rivers. These harassing attacks disrupted Union commerce and proved to be a great nuisance. Wood's greatest success came on 23 August 1863, when with a force of around 100 men, he captured the steamers Satellite and Reliance.30 The capture prompted a massive Union effort on both land and sea to find and neutralize the vessels so that they could not be used by the Confederates. Ironically, Wood's raid also awakened the commanders of the Potomac Flotilla to the risk of surprise attack, which led to increased readiness and standing orders on how to repel boarders, making further Confederate attacks much more difficult. These men continued to lurk in the area. In January 1864, Lieutenant Edward Hooker fired three shots from his rifled gun to disperse "a number of men, several on horseback, having with them five large boats, three of which were on wheels" that had collected on the south bank of the Rappahannock River.31

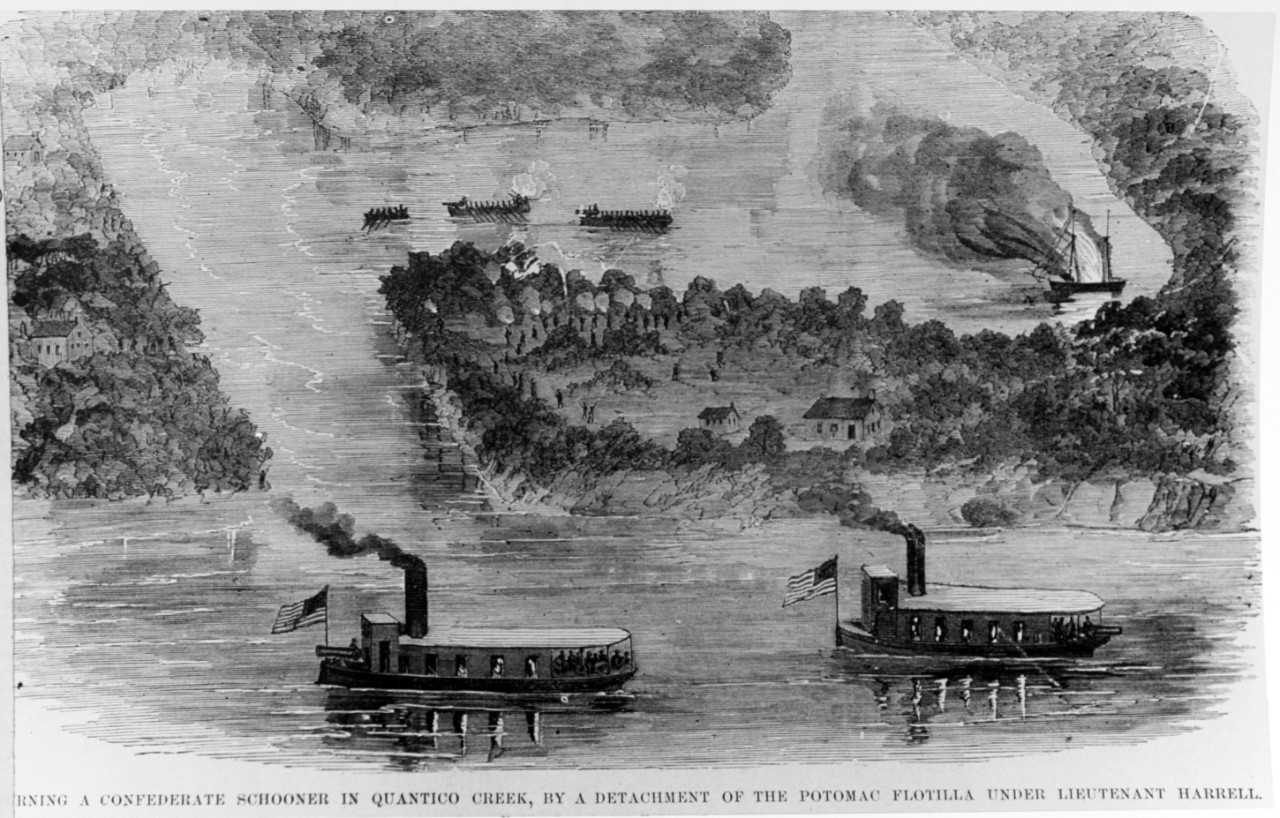

“Burning a Confederate Schooner in Quantico Creek, by a Detachment of the Potomac Flotilla under Lieutenant Harrell.” Engraving published in The Soldier in Our Civil War, Volume I, page 233. This may depict the action of 11 October 1861, in which Lieutenant Abram D. Harrell of USS Union, with three boat crews, cut out and burned a Confederate schooner in Dumfries Creek, on the Potomac River, Virginia (NH 59244).

The Potomac Flotilla, however, encountered guerillas much more often than organized formations such as Wood’s. Although the Flotilla ran across company-size formations of Confederate troops, it usually drove them off with well-placed artillery fire. Guerillas lying in wait to ambush passing Union vessels were a much more persistent and dangerous problem. Guerillas would operate on their own or sometimes in conjunction with the Confederate army, which could supply artillery pieces upon occasion. Encounters were usually brief but intense. Ensign Hallock, commanding Eureka, described how a force "lying in ambush, most unexpectedly opened with rifles and a piece of light artillery." Eureka returned fire. In a report to the Secretary of the Navy, Commander Foxhall A. Parker described how "for some ten minutes (during which time this lasted), she was one sheet of flame, the 12-pounder being fired as fast as a man would discharge a pocket pistol."32

Guerilla warfare embittered the sailors aboard the Flotilla, who found it difficult to distinguish between friend and foe, all the while expecting a sudden volley from the riverbanks. Thomas Nelson, an ensign at the time, wrote of how "these rascals" would "profess the most ardent affection for the Union cause," point out the location of smuggled goods, then arrange "to assemble his vile companions at some point down the creek, where under perfect cover they would be absolutely safe from harm while murdering the crew of a boat exposed in the open."33

It all amounted, in Nelson's opinion, to "the meanest, most contemptible and wretched kind of fighting ever recorded anywhere in civilized warfare." In his view, "every man of character and principle" had left "for the front," leaving only "another class of individuals, spiritless and degenerate, who were hiding when the men went to the front and came out after the coast was clear." In other words, he thought that the men left on the Northern Neck were shirkers and opportunists, men without character or scruple. Nelson claimed that these types "engaged in the lucrative business of smuggling; and incidentally, when the opportunity came, to indulge in vandalism, piracy, and murder."34

Confederate general Robert E. Lee expressed a similar opinion. When locals asked for military assistance, Lee responded that Union raids were "distressing in the extreme, and are more to be deplored because they cannot be prevented." He refused to send troops, claiming that "the population have more strength within themselves and more power to protect their persons and property than they are willing to realize." Help from the Confederate army obviously was not coming, and a hint to Lee's hostility came in the next sentence of his letter: "I have always heard that there were a great many men in that country who should have been in this army, but could not be got. I think the least they can do would be to turn out and defend their own homes."35 As Lee’s letter demonstrates, Union raids undermined morale on the Confederate home front and also led to requests that Confederate commanders spread their already thin manpower even further.

These sentiments give some suggestion about the nature of the Potomac Flotilla's war after 1862. This was a small-scale, dirty fight, in which both sides viewed the other as ungentlemanly and making use of unfair advantages. And indeed, the Potomac Flotilla's operational impact fell largely on Confederate civilians. Unable to engage the enemy directly in most cases, the Flotilla demonstrated Federal authority by disrupting Confederate operations, destroying Confederate supplies, and driving off Confederate troops whenever possible. But, perhaps most importantly, the Potomac Flotilla provided an avenue of freedom for many of the enslaved African American people who lived on the Northern Neck, and many of them also found employ in its vessels.

—Peter C. Luebke, PhD, Histories Branch, NHHC History and Archives Division

____________

1 Robert M. Browning Jr., From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: The North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1993), 142; and Donald Canney, Lincoln’s Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861–1865 (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1998), 17.

2 Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, 1–2, 143.

3 Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, 5–6.

4 On the blockading squadrons see: Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear; Robert M. Browning, Jr., Success Is All That Was Expected: The South Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2002); and Robert M. Browning, Jr., Lincoln’s Trident: The West Gulf Blockading Squadron during the Civil War (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2015). On the constriction of the Confederate coastal trade see David G. Surdam, Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the Civil War (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2001).

5 Browning, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear, 200.

6 W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 32, 69.

7 https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/diversity/african-americans/chronology.html

8 Joseph P. Reidy, “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War,” Prologue, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Fall 2001). Accessed online.

9 Barbara Brooks Tomblin, Bluejackets and Contrabands: African Americans and the Union Navy (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2009), 16–17.

10 Sailing with Farragut: The Civil War Recollections of Bartholomew Diggins, ed. George S. Burkhardt (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2016), 55.

11 Diary of a Contraband: The Civil War Passage of a Black Sailor, ed. William B. Gould IV (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002).

12 Katherine Bentley Jeffrey, Two Civil Wars: The Curious Shared Journal of a Baton Rouge Schoolgirl and a Union Sailor on the USS Essex (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2016), 101–2.

13 Naval Surgeon: Blockading the South, 1862-1866: The Diary of Dr. Samuel Pellman Boyer, eds. Elinor Barnes and James A. Barnes (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1963), 254.

15 Jeffrey, Two Civil Wars, 123.

16 Jeffrey, Two Civil Wars, 127–28.

17 Double Duty in the Civil War: The Letters of Soldier and Sailor Edward W. Bacon, ed. George S. Burkhardt (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009), 40.

18 Anna Gibson Holloway and Jonathan W. White, “Our Little Monitor”: The Greatest Invention of the Civil War (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2018), 24.

19 Edward Hooker to Foxhall A. Parker, 9 March 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5, 403.

20 Holloway and White, “Our Little Monitor,” 24.

21 Sailing with Farragut, 55–56.

22 For a brief biography of Ward, and discussion of the notable history of the ship named after him, follow this NHHC link.

23 Mary Alice Wills, The Confederate Blockade of Washington, D.C., 1861–1862 (Parson, WV: McClain Printing, 1975), 15–17.

24 Wills, The Confederate Blockade of Washington, D.C., 28–29.

25 Wills, The Confederate Blockade of Washington, D.C., 36–37.

26 Thomas Nelson, “Echoes and Incidents from a Gunboat Flotilla,” Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Commandery of the District of Columbia, War Papers 78, Read 1 December 1909, reprinted in Military Legion of the Loyal Legion of the United States (Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1993), 54: 150–51.

27 Foxhall A. Parker to Gideon Welles, 22 April 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5: 411–12; Foxhall A. Parker to Gideon Welles, 3 May 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5: 414; and Edward Hooker to Foxhall A. Parker, 30 April 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5: 415.

28 Robert E. Lee to James Seddon, 26 June 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records, Series 1, Vol. 40, Part 2, 689.

29 Foxhall A. Parker to Gustavus Vasa Fox, 12 May 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5: 421–22.

30 Roger A. Davidson, Jr., “Yankee Rivers, Rebel Shore: The Potomac Flotilla and Civil Insurrection in the Chesapeake Region” (PhD. Diss.; Howard University, 2000), 246–47.

31 Edward Hooker to Foxhall A. Parker, 16 January 1864, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5: 389.

32 Foxhall A. Parker to Gideon Welles, 22 April 1864, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series 1, Vol. 5, 411–12.

33 Nelson, “Echoes and Incidents from a Gunboat Flotilla,” 147.

34 Nelson, “Echoes and Incidents from a Gunboat Flotilla,” 147.

35 Robert E. Lee to James Seddon, 26 June 1864, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records, Series 1, Vol. 40, Part 2, 689.