Enterprise VII (CV-6)

1938–1956

Named to commemorate the previous six U.S. Navy ships named Enterprise.

VII

(CV-6: displacement 19,800; length 809'6"; beam 83'1"; extreme width 114'; draft 28'; speed 33 knots; complement 2,919; armament 8 5-inch; aircraft 80; class Yorktown)

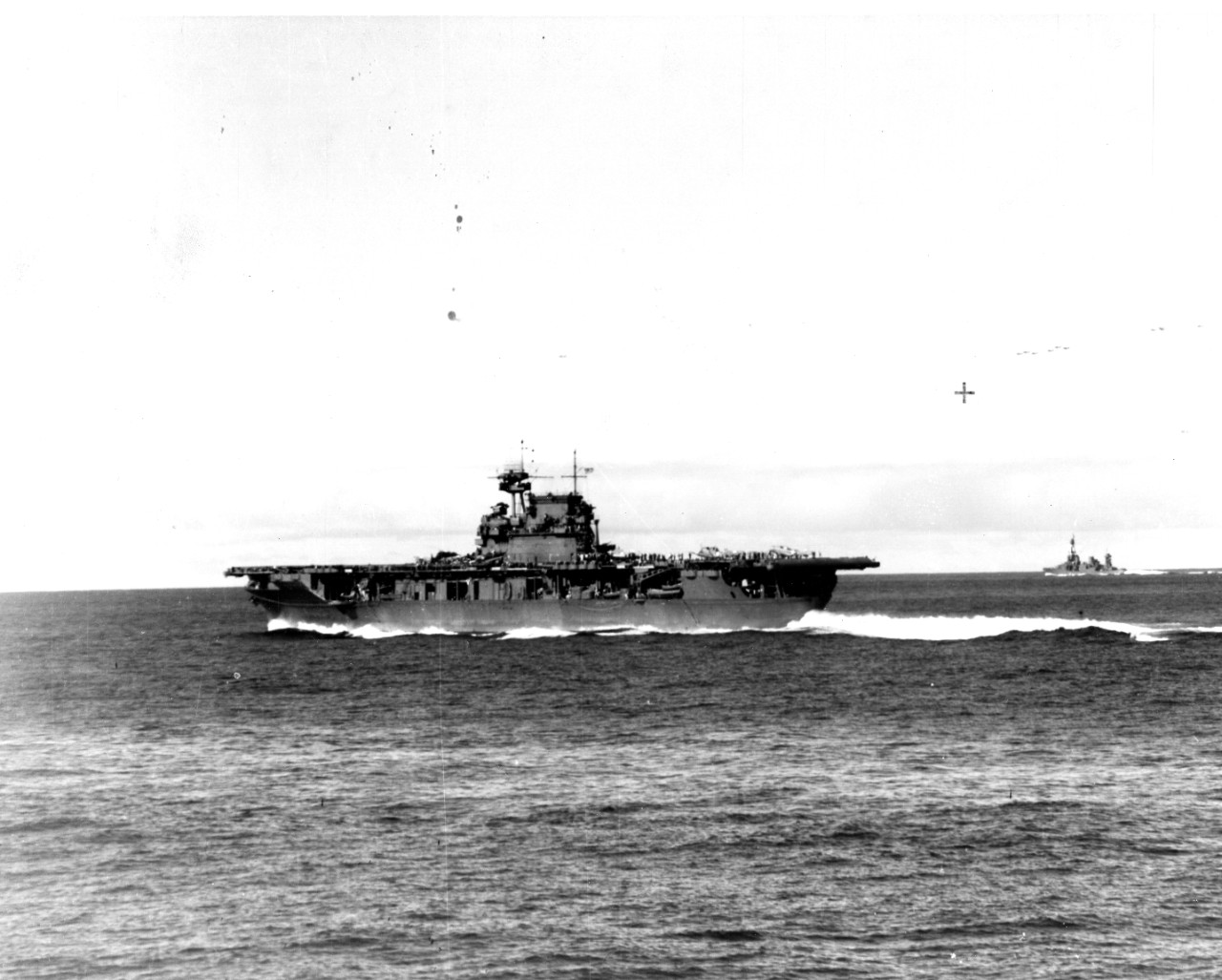

The seventh Enterprise (CV-6) was authorized by an Act of Congress on 16 June 1933; laid down on 16 July 1934, at Newport News, Va., by Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co.; launched on 3 October 1936; sponsored by Mrs. Lulie H. Swanson, wife of Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson; and commissioned on 12 May 1938 at Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk, Va., Capt. Newton H. White in command.

Under the terms of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, on 16 June 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt allotted $238 million to the Navy for the construction of new ships including two aircraft carriers, and in less than two months contracts were awarded for Carrier Nos. 5 and 6. Rear Adm. Ernest J. King, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), recommended the name Enterprise for Carrier No. 6 to Secretary of the Navy Swanson, on 11 August 1933:

“This is one of the most famous names of the Navy through its association in the French, Revolutionary and Tripolitan wars. It dates back to the Revolutionary War, when it was borne by one of [Benedict] Arnold’s vessels on Lake Champlain and later by a packet in the continental service on the Atlantic.”

The Navy subsequently selected the names Yorktown and Enterprise for Carrier Nos. 5 and 6, respectively. Rear Adm. William D. Leahy, Chief of the Bureau of Navigation (BuNav), endorsed the selection of the name Enterprise for the ship’s name plate on 27 September 1934: “to perpetuate the name borne” by the previous “fighting vessels of the United States Navy” named Enterprise. Swanson meanwhile invited First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to act as the ship’s sponsor, on 11 September 1934. On 12 February 1936, however, Rear Adm. Adolphus Andrews, BuNav, cancelled the directive and named Lulie H. Swanson, the secretary’s wife, to sponsor Enterprise, and the First Lady consequently sponsored Yorktown (CV-5). A BuAer request formalized plans to install hydraulic flush deck catapults on board carriers on 15 November 1934, in that space was to be reserved on board Enterprise and Yorktown for two bow catapults (each) on their flight decks, and one athwartships on their hangar decks. The distinguished visitors who attended the ship’s launching included: Lulie H. Swanson; Edith Wilson, widow of the late President Woodrow Wilson; Martha R. Fletcher, wife of Capt. Frank J. Fletcher, who commanded battleship New Mexico (BB-40), and Mrs. A.C. Young, who served as Swanson’s matron of honor.

Following the ship’s commissioning she worked up to join the fleet and loaded her initial planes. BuAer Newsletter No. 78 of 15 July 1938, recorded the “auspicious moment” at 1114 on 15 June, when Lt. Cmdr. Alan P. Flagg, the ship’s air officer, flew Plane No. 1, a Vought O3U-2 (BuNo. 9312), off the ship for her first take off, circled around, and two minutes later returned and made the first landing. “Incidentally,” the writer elaborated, “the promoter of a championship fight in the Yankee Stadium would have eyed with envy the array of spectators massed on the island superstructure.” The carrier continued with Plane Nos 1, 2, and 3 to qualify their pilots for flight operations on board but incurred her first accident. Flagg turned Plane No. 1 over to ACMM J.C. Clarke and AMM2c P.W. Petot, who launched and at 1130 attempted to land. Clarke failed to answer a frantic “low” signal from the landing signal officer (LSO) properly, however, throttled up to full power to rise to the level of the flight deck in answer to the LSO’s “wave off” signal, and the airplane’s fuselage and tail wheel struck the ramp. The pilot closed the throttle and the arresting gear stopped the Vought, and although the two crewmen escaped unscathed, their aircraft required considerable repairs.

Enterprise reported 81 planes on board on 30 June 1938: 20 Grumman F3F-2s, two O3U-3s, and one Curtiss SBC-3 of Fighting Squadron (VF) 6; 13 Northrop BT-1s of Bombing Squadron (VB) 6; 20 Curtiss SBC-3s of Scouting Squadron (VS) 6; and 20 Douglas TBD-1s of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 6. In addition, her Utility Unit comprised two more O3U-3s, two Grumman J2F-1s, and a TBD-1. BuAer authorized the squadrons to number 18 aircraft each but their strength fluctuated because of accidents or maintenance, and, they furthermore often operated one or two liaison planes. On 1 July the Navy organized carrier squadrons into groups, each designated by the name of the ships to which they were assigned.

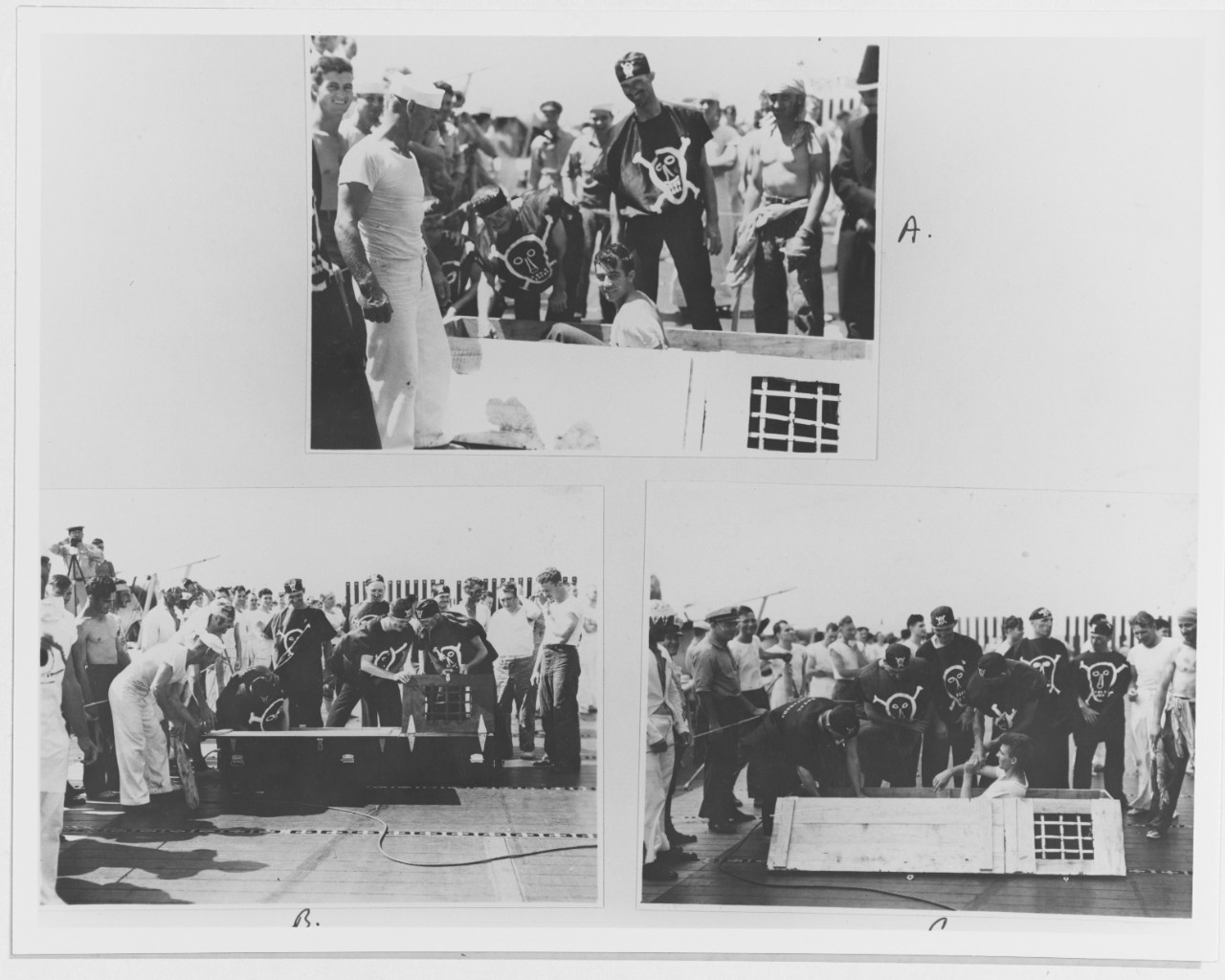

Enterprise unmoored from Pier 7 at NOB Norfolk and turned her prow southward for the ship’s shakedown cruise (18 July–22 September 1938). The carrier anchored off Ponce, P.R., on 23 July, on 27 July at Gonaïves Bay, Haiti, and in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (31 July–12 August). Enterprise briefly stood out of that harbor on 10 August, reversed heading and placed her stern into the wind, and backed as necessary to land planes over the bow before returning to the anchorage. Enterprise crossed the equator for the first time on 20 August, and then (25 August–3 September) called on Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She came about for home, stopped for mail at Guantánamo Bay (14–17 September), and a storm pounded the ship as she steamed northward off Cape Hatteras, before returning to Norfolk and completing voyage repairs. Enterprise battled through heavy seas while completing her final trials in New England waters (29 October–3 November), anchored in Cape Cod Bay south of Provincetown, Mass., on the day before Halloween, visited Boston, Mass. (31 October–1 November), and then returned to Norfolk. Capt. White fell ill and required treatment at Naval Hospital Norfolk, and Cmdr. James C. Monfort, the executive officer, temporarily commanded the ship (5–7 December). White continued to suffer, however, and Capt. Charles A. Pownall consequently relieved him in command of Enterprise on 21 December 1938. White was transferred to the retired list on 1 April 1939, but briefly returned to the colors during World War II.

Post-commissioning repair work delayed her full operational status with the fleet until the following year. Enterprise and Yorktown took part in a series of exercises in the New Year (4 January–12 April 1939). They practiced protecting a convoy during a voyage to the Caribbean, and Enterprise anchored at St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands on 8 January, Guantánamo Bay on 16 January, on 19 January at Gonaïves Bay, where the two carriers joined Aircraft, Battle Force, Carrier Division 2, and Enterprise anchored again at Guantánamo on 30 January. Enterprise and Yorktown then participated in Fleet Problem XX. The annual fleet problems concentrated the Navy’s power to conduct maneuvers on the largest scale and under the most realistic conditions attainable. Fleet Problem XX ranged across the Caribbean and the northeast coast of South America (20–27 February). President Roosevelt observed the problem initially from on board heavy cruiser Houston (CA-30), transferred to Pennsylvania (BB-38), and then returned to Houston to watch the final exercises, and the chief executive’s presence led to the maneuvers becoming unusually publicized.

Enterprise and Yorktown were so new that the referees limited them to operating their air groups during good weather and in daylight. The opponents divided into two fleets, Black and White. Vice Adm. Andrews, Commander Scouting Force, U.S. Fleet, led the Black Fleet, which comprised six battleships, Ranger (CV-4), eight heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, 32 destroyers, 15 auxiliaries, and five aircraft tenders. Vice Adm. Edward C. Kalbfus, Commander Battle Force, U.S. Fleet, took the White Fleet to sea, which also counted six battleships, as well as Enterprise, Lexington (CV-2), and Yorktown -- Vice Adm. King led the carriers -- six heavy cruisers, a half dozen light cruisers, 29 destroyers, 12 submarines, and target ship Utah (AG-16) as a surrogate for a trio of large troop ships. The opponents roughly balanced each other in numbers and types of ships, but the White Fleet counted more submarines and the fleets deployed different air strength. The Black Fleet contained only 72 carrier planes but nearly 60 floatplanes embarked on board the battleships and cruisers, 102 patrol planes supported by the tenders in (apparently) safe harbors, and 62 marine planes flying from ashore, and thus deployed stronger reconnaissance and scouting strength. The White Fleet deployed about 220 carrier aircraft and approximately 48 floatplanes on board the battleships and cruisers, and was thus stronger in carrier strength. A “Second Fleet” theoretically supported the White Fleet from an advanced base south of the Azores Islands.

The problem included: employing planes and carriers in connection with escorting a convoy; developing coordinating antisubmarine measures between aircraft and destroyers; and experimenting with various evasive tactics against attacking planes and submarines. Both of the admirals focused on their foe’s air power but in different ways — Andrews attempted to destroy the White Fleet, and Kalbfus used the convoy he was to protect as bait to lure the White Fleet into battle. Rough seas and infrequent rain squalls impeded both sides as they searched for each other on 21 February. Airplanes from Enterprise and Yorktown nonetheless spotted some Black cruisers but they flew under orders to search for Ranger and ignored the enemy ships. A trio of Black heavy cruisers thus slipped past the aircraft and attacked the convoy. Three escorting White heavy cruisers returned the 8-inch salvoes ineffectually, until 72 planes from Yorktown failed to spot Ranger, came about, and pounced on the enemy and sank two of the Black cruisers. The third ship, Salt Lake City (CA-25), attempted to escape only to be sunk by White cruisers. Aircraft from Enterprise and Lexington then discovered and sank two Black light cruisers and damaged another pair.

White destroyers Drayton (DD-366) and Flusser (DD-368) slid past Black’s sentinel Hopkins (DD-249) into supposedly secure Culebra, P.R., during the mid watch on 23 February, sank small seaplane tenders Lapwing (AVP-1) and Sandpiper (AVP-9), shot up some of the patrol planes moored in the harbor, and escaped. The ruse achieved stunning results, but in an effort to economize force, they attempted the same raid at San Juan that morning but the alerted enemy sank both ships. On the morning of 24 February, King directed Enterprise to attack the Black airfields and aircraft tenders and Lexington to find and sink Ranger. The plans including switching the fighters from Enterprise to Lexington and the latter’s scout bombers to the former, a rarely practiced evolution that provided each ship with a specialized air group. Before the carriers could accomplish their novel tactics, however, Black patrol planes flying from Culebra discovered them. Consolidated PBY flying boats operating out of San Juan and Samana Bay in the Dominican Republic attacked, but the pilots chattered over their radios in the clear and Enterprise and Lexington maneuvered out of harm’s way. Later that day, Capt. Marc A. Mitscher led additional PBYs against the carriers, and although he claimed to knock out Lexington, the umpires ruled that she took only light damage, and that her F3F-1s of VF-3 flying Combat Air Patrol (CAP) and antiaircraft guns exacted a costly toll.

Enterprise reached a position 120 miles north of San Juan during the morning watch on 25 February, and launched devastating strikes against Black airfields and ships, sinking seaplane tender Langley (AV-3) and an oiler at Samana Bay, and Wright (AV-1) and another oiler at San Juan. The victory raised the total score to four of the Black Fleet’s five aircraft tenders, and the ship achieved another success when TBD-1s of VT-6 flying from Enterprise discovered the enemy’s main body. The airplanes then began searching for Ranger, which steamed approximately 100 miles from the main body, but Ranger used an experimental high-frequency direction finding system and detected Enterprise, and threw Vought SB2U-1s of VB-3 and Vought SBU-1s of VS-41 and VS-42 that, in barely two hours smothered the ship’s defenses and sent her to the bottom. The exercises wrapped-up as men of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines made an opposed landing in Puerto Rico to gain an advanced base for the White Fleet.

King criticized Enterprise’s poor performance, which he attributed to her inexperienced air group. Evaluators also noted that the carriers did not embark enough fighters to simultaneously defend the ships and escort strike groups, and recommended raising VF strength above 18 planes per fighting squadron. The Navy did not adopt the recommendation, however, and rued the cost during the earlier battles of World War II. Controversy also arose over the efficacy of patrol plane attacks on carriers and other ships, and that the principal that patrol aircraft were to operate as scouts required emphasis. In addition, evaluators recommended the necessity of fast battleships to supplement cruisers in carrier task forces. Enterprise and Yorktown afterward visited Fort-de-France, Martinique (6–9 March).

Four carriers operated together as Enterprise joined Lexington, Ranger, and Yorktown for a fleet review off Hampton Roads, Va., on 12 April 1939. The ships were to spend a couple of weeks working up, pass in review on 27 April, and then steam to New York City to take part in the opening of the World’s Fair at the end of the month. Global events threatened stability, however, as the Germans and Italians moved toward war in Europe and the Japanese continued to attack the Chinese, and Enterprise was consequently ordered to the Pacific Fleet. The ship set out on 20 April, anchored in Limon Bay off Colón at the Panama Canal Zone on 26 April, the following day passed through the canal, anchored at Balboa for repairs and maintenance, resumed her cruise on 2 May, and on 12 May reached her new home port of San Diego, Calif. The planes of her air group moved ashore to Naval Air Station (NAS) San Diego on North Island.

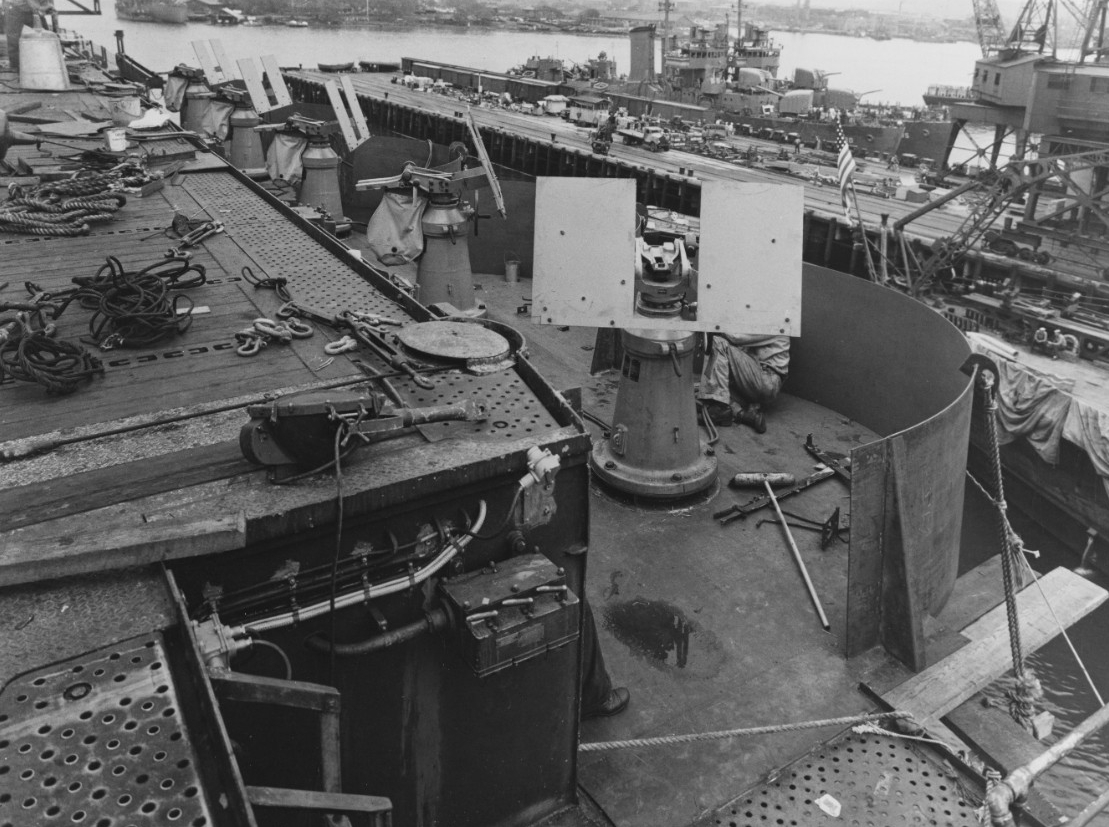

Enterprise became involved in introducing radar to the fleet. Adm. Leahy, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), held a policy conference on 1 May 1939 to reach decisions concerning the manufacture and installation of radar equipment. Based upon reports, Leahy and the attendees recommended procuring 20 copies of the experimental XAF radar. The Bureau of Engineering demurred because researchers sought to further improve the system, so the planners compromised and the Navy contracted for ten sets. The service disclosed details of the XAF to engineers at Western Electric Co. Laboratories on 18 May, and the following day to engineers at Radio Corp. of America (RCA). Officers and engineers presented the complete specifications for what they called “radio range equipment” for the prospective bids by the two companies prior to 15 June, but in lieu of contracting for the initial 20 sets, the bureau decided to purchase only six and contracted for them with RCA in October 1939, with the understanding that the Naval Research Laboratory would assist. The XAF was delivered to the contractor the following month, and, designated CXAM-1, delivered to the fleet and fitted in California, Yorktown, and Chicago (CA-29), Northampton (CA-26), and Pensacola (CA-24) (May–August 1940), and subsequently in Enterprise. Despite insufficient funding, those researchers succeeded in developing a detection system that eventually revolutionized naval warfare.

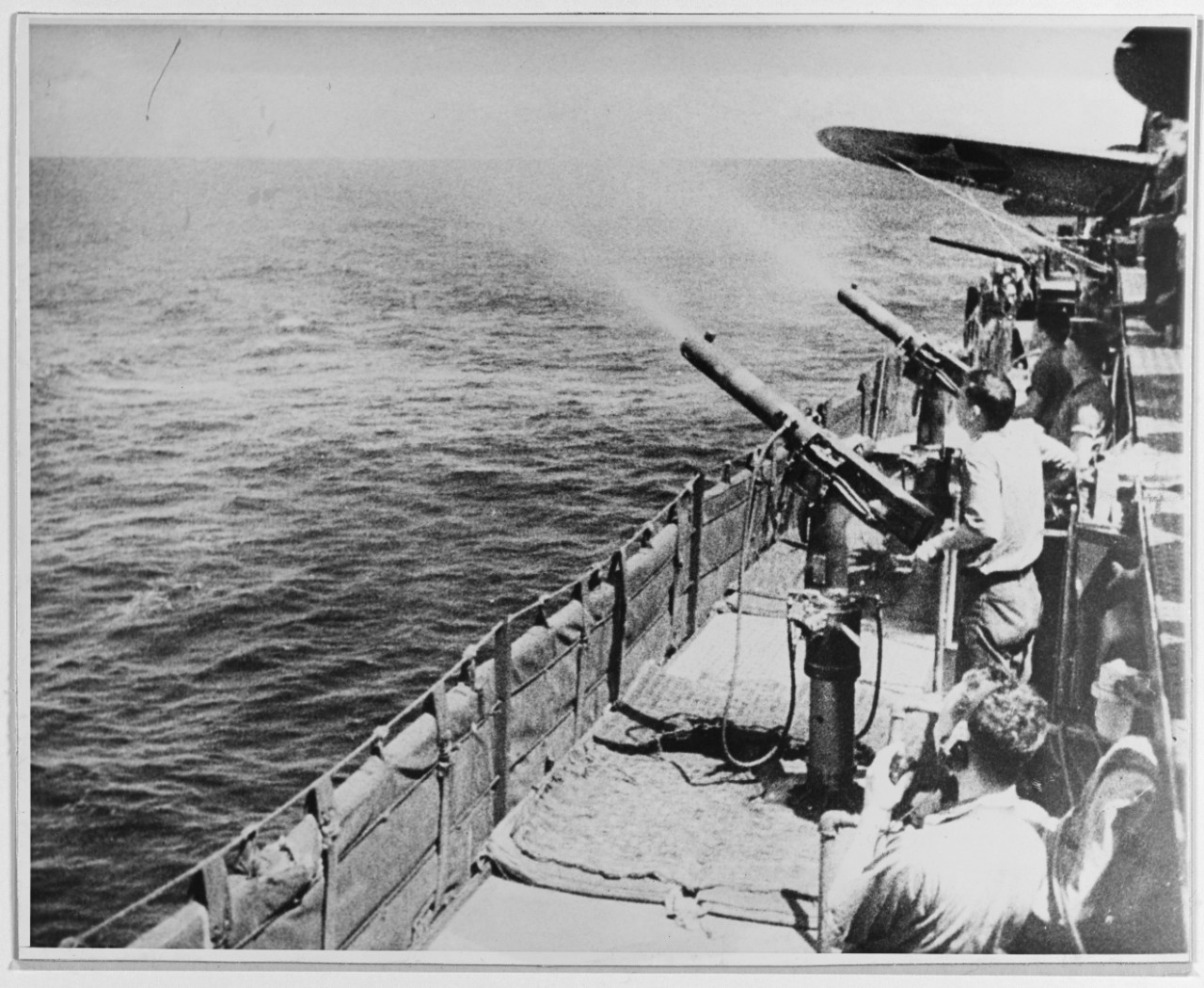

Enterprise conducted exercises in southern Californian waters during much of the summer but rarely put to sea for more than a day at a time. Lt. Cmdr. Richard F. Whitehead relieved Short in command of the Enterprise Air Group on 26 June 1939. The carrier celebrated Independence Day at San Francisco, Calif., along with the Golden Gate International Exposition, which commemorated the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, and was held at Treasure Island. Enterprise and Yorktown launched SBC-3s and O3U-3s from flight deck and hangar deck catapults on 4 August. Their action marked the first practical demonstration of launching planes from carriers by means of hydraulic flush-deck catapults, and provided the first evaluations of catapulting aircraft from hangar decks. Installing a catapult on the hangar deck enabled the ships to launch fighters or scout airplanes when aircraft fouled the flight deck. While Adm. James O. Richardson, Commander Battle Force, U.S. Fleet, led tactical exercises in the Pacific the following month, he deployed Enterprise and a pair of destroyers acting as plane guards at the center of a fleet formation. Four battleships, seven cruisers, and 18 destroyers steaming in three concentric circular patterns at one mile ranges protected the ship with their antiaircraft guns. “I believe that this was the first time” Richardson recalled, “that both of the following occurred: (1) the carrier occupied the key spot in a cruising formation [and] (2) all anti-aircraft resources of the formation were disposed for the protection of the carrier.”

The Navy expanded its presence at Pearl Harbor, T.H., in order to counter Japanese aggression during the Second Sino-Japanese War, and established the Hawaiian Detachment, U.S. Fleet, on 28 September. The measure included Enterprise and Vice Adm. Andrews, Commander Scouting Force, assumed command of the Hawaiian Detachment, broke his flag in Indianapolis (CA-35), on 30 September, and on 3 October shifted to Enterprise. In addition to the carrier, the force consisted of two heavy cruiser divisions, two destroyer squadrons and a light cruiser flagship, a destroyer tender, and a proportionate number of small auxiliaries, which sailed for Pearl Harbor (5–12 October 1939). The following month the detachment carried out exercises in Hawaiian waters.

Enterprise briefly (5–9 January 1940) steamed to Hilo, Hawaii, where she anchored on 7 January. The ship trained off Oahu for (30 January–1 February), and the following day was released from the detachment and set out for the west coast, arriving at San Diego on 9 February. Enterprise completed an overhaul at Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash. (21 February–28 May — carrying out the work from 25 February–24 May). She thus missed Fleet Problem XXI (1 April–17 May), which consisted of two separate phases around the Hawaiian Islands and Eastern Pacific. Enterprise moored at NAS San Diego on 28 May, but on that date Capt. Robert P. Molton Jr., who commanded Saratoga (CV-3), died. The following day Capt. Archibald H. Douglas relieved Capt. Pownall in command of Enterprise as scheduled, but after only a few hours (1504–1904) of leading Enterprise, Pownall resumed command of Enterprise, and Douglas accordingly detached and subsequently assumed command of Saratoga. Also on that busy day, Lt. Cmdr. Edward C. Ewen relieved Whitehead as the air group’s commander.

“As [Enterprise] pitched and rolled arthritically in the freshening seas,” Theodore C. Mason, a radioman on board California (BB-44), recalled during a voyage to Californian waters, “the flattop reminded me of a huge but decrepit old man with an entourage of bodyguards. If some seer had told me then that the Enterprise would steam to glory on one of the most brilliant combat records of any ship in the history of the navy, I would have given him the pitying smile one reserves for fools. From where I stood, it looked like she might have trouble reaching the West Coast.”

The weathered ship returned to sea from North Island during a voyage to Pearl Harbor (25 June–2 July 1940). Enterprise anchored at Lāhainā Roads at Maui, T.H., on 9 July, and on 13 July at Honolulu, where she embarked people from Warner Bros. and took part in the motion picture Dive Bomber, starring Errol Flynn, Fred MacMurray, Ralph Bellamy, Alexis Smith, and Regis Toomey, released in August 1941. Enterprise steamed at sea for two days of filming (16–17 July), and her crew enthusiastically supported the effort, her deck log noting wryly on the second day: “Making movies, no absentees.” Two clips show a plane landing on and taking off from the ship, a rarity in motion pictures at the time, and a number of her crewmen who took part in the filming of Dive Bomber served in her during World War II. The ship disembarked her passengers at Honolulu on 19 July, and on 26 July moored at Pearl Harbor. Film crews subsequently shot additional footage at NAS San Diego.

Enterprise resumed training in Hawaiian waters, anchored at Lāhainā Roads on 20 August, on 28 August at Honolulu, and moored at Pearl Harbor on the last day of the month. During one of those exercises (8–14 September), Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox broke his flag in Enterprise to observe maneuvers. Adm. Richardson, now Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, also broke his flag in the carrier for a trial period. Knox briefly transferred to light cruiser Boise (CL-47) on 9 September but returned to the carrier. On 13 September Lt. Cmdr. Ewen flew Knox as a passenger in an SBC-4 to NAS Pearl Harbor on Ford Island to emphasize the rapid pace of modern naval operations. Enterprise anchored at Honolulu on 14 September and then moored at Pearl Harbor, anchored at Lāhainā on Halloween, and on 2 November returned to Pearl Harbor. The ship steamed to San Diego (9 November–2 December — she reached North Island on 14 November), and ended the year by completing degaussing and antiaircraft installations at Puget Sound (2–31 December 1940).

The global crisis compelled the service to cancel Fleet Problem XXII, originally scheduled for January 1941. “In view of the international situation,” Adm. Harold R. Stark, CNO, wrote to Gen. George C. Marshall Jr., USA, the Army’s Chief of Staff, on 3 December 1940, “plans for Fleet Problem XXII have been cancelled.” President Roosevelt’s attendance had attracted considerable notoriety to the exercises; loose lips talked, and the front page of the New York Times New Year’s edition announced: “ALL NAVY GAMES OFF FOR THIS YEAR.” “SHIPS IN FIGHTING TRIM”, the newspaper further observed, but elaborated that the fleet was to be held in “Hawaiian waters, and, according to good information, will remain there until the existing international situation is definitely improved.”

Enterprise in the meantime renewed her busy cycle of training and upkeep and anchored at Coronado, Calif., on 2 January 1941, the following day at San Diego, steamed to San Pedro, near Los Angeles and Long Beach, and then (13–21 January) sailed back to Pearl Harbor. The ship set out for an unusual ferry cruise for NAS San Diego (7–13 February), where she loaded 30 USAAC Curtiss P-36A Hawks that were to operate from Wheeler Field on Oahu, T.H. Enterprise returned to sea two days later and on 21 February arrived about 200 miles off Oahu and launched the Hawks. On 20 February meanwhile, Adm. Stark directed the Puget Sound Navy Yard regarding the priority of ships then under construction and repair based “on the operative requirements of the Fleet.” Stark’s missive noted that Enterprise was to be assigned a restricted availability for an interim overhaul, to begin on 3 March and to have her ready again for sea by the end of the month. Enterprise consequently crossed the eastern Pacific (23 February–3 March) and through the end of the month moored at Bremerton and completed the work, which included degaussing and splinter protection.

The warship then (31 March–3 April) made for North Island, and Lt. Cmdr. Howard L. Young relieved Ewen as Commander Enterprise Air Group on 19 April. The carrier repeatedly cast off her mooring lines and worked up during voyages between San Diego and Pearl Harbor (21–27 April, 29 April–4 May, and 8–13 May), and during the next few months (21 May–2 June, 10–18 June, 30 June–8 July, 24 July–1 August, 14–22 and 27–30 August, 4–12 September, 24 September–2 October, 18–26 October, and 9–17 November) took part in maneuvers primarily in Hawaiian waters. Under Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal led an entourage on board the ship that included Rear Adm. John H. Towers, BuAer, and John F. Dulles (29–30 July).

Balch (DD-363) brought Lord (Capt.) Louis Mountbatten, RN, on board Enterprise on 25 September while the British officer toured the Hawaiian Islands. The training sometimes proved lethal and Enterprise lost a Douglas SBD-2 (BuNo. 2149), manned by Lt. Thomas Ainsworth Jr. and RM1c C.J. Schlegal of VB-6 on 21 October. The sea was smooth but the horizon extremely dark as the Dauntless attempted to land but missed the flight deck, crashed into the starboard walkway, and went over the side. Ainsworth died, and Schlegal was rescued but suffered a laceration to his scalp, a contusion of the left orbit, and multiple abrasions of his lower extremities. Tensions between the Japanese and Allies rose and the ship reported suspicious vessels: a “small boat” on the morning of 22 October that turned out to be a fishing sampan; a darkened vessel that sailed with a single small white light on 12 November; and another sampan on 16 November — the boats continued on their way.

As the war clouds loomed on 30 November 1941, Enterprise reported that she normally embarked: 17 Grumman F4F-3A Wildcats and two F4F-3s of VF-6; 10 SBD-2 and eight SBD-3 Dauntlesses of VS-6; 19 SBD-2s of VB-6; and 18 TBD-1 Devastators -- and at times two North American SNJ-3 Texans – of VT-6. In addition, Cmdr. Young flew an SBD-2; and two Curtiss SOC-2 Seagulls and a pair of J2F-2 Ducks comprised the ship’s Utility Unit. The carrier also listed two F4F-3s, three SBD-2s and one SBD-3, and five TBD-1s in storage.

When Japanese aggression had increasingly threatened the Pacific Rim in 1938, a committee under Rear Adm. Arthur J. Hepburn, then commandant of the Twelfth Naval District, had investigated possible naval base sites on the coasts of the United States, its territories, and possessions. The Hepburn Board, as it became known, ranked Wake Island as a strategically vital bastion, and recommended expanding the defenses there. As the U.S. prepared for war in the summer and autumn of 1941, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet, decided that operational and logistics issues precluded deploying Army planes to Wake, and decided to operate USN and USMC aircraft from the islands in their stead. Consequently in November 1941, Marine Fighting Squadron (VMF) 211, Maj. Paul A. Putnam, USMC, in command, received orders to augment Wake Island’s defenses. Wright put in to Pearl Harbor and embarked Cmdr. Winfield S. Cunningham, who was to take command of the naval activities on Wake Island, together with asphalt technicians, other construction workers, and Marine Corps officers (20 November–8 December). The ship also carried 63,000 gallons of gasoline for the island’s storage tanks, and after touching at Wake, Wright shaped a course for Midway, where she delivered a cargo that included ammunition and disembarked passengers.

Kimmel selected Task Force (TF) 8, Vice Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., in command and formed around Enterprise, to deliver the 12 marine F4F-3s to Wake Island. Kimmel and some of the Pacific Fleet planners, however, believed that Japanese spies ensconced within their consulate reported U.S. ship movements, and thus temporarily reinforced the carrier with battleships and their escorts as TF 2, in order to give the illusion of a routine exercise. Events in the meantime escalated to war, and Adm. Stark sent a “War Warning” message to the commanders of the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets on 27 November 1941, a day after Japanese Dai-ichi Kidō Butai (the 1st Mobile Striking Force), Vice Adm. Nagumo Chūichi in command, sailed from Japanese waters to attack Oahu. Putnam had known of VMF-211’s impending departure, but because of the exigencies of the situation the squadron received orders to deploy swiftly, and the men carried only limited clothes and toilet articles. The following morning, they flew their planes from Ewa Mooring Mast to NAS Pearl Harbor, and from there out to the ship. One of the Wildcats developed starter trouble and remained behind on Ford Island, so the squadron only flew 11 on board; and VF-6 reassigned one of its airplanes (BuNo. 3988), which served as Marine 211-F-9. Enterprise, Arizona (BB-39), Nevada (BB-36), and Oklahoma (BB-37), screened by cruisers and destroyers, meanwhile stood down the channel from Pearl Harbor. Halsey then detached Enterprise and in company with Chester (CA-27), Northampton, and Salt Lake City, together with Balch, Benham (DD-397), Craven (DD-382), Dunlap (DD-384), Ellet (DD-398), Fanning (DD-385), Gridley (DD-380), Maury (DD-401) and McCall (DD-400), set out for Wake, “Fully expect[ing] that the trip with these Marines was leading us into the lion’s mouth.” The admiral approved Battle Order No. 1, issued by Capt. George D. Murray, the carrier’s commanding officer:

1. The Enterprise is now operating under war conditions.

2. At any time, day or night, we must be ready for instant action.

3. Hostile submarines may be encountered.

4. The importance of every officer and man being specially alert and vigilant while on watch at his battle station must be fully realized by all hands.

5. The failure of one man to carry out his assigned task promptly, particularly the lookouts, those manning batteries, and all those on watch on deck might result in great loss of life and even loss of the ship.

6. The Captain is confident all hands will prove equal to any emergency that may develop.

7. It is part of the tradition of our Navy that, when put to the test, all hands keep cool, keep their heads, and FIGHT.

8. Steady nerves and stout hearts are needed now.

Halsey also ordered radio silence and for the maintainers to fuel planes, fit warheads to torpedoes, and to prepare bombs for loading. Enterprise launched daily fighter CAP and search patrols out to nearly 200 miles ahead of the ship’s course. PBY Catalinas flew supporting patrols from advanced bases at Wake and Midway, and submarines patrolled the waters around those isles. Enterprise steamed in darkened condition overnight on 4 December, and during the morning watch a PBY-3 of Patrol Squadron (VP) 22 rendezvoused with the ship about 200 miles from Wake. The Catalina orbited while the marine Wildcats rumbled off the ship’s flight deck (0656–0707), and then led the fighters to the island. The carrier came about for Hawaiian waters, and a routine scouting flight from the ship later that day sighted Honolulu-bound tug Sonoma (AT-12), with Pan American Airways barges PAB No. 2 and PAB No. 4 in tow. Sonoma sailed from Wake Island on 26 November, and eventually reached Honolulu with her tows on 15 December. The carrier’s mission, meanwhile, and heavy seas (5–6 December), delayed her return from the afternoon of 6 December to the following morning, and thus ensured that the ship eluded the Japanese attack on Oahu on 7 December.

On that fateful day Enterprise arrived off Oahu about 200 miles west of Pearl Harbor, and began launching planes during the morning. At 0618 Young flew Lt. Cmdr. Bromfield B. Nichol, Halsey’s flag secretary, ashore so that he could report on the Wake Island mission to Kimmel — a second bomber flew wing. The ship then launched a routine search flight of 13 SBD 2s and 3s of VS-6 and four SBD-2s from VB-6 in two-plane sections. The Dauntlesses began reaching land as the Japanese attack unfolded, and their crews spotted aircraft flying over Ewa and the telltale puffs of antiaircraft fire. Some of the men believed that they arrived in the midst of a surprise drill and wondered how they would land through the shell bursts, and then Japanese pilots sighted and attacked the Enterprise planes. Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 carrier fighters pounced on 6-S-15, an SBD-2 (BuNo. 2159), Ens. Walter M. Willis, USNR, and Coxswain Fred J. Ducolon of VS-6, and shot it down, and at least two other Enterprise planes attempted to fight the more maneuverable enemy fighters but were lost.

6-S-16, a Dauntless manned by Lt.(j.g.) Frank A. Patriarca and RM1c Joseph F. DeLuca, sighted the antiaircraft bursts and geysers of water erupt among the ships, and as the enemy fighters attacked, Patriarca dove for the coast-line at full throttle and escaped the more nimble Zeros and survived the fray and ended up on Kauai, where DeLuca was drafted into the local Army defense force with his single .30-caliber machine gun. Enemy planes attacked 6-S-4, Lt. (j.g.) Clarence E. Dickinson Jr., and RM1c William C. Miller of VS-6, and shot away his controls and started a fire in the airplane’s left tank. The Dauntless became uncontrollable and fell in a right spin and crashed. Dickinson parachuted to safety but Miller died. Just before Dickinson bailed out he looked aft and spotted a Japanese plane afire and losing altitude, and believed that Miller had splashed the Zero. Dickinson received the Navy Cross for continuing “to engage the enemy until his plane was forced down in flames,” and for then flying a search patrol because his harrowing ordeal had not “been reported to his superiors”.

Another Dauntless, 6-S-3 (BuNo. 2160), an SBD-2 manned by Ens. John H.L. Vogt and RM3c Sidney Pierce, collided with a Japanese Aichi D3A1 Type 99 carrier bomber, manned by PO2c Koreyoshi Sotoyama and Flyer 1c Hajime Murao, while the rivals maneuvered at low altitude. Both planes crashed quickly, and all four men died because their aircraft flew at low altitudes and they could not eject in time. “We saw one of these Enterprise airplanes and one Japanese airplane collide in the air,” Lt. Col. Claude A. Larkin, USMC, the commanding officer of Marine Aircraft Group 21 later testified, “Both of them fell and burned a half mile south and east of Ewa.”

At least one of the aircraft succumbed to ‘friendly fire’. “This is Six-Baker-Three, an American plane,” Ens. Manuel J. Gonzalez, USNR, who flew VB-6’s third SBD-2 Dauntless (BuNo. 2181), radioed desperately, “Don’t shoot!” Listeners overhead Gonzalez apparently tell RM3c Leonard J. Kozelek, his gunner: “Standby to get out the rubber boat”, followed by an ominous silence. The Japanese downed the airplane at sea and both men died, however, the bomber last reported near a position believed to be about 15 miles northwest of Oahu. Young and 6-S-2, a Dauntless flown by Ens. Perry L. Teaff and RM3c Edgar P. Jinks of VS-6, twisted and turned through enemy Zeros and antiaircraft fire and landed on Ford Island. A Dauntless splashed into the water off the Army’s Hickam Field, but both men survived. Bullet and antiaircraft shell fragment holes riddled a number of the surviving planes.

On board Enterprise at sea, meanwhile at 0812, Halsey received a message alerting him to the Japanese attack. Some of the men on board initially disbelieved the news, but as additional messages reached the ship she sounded general quarters, launched Wildcats to fly CAP, and readied the remaining bombers for a strike. Nagumo brought his carriers about following the raid and sailed from Hawaiian waters, but many Americans feared that the Japanese carriers might still be operating nearby. Almost all of the surviving Dauntlesses that flew ashore therefore, together with what observation and scouting planes from battleship and cruiser detachments, as well as flying boats and utility aircraft that survived the air raid, took part in desperate, hastily organized searches flown out of Ford Island to look for the Japanese carriers. Ens. Teaff flew one of these searches during the afternoon watch, despite his damaged plane’s defective engine. The pilot flew knowing that he possessed a slim chance of rescue in the event that he crashed, and later received the Navy Cross for “unhesitatingly” flying the perilous search. At least one Dauntless landed at Kaneohe Bay in spite of automobiles and construction equipment parked on the ramp to prevent such an occurrence.

A report claimed to sight some of the enemy ships south of Oahu, and toward dusk -- just before 1700 -- Enterprise launched a strike consisting of her 18 operational Devastators, a half dozen Dauntlesses fitted with smoke generators to screen the torpedo bombers with smoke, and six escorting Wildcats. The planes searched out to about 100 miles southeast of Enterprise but failed to sight any enemy ships, and then the bombers returned to the carrier and the Wildcats ashore. Enterprise thus accomplished the first U.S. naval night recovery during World War II when the ship turned-on her searchlights to aid the returning Devastators and Dauntlesses. The Wildcats approached Hickam Field at about 2100, but their appearance panicked many of the antiaircraft gunners in the area and guns opened fire, their stark flashes lighting the gathering darkness. The gunfire downed four of the F4F-3A Wildcats. Lt. (j.g.) Francis F. Hebel landed his riddled airplane, 6-F-1 (BuNo. 3906), near Wheeler Field but suffered a severe skull fracture and died the next day. 6-F-15 (BuNo. 3935), Ens. Herbert H. Menges, and 6-F-12 (BuNo. 3938), Lt. (j.g.) Eric Allen Jr., were also lost. Allen parachuted and splashed into the oily water near minesweeper Vireo (AM-52), but he received a bullet wound and suffered internal injuries and succumbed the following day. 6-F-4 (BuNo. 3909), Ens. David R. Flynn, apparently ran out of fuel and Flynn bailed out over a cane field near Barbers Point and survived. 6-F-5 (BuNo. 3916), Ens. James G. Daniels III, and 3-F-15 (BuNo. 3982 — on loan from VF-3), Ens. Gayle L. Hermann, landed on Ford Island.

The damage to the battle line proved extensive, but Enterprise, Lexington, and Saratoga (CV-3) providentially escaped, the former two ships having been deployed at the eleventh hour to reinforce Wake Island and Midway Island. TF 12, led by Rear Adm. John H. Newton and including Lexington, steamed 425 miles southeast of Midway to deliver 18 SB2U-3 Vindicators from Marine Scout Bombing Squadron (VMSB) 231 to the island when the Japanese struck. Lexington launched planes to search for the attackers, and then came about with the Vindicators still on board and made to the south toward a planned rendezvous with Enterprise about 120 miles west of Kauai. These ships then joined TF 3, Vice Adm. Wilson Brown Jr., who broke his flag in Indianapolis, and searched southwest of Oahu before returning on 13 December to Pearl Harbor. Saratoga had completed an overhaul and just reached San Diego.

Enterprise meanwhile ran low on fuel and six Wildcats flew protectively overhead as she entered Pearl Harbor as the sun set on 8 December. The Wildcats then reinforced Army pursuit planes ready to defend the island from further enemy attack. Enterprise moored amidst water covered by oil from the sunken ships, and while sailors attempted to rescue men trapped in ships that capsized during the attack. The air reeked of death and oil, and fires still burned from the stricken vessels and ashore, casting an eerie glow over the men as they worked to ready the ship for battle. Enterprise hastily refueled, lighters brought provisions alongside, and men rushed to load them on board. Halsey and Murray were anxious to avoid the fate of the ships struck during the attack, and took the carrier back to sea during the morning watch on 9 December.

The Japanese deployed submarines to shadow and attack U.S. ships in Hawaiian waters one of which, I-70, Cmdr. Sano Takao in command, lurked about four miles southwest of Diamond Head on 9 December when Sano reported a U.S. carrier “entering” Pearl Harbor as Enterprise slipped past and edged her way out to the Pacific. Another submarine, I-6, Cmdr. Inaba Tsuso, reported sighting a Lexington class carrier and two heavy cruisers north of Molokai and steaming northeast away from Oahu that day, and the two reports triggered a flurry of activity as the Japanese Sixth Fleet deployed submarines against the carriers.

Ens. Teaff flew an SBD-3 from Enterprise and sighted I-70 while the submarine steamed on the surface, about 121 miles northeast of Cape Halava, Molokai, on 10 December. The Dauntless dropped a bomb that splashed close aboard I-70 and damaged the boat, preventing her from submerging. Later that day Lt. (j.g.) Dickinson flew another Dauntless and sighted the Japanese in the waters north of the Hawaiian Islands, near 23°45'N, 155°35'W. Dickinson climbed to 5,000 feet and dived, but the Japanese spotted his aircraft and the boat turned to starboard, while her 13 millimeter machine gun fired at the diving Dauntless. The plane dropped a 1,000 pound bomb that exploded close aboard amidships, the blast throwing several of the submarine’s gunners overboard. I-70 stopped and sank on an even keel in barely a minute, becoming the first Japanese warship sunk by U.S. aircraft during the war. Dickinson turned and spotted at least four enemy sailors in the water struggling to stay afloat amidst oil and debris. The Japanese attempted to raise the submarine by radio but, when they failed to do so, classified I-70, Sano, and all 92 of his men lost. Dickinson received a Gold Star in lieu of a second award of the Navy Cross for his “outstanding courage, daring airmanship and devotion to duty.”

Enemy submarines stalked Enterprise and one fired a torpedo that churned past the ship while she maneuvered to recover planes at one point, and Salt Lake City shelled what her lookouts believed to be a surfaced submarine during an additional instance. Sailors sighted yet another torpedo as it raced past barely 20 yards astern of Enterprise at 0900 on 11 December, just missing the ship, and destroyers depth charged the intruder but she escaped. Overly zealous men reported nearly continual enemy operations and a progressively exasperated Halsey signaled his displeasure to the task force, adding caustically that “we are wasting too many depth charges on neutral fish.”

The ships company maintained radio silence yet overheard broadcasts, many inaccurate or prone to hyperbole, but when the marines repulsed a Japanese landing on Wake on 11 December, the news electrified the crew. The men of VF-6 in particular, who had hosted the marines during the voyage, felt pride in the Leathernecks’ valiant defense. TF 14, Rear Adm. Fletcher in command and including Saratoga, sailed from Pearl Harbor on 16 December, to relieve the garrison on Wake Island. The embarked reinforcements included 18 Brewster F2A 2 and 3 Buffaloes of VMF-221 on board Saratoga, and additional marines on board Tangier (AV-8). Vice Adm. Brown’s TF 11 intended to launch a diversionary raid on Jaluit Island, but revised intelligence persuaded Brown to first attack Makin Island in the Gilbert Islands [Kiribati], and then divert back to Wake to support the relief expedition.

Enterprise returned to Pearl Harbor on 17 December 1941, but Pacific Fleet planners strenuously attempted to ensure that only a single carrier entered Pearl Harbor at a time, and Halsey took Enterprise and TF 8 to sea on 19 December, and proceeded to the waters west of Johnston Island and south of Midway to cover TFs 11 and 14. Heavy seas damaged Craven soon after their departure and she returned to Pearl Harbor for repairs. The following day Dauntlesses of VB-6 and VS-6 flying from Enterprise accidentally bombed U.S. submarine Pompano (SS-181) twice but she escaped without serious damage, near 20°10'N, 165°28'W, and 20°15'N, 165°40'W, respectively. Meanwhile, Saratoga and Tangier encountered delays owing to the slower speed of oiler Neches (AO-5) and from Fletcher’s decision to refuel the destroyers, and the Japanese consequently overran Wake. Enterprise steamed more than 1,000 miles from Wake when the enemy overran the island, and the news of Wake’s fall saddened the crew and a gloom temporarily settled upon the ship. The relief expedition came about and returned to Pearl Harbor.

The Americans continued to dispatch reinforcements to fight the Japanese and four days before Christmas TF 17, Rear Adm. Frank J. Fletcher in command and built on Yorktown, passed through the Panama Canal from the Atlantic Fleet and joined the Pacific Fleet. During the last two weeks of December 1941, Enterprise patrolled to the westward of the Hawaiian Islands before returning to Pearl Harbor on New Year’s Eve 1941. The air group flew to Ewa and as a Wildcat (BuNo. 3907), Ens. John C. Kelley of VF-6, lifted off the plane dropped to port, stalled, and crashed into the sea. The impact thrust Kelley’s head into his gunsight mount, but he climbed free of the sinking fighter and a destroyer rescued him. Some of the Wildcat pilots shared beers with marines at Ewa while they remembered the men at Wake. They then flew to Ford Island, where, despite being restricted from liberty, appreciated catching-up on their sleep.

Enterprise trained in Hawaiian waters north of Oahu early in the New Year (3–7 January 1942), exercises plagued by heavy seas and poor antiaircraft gunnery that failed to impress the Wildcat pilots. The Americans possessed limited intelligence concerning Japanese forces in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, but while Dolphin (SS-169) carried out her first war patrol (24 December 1941–3 February 1942), the submarine reconnoitered some of those islands and reported them to be lightly defended. Her intelligence contributed to a plan to penetrate the Japanese defensive perimeter and raid the Gilberts and Marshalls. On 8 January Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet, decided to combine Halsey’s TF 8 and Fletcher’s TF 17 into a single task force, which subsequently became TF 16, and directed them to carry out the raid.

The Allies also had to protect the important lifeline to Australia, and Enterprise sailed on the morning of 11 January to help guard a convoy, consisting of transports Lurline, Matsonia, and Monterey, cargo ship Jupiter (AK-43), and ammunition ship Lassen (AE-3), that carried the 2nd Marine Brigade, Brig. Gen. Henry L. Larson, USMC, in command, to Pago Pago, Samoa. Japanese submarine I-6, however, detected Saratoga while she steamed about 500 miles southwest of Oahu that day, and at 1915 Inaba fired a deep-running torpedo into her port side amidships. Six men died, water poured into three firerooms, and the ship listed to port. Saratoga made for Oahu and then for repairs and modernization at Puget Sound, and her departure temporarily reduced U.S. fleet carrier strength in the Pacific to three ships, compelling the Navy to distribute her air group among the other carriers.

To protect Halsey’s advance for the strike on the Gilberts and Marshalls, PBY-5 Catalinas of VP-23 began daily searches of the waters between their temporary base at Canton Island and Suva in the Fijis on 16 January. At 1350 on that date, a TBD-1 (BuNo. 0335), AMMC Harold F. Dixon, a Naval Aviation Pilot, AOM2c Anthony J. Pastula, the bombardier, and RM3c Gene D. Aldrich, the gunner, of VT-6 took off from Enterprise for a routine search out to 175 miles in a 10° (relative) sector from the ship. A moderate breeze and scattered squalls touched the area, but the Devastator ran out of fuel and crashed at sea later that day. Dixon and his two crewmen scrambled into their raft, at one point beat off sharks with their bare fists, and subsisted on occasional fish speared with a pocket knife, two birds, and rain water during a 34 day journey to Pukapuka in the Cook Islands, where they made landfall on 19 February. The straight line distance of their voyage measured 450 miles, but their estimated track reached 1,200 miles. Dixon received the Navy Cross for his “extraordinary heroism, exceptional determination, resourcefulness, skilled seamanship, excellent judgment and highest quality of leadership” in this epic of survival. Yorktown in the meantime rendezvoused with and escorted the convoy during part of its voyage. The swifter transports detached on 19 January and steamed to Pago Pago, followed the next day by the slower vessels. Enterprise and Yorktown (separately) covered the convoy and then came about.

Halsey and Fletcher rendezvoused on 25 January 1942, and set course for the enemy-occupied Gilberts and Marshalls. Halsey organized the strike force into three task groups (TGs) and attacked on 1 February 1942, a Sunday. TG 8.5, comprising Enterprise, Blue (DD-387), McCall, and Ralph Talbot, struck Kwajalein, Maleolap, and Wotje. Rear Adm. Raymond A. Spruance commanded TG 8.1, consisting of Northampton, Salt Lake City, and Dunlap, and shelled Wotje. Capt. Thomas M. Shock led TG 8.3, numbering Chester (CA-27), Balch, and Maury, and bombarded Taroa in Maleolap Atoll. Vice Adm. Brown’s TF 11, including Lexington, supported the raid from the vicinity of Christmas Island. TF 17 struck Jaluit, Makin, and Mili, and Platte (AO-24) and Sabine (AO-25) refueled the ships of the task forces. Cmdr. Thomas P. Jeter, Enterprise’s executive officer, summarized the feelings of many of the men on board as he topped the ship’s plan of the day with a vengeful verse:

An eye for an eye,

A tooth for a tooth,

This Sunday it’s our turn to shoot.

—Remember Pearl Harbor.

Aircrews woke up at 0300 and hurriedly ate a special breakfast, the ship sounded flight quarters at 0345, and she then turned to her launch position. Enterprise sent 46 Dauntlesses and 18 Devastators in two waves (0445–0513). “With props turning and strong prop wash and the danger of whirling blades in crowded quarters,” Lt. Cmdr. Frank T. Corbin, the fighting squadron’s executive officer, afterward recalled the dangerous experience of leading his men across the packed flight deck to their planes, “the manning of airplanes was always like broken field running in a crouch.” Corbin triggered the first launches when he flew his Wildcat aloft into the darkness. Cmdr. Young led 37 Dauntlesses over Kwajalein, followed by nine Devastators armed with bombs for horizontal bombing. Despite the lack of actionable intelligence the Americans’ expected to face strong opposition over the strategically vital atoll, and gambled by splitting their fighters. Six Wildcats flew CAP over the ships, and the remaining 12 struck the defenders, which meant that the bombers flew their missions without fighter escorts. A Dauntless with engine trouble and the second wave of nine Devastators, also bomb-armed, delayed the final bomber launches until just after 0500, followed more than an hour later by the remaining Wildcats. 6-F-11, an F4F-3A (BuNo. 3937), Ens. David W. Criswell, USNR, suddenly veered violently to port as the pilot, who lacked night flying experience, possibly attempted to compensate for the indistinct horizon. The Wildcat stalled and flipped over onto its back, slid overboard with a resounding splash, and sank quickly, taking Criswell to the bottom. The ship launched additional Devastators into the forenoon watch, and then a hush fell upon many of the crewmen on board as they awaited the outcome.

The enemy garrison on Roi -- which the Japanese knew as Ruotta -- received a few minutes advanced warning and their antiaircraft guns opened fire as the American planes arrived overhead. 6-B-10, Lt. Richard H. Best and ACRM James F. Murray, dived through enemy fire more than once on the ships in the lagoon. The attackers sank transport Bordeaux Maru, and damaged light cruiser Katori, submarine depot ship Yasukuni Maru, I-23, minelayer Tokiwa, auxiliary netlayer Kashima Maru, auxiliary submarine chaser No. 2 Shonan Maru, oiler Toa Maru, tanker Hoyo Maru, and army cargo ship Shinhei Maru at Kwajelein. The aircraft that bombed the shore installations included a Dauntless that scored a direct hit on the headquarters of Rear Adm. Yatsushiro Sukeyoshi, Commander Sixth Base Force, killing the flag officer. Later that day enemy fighters riddled 6-B-10 with bullets, but Best and Murray resolutely pressed home their attack and bombed a hangar, and then made a second sweep and strafed the area to ensure that they destroyed the building. Best subsequently received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his actions. Aircraft also dropped leaflets containing a personal message from Halsey to the Japanese garrison that read (in Japanese): “It is a pleasure to thank you for having your patrol plane not sight my force.” Japanese submarines I-9, I-15, I-17, I-19, and I-25 dived more than 100 feet to the bottom and escaped the attack. Lt. Cmdr. Clarence W. McClusky, VF-6’s commanding officer, led six Wildcats of the 1st Division and bombed and strafed the airfield on Wotje, while gunfire from Northampton and Salt Lake City sank gunboat Toyotsu Maru at that atoll, and Dunlap shelled and sank auxiliary submarine chaser No. 10 Shonan Maru.

Lt. James S. Gray Jr., VF-6’s flight officer, led a half-dozen Wildcats against Taroa. F-14 (BuNo. 3914), Lt. (j.g.) Wilmer E. Rawie, tangled with a pair of Mitsubishi A5M4 Type 96 carrier fighters of the Chitose Kōkūtai (Air Group), flown by Lt. Kurakane Yoshio and PO3c Atake Tomita. Rawie tore into Kurakane’s plane, which burst into flames as the pilot bailed out and the fighter splashed into the water, scattering burning gasoline and debris. Rawie brought his Wildcat over in a sharp turn and confronted Atake head-on, but the planes collided. “This being my first head-on approach,” Rawie afterward journaled, “I muffed it & pressed home too far & hit the Jap’s wing with my underside.” The impact crumpled one of Atake’s wingtips and he landed immediately, while Rawie gamely attempted to strafe the airfield, but his guns jammed and he returned to Enterprise. Rawie received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his day’s work.

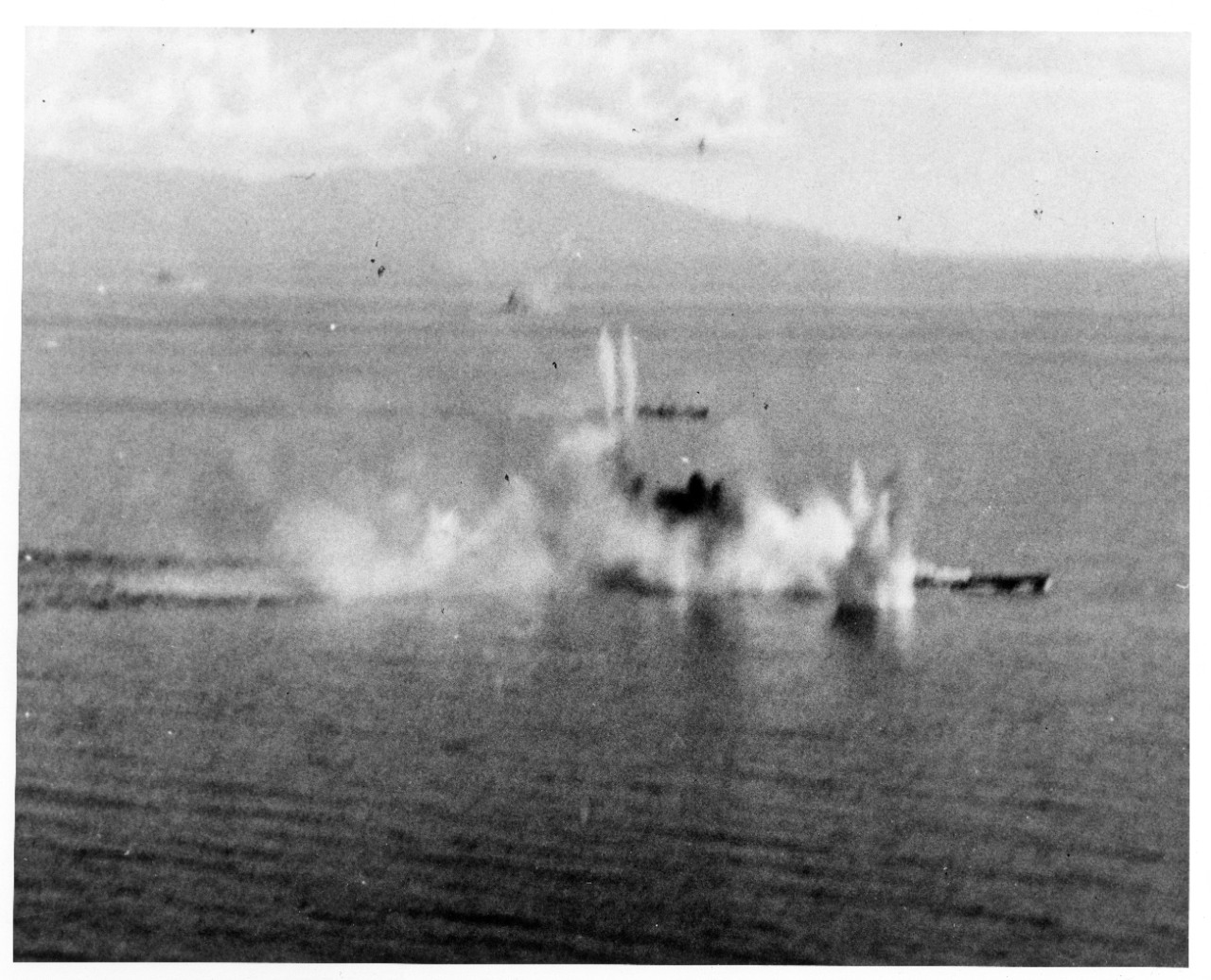

The enemy counterattacked during the afternoon watch and at 1338 five Japanese Mitsubishi G3M3 Type 96 land attack planes flying at 10,000 feet approached Enterprise on the starboard bow. The attackers broke into a shallow power dive to about 3,500 feet, and each plane released up to three bombs. Enterprise maneuvered at high speed and all of the bombs fell beyond the ship, the nearest about 50 feet off the port quarter at frame 130, raising splashes more than 100 feet high, and sending shock waves throughout the ship that crewmen compared to that caused by the ship firing her guns. Fragments struck the port quarter, though inflicted minimal damage. The Americans estimated that the bombs consisted of general purpose devices with instantaneous fuzes, weighing between 100 and 200 pounds, and intelligence data indicated that they appeared to possess a somewhat superior penetrating ability to similar U.S. bombs.

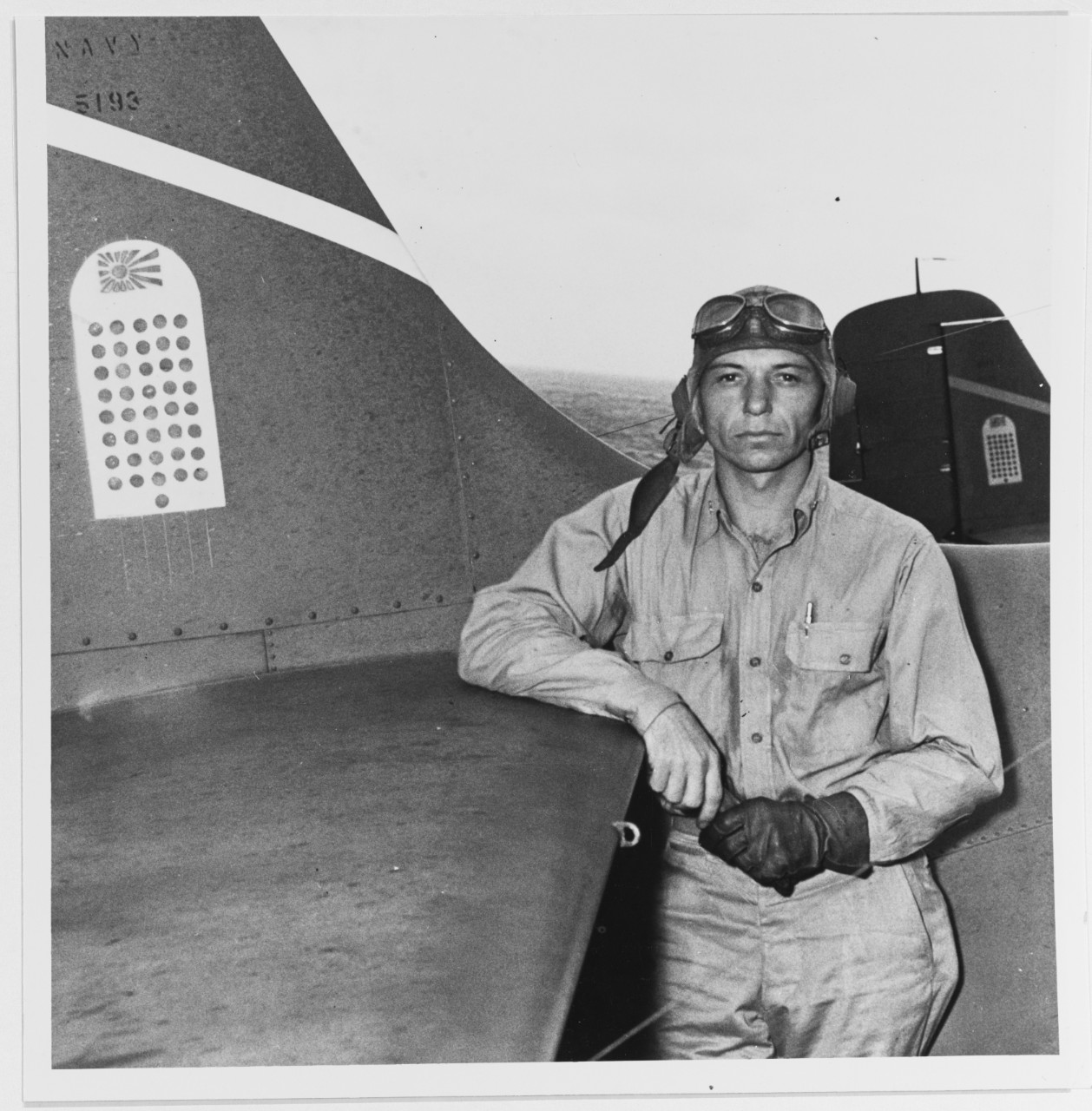

One of the Japanese planes returned, apparently to strafe the ship. AMM1c Bruno P. Gaido raced into a Dauntless (BuNo. 2155) parked on the aft portion of the flight deck and fired the guns at the attacker. The ship swerved hard left to dodge the plane but it crashed several feet from Gaido. Its right wing scraped the flight deck between frames 74 and 65, knocking off the ship’s port side light and cutting off the tail of the scout bomber, and plowed into the flight deck before skidding over the over the port side at frame 62, carrying away the forward stay of the antenna outrigger, while the ship steamed near 10°33'N, 171°53'E. Crewmen later pushed the damaged Dauntless over the side.

Fragments opened four 1/2-inch holes in the 1/4-inch medium steel plating of the port hangar bulkhead between frames 130 and 133 and six holes in the hangar roller curtain. They dented the 5/8-inch STS shell plating below the main deck and pierced and dented the splinter mats, gallery walkway, ladders, and gallery deck in way of the .50 cal. machine gun at frame 134. In addition, they pierced the externally-fitted 2 to 2-1/2-inch gasoline line in nine places between frames 119 and 135. Gasoline from the pierced gasoline line caught fire either from hot fragments or electrical short circuits, and the fire spread over the port gallery walkway and the boat pocket between frames 130 and 144. The flames consumed canvas covers, splinter mats, airplane fueling hose, rubber deck matting, life jackets, and paint on the deck and bulkheads. The flames roared into an inferno that threatened to spread across the ship, but sailors swiftly extinguished the blaze with chemical foam from pressure-operated foam generators. “By quick and effective use of the available firefighting apparatus,” War Damage Report No. 59 noted, “ENTERPRISE repair parties successfully passed their first real test.” The air group nonetheless recommended improving and increasing her antiaircraft batteries “at earliest date.”

A pair of Japanese Mitsubishi G3M3 Type 96s swooped in for a second attack against the ship at 1557, each dropping two bombs off the starboard bow. The nearest struck the water nearly 150 yards away and the splashes rose higher than those of the first bombs. Several fragments rained down on the forecastle but did not inflict damage. Another group of bombers approached but the Wildcats drove them off. A Mitsubishi A5M4 Type 96 damaged Chester, however, killing eight men and wounding 38. Planes flying from Yorktown caused less damage because of a paucity of targets at the objective, but Dauntlesses of VS-5 bombed and strafed gunboat Nagata Maru at Makin, while those of VB-5 bombed and strafed cargo ship Kanto Maru at Jaluit. The Americans lost six Dauntlesses over Roi: an SBD-2 (BuNo. 2120) manned by Ens. John Doherty and Will Hunt of VB-6; three more from VS-6 (BuNos 2114, 2155, and 2172) and two SBD-3s (BuNos 4645 and 4676), one of them flown by Lt. Cmdr. Halsted L. Hopping, VS-6’s commanding officer, and RM1c Thomas. In addition, the enemy shot down an SBD-3 (BuNo. 4522) of VB-6 over Taroa, and a TBD-1 (BuNo. 0274) from VT-5 disappeared. Fletcher detached three of his four destroyers to look for the Devastator, which was last reported in the water astern of the ships. A Japanese Kawanishi H6K4 Type 97 reconnaissance flying boat of the Yokohama Kōkūtai unsuccessfully attacked Sims (DD-409) as she searched for the missing crewmen. Two F4F-3 Wildcats of VF-42 splashed the intruder, but the searchers failed to locate the Devastator in the heavy seas. Enterprise recovered the last Wildcat of her CAP shortly after 1900 and retired to the northward at high speed. Nagumo responded to the raid by deploying some of the ships of Dai-ichi Kidō Butai, including carriers Akagi, Kaga, Shōkaku and Zuikaku, along with battleships Hiei and Kirishima, from Truk Lagoon in the Carolines, but came about on 4 February. Japanese submarines including I-9, I-15, I-17, I-19, I-23, I-25, I-26, I-71, and I-72 also prowled the area but failed to intercept the Americans and Halsey returned to Pearl Harbor on 5 February.

Halsey led the task force, reclassified as TF 16.1 on 14 February 1942, and the following day to TF 16, against the Japanese garrison at Wake Island, which the enemy renamed Otori-Shima (Bird Island). A U.S. airplane flying from Midway had photographed Wake following the Japanese conquest and provided Halsey a glimpse of the enemy’s preparations since their landings. The Navy meanwhile further evaluated ship design and effectiveness, and Adm. King authorized the removal of the athwartships hangar deck catapults from Enterprise, Hornet (CV-8), Wasp (CV-7), and Yorktown, on 17 February.

Brown led TF 11 and Lexington against Rabaul on New Britain as a diversionary raid, but on 20 February a Japanese Kawanishi H6K4 Type 97 flying boat of the Yokohama Kōkūtai (Air Group) spotted the ships en route. Brown cancelled the strike and two waves of 17 Japanese Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 land attack planes of the 4th Kōkūtai attacked the Americans off Bougainville in the Solomons. F4F-3 Wildcats from VF-3 and SBD-3 Dauntlesses from VS-2 broke-up the attackers, and Wildcat pilot Lt. Edward H. O’Hare shot down four of the attackers and damaged two more, an exploit for which O’Hare received the Medal of Honor. The intrepid pilot later served on board Enterprise. Halsey nonetheless continued toward his objective of Wake Island but as an F4F-3A (BuNo. 01997), Ens. Norman D. Hodson, took off to fly an inner air patrol during the morning watch on 21 February, the Wildcat suffered propeller pitch control problems, and, unable to gain enough air speed, went over the side. The plane sank quickly but Hodson escaped and Blue picked up the shaken pilot. Reports indicated enemy aircraft approaching the ships just after noon on 22 February, and Enterprise sounded general quarters but an attack did not materialize. The force was redesignated TF 16.8 on 23 February. On 24 February Halsey attacked, splitting his ships into two task groups: Enterprise, Blue, Craven, Dunlap, and Ralph Talbot (DD-390) swooped down on the island from the north; and Spruance led a bombardment unit consisting of Northampton, Salt Lake City, Balch, and Maury that shelled the atoll.

Treacherous weather, including frequent squalls and a heavy overcast, hampered the raid and delayed the launch of the strike. As Ens. Teaff launched in the second Dauntless, an SBD-3 (BuNo. 4524), at about 0544, he became disoriented by the horizon, veered off the flight deck slightly to port and plunged overboard ahead of the ship, just forward of No. 2 5-inch gun. The crash severely injured Teaff, who lost his right eye, but he survived, though his gunner, RM3c Jinks, died. Several other pilots experienced similar disorientation but launched successfully, and Navy investigators afterward surmised that as the plane’s engines’ turned up, the propellers caused a “halo effect”, brightly lighted by exhaust fumes. This halo, in turn, gave to some of the men the feeling that they were turning to starboard, and in consequence, they took off from the port side of the flight deck.

The ships enforced radio silence in order to surprise the enemy but the lost time proved critical and Halsey finally directed the attack to begin shortly after 0800. Thirty-six SBD 2 and 3 Dauntlesses from VB-6 and VS-6, respectively, and TBD-1 Devastators from VT-6 launched from Enterprise and bombed and strafed ships and installations. In addition, Northampton and Salt Lake City catapulted SOC 1 and 2 Seagulls of VCS-5 that bombed the enemy positions. Cmdr. Young, the photographic section, and a section of the torpedo squadron joined for a composite bombing run on the gasoline stowage at the southwest end of Wake. Another torpedo section made its first run on an antiaircraft battery east of the new channel on Wilkes Island, and a second on the Pan-American Airways gasoline tanks on the eastern end of the island. Two more drops struck buildings in the marine camp, the attackers often releasing their bombs in salvos and ripples. The scout bombers completed the dive-bombing phase of the attack at about 0815, and finished glide attacks with light bombs a few minutes later, retiring to the eastward. The torpedo squadron completed its attack at 0840 and proceeded to eastward for a rendezvous. The other planes rendezvoused separately with their squadrons and the entire group reconvened over the carrier about an hour later.

The raiders caused minimal damage and their combined bombing and shelling sank only two guardboats, No. 1 Miho Maru and No. 5 Fukyu Maru. The American marines, sailors, and construction workers captured by the Japanese during the seizure of the island, some of them too badly wounded to have been evacuated in the initial increment of POWs, along with the civilian workmen of Contractors Pacific Naval Air Bases, retained to continue work on the defenses, survived the raid. 6-S-18, Ens. Delbert W. Halsey and AOM2c A.T. Alford, reported a four-engine patrol plane approximately five miles east of Wake. The Wildcat patrol descended from 15,000 feet to 1,000 feet through broken clouds, overtook the enemy snooper and three Wildcats flown by Lt. Cmdr. Clarence W. McClusky, Lt. Roger W. Mehle, and Lt. (j.g.) Edward H. Bayers shot it down in view of the bombardment group, which brought cheers from some of the men on board the ships.

The Japanese antiaircraft batteries fired sporadically and largely ineffectively, although their shells occasionally reached a height of 19,000 feet. Some of the enemy erratically fired light- and heavy-caliber machine-gun from pits along the beaches. The Japanese shot down 6-S-8, an SBD-2 Dauntless (BuNo. 2174) manned by Ens. Percy W. Forman and AVMM2c John E. Winchester of VS-6. They captured and interrogated the two men, and then embarked them on board victualling stores ship Chichibu Maru for a voyage to a prison camp in Japan. Gar (SS-206) torpedoed and sank Chichibu Maru between six and ten miles southwest of Mikura Jima, south of Tōkyō Bay, near 33°53'N, 139°29.5'E, on 13 March and both men went down with the ship.

Enterprise recovered the attack group by 1014 and then came about to the northeast. At 1125 she launched a trio of Wildcats of VF-6 to intercept an enemy plane reported trailing Northampton, which steamed about 100 miles to the southwest. Because of changing winds and rain squalls the fighters failed to locate either Northampton or her elusive shadower. The changing weather, particularly a lack of upper air soundings, and the ship’s subsequent change of course, which was not transmitted to the aircraft, complicated their return to the carrier. The Wildcats burned their fuel to dangerously low levels before they succeeded in contacting Enterprise. As a result, 6-F-2, an F4F-3 (BuNo. 4017) flown by Ens. Joseph R. Daly, ran out of gas and made a down-wind landing in water close aboard the carrier. The plane sank almost immediately, but Ralph Talbot picked up Daly, who survived with only slight injuries. Two days after the raid Enterprise lost S-B-16, an SBD-2 (BuNo. 2140), Lt. (j.g.) Leonard J. Check and ARM2c S.J. Mason of VB-6. While the ship fought these battles Carrier Replacement Air Group (CRVG) 9 was established at NAS Norfolk, Cmdr. William D. Anderson in command, on 1 March. The action marked the first numbered air group in the Navy and the end of the practice of naming air groups for the carriers to which they were assigned. The Enterprise Air Group was subsequently redesignated CVG-6.

Halsey next moved the force, redesignated TF 16.5 on the first of the month and comprising Enterprise, Northampton, Salt Lake City, Balch, Blue, Craven, Dunlap, Maury, Ralph Talbot, and Sabine, against Marcus Island. Just before sunrise at 0447 on 4 March, the ship launched six F4F-3A Wildcats of VF-6 and 32 SBD 2 and 3 Dauntlesses of VB-6 and VS-6, respectively, from a point about 125 miles northeast of Marcus. The carrier’s radar directed the planes to their attack against the enemy garrison, and a Japanese radio blared a warning until an American bomb silenced the transmitter. Antiaircraft fire shot down an SBD-2 (BuNo. 2152), Lt. (j.g.) Hart D. Hilton and RM2c Jack Leaming of VS-6, which ditched east of Marcus. The enemy captured Hilton and Leaming and took them to Japan, though they survived captivity. A Japanese airplane flying from Iwo Jima in the Kazan Rettō (Volcano Islands) reached the area toward the end of the raid and radioed a further warning to the Japanese. I-15, Cmdr. Ishikawa Nobuo, sighted some of Halsey’s ships as they cancelled a planned rendezvous with TG 16.9 and returned on 7 March, but Ishikawa failed to maneuver to a favorable attack position. Following her homecoming Enterprise accomplished alterations at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard, including removing ten boats and most of the .50 cal. machine guns, and installing additional radar and 30 20 millimeter guns (10–26 March). On 22 March Lt. Cmdr. McClusky reported to relieve Young in command of the air group.

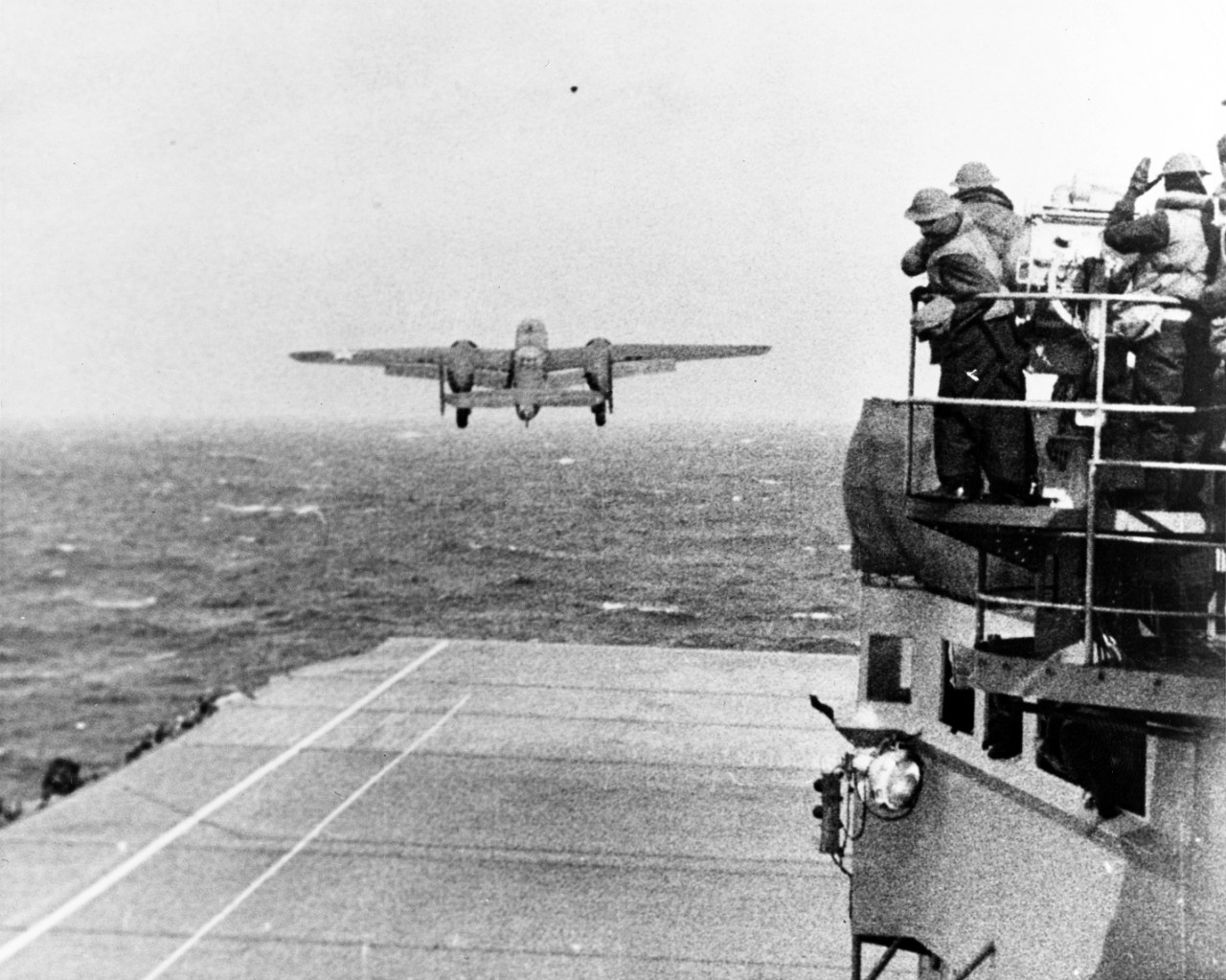

The Americans in the meantime made the daring decision to strike the Japanese home islands, weighing the possibility of launching Army bombers from a carrier. Hornet, Capt. Marc A. Mitscher in command, departed from Norfolk with two USAAF North American B-25Bs on her flight deck to practice the concept, on 2 February 1942. During the afternoon watch, Hornet launched the Mitchells, piloted by Lt. John E. Fitzgerald, USAAF, and Lt. James F. McCarthy, USAAF, to the surprise and amazement of the ships company, as security precautions prevented most of the men from knowing the meaning of the experiment, and returned to Norfolk Navy Yard for repairs and alterations. Lt. (j.g.) Henry L. Miller trained the crewmen of 24 B-25Bs of the Army’s 17th Bombardment Group, Lt. Col. James H. Doolittle, USAAF, in command, in carrier procedures at Eglin Field, Fla. The Mitchells’ crews volunteered for a mission that would be “extremely hazardous, would require a high degree of skill and would be of great value to our defense effort.” They practiced intensive cross-country flying, night flying, and navigation, as well as “low altitude approaches to bombing targets, rapid bombing and evasive action.” Doolittle noted that Miller’s “tact, skill and devotion to duty” proved crucial in training the aircrews in the often dangerous carrier operations. Maintainers installed additional fuel tanks in the Mitchells and removed “certain unnecessary equipment” to ensure that they could launch from Hornet and reach their targets.

Mitscher took Hornet out from Norfolk as part of TF 17 on 4 March, shaped a course for the West Coast, passed through the Panama Canal on 11 March, and on 20 March reached NAS Alameda, Calif. Following their training meanwhile, some of the Mitchells crossed the country in a series of flights, and with her own planes stowed on the hangar deck, Hornet loaded 16 of the Army bombers on the flight deck while at Alameda on 1 April. Altogether, Doolittle brought 70 officers and 64 enlisted men to fly and maintain the aircraft. Under sealed orders Hornet slipped through the fog and under the Golden Gate Bridge on 2 April, and in company with Vincennes (CA-44), Nashville (CL-43), Grayson (DD-435), Gwin (DD-433), Meredith (DD-434), Monssen (DD-436), and Cimarron (AO-22), proceeded into the Pacific as TF 18. That afternoon the boatswain’s pipe drew men’s attention as Mitscher informed the carrier’s crew of their mission. Cheers echoed through the ship, and when Hornet signaled the announcement to the other ships, morale soared on board those vessels.

Enterprise took part in the secret mission and prepared by training her newer pilots north of the Hawaiian Islands (27 March and 1–3 April). On 2 April, nine VB-6 Dauntlesses patrolled in a formation when two of the SBD-2s (BuNos 2136 and 2165), Ens. Stephen C. Hogan Jr., USNR, and AMM2c W.T. Thompson, and Ens. Harry W. Liffner, USNR, and AMM2c P.N. Altman, collided. The day was a favorable one for flying with good weather, but Liffner and Altman, flying the No. 3 plane in the 3rd Section, dropped back slightly from the section leader. Hogan and Thompson failed to follow their section leader closely, moved out and then forward, and slammed into the other Dauntless. The pilots survived but both of the gunners died, and some of their squadron mates surmised that their breast plate armor may have hindered them from bailing out. Halsey and TF 16, comprising Enterprise, Northampton, Salt Lake City, Benham, Ellet, Fanning, Gridley, Maury, and McCall, sortied from Pearl Harbor on 8 April. On 13 April Halsey and Mitscher rendezvoused north of the Hawaiian Islands, and the two forces fell under the former’s command as TF 16 and turned toward Japan. Foul weather harried the ships during most of their journey but helped shroud them from detection.

The Japanese nonetheless monitored U.S. Navy radio traffic and deduced that the Americans could (potentially) launch a carrier raid on their homeland after 14 April, and prepared accordingly. Lacking radar, they developed a rudimentary “early warning” capability by deploying parallel lines of guardboats, radio-equipped converted fishing trawlers, operating at prescribed intervals offshore. As the darkened U.S. ships sliced through heavy seas during the mid watch on 18 April, Enterprise detected intruders on her radar, and at 0315 signaled the other vessels ominously: “Two enemy surface craft spotted.” The force manned their battle stations and watchstanders anxiously monitored the situation. As the day dawned, cold and grey, lookouts spotted Japanese guardboat No. 23 Nitto Maru at a distance of 20,000 yards at 0738, in a position about 668 miles from Tōkyō. The Americans had intended to close the Japanese homeland to shorten the flying range but because of the discovery Halsey launched the raid earlier than planned, in order to avoid potential retaliatory aerial attacks from bombers flying from Japanese airfields.

As Hornet swung about and prepared to launch the bombers, which had been readied for take-off the previous day, a gale of more than 40 knots churned the sea with 30-foot crests; heavy swells, which caused the ship to pitch violently, shipped sea and spray over the bow, and drenched the deck crews. Doolittle flew the first heavily-laden bomber down the flight deck, and shook many of the man watching tensely when he dropped momentarily in altitude, and then rose, circled Hornet, and set a course for Japan. By 0920 all 16 of the bombers were on their way for the first American air strike against the heart of the Japanese Empire. The attackers bombed military and oil installations and factories at Kōbe, Nagoya, Tōkyō, Yokohama, and Yokosuka. A bomb struck Japanese carrier Ryūhō (being converted from submarine depot ship Taigei) at Yokosuka, but the strike inflicted negligible damage. All of the Mitchells were lost — 15 crashed in China and the Soviets interned one at Vladivostok, but they later smuggled that crew to freedom across the Allied-occupied Iranian border. The Japanese savagely retaliated with reprisals against the areas in Chekiang [Zejiang] province, China, where people succored the aviators and butchered thousands of people, and in addition, captured eight of the fliers, afterward murdering three of the men. Doolittle survived and subsequently received the Medal of Honor.

Enterprise meanwhile launched F4F-3As of VF-6 for CAP and SBD-3s of VB-3 and SBD-2s of VB-6, and the Wildcats and Dauntlesses coordinated with surface attacks and damaged guardboats No. 23 Nitto Maru and Nagato Maru, which Nashville sank by gunfire. The carrier planes also damaged armed merchant cruiser Awata Maru and guardboats Chokyu Maru, Eikichi Maru, Kaijin Maru, Kowa Maru, No. 1 Iwate Maru, No. 2 Asami Maru, No. 3 Chinyo Maru, No. 21 Nanshin Maru, and No. 26 Nanshin Maru. The Japanese downed an SBD-3 (BuNo. 4603), Ens. Liston R. Comer, USNR, of VB-6. Hornet brought her own airplanes on deck and the ships came about and made full speed for Pearl Harbor. Intercepted broadcasts, both in Japanese and English, confirmed at 1445 the success of the raids. The following day light cruiser Kiso scuttled No. 21 Nanshin Maru by gunfire, and No. 1 Iwate Maru sank as the result of the damage inflicted by Enterprise planes. I-74 rescued No. 1 Iwate Maru’s crew and ultimately transferred them to Kiso on 22 April.

Nagumo and a force built upon carriers Akagi, Hiryū, Sōryū, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku was just returning from a thrust into the Indian Ocean and had reached a position east of Formosa [Taiwan] while en route to Japanese waters. He turned and pursued the raiders, but Halsey reversed course and opened the range. Rumors circulated through Enterprise about enemy action, including an alleged naval intelligence message that claimed that the Japanese carriers closed from 500 miles to the southwest, blocking the task force’s return to the Hawaiian Islands. The ships company ate battle rations but only relaxed when Enterprise secured from general quarters. Japanese submarines including I-8, I-21, I-22, I-24, I-27, I-28, and I-29 also unsuccessfully attempted to intercept the task force. Despite the infinitesimal material damage inflicted, the psychological impact of an aerial threat to Japan and to the Emperor ended debate within the Japanese high command concerning a decisive thrust against the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The task force’s return voyage did not pass without incident and on 21 April an F4F-3A (BuNo. 3894), AMM1c Howard S. Packard of VF-6, landed hard on the Enterprise flight deck, crumpling the left landing gear. Squadron mate Lt. (j.g.) Rawie later observed that Packard “sorta splattered one plane all over the F-3 area in general.” On that day reporters also queried President Roosevelt for the location from which the bombers launched on the Halsey-Doolittle Raid and he replied: “And I said, “Yes. I think the time has now come to tell you. They came from our new secret base at Shangri-La! [referring to the mythical haven in James Hilton’s novel Lost Horizon]” The ships returned to Pearl Harbor on 25 April, one week to the hour after Hornet launched the bombers.

The Japanese in the interim launched Operation MO — to seize Port Moresby, New Guinea, and points in the Solomon Islands, along with Nauru and Ocean Island [Banaba], preparatory to neutralizing Australia as an Allied bastion. Just five days after Enterprise moored at Pearl Harbor, she therefore stood down the channel and in company with Hornet sped toward the South Pacific to reinforce Lexington and Yorktown. The carriers and Pensacola carried VMF-212, which was to operate from Vila on Efate in the New Hebrides [Vanuatu] — Enterprise embarked ten of the squadron’s F4F-3s and Hornet carried 11. While Enterprise steamed toward the battle she lost two SBD-2 Dauntlesses (BuNos 2152 and 4595), Ens. Clifford R. Walters, USNR, and AMM2c P.S. Johnson Jr., and Ens. Thomas C. Durkin, USNR, and AM2c E.C. Bailey, during a scouting mission on the afternoon of 13 May. The planes and their crews vanished, though some of their VS-6 squadron mates vainly hoped that they set down on an island in the vicinity.

The ships’ distance from the action proved too great to conquer in time, and during the Battle of the Coral Sea, the first naval engagement fought without the opposing ships making contact, the Allies sustained heavy casualties but achieved a strategic victory by halting the push southward and blunting the seaborne thrust toward Port Moresby. The Japanese deferred and then abandoned their occupation of Port Moresby by sea and shifted their advance overland across the Owen Stanley Mountains. Enterprise and Hornet searched unsuccessfully for the retiring Japanese carriers, and for the Nauru and Ocean Island invasion forces. On 11 May, they launched the 21 marine Wildcats as VMF-212 temporarily deployed to Tontouta, about 30 miles northwest of Nouméa, New Caledonia, while staging to Efate. On 16 May Nimitz directed the ships to come about for Pearl Harbor, and sent a more urgent order the following day: “Expedite return”. Enterprise and Hornet made speed and returned to Pearl Harbor on 26 May, and began intensive preparations to meet the next Japanese thrust.

The threat posed by the U.S. carriers convinced the Japanese to occupy Midway Island to lure the Pacific Fleet into a decisive battle. Japanese Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku, Commander in Chief Combined Fleet, developed Operation MI — a comprehensive plan that emphasized attaining surprise. On 27 May Nagumo took Dai-ichi Kidō Butai, including Akagi, Kaga, Hiryū, and Sōryū, out from Japanese waters.