The Navy Department Library

Writing U.S. Naval Operational History 1980–2010:

U.S. Navy Mine Countermeasures in Terror and War

by Scott C. Truver, Ph.D.

When Senior Historian Michael Crawford of the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) invited me to prepare a paper on the “needs and opportunities in U.S. Naval History in the post–World War II” period, my first thought was: “Doesn’t he know? Political scientist . . . not historian?”

To be sure, I had taken several history courses while at college. However, I wondered about the relevance of “Renaissance and Reformation”—I was thinking about becoming a Lutheran minister—to my proposed NHHC “needs and opportunities” topic, which was:

Operations—the Navy’s security roles in reference to China and Southeast Asia, Africa, South America, and Europe, particularly since 1980, and the Navy’s role in counter-piracy since the 1820s.

So we met, and he assured me that all would be good.

We also agreed to rethink the discussion of counter-piracy since the 1820s and focus on the 1980 to 2010 period. The goal was to provide a perspective of the “post-Vietnam War, post–Cold War, post-9/11” Navy and assess how Navy operations have been addressed by means of a historiographical survey of the English-language literature:

- Identify what has been published on the subject of Navy operations from 1980 to 2010, including counter-piracy ops (operations)

- Explain the broader historical context and the subject’s historical significance

- Map out the scholarly landscape by reviewing everything of significance published on the subject, and

- Identify needs and opportunities to help set the agenda for the research and writing of the history of U.S. Navy operations for the next 20 years

His use of “Navy” operations and not “naval” or “maritime” meant that I was not to address the other two sea services—the U.S. Marine Corps or Coast Guard—just the U.S. Navy.

Nevertheless, I remained concerned by the inclusion of “everything of significance.”

Thus, one of my initial objectives was to set boundaries to the problem, to determine what exactly “Navy operations” and “everything of significance” could mean. I did a preliminary search of NHHC holdings, resources available at the Naval War College and Naval Postgraduate School libraries, the Center for Naval Analyses (CNA) library, the Library of Congress and JSTOR (Journal Storage), and Google Scholar, Google Chrome, and Bing. I focused only on

operations—I did not include the much more numerous Navy, joint force, and international exercises—and came up with 158 identifiable/named operations from 1980 to 2010: There might well be more but there will not be fewer. These are listed in Appendices 1, 2, 3 (sources for these are in Appendix 1) and are summarized here:

|

|

| 1980–89 | 49 |

| 1990–99 | 85 |

| 2000–2010 | 24 |

|

|

| Peace operations/forward presence | 15 |

| Humanitarian assistance/disaster relief | 15 |

| Freedom of navigation | 3 |

| Maritime interception | 3 |

| Counter-piracy | 3 |

| Noncombatant evacuation | 26 |

| Show of force | 49 |

| Contingent positioning | 20 |

| Combat | 24 |

|

|

| Show of force | 49 |

| Noncombatant evacuation | 26 |

| Combat | 24 |

| Contingent positioning | 20 |

| Humanitarian assistance/disaster relief | 15 |

| Peace operations/forward presence | 15 |

| Counter-piracy | 3 |

| Maritime interception | 3 |

| Freedom of navigation | 3 |

|

|

| Mediterranean | 51 |

| Arabian Gulf | 32 |

| Africa | 27 |

| Western Hemisphere | 18 |

| Pacific | 14 |

| Indian Ocean | 6 |

| Southwest Asia | 4 |

| United States | 3 |

| Europe | 2 |

| Red Sea | 1 |

The 1990–99 period was the busiest with 54 percent of the total ops. The show-of-force ops were the most frequent with 31 percent. And, as would be expected, the Mediterranean/Arabian Gulf ops comprised most—53 percent—across all ten regions.

The challenge was multiplied by what I call “embedded operations.” This refers to an overarching operation under which subordinate operations were carried out. For example, Operations Sharp Guard and Decisive Enhancement from 1992–98 in the Mediterranean/Balkans region had 11 embedded ops:

- Sharp Vigilance 1992

- Maritime Guard 1992–93

- Deny Flight 1993–95

- Provide Promise 1994

- Joint Endeavor 1996

- Decisive Edge 1996

- Deliberate Force 1996

- Deliberate Guard 1996–97

- Joint Guard 1996

- Joint Forge 1997–2001

- Deliberate Forge 1997–98

| show of force | |

| show of force | |

| show of force | |

| contingent positioning | |

| peace operations/forward presence | |

| show of force | |

| combat | |

| show of force | |

| peace operations | |

| show of force | |

| show of force |

There was one other, but less extensive, instance of embedded ops—Continued Hope, Africa/Somalia 1993–95: Show Care, More Care, and Quickdraw. Still, individual bibliographical searches had to be conducted for each operation, using each of the nine search engines noted above and numerous key words and phrases for each, to ensure that I captured “everything of significance.” A quick assessment of time to complete was about 1,200 hours.

I again met with Michael: How can we cut this down and still meet the NHHC’s goals?

Because of my interest in naval mine warfare (MIW),1 I suggested, and he agreed, to focus on two U.S. Navy mine countermeasures operations in the post-1980 era.

The first was the 1984 “Mines of August” state-sponsored terrorist mining crisis in the Red Sea and the Navy’s Operation Intense Look response.2

The second was Operation Candid Hammer in 1990–91, an embedded op to Desert Shield/Storm show-of-force, contingent positioning, and major combat operations. The last time the Navy confronted a similar mining event was off Wonsan, North Korea, in October 1950, when 3,000 Russian mines kept a United Nations amphibious task force at bay and prompted task force commander Rear Admiral Allen E. Smith to lament: “We have lost control of the seas to a nation without a navy, using pre–World War I weapons, laid by vessels that were utilized at the time of the birth of Christ.”3

Michael reminded me that the focus of the effort remained on the historiography of these two operations, not the operations themselves. My revised tasking was now:

- Identify what has been published on the subjects Operations Intense Look and Candid Hammer (and other Arabian/Persian Gulf MCM ops in Desert Shield/Storm 1990–91)

- Explain the broader historical context and Navy mine warfare’s historical significance

- Map out the scholarly landscape by reviewing everything of significance published on operations Intense Look and Candid Hammer

- Identify needs and opportunities to help set the agenda for the research and writing of the history of U.S. Navy mine warfare

In that regard, then, let me first address broader historical context and Navy mine warfare’s historical significance.

Historical Context and Significance

Sea mines and the need to counter them have been constants for America since Bushnell’s Turtle in 1776.4 Mines figured prominently in the Civil War, Spanish-American War, both world wars, Korea, Vietnam, several Cold War crises (including at least one hoax), and in Operations Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom. In 2016, traditional navies as well as maritime terrorists have at their disposal mines and underwater improvised explosive devices to challenge military and commercial use of the seas.5

These “weapons that wait” are the quintessential global asymmetric anti-access/area-denial threat, pitting our adversaries’ strengths against what they perceive as our naval and maritime weaknesses. They can be put in place by virtually any platform—aircraft, surface vessels and craft, submarines, and even ferryboats—and their low cost belies their effectiveness. World War I–era contact weapons bristling with “horns” can be as dangerous as highly sophisticated, 21st-century computer-programmable multiple-influence mines that can fire from the magnetic, acoustic, seismic, and pressure “signatures” of their victims.

In 2016, perhaps as many as a million sea mines of more than 300 types are in the inventories of more than 50 navies worldwide, not counting U.S. weapons. More than 30 countries produce and more than 20 countries export mines. Even highly sophisticated weapons are available in the international arms trade. The Navy’s potential adversaries hold mines and mining in high regard: Russia is thought to have upward of 250,000 mines; China, 80,000 to 100,000; North Korea, about 50,000; and Iran, between 3,000 and 6,000 weapons.6 Worse, these figures are for sea mines, proper; they do not include underwater improvised explosive devices, which can be fashioned from 50-gallon drums and discarded refrigerators—virtually any container.

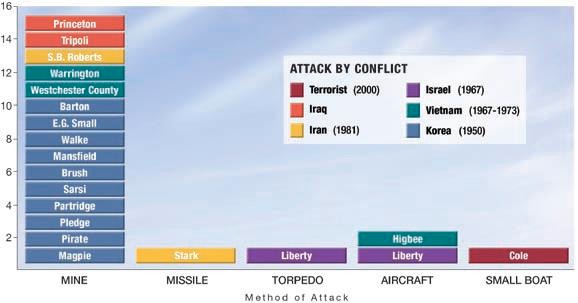

And, the Navy’s experience attests to the seriousness of the mine threat: Since the end of World War II, mines have severely damaged or sunk four times more U.S. Navy ships than all other means of attack. Yes, four of these 15 mine victims were minesweepers clearing the way for U.N. naval forces during the Korean War, but that tragically underscores the dangers from mines—even MCM experts are at risk.

Source: U.S. Navy N85 and PEO LMW, 2009

Operation Intense Look, 19847

The use of mines during the Arabian Gulf “tanker war” had only begun to ramp up and the mine strikes of the reflagged tanker MV Bridgeton and frigate Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58) were several years away, when commercial vessels reported suspicious underwater explosions in the Red Sea in July and August 1984.

At least 16—and perhaps as many as 19—merchant vessels transiting the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea as far south as the Bab el Mandeb claimed they had been mined. Various extremist groups avowed responsibility for planting mines in the international waterway—Islamic jihad being one of the more vociferous. Inasmuch as the first victim was the Soviet-flagged Knud Jesperson on 9 July, the Soviet Red Star military newspaper had another take on what it called “American aggression and imperialism in the Red Sea”:8

- Washington and its NATO allies are expanding their military influence in the Red Sea. They are mining the Red Sea in order to control Arab countries.

- Using the excuse that they plan to clear mines, NATO forces are expanding their military presence in the Red Sea and the Middle East.

Responding to actual Egyptian and Saudi requests, with Riyadh being particularly concerned about the safety and security of pilgrims making the annual Hajj to Mecca, U.S. Navy mine countermeasures and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) teams joined an international mine hunt to search for the sources of the explosions. Egypt, France, Italy, Great Britain, The Netherlands, and the Soviet Union deployed mine-sweeping and mine-hunting vessels and supporting EOD divers.

The U.S. Navy deployed four RD-53D airborne mine countermeasures (AMCM) helicopters from Helicopter Mine Squadron Fourteen (HM-14) equipped with the advanced AQS-14 mine-hunting side-scan sonar––this was the first real-world deployment of the “Q-14” ––in addition to legacy in-service mine-sweeping systems. Responding to Saudi requests to sweep the ports of Jidda and Yanbu, the Commander Mine Warfare Command divided U.S. forces into two detachments. The first was supported by the Middle East Force flagship La Salle (LPD-31) and focused on sweeping those ports as well as the Bab el Mandeb to ensure safe passage for the aircraft carrier America (CV-66) and her escorts transiting from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean.

The second swept middle sectors in the Red Sea, supported by the coastal hydrographic survey ship Harkness (T-AGS-32). Harkness embarked an Atlantic Fleet EOD side-scan sonar detachment, and the amphibious transport Shreveport (LPD-12) supported the AMCM helos deploying the Q-14 mine-hunting sonars. However, U.S. MCM forces detected no mines.

The U.S. involvement in theater was from 13 August to 1 October 1984, less than two months.

International MCM forces swept several mines, including ordnance that dated to before World War II. Moreover, the British recovered, rendered safe, and exploited a recently deployed weapon––the absence of sea growth indicating it had not been in the water long––an advanced Soviet multiple-influence mine dubbed “99501” from markings on the mine case. It was of a design that heretofore had never been seen in the West.

It was later determined that Libya’s navy had acquired at least 16 of the advanced mines from East Germany (Moscow was reportedly furious with East Berlin), which had been deployed from the stern ramp of a Libyan commercial ferry, Ghat. Manned by a Libyan navy crew and the head of the Libyan mine-laying division, she entered the Red Sea southbound from the Suez Canal on 6 July, declaring she was carrying “general cargo,” returning northbound at the canal on 23 July.

“In light of the ease with which terrorists demonstrated their ability to mine this important international choke point,” mine warfare historian Tamara Moser Melia concluded:

MCM quickly became the focus of international concern. Studies soon noted the importance of coordination of international MCM forces and national integration of mobile air, sea, and undersea MCM forces, the lessons repeatedly learned by U.S. MCM forces since Wonsan. The overall effect of such low-intensity mine warfare by terrorist organizations and the Third World reminded many nations of their own vulnerability to mines.9

Operation Candid Hammer/Gulf War MCM, 1990–9110

As it turns out, the actual title of the 1990–91 Desert Shield/Desert Storm–embedded MCM operations proved difficult to determine, with “Candid Hammer,” “Desert Sweep,” “Desert Clean Up,” and “Arabian/Persian Gulf MCM Ops” used by various sources. Furthermore, some

characterized Candid Hammer as an “exercise” while others as an “operation.” Dates were uncertain, too, although a “mid-August 1990 to early October 1991” period for the overall U.S. Navy MCM/EOD deployment and operations seems reasonable. Nevertheless, these ambiguities complicated the Desert Shield/Desert Storm and post–Desert Storm bibliographical searches, compared to Operation Intense Look.11

The need for U.S. and multinational Coalition partners’ MCM assets in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm was clear from the outset, given the use of mines by both sides in the Iran-Iraq war and the Navy’s experiences during Operation Earnest Will—Navy surface warship escorts of re-flagged merchant vessels. MCM deployment planning commenced immediately after Saddam Hussein captured Kuwait on 2 August 1990.

The six AMCM helicopters from HM-14 were ready to deploy to the Persian Gulf via strategic airlift on 4 August, but, because of priorities in airlift requirements, they did not depart Norfolk Naval Air Station until 4 October. Once in-theater, however, HM-14 was flying mine-sweeping training operations beginning on 11 October.

EOD detachments deployed to the Gulf in mid-August and immediately began in-theater training with multinational Coalition MCM forces. This training included the Desert Saber advance EOD MCM rehearsal/exercise in support of a planned amphibious assault north of Ash Shuabah on the Kuwait coastline that was cancelled and redirected as an amphibious raid on Faylaka Island. That, too, was cancelled because of the mine events of 18 February. EOD MCM operations began on 12 February 1991, and channel-clearance operations began when the ground war ended on 27 February.

Avenger (MCM-1, commissioned in 1987) and three 1950s-era ocean minesweepers (MSOs)––Adroit (MSO-509), Impervious (MSO-449), and Leader (MSO-490)––were transported onboard the U.S.-leased Dutch heavy-lift ship, Super Servant III, leaving Norfolk on 29 August and arriving at Bahrain on 3 October. The availability of such heavy-lift ships for surface MCM deployments is critical, as it significantly reduces wear and tear on ships and crews during long transits to overseas mine crises. After completing in-theater training and preliminary surveys, the MCM vessels commenced mine-hunting and -sweeping operations in suspected mine danger areas in the Gulf on 16 February 1991, a month after the air war began.

On 18 February 1991 two U.S. warships––Tripoli (LPH-10), which ironically had embarked the Navy’s HM-14 AMCM helicopters, and the guided-missile cruiser Princeton (CG-59)––suffered mine strikes. Two Italian-made Manta bottom influence mines attacked Princeton (actually one was a sympathetic firing several hundred yards away from the first, which detonated right under the cruiser’s keel) and a single LUGM-145 contact mine holed Tripoli. Although Princeton restored some strike and anti-air warfare capabilities (within 20 minutes or two hours, depending on the source), she ultimately was a mission kill and had to be towed to port. Despite a 16-by-20-foot gash below the waterline on her starboard side, Tripoli continued AMCM flight ops for another five days.

By all accounts the Iraqi use of naval mines was extensive and well planned. Moreover, because of a lack of focused intelligence, the Coalition did not know the extent and

sophistication of the enemy’s mine-laying efforts until after the Iraqi surrender. Then, the Iraqi military provided detailed charts showing the location and types of mines in ten minefields and lines, extending from off the Kuwait/Saudi border north to just west of the Ad-Darah oil fields. Following receipt of Iraqi mine charts on 4 March, concerted minefield clearance operations involving all MCM assets began in earnest with three goals: (1) open normal commercial shipping channels and ports; (2) sweep known minefields; and (3) complete area clearance of the Kuwaiti coast and the northern Gulf.

During the post-conflict MCM operations, six other countries joined the United States and United Kingdom assets: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the Netherlands. Initially without the United Kingdom, the European countries formed an independent Coalition of MCM forces under the aegis of the Western European Union (WEU), with Belgium being the first to begin operations in March 1991. The U.S. and U.K. MCM forces continued joint operations until mid-April, when the Royal Navy’s ships also joined the WEU Coalition. The Japanese operated independently, but with assistance from U.S. EOD forces, after entering the gulf in June. The WEU countries completed their MCM operations 20 July; the United States and Japan completed theirs in early October.

Naval historian Edward J. Marolda noted: “These mine countermeasures ships were critical to the success of the naval operation because the Iraqis had established a minefield with almost 1,300 magnetic, acoustic, and other mines. The ships (and ship-based mine-countermeasures helicopters) cleared lanes through what they believed were the minefields.”12

HM-14 was called off the MCM task on 17 June and completed redeployment to Norfolk on 8 July. Avenger returned to the United States in August, and the three MSOs returned via heavy-lift ship in November. Guardian (MCM-5) self-deployed and arrived in mid-June 1991, remaining in the gulf until the spring 1992. This was the beginning of a constant U.S. Navy MCM presence there, with surface vessels, AMCM helicopters, and EOD MCM detachments deployed to the region.

Of the nearly 1,200 mines destroyed by Coalition MCM forces through October 1991, 200 were sophisticated acoustic/magnetic-influence bottom mines, including the Manta bottom mines that attacked Princeton. After hostilities ended, Iraq reported that it had laid 1,167 mines of all types. Caitlin Talmadge noted Operation Candid Hammer apparently cleared 907, or 78.6 percent, of the original mines, “an impressive rate of clearance.”13

Lieutenant Commander Colin K. Boynton challenged the “impressive” assessment. “These operations were performed under permissive conditions against the easiest of mines to sweep (moored contact mines) and more importantly, the mine hunters had an Iraqi chart showing mine locations in their possession.”14

Everything of Significance

With that as prelude, I began a focused search to build the bibliography of “everything of significance.” (See Appendix 4.) I revisited the nine original sources––NHHC; Naval War College and Naval Postgraduate School libraries; the Center for Naval Analyses library; the

Library of Congress and JSTOR; and Google Scholar, Google Chrome, and Bing. The Library of Congress was difficult to maneuver, and many hours with JSTOR resulted in little of value; in fact, I culled only three publications:

- C. H. Stockton, “The Use of Submarine Mines and Torpedoes in Time of War,” The American Journal of International Law 2, no. 2 (April 1908): 276–84.

- Bradley A. Fiske, “Naval Preparedness,” North American Review 202, no. 719 (October 1915): 847–57.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, “The Future of the Submarine,” North American Review 202, no. 721 (December 1915): 505–8.

Remarkably, Google Scholar identified many useful “hits.” But there was much chaff to winnow: A 14 May 2016 search of “US Navy/mine warfare/Operation Intense Look/Red Sea/1984” resulted in about 13,400 items to be reviewed. A similar search for Operation Candid Hammer produced much fewer results––three––and only a handful more when the search was broadened to “Desert Shield/Desert Storm Arabian/Persian Gulf War MCM operations 1990–91.”

The “mother lode” was the mine warfare bibliography constructed and maintained by Greta E. Marlatt, senior research librarian, Dudley Knox Library at the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California. If a publication has the words “sea mine” associated with it, I have no doubt that Greta has it chronicled. I am particularly thankful for her excellent, cheerful, and long-suffering bibliographical assistance to this project. Likewise, Dr. Timothy O’Hara, research scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses, searched the CNA library and archives for this project.

General Articles

The search turned up 215 articles related to Operation Intense Look, published between 9 July and 21 October 1984, but only 13 for Operation Candid Hammer/Gulf War MCM operations that spanned a year. Most of Operation Intense Look articles were “today’s news,” reporting what had transpired in the previous 24 hours or so, and thus should not be considered history by any stretch of the imagination. However, they were secondary sources for the more scholarly articles and publications.

Three articles published well after the Royal Navy found the Soviet/East German/Libyan mine and the Mines of August crisis ended have served as unofficial histories of the event. (Other than command histories of ships and helicopter squadrons, the only government document that discusses the Red Sea crisis in an historical context is the 1992 Mine Warfare Plan.15) These were the U.S. Naval Institute (USNI) Proceedings/Naval Review “Mines of August” article (May 1985); Jan Breemer’s “Intense Look: U.S. Minehunting Experience in the Red Sea” (August 1985);16 and retired Royal Navy Captain John Moore’s overview––“Red Sea Mines a Mystery No Longer,” Jane’s Naval Review (1985), which provides good information from the United Kingdom’s perspective. These have been referenced numerous times in subsequent publications that focus on naval mine threats and mine countermeasures requirements, capabilities, plans, programs, technologies, and operations.17

Among what must be the many tens of thousands of articles and publications related to Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm, the 13 articles specifically addressing mine countermeasures topics in Desert Shield/Desert Storm/Candid Hammer did provide historical perspectives, mostly lessons re-learned about the threat and the requirements for effective countermeasures.

For instance, Vice Admiral Stanley Arthur and co-author Marvin Pokrant’s “Desert Storm at Sea” in the May 1991 USNI Proceedings summarized what would be their book, Desert Storm at Sea: What the Navy Really Did, published in 1999, which devotes significant discussion of MCM. Two months later, U.S. Navy Captain J. M. Martin focused sharply on lessons “We Still Haven’t Learned” in the July 1991 USNI Proceedings, even as post-hostilities MCM “sweep” ops continued in the gulf. Likewise, Lieutenant Ernest Fortin, USNR, addressed the nature of the mine threat––“Those Damn Mines” in the February 1992 Proceedings––and how to counter it. In the October 1992 Proceedings, EOD Commander R. J. Nagle outlined the difficult challenges that the Navy’s EOD forces confronted in the gulf. Finally, writing in the Summer/Fall 1992 Amphibious Review, Carle White discussed how the Navy’s MCM assets addressed the shallow-water threat.

As noted, there was an important international component to the Shield/Storm/Candid Hammer MCM operations. David Foxwell had four articles (one with David Brown) in the International Defense Review––“The Gulf War in Review: Report from the Front” (5/1991); “MCM and the Threat Beneath the Surface” (7/1991); “Mine Warfare in an Uncertain World” (5/1992); and “Naval Mine Warfare: Underfunded and Underappreciated” (2/1993)––that addressed the challenges from the allies’ perspectives. Similarly, Anthony Preston’s “Allied MCM in the Gulf” (Naval Forces 4/1991) and Vice Admiral Josef De Wilde’s “Mine Warfare in the Gulf” (NATO’s Sixteen Nations 1/1992) remind readers that the global aspects of the threat demand collaboration and cooperation among friends.

Books

I could find no book-length historical treatment specific to either Operation Intense Look or Operation Candid Hammer/Gulf War MCM––like, for example, the Naval Historical Center’s history of mine-sweeping operations in North Vietnam, Operation End Sweep.18 Instead, several significant discussions were found in publications dealing with the broader focus. I address these according to the operation.

Operation Intense Look

David Crist’s Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran (2013) weaves a riveting story in chapter 13, which begins (235) “. . . [in] the morning of July 6, 1984, the small cargo ship Ghat left Libya on its way to the Eritrean Port of Assab. The round-trip journey through the Suez Canal normally took eight days, but nothing about this trip was routine. Instead of the usual cargo of foodstuffs and crated goods, Ghat carried advanced Soviet-made naval mines designed to detonate in response to the mere sound of a passing ship. Rather than her normal civilian crew, Libyan sailors, including the commander of Muammar Gaddafi’s

mine force, manned the pilot house. Once in the Red Sea, the sailors lowered the stern ramp and hastily rolled the mines off into the water.”

Gregory Hartmann and I collaborated on the 1991 update of his original 1979 edition of Weapons That Wait: Mine Warfare in the U.S. Navy. The discussion of Operation Intense Look relies heavily on “Mines of August,” but was updated to early 1991 (and thus does not include discussion of MCM in Desert Shield/Storm/Candid Hammer). New materials included conjecture that some of the Libyan-laid “99501” mines had only half-explosive charges, which was to ensure ships would be damaged but not sunk, and that Libya had specifically requested advanced weapons from Moscow to bolster Libyan coastal defense.19

Howard S. Levie’s Mine Warfare at Sea (1992) devotes just three pages to Intense Look and provides little that is new.

Tam Moser Melia’s “Damn the Torpedoes” (1991) provides better operational information, but in only two pages.

Operation Candid Hammer/Gulf War MCM

Anthony Cordesman and Abraham R. Wagner allocated eight pages to this operation in their 1,000-page The Lessons of Modern War, Volume IV: The Gulf War (1996), but they provided excellent treatment of the MCM activities (888). “Mine warfare was one of the few areas where the long pause between Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait and the beginning of Desert Storm acted to Iraq’s advantage. Iraq used the time to deploy an extensive set of minefields off of the coast of Kuwait, which affected both the Coalition’s options for amphibious warfare and many of its other naval operations.” They provided detailed information on the mine threat, mine fields and mine lines, and the capabilities of the Navy (890) ––“The U.S. Navy had significant problems dealing with the Iraqi mine threat.”–– and its international MCM Coalition partners (892)–– “The British force took the lead in most of the mine countermeasures operations during Desert Storm” They concluded: “In short, mine warfare must be taken seriously from the start of a crisis” (897).

Marvin Pokrant’s Desert Storm at Sea: What the Navy Really Did (1999) devotes chapter 9 to mine countermeasures, a good deal of chapter 12 to post-hostilities mine clearance, and all of chapter 15 to “Observations on Mine Countermeasures.” Particularly important was its treatment of the role Vice Admiral Stanley Arthur, Commander U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, played in planning and execution of the MCM ops plan. He provides perhaps the best insight of the lack of intelligence about the mine threat, the Tripoli and Princeton mine strikes, U.S. and MCM Coalition partners’ capabilities, mine-clearance ops, and lessons learned (231): “Just as Iraq paid a price for allowing the Coalition to build up its forces unhindered for five months, the Coalition paid a price for allowing Iraq to lay mines without opposition. Once mines are in place, locating and clearing them under the guns of the enemy will always be hard and time consuming.”

Edward Marolda and Robert Schneller’s Shield and Sword devoted significant space to the treatment of the Iraqi mine threat, the U.S. Navy and Coalition MCM assets and capabilities, and pre-/post-conflict operations (322):

During the first three months of the mine-removal operation, the European mine clearing forces performed as would have been expected in a NATO conflict. Operating sophisticated ships and equipment, by mid-May the well-trained and experienced European seamen had destroyed or otherwise neutralized 750 sea mines. The Belgian and French mine hunters destroyed nearly 500 of them. The French mine hunter Sagittaire performed skillfully, neutralizing 145 mines in only 20 days. The U.S. and British forces destroyed fewer mines during the early months of the operation, in part because they were more concerned with clearing the existing lanes to the coast of Kuwait than systematically removing mines from identified minefields.

The European MCM forces finished their share of the mine clearance task on 20 July 1991. The U.S. Navy and the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force completed their MCM operations on 10 September 1991. Guardian (MCM-5), the last remaining MCM ship in gulf waters, departed on January 1992.

Finally, Andrew Lambert’s “The Naval War” chapter in The Gulf War Assessed (1992) provides a detailed analysis of the naval campaign generally, but offers sharp judgment from a U.K./Royal Navy/European perspective about U.S. Navy MCM operation (127):20

The major weakness of the USN lay in its limited mine countermeasures (MCM) force. With two new classes under construction, the USN had to rely on ships from the early 1950s and their solitary new Mine Countermeasures Vessel (MCMV), the USS Avenger. The strength in experience of RN and European MCM forces gave them a clear role, and made their presence a matter of urgency if the USN was to operate safely in waters which had already seen one mine campaign [1980s Tanker War].

These four books make a significant contribution to the historiography of Desert Shield/Storm MCM operations.21

Center for Naval Analyses Reports

I call out CNA because of its unique position as the Navy’s think tank, a provenance extending back to the Operational Evaluations Group of 1945, if not earlier.

Three Center for Naval Analyses reports figure into the historiography of mine warfare in Candid Hammer/Desert Shield/Desert Storm, but not Intense Look.22 Sabrina Edlow and colleagues provided a chronology of U.S. Navy mining (as opposed to mine countermeasures) generally (April 1997). Specifically with regard to Desert Storm, CNA notes (1),

the United States employed naval mines during the opening days of Operation Desert Storm. Commanders were not allowed to conduct anti-surface warfare against questionable transitors within Iraqi territorial waters and, as a last resort, requested permission to mine. Four A-6s from USS Ranger [CV-61] sortied, but only three returned. (In all prior military uses of mines, the mining occurred toward the end of conflict—here it’s at the initiation of the allied offensive.) On-

scene commanders recalled no impact on Iraqi operations from this mining effort. They chose to discontinue mining operations.

Dwight Lyons Jr. and CNA colleagues discussed “The Mine Threat: Show Stoppers or Speed Bumps” (July 1993) and concluded (30), “the lesson from Desert Storm is not that mine fields are impenetrable, but that if you ignore the threat, you pay for it.”

The third is Ralph Passarelli, et al., Desert Storm Reconstruction Report, Volume IV: Mine Countermeasures (U), Research Memorandum 91-180, October 1991. This remains classified.

Command Histories

Squadron and ship command histories provide some insight into the “deck-plate viewpoint” in both operations:

- John T. Hall (FFG-32): “After receiving urgent tasking, USS JOHN L. HALL got underway on 19 August and proceeded at best speed to Port Said, Egypt for a second southbound passage of the Suez Canal. . . . Shortly after midnight on 22 August, USS JOHN L. HALL entered the Suez Canal arriving at Port Suez by mid-morning on 23 August. Immediately exiting the Canal, USS JOHN L. HALL proceeded at best speed to gain visual contact on the Soviet Naval Task Force headed south in the Red Sea. For the next month, USS JOHN L. HALL conducted national interest surveillance operations against the LENI[N]GRAD (CHG-103) and her escorts. These operations were also in conjunction with Operation INTENSE LOOK, which was the joint U.S., French, British and Dutch Mine Countermeasure Operation in the Red Sea.”

- Shreveport (LPD-12): “. . . in response to orders received calling for embarkation of Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron FOURTEEN, with four RH-53D helicopters. USS SHREVEPORT had been assigned as the support ship for Airborne Mine Countermeasures in conjunction with Operation ‘Intense Look’ in response to the mining of the Gulf of Suez and the Red Sea. . . . On the 10th of August, SHREVEPORT began her transit to the Gulf of Suez. . . . Arriving at Port Said on the 15th, SHREVEPORT embarked Egyptian pilots and immediately commenced her passage of the Suez Canal as an individual ship. The passage was completed in the record time of seven hours and forty-five minutes and SHREVEPORT continued south to her operating area off Ras Shukheir, Egypt, in the Gulf of Suez. Enroute on the 16th . . . SHREVEPORT anchored off Ras Shukheir on the 16th and was joined by USNS HARKNESS. The remainder of the day was spent conducting briefings aboard SHREVEPORT for commencement of mine hunting operations on the 17th. For the next thirty days, mine hunting operations continued in the Gulf of Suez from sunrise to sunset making use of available daylight hours.”

- Helicopter Support Squadron Four: “[W]hile embarked in USS NASSAU through 11 Aug, the HC-4 Det set impressive standards by meeting 100 percent of assigned operational commitments. On 14 Aug 84, three days after the return of the NASSAU Det, X-4 was tasked with yet another unique deployment by providing support to operation

‘Intense Look.’ This deployment again demonstrated squadron versatility and the range of the aircraft capabilities, by providing responsive logistic support to this high visibility task force.”

The following command histories of ships and helicopters deployed to Intense Look and Candid Hammer/Gulf ops were not available or could not be accessed to meet schedules:

- AMCM Helicopter Squadron Fourteen, 1984, 1990–91 (classified)

- Adroit (MSO-509), 1990–91

- Avenger (MCM-1), 1990–91

- USNS Harkness (T-AGS-32), 1984

- Impervious (MSO-449), 1990–91

- Leader (MSO-490), 1990–91

Government Publications

In April 1992, the Department of Defense submitted its Final Report to Congress: Conduct of the Persian Gulf War, mandated by Title V, Public Law 102-25. It concluded that the Iraqi mine threat affected almost all naval operations during the Persian Gulf Conflict. From the outset, the principal mission of Coalition MCM assets was to clear a path to the Kuwaiti coast for naval gunfire support and a possible amphibious landing. Post-conflict assessments noted the Iraqi minefields were not placed to maximize their effectiveness and Iraqi forces deployed many mines improperly. Nevertheless, mines had considerable effects on Coalition maritime operations in the Persian Gulf (273, 286).

The May 1991 Department of the Navy/Chief of Naval Operations report, The United States Navy in “Desert Shield/Desert Storm,” served as a stepping stone in the development of the Navy’s first post-Cold War mine warfare plan. The conflict had

. . . again illustrated the challenge of mine countermeasures (MCM) and how quickly mines can become a concern. Because of the difficulty of locating and neutralizing mines, we cannot afford to give the minelayer free rein. Future rules of engagement and doctrine should provide for offensive operations to prevent the laying of mines in international waters. Our Cold War focus on the Soviet threat fostered reliance on our overseas allies for mine countermeasures in forward areas. The MCM assets of our allies––on whom we have relied for MCM support in NATO contingencies for years––provided their mettle in the Gulf . . . highlighted the need for a robust, deployable U.S. Navy MCM capability (61).

The January 1992 Mine Warfare Plan: Meeting the Challenges of an Uncertain World (U), was produced initially at the request of the Assistant Chief of Naval Operations (OP-03) but, as a result of increased awareness of the mine threat, the Chief of Naval Operations approved the plan and the programs it championed. “I believe there are some fundamentals about mine warfare that we should not forget,” Admiral Frank B. Kelso II noted in October 1991 (1). “Once mines are laid, they are quite difficult to get rid of. That is not likely to change. It is probably going to get worse, because mines are going to become more sophisticated.” Admiral Kelso was echoing the

statement of Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest Sherman, following the Wonsan MCM debacle of October 1950:

[W]hen you can’t go where you want to, when you want to, you haven’t got command of the sea. And command of the sea is a rock-bottom foundation of all our war plans. We’ve been plenty submarine-conscious and air-conscious. Now we’re going to start getting mine-conscious beginning last week.23

The objective of the 1992 plan was to put mine warfare within what later that year would be the . . . From the Sea strategic context. It surveyed post-World War II mine crises, including Operation Intense Look and Gulf War MCM ops, and it examined the changed strategic context, the nature of the global mine threat, enduring as well as emerging requirements, in-service capabilities to meet these needs, programs to address gaps and shortcomings, and resources to carry, bringing reality rather than rhetoric to the nation’s mine warfare mission area.

Academic Materials

In addition to a handful of international law-related articles––Elsadig Yagoub A. Abunafeesa, “The Post-1970 Political Geography of the Red Sea Region with Special Reference to United States Interests” (1985); Juden Justice Reed, “‘Damn the Torpedoes!’: International Standards Regarding the Use of Automatic Submarine Mines” (1984); and Ronnie Anne Wainwright, “Navigation through Three Straits in the Middle East: Effects on the United States of Being a Nonparty to the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea” (1986)––that touched upon the Red Sea mine crisis, if only tangentially, there has been a surprising number of mine warfare papers at war colleges and postgraduate schools. However, there is little that is new, and most use the Mines of August and Desert Shield/Desert Storm/Candid Hammer experiences to advocate for policy and programs.

For example, Lieutenant Commander Colin K. Boynton––“Operations to Defeat Iranian Maritime Trade Interdiction” (2000)––relies on previous discussions of Candid Hammer, such as they are, to counter Iranian use of mines in some future crisis. Lieutenant Commander Jason Gilbert––“The Combined Mine Countermeasures Force: A Unified Commander-in-Chief’s Answer to the Mine Threat” (2001)––highlighted past MCM challenges to argue for a revitalized international/maritime partners approach to combined MCM warfighting. Finally, Dr. Raymond Widmayer––“A Strategic and Industrial Assessment of Sea Mine Warfare in the Post–Cold War Era” (1993)––outlined a strategic framework for a robust mine warfare industrial base.

Needs and Opportunities to Help Set the Agenda

This survey of the historiography of two U.S. MCM operations reveals what might have been expected, a priori. As much as mines have had strategic, operational, and tactical impacts, MCM remains a niche warfare area––even more so when the Navy’s mines and mining are brought into the equation. The episodic nature of the threat, with sometimes years between events, generates an “out of sight, out of mine” philosophy. So it seems for histories of mine warfare operations, too.

There are the challenges of working U.S. Navy subjects that have classified materials. The CNA library has “thousands” of classified materials/reports/message traffic relating to Desert Shield/Desert Storm MCM, but I had no access to them.

That begs the question: Where to look for mine-warfare historical resources within the U.S. Navy? This is problematic, given the challenges of a fragmented warfare community with no single champion.24 Mine Warfare in the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations––the Navy’s headquarters––is centered in the Director of Expeditionary Warfare, but other naval warfare sponsors have overlapping and sometimes competing responsibilities for ships, helicopters, and unmanned systems.

There is no single mine-warfare voice in the operating forces, and the mine warriors suffer from organizational churn. In the acquisition community, an emphasis on mine warfare has all-but been eliminated from various program executive officer organizations from the mid-1990s through 2011:

- PEO (Project Executive Office)-MIW—created specifically to make MIW well and give it a competitive edge—MIW exclusive, no other warfare area

- PEO-MUW (Mine and Undersea Warfare)—mines listed first

- PEO-LMW (Littoral and Mine Warfare)—mines listed last

- PEO-LCS (Littoral Combat Ship) [MIW not even in the title]—some MIW “codes” were excluded altogether, e.g., PMS-408 (EOD)

Before 2006, the Commander Mine Warfare Command (COMINWARCOM)––in Charleston, South Carolina, and Ingleside, Texas––had operational control. Then the Navy disestablished it and stood up the Navy Mine and Antisubmarine Warfare Command––at San Diego, California––which commanded mine warfare as a secondary mission, but still at the flag officer level. The Navy disestablished that command in 2015 and established Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Command––still in San Diego––for ships and weapons. The operating force responsibility for the AMCM helicopters resides in the Commander, Naval Air Forces––San Diego––but the two AMCM helicopter squadrons are located in Norfolk, Virginia. And, the Naval Expeditionary Combat Command––Little Creek, Virginia––has had explosive ordnance disposal cognizance.

Conducting historical research in mine warfare thus looks to be a “Where’s Waldo?” evolution.

It does not help when the community shoots itself in the foot. Mine warfare expert George Pollitt explained,

When COMINWARCOM was in Charleston, there was an MIW archive kept at the Naval and Mine Warfare Training Center (NMWTC). This archive had operational data going back to before [World War I]. When COMINWARCOM moved to Corpus Christi, the archive was culled and the part that was retained was stored in boxes in the SECRET vault at COMINEWARCOM. I was told that, when COMINEWARCOM was disestablished, all the remaining archive was destroyed.25

Looking ahead, since 1992 there has been no book-length publication focused solely on the history of mine warfare in the United States and elsewhere (Hartmann/Truver, Levie, and Melia).26 However, much has transpired since then: MIW vision; strategy; threats; requirements; capabilities; programs; and operations. The U.S. Navy confronted an Iraqi mine threat in Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003),27 but nothing like 1990–91, and in May 2008 Tamil Black Tiger commandos used limpet mines to sink the (ill-named) MV Invincible (A-520), a Sri Lankan navy cargo ship loaded with explosives.28

Perhaps it is time to update/revise Weapons That Wait.

My experience focusing on the historiography of Operations Intense Look and Candid Hammer/Gulf War MCM ops could easily be repeated in the other 156 or so global U.S. Navy Operations from 1980 to 2010 outlined at the beginning of this paper. Official sources will remain difficult to access due to classification, and where to locate materials remains uncertain. A first step would be to take advantage of NHHC resources and the Navy library, as well as the Naval War College, Naval Postgraduate School, and (if access can be granted) CNA libraries. It should be expected that the names and dates of specific operations might not be correct. In this effort for Intense Look/Candid Hammer, I relied on numerous secondary sources, which at times had contradictory information.

At the end of the day, then, the issue is not whether we will experience a mining event, but when and where it will happen and whether we will be ready to defeat the threat. There are more than a million sea mines of more than 300 types in the inventories of more than 50 navies worldwide, not counting terrorist mines and underwater improvised explosive devices. I recall something about either learning from history or repeating it.

And, in that regard, I have no doubt that naval mines, like “The Poor,” will be with us, always.

Again, my thanks to Michael Crawford and the NHHC for the opportunity to share my thoughts and to NHHC’s Greg Bereiter for his commentary; to my colleagues George Pollitt and Norman Polmar for their technical and operational review; Greta Marlatt and Tim O’Hara for bibliographic support; and my bride Annmarie, who ignored my crankiness as the deadline drew near.

NHHC Discussant Commentary

Dr. Gregory Bereiter, Ph.D., NHHC Historian, offered his insights regarding this review of mine warfare historiography.

My comments in response to Scott’s presentation will briefly address two issues. First, I’d like to consider the challenges of researching and writing about recent operational history in general. Second, I’d like to suggest some potential avenues for future historical work on mine warfare in the U.S. Navy.

Scott’s presentation has touched on a crucial challenge for naval historians in general: how to approach the recent past. While many problems and methods are similar regardless of the time period, recent history introduces particularly challenging obstacles, from ephemeral digital sources to surviving participants with a vested interest in how their history gets written. Historians who seek to write about recent operations—especially about its more obscure aspects (like naval mine warfare)—confront challenges and dilemmas that our graduate training does not entirely prepare us to navigate.

Historians are trained to research in archives. However, most official documents on recent mine warfare operations are classified—and will remain so for the foreseeable future. Thus, anyone “outside the family” attempting to write about recent mine-warfare developments won’t be able to access the documents they need to reconstruct a given event. This forces a heavy reliance on eyewitness recollections. But historians would never rely solely on what historical actors of, say, the 17th or 18th century said they were doing. Yet, despite the fallibility of memory, oral histories are sources of insights that cannot be found in written records. Our job is to bring myriad resources together, so that we might not only reconstruct what actually happened, but also interpret the meaning of what happened in the broadest terms.

Despite these challenges, avenues for future historical work on naval mine warfare certainly exist.

Some of the most exciting recent work on mine warfare focuses on the later 19th and early 20th centuries. Two recent articles in The Journal of Military History demonstrate the promise of current research into this topic. Timothy Wolters’ examination of Confederate “electric torpedo” development in the Civil War provides a fascinating perspective on the ways in which mining technology, memory, and history were interconnected. Richard Dunley’s assessment of the late 19th-century Royal Navy demonstrates how it proactively engaged with the new technology of controlled mining, shaping this technology to suit its particular strategic and cultural requirements.

There may also be an opportunity for historians to reexamine aspects of the North Sea Mine Barrage during World War I, which was established primarily on American initiative between March and June of 1918 in an effort to restrict the movements of U-boats from the North Sea into the Atlantic.

Historians of the Cold War–era Navy should also note that one of the key aims of NATO maritime strategy during the Cold War was to prevent the exit of Warsaw Pact naval forces through the Danish Strait or the Turkish Strait in European waters, or the exit of the Soviet Pacific Fleet through La Pérouse Strait and the Korea Strait in the Pacific.

Lastly, in light of present escalating tensions with Russia and China, both of whom together are thought to possess close to 350,000 sea mines, historians of the very near future will likely need to engage in comparative historical analysis of anti-access and area-denial warfare against these two maritime competitors.

Sources:

Appendix 1 U.S. Navy Operations 1980–2010 (158)

Appendix 2 U.S. Navy Operations 1980–2010: Types of Operations

Notes

1 It was by accident that I became interested in naval mine warfare––mine countermeasures, as well as mines and mining. An Air Force brat growing up in the 1950s, I remembered World War II submarine movies, particularly enthralled by Cary Grant’s maneuvering the USS Copperfin through a defensive minefield in Operation Destination Tokyo. In 1979, I worked on a project to address the international legal regime related to the development and operation of a very long-range, accurate, stealthy, and precise remote-control, multiple-influence, submarine-launched mobile mine. My “Mines of August: An International Whodunit” appeared in the May 1985 U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings/Naval Review, 94–117. Since then my teams and I have provided research, analysis, and program support to the Navy’s mine warfare community, including producing the service’s first post–Cold War mine warfare plan in 1992—Mine Warfare Plan: Meeting the Challenges of an Uncertain World (U) (Washington, D.C.: Mine Warfare/EOD Branch [OP-363], Assistant Chief of Naval Operations for Surface Warfare [OP-03], Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 29 January 1992) Unclassified. This also was produced in a classified version.

2 Earlier in 1984, several mines were planted in Nicaraguan ports and waters, damaging several ships and generating suspicions that the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency had assisted the anti-communist insurgents, the Contras, intent on overthrowing the Sandinista government. In fact, the mining operations were carried out by CIA-hired contractors without the Contras’ knowledge. No mines were recovered, and the United States rejected the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice. Howard S. Levie, Mine Warfare at Sea (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1992), 162–63; Jude Justice Reed, “‘Damn the Torpedoes!’: International Standards Regarding the Use of Automatic Submarine Mines,” Fordham International Law Journal 8, issue 2, article 5 (1984): 286–22; and the Report of the Select Committee on Intelligence, U.S. Senate, 98th Congress Second Session, 1 January 1983 to 31 December 1984, 4–12.

The Arabian Gulf Iran/Iraq “Tanker War” 1980–1988 also witnessed the indiscriminate use of naval mines. Martin S. Navias and E. R. Hooton. Tanker Wars: The Assault on Merchant Shipping During the Iran-Iraq Conflict, 1980–1988 (London: Tauris Academic Studies, I.B. Tauris Publishers, 1996), ch. 6. See also George K. Walker, ed., “Chapter VI: The Tanker War and the Maritime Environment, The Tanker War 1980–1988—Law and Policy,” International Law Studies, Naval War College Press 74 (2000): 481–604; and Michael A. Palmer, On Course to Desert Storm: The United States Navy in the Persian Gulf (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, Contributions to Naval History No. 5, 1992), 121–34. Ronald O’Rourke reported that of the 340 types of weapons used by both sides through 1987, only ten were mines. Mines were employed in 1987 for the first time since 1984, and the first 1987 mine attack occurred near Kuwait, a day after the Iraqi missile attack on Stark (FFG-31). The victim of the mining was a Soviet-flag ship chartered by Kuwait. Even counting some of the “unknown attacks” as mine-related, however, mining accounted for only a small fraction of all attacks. The significant attention paid to the mining threat might thus be seen in part as a reflection of the psychological effect that mines can generate. “The Tanker War,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 1988; http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1988-05/tanker-war.

3 Tamara Moser Melia, “Damn the Torpedoes”: A Short History of U.S. Naval Mine Countermeasures, 1777–1991 (Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1991); http://edocs.nps.edu/dodpubs/topic/general/DamnTorpedoesWhole.pdf, 76.

4 Roy R. Manstan and Frederick J. Frese, Turtle: David Bushnell’s Revolutionary Vessel (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2010); Gregory K. Hartmann with Scott C. Truver, Weapons That Wait: Mine Warfare in the U.S. Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991); Levie, Mine Warfare at Sea; and Melia, “Damn the Torpedoes,”.

5 Scott C. Truver, “Mines and Underwater IEDs in U.S. Ports and Waterways,” Naval War College Review 61, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 106–27; CDR Michael C. Sparks, USN, “A Critical Vulnerability, A Valid Threat: U.S. Ports and Terrorist Mining,” Paper, Joint Forces Staff College, Joint Advanced Warfighting School, 13 April 2005; and Peter von Bleichert, “Port Security: The Terrorist Naval Mine/Underwater Improvised Explosive Device Threat,” dissertation, Walden University, 2015; http://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations.

6 On the Chinese threat, see my “Taking Mines Seriously: Mine Warfare in China’s Near Seas,” Naval War College Review 65, no. 2 (Spring 2012): 30–66.

7 In addition to the “Mines of August” article, see generally: Elsadig Yagoub A. Abunafeesa, “The Post-1970 Political Geography of the Red Sea Region with Special Reference to United States Interests,” dissertation, Durham University, 1985; http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7876/, 384, 394–400; David Crist, Twilight War: The Secret History of America’s Thirty-Year Conflict with Iran (New York: Penguin, 2013), “The Invisible Hand of God,” ch. 13, 235–55;

Hartmann and Truver, Weapons That Wait, 250–55; Levie, Mine Warfare at Sea,, 159–62; and Melia, “Damn the Torpedoes,” 118–19.

At my request, in June 2016, Dr. Timothy O’Hara, Research Scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses, searched the CNA library and archives for “Operation Intense Look,” which resulted in no original analyses or sources that would help the historiography, and “Operation Candid Hammer,” which turned up one citation.

8 Soviet News and Propaganda Analysis, based on Red Star (The Official Newspaper of the Soviet Defense Establishment) for the period 1–31 August 1984 (Washington, D.C.: Joint Special Operations Agency, Joint Chief of Staff, 1984), 10–11.

9 Melia, “Damn the Torpedoes,” 119.

10 Department of Defense, Conduct of the Persian Gulf War: Final Report (Washington, D.C.: 1992), 273–78; Mine Warfare/EOD Branch (OP-363), Mine Warfare Plan, 8–17; Melia, “Damn the Torpedoes,” 127–31; and Anthony Cordesman and Abraham R. Wagner, The Lessons of Modern War, Volume IV: The Gulf War (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996), ch. 10, 810–17.

11 There are other uncertainties, with some references noting a Candid Hammer exercise in November–December 1990 and others indicating operations in January–April 1991. In June 2016, Dr. O’Hara searched the Center for Naval Analyses library and archives for “Candid Hammer,” turning up only one document, an archived classified DESRON (Destroyer Squadron) 15 report, with the (unclassified) name of the document, “Exercise CANDID HAMMER File, 20 Dec 90–11 Jan 9.” Those dates match up with the discussion of a maritime patrol aircraft deployment: “1 Nov–Dec 1990: VP-4 (‘Skinny Dragons’) deployed to Diego Garcia in support of Desert Shield, and participated in exercise Candid Hammer while operating out of a remote site at Massirah, Oman.” Michael D. Roberts, Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons, Volume 2, The History of VP, VPB, VP(HL) and VP(AM) Squadrons (Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 2000), 39.

On 16 January 1991, U.S. Central Command announced the completion of the exercise/operation “CANDID HAMMER, communications techniques/mine warfare drills in central Arabian Gulf (Participants: USN, Royal Saudi, French, British, Canadian, and Australian naval forces);” https://www.facebook.com/RememberingtheGulfWar/posts/467897699934301 and http://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/us-navy-in-desert-shield-desert-storm/january-1991.html.

Also, naval analyst Caitlin Talmadge provided data specific to Candid Hammer, from 1 March to 20 April 1991. See, “Closing Time: Assessing the Iranian Threat to the Strait of Hormuz,” International Security 33, no. 1 (Summer 2008): 94–96.

During June 2016, I “pinged” on the U.S. Navy and foreign navy mine warfare community via an informal Internet mine warfare information service maintained by George Pollitt, a mine warfare expert at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. He emailed the question—“Does anyone recall an Operation Candid Hammer in 1990–91?”— to several hundred recipients that included Gulf War commanders of the mine warfare group, commanders and crews of the MCM vessels, and AMCM helicopter pilots: “No.” It remains an enigma.

12 Edward J. Marolda, “The U.S. Navy in the Cold War Era, 1945–1991” (based on the chapter, “Cold War to Violent Peace,” in W. J. Holland Jr., ed., The Navy. Washington, DC: Naval Historical Foundation, 2000.), http://usnavymuseum.org/pdf/Activity_16_background.pdf, 28. See also, Edward J. Marolda and Robert J. Schneller Jr., Shield and Sword: The United States Navy and the Persian Gulf War. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1998, 68, 118, 122, 141–42, 148–49, 181, 192, 205, 212, 223–26, 231, 233, 247–51, 255–59, 277, 282, 321–25, and 442. There is no mention of Candid Hammer in a list of related operations at page 507.

13 Talmadge, “Closing Time,” , 95.

14 Boynton, “Operations to Defeat Iranian Maritime Trade Interdiction,” paper, Naval War College, 4 May 2009.

Mine warfare expert George Pollitt, who was in-theater during “sweep” ops, recalls, “The MCM operations started in early February with AMCM, USS Avenger, three MSOs, and four Royal Navy Ton Class sweepers and continued through the end of June 1991. By my rough calculations, 650 square nautical miles were cleared during that period. The USN and RN forces operated alone until the WEU came in. Then all operated until 30 June. (The WEU came

back to port on 20 July according to Marolda, but the USN was still operating, and I know that AMCM cleared nine mines using the Q-14 during the last two weeks they were out there.) Altogether I counted 25 ships and six AMCM helicopters clearing. The overall clearance rate was 0.2 square nautical miles per MCM asset day. It was true that some of the mines were cleared quickly by the French and Belgians after they knew the mine positions (they went straight down the mine-lines, as defined by the Iraqi charts), but that was only part of their assignment, and they were not assigned the entire area.” Email exchange, 9 August 2016.

15 Mine Warfare/EOD Branch (OP-363), Mine Warfare Plan, 21–22.

16 Breemer, “Intense Look: U.S. Minehunting Experience in the Red Sea,” Navy International 90, no. 8 (August 1985): 478–82.

17 For example, writing in 2013, David Crist, Twilight War,, ch. 13, 600 n3, states, “By far the most comprehensive account of this operation” was the “Mines of August” article.

18 Edward J. Marolda, ed. Operation End Sweep: A History of Minesweeping Operations in North Vietnam (Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center, 1993).

19 “Coastal defense” or “offense” should not be discounted. As “regime change” in Libya was being carried out in the spring 2011, forces loyal to Gaddafi reportedly laid mines off the coast of Misurata. A NATO spokesperson noted three sea mines were discovered two miles off shore and destroyed, but there were fears that others remained as yet unfound and posed a threat, in what officials said was a clear breach of international law. VADM Rinaldo Veri of the Italian navy said the mining of a civilian port was “clearly designed to disrupt the lawful flow of humanitarian aid to the innocent civilian people of Libya,” calling it another “deliberate violation” of Security Council resolutions. Rob Crilly, “NATO Warships Clear Misurata of Sea Mines as Gaddafi Remains Defiant,” The Telegraph, 30 April 2011; http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/libya/8485650/Nato-warships-clear-Misurata-of-sea-mines-as-Gaddafi-remains-defiant.html.

20 Lambert, “The Naval War,” in John Pimlott and Stephen Badsey, eds., The Gulf War Assessed (London: Arms and Armour, 1992), 125–46.

21 While Michael Palmer’s On Course to Desert Storm provides valuable insight into the Navy’s long history in the gulf, particularly the Tanker War (122–46), he nowhere gives mention of “The Mines of August” and leaves the history of Desert Shield/Desert Storm to others.

22 See note 9.

23 Melia, “Damn the Torpedoes”,79.

24 Scott C. Truver, “Wanted: U.S. Navy Mine Warfare Champion,” Naval War College Review 68, no. 2 (Spring 2015): 116ff.

25 Email exchange, 9 August 2016.

26 CDR David Bruhn, USN (ret) published two books on MCM vessels in 2007 and 2009: Wooden Ships and Iron Men, The U.S. Navy’s Ocean Minesweepers, 1953–1994 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2007) and Wooden Ships and Iron Men, Volume II, The U.S. Navy’s Coastal and Motor Minesweepers, 1941–1953 (Westminster, MD: Heritage Books, 2009).

Other books seek to advocate for a more robust mine warfare capability, for example: Oceans Studies Board, Oceanography and Mine Warfare (Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy Press, 2000): and Naval Studies Board, Naval Mine Warfare: Operational and Technical Challenges for Naval Forces (Washington, DC: National Research Council, National Academy Press, 2001).

27 RADM Paul Ryan, USN, and Scott C. Truver, “U.S. Navy Mine Warfare Vision . . . Programs . . . Operations: Key to Sea Power in the 21st Century,” Naval Forces 90, no. 3 (2003): 28–32.

28 “Sea Tiger Commandos Sink SLN Supply Ship in Trinco Harbour,” TamilNet, 9 May 2008; https://www.tamilnet.com/art.html?catid=13&artid=25590.

[END]