Segundo (SS-398)

1943-1970

Named for a Cavalles fish of Caribbean waters.

(SS-398: displacement 1,526 (surfaced); 2,391 (submerged); length 311'8"; beam 27'3"; draft 15'3"; speed 20.25 knots (surfaced); 8.75 knots (submerged); complement 66; armament 1 5-inch; 1 40 millimeter; 1 20 millimeter; two .50 machine guns; 10 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Balao)

Segundo (SS-398) was laid down on 14 October 1943 at Portsmouth N.H., by the Portsmouth Navy Yard; launched on 5 February 1944, sponsored by Mrs. Priscilla Sullivan, wife of Assistant Secretary of the Treasury John L. Sullivan; and commissioned on 9 May 1944, Lt. Cmdr. James D. Fulp in command.

Segundo got underway on 19 May 1944 under her own power for the first time and moved to Lower Harbor, Portsmouth, for two days of cleaning ship, dry dives, and drills. On 24 May, inspected by the Board of Inspection and Survey and declared completed all on the same day, she made her first timed dive on the 25th.

On 10 June 1944, she steamed for Newport, R.I., where she fired 30 torpedoes for contract trials. On 14 June, she arrived back at New London, and the next day underwent training, eventually firing six torpedoes and all of her guns. Segundo then went into the marine railway the Submarine Base, New London, to have her torpedo tubes and shutters inspected.

Segundo departed New London, Conn., on 26 June 1944 for Pearl Harbor, T.H., via the Panama Canal, and arrived at Balboa on 5 July. Sound tested in the Gulf of Panama on 7 July, Segundo departed Balboa and steamed for Pearl Harbor, arriving safely on 25 July. She received voyage repairs and on 30 July commenced one final training period out of Pearl, which lasted until 18 August. The submarine spent seven days during this period in special experimental exercises for training within a submarine wolfpack. In total, she expended seven torpedoes at her targets and test-fired her guns.

On 21 August 1944, the boat departed Pearl Harbor for her first war patrol accompanied by Seahorse (SS-304) and Whale (SS-239), making up an attack group known as “Wilkins Bears.” The three submarines conducted training dives, drills, and practice approaches daily. “Wilkins Bears” arrived in Tanapag Harbor, Saipan, on 3 September, and received fuel and supplies from the submarine tender Holland (AS-3).

Segundo delivered the operation plan to Hardhead (SS-365) off Surigao Strait on the night of 8 September 1944, and the following day arrived in the waiting area with orders to conduct surface or submerged patrol, attack small forces at once, and to send contact report before attacking large forces.

Four days later, Segundo maintained contact with an U.S. task force made up of two Essex-class carriers, one Independence-class small carrier, one cruiser, plus a number of destroyers that delivered air strikes against the eastern Philippine coast, “A very embarrassing position for us to be in,” wrote the commanding officer in the patrol report. The next morning, Segundo became a victim of misidentification when two U.S. aircraft suddenly appeared headed straight at her with guns blazing, but their shots fortuitously fell short just as she dived beneath the sea.

As a part of Offensive Reconnaissance Group “Zoo” on 14 September 1944, the group consisted of 13 submarines forming a scouting line between the Palau Islands and Nansei Shoto [Ryūkyū Islands] to report and intercept any enemy force attempting to hamper U.S. occupation of the Palau Islands. After making no contacts, on 24 September Segundo joined a coordinated attack group that consisted of Trepang (SS-412) and Razorback (SS-394). She then proceeded to her patrol area in the Luzon Strait and the upper part of the South China Sea on 1 December. The attack group, or pack, became known as “Roy’s Rangers,” under the command of Cmdr. Roy M. Davenport, commanding officer of Trepang.

On duty in Luzon Strait (25 September–9 October 1944), Segundo sailed into the upper part of the South China Sea, “a very uneventful patrol” during which she found no ships worthy of torpedo fire, and thus made neither torpedo nor gun attacks. “We were troubled a great deal by radar equipped night flying planes,” and Segundo managed to dodge a bomb from a Kawanishi H6K flying boat [Mavis] that caught them on the surface in the daytime.

On 10 October 1944, Segundo steamed to her station at Majuro Atoll, Marshall Islands, and arrived there on 21 October to end her first patrol. She immediately reported to Commander Submarine Squadron (ComSubRon) 14, and Commander Submarine Division (ComSubDiv) 141 for refit. Her refit was accomplished by submarine tender Bushnell (AS-15), and a relief crew from SubDiv 142. Combat insignia was not awarded for the patrol, but she received a star for her Asiatic-Pacific area ribbon for the Western Carolines Operation.

Officers and crew spent two enjoyable weeks at Myrna Island for rest and relaxation. When the crew returned to Segundo, they found it “spick and span” and in great condition. After two full days of getting her squared away for underway duty, the next five required intensive training, that consisted of submarine rescue ship Florikan (ASR-9) and light minelayer Ramsey (DM-16) acting as target ships. Segundo expended three exercise torpedoes and all of her guns in the realistic training exercise.

Segundo got underway on 16 November 1944 for her second war patrol. Assigned to the Luzon Strait and South China Sea, she conducted unrestricted submarine warfare within her area of operation. Despite a total of nine ship contacts, only one developed into an actual attack. This occurred on the evening of 6 December when all three vessels of “Roy’s Rangers” made a coordinated and well-executed strike on a large Japanese convoy, sinking all seven of the seven merchant vessels in the convoy. Escorted by enemy destroyer Kuretake and submarine chaser Ch-33 in the South China Sea, Segundo made two night surface attacks against Japanese convoys resulting in the damaging of Yasukuni Maru (later scuttled by her crew), Shinto Maru, and Kenjo Maru. U.S. aircraft strafed and later sank Shinto Maru, while Trepang torpedoed and finished off Kenjo Maru, sending her to the bottom the next day.

Typhoon-like winds measuring 8 on the 12-point Beaufort scale buffeted Segundo on 9 December 1944. A large wave washed F1c George H. Saunder overboard, and despite the best efforts of the crew, he was never found and was listed as Missing in Action. Serving on his first war patrol with Segundo, Saunder became her first casualty of the war. At 2330 all hands not on watch attended a short burial at sea service for their lost shipmate.

By 13 December 1944, the winds continued to blow strong and, “skies are overcast for [the] seventh straight day.” With the loss of F1c Saunder still fresh in the minds of the crew, every possible precaution to keep the men going topside on watch safe was attempted. Equipped with water tight flashlights, whistles, and life-belts, as well as a line secured to the man working the grease gun, the men “got good and wet,” and even lost a gun over the side at one point, but “suffered no harm” to themselves. The whistles were completely voluntary, but most of them put one around their necks before going on the bridge. The ship’s corpsman administered brandy to warm them up after they came off watch.

Segundo became caught in the middle of Typhoon Cobra on 16 December 1944, which ensnared Task Force 38 only 300 miles east of Luzon in the Philippine Sea. With high sustained winds of 145 mph and occasional gusts of up to 185 mph, TF 38 lost destroyers Hull (DD-350), Monaghan (DD-354), and Spence (DD-512). The war patrol report for the day notes “Light airs, nearly calm sea, all the stars are out; most unusual weather.” By 0530 that morning, a drastic change overtook Segundo: “Very abruptly the north monsoon descended again. Inside of half an hour the sea increased to state six and the rains came.” She submerged for the day at 0655 at zero visibility and would not surface until 1810 that night. On 17 December, she followed the same pattern, submerging in the early morning, and surfacing around 1800, to find no change in the weather. At 2107, an electrical fire broke out in a starter panel in the No. 1 vapor compression still in the forward engine room. The fire was under control by 2110.

At 1812 on 12 December 1944, Segundo received orders from ComSubPac to join Pack No.14, under the command of Cmdr. Vernon L. “Rebel” Lowrance, on 20 December. The weather still had not improved by the next day, with overcast skies, and the odd phenomenon of passing “through a rain squall about every ten minutes.” At 1940, the commanding officer decided to exercise the crew at battle stations in rough seas, and after diving down to 40 feet, noted depth control became very difficult. Securing from battle stations at 2025, Segundo exchanged recognition signals and call signs with Sea Robin (SS-407), one of “Rebel’s Rogues,” with whom Segundo would work with for the next few days.

After arriving at her rendezvous on 21 December 1944, four days before Christmas, Segundo joined the rest of “Rebel’s Rogues.” She formed a scouting line with Sea Robin, Sea Dog (SS-401), and Guardfish (SS-217), and arrayed themselves at intervals of ten miles between ships, no easy task considering the typhoon-like conditions still raging, and the night was dark and overcast. Segundo operated as the westernmost boat of the wolfpack and at 0007, sighted a submarine at 300 yards. Going to flank speed, she put her stern toward and “had the satisfaction of seeing him cross our wake about 200 yards astern on a 90-degree port track.” In an ideal situation for a torpedo shot, good sense took over when it was “plainly apparent” that “this one was a product of the U.S.A.” Thought to have been either Sea Robin or Sealion (SS-315), all attempts to exchange calls via SJ radar were unsuccessful. The near collision with the friendly submarine was dismissed, and at 0330 orders were received releasing Segundo from scouting line and duties with “Rebel’s Rogues.”

Continuing to sail through particularly rough seas with crests up to 40 feet on 26 December, one particularly large wave crashed over Segundo unexpectedly, and the great amount of water damaged both master and auxiliary compasses.

Four days later, Segundo proceeded north across the Bashi Channel toward her patrol station to Kasho To, not far from Formosa [Taiwan]. Two decoded messages arrived at 1910, both of great importance. The first was a contact report from Razorback, and the second contained orders from ComSubPac for both boats to rendezvous at a designated area near Formosa by 1500 on 1 January 1945.

The contact report from Razorback interested Lt. Cmdr. Fulp immensely. Evidently, she had sighted a Japanese convoy around sunset, and the enemy’s position put Segundo 120 miles north of the group. After plotting a course that would put them in the best position for an ambush, Segundo came to course 160 degrees at 15 knots to arrive at the predicted position of the convoy by 2400. Then at 1950, Fulp attempted to get verification from Razorback of the contact. Nothing was heard back until 2248, when Razorback reported the attack was completed, the enemy scattered, and she was complying with ComSubPac’s orders to clear the area.

Shortly after 2300, Razorback reported having fired 22 torpedoes and sinking or damaging four Japanese ships out of a total of six. Although it appeared that Segundo had missed quite a show, she continued onward to the proposed interception point, “not having anything better to do,” and asked Razorback for more information on the remnants of the convoy. At 0035, disappointment set in when Razorback replied that she lost contact at 2200 with the remaining enemy ships. Fulp later reasoned the convoy must have headed for nearby Garanbi, not Bashi Channel, and that if he had ordered a course for Garanbi to begin with, Segundo may have been “able to render some assistance [to Razorback].” Disappointed, the skipper set a new course to comply with ComSubPac’s orders and made 14 knots into rough seas.

On 31 December 1944, at 1901, a report came in of a Japanese patrol boat in Segundo’s vicinity. Alongside Razorback, both submarines began looking for the enemy vessel, but at 2354, orders came through from ComSubPac for the two boats to proceed to Guam for refit, along with routing instructions. Razorback and Segundo broke off from the hunt and set course for Guam.

Cmdr. Fulp ordered the crew to complete three training dives on the morning of 3 January 1945. He also noted Segundo enjoyed the “first good weather we’ve had in 34 days.” The next day, she completed three more training dives, and on 5 January, the boat arrived at Guam, where submarine tender Apollo (AS-25) and SubDiv 282 Relief Crew Number One accomplished the refit. The crew of Segundo spent an “excellent recuperation” at Camp Dealey and “made it almost luxurious.”

On 1 February 1945, Segundo got underway for her third war patrol, forming a coordinated attack group with Sea Cat and Razorback. On 6 February, their radar detected Yaku Shima at 0345. At 0605, Segundo dove for the day and surfaced while transiting the Colnett Strait, followed by Razorback and Sea Cat at 15 minute intervals. During the night, at 2320, a patrolling submarine was picked up by Segundo’s sonar crew. The skipper figured the midget had spotted and tailed them for some time since his crew had not. Able to shake them off by increasing speed to 15 knots, he passed word to Razorback and Sea Cat so they could avoid being seen.

Razorback reported making contact with the enemy at 0000 on 15 February 1945, but 20 minutes later the report was cancelled having proved false. At 0030, Sea Cat reported a contact of three small targets at a range of 10,000 yards. Segundo adjusted her course in order to gain position on the flank opposite of Sea Cat, and picked up three small pips on radar at a range of 11,600 yards. However, a heavy rain with dense cloud cover gave Fulp pause. He began to doubt his radar equipment, but went ahead and ordered his crew to battle stations at 0117.

A minute later Segundo received “Am attacking” from Sea Cat, although she never transmitted her course or speed. At 0146, three explosions were heard, spaced at 11 or 12 seconds apart. At 0203, Sea Cat reported her attack complete, but a skeptical Fulp wondered if the attack had been for naught. “It appeared ships were not suitable torpedo targets; Sea Cat was not able to identify them.” At 0235, he ordered Segundo’s crew to secure from battle stations, keeping tracking stations manned just in case, until these were also secured by 0250. By the end of the same day, at 2145, the pack was assigned new patrol stations that would take all three ships near Taiwan.

Upon reaching her assigned area of operations on the night of 16 February 1945, Segundo patrolled submerged during the day and surfaced at night, owing to a temporarily out of commission SJ radar. Visibility at night was exceptional and estimated that heavy ships could be seen at a range of 25,000 yards. At 2040 hours, a lookout sighted a ship with a small port angle on the bow headed in an easterly direction toward Segundo. As the vessel drew nearer, she was determined to be an enemy destroyer. Fortunately the SJ radar began working while tracking her began. Fulp noted the enemy’s peculiar actions, which indicated the destroyer was an advance screen for more important units yet unseen. He held off an attack and continued to lie in wait for bigger fish.

At 2330, Razorback made radar contact on the Japanese warship and sent a contact report asking if it was Segundo. Wishing to avoid unnecessary radio transmissions, Fulp had not reported Segundo’s location or the presence of the Japanese ship. However, in order to avoid Razorback firing on the destroyer and ruining the ambush he was intending to spring, he sent a single word reply, “negative.”

Cmdr. Fulp noted that at 0030, the destroyer that had been lying to the east resumed course eastward and then came to a new heading at an increased speed of eight knots. In his estimation, “This confirmed our belief that he was an advance scout as he deliberately invited attack and made us conclude more than ever we should avoid detection.” The captain then noted by keeping his distance and focusing entirely on the Japanese vessel, he “almost ran down Razorback, who had evidently commenced an approach.” Still hoping to prevent giving away their presence, he sent a contact report to Razorback to “let her know we had had contact all along.” In a note Fulp included in the War Patrol Report, he added: “As Group Commander I hoped that Razorback would not attack, as one torpedo explosion would have given away the whole show. However, I did not give her any orders one way or the other. Razorback did not attack.”

After breaking contact with the enemy vessel, Segundo spent the rest of the night “tracking and avoiding one small contact after another,” all of which “gave the appearance of fishing trawlers or schooners.” As group commander, Fulp noted that “Up to now we have patrolled the main area as a pack, for a total of thirteen days, without making any worth while [sic] contacts.”

Concluding on 19 February 1945, that the area was no longer conducive to the pack-hunting strategy the task group had started the third war patrol utilizing, Fulp sent a message at 2130 to both Razorback and Sea Cat that they would begin to patrol in accordance with their back-up strategy, known as “Plan Baker.”

An independent cooperative ship patrol, “Plan Baker” divided the entire area into three sections, assigned to one boat for five days, and then rotating into another of the sections for the next five days, and so on. It did not require the pack to maintain their usual distance of fifteen miles apart as the previous plan, nor to act as a screen in order to prevent enemy ships from passing through. Fulp reasoned that “We gave the other plan a fair try without much success, now we can see how this one works out.” One can only speculate on the skipper’s bemused surprise, when at 2200, he received a report from Sea Cat indicating the three targets she fired at on the 15th had all sunk.

After making contact with a ship thought to be an enemy minelayer moving to the southeast on 21 February 1945, Segundo tracked the Japanese vessel and at one point closed-up to approximately 4,500 yards off her bow. She held back just as a medium-sized patrol boat closed in and the two exchanged signals by light. Although no mines were seen being laid, it appeared the enemy ship “was engaged in this activity.” By 1200, several smaller fishing boats were spotted in the vicinity and Segundo stopped tracking the vessel.

A floating mine was sighted approximately 20 feet off the port side on 3 March 1945, but due to it barely being visible above the waterline, it was thought best to be left alone. At 0618, a submerged patrol was begun west of Danjo Gunto. In accordance with the rules of the Geneva Convention, Segundo left the Japanese hospital ship Takasago Maru alone. At 2130, message number seven was sent to ComSubPac requesting a seven day extension in the area. Messages transmitted to Sea Cat and Razorback over the pack frequency apprised them of this request.

Segundo surfaced on 4 March 1945 at 1916 and noticed traffic “moving high up in the Korean Archipelago.” The commanding officer decided to revert back to patrolling as a pack, and sent directions to Sea Cat and Razorback, directing them to patrol sub-area 11, which was the area off the Korean coast.

During the night, the request to begin patrolling north for an additional seven days was approved by ComSubPac. Segundo’s commanding officer had originally requested to patrol in the area of the East China Sea, but received orders to patrol the Yellow Sea. After spending the majority of the day on 5 March 1945 navigating through a crowd of fishing boats, trawlers, and other smaller vessels, Segundo then began navigating through rough seas before making radar contact with an enemy ship at a range of 13,900 yards.

Fulp began tracking the enemy and increased his own speed to match the Japanese vessel at nine knots. At only 1,500 yards distance, Segundo was finally able to get a good look at her target. At 2355, the skipper ordered a spread of four torpedoes fired, the first shot at a range of 1,300 yards and the last at 1,100 with a depth setting of six feet. All the torpedoes missed, but the Japanese merchant vessel gave no indication of having sighted Segundo or the torpedo wakes. The exasperated captain could not believe he had missed. The solution of the torpedo problem “had checked perfectly.” A gun attack was briefly considered, but the seas remained rough. Fulp watched in frustration as the enemy merchantman sailed away unscathed.

Razorback sent a report that she had sunk two sea trucks and one schooner by gunfire and had taken on board three wounded POWs on 7 March 1945. Sea Cat also sent word that she sank a small cargo vessel and had requested permission to extend patrol into the Yellow Sea with Segundo. ComSubPac approved her request. At 0611, Segundo dove for a submerged patrol between Haku To and Tsushima Island. At 1235 she sighted six Aichi E13A Type 0 reconnaissance floatplanes [Jake] flying in column very close to the water on an obvious anti-submarine hunt, “probably a result of Razorback’s gun shoot yesterday.”

At 1317, an analysis of Segundo’s failed attack on the merchant vessel was determined to have been caused by “control errors.” The approach officer did not make clear to the assistant TDC operator how the spread was to be applied, with the result that both a point of aim spread and an offset spread were put on the torpedoes. The submarine fired three torpedoes at the enemy ships stem, and one abaft of her stern.

At 2240 Segundo made contact at 14,200 yards with the same merchant vessel she attacked unsuccessfully the night before. The cargo ship “was following almost exactly the same path, only reverse, that was used by the one last night.” Fulp decided against another attack, due to the enemy ship’s small size and the heavy swell then running. Seas were too rough to man the deck gun, and although they briefly considered unleashing the 40-millimeter gun, they also decided against doing so, as the crew entertained chances of something bigger to come along. However, she tracked this target until 0130 and tried without success to raise Sea Cat by radio.

By 0136, Segundo lost contact with the small Japanese vessel she had been tracking. At 1923 on 8 March 1945 she surfaced and headed for the Yellow Sea, to patrol in accordance with ComSubPac dispatch approving a request for a seven-day extension. At 1923, the submarine received a message from Tench (SS-417) claiming they would not be in relief position until 17 March. The commanding officer made the decision, based on that information, to continue the patrol into the East China Sea, diverting from the Yellow Sea because “We have become pretty well acquainted with the East China Sea, have a pretty good idea where the traffic is moving, and will be able to spend more time actually patrolling.” At 2200, Segundo attempted to radio Sea Cat to advise of the decision to remain in the East China Sea.

On 9 March 1945, at 2315, she made radar contact with a single ship at a range of 11,990 yards. The vessel was another small Japanese merchant bearing ten knots. While tracking the enemy ship, Segundo made sonar contact with a larger ship some 16,000 yards distant. This larger vessel was cruising at a slower seven knot pace and passed the first on an opposite course about 1,000 yards apart. At 0120, Segundo fired four torpedoes from her bow tubes at the bigger ship, a medium merchant vessel with a flush deck. All four missed.

Fulp chose to “attack on the surface to avoid having to dive in confined waters with strong currents.” Despite this, and the fact that Segundo was 2,000 yards from the armed merchant when they fired all four bow torpedoes at her, no return fire or retaliatory measures were taken. The captain deduced the enemy must not have “had any lookouts,” or thought “we were a fishing vessel.” Even less easy to explain were his torpedoes missing their target. The enemy vessel measured “at least 350 feet in length by binoculars and radar,” and all fire control data and gear were checked and found to be fine. “Assuming that no. 2 torpedo ran erratic, then no. 3 and no. 1 should have hit. Post-mortem plot shows that at least one and possibly three torpedoes should have hit.”

Frustrated once again with the lack of results, Fulp decided to dive before running the risk of being discovered out in the open, and gave the order for a submerged patrol. Segundo did not resurface until later in the evening, encountering upwards of 20 fishing vessels and sporadic enemy patrol boats upon resurfacing.

Segundo’s sonar made contact with a target cruising at 11 knots at a distance of 15,700 yards on 11 March 1945. As the boat tracked the target, one pip split into two smaller ones close together at a range of 11,000 yards. At 0337, Segundo stayed with the target that produced an even greater pip than those she was tracking. This new target was slower moving, making only nine knots, until she came within binocular sight at 8,000 yards.

At 0413, Fulp gave the order to fire, and four torpedoes were launched in a spread running towards Shori Maru, now only 1,500 yards away. The first and fourth torpedoes ran erratic, but the second struck the enemy vessel, blowing off her aft end in a terrific explosion, while the third struck amidships and tore the ship in two. Shori Maru disappeared in just two minutes. Three minutes later, another sonar contact at 14,500 yards consisting of four pips were identified, all approximately equal in size. A half-hearted “quest for POWs” of Shori Maru was quickly abandoned when this sudden contact was made.

At 6,000 yards these enemy vessels were identified as two medium transports and two destroyers or destroyer escorts. As Segundo moved into position to dive to radar depth for an attack, the convoy changed course to the right, passing north of Jaku To between Shori To and Kingo To. Segundo’s reloaded launch tubes carried three torpedoes forward and a full nest aft before a race against time began. As dawn began to break and the enemy convoy raced towards safe haven in the nearby islands, Fulp realized his chance to strike “was now or never,” and increased Segundo’s speed before giving the order to fire a deadly spread of four torpedoes.

Suddenly, the entire Japanese convoy changed course and charged straight for Segundo, obviously alerted to her presence from her previous attack on Shori Maru. Fulp dove in the midst of eight fishing schooners, but “heard six explosions just before diving.” At 1752, the crew heard about 12 distant explosions, and despite picking up the sound of screws to the south at 1914, surfaced at 2003. Despite these explosions, none of the enemy vessels in the convoy were apparently hit by the torpedoes fired from Segundo. At 2100, the skipper received orders to clear the area and set course for the south.

Segundo arrived at Pearl Harbor on 26 March 1945 to end her third war patrol.

Getting underway on 16 May 1945 and assigned to lifeguard duties in the East China and Yellow Seas, Segundo steamed ahead on her Fourth War Patrol. Two days later, while running on the surface in the East China Sea, she passed two bodies close aboard in the water. The crew determined one of the corpses was Japanese and the other American, both undoubtedly from their respective armed services, but there was no way to determine how they had wound up so far out to sea. The war report makes no mention whether the bodies were given a proper burial at sea or simply put back in the water.

After the high periscope watch sighted the first of five Chinese junks sailing too close to Segundo’s position south of Saishu To on 21 May 1945, a boarding party led by Lt. (j.g.) James McLaughlin and CTM Earl Russell searched the nearest junk. Finding only a few fish, some flour, and a quantity of “good Manila line,” the party seemed disturbed by the “obeisance and Kow-towing from the Chinese crew of eighteen men and one old crone.” Despite their uneasiness, McLaughlin provided the “funny scared lot” Spam [canned spiced meat], bread, cigarettes, and matches. The young officer ordered his men to search two of the other junks quickly, only to find the same conditions, before returning to Segundo.

Reaching her assigned station on 22 May 1945, Segundo unofficially became a submarine of “The Legionnaires” under the tactical command of two-time Navy Cross awardee Cmdr. William T. Kinsella in Ray (SS-271). The other ships making up Kinsella’s merry band were Sea Cat, Billfish (SS-286), Shad (SS-235), Scabbardfish (SS-397), and Balao (SS-285).

While on patrol in her sector off Korea a week later, Segundo surfaced early in the afternoon on 29 May 1945 to find six schooners in sight. Approaching the first two at a slow speed, her lookouts eyed them carefully and noticed how clean and freshly painted they appeared. Fulp was about to let the schooners continue on when Segundo passed the third and saw the Rising Sun flag painted on his bow. The crew manned their guns and fired warning shots. Instead of taking to the dinghies carried by each of the schooners, the crews “scurried below.” Segundo’s gunners destroyed the third vessel and began to look for Japanese flags on the two others. When no markings were found, the vessels were assumed to be Korean. Segundo went alongside to be sure. When one of Segundo’s gunners motioned for one of the vessels Korean crewmen to come onboard the submarine, “five or six got on board.” All were sent back except one, a Korean selected because it was thought he would be “well informed” about the Japanese in the area and “more inclined to part with his information.” Also, the man seemed “cleaner” and came on board “willingly and of his own accord.”

The information the man provided must have been very accurate because by the time Segundo left the two Korean vessels at 1429 and securing from battle stations at 1600, Segundo went into action, sinking or destroying seven additional Japanese schooners in the nearby area, “all of which bore Japanese markings and appeared to be manned by Japanese, and having inspected closely an equal number which bore no markings and appeared to be manned by Koreans.” Likely sailing between Korean and Japanese ports from a small boat building yard in Port Arthur [Lüshunkou District, China], a suspicion these schooners transported troops is noted in Segundo’s war patrol report, due to the crews of the schooners’ being “robust, stalwart, and young,” and also giving “one the impression that they were not sailors.”

Segundo spotted two enemy sailing ships and attacked on the evening of 31 May 1945. The attack began at 2250 on a four-masted, 225-foot long, four-rigged sailing vessel with gray sails making 3.5 knots. At a range of 3,000 yards, Fulp ordered tubes No. 5 and 6 to fire. About 30 seconds after the torpedoes launched, one hit was observed slightly abaft and the vessel immediately split into two parts and sank, with the exception of the forecastle and poop deck. The second torpedo missed, but the damage had been done. By 2335, contact with the second vessel could not be regained, and Segundo’s crew secured from battle stations.

At 0040 on 3 June 1945, Segundo encountered another four-masted sailing vessel, Anto Maru, in the East China Sea. After confirming she flew the Rising Sun, she set up for a surfaced attack run. The crew was called to battle stations at 0055, and the first torpedo ran hot at 0130. This missed by only 5 feet astern, and the gunners mates manned the 5-inch deck gun and both 40mm guns. At 0144, the gunners commenced firing both the deck gun and 40-millimeter guns at a range of 500 yards. The gunfire easily neutralized the topside enemy gun crew, while Segundo closed in for the kill. Fulp later stated he found the 40-millimeter guns to be “superb and wicked.” Although no fires were started from all the hits scored upon the enemy sailing ship, her stern settled beneath the surface and her bow rose high in the air. All of her masts except one were denuded, and although considered a total loss, she had been strongly built and been “surprisingly hard to destroy.” Just before the stern settled, one small boat was lowered into the war and a lone man “commenced sculling” away from his ship. Segundo dove and resumed patrol operations.

While maintaining her patrol off the coast of Korea on 7 June 1945, Segundo sighted another four-masted sailing vessel at 6,000 yards similar in appearance to the one she previously destroyed. Segundo’s crew manned their battle stations and made ready before overtaking the sailing vessel quickly at a range of only 500 yards, raking her topside with automatic weapons fire. The 5-inch deck gun “leisurely” completed the destruction of the target, while two of the enemy crew hurriedly abandoned ship. A third Japanese sailor “clambered onto what was left of the poop deck with a rifle, but a few bursts from the 20-millimeter discouraged him from using it.”

Fulp sailed into what he at first believed to be a trap on the night of 8 June 1945. Earlier that afternoon, just before 1500, sonar heard the “first of a long series of heavy distant explosions, which did not sound exactly like depth charges and were thought to have been submarine volcanic disturbances.” The sounds continued for about one hour. At 2032, Segundo surfaced and commenced transit of Gaichosan Suido toward Port Arthur, carefully avoiding any fishermen. At 2137, lookouts sighted two bright lights, which worried the skipper. The Chinese fishermen used single dim white lights, “but these did not look like fishermen’s lights.”

At 3,000 yards, lookouts then spotted what appeared to be a tow astern of the lights. With the night exceedingly dark, the men could not see much. “It looked like some sort of a trap,” the war diarist noted. After much deliberation, Cmdr. Fulp decided to treat the contact as a tug and tow and ordered them to be tracked. Just before giving the order to fire torpedoes, a door opened on the main deck level of the tug, which disclosed a brightly lit interior. Just as the first two torpedoes launched from the starboard side bow tubes, sparks belched up from the tugs stack, and she turned in an attempt to ram Segundo. Fulp ordered a sharp turn to port and went ahead at full speed. The tug missed Segundo’s stern by approximately 100 yards. Slowing to ten knots and coming about to 180 degrees, the skipper ordered a third torpedo fired. All three torpedoes missed. The enemy tug finally extinguished her lights, but continued to run slow at only 1.5 knots on no particular course.

At 0022 on 9 June 1945, Fulp pondered what course of action to take. The night “seemed to be too dark for gun action,” but he quickly realized “this was our only recourse.” The enemy vessels could barely be made out as blots on the horizon at 2,000 yards away in the darkness. Fortunately, the “tug” conveniently exhibited one very dim light amidships that could be seen with the naked eye at 1,000 yards. The commanding officer gave his gun crews 20 minutes to let their eyes adjust to the dark, and then went in for a gun attack at high speed.

When her gunners mates reported being able to see the target and range at 700 yards, Segundo turned right and brought all guns to bear, slowed course, and opened fire with all guns except the 20-millimeter at the “tug.” Fulp ordered the 20-millimeter gun crew to fire only upon the “tow.” As tracers from the 5-inch and 40-millimeter guns lit up the night sky around them, Segundo’s crew suddenly realized their targets were not a tug and her tow, but two Japanese patrol vessels.

The trailing ship almost immediately attempted to “pull a ramming act,” but Segundo veered hard a-port in time, with all guns bearing, and shifted fire of the 5-inch gun upon the ramming vessel. The 20 millimeter began to open up and “was doing a beautiful job of neutralizing this one single-handed.” As Segundo and the ramming vessel passed one another at only 75 yards, the 20 millimeter emptied its second magazine into the pilot house with few misses, setting it afire. A hit from the 5-inch gun promptly put the fire out by blowing the pilot house away.

After the first pass, the tug began to slowly sink by her stern, and the trailing vessel steered out-of-control. Segundo made two more passes at the trailing ship, firing all guns except the 40 millimeter because it ran low on ammunition. Both vessels desperately fired back at Segundo with what the Americans estimated were 37 millimeter guns or better -- most likely 20 or 25 millimeter -- their rounds noticeably falling short, sending large splashes of water upon the deck and bridge. Segundo delivered her “coup de grace” to both targets with her 5-incher. The enemy patrol vessels quickly sank. Segundo secured from battle stations at 0046 and at 0300 requested a new patrol station. Ordered to divert to the Yellow Sea area of operations as senior ship in the pack, Segundo, unaware of the whereabouts of her six sister boats, remained in the hunt. Only some 12 hours later she would come across her next contact.

At 1235, a ship appeared out of the haze, seeming almost “too good to be true.” Segundo tracked the Japanese ship and continued to match her speed at approximately four knots. The enemy vessel continued to present a large starboard angle, and Fulp closed up, but due to a navigation error, the approach officer realized they overshot the target. The escort ship remained just astern of the enemy vessel, when both suddenly zigzagged, putting them at a distance of 7,000 yards, outside the minimum 5,900 yard torpedo run range of an Mk.18 torpedo.

The commanding officer identified the enemy vessel as one of the newly-built Japanese freighter-transports of 7,500 tons, with masts reaching 70 feet high. Of greater importance and mystery was the freighter’s escort; described as a large destroyer or destroyer escort “with two gun mounts forward and a heavy, short, single stick mast,” Segundo’s war patrol noted this “could have been a TERUTSVKI [-class] destroyer,” possibly referring to the Japanese destroyer Teruzuki, sunk off Guadalcanal on 12 December 1943. The destroyer may have been of the Akizuki-class, but records indicate Suzutsuki the only Akizuki-class destroyer of the Imperial Japanese Navy to survive the war. Suzutsuki had suffered severe damage escorting battleship Yamato in her suicide run to Okinawa in early April.

Therefore, it is highly probable the destroyer encountered by Segundo in June 1945 had been one of the Fuyutsuki-class destroyers, a sub-class of the Akizuki design. Beginning in mid-1943, construction began on four ships of the Fuyutsuki-class, and all four survived the end of the war. The noticeable differences from the Akizuki-class, at least in physical appearance, were a simplified bow design and the removal of the rear deck house. These differences were subtle enough not to have been noticed by Segundo while headed in on her self-foiled attack run.

In a night surface attack on 11 June 1945, Segundo fired seven torpedoes and sank Japanese transport ship Fukui Maru with three. Despite not being visually able to see the target, due to heavy fog, Fulp solely relied on radar range and bearing information. Forty seconds after launching torpedoes, the crew “saw, heard, and felt three terrific hits.” Fukui Maru, estimated at 10,000 tons, “disappeared from radar scope three minutes after being hit, at a range of 2,000 yards and did not reappear.” Her escort ships circled twice, in a vain attempt to locate Segundo, steadied on a new course, slowed to six knots, and continued a zigzag pattern, “but otherwise did not bat an eyelash. If this is the old highly touted SAMURAI spirit, we want none of it, none at all.”

Segundo flooded down two feet to bring her no. 1 and no. 2 torpedo tubes underwater and “came in for attack at slow speed,” firing four torpedoes using radar bearings at depths set at five feet. All four missed because the target took drastic evasive maneuvers after the torpedoes passed underneath her hull. “It was tough luck to miss and we felt our usual chagrin at having wasted torpedoes.” Fulp, realizing Segundo had not had a navigational fix for 21 hours, and cruising in waters of 15 to 20 fathoms with patches of five, eight, and ten fathoms, decided to break off pursuit.

At 2332, Fulp received a dispatch from Paddle requesting Segundo transport a sailor with a bad fungus infection back to base. At 0528, Segundo brought CMoMM(AA)(T) Joseph E. Puckett, on board with an infection covering him from head to foot. Shoving off soon after, the boat soon spotted a floating mine at 0927 but left it alone after attempts to sink it with .50-caliber fire failed. At 2049 that same day, Segundo received orders from ComSubPac to proceed to Midway for refit. Ten days later, at 0930 on 21 June, she arrived at her destination, where, on 29 June 1945, Lt. Cmdr. Stephen L. Johnson relieved Cmdr. Fulp as Segundo’s commanding officer. After a refit and a brief but intense training period, she sailed from Midway to her patrol area in the Sea of Okhotsk on 10 August.

Segundo received word of the surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945, and then (18–23 August) patrolled outside the Kurile Islands chain awaiting orders. On 24 August she received orders to proceed to Tōkyō Bay and headed south.

Off the coast of Honshū on the early morning of 29 August 1945, Segundo picked up a radar contact. She trailed it at a distance of 4,000–5,000 yards, staying off its quarter. She identified the craft as a “large Japanese submarine” making 15 knots. When dawn arrived, she sent out the international signal to stop, which the enemy boat heeded. After some cautious negotiations, Segundo’s officers agreed that I-401 (Lt. Cmdr. Nambu Nobukiyo, commanding) should send over a boat. Since the Japanese had none on board, Segundo made ready her rubber boats. Lt. (j.g.) James Brozo and CTM Edward A. Russell paddled over to begin communications with the Japanese, and returned with Lt. Bando Muneo, the chief navigator.

The next 30 minutes consisted of Lt. Cmdr. Johnson, Segundo’s commanding officer, holding a “doubtful conversation with Bando in baby talk plus violent gestures.” Bando claimed I-401 was heading for Ominato for the surrender and “did not have sufficient fuel for the trip to Tokyo. This we doubted and eventually he agreed.”

The Japanese agreed to accept a prize crew on board, consisting of one officer and five men, and to proceed to Tōkyō Bay with Segundo. The formal surrender “was to take place at 1100 August 30” or when the boat reached Yokosuka. In return, the crew of I-401 would be allowed control of their ship. At 0755, Lt. Cmdr. Johnson received permission from ComSubPac to proceed with the seizure.

Lt. Bando accompanied the prize crew -- Lt. John E. Balson, CTM Russell, MoMM1c Ralph S. Austin, QM3c Carlo M. Carlucci, EM1c Kenneth W. Diekmann, and TME2c Jenison V. Walton -- who were to remain topside for the entire trip to Tōkyō Bay -- on board I-401 and began to speak very openly about his ship, once the largest submarine in the world, and the largest diesel submarine ever built, designed to carry three Aichi M6A1 Seiran float torpedo bombers. With an impressive dive time of 70 seconds, she could reach a maximum depth of 100 meters, and a cruising speed of 17.5 knots. Bando also claimed she could carry 200 men, something Lt. Balson and his men found difficult to believe (it was actually closer to 150). “This could quite possibly be an error on his part,” Segundo’s patrol diarist stated, “as I think the war interrupted his english [sic] instruction.”

At 0500 on the morning of 30 August 1945, the U. S. flag was raised on board I-401. According to Segundo’s war patrol report, at 0515 Balson, leader of the prize crew, sent word that, “a division commander [Capt. Ariizumi Tatsunosuke] had committed Hari Kari on board the I-401. Lt. Cmdr. Nambu had asked permission to bury him at sea. This was granted but no body [was] ever seen.” Capt. Ariizumi had commanded the submarine I-8 when she had brutally massacred the survivors of the Dutch steamer Tjisalak [26 March 1944] and U.S. freighter Jean Nicollet [2 July 1944].

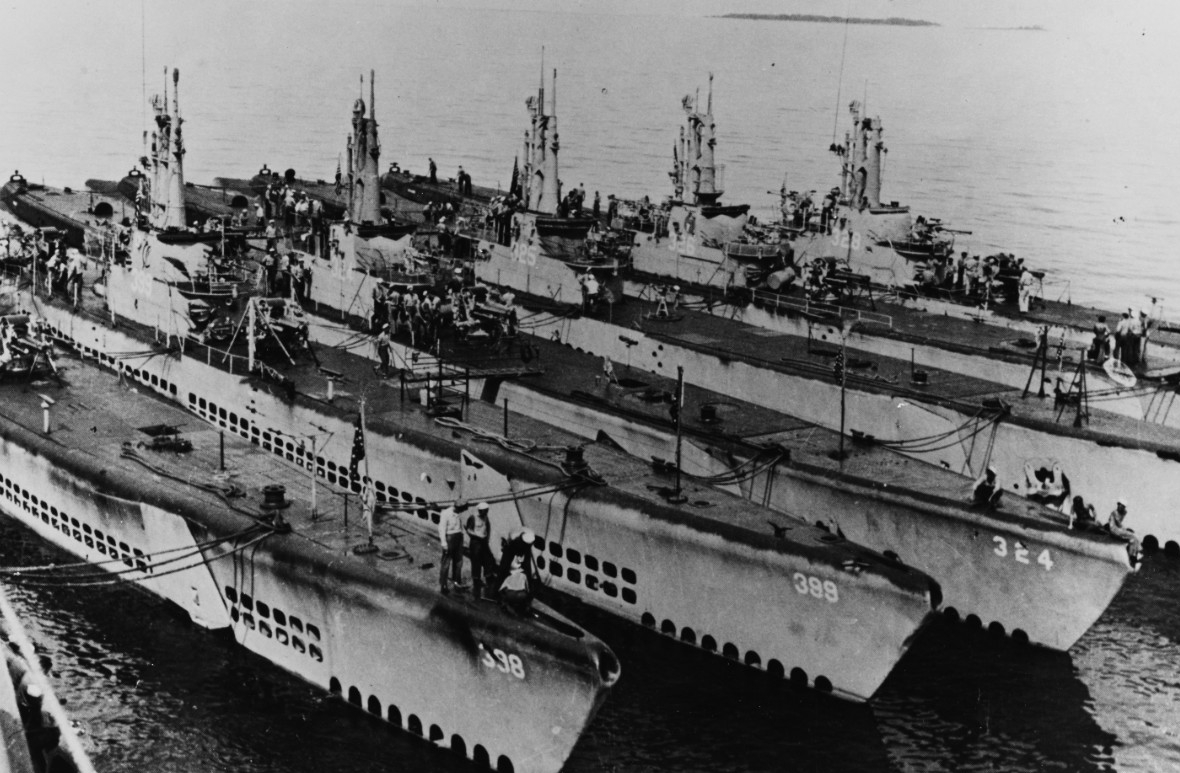

Upon arrival at Sagami Wan, the destroyer Gatling (DD-671) relieved Segundo of I-401, at which point Segundo proceeded to Tōkyō Bay and moored in a nest alongside the submarine tender Proteus (AS-19), enabling her to be present for the signing of the surrender documents by representatives of the Empire of Japan on board Missouri (BB-63). The war over, Segundo sailed for Pearl Harbor on 3 September 1945, in company with eleven other submarines. On 12 September, she arrived in Hawaii and three days later departed for Seattle, Wash., for leave, liberty, and recreation.

After Segundo received orders to Submarine Squadron Three (SubRon 3) based at San Diego, Calif., in late September 1945, she made a three month cruise to Australia and China, and then a trip to Acapulco, Mexico, followed by a four month cruise to China in late 1948. These marked her first peacetime voyages. Segundo received the Submarine Squadron Three Efficiency Pennant for Excellence in Performance of Duty for the year 1948.

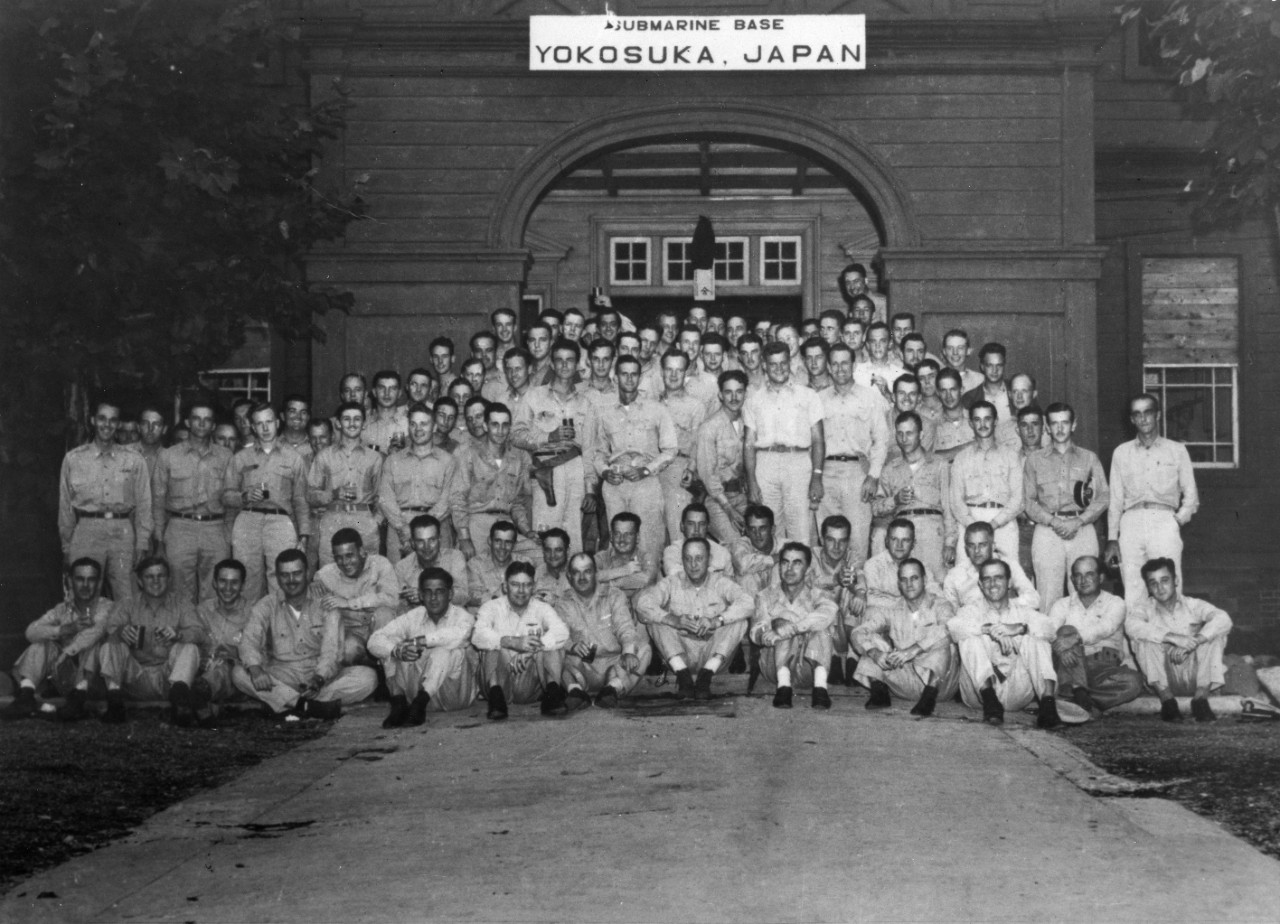

In March of 1949, she was converted to a Fleet Snorkel-type submarine, at San Francisco Naval Shipyard, Hunters Point, Calif. In 1950, she set out for the Philippines on a goodwill tour. After a brief stay there, she shoved off for Japan, arriving on 25 June 1950. Segundo spent the next few months conducting operations in the area off Japan, in support of United Nations Forces, North Korea invading South Korea in July, before returning to her home port of San Diego near the end of September 1950.

After a refit period and intensive training off the coast of San Diego, Segundo’s fourth cruise to the western Pacific began on 15 August 1952. Once again, she deployed to the Japanese area of operations in support of U.S. forces fighting communist units in Korea. During this lengthy deployment, she made port calls to Pearl Harbor; Yokosuka and Sasebo, Japan; Inchon, Korea; and Buckner Bay, Okinawa. Her last two deployments earned her the China Service, Korean Theater, and United Nations Medals.

Returning to her homeport of San Diego in February 1953, Segundo resumed her duties under operational control of Commander Submarine Flotilla One. From 3 May - 23 September 1953, she underwent an extensive overhaul at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, at Vallejo, Calif. After leaving the shipyard, she began workups and training exercises at sea before departing for her next deployment.

Segundo departed San Diego on 14 June 1954, en route for her extended operations in the western Pacific. Ports visited during this cruise included Pearl Harbor, Subic Bay, Philippine Islands; Yokosuka, Nagoya, Kobe, and Chichi Jima, Japan; Hong Kong; Taipei, Taiwan; and Buckner Bay. She returned to San Diego on 18 December 1954 and entered the shipyard for a refit period.

Leaving San Diego on 24 June 1955, Segundo proceeded to Mare Island Naval Shipyard for a regular overhaul period. The overhaul ended on 18 December and the next day Segundo began a shakedown cruise to Acapulco, Mexico, celebrating the New Year there and sailing home for San Diego on 20 January 1956.

Although not scheduled for a deployment to the western Pacific, Segundo departed San Diego within a week after being notified of her special assignment and got underway on 27 November 1956, for her sixth deployment to the western Pacific. She made port calls to Pearl Harbor; Yokosuka, Japan; Hong Kong; Subic Bay, and Manila, Philippines; and Buckner Bay, Okinawa. She returned to her homeport in San Diego on 29 May 1957.

Segundo conducted special operations in the eastern Pacific (21 October–21 November 1957, with a short rest and relaxation period for the crew in Acapulco and Ensenada, Mexico, before another regular yard overhaul at Hunter’s Point (4 January–26 May 1958).

Getting underway for her seventh western Pacific deployment on 14 August 1958, she made port calls in Hawaii; Yokosuka and Sasebo, Japan; Hong Kong; Taiwan; and Melbourne, Australia. She returned to her homeport in San Diego on 25 March 1959. Later that summer (2 July–23 July 1959, she cruised to Seattle to participate in the annual Sea-Fair Festival.

Segundo sailed for extended operations in the western Pacific, departing on 10 June 1960. She made port calls to Pearl Harbor; Yokosuka and Sasebo; Hong Kong; and Okinawa. She returned to San Diego on 14 December 1960, and underwent a regular overhaul at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, (26 January 1961–9 June 1961).

After her overhaul period ended on 9 June 1961, Segundo began months of training and short underway periods in preparation for her next deployment. Getting underway for her ninth cruise to the western Pacific on 5 April 1962, Segundo provided services for ships of the Seventh Fleet; Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force; Navy of the Republic of Korea; and the Philippine Navy. She made port calls in Newcastle, Brisbane, and Mackay, Australia; Subic Bay; Yokosuka; and Pearl Harbor. From 5–14 May 1962, she participated in the 20th anniversary commemoration of the Battle of the Coral Sea. After a very memorable and successful deployment, she returned to San Diego on 10 October.

Participating in the annual Sea-Fair Festival in Seattle (29 July–28 September 1963), Segundo also provided services to various vessels of the Pacific Fleet in Alaskan waters. While underway in the Pacific Northwest, she made port visits to Seattle; Vancouver and Victoria, British Columbia; Haines and Sitka, Alaska. On 4 December, she sailed to Mare Island Naval Shipyard to undergo a regular overhaul, coming out of the yards on 7 April 1964. Segundo began sea trials in the Pacific Northwest (22 April–29 May 1964), making port calls in Bangor, Wash., and Vancouver, British Columbia.

Deploying on her tenth western Pacific operation on 4 August 1964, Segundo sailed first to Pearl Harbor. Other ports visited included Yokosuka, Sasebo, and Iwakuni, Japan; Hong Kong; Subic Bay. Segundo’s sailors were awarded the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal for this deployment, which ended on 19 February 1965.

Segundo participated in the annual Midshipman Cruise (19 June–7 July 1965), visiting Port Angeles, Wash. Later that month, on 19 July, she received the 1965 fiscal year Battle “E” Efficiency Award for SubDiv 31. From 6 September – 21 October, Segundo conducted interim docking and main storage battery renewal at the Hunter’s Point Division of the San Francisco Bay Naval Shipyard.

Steaming ahead to support allied forces in Vietnam (18 March–24 September 1966), Segundo participated in operations with naval and air forces of the U.S, U.K., Australia, New Zealand, Republic of China, Philippine Republic. She also provided underway training for the Royal Thai Marines of Thailand. Ports visited on this deployment included Pearl Harbor; Yokosuka; Buckner Bay; Keelung/Taipei, Taiwan; Subic Bay and Manila; Hong Kong; Bangkok, Thailand.

Conducting workups in the Northern Pacific and Puget Sound areas (9 May–21 June 1967), Segundo participated in a reserve training cruise and underwent a full weapons system/fire control evaluation. Segundo provided services to various Canadian and U.S. forces while deployed in the area. From 9–11 June, she participated in Portland’s annual Rose Festival, Ore. Her sailors enjoyed liberty in the cities of Vancouver and Nanaimo, B.C.; and Bangor, Wash. From 7–13 July, Segundo participated in Dynamic Action, a major First Fleet exercise, before she returned to San Diego for minor repairs and leave before her next deployment.

Segundo proceeded to the western Pacific on 18 August 1967. She made her usual liberty calls in Pearl Harbor; Yokosuka and Sasebo; and also in Hong Kong. She sailed back for home and returned there on 20 February 1968.

A board of inspection and survey finding Segundo unfit for further service in July 1970, she was decommissioned on 1 August 1970 and stricken from the Naval Register a week later, on 8 August 1970. She was sunk as a target by Salmon (SS-573) on 8 August 1970.

Segundo received four battle stars for her World War II service and one for the Korean War.

| Commanding Officer | Date Assumed Command |

| Lt. Cmdr. James D. Fulp Jr. | 9 May 1944 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Stephen L. Johnson | 29 June 1945 |

| Cmdr. Morton H. Lytle | 10 February 1946 |

| Lt. Cmdr. George S. Simmons II | 15 July 1948 |

| Lt. Cmdr. John H. Bowell | c. 1 June 1950 |

| Cmdr. Ralph G. Johns Jr. | 5 August 1952 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Harold S. Howard | 25 July 1953 |

| Lt. Cmdr. James C. Gibson | 5 June 1954 |

| Lt. Cmdr. William C. Amick Jr. | 20 September 1955 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Robert G. Douglas | c. 10 October 1957 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Robert A. Aiken | 12 May 1959 |

| Lt. Cmdr. John K. McGoneghy | 20 May 1961 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Rex E. Maire | c. 10 July 1963 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Robert L. Chasse | c. 25 May 1965 |

| Lt. Cmdr. David A. Fudge | 5 April 1967 |

| Cmdr. Anthony C. Cajka | 1 April 1969 |

Guy J. Nasuti

1 March 2018