Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Hampton Roads

Virginia

8–9 March 1862

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP

Lieutenant John L. Worden, United States Navy (USN)

Lieutenant Samuel D. Greene, USN

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Captain Franklin Buchanan, Confederate States Navy (CSN)

Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones, CSN

BACKGROUND

The steam frigate USS Merrimack was launched in 1855 at Boston Nay Yard, Massachusetts. In April 1861, this now-decommissioned vessel was awaiting repairs at Gosport Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia. On 10 April, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles pushed the yard’s commander, Commodore Charles McCauley, to hasten its repairs and prepare the vessel for removal to Philadelphia. However, his message to McCauley also came with a subtle disclaimer to avoid causing “needless alarm.”[1] The state of Virginia had not yet voted to secede from the union, and there was no desire in Washington to expedite their decision. When McCauley replied that it would take at least a month to repair the vessel, Welles was outraged.[2] Welles sent Benjamin F. Isherwood, engineer in chief of the Navy, to assess the truth of the situation. Isherwood finished the work in less than a week and prepared the vessel to depart Norfolk.[3]

A week later, the State Convention of Virginia voted for secession. A day after the vote, Isherwood told McCauley that Merrimack was ready, but McCauley replied that the ship would not be leaving.[4] Hearing this news, Welles sent Commodore Hiram Paulding, of Pawnee, to replace McCauley in command of the yard. However, Paulding arrived too late to stop what came next. Fearful of an uprising in the local population, McCauley decided to abandon the yard, but not before burning it to the ground, spiking all the cannons, and scuttling or sinking all of the ships, including Merrimack. When Federal reinforcements arrived with Commodore Paulding, they could do little except try to finish the job that McCauley had started and tow one of the few remaining ships, the wooden sailing frigate Cumberland, to Fort Monroe. The retreating Federals still failed to destroy the dry dock, which gave the Confederates the capability to berth a ship of any size and repair it. [5]

Soon after the departure of Pawnee, Major General William Taliaferro and the Virginia state militia moved in to take control of the yard. The Federal army retained Fort Monroe, which allowed them to blockade the entrance to Hampton Roads. The Confederate navy had little hope of breaking the blockade at the start of the war. Having no facilities or supplies to build enough ships to outnumber their enemy’s fleet, their only hope was technological advancement. In May 1861, Stephen Mallory, the Confederate secretary of the navy, wrote, “not only does economy but naval success dictate the wisdom and expediency of fighting iron against wood.”[6] Mallory sent representatives to buy these vessels from England or France, but he also made other plans. There was no doubt of his intent to salvage the burned out Merrimack; the Confederate navy needed every vessel that they could find to break the blockade.

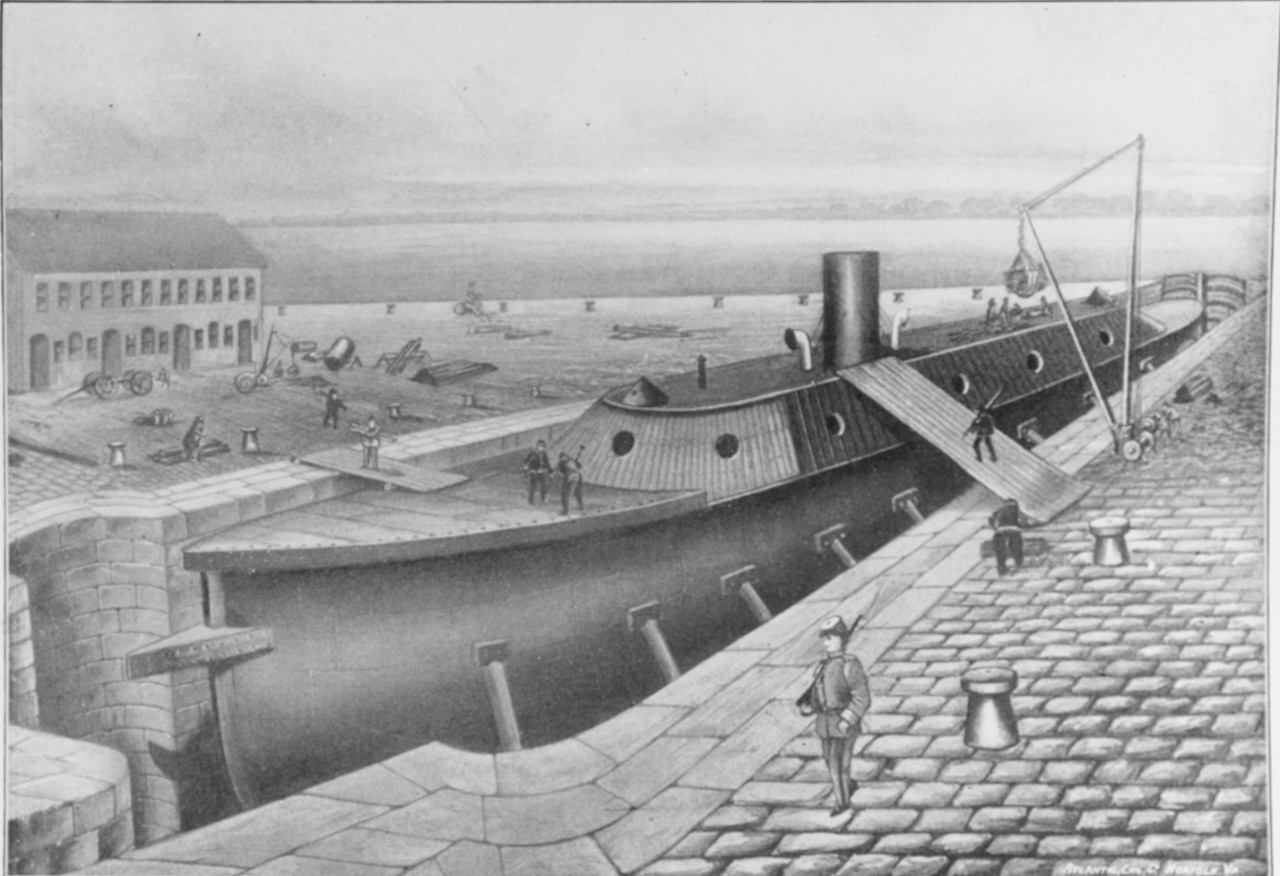

In late May, French Forrest, the new commandant of the Confederate States Navy Yard at Gosport, reported the successful raising of Merrimack.[7] Over the next nine months, the yard workers converted the burned-out vessel into a casemate ironclad ram, which was renamed CSS Virginia. Lieutenant John M. Brooke and Lieutenant John L. Porter both prepared the designs for transforming Merrimack. Iron plating protected everything above the water. Unfortunately, the weight of this plating contributed to the vessel’s deep draft of 22 feet. Limited iron supply and production capability slowed down the construction of the jury-rigged ironclad. It took nine months to complete construction of the vessel intended to defend Hampton Roads and the Confederacy.

PRELUDE

As word spread of the Confederacy’s plans for Merrimack, the Federals felt the need to counter this threat, which led to the establishment of the ironclad board. On 3 August, the department of the Navy released an advertisement for proposals from designers for “iron-clad steam vessels of war.”[8] Welles assigned Commodore Hiram Paulding, Commodore Joseph Smith, and Commander Charles H. Davis to the new board for their construction.

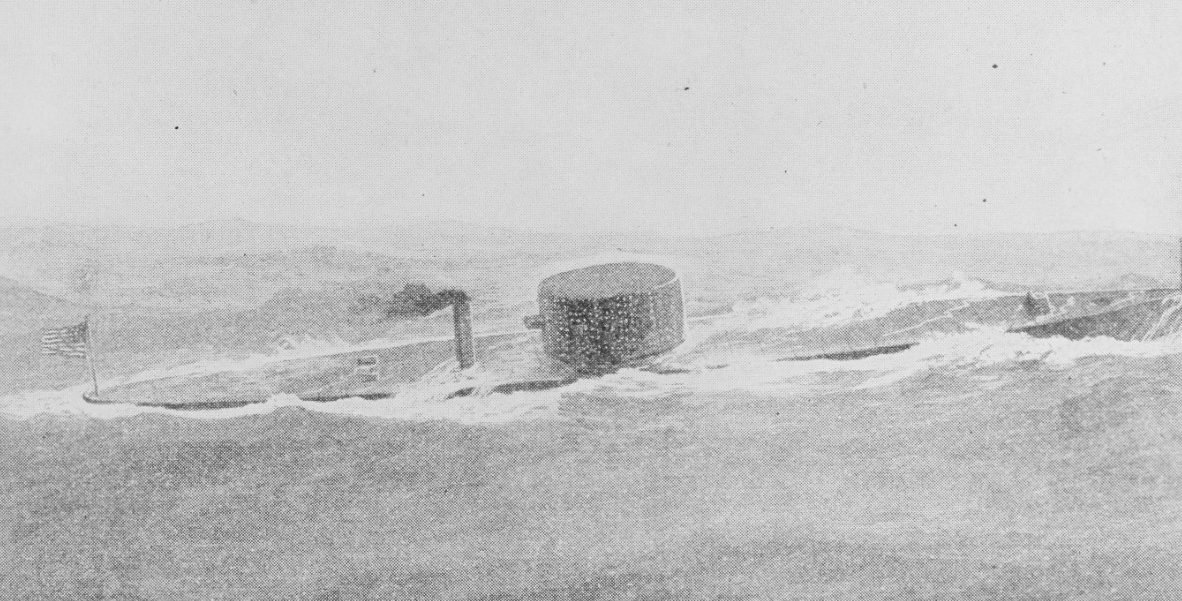

John Ericsson, a Swedish engineer, initially contacted Abraham Lincoln with his plans for an ironclad, but he received no response until the intervention of Cornelius Bushnell, a Connecticut businessperson and shipbuilder. Bushnell sought Ericsson out for his opinion on one of the other proposed ironclad vessels, Galena. With Bushnell’s support, Ericsson’s own plans became a reality with the construction of the USS Monitor.[9] Lieutenant John L. Worden received command of the new ironclad. Although warned that the vessel was an experiment, Worden seemed excited about the its capabilities.[10] Worden launched the unfinished ironclad on 30 January 1862 from the New York Navy Yard. Welles planned to send the vessel to face the Confederate ironclad at Norfolk as soon as possible.[11] However, the experimental vessel had yet to complete its sea trials.

On 17 February, CSS Virginia was launched at Gosport.[12] The still unfinished vessel received no fanfare as the yard’s commandant, French Forrest, ordered the officers and the crew to begin putting the vessel in order immediately.[13] On 24 February, Mallory named Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan as the Confederate commander of the naval defenses of the James River. Buchanan chose Virginia as his flagship, as Mallory had great hopes for its maiden voyage. Unfortunately, a lack of gunpowder delayed any attack on the enemy blockade.[14] While he waited, Buchanan did not stay idle. On 2 March, he wrote to General J. Bankhead Magruder, in command of the Confederate forces at Yorktown, asking for cooperation.[15] Unfortunately, Magruder could not see an effective way to support Buchanan’s planned attack at Newport News.[16] On 7 March, Mallory confidentially suggested an attack on New York City to Buchanan.[17] Despite this somewhat fantastical proposal,, Buchanan remained focused on his next targets afloat off Newport News Point.[18]

On 5 March 1862, Worden completed the sea trials for USS Monitor and was ready to leave New York. Delayed by a steering malfunction, he left a day later. On 6 March, the tug Seth Low departed New York City towing the unstable ironclad down the Atlantic coast toward Hampton Roads. At the end of the first day, chief engineer Alban Stimers, an observer on this maiden voyage, was in awe of the ship’s buoyancy.[19] However, a storm blew in on the second day, causing water to wash over the deck and the blower system that provided air to those below deck stopped working. Without working blowers, no one could work below deck. While the tug pulled the ironclad into calmer waters, Stimers played an important role in fixing the blower system and getting the new invention to its first destination.[20]

BATTLE

On 8 March 1862, CSS Virginia (formerly Merrimack) emerged from the Gosport navy yard. With an average speed of only five knots, the vessel made slow progress on the Elizabeth River, tended by Beaufort and Raleigh. Entering Hampton Roads, Buchanan could see the five Federal warships off the opposite shore, with the sailing sloop Cumberland and the frigate Congress anchored off Newport News, near the entrance to the James River. The wooden-hulled frigates St. Lawrence, Minnesota, and Roanoke were farther east near Fort Monroe. At 1330, Buchanan dropped his towline to Beaufort and headed straight for Cumberland. This was the only vessel that Buchanan feared might have the firepower to damage Virginia.[21]![]() The Confederate James River Squadron (Patrick Henry, Jamestown, and Teaser) formed a line emerging from the James River and headed for the imminent action at Newport News. The Federal frigates Minnesota and Roanoke also headed toward Newport News from the opposite direction. The Federal steamer Cambridge began moving to tow St. Lawrence into position.[22]

The Confederate James River Squadron (Patrick Henry, Jamestown, and Teaser) formed a line emerging from the James River and headed for the imminent action at Newport News. The Federal frigates Minnesota and Roanoke also headed toward Newport News from the opposite direction. The Federal steamer Cambridge began moving to tow St. Lawrence into position.[22]![]()

As Virginia steamed slowly across Hampton Roads, a shot from USS Congress bounced off the thick armor of the Confederate ironclad. At 1420, Beaufort fired at Congress as the Confederate fleet approached and prepared to pass the frigate. Buchanan fired broadside into Congress as they passed, but kept his eyes on Cumberland. The ram of Virginia hit the starboard side of the large wooden sloop-of-war. Drawing back and firing again, the Confederate ironclad rammed the sinking ship a second time.

Xanthus Smith, Rebel Ironclad Merrimac Destroying the US Frigate Congress, c. 1862. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum, MO 1957.44)

In attempting to get underway, Congress ran aground. Still within range of Virginia, the crew of Congress returned fire for an hour before the ship’s executive officer, Lieutenant Austin Pendergrast, raised the white flag at 1600. Buchanan ordered Lieutenant William Parker, in command of Beaufort, forward to receive its surrender, accompanied by Raleigh.[23] Buchanan gave orders for the officers to be taken as prisoners and the remaining men to be allowed to swim ashore. During the surrender, there was a volley of fire from the shore. Buchanan had emerged from the ironclad hull of his vessel to watch the proceedings. During this exchange of fire, he was wounded. Angered by this lack of civility, he ordered the burning of Congress. With Buchanan injured, the command of Virginia passed to his executive officer, Lieutenant Catesby ap R. Jones.[24]

Three Federal frigates had run aground trying to move closer to Newport News.[25] Two of the frigates, St. Lawrence and Roanoke, had been pulled off by tugs and moved under the protection of the guns from Fort Monroe, but Minnesota remained stuck. Moving away from the burning Congress, Jones headed for Minnesota. At 1600, Virginia, Jamestown, and Patrick Henry converged on the grounded frigate. However, the deep draft of the Confederate ironclad did not allow it to get closer than a mile from the target. Jamestown and Patrick Henry had better positions, but the return fire from Minnesota soon forced them into retreat. After darkness came, the Confederate squadron slipped away from the crippled frigate and moved off to Sewell’s Point to await a new day.[26]

Unfortunately, the recoil of Minnesota’s guns had pushed the ship further into the mud.[27] A fleet of steam tugs approached the frigate, and their crews worked through the night to attempt to drag it off the bar.[28] On the evening of 8 March, Worden and Monitor reported to Captain John Marston, commanding officer of Roanoke and the present senior officer. Marston assigned Monitor to the protection of Minnesota. Shortly after midnight, Congress exploded. On its first day of battle, the Confederate ironclad Virginia had destroyed two warships.

On the morning of 9 March 1862, Jones brought Virginia out to finish the carnage begun the day before. Heading toward Minnesota, still aground, Jones did not expect the appearance of an ironclad adversary from behind the stranded vessel.[29] Monitor opened fire, compelling all of the wooden-hulled enemy vessels to retreat except for Virginia. For the next four hours, the two ships circled each other. The explosion of a shell against the pilothouse on Monitor injured Lieutenant Worden. Temporarily blinded, Worden handed over command to his executive officer, Lieutenant S. Dana Greene. Monitor withdrew into the shoals during the change of command.

This withdrawal seemed like the perfect moment for Jones to renew the attack on Minnesota. Jones’ fellow officers convinced him to retire due to the falling tide and the damage to Virginia.[30] The new commander of Monitor watched the Confederate ironclad retreat, but he had “strict orders to act on the defensive and protect the Minnesota.”[31] During the return to Sewell’s Point, Jones’ officers convinced their commander to return to the yard for repairs. The next day, Virginia was back in the dry dock. During the night, the tugs finally freed Minnesota from the shoal. When Virginia failed to appear on the following day, it became clear that the battle was over.

U.S. Army reconnaissance map of the Hampton Roads vicinity showing enemy positions, c. 1862. (LC, 2003630497)

AFTERMATH

There was no clear winner in the contest between the ironclads, although both sides claimed victory. With the withdrawal of Virginia, the danger to Minnesota was temporarily removed. In the early morning of 10 March, the tugs were finally able to refloat the frigate and ease her off the sand bar. With the frigate out of danger, the Federal navy had achieved a tactical victory in this battle. Monitor had fulfilled its duty to protect the ship whereas Virginia had failed to destroy it.

This battle was a strategic victory for the Confederacy, but it was not a complete one. Despite the destruction of Cumberland and Congress, the failure of the Confederate army to coordinate with the attack by Virginia meant that Federal army retained its toehold at Fort Monroe. The Federal fleet withdrew most of its vessels to the open sea and did not attempt to retake the roads, but the blockade remained in effect. The presence of the Confederate ironclad blocked any Federal access to the James River, which meant that Major General George McClellan, commanding the Federal land forces on the Virginia Peninsula, needed a new operational approach.

Under pressure from Washington, McClellan quickly made plans to land at Fort Monroe and move overland toward Richmond. He sought reassurance from Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox that Monitor was a match for Virginia.[32] Although Fox was confident of the capabilities of the ironclad, he advised against McClellan’s full reliance on one vessel.[33] On 17 March 1862, McClellan landed his army and all of its supplies at Fort Monroe and embarked on a new campaign to take Richmond.

Virginia was back in the dry dock three days after it had left the first time. Buchanan’s wounds did not allow him to resume his command. Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall assumed command of the ironclad while it was still in dry dock.[34] Tattnall was aware that the enemy hoped to draw Virginia out into the open sea and ram it.[35] Thus, Virginia remained guarding the entrance to the James River and impeding any Federal advance to the Confederate capital.

As the Federal army prepared to advance up the peninsula, the Navy prepared for their next opportunity to engage Virginia. The commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, issued orders for every Federal vessel in the roads to guard against Virginia making a move to go to Yorktown.[36] He essentially put his entire fleet in Hampton Roads on defense.

On 11 April, Virginia reemerged for battle accompanied by four gunboats and two tugs, stopping near Sewell’s Point.[37] Out of the range of the guns of Fort Monroe, Tattnall waited to see if Monitor accepted his challenge. Aboard Monitor, Lieutenant Commanding William Jeffers followed his orders and resisted the urge to attack. Both vessels acted as a deterrent for the other until the Confederate forces fell back toward Richmond. Virginia was left alone and unable to ascend the James River due to its deep draft. On 11 May 1862, Tattnall scuttled the vessel, an act for which he was later court-martialed (and then acquitted). With the destruction of the Confederate ironclad, the Federal squadron advanced up the James River toward Richmond.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

Schneller, Robert J., Jr. "The Battle of Hampton Roads, Origins of Ordnance Testing Against Armor." International Journal of Naval History (December 2003/2004) [PDF]

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

The Battle of Hampton Roads, by Anna Gibson Holloway, The USS Monitor Center.

Monitor 150th Anniversary—Battle of Hampton Roads, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

FURTHER READING

Holzer, Harold, and Tim Mulligan. The Battle of Hampton Roads: New Perspectives on the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia. New York: Fordham University Press, 2006.

Hughes, Dwight Sturtevant. Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle of Hampton Roads, March 8–9, 1862. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, LLC, 2021.

***

NOTES

[1] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the the Rebellion Series 1, Vol. 4 (Washington: Government Printing Office (GPO), 1896), 274.

[2] Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles: Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, Vol. 1 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 43.

[3] ORN, 1, 4, 280–81.

[4] ORN, 1, 4, 281.

[5] ORN, 1, 4, 288–98.

[6] ORN, 2, 2, 69.

[7] ORN, 1, 5, 801.

[8] Report of the Secretary of the Navy in Relation to Armored Vessels (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1864), 2.

[9] Anna Gibson Holloway, and Jonathan W. White. “Our Little Monitor": The Greatest Invention of the Civil War (Kent, OH: Kent State University, 2018), 35.

[10] ORN, 1, 6, 515; ORN, 1, 6, 517.

[11] ORN, 1, 6, 538.

[12] ORN, 1, 6, 771.

[13] John V. Quarstein, The CSS Virginia, Sink Before Surrender (Charleston, SC: The History Press), 86.

[14] ORN, 1, 6, 777.

[15] Franklin Buchanan to J. Bankhead Magruder, March 2, 1862, in Quarstein, The CSS Virginia, 104.

[16] United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Vol. 9 (Washington: GPO, 1883), 50.

[17] ORN, 1, 6, 780–81.

[18] Quartstein, The CSS Virginia, 110.

[19] Quarstein, John V. The Battle of the Ironclads (United Kingdom: Arcadia, 1999), 51.

[20] David A. Mindell, “‘The Clangor of That Blacksmith’s Fray’: Technology, War, and Experience Aboard the USS Monitor,” Technology and Culture 36, no. 2 (1995): 256.

[21] Quarstein, The CSS Virginia, 117.

[22] ORN, 1, 7, 8.

[23] ORN, 1, 7, 45.

[24] ORN, 1, 7, 42.

[25] ORN, 1, 7, 8.

[26] ORN, 1, 7, 45.

[27] Mark L. Evans, “Minnesota I (Frigate),” Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS), 10 August 2015.

[28] ORN, 1, 7, 8.

[29] ORN, 1, 7, 8.

[30] Quarstein, The CSS Virginia, 167.

[31] Lt. Samuel Dana Greene, Eye-Witness Account of the Battle Between the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Virginia Mar 9 1862, Naval Historical Foundation, last modified 12 September 2017.

[32] ORA, 1, 9, 27.

[33] ORA, 1, 9, 27.

[34] ORN, 1, 7, 758.

[35] ORN, 1, 7, 224.

[36] ORN, 1, 7, 228.

[37]ORN, 1, 7, 225.