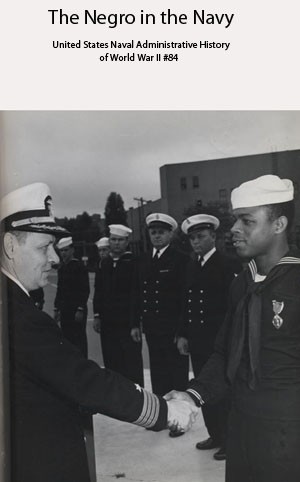

Historical Section. Bureau of Naval Personnel. "The Negro in the Navy." (Washington, DC: 1947). [This manuscript, identified as United States Naval Administrative History of World War II #84, is located in the Navy Department Library's Rare Book Room.]

The Navy Department Library

The Negro in the Navy

United States Naval Administrative History of World War II #84

The Negro in the Navy

First Draft Narrative

Prepared by the Historical Section

Bureau of Naval Personnel

1947

Table of Contents

| Page | ||

| Part I | ||

| The Negro in the Navy in World War II | 1 | |

| Sources | 100 | |

| Appendix: List of Documents | 103 | |

| Part 2 | ||

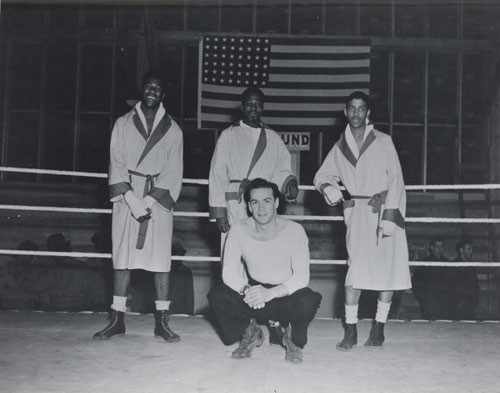

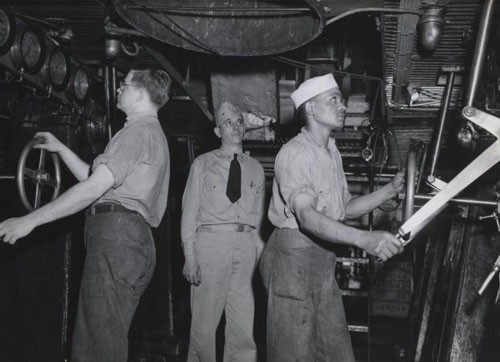

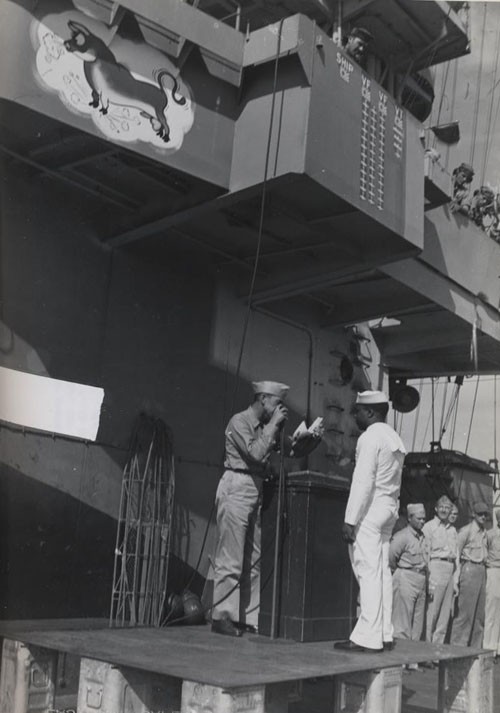

| Photographic Appendix * | ||

* Photographs have been incorporated in the narrative.

No photographs in online project.

THE NEGRO IN THE NAVY

| Page | |||

| I | The Basic Decision | 1 | |

| a. | Before 1941 | 1 | |

| b. | The Decision | 3 | |

| c. | Selective Service: An expanded program. | 9 | |

| d. | Negroes in the Women's Reserve | 15 | |

| II | Special Provisions for Administration | 18 | |

| a. | In the Bureau | 18 | |

| b. | Outside the Bureau | 22 | |

| III | Distribution | 27 | |

| a. | Theories governing distribution. | 27 | |

| b. | Negro competence | 28 | |

| 1. Scores for all recruits | 28 | ||

| 2. Petty officers | 35 | ||

| c. | "Sea Duty" for Negroes | 40 | |

| 1. The Fleet | 40 | ||

| 2. Naval Districts | 45 | ||

| 3. Bases outside the Continental United States | 46 | ||

| 4. The Commissary Branch | 49 | ||

| d. | Shore Duty in the United States | 51 | |

| 1. Balance in distribution | 51 | ||

| 2. Proper use of training | 53 | ||

| 3. Use only in military billets | 53 | ||

| IV | Producing the men | 54 | |

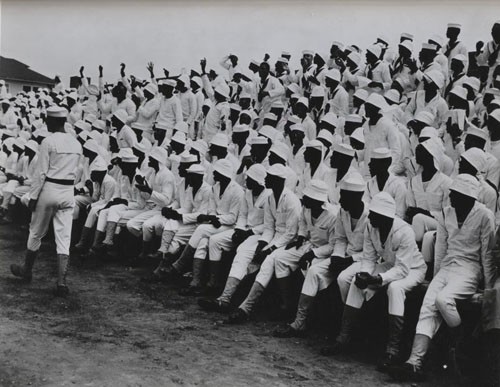

| a. | Procurement | 54 | |

| b. | Training | 56 | |

| 1. Segregation | 56 | ||

| 2. Scope | 59 | ||

| V | On the Job | 64 | |

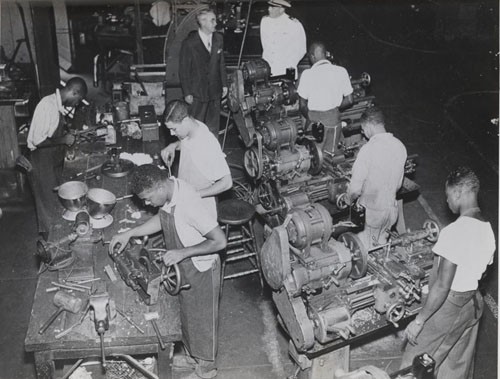

| a. | Opportunities for skill | 65 | |

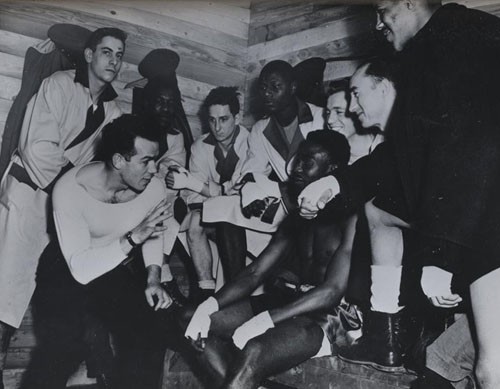

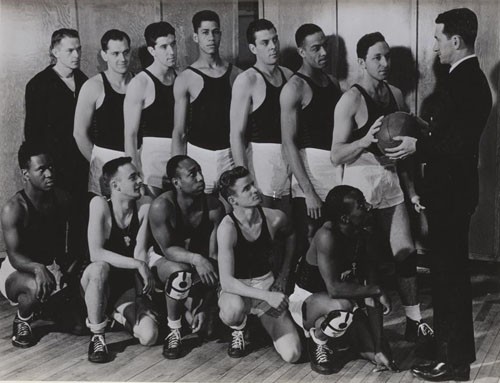

| b. | Living conditions and recreation | 70 | |

| c. | Discipline: In general | 73 | |

| d. | Discipline: "Incidents" | 75 | |

| 1. NAD, St. Juliens Creek, Virginia | 75 | ||

| 2. The 80th Construction Battalion | 77 | ||

| 3. Shoemaker, California | 79 | ||

| VI | An Established Program: 1944-1945 | 81 | |

| a. | Organization | 81 | |

| b. | Officers | 83 | |

| c. | Enlisted Procurement | 85 | |

| d. | Enlisted Training | 88 | |

| e. | Enlisted Distribution | 90 | |

| f. | On the Job | 94 | |

| g. | Women's Reserve | 98 | |

I. THE BASIC DECISION

Before 1941

There have been Negroes in the United States Navy since the early years of the Republic, but their numbers have always been small. Camp Robert Smalls, the first Negro recruit camp at the Great Lakes training station in World War II, was named for a Negro who rendered distinguished service to the Federal Navy in the Civil War.

Older Navy men today recall the service of Negroes aboard the larger combatant vessels from the turn of the century through the first World War. They served not only in the messman branch, but also held various skilled ratings as artificers. There is some confusion in the evidence as to whether in this period Negroes were enlisted for general service as well as for the messman branch, or only for the latter. Testimony of men who knew the Navy through those years is at variance; some enlistment records have been seen which indicate direct enlistment for general service, but these may always have been departures from a general rule.

In any case, when the size of the Navy was curtailed in consequence of the disarmament movement following World War I, enlistment of Negroes seems to have been discontinued by BuNav. Recruiting of Negroes as messmen may have been kept open formally, but at least in practice only Filipinos were recruited for this branch from about 1919-1922 until December, 1932. About December 1932, active recruiting of Negroes for the messman branch began and this was the only branch in which Negroes could enlist until recruiting for general service was opened to them as of June 1, 1942. When World War II opened there were on active duty in the Navy, in other than the messman branch, six rated Negroes of the regular Navy, 23 rated men who had returned from retirement to service in the regular Navy and 14 rated men of the Fleet Reserve.

--1--

All of these, presumably, were men who had been serving at the time when the Navy was cut after the first World War; several of them were Chief Petty Officers.

--2--

The Decision

The Selective Service and Training Act of 1940, provided in the preamble that:

(b) The Congress further declares that in a free society the obligations and privileges of military training and service should be shared generally in accordance with a fair and just system of selective compulsory military training and service.

The third proviso of Section 3(a) gave practical application to this declared policy:

...any person, regardless of race or color, between the ages of eighteen and forty- five, shall be afforded an opportunity to volunteer for induction into the land and naval forces of the United States for the training and service prescribed in subsection (b)...

And the first proviso of Section 4(a) stated the obligation of the Services towards all men taken into service:

... in the selection and training of men under this Act, and in the interpretation and execution of the provisions of this Act, there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race or color.

July 2, 1941, SecNav created a committee, consisting of a Captain and Commander in the Navy, a Colonel in the Marine Corps, and a Special Assistant to Assistant SecNav, "for the purpose of investigating and reporting to SecNav the extent to which (sic) the enlisted personnel of the Navy and Marine Corps is representative of all United States Citizens, and in case there should be any evidence of discrimination because of race, creed, color or national origin, to suggest corrections." Subsequently, "by oral instructions," the committee decided to limit its inquiry "to the existing relationship between the United States Navy, United States Marine Corps and the Negro race."

This committee held three meetings for discussion of the issues under investigation. It reported that prior to 1922 Negroes were recruited for

--3--

general service, that experience showed that this open recruiting yielded only 2.1 percent of Negroes in the Navy, and that few of these qualified for advancement except for ratings where little or no military command must be exercised. There was no report, however, of the extent to which Negro recruitment was pushed or the degree to which there was planning for integration of Negroes into the Service.

A majority of the committee felt that

...the enlistment of Negroes (other than as mess attendants) leads to disruptive and undermining conditions.

and reported to SecNav on December 24, 1941 its conclusion that

Within the limitations of the characteristics of members of certain races, the enlisted personnel of the naval establishment is representative of all the citizens of the United States. Therefore, no corrective measures are necessary.

A dissenting opinion, filed December 31, 1941, was expressed by the Special Assistant to Assistant SecNav. He believed that it should be practically possible to find limited service billets for Negroes, and that the damage done to national morale and harmony by denying them a proportional part in the war effort outweighed what added attention must be given such a program. He thought that

...a limited number of qualified Negroes could be enlisted for duty on some types of patrol or other small vessel assigned to a particular yard or station.

An experiment of this sort, he felt,

...might prove to be of considerable value in case the Navy is later directed to accept enlistment from the Selective Service Rolls.

Pearl Harbor provided the impetus for the next development. December 9, 194l, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People wired SecNav, asking whether, in view of the intensive recruiting campaign then under way, the Navy would accept colored recruits for other than the messman's branch. BuNav replied that there had been no change in policy and that none was contemplated.

--4--

The NAACP wrote the President in protest of this decision, December 17, 1941. The President referred the protest "for reply" to the chairman of the Executive-created Fair Employment Practices Committee. On December 31, 1941, the chairman informed the President that he had already conferred with the Navy, at the latter's request, on the NAACP telegram of December 9. He advised the President, for himself and his committee, that even following a segregation policy the Navy ought to be able to use Negroes in the Caribbean or on harbor craft. He pointed out, however, that he had discussed the Negro question with the Navy only at its request, that under its Executive Order the FEPC had no jurisdiction of race questions in the armed services, that he could thus reply to the NAACP only on a personal basis along the lines indicated. He suggested, therefore, that the President might wish to consider the matter further.

January 9, 1942, the President referred this letter to SecNav, requesting consideration, and commenting,

I think that with all the Navy activities, BuNav might invent something that colored enlistees could do in addition to the rating of messman.

January 16, 1942 SecNav asked the General Board to submit a plan for taking 5000 Negroes for billets other than in the messman branch, requesting further that the Board state their ideas as to the type of duty, assignments, etc., "which will permit the Navy to best utilize the services of these men." The General Board reported on February 3, 1942. Analyzing the complements of various types of ships, the Board noted that there were few non-rated billets on patrol vessels, and that there were then no Negro officers and few Negro petty officers to fill the other posts. Mingling Negroes with whites in the relatively large number of non-rated billets on larger ships would inevitably promote race friction and lowered efficiency, the Board held.

--5--

The General Board report stated that if restriction of Negroes to the messman branch was discrimination

It is but part and parcel of similar discrimination throughout the United States, not only against the Negro, but in the Pacific States and in Hawaii against citizens of Asiatic descent.

Board went on:

The reasons for discrimination in the United States are rather generally that: (a) the white man will not accept the negro in a position of authority over him; (b) the white man considers that he is of superior race and will not admit the negro as an equal; and (c) the white race refuses to admit the negro to intimate family relationships leading to marriage. These concepts may not be truly democratic, but it is doubtful if the most ardent lovers of democracy will dispute them, particularly in regard to inter-marriage.

The General Board noted that Negroes were permitted some participation in combat, since messmen were given stations during battle. In summary, the Board recommended that

Members of the colored race be accepted for enlistment only in the messman branch

but that if this proved not feasible, they be enlisted for general service.

On February 5, 1942, SecNav transmitted the General Board's report to the President, remarking that

The only special service that I can think of where segregation could be possible would be in the Marine Corps.

The President replied in a memorandum to SecNav stating that he did not believe the only choice lay between messman duty for Negroes and their acceptance into all duties in the Naval service. He felt that

...to go the whole way at one fell swoop would seriously impair the general average efficiency of the Navy.

Nevertheless he believed that there were some jobs other than messman to which Negroes could be properly assigned. He asked that the recommendations of the General Board be returned to that Board "for further study and report."

--6--

On February 14, 1942, SecNav asked the General Board to reconsider the question in the light of the President's comments. Accordingly the General Board on February 18, 1942, asked BuNav to furnish a list of stations or assignments for Negroes in other than the messman branch "and wherever the assignment of these men would not 'inject into the whole personnel of the Navy the race question.'"

The General Board commented:

It is unwise and inadvisable to repeat or further emphasize the undesirability of the recruitment of men of the colored race.

Quoting this last comment, BuNav on February 20 asked CNO and BuAer for recommendations.

On February 25, CNO replied, "that men of the colored race, other than those for the messman branch, be not assigned to ships or shore stations."

If, however, men of the colored race are to be enlisted in the Navy in ratings other than in the messman branch, CNO recommends their enlistment in the Reserve, and their assignment to (1) Construction Battalions under the Bureau of Yards and Docks; (2) Shore Stations, for work around docks or general labor such as now performed by enlisted men, or could be so performed in places like Naval Supply Depots, Navy Yards, Ordnance Stations, Training Stations, Experimental Stations. Section Bases, Air Stations, etc., - in general - the Naval Shore Establishment; and (3) Yard Craft. Of the above listed alternatives, the Chief of Naval Operations would prefer recourse to (1) and (2) only. Alternative (3) has been included in case it is necessary to assign billets afloat.

Cominch noted his concurrence.

On March 20, 1942, the General Board, reported to SecNav that "the organization of ... colored units" could be effected with least disadvantage in the following types of activity, if so ordered: service units throughout the naval establishment (including shore activities of the Marine Corps and Coast Guard); yard craft and other small craft employed in Naval District local defense forces; shore based units for other parts of District local defense forces;

--7--

selected Coast Guard cutters and small details for Coast Guard Captains of the Port; construction battalions; composite Marine battalions. Segregation was an essential principle of administration, and hence Negroes could not be used in any general service billets in the Fleet.

The General Board then restated its views:

The General Board fully recognizes, and appreciates the social and economic problems involved, and has striven to reconcile these requirements with what it feels must be paramount in any consideration, namely the maintenance at the highest level of the fighting efficiency of the Navy ... that wide latitude be granted the several administrative authorities as to rate of enlistment, method of recruiting, training and assignment to duty and that progressive experience determine the total number to be enlisted.

SecNav transmitted the second report on March 7. On March 31, 1942 the President expressed his interest in the report but noted disagreement with the statement that

... wide latitude be given the several administrative authorities as to rate of enlistment, method of recruiting, training and. assignment to duty and total number to be enlisted.

This matter, he said, "should be determined by you and by me!" After conference with SecNav the President ordered that the necessary steps be taken to initiate a Negro program along the suggested lines.

Out of this immediate background came the Navy's announcement, April 7, 1942, that beginning June 1, 1942, Negroes might enlist for general service as well as in the messman branch. The first plan set a recruiting quota of 277 per week; it was contemplated that the first year of recruiting would yield a maximum of about 14,000 Negroes for general service.

--8--

Selective Service: an Expanded Program

At the end of 1942 and in the early months of 1943 pressure converged on the Navy from several sources - the Army, the War Manpower Commission and the White House particularly - resulting in a great expansion of the Negro program. On June 30, 1942, there were 5026 Negroes in the regular Navy (almost all of them mess attendants); this figure was about two percent of the total enlisted male personnel of the Navy, and about two and one half percent of the male regulars. As of February 1, 1943, there were 26,909 Negroes in the Navy. Over two-thirds of these were messmen (18,227); 6,662 were General Service; 2,020 were Seabees. This represented about eight percent of the regular male enlisted male personnel, and about two percent, again, of the total enlisted male personnel as of that date.

The Negro program climbed rapidly in numbers. By December 31, 1943 there were 101,573 Negroes on active duty in various rates, 37,981 of whom were Stewards Mates (about 36%). June 30, 1944 saw a total of 142,306, of whom 48,524 were Steward's Mates (about 33%). The figure for December 31, 1944 indicated the leveling off of growth, with a total of 153,199, including 52,994 Steward's Mates (about 34%). As the war reached its climax, on June 30, 1945, the Navy counted on active duty 165,500 colored enlisted personnel. 75,500 of these were Steward's Mates (about 45%). As of June 30, 1945 about 123,000 colored personnel had served or were serving overseas.*

The Joint Chiefs of Staff in the fall of 1942 requested that a study be made of personnel needs of the Services in 1944 and beyond, and also directed

___________

*See Yearbook of Naval Personnel Statistics, 1944, Table 8 ("Negro Ratings: Number of Negroes on Active Duty by Rates," (1943-1944), and table 27 ("Duty Assignments of Negro Enlisted Men Rated and non-Rated Negroes on Board Various Activities, 31 December 1944"). The 1945 figure is from the files of the special programs unit, Planning and Control Activity.

--9--

that consultation be had with the Chairman of the War Manpower Commission to establish a proper balance between manpower resources and requirements. On October 19, 1942, the Chief of Naval Personnel noting that these studies were under way, wrote the Commandants of the Coast Guard and Marine Corps that

It is anticipated that the employment of Negroes will be a matter of discussion in this connection.

Accordingly, he requested their views regarding "the maximum number" of Negroes who might be employed in their respective Services. The Coast Guard replied that it could use 2000 colored men in the Messman Branch, 390 on ships in branches other than the Messmen's and 1610 in miscellaneous general duty. The Marine Corps replied that it had planned to use 1041 in "composite battalions", in the fiscal year 1943 and a like number in 1944. Otherwise, without giving estimates the Commandant believed that

In the event the decision is that the Marine Corps must take Negroes, a small number could be used as (a) Messmen at larger Marine Corps posts within the United States, (b) Labor Battalions. The Primary duties of these battalions will be the unloading of ships in the theatre of operations.

The Commandant expressed the opinion that if the Corps were required to take more Negroes than already planned, increases in its total size would be necessary, since previous estimates of its total personnel needs had been made on the assumption that all men therein would be of the type now being enlisted.

Much broader considerations and conflicts over manpower policy than those involved immediately in the Negro program led, on December 5, 1942, to the President's decision that, except for the existing backlog of applications for enlistment, the Navy must henceforth obtain all of its draft age recruits through the Selective Service system. This new procedure went into full operation by the first week of February, 1943.

--10--

Meanwhile, at meetings on January 20 and 27, 1943, the War Manpower Commission (including representatives of the War and Navy Departments) discussed the induction of Negroes in numbers proportionate to their number in the population. The Commission already had before it a recommendation of its staff that, beginning April 1, 1943, local draft boards be instructed to fill their quotas by taking registrants according to their order numbers without regard to color. Previously, with the Army alone taking colored registrants, separate calls had been issued for whites and Negroes, and local boards passed over Negro registrants in order to fill white calls. The Selective Service System had, in consequence, a backlog of several hundred thousand colored registrants who, according to their order numbers, should have been called to service, but had been passed over. The Commission now asked the Army and Navy representatives to report to it the reactions of the Departments to the proposals to end special calls.

The chairman of the War Manpower Commission wrote SecNav, February 17, 1943 that

The practice of placing separate calls for white and colored registrants is a position which is not tenable, and it is now necessary to begin delivering men in accordance with their order number without regard to race or color.

Negroes formed ten percent of the country's population, but so far were less than six percent of the armed forces, and almost all of these were in the Army, the Chairman continued. The Selective Service Act imposed a ban on racial discrimination, he pointed out, and apart from this there were serious social implications in the existing state of affairs:

The low percentage of Negroes in the Army and in the Navy has resulted in a higher percentage of Negroes in the civilian population. This situation is made more serious because of the geographical concentration of Negroes and because nearly all of the men involved, Negro and white, have been single ... This condition has been the cause of continuous and mounting criticism. It possesses grave

--11--

implications, should the issue be taken into the courts, especially by a white registrant. The probability of this action increases as the single white registrants disappear and husbands and fathers become the current white inductees, while single negro registrants who are physically fit remain uninducted.

After the Navy came under Selective Service, it was the Bureau's expectation that the old quota of about 1200 general service end 1500 messmen could be continued. But in a memorandum of February 22, 1943 to SecNav the President suggested that a check of all present white and colored enlisted jobs in the Navy would show places for further use of colored men, including "shore duty of all kinds, together with the handling of many kinds of yard craft." He emphasized that there would be much criticism, if Negroes were not used ultimately in proportion to their numbers in the population.

On February 26, 1943, the Bureau recommended an increase from the existing total quota of 2700 per month to 5000 in April and 7350 for each of the remaining months of that year; mess attendants were to be increased from 1500 to 2600 per month, 4750 would be trained for general service, and 1000 would go to the SeaBees. On February 26, 1943, SecNav wrote the War Manpower Commission that the Navy, Coast Guard and Marine Corps would absorb up to ten percent of Negroes in their personnel, but that separate white and colored "calls" must be continued for the time being to permit of adjusting the increasing flow of colored men to the expansion of needed facilities. On March 2, the Commission expressed its gratification at the Navy's statement, agreed to temporary continuation of separate calls, and requested figures as to the monthly calls planned by the Navy and its related services.

SecNav's reply to this last request, on March 13, 1943, made clear that the Navy interpreted its obligation to make up to ten percent colored as meaning

--12--

up to ten percent of the total increase of its personnel between February, 1943 and January 1, 1944. The Commission found this inequitable, in a reply, March 23, 1943, requesting the induction of approximately 125,000 Negroes by January 1,1944, in contrast to the Navy's proposed 80,350. The Commission's chairman stated that this figure "will enable us to plan for the initiation of general calls without specification as to the respective number of Negro and White registrants." The Navy finally struck a compromise with the Commission to the extent that it was agreed that Negroes would be taken at the rate of about 12,000 per month for the rest of 1943 for a total of 107,650 by December 31, 1943, with enough expansion of the early months' quotas in 1944 to make up the 125,000 figure demanded by the Commission.

The President had indicated that he desired a fairly wide dispersion of the Negroes throughout the shore establishment, including their assignment to yard craft and other small vessels. On February 25, 1943, close on the heels of the President's order that a proportionate number of colored personnel be used, SecNav submitted an outline plan prepared by the Bureau:

(a) Increase the all-colored construction battalions from two to five; (b) Provide for 24 new construction battalions, all non-rated personnel to be colored; (c) Increase the numbers of colored crews in the harbor craft and local defense forces; (d) Create service companies at all ports of embarkation; (e) Increase the number of colored cooks and bakers in the commissary branch for shore establishments within the United States; (f) Increase the percentage of colored personnel at section bases, ammunition depots, net depots and naval air stations on this continent.

This outline was approved. SecNav on April 14, 1943, sent the President a further outline of policy:

Salient features of the Navy program are: (a) There will be no mixing of crews on large combatant ships other than for personnel

--13--

of the Stewards Mates branch. (b) No Negro personnel will be assigned initially to the Hospital Corps. (c) Negro personnel will be used to fill complements of all local defense and district craft. (d) Negro personnel assigned to the SeaBees will be for special all-Negro stevedore battalions and, in addition, be assigned to construction battalions with white personnel. (e) Negroes will be used at all shore stations, both inside and outside the continental limits of the United States, in varying percentages, averaging about 50% of the non-rated personnel at these stations.

This in fact stated some major features of the program as it grew for two years. Some points, as the use of Negroes at bases outside as well as within the United States, did not begin to develop fully until the end of that period. The President likewise approved the April 14 memorandum.

By the end of the second year of the program, it was clear that the ultimate total of Negroes in the Navy of World War II would be nearer five than ten percent. The two principal factors in the situation were (1) that the Navy would not use Negroes in the Fleet, except in the Stewards Branch and (2) that a half to two thirds of the colored men were qualified only for unskilled work, of which the Navy, by the nature of its technology, had not enough to go around. By the spring of 1944, however, the Bureau was prepared to ask the War Manpower Commission for a formal cut in the allocation of colored men to the Navy, to reflect the realities of the situation.

--14--

Negroes in the Women's Reserve

When the original legislation for the Reserve was being considered in hearings before the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, May 19, 1942, Negro women's organizations urged the inclusion in the bill of a stipulation that

in the selection, appointment, training and classification of women under this act and in the interpretation and execution of the provisions of this Act, no distinction shall be made on the ground of race or color.

It was noted that a similar provision had been proposed and rejected in connection with the legislation creating the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. The proposal was received by the committee, but nothing further was heard of the suggestion. There was, on the other hand, nothing in the terms of the Women's Reserve legislation as passed to exclude Negro women from the organization.

When recruitment for the Women's Reserve began, in the summer of 1942, several score of requests to enlist were received at the Bureau from Negro women but none were accepted. There is no evidence of White House intervention on the issue. March 9, 1943, a White House memorandum for the President passed on a protest of the Greater New York Federation of Churches against exclusion of Negroes women from the Marine Corps Women's Reserve. The memorandum was returned with an unsigned notation: "Take this up with the Secy of the Navy - Strictly speaking the woman is dead right."

By early 1943, however, there was enough pressure from both white and Negro organizations to require an examination of the issue. Thus in a letter of December 30, 1942, to the Public Affairs Committee of the National Board of the YWCA the Chief of Bureau explained that

At this time the Navy does not have any substantial body of Negro men available or qualified for general service at sea. There is no occasion to replace Negro enlisted Personnel by Negro women enlisted in the Women's Reserve.

--15--

In the spring of 1943 the office of the Women's Reserve, pressed for serious consideration of the recruiting of Negro women. A Women's Reserve officer was added to Planning and Control's special programs unit for the purpose of surveying opportunities for employing colored women and laying basic plans. On May 25, 1943, various memoranda sketching plans were submitted to the Chief of Bureau.

In these memoranda the suggestion was made that Negro women be recruited. Procurement would be through the ONOP's, as for white women, with assistance rendered by the Recruiting organization. Standards of selection would be the same as for whites and a top figure of 5000 would be set for the first year, roughly approximately a 10% rule. Training would be segregated and Negro colleges might be used. Instruction would be the same as for whites, and would be conducted, by Specialists (T), as soon as they could be obtained. Twenty-five colored officer candidates would be selected to begin with, to be sent to the Women's Reserve officers indoctrination school at Smith College, thereafter to perform administrative duties at the colored training schools; other officer candidates might later be selected as the need proved itself. At the outset the rates open include Yeoman, Storekeeper, Ship's Cook, Baker, Hospital Apprentice, and Specialists (S), (T), and (U). The colored Waves would be detailed in units suitable for separate housing, and to activities where Negro seamen were detailed and to the larger Naval Air Stations. Messes as well as quarters would be segregated on the job: the memoranda did not specify regarding segregation at work.

--16--

The Director of the Women's Reserve accepted these plans as a basis for discussion, but she was deeply concerned lest the great bulk of the Negroes brought in under any program likely to be adopted would be detailed to the type of work which Negro opinion resented as menial. The first annual report of the Women's Reserve stated:

The Director (of the Women's Reserve) is prepared to recommend admission without discrimination, but is well aware of the practical difficulty involved in implementing such a recommendation.

In September, 1943, a conference of District Directors of the Women's Reserve, recommended:

that the inclusion of Negro women be deferred as long as possible, and that when the program becomes effective, the plan be as similar to that for men as possible.

--17--

II. SPECIAL PROVISIONS FOR ADMINISTRATION

In the Bureau

Special provision for handling the problem of Negroes in the Navy began with a directive from AsstSecNav to the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation and the Director of the Office of Public Relations, January 16, 1942, instructing that all incoming questions regarding the position of Negroes in the Navy be referred to him. The directive stated that this step was taken because of the obviously delicate nature of the issues.

Noting that a critical point had been passed with the announcement of the decision to enlist Negroes for general service, AsstSecNav cancelled his former directive, by letter of May 20, 1942. On May 26, 1942, a memorandum from the assistant Chief of Bureau to the heads of all divisions of BuPers designated a Lieutenant Commander of the Naval Reserve to coordinate all activities in connection with the enlisting and training of Negroes in the Navy and to handle all correspondence regarding the subject. This Lieutenant Commander shortly thereafter also assumed the job of Bureau Public Relations Officer, and consequently was able to devote only a part of his time to a concern with Negro activities. For nearly a year the initiative for broad planning of the Negro program lay in his hands.

In the summer of 1942 the Bureau was under reorganization, according to the blueprints of a firm of management advisors. The blueprints included a Planning and Control Division, one of whose primary functions was to overcome the inertia with which any large organization meets a new and strange problem. The foresight of the management advisors went further, to the point of visualizing in the Planning and Control Division a "special programs" unit. Its job would be to take the initiative in comprehensive planning for a new program and to coordinate the varied activities of the operating divisions as they came to bear on the program.

--18--

The need was as the management engineers foresaw, and the results of their planning were good, so far as the blueprint was implemented. But progress was unfortunately slow and the means devoted to the problem never adequate.

Setting up Planning and Control took a long time. The Negro problem was one of the knottier puzzles of an expanding Navy, but it was a minor problem in the total picture. It is not surprising, therefore, that the establishment of a special unit was not pressed and that the unit was not functioning until the fall of 1943.

In June, 1943, following SecNav's intimation of concern over inadequate provision for Negro recreation at various activities, Planning and Control caused a conference of District Welfare-Recreation Officers to be called. These men brought up such a variety of problems as to point up the need for a focus of advice and assistance in the Bureau.

In a memorandum to the Chief, June 29, 1943, the Director of Planning and Control recommended that "A captain, carefully selected for his sympathetic understanding of the Negro problem as much as his naval experience, should be detailed as Special Assistant to the Chief of Naval Personnel" to administer the Negro program. It was emphasized that this administrator should be given a highly competent staff, some of them assigned to the Operating Divisions of the Bureau, so that his recommended policies and procedures might after approval be carried out "uniformly and in time."

The recommendation was sound in urging that the problem be given the amount of specialized attention which its complexities demanded. The approach taken was open to two objections, however.

First, the suggestion was not that the special unit be a part of Planning and Control, but that it have an independent status somewhat similar to that of the Office of the Women's Reserve. The management advisor to the Chief of Bureau was opposed to separate status for a Negro program. On reconsideration, Planning and Control withdrew this aspect of its recommendation, and steps were taken to order in officers deemed specially qualified to form a unit within the Division.

--19--

A second objection to the memorandum of June 29, 1943, was its concentration upon handling the Negro program in the Bureau. This was a natural emphasis for a period in which the prime issue had been the scale on which Negroes could be taken in and the uses to which they would be put. These were questions which had to be settled at the center. But the time was close when emphasis must shift to the field.

About the end of August, 1943, the recommendation was made that the special unit should consist of not less than one commander, four lieutenant commanders and two lieutenants. The senior officer would be primarily concerned with the overseeing of the whole program from the vantage point of the Bureau. The two lieutenants would be his leg men to keep a firm check on the progress of programs in the day-to-day administration of the operating divisions; at least for a transitional period, the actual administration of the critical job of distribution would be taken over from the Enlisted Division. Each of the lieutenant commanders would ride circuit between the Bureau and one of four areas into which the United States would be divided, according to the distribution of Negro personnel. Their task would be one of continuously interpreting Bureau policy to the field and field problems to the Bureau. They would come to local activities as advisors armed with the best forethought and experience which the Bureau was able to gather for the assistance of the activity CO's whose traditional

--20--

autonomy would not be invaded. At that time the unit consisted of a lieutenant commander and lieutenant reporting to the Control Officer for the Planning and Control Division. Both officers had had about a year's experience in Naval training school for Negroes.

--21--

Outside the Bureau

The peculiar difficulties of the Negro program called for some adjustments in relations between the Bureau and the activities and in personnel administration in the field. Following sound principles, these efforts took the form of tightened central control over the application of one crucial policy and attempts to strengthen local personnel and then leave them to work out their own problems of adjustment.

The issue of central importance was that of distribution (discussed in detail in Part III.) For the kinds of billets to which Negroes would be assigned would determine the numbers readily to be taken, types of training and the state of morale. Control of distribution was, therefore, kept carefully in the Bureau, and within the Bureau it was watched closely by the special unit of Planning and Control. The plan for an expanded special unit had contemplated that, until the application of basic policies was firmly set, the actual detailing would be done by Planning and Control. Though the plan was not adopted and the personnel available did not permit doing this, Planning and Control kept in close touch with the Enlisted Division on all detailing policy. Planning and Control settled two important issues first, that distribution should follow the general lines of surveys made in the field by its representatives; and second, that special pains were to be taken that northern Negroes be not detailed to the South, if possible. Applied to the field, those Bureau policies meant that Negro drafts were not sent to the Districts for further distribution according to the discretion of the Commandant, as in the case of whites. By conference between Planning and Control representatives and the CO's and personnel officers in the various commands and activities, definite figures were reached as to the number of Negroes to be included in station complements and the types of jobs they would fill. Negroes were detailed accordingly, and

--22--

the Districts were under instructions not to change the detail without consultation with the Bureau. This was fortified by the injunction to use the men in the ratings for which they had been trained. As Bureau representatives travelled among the activities to the extent that their limited numbers permitted, they kept constant check on compliance with these directives. Similar Bureau control of distribution was exercised regarding the Women's Reserve, because like need was felt to control the execution of policy in a new field.

In the period in which the general Negro recruiting campaign was on, between June 1, 1942 and February, 1943, the Bureau left promotional activities almost entirely up to the Negro recruiting officers who had been carefully selected. This policy was intended to facilitate the personal contact approach that was the staple of the recruiting stations.

The lesson was early learned that what must count in initial selection was imagination, firmness and capacity to deal with people, rather than any specialized background of "knowing" Negroes. An officer with a record of highly successfully training of Negro SeaBees warned against this theory:

We no longer follow the precept that southern officers exclusively should be selected for colored battalions. A man may be from the north, south, east or west. If his attitude is to do the best possible job he knows how, regardless of what the color of his personnel is, that is the man we want as an officer for our colored SeaBees. We have learned to steer clear of the "I'm from the South - I know how to handle 'em" variety. It follows with reference to white personnel, that deeply accented southern whites are not generally suited for Negro battalions.

The problem then was one of training. In the summer of 1943 the experiment was tried of inviting activities to recommend officers to be sent to Great Lakes or to Hampton Institute for a few weeks indoctrination in dealing with Negro

--23--

recruits. The experiment was not a success. The activities tended to employ this as a device for ridding themselves of their least desirable officers. The training schools were too understaffed and too busy to be able to do much for those who came for the indoctrination, and they were little else than passive observers. Taking charge of a Negro company was obviously the way to learn how to handle the men, but, equally obvious, the training schools could not afford the inefficiency that would result from handing their trainees over from one unskilled officer to another. Consideration was given to the plan of asking for volunteers at the white officers' indoctrination schools, and detailing enough additional men to make up a quota of 15 per month to be sent on for further indoctrination in commanding Negro units. But experience at the schools pointed to a more fundamental solution. In the acute need for capable men to be company commanders, Great Lakes had obtained a number of white Specialists (A). When it became a most difficult problem to find competent leadership for "base companies" of Negroes to be sent to the Pacific areas, a number of white Specialists (A) were obtained and the result was promising. Some of these had been commanders at Great Lakes or Hampton, and those who had not had this experience in handling colored units were sent to those schools for indoctrination before assignment to base companies. Hence, in January 1944, the Bureau recommended that up to 30 white Specialists (A) with satisfactory records as Great Lakes Negro recruit company commanders be commissioned, for assignment to units needing an officer experienced in handling Negro personnel. The Specialist (A) group promised to be a fine reservoir of talent for the program; its members had been initially chosen for their capacity to act as morale officers and represented a selective group in terms of education, maturity and experience in dealing with people (many were men whose profession was public recreation work.) The tie-up with the Specialist (A) program should have been made earlier.

--24--

The Bureau had acted too slowly in obtaining qualified white officers to lead colored units. The impetus to do something came primarily from the problem of officering Negro units being sent out of the country. But the Board of Investigation which inquired into a near riot at the St. Juliens Creek ammunition depot in May, 1943 found that inept handling by the white officers in charge as the proximate cause of that dangerous situation at a station in the continental United States. The Board pointedly recommended that

Assignment of officer personnel to organizations should be made upon qualifications for leadership and for the specific type of employment contemplated for the organization.

The provision of additional or special housing, messing or recreational facilities was one highly practical problem for most activities which received Negro sailors. Though the general outlines were much alike everywhere, the actual achievement of a satisfactory situation presented questions peculiar to each station. The Bureau therefore showed marked liberality in approving station requests. This was especially true regarding the provision of recreational facilities. This policy is notable as an instance in which the very special character of a problem led the Bureau to decentralize rather than concentrate the control of decisions. The Bureau did assist the local activities to the extent that its representatives were able to advise and pass on the experience of other stations in the course of their survey visits.

Recognizing that the Women's Reserve presented many novel problems to the activities, the Bureau issued several circular letters declaring general policies concerning the integration of the women into the establishment. No such policy letters were issued regarding the Negroes; reliance was placed on conferences with key officers in the field. Some of this could be done, though slowly, as the members of Planning and Control's special unit made their survey trips starting in the late summer of 1943. In October, 1943, a fifth Naval District

--25--

conference was attended by fifty or more officers concerned with Negro personnel, at which policy was discussed and experience passed on. This device was believed sufficiently successful; similar conferences were subsequently conducted in other areas. In the summer and fall of 1943 policy and plans were discussed at the Bureau with the personnel officers of Naval Districts concerned, who were invited in twos and threes. That it was done by conference had advantages in persuasion and flexibility over the issuance of policy letters.

Admittedly, there were difficulties in the way of a general policy for the field. In the first place, generalization itself was extremely difficult. An attempt was made to draft a statement on the key issue of segregation, but it was given up because so many qualifications had to be introduced that the document lost any helpful definiteness which it might have had.

Objections to the issuance of general policy statements on the Negro program could have been met by generalizing only to the extent that which was clearly practical and then marking out for the field the areas in which the activities must work out reasonable solutions, with Bureau support guaranteed. Even where no generalized direction could be issued, a number of variant cases could be cited to the field to illustrate the lines of Bureau thinking and to pass on experience gained in the best stations.

--26--

III. DISTRIBUTION

Once the fundamental decision had been made and enforced, that a substantial number of Negroes should be enlisted for general service, the issue to which all other questions of administration were corollary was the definition of what jobs they should do in the Navy. The types of jobs open would obviously shape the training program. They would affect the enlistment decisions of men outside the draft and the preference expressed at induction centers by selectees for Army or Navy service.

--27--

Negro Competence

Though whites and Negroes of comparable background made comparable records, the different opportunities of the races naturally were reflected in over-all comparisons of intelligence ratings, aptitudes and learning. Thus a Great Lakes survey in the fall of 1943, when the expanded program was in full swing, showed average General Classification test scores 22.2 for Negroes and 47.8 for whites with 73% of the Negroes tested scoring below 30. The following table, compiled by the educational Planning Officer, NTS Great Lakes, summarizes overall group performances in tests in the summer of 1943:

| Scores for All Recruits | ||||||

| GCT | Read. | Math. | Mech. Apt. | Mech. Knowledge | Elec. Knowledge | |

| White: | 48 | 44 | 44 | 47 | 48 | 49 |

| Negro: | 34 | 34 | 30 | 35 | 26 | 37 |

| Scores for School Selectees | ||||||

| White: | 57 | 53 | 51 | 53 | 50 | 51 |

| Negro(1): | 48 | 53 | 39 | 41 | 35 | 42 |

| Negro(2) | 53* | 48 | 43 | 44 | 37 | 47 |

| *Excluding Cooks and Bakers | ||||||

These comparisons of the racial groups taken as wholes were reflected in Service school quotas. At the time of the tests summarized in the above table, about 35% of the whites going through recruit training at Great Lakes were selected for service school training; about 31% of the Negroes. The Negro 31%, however, included 500 men per month entering the Cooks and Bakers school, which had the lowest requirements of the Class A schools. As of early September, 1943, about 40% of all enlisted personnel graduated from recruit training were sent to Class A schools; about 33.14% of Negro recruits went to Class A schools. In April, 1944, the Class A school quota was set at a new low point of about 23%. Behind the tendency for this percentage to decline were causes somewhat more

--28--

complex than can be fairly summed up in the simple statement that there were not enough qualified colored personnel available to fill the schools to higher levels. This was in large part true. It was also true, though for reasons no one could explain, that the quality of the particular Negro input under Selective Service dropped in the months before April, 1944. School quotas were cut in some cases because there were no more billets for the ratings within the Navy's general framework of the use of the colored men. The classification unit at Great Lakes estimated that 25% of Negro recruit school graduates were qualified for Class A school training; a comparable estimate for whites was 40-50%. On the whole, the experience was that every qualified Negro could go to a Service School, but there sometimes were not enough to fill the quotas.

Two factors remain to make a balanced picture of the quality of the Navy's Negroes. First, the Navy did not get as good quality as it might have. This is suggested by the relative concentration of illiterates (here defined as individuals having less than four year's of schooling) in the service and in the general Negro population. While Negro illiterates reporting at Great Lakes 1943 amounted to 30% of colored recruits reporting there, the percent of male Negro illiterates between the ages of eighteen and forty-four was estimated for the country as a whole in 1940 (World Almanac, 1943) as 23.4; corresponding estimates for age groups 18-20 and 21-24 were respectively 17.6 and 20.6.

The second factor which must be weighed in appraising the quality of the Navy's Negroes is that their handicaps were of a sort which experience proved could be overcome to a degree, even in the limited training time available. They did not make as good a showing at learning as did the whites; Negro test grades at Great Lakes at best tended to run about 10 points below whites. Morale is an important factor in learning, however, and the typical Negro recruit at Great Lakes took his Navy training as an opportunity for advancement. A report of the Educational Planning Officer at Great Lakes noted this:

--29--

The achievement of the Negroes is consistently somewhat lower then that of the white students. The background experience conducive to efficient learning is markedly lower for Negroes than for whites. The Negro students make up for their poorer background to some extent through their greater earnestness and effort.

There was testimony to this earnestness in the fact that thousands of men worked hard at the remedial school in the three R's at Great Lakes, two hours a night five nights a week and two hours on their free Saturday afternoons, all simultaneously carrying on the regular drill schedule. All instruction was by Negro college men who volunteered their time. At the end of the six weeks course, 72% of the illiterate men who took it were able to pass fourth grade examinations. In service schools, Negro test scores were consistently lower than whites, under equally competent instructors and in smaller classes. Scores were lower in one test machinists' mates class, though twice the time was taken to cover the same material given white students. However, Great Lakes instructors were reported by the Educational Planning Officer as in agreement that generally where the Negroes were given longer training, they showed up about as well as whites in shop work, though their poor background held them back in advanced mathematics and theory subjects. Learning continued on the job, and although the Bureau did not conduct any scientifically directed check on rates of progress, field surveys by its representatives as well as various reports from activities generally agreed that the Negroes learned and carried on their duties with greater efficiency than had been anticipated.

In the fall of 1943 the Bureau achieved a reasonably wide distribution of colored personnel among District activities. minimizing the creation of large, segregated groups. The tightening manpower situation and the increasing difficulty in finding billets for the numbers of Negroes inducted under Selective Service tended to reinforce this policy development. This was underlined by the approval

--30--

by the President in May, 1944, of the Bureau's request for approval not to exceed ten percent of any station's complement.

Policy consisted not only in refraining from Negro assignments to certain areas, but also in the care taken to avoid sending northern Negroes to such southern activities as did receive colored personnel. In making up drafts, Great Lakes even sought, where possible, to send men back to the same district in which they were enrolled. A curious converse problem arose. It was felt that experience showed that Negroes had a greater tendency than whites to bring their families to the area where they where stationed. Because of this ComTHREE requested that Negroes who came from New York City be detailed back there, to prevent further pressure on the city's overcrowded Negro districts caused by an influx of new families. The Bureau agreed that the request was reasonable, and noted that it could not be fully carried out:

Of the Negroes inducted into the Navy 65% or more are from Southern states. However, considerably less than 45% of the enlisted personnel in the Continental United States are stationed in Southern Naval Districts.

A difficulty in following the policy as to the South was, that most of the men qualified for ratings were Northerners.

Procurement of Negro Officers

There were two lines of possible development: the admission of Negroes to the V-12, or college program, under which young men were permitted to enlist as apprentice seamen, after passing a competitive examination given throughout the country, and then permitted to attend college, taking a course preparatory to attending officer's indoctrination school; or, the commissioning of men direct from civilian life or from the enlisted ranks. The second, being the shorter route was the principal focus of controversy.

--31--

Shortly after the Negro training school at Hampton Institute was established, a white instructor there suggested informally to the Bureau that it would be beneficial to commission a few Negro members of the Hampton faculty who were instructing the Navy trainees. This suggestion was not accepted. The President's order that, starting in February, 1943 the Navy must take all draft-age men via Selective Service, and that it must take a fair share of Negroes thereunder, first made Negro commissions a real issue in the Bureau. In that month the estimate was made that as a result of these orders there would by December 21, 1943 be perhaps 125,000 Negroes in the Navy, 100,000 of whom would have entered under the Selective Service Act. Not only did that act stipulate that "in the selection and training of men under this Act ... there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race or color", but the sheer weight of the fact of over 100,000 Negroes with no Negro officers would give added impact to former pressures. A memorandum within the Bureau recommended that plans be made immediately to commission 50 Negroes from civilian life and to scan the enlisted ranks for an additional qualified 25; that these men be sent to indoctrination; and that they be assigned to activities already having large numbers of Negro enlisted men where the issue of social mixture would not be acute, such as the Naval Ammunition Depots. These recommendations were rejected by the Bureau but the problem of the commissioning of Negroes continued to be considered.

On December 2, 1943, the Chief of Bureau recommended to SecNav that the Navy commission 12 line and 10 staff officers, of the Negro race. Two of the line would be destined for instructional posts at Hampton Institute and the other 10 for Great Lakes. They would be designated, after an indoctrination period at Great Lakes from a group of about 20 men to be selected from the enlisted ranks on the school's nominations from their best graduates. Staff officers would be selected direct from civilian life; indoctrinated at Great Lakes and assigned

--32--

to the staffs of the two training schools; there would be two each in the, Chaplains, Dental, Medical, Civil Engineers and Supply Corps, respectively. The Bureau letter noted that the consent of the other Bureaus concerned had been indicated. The Chief of Bureau based his recommendation on the fact that the Navy then had 82,000 Negro enlisted men in all pay grades, many of whom were being advanced every month and from whom a carefully selected list of officer material was available. He pointed out that many activities were now manned wholly or substantially by Negroes, where Negro officers could be used without undue difficulty.

CominCh endorsed the recommendation, December 15, 1943, and SecNav approved it December 18, 1943, cautioning, however, that

After you have commissioned the twenty-two officers you suggest, I think this matter should again be reviewed before any additional colored officers are commissioned.

Subsequently SecNav approved the Bureau's recommendation that in addition to the 22 appointments already approved, it be authorized to promote to warrant rank not to exceed four of the men nominated to the officer candidate group who appeared outstandingly qualified with respect to all but formal education.

The nomination of the line officer candidates had already been secured, and in January, 1944, these men reported to Great Lakes for indoctrination. Allowance was made for 25% attrition. Care was taken to select men who were not "extreme" in their attitudes; on the other hand, the schools picked men of character and self respect. It was thought wise to put the men through a uniform training, and all were sent to Great Lakes.

The staff officer side of the program did not move as fast, because the other Bureaus and the Chaplains Corps were slow to find candidates. One logical

--33--

change was made in the first plan that all should be commissioned from civilian life; there was no reason why the chance should be denied enlisted men, and two candidates for BuSandA's posts were thus finally found within the Service.

The terms of the Army-Navy college training plan for officer candidates, as announced December 17, 1942, contained no limitation of race or color though neither did it contain an explicit ban on discrimination. In the fall of 1943 SecNav answered a request of the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association for a statement on the Navy's policy regarding admission of Negroes to the college program by saying that this had been deemed unnecessary in view of the fact that the original announcement created no racial barrier. It was found desirable on December 15, 1943, to issue Bureau Circular Letter 269-43, emphasizing to all activities that enlisted men were entitled to consideration for transfer to the V-12 program without discrimination on account of race. This letter was issued in part because both the Great Lakes and Hampton Schools had urged it as a needed offset to feeling among trainees that the V-12 program was barred to colored boys.

A few Negroes in fact entered the college program. Two were placed on active duty in the program July 1, 1943 and nine others on November 1, 1943; six of these eleven entered the program from civilian life, five from naval service. No special colleges were designated for Negroes' attendance. No special Negro quotas were set; the Bureau's December 15, 1943 letter stated that this would in itself have been discrimination and that Negroes who won entrance to the program should do so in the general competitive examinations on the same basis as whites and not as "representatives" of their race.

The strongest justification for the delay in the colored officer program, was put by a white officer experienced in the training of Negroes at Great Lakes. In an address at Chicago's DuSable High School, November 11, 1943, he said

--34--

My own opinion is that there would have been no surer way for this program to have ended in disaster than by the commissioning of officers before either the prospective officers or the men whom they were to command were trained to discharge the duties and responsibilities incumbent upon them in a satisfactory manner. It was not like the Army where there were already well-trained regiments with tradition behind them that could quickly be expanded.

(2) Petty Officers

Ratings for Negroes presented two different questions. There was the issue of the variety of assignments to be made available and the matter of job segregation. And there was the issue of military command. The two were of course not wholly distinct; one strong argument made for holding Negroes to a narrow range of billets was that otherwise the races would have to be mingled and the problem of Negro petty officers exercising command over white seamen would present itself.

But the more experimentally-minded CO's receiving Negro drafts began to report - as they did, for example, at the FIFTH Naval District conference on the Negro Program, October 26, 1943 - that the most efficient way to build an integrated unit was through well selected Negro "boss men". The Bureau pointed out that first reports of poor results from Negro petty officers must be weighed in light of the fact that these were frequently merely Coxswain, with no more training or experience than the men they were to lead. Great Lakes instituted special "leadership training" to supplement teaching of skills at service schools, as will be noted, a Negro Specialist (A) program was developed, to provide the sort of competence which wins respect. That such steps were none too early was indicated by disquieting reports in the fall of 1943 regarding deterioration of morale and discipline among "base companies" delayed in idleness on the west

--35--

coast awaiting Pacific duty. Difficulties were attributed largely to lack of enough Negro leaders. The influence of these factors was seen in an increasing liberality in the Bureau's approval of Negro petty officer billets in complements.

There were some claims of discrimination in denial of petty officer opportunities to Negroes. Most of these, however, really involved the alleged denial to Negroes of the chance to learn and practice the more skilled assignments rather than protests over denial of the privilege of command. There are two noteworthy issues over the exercise of military authority. The first rose out of the careful instructions given Negro shore patrols that they make no effort to discipline whites, and that even in case of a fight between men of different races, they restrict themselves to handling the colored participants. This seems clearly one of the practical adjustments necessary in accommodating incidents of the Negro program to the existing difficulties in the race situation. The second controversy arose out of BuNav Circular Letter No. 62-42, April 21, 1942, which established the ratings of Officers' Chief Steward and Officers' Chief Cook, and stated that

Pending change in the Uniform Regulations, Officers' Chief Stewards and Officers' Chief Cooks will wear the Chief Petty Officers' uniform with the current insignia of the rating group.

Some months later the indicated change was made, in the form of a differentiation of the insignia. The Bureau was flooded with protests over this as a willful insult to the men who had already been proudly wearing the eagle. In reply, the Bureau pointed out that the new rating had been created to open the highest enlisted pay grades and give honor to men who had served long and well in the Stewards' Branch, and that the objectionable change in no way

--36--

altered the pay or other priveleges, but simply the insignia. It was stated that the new ratings had never been intended to carry military authority over personnel in other branches, but that cases had arisen in which such authority was sought to be exercised; the change in insignia was simply part of "a clarification of the status" of the new ratings.

In January 1944, 30 men who had already had substantial experience of the sort desired in handling Negro recruits at the training schools were rated and 60 more were sent to special training for the rate at Bainbridge. Also in January, 1944, the Bureau specifically recommended the inclusion of two Negro specialists (A) in each base company sent out of the country.

Bureau surveys showed in the early summer of 1943 that there was a use for Negro Shore Patrols in certain areas. For obvious reasons, special care in selection and training was indicated. This had been done on a local basis with initial success as at NAD, Mare Island. In July, 1943, a training program was authorized to be conducted at Great Lakes, leading to the rating of men as Specialists (S). The first selections of men for the program were not altogether satisfactory. In December, 1943, ComNINE relieved a number of the men first sent for the duty as clearly unqualified by maturity, temperament or physique. After that, selection and training went more successfully. This was helped by a specification of selection standards. In particular, it had been learned that the desired number of men could not be obtained from men with police experience; efforts were concentrated on finding men 25 years or over, medium to tall, well proportioned, in excellent physical condition, and demonstrating maturity of judgment.

--37--

Bureau field surveys indicated that liberal policy should be followed in allowing activities with large numbers of Negroes to receive Specialists (S) in excess of complement. This was felt necessary, because it was believed Negro units would require a greater number of these ratings than white units and also because outstanding Bureau instructions, that Negroes be used only in rates for which trained, would prevent activities from following the practice common in the case of white petty officers, of using Coxswains and Boatswains as masters at arms. The latter difficulty was finally met by special provisions for rating Negroes BMA [Boatswain's Mate], to perform master at arms duties. Special provision was necessary because, since Negroes had been in the Navy in large number for only a comparatively short time, only a limited number could be found with the requirements for a BMA rating; hence it was provided that Negro petty officers of other ratings might be changed to BMA on request of Commanding Officer, and that when qualified, Negro Seamen strikers for BMA might be rated Coxswain (there being no BMA 3/c).

For obvious reasons, caution had to be exercised in the policies of using Negro Shore Patrols. Specialists (S) were detailed for this duty only when the Bureau knew that this met the approval of responsible officers in the area involved. In August, 1943, ComFIVE disapproved the plan to train Negroes for this duty at all, expressing grave fears of the trouble that would follow assignment to this duty of Negroes not familiar with the laws and customs of the area involved. Grounds for caution were reflected in the statement of policy by the Bureau in its general letter of October 1, 1943, announcing the creation of the Specialists (S) school.

--38--

Each graduate of the school, it declared. would be assigned only to a district in which he had lived during most of the past ten years before entering the Navy

in order that he may be assigned Shore Patrol Duties to supervise Negro personnel in Negro districts of towns and larger cities having laws and customs with which he is thoroughly indoctrinated.

The letter emphasized that Negro Shore Patrols must be used within carefully defined bounds of policy in each area:

The use of Negro Shore Patrols under circumstances or in environment prejudiced either to military discipline control or to the established racial views of the specific community is not contemplated. In the administration of Negro Shore Patrol Activities, Commanding Officers must definitely delimit the duties to be performed to avoid controversial incidents.

--39--

"Sea duty" for Negroes

(1) The Fleet

For almost a year after general service enlistment was opened to Negroes, it was so firm an assumption that they would not serve in the Fleet that the matter was scarcely discussed. The General Board's report of March 20, 1942 outlining what proved the framework of the initial program, is the most extended analysis. The report stated

That any practical plan, which would not inject into the whole personnel of the Navy the race question, but provide for (a) Segregation of colored enlisted men, insofar as quartering, messing and employment is concerned, (b) Limitation of authority of colored petty officers to subordinates of their own race.

Analyzing ship's organization and the nature of the duties of various branches and rates, the Board concluded that, consistent with its basic assumptions, Negroes could not be enlisted in selected ratings in designated branches, nor in any branch (in addition to Stewards branch) wholly turned over to them. This meant that all-Negro units must be formed. But the training that would be necessary to provide all-Negro crews for such naval auxiliaries as transports, AK's, ammunition vessels or Fleet oilers led the Board to conclude that

This prospect would involve an effort out of all proportion to the return in effective seagoing units which could be expected on the basis of the Navy's actual experience with vessels manned by crews of other than the white race.

The difficulties of replacement and rotation of personnel in connection with the operation of a limited number of all-Negro ships, were noted.

A suggestion made in the first plans was that Negroes be trained as communications personnel for assignment aboard merchantmen. This was dropped after it was discovered that the number of men qualified for Class A schools would at best only be large enough to supply rated billets necessary in the larger portions of the program.

--40--

A memorandum to the Chief of Bureau, April 1, 1943, presented a listing of assignments which might absorb the 125,000 Negroes which War Manpower Commission demanded the Navy take by the end of that year, but suggested that

...the inclusion of Negroes in small numbers in the crews of the larger combatant ships offers a better solution of the problem of absorbing such large numbers of Negroes and is the only means by which any appreciable reduction can be made in the high percentage of Negroes that will be concentrated in all shore activities...

Meanwhile heightened problems of morale and tension were created by large concentrations of Negro personnel in shore activities, by white sentiments that Negroes were not sharing the fighting, and by Negro resentment against being barred from the fighting. There was also the possibility that efficiency would drop from the staffing of shore activities with many less skilled men. Due to this situation memoranda within the Bureau pressed at intervals throughout 1943 for inclusion of Negroes in Fleet vessels. It was ruled, however, that though Negroes would be considered for inclusion in ship Repair Units on the same terms as whites, they would not be assigned to such Units aboard repair ships; several recommendations for assigning Negroes to some LST's, LCI's and LCT's during the great expansion of the amphibious program were rejected; pursuant to a recommendation by VCNO, a Bureau letter of October 9, 1943 stated that Negroes should not be assigned to YN's or YMS's, because these vessels were operated in readiness for overseas assignment and required a deck force thoroughly competent in seamanship; likewise rejected was a recommendation to the Chief of Bureau, made in October, 1943, that a percentage of the fireman and seaman complements be filled with Negroes aboard a new construction CV, CVE, APA, AKA, BB and AO. One new DE (USS Mason) and one new PC (No. 1264) to be commissioned early in

--41--

1944, would be manned so far as possible by enlisted Negroes under white officers; all enlisted billets would be filled by Negroes as soon as men qualified to fill them had been trained.

Despite the special problems the Negro personnel of the USS Mason were Judged by Bureau observers to have achieved an average competence in their shakedown cruise. At this time, the Mason carried 196 Negroes, 89 of whom were rated or strikers for rates, 9 of whom were firemen and 98 seamen. Extra accommodations permitted overcomplementing the ship in some ratings particularly requiring special skill, so that training might be expedited. In selection of the colored personnel, the first thought had been that the crew should be a cross section of the Navy' s Negroes; but, as stated in a letter to the Training Officer, NOB Norfolk, this was changed

on the premise that all Commanding Officers deserve the best crews that can be furnished, whether Negro or white. Therefore, although the men for the crew were not picked by name, the orders did state that they were to be competent, and, where possible, from among those serving aboard Local Defense and District Craft.

The petty officers proved, as a result, to be on the whole a satisfactory group, marked by competence in their rates and interest in their work. The Bureau observers agreed that rated personnel in general were inadequately indoctrinated in their military responsibilities for the maintenance of discipline. This last factor is related to the quality of the deck force. The Bureau had instructed the Naval Districts that men should be detached for this service as a reward for outstanding service. At the end of the shakedown cruise, arrangements were made to replace ten non-rated men of the deck force who had been particular sources of difficulty. The experience suggested that it would have been better had the seamen and firemen been detailed to the ship direct from recruit training at Great Lakes and the

--42--

School at Hampton, save for the men needed at the outset for the nucleus crew. The Bureau observers were in agreement, that the poor selection of the deck force held back the Mason's performance. The ship did not in fact have the all-around picked crew which the Bureau' s instructions had indicated.

White personnel aboard the Mason included ten officers, 12 Chief Petty Officers and several first and second-class petty officers. There were no Negro officers, and, at the outset, no Negro petty officers above second class. In addition to the ship's regular officers, two Bureau observers spent roughly two months with the Mason during its shakedown period in order better to observe the work of the crew.

None of the ship's regular officers nor any of the white petty officers had had any special indoctrination or experience in the handling of colored personnel. The white men aboard were not volunteers for the duty. This had no apparent result on the effectiveness of the officers, but there was evidence that the white petty officers in general did not like their duty and apparently accepted it primarily with the hope that it meant more rapid advancement in ratings (an expectation lacking foundation.) The white officers and chief petty officers evidently did not realize how hard a problem they would have in keeping a clean ship, and, lacking a proper background for handling the matter, the petty officers tended to become discouraged and quit their efforts. However, below deck spaces were kept orderly and clean as a result of close supervision though there was some difficulty regarding the care of clothing. The need for greater attention to details of morale and discipline when dealing with colored men was noted as even more apparent aboard ship than at shore establishments. There was

--43--

a general tendency among all non-rated men aboard to show a lack of respect for both white and colored petty officers, and some disinclination among colored petty officers to put their men on report. An incident occurring at NOB Bermuda suggests the importance of an adequate understanding on the part of those in charge of the particular problems of handling Negro personnel. At the request of the DE-DD Shakedown Task Group Commander, no liberty was granted the Mason's crew during the schedules period of exercises. This was a discrimination, since crews from other ships present were granted liberty; but the inequality of course caused special resentment among the Negro personnel, with whom the issue of discrimination is always particularly sensitive. Finally, during the Mason's fifth and last week in the area, the Commanding Officer wisely took it upon himself to grant liberty. The ship's liberty parties were well behaved.