St. Louis III (Cruiser No. 20)

1906–1930

The third U.S. Navy ship named for the city on the Mississippi River, the largest city in the state of Missouri.

III

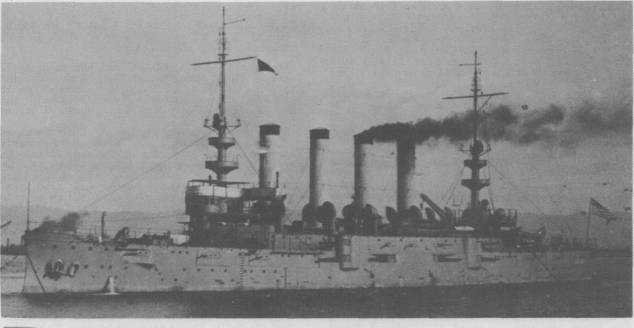

(Cruiser No. 20: displacement 9,700; length 426'6"; beam 66'; draft 24'10"; speed 22 knots; complement 673; armament 14 6-inch, 18 3-inch, 12 3-pounders, 8 1-pounders, 4 .30 caliber machine guns; class St. Louis)

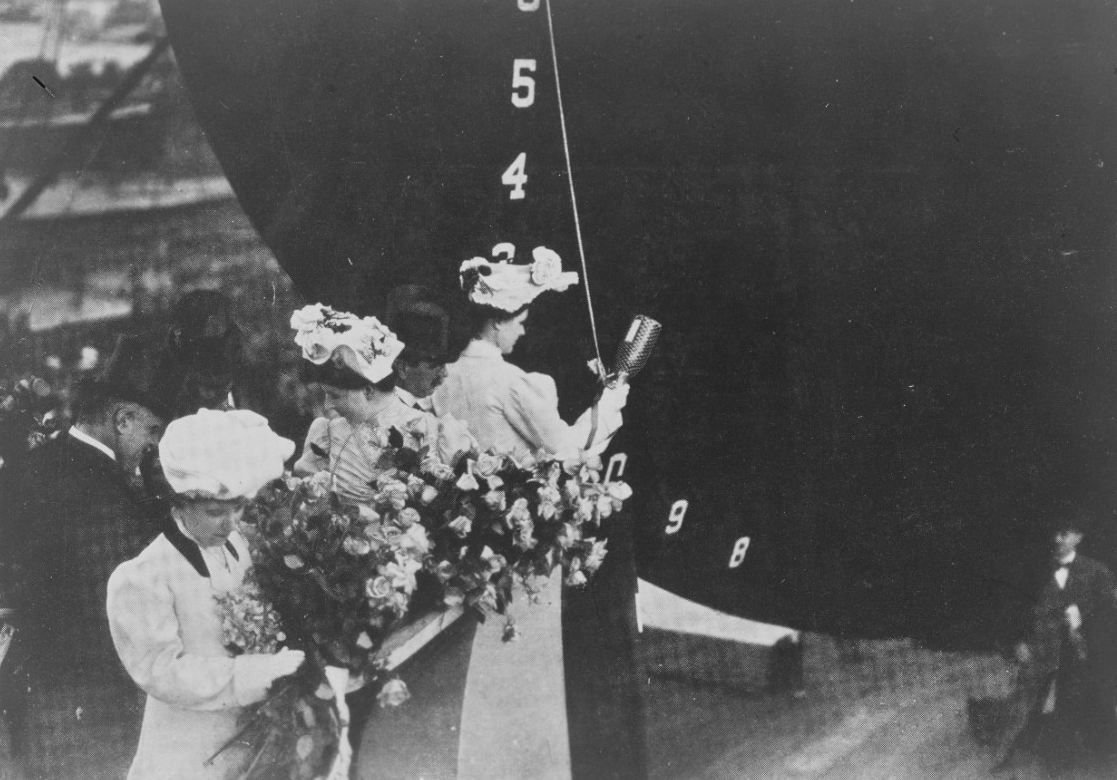

The third St. Louis (Cruiser No. 20) was laid down on 31 July 1902 at Philadelphia, Pa., by Neafie & Levy, Co.; launched on 6 May 1905; sponsored by Miss Gladys B. Smith; and commissioned on 18 August 1906, Capt. Nathaniel R. Usher in command.

St. Louis completed her trials along the Virginia coast (1 February–24 March 1907), stopping recurrently at Fort Monroe, Sewells Point, the Southern Drill Grounds, and Lynnhaven Roads, Va. The cruiser rejoined her consorts at Hampton Roads, Va., and soon (28 March–4 April) turned her bow southward for fleet maneuvers in the Caribbean. The ship operated off Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, shot at targets on the range at Cape Cruz in that country, and returned to Hampton Roads to prepare for her assignment to the Pacific Station in what the Bureau of Navigation succinctly reported as “foreign service.” St. Louis spent five days (13–18 April) carrying out the filthy and laborious but necessary task of coaling at Newport News, Va., steamed to New England waters to embark a draft of men at Newport, R.I. (19–20 April), and returned to Newport News and disembarked the men. The ship broke her preparations for deployment and participated (23–29 April) in a portion of the Jamestown Exposition, commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony, held at Sewells Point. St. Louis then (1–15 May) accomplished repairs and alterations in dry dock at New York Navy Yard.

The warship wrapped-up her yard work and set out from nearby Tompkinsville, on Staten Island, N.Y., for a voyage around South America (15 May–31 August 1907). St. Louis battled heavy seas on more than one occasion and called at: Port Castries, St. Lucia; Bahia and Rio de Janeiro (13–18 June and 21 June–5 July, respectively), Brazil; Montevideo, Uruguay (9–16 July); Punta Arenas and Valparaiso, Chile (21–23 July and 29 July–2 August, respectively); Callao, Peru (6–15 August); and Acapulco, Mexico (22–25 August), before arriving at San Diego, Calif. The ship completed an overhaul at Mare Island Navy Yard, Calif. (2–27 September), with a brief stop on the 24th and 25th for an admiral’s inspection off Angel Island. The cruiser carried out target practice in Magdalena Bay, Mexico (11 October–5 December 1907 and 9 February–9 March 1908, respectively), where she also held a full-power trial for eight hours on 9 March. St. Louis conducted what the Bureau of Navigation reported as “special service” from Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash. (27 March–12 June), and then (19–29 June) made for Honolulu, T.H., where she embarked Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield, and carried the son of the late President to San Francisco, Calif.

The warship trained along the west coast into the summer, and after celebrating Independence Day in the Bay Area carried Rear Adm. Charles M. Thomas, Commander, Second Squadron, to Bremerton (6–10 July), where the cruiser was placed in reserve on 13 July 1908. St. Louis visited Seattle and Port Madison, Wash. (6–7 June 1909), and (12–13 and 20 June, respectively) California City and Santa Barbara, Calif., but otherwise worked-up in those waters until she charted a course across the Pacific (26 June–22 August). The ship celebrated Independence Day at Honolulu and visited Suva in the Fiji Islands (15–23 July), Tutuila, Samoa (24–28 July), and Honolulu again (7–15 August) and Hilo (16–17 August) in the Hawaiian Islands, before returning to San Francisco. St. Louis trained along the California coast into the autumn and carried out special service off Santa Monica (7–11 September), San Pedro (11–18 September), and San Francisco (19 September–1 November), coaled at California City, and on the 4th turned northward for Bremerton, where she was placed in reserve on 14 November.

Decommissioned at 11:00 a.m. on 3 May 1910 at Puget Sound Navy Yard, St. Louis was recommissioned, in reserve, on 9 October 1911. The ship next (13–16 December 1911) stood out of the navy yard, bound for San Francisco and brief service as the receiving ship there. After undergoing repairs drydocked at Mare Island (22–25 January 1912), she joined the Pacific Reserve Fleet again on 12 March. Into the following year (14 July 1912–26 April 1913), St. Louis operated in support of the Oregon Naval Militia, visited Seattle (14–23 July) and Bellingham (23–26 July), Wash., and then returned to Puget Sound Navy Yard. The cruiser took part in a commemoration honoring the nation’s hallowed fallen over Memorial Day (29–31 May) held at Tacoma, Wash., and then tested her engines and boilers while moored at Bremerton.

St. Louis embarked Oregon naval militiamen and steamed up the Columbia and Willamette Rivers to take part in the Portland Rose Festival, Ore. (8–15 June), but as the ship returned to the sea at Astoria she battled the tide, which compelled her to anchor overnight. St. Louis rendezvoused with F-4 (Submarine No. 23), Lt. (j.g.) Kirkwood H. Donavin in command, First Submarine Group, Pacific Torpedo Flotilla, at Neah Bay, Wash. (16–18 June). Both vessels anchored while the cruiser took on stores from the submarine, and St. Louis then (19–20 June) convoyed F-4 to San Francisco. The warship came about and disembarked her militiamen at Astoria (24–25 June), and returned to Puget Sound Navy Yard to serve in the Pacific Reserve Fleet for a year.

The seasoned ship set out from the navy yard and commenced her next assignment as the receiving ship at Naval Training Station San Francisco (24–27 April 1914). Returning north to Bremerton, St. Louis was again placed in the Pacific Reserve Fleet on 17 February 1916. Detached from that fleet on 10 July 1916, St. Louis sailed from Puget Sound on 21 July for Honolulu. Arriving at Pearl Harbor on 29 July, she commenced her next assignment as the tender for Submarine Division (SubDiv) 3, with additional duty as the station ship at Pearl Harbor, and helped to train the Hawaiian Naval Militia.

Just before World War I broke out, the Germans dispatched light cruiser Königsberg on a voyage that carried her to East African waters. As the war clouds loomed, Königsberg relieved German unprotected cruiser Geier, which had intermittently operated in that region, and Geier set out across the Indian Ocean for the German colony at Tsingtao [Qingdao], China. The fighting began while she steamed en route, however, and the ship eluded Allied patrols and slipped into Honolulu in October 1914, where she was subsequently interned.

German reservists and agents surreptitiously utilized the ship for their operations, and the Americans grew increasingly suspicious of their activities. Emotions ran hot during the war and the Germans violated “neutrality,” Lt. (j.g.) Albert J. Porter of the ships company, who penned the commemorative War Log of the U.S.S. St. Louis, observed, “with characteristic Hun disregard for international law and accepted honor codes.” Geier, Korvettenkapitän Curt Graßhoff in command, lay at Pier 3, moored to interned German steamer Pomeran, when a column of smoke began to rise from her stack early on the morning of 4 February 1917. The ship’s internment prohibited her from getting steam up, and the Americans suspected the Germans’ intentions.

Lt. Cmdr. Victor S. Houston, St. Louis’ commanding officer, held an urgent conference on board the cruiser at which Cmdr. Thomas C. Hart, Commander SubDiv 3, represented the Commandant. Houston ordered St. Louis to clear for action, and sent a boarding party, led by Lt. Roy Le C. Stover, Lt. (j.g.) Robert A. Hall, and Chief Gunner Frank C. Wisker. The sailors disembarked at the head of the Alakea wharf, and took up a position in the second story of the pier warehouse. Soldiers from nearby Schofield Barracks meanwhile arrived and deployed a battery of 3-inch field pieces, screened by a coal pile across the street from the pier, from where they could command the decks of the German ship. Smoke poured in great plumes from Geier and her crewmen’s actions persuaded the Americans that the Germans likely intended to escape from the harbor, while some of the boarding party feared that failing to sortie, the Germans might scuttle the ship with charges, and the ensuing blaze could destroy part of the waterfront.

The boarding party therefore split into three sections and boarded and seized Pomeran, and Hart and Stover then boarded Geier and informed Graßhoff that they intended to take possession of the cruiser and extinguish her blaze, in order to protect the harbor. Graßhoff vigorously protested but his “wily” efforts to delay the boarders failed, and the rest of the St. Louis sailors swarmed on board. The bluejackets swiftly took stations forward, amidships, and aft, and posted sentries at all of the hatches and watertight doors, blocking any of the Germans from passing. Graßhoff surrendered and the Americans rounded-up his unresisting men. 1st Lt. Randolph T. Zane, USMC, arrived with a detachment of marines, and they led the prisoners under guard to Schofield Barracks for internment.

Wisker took some men below to the magazines, where they found shrapnel fuzes scattered about, ammunition hoists dismantled, and floodcocks battered into uselessness. The Germans also cunningly hid their wrenches and spans in the hope of forestalling the Americans’ repairs. Stover in the meantime hastened with a third section and they discovered a fire of wood and oil-soaked waste under a dry boiler. The blaze had spread to the deck above and the woodwork of the fire room also caught by the heat thrown off by the “incandescent” boiler, and the woodwork of the magazine bulkheads had begun to catch. The boarders could not douse the flames with water because of the likelihood of exploding the dry boiler, but they led out lines from the bow and stern of the burning ship and skillfully warped her across the slip to the east side of Pier 4. The Honolulu Fire Department rushed chemical engines to the scene, and the firemen and sailors worked furiously cutting holes thru the decks to facilitate dousing the flames with their chemicals. The Americans extinguished the blaze by 5:00 p.m., and then a detachment from SubDiv 3, led by Lt. (j.g.) Norman L. Kirk, who commanded K-3 (Submarine No. 34), relieved the exhausted men.

The Germans all but wrecked Geier and their “wanton work” further damaged the engines, steam lines, oil lines, auxiliaries, navigation instruments, and even the wardroom, which Porter described as a “shambles.” The United States Navy nonetheless refitted Geier for service, renamed her Schurz on 9 June; and commissioned the prize on 15 September 1917, Cmdr. Arthur Crenshaw in command. The warship escorted Allied vessels and during one such voyage shaped a course from New York for Key West, Fla., on 19 June 1918. At 4:44 a.m. on 21 June, merchant ship Florida rammed Schurz on the starboard side, southwest of Cape Lookout lightship, N.C. The collision crumpled the starboard bridge wing, slicing into the well and berth deck nearly 12 feet, and cutting through bunker no. 3 to the forward fire room. One of Schurz's crewmen was killed instantly, and 12 others injured. The survivors abandoned ship and Schurz sank about three hours later. Schurz was stricken from the Navy list on 26 August 1918.

St. Louis meanwhile lay at Honolulu during the morning watch on 6 April 1917, when she received the electrifying news of the United States’ entry into World War I. The crew immediately began making the ship ready for battle, and the next day seven officers and 15 enlisted men of the Hawaiian Naval Militia reported on board to augment the crew, followed by 21 more militiamen in what Porter glowingly termed “fighting trim” on 8 April. The ship coaled and took on stores, and set out for the war in barely 72 hours during the late afternoon on 9 April to join cruisers that escorted convoys bound for European waters. She steamed through serene seas and at 3:30 p.m. on 17 April stood in to San Diego. The ship was placed in full commission, and three days later a detachment of nine officers and 315 enlisted men of the California Naval Militia reported on board, followed by a draft of 203 men from Great Lakes Naval Training Station, Ill., on 22 April, en route to San Diego (Armored Cruiser No. 6), and a further draft of 76 men from Frederick (Armored Cruiser No. 8), together with a consignment of stores.

The ship set out on the morning of 24 April 1917, but en route received a wireless message that collier Brutus ran aground on the west side of Cerros Island [Isla de Cedros], off the coast of Baja California. St. Louis hastened to render assistance and discovered refrigerator ship Glacier standing by. The cruiser’s crewmen passed lines to the sailors of the stranded ship, and a working party boarded and jettisoned coal. On the morning of 26 April, Frederick stood up, and St. Louis passed the lines to her. Brutus was refloated ten days later and taken in tow to San Diego for limited repairs, and she then completed extensive repairs at Mare Island Navy Yard.

St. Louis resumed her voyage and anchored at La Paz, Mexico, on 29 April 1917, where Capt. George W. Williams and Lt. E. F. McCain, who had been transferred from Frederick at the scene of the Brutus grounding, shifted to Pueblo (Armored Cruiser No. 7). St. Louis steamed following wartime precautions “darkened” and with war watches stationed, and reached Balboa at the Panama Canal Zone on the morning of 9 May. There the ship received orders assigning her to the Fourth Squadron, Patrol Force, to be based at Key West in readiness for an expected hunt for enemy raiders. The cruiser completed repairs, and then (10:55 a.m.–6:34 p.m. on 20 May) passed through the canal and anchored at Colón. The ship’s company “rushed” coaling, and she set out again the following morning. While en route to Key West St. Louis received orders directing her to Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic, and then further orders to make for Cuban waters.

The ship fired her first shot of the war while en route to Santiago de Cuba, at 2:03 p.m. on 23 May 1917. German commerce raider Seeadler, Kapitänleutnant Felix von Luckner in command, wreaked havoc with Allied ships. Formerly U.S. full-rigged ship Pass-of-Balmaha, she proved successful as a raider in large measure because of her sailing rig, which repeatedly enabled Seeadler to surprise her victims. The raider prowled in South American waters and then temporarily disappeared from Allied intelligence. St. Louis lookouts therefore grew suspicious when they sighted a three-masted schooner on the port beam, but the vessel failed to display colors or answer recognition signals. The cruiser’s crew manned their battle stations, and signaled the stranger to heave to but the windjammer disregarded the directive. Chief Gunner Wisker fired a single blank round from the saluting gun across the ship’s bow and she immediately cooperated, and St. Louis sent a boarding party that investigated the vessel and identified her as Gwendolyn Warren out of Bridgetown, Barbados, and permitted her to proceed. Seeadler continued her hunt into the Pacific but wrecked on a reef at Mopeha in the Society Islands on 2 August. St. Louis, meanwhile, reached Santiago de Cuba, Guantánamo Bay, and Nipe Bay [Bahía de Nipe], Cuba, and altogether embarked nine officers and 410 enlisted men of the 7th, 17th, 20th, 43nd, 51st, and 55th Marine Companies and transported them to Philadelphia Navy Yard, arriving on 29 May.

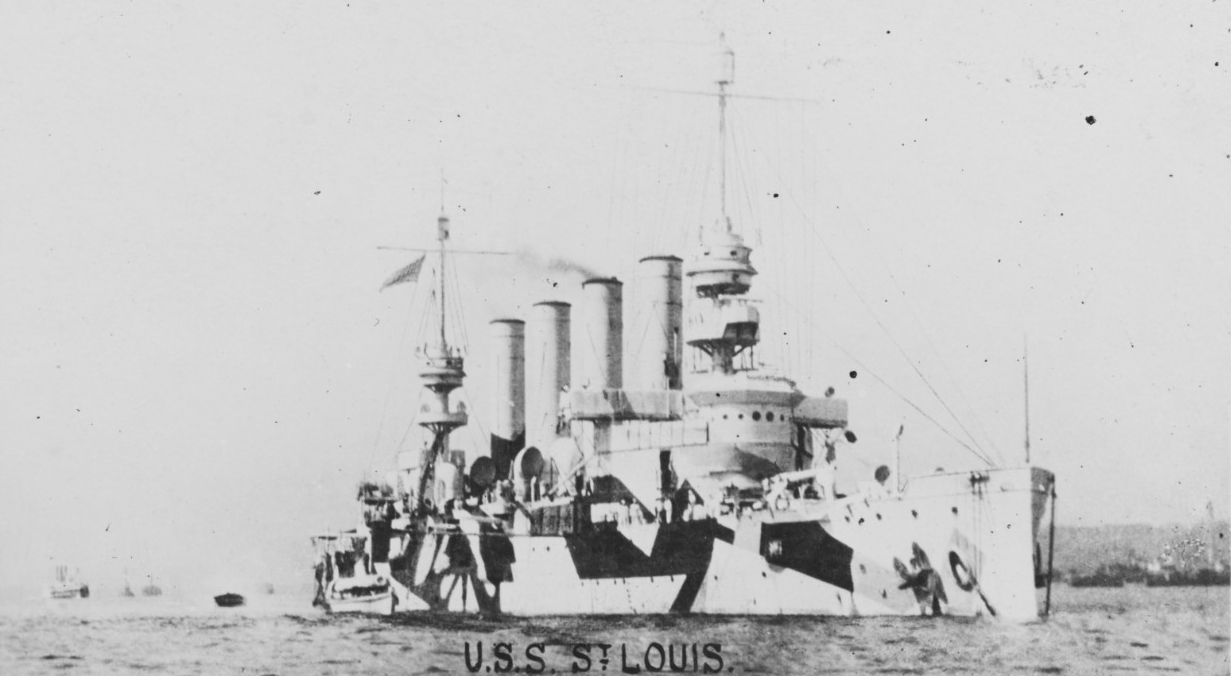

Several new officers reported on board St. Louis while she stayed at the yard, and workers overhauled the engines and auxiliaries. Two 3-inch antiaircraft rapid-fire rifles were installed, and No. 1 and No. 2 3-inch guns were removed from their old locations and placed on the superstructure deck forward, and the fire-control voice tubing was improved. St. Louis stood down the Delaware River and then set a northward course on 9 June 1917, and the following day anchored off Robbins Reef light near New York. She swung there until 17 June, the eventful day the ship sailed on her first convoy duty in escort of Group 4, American Expeditionary Forces.

Vice Adm. Albert Gleaves, Commander Cruiser and Transport Force, who had commanded St. Louis a decade before, led the ships that carried the soldiers and marines into the war, which sailed in four groups from New York bound for St. Nazaire, France, beginning on 14 June 1917. Group 4 consisted of cargo ships Dakotan (Id. No. 3882), El Occidente (Id. No. 3307), Edward Luckenbach (Id. No. 1662), and Montanan, escorted by St. Louis, troop transport Hancock, and Ammen (Destroyer No. 35), Flusser (Destroyer No. 20), Parker (Destroyer No. 48), and Shaw (Destroyer No. 68). The convoy at night sometimes presented an eerie prospect as the shadowy ships zigzagged through the rolling swells, collisions ever imminent should vigilance and skill relax, or the tense moonlit moments that exposed the ships to the stalking German U-boats (submarines). The group and its escorts nonetheless reached St. Nazaire without incident on 2 July.

St. Louis returned to Boston Navy Yard, Mass., for repairs on 19 July 1917. Following that work, she faithfully completed six additional voyages escorting convoys from New York bound for British and French ports. During one such journey to Brest, France (4–13 December 1918), the cruiser transported a section of a commission led by Edward M. House, commonly referred to as Colonel House, who advised President Woodrow Wilson during the Peace Conference at Versailles, France.

After the Armistice, St. Louis carried 8,437 men returning from Brest to Hoboken, N.J., in seven round-trip crossings (17 December 1918–17 July 1919), when she arrived at Philadelphia Navy Yard for repairs. The ship steamed more than 120,000 miles during the war, helped shepherd over 100 ships in eight outward bound convoys to European waters, and trained to efficiency more than 1,250 men for Navy Armed Guard and other duties. St. Louis was reclassified to a heavy cruiser (CA-18) on 17 July 1920.

Tumultuous events erupted during the fall of the Russian and Ottoman Empires and the ensuing Russian Civil War and the Turkish War of Independence, and St. Louis received notification that she was to deploy to Europe. The ship accordingly set out from Philadelphia for Sheerness, England (10–26 September 1920), where she disembarked military passengers. The cruiser then passed through the Strait of Dover and the English Channel to Cherbourg, France, and resumed her voyage through the Strait of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean to Constantinople [Istanbul], where she reported to Rear Adm. Mark L. Bristol, Commander, Naval Forces in Turkish Waters, on 19 October.

The ship primarily supported two humanitarian relief operations — to assist the Armenians and Russians. The American Committee for Relief in the Near East, more commonly known as the Near East Relief, was formed in 1915 to alleviate the sufferings of the oppressed Armenians and Syrians at the hands of the Ottoman Turks, and began pouring in supplies purchased from contributions taken up in the United States. St. Louis protected some of the cargo ships that carried these supplies, and the people who unloaded and distributed the aid.

On the northern shore of the Black Sea the struggle between the Bolsheviks and those who opposed them (often known as the “Reds” and “Whites”, respectively), drove large numbers of Russian soldiers and civilian refugees, who could expect no mercy from the Bolsheviks, into the Crimean Peninsula. Apparently at Bristol’s suggestion, Rear Adm. Newton A. McCully, a U.S. member of the Commission on Naval Terms detached from London, England, and a party of naval officers and enlisted men, including Lt. Cmdr. Hugo W. Koehler, were sent into Southern Russia early in 1920 on a special mission for the State Department for the purpose of keeping the government informed of developments in that region. Ships of the detachment transported the men, and a destroyer operated along the northern Black Sea coast to assist them, enabling McCully to continuously maintain mail and radio communication. Bristol dispatched Lt. Cmdr. Hamilton V. Bryan to serve as McCully’s agent at Odessa in the Ukraine, and he also kept Bristol informed of happenings.

One of these ships, destroyer Overton (DD-239), lay at Sevastopol when the Bolsheviks defeated Baron Peter N. Wrangel’s White Army in the Crimea in November 1920. Overton distributed relief supplies, provided transportation and communication services, and relocated refugees. A single ship could not cope with the massive influx of desperate people fleeing the fighting, however, and the Americans furthermore feared for the safety of their people trapped in the war. Upon receiving a message from McCully, Bristol sent Fox (DD-234), Humphreys (DD-236), John D. Edwards (DD-216), and Whipple (DD-217) from various operations in the Black Sea to the Crimea to assist evacuating people. The Americans nonetheless required additional ships and cabled for reinforcements including St. Louis.

Standing up the Bosporus from Constantinople on 13 November 1920, St. Louis rendezvoused with destroyer Long (DD-209), and U.S. steamships Faraby and Navahoe, and the four vessels worked with other ships to rescue the Americans authorized by McCully to escape. Besides McCully’s party, the ships pulled out U.S. consuls and their archives, representatives of the American Red Cross and Y.M.C.A., relief workers from other agencies, and numbers of Russian refugees from Sevastopol and Yalta in the Crimea, Novorossiysk, Russia, and Odessa. St. Louis returned her evacuees to Constantinople on 16 November. The following day, her crew formed boat landing parties to distribute food among refugees quartered on board naval transports anchored in the Bosporus. Wrangel meanwhile moved nearly 150,000 Russian refugees and crewmen on board 80 former Imperial Russian Black Sea Fleet ships and merchantmen into exile, initially to the harbor at Constantinople. Bryan supervised sailors and marines, including those from St. Louis, who helped care for these people, until many of the exiles sailed for Bizerte, Tunisia.

St. Louis turned her prow from Turkish waters on 19 September 1921. She called at Naples, Italy, and then at Gibraltar, and, fittingly on the third anniversary of the Armistice on 11 November, arrived at Philadelphia Navy Yard. There, on completing a pre-inactivation overhaul, she was decommissioned on 3 March 1922. St. Louis lay in reserve until stricken from the Navy list on 20 March 1930, and her hulk was sold for $37,444,42 for scrapping on 13 August in accordance with the provisions of the London Treaty for the limitation and reduction of naval armament.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. Nathaniel R. Usher | 18 August 1906 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Benjamin F. Hutchinson | 4 April 1908 |

| Cmdr. Albert Gleaves | 21 April 1908 |

| Lt. Cmdr. William V. Pratt | 5 November 1909 |

| Lt. George T. Pettengill | 2 April 1910 |

| Lt. Walter E. Whitehead | 5 April 1911 |

| Lt. Merlyn G. Cook | 18 March 1912 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Victor S. Houston | 1 January 1915 |

| Capt. Martin E. Trench | 29 April 1917 |

| Capt. Waldo Evans | 14 October 1917 |

| Capt. Amon Bronson Jr. | 13 July 1918 |

| Capt. Gatewood S. Lincoln | 6 September 1918 |

| Capt. David E. Theleen | 7 October 1919 |

| Capt. William D. Leahy | 31 May 1921 |

Mark L. Evans

9 January 2018