The U.S. Navy and the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95

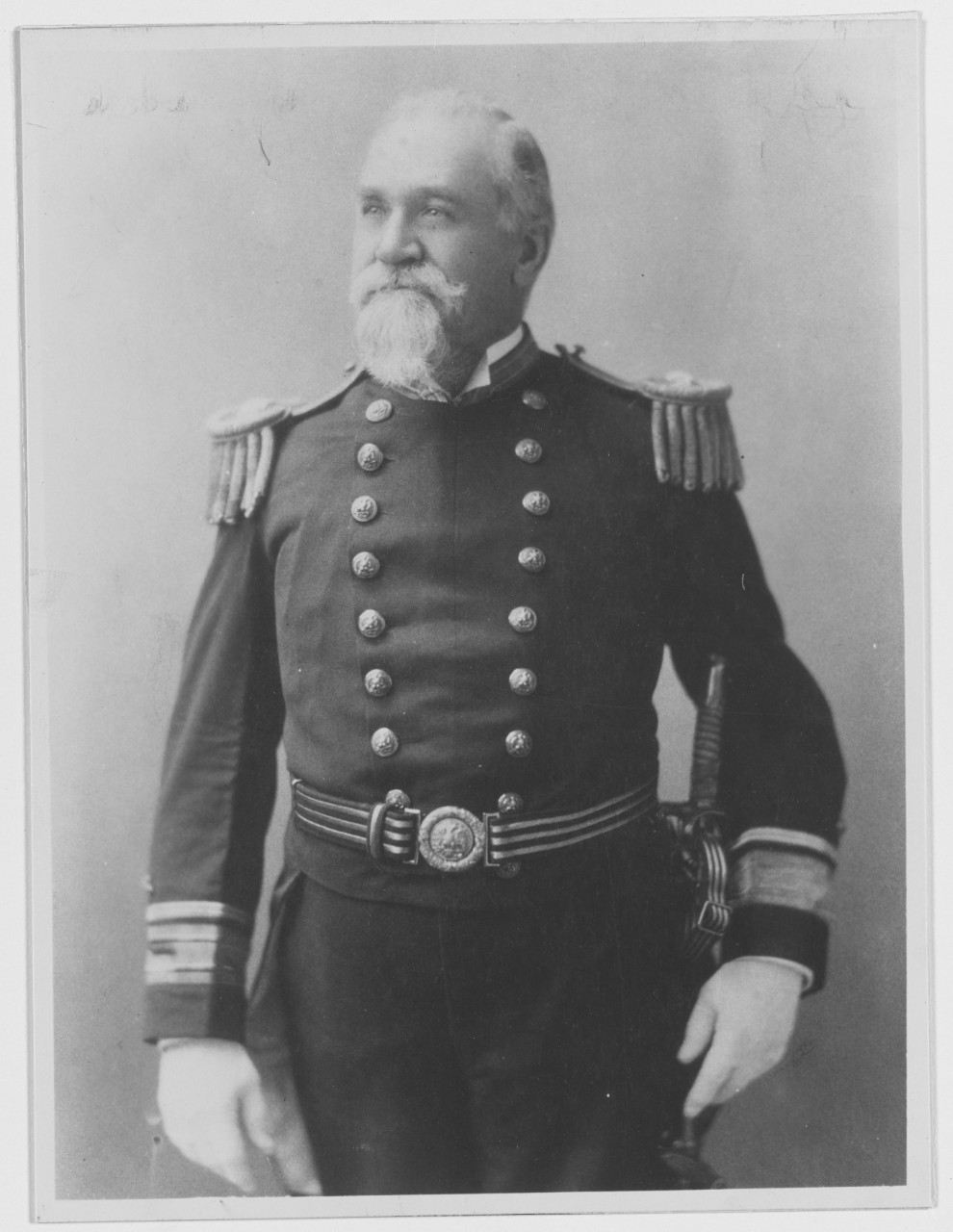

Rear Admiral Joseph S. Skerrett did not want to go to Korea.

It was May 1894, just months before Skerrett’s retirement, when he received an urgent telegram from the U.S. minister at Seoul, John M. B. Sill. A peasant revolt was underway in Korea, and members of the American legation there, along with several dozen missionaries, were getting nervous. To make matters worse, it appeared as if the Japanese Empire meant to use the unrest as an opportunity to weaken China’s influence in the region.[1] That meant war.

Skerrett, for his part, was unsympathetic to missionaries and diplomats. Moreover, his Asiatic Squadron, small as it was, had spread itself thin. USS Baltimore was his only protected cruiser in the area, and he needed it for patrols. The answer to Sill, therefore, was no.[2]

It took the intervention of Korea’s king himself to get Baltimore to Seoul. An influential American missionary had persuaded the king to ask President Cleveland for a man-of-war, and President Cleveland obliged and gave the order that deployed Baltimore to Chemulpo Bay (about eight hours’ journey downriver from Seoul).[3] On board were 36 officers, 350 Sailors, and 21 Marines, whose job it might be to fight their way ashore should war break out between Asia’s two principal powers over control of the Korean peninsula.[4] As it happened, war did break out some eight weeks later. The U.S. Navy, through Baltimore, became the lifeline of Americans resident at the site of a war that would upset the balance of power in Asia and the course of world and U.S. history.[5]

Baltimore weighed anchor and departed Nagasaki Harbor on the afternoon of 3 June. Two days later, she arrived at her destination, where Chinese and Japanese preparations for war were already underway.[6] Baltimore’s watches sighted three Chinese cruisers, two Japanese cruisers, and the French unprotected cruiser Forfait, there to observe events and protect French interests in the region.[7] As was customary, Baltimore received and returned visits from each of these vessels and then welcomed her first of many diplomats, the Russian chargé d’affaires, whose government sought advantage in the insipient shakeup on the Korean peninsula.[8] Meanwhile, another Japanese ship, the gunboat Akagi, steamed into harbor.[9]

In the first week there, Baltimore received further visits of courtesy from Chinese and Japanese commanding officers as well as from the Korean governor of Chemulpo Bay and the vicinity (around present-day Inch’ŏn, South Korea), whose king’s sovereignty over the area was at this point only hypothetical. Still, the king hoped that the United States might intercede on his behalf and spare Korea the effects of a war on its own territory between its most powerful neighbors.[10] On 12 June, finally, the commander-in-chief of the Atlantic Squadron, Rear Admiral C. C. Carpenter, left Baltimore for Seoul to see conditions for himself and hear from members of the U.S. legation at their compound in the city center.[11]

No sooner had he left than a Japanese transport ship arrived, full of horses and troops, the latter disembarking right away. A British man-of-war arrived, too, and witnessed the offloading procedures. Then, six more Japanese troop ships came into the harbor to fill Chemulpo’s shores with men and materiel on the 15th. A day later, two Japanese men-of-war arrived on the scene, and more transports made deliveries of troops and supplies on 20 and 21 June, respectively.

On 22 June, the Chinese flagship Chen Yuen, as well as the torpedo gunboat Kuang Ping and the cruiser Chao Yung, steamed into port, their crews bearing witness to the menacing buildup on shore.

In fact, the Japanese mobilization was in part a response to a Chinese mobilization already underway via rail and road from Manchuria. When confronted with a peasant revolt, the king had asked the Chinese to send troops that might shore up the government. When China did so, however, it failed to notify Japan and therefore broke an agreement between the two countries to do so.[12] To make matters worse, the peasant rebels torched the Japanese legation in Seoul to show their extreme displeasure with that country’s economic domination of Korea.[13]

Korea, therefore, found itself by summer 1894 in the middle of a power struggle between Asia’s up-and-coming power, Japan, and the continent’s traditional hegemon, China. European imperialism only exacerbated the situation, with the king of Korea hoping that the United States might somehow help him out of this perilous situation.[14]

In late June and into July, matters escalated. In addition to the arrival of SMS Iltis, a German gunboat, eight more Japanese transport steamers and two more cruisers anchored at Chemulpo Bay.[15] Everyone expected the worst as still more ships from all the principal naval powers of the day laid claim to Seoul’s anchorage and as Japanese troop transports continued to unload as the crew of Baltimore watched.[16]

Crisis in Seoul

The U.S. legation to Korea occupied a small compound in Seoul, where chaos overtook order as Japanese troops assembled outside the city gates. The U.S. minister, John M. B. Sill, cabled again for Baltimore to send a shore party to protect him, his staff, and the missionaries and Korean civilians who had made the legation compound their refuge in anticipation of a Japanese siege.

Captain B. F. Day, Baltimore’s commanding officer, declined to assist and reminded the U.S. minister that he and the other Americans should be safe so long as they stayed out of the way.[17]

Day continued to refuse assistance even as Japanese forces breached Seoul’s walls and occupied the royal palace on 22 July. In the end, Sill had to appeal to Walter Q. Gresham, U.S. Secretary of State, who received Sill’s frantic cable on 23 July and replied with an urgent cable of his own to Baltimore.[18] A detail of Marines and Sailors were to proceed to Seoul at once.[19]

With orders from Washington, Captain Day authorized the landing right away. Captain G. F. Elliott, USMC, would be in charge and would receive a detail of two ensigns, a cadet midshipman, an assistant surgeon, the paymaster’s clerk, and 20 or so Sailors, in addition to his 21 Marines.[20]

With a siege on and other Western vessels trying to get landing parties ashore, Baltimore’s officers had trouble finding a pilot to take the Marines and Sailors upriver to Seoul. Sensing the urgency, Captain Elliott decided that he and his Marines would march to Seoul overnight and expect the Sailors and supplies to arrive by boat as soon as they could.

And so, beginning at 7:30 p.m. on 24 July, Captain Ellis marched his 21 Marines over difficult and dangerous terrain. The road to Seoul, “little more than a footpath [that] varied in degrees of wretchedness,” led the men over hills of clay, a mountain pass, and miles of loose sand. They had to ford two streams, and all of this in “extreme” darkness, heat, and humidity. Moreover, Elliott and his men were forced to pursue a tortuous route in order to avoid Japanese troop movements. The Marines, having gone a year without drilling on shore, “were severely taxed,” yet everyone made it to Seoul, a journey of 31 miles, and in 11 hours.[21]

On their approach to the city, the men passed thousands of Korean civilians in flight from the siege. “On seeing us,” Elliott reported, “they always hastily deserted the road.”[22] The refugees had good reason to fear the spectacle, for the column of U.S. Marines was headed by a Japanese guide in military dress and on horseback.[23]

His uniform and his equestrian pose caused great consternation among Korean civilians and then among the refugees in the U.S. legation compound, who were not expecting the gates to open for what appeared to be an invader on horseback. As head of the legation, Sill was furious: “This act added intensity to the growing anti-American feeling” in the city, he wrote Captain Day.[24]

Sailors Go Ashore

Meanwhile, just before sunrise, the Navy’s party left Baltimore in four boats. Ensign G. N. Hayward was in charge of the four junior officers and 24 enlisted Sailors, who carried 150 rounds of ammunition per man as well as some necessary equipment and provisions to last 30 days.[25]

Their four boats could only get so far up the Han River before having to stop because of Japanese troop movements. Ensign Hayward and his men therefore landed about three miles away and had to walk the rest of the way to Seoul. The Sailors carried hundreds of pounds of supplies and equipment along paths choked by refugees streaming in the opposite direction. From Baltimore to the legation compound, the trip ended up lasting 20 hours, almost twice the time it had taken the Marines. The heat must have been terrible, with two of the men “in the hands of the surgeon” by the time of their arrival at the compound.[26]

Less than two hours after the Navy detachment’s departure, Baltimore’s remaining crew heard what the deck log calls “heavy firing for about an hour.” Although neither they nor the world knew it, this was the first naval battle of the Sino-Japanese War, some 25 miles away. Lasting little more than a half hour, the battle resulted in the loss of two Chinese gunboats (one sunk, one captured) and the sinking of a Chinese transport ship, Kowshing, a British vessel leased to the Chinese government as a troop transport. Helmed by an Englishman and crewed by Europeans, Kowshing’s sinking—as well as the drowning or shooting of most of the crew and about 800 Chinese soldiers—became an international incident and media sensation.[27] The war was off to a gruesome start.[28]

Back in Seoul, Captain Elliott, his Marines, and his Navy detail got to work securing the legation compound and establishing a military encampment. Sentinels manned both of the gates and the perimeter roads. Nearby legations took similar actions. “All thoroughly understood the situation,” Captain Elliott reported. In the event of a Japanese defeat, the Japanese legation compound “would probably be sacked.” Moreover, “an event of this kind,” Elliott explained, “would endanger the lives of all foreigners, for there is a strong party of Koreans whose cry is for Koreans.”[29]

A Korean independence movement with a mass base and revolutionary message; a land and sea war between the region’s foremost military powers; a cohort of European agents intent on finding advantage in the chaos—this was a dynamic and dangerous situation, to be sure. The Marines and Sailors were going to have to stay put and dig in. As the days went by, they managed to make their encampment more livable with the addition of floorboards, mosquito nets, and a bathing facility—anything to make the camp “comfortable,” according to Captain Elliott, or, at least, “as comfortable as the extreme heat would allow.”[30]

Over the course of the next weeks, supplies came regularly from Baltimore’s steam cutter, or motorized transport boat, the route having become easier to travel now that the war was happening elsewhere in the kingdom. Nevertheless, Chemulpo Bay remained very active. Baltimore’s crew observed the landing of Japanese troops well into September, in preparation, it turned out, for the Battle of P’yŏngyang, which resulted in another Chinese defeat on 15 September. The naval battle of Yalu, on the following day, ceded command of the sea to Japan. Yet the war continued.

Around the same time, USS Concord and a fresh detachment of Marines arrived to relieve Elliott and his men. The Marines returned to Baltimore on the evening of 27 September, but they and the ship stayed at Chemulpo Bay to assist with supplying the encampment at the legation compound. Finally, on 27 November, Baltimore returned to Nagasaki for maintenance and supplies.[31]

When she arrived there two days later, however, a telegram was waiting. Baltimore and Elliott’s Marines were to proceed at once to Tianjin, China, the seaport closest to Beijing. That city was now under threat from Japanese troops advancing through Manchuria, and the U.S. legation there had requested protection in the event of a siege.

Before Japanese forces got the chance to besiege Beijing, however, the Chinese government sued for peace in March 1895. Their defeat was total and humiliating. It also portended a sea change in world history: the rise of Japan, the first non-western imperial power in its own right.[32] Japan’s victory in 1895, and the peace agreement that guaranteed it, turned Taiwan into a Japanese colony and set the stage for a conflict with Russia, which now pressed its interests in Korea to check Japanese expansion.[33] The resulting war, between Japan and Russia in 1904–1905, ended in Russia’s abject defeat. Less than six years later, the Japanese Empire colonized Korea outright and became the principal rival of the United States for control of the Pacific Ocean.[34] The preconditions for World War II were now set, the culmination of a process that began in Korea in 1894, under the watchful gaze of Baltimore’s captain and crew.

—Adam Bisno, Ph.D., NHHC Communication and Outreach Division, July 2019

[1] Elizabeth Pollard, Clifford Rosenberg, Robert Tignor, et al., Worlds Together, Worlds Apart: From the Beginnings of Humankind to the Present—Concise Edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015), 632.

[2] Jeffrey Dorwart, The Pigtail War: American Involvement in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895 (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1975), 18–19.

[3] Unlike Admiral Skerrett, President Cleveland was highly sympathetic to missionaries. See ibid., 19.

[4] Ibid., 25.

[5] On this shift from the perspective of Britain, the world’s principal imperial power, see P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, British Imperialism, 1688–2000, second edition (Harlow, UK: Longman, 2001), 369. On the causal relationship between China’s defeat in 1895 and the establishment of western “spheres of influence” in that country, see Pollard et al., Worlds Together, 653. On U.S. involvement in Korea since 1866, see Jinwung Kim, A History of Korea: From “Land of the Morning Calm” to States in Conflict (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2012), 281–84 and 287–88.

[6] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894, entries of 3 June and 5 June, in Logs of US Naval Ships, 1801–1915, vol. 9, Record Group 24: Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, National Archives, Washington, DC. Hereafter: USS Baltimore Deck Log.

[7] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op. cit.), entry of 5 June.

[8] On Russian interests in the region, see Kim, History of Korea, 288, 298–99, and 312; Brett L. Walker, A Concise History of Japan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 208; Mark R. Peattie, “Japanese Colonial Empire, 1895–1945,” in The Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 6: The Twentieth Century, edited by Peter Duus (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 226.

[9] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op. cit.), entry of 5 June.

[10] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op.cit.), entry of 6 June; on the king’s hopes for U.S. benevolence and assistance, see Kim, History of Korea, 297.

[11] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op. cit.), entry of 12 June.

[12] Walker, History of Japan, 208.

[13] Ibid., 207–208; Kim, History of Korea, 303; Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 115; Pollard et al., Worlds Together, 632. Korea’s sovereignty was only ever theoretical in the eyes of its powerful neighbors. The Chŏson dynasty in Korea presided over what amounted to a tributary state: China exacted payments from Korea and largely determined the course of its foreign policy. But as Japanese economic, diplomatic, and political incursions increased in the last third of the 19th century, the Chŏson dynasty found itself forced to press the peasantry for ever more contributions to Japan’s insatiable market for rice and other foodstuffs.[xiii] This economic penetration of Korea had a political corollary: Japanese policy by the 1890s was to wrest Korea from China’s orbit and then colonize the Korean peninsula “just as western nations do,” in the words of Fukuzawa Yukichi, one of the principal ideologues of the Meiji restoration and overseas expansion. (Fukuzawa Yukichi quoted in Walker, History of Japan, 207.)

[14] Kim, History of Korea, 297.

[15] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op. cit.), entries of 26 and 27 June.

[16] From 6 to 17 July, Baltimore was absent from Chemulpo Bay. She had gone back to Nagasaki for supplies. USS Monocacy, the sidewheel gunboat launched during the Civil War, delivered still more supplies upon Baltimore’s return to Korea. USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op. cit.), entries of 6–17 July.

[17] Dorwart, Pigtail War, 25.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Captain G. F. Elliott, USMC, “Report,” in Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for the Year 1895 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895), 523. Hereafter: Elliott, “Report.”

[20] Ibid., 523. The precise number of Sailors is unclear from the sources.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Dorwart, Pigtail War, 26.

[24] Ibid.

[25] USS Baltimore Deck Log, 1894 (op. cit.), entry of 25 July.

[26] Elliott, “Report,” 524.

[27] See Douglas Howland, “The Sinking of SS Kowshing: International Law, Diplomacy, and the Sino-Japanese War,” Modern Asian Studies 42 (2008): 673–703.

[28] In fact, the formal declarations of war would not come until August.

[29] Elliott, “Report,” 524.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Annual Report of the Secretary of the Navy for the Year 1895 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895), xxiii.

[32] This process of course entailed Japan’s “extricating itself from the unequal treaty system imposed three decades earlier by the Western powers,” according to Walker, History of Japan, 208, a process that began with Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s “opening” of Japan in the 1850s.

[33] Peattie, “Japanese Colonial Empire,” 225–26. On the Treaty of Shimonoseki and the “triple intervention”—of France, Germany, and Russia—and the successful effort to minimize Japanese advantage after the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95, see Walker, History of Japan, 165; Kim, History of Korea, 312.

[34] For a discussion of this broader conceptualization of imperialism—“informal empire”—see John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson, “The Imperialism of Free Trade,” Economic History Review 6 (1953): 1–15. For how this concept relates to U.S. efforts in the Pacific and elsewhere, see A.G. Hopkins, American Empire: A Global History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 23.

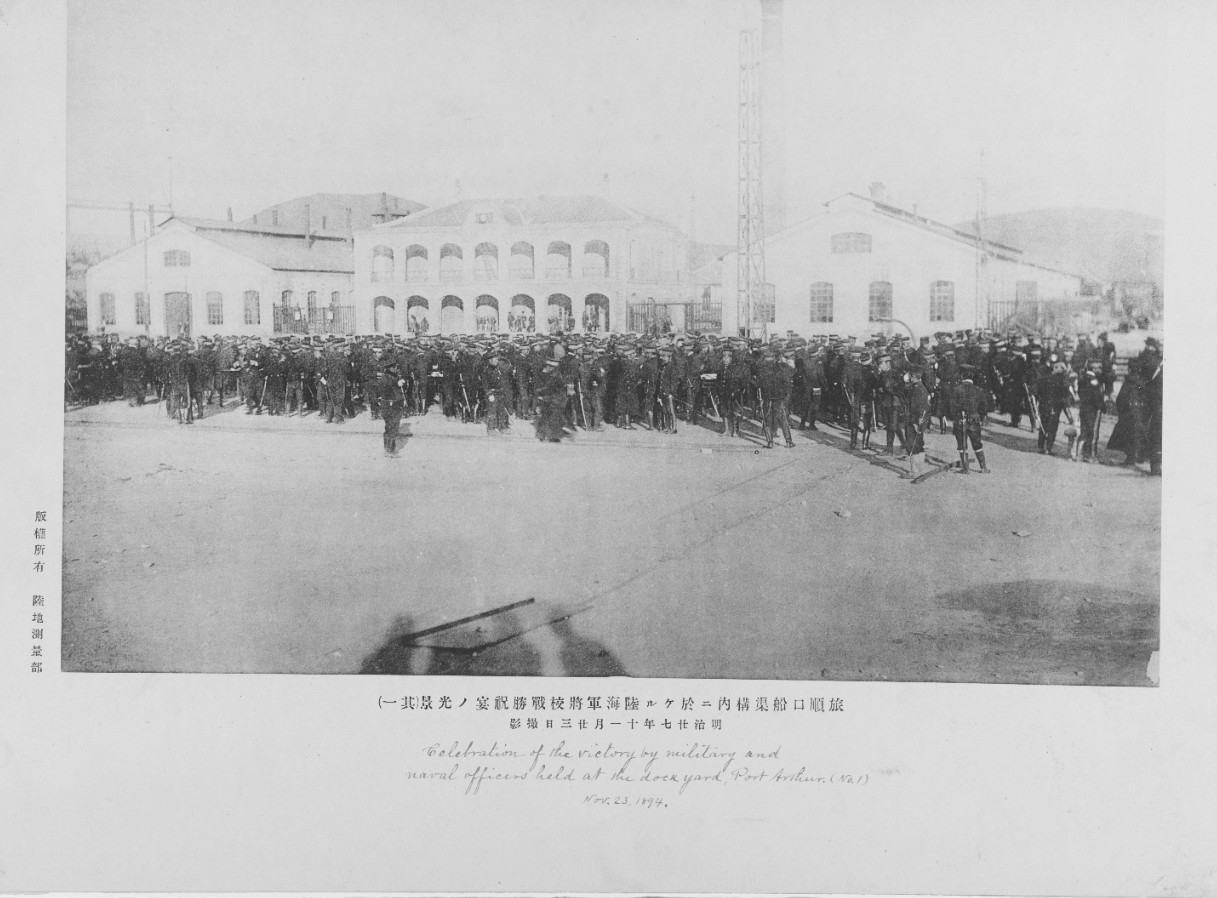

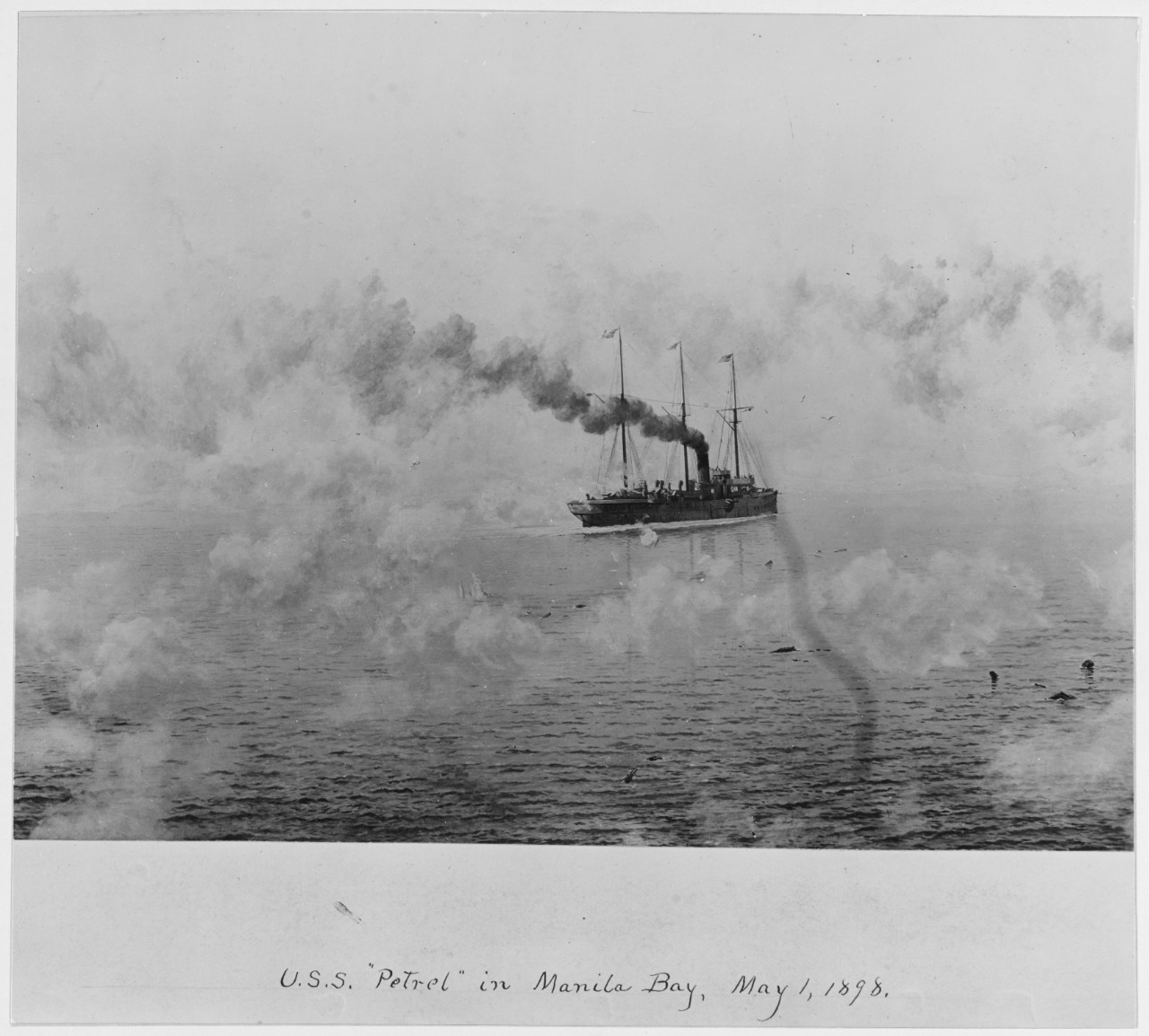

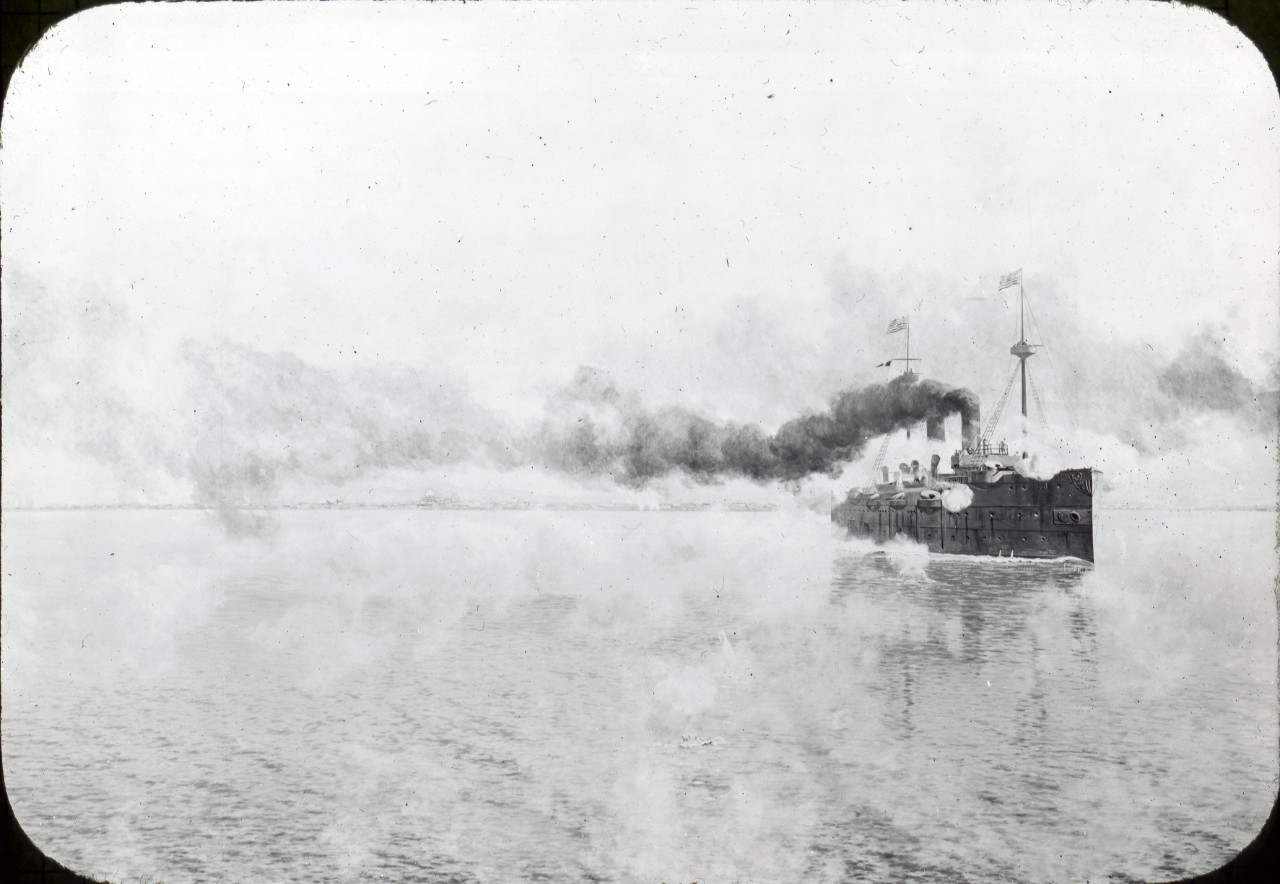

Selected Imagery:

In addition to the selected images, below, explore the Navy Art's Sino-Japanese War Woodblock Print collection.