Cook II (DE-1083)

1971–1995

The second U.S. Navy ship named Cook and the first named for Wilmer P. Cook. Cook was born in Annapolis, Md., on 1 October 1932 and received an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1952 following a year at the University of Maryland in College Park, Md. Although his father was employed at the academy, Cook was not immediately accepted into it upon his application. As his brother, John Cook, recalled in an interview conducted on 25 November 1989, “[Wilmer] was a third alternate for acceptance and he knocked on all kinds of doors to get in…. He really wanted to be career Navy.” Following his commissioning as an ensign on 1 June 1956, Cook reported for flight training at Naval Air Basic Training Command, Pensacola, Fla., and Naval Air Advanced Training in Memphis, Tenn. He was designated as a naval aviator on 18 October 1957.

Upon completion of that period of instruction, Cook returned to the Naval Air Basic Training Command, remaining there until January 1958. He subsequently attended Weapons Systems School at the Naval Air Technical Training Center in Jacksonville, Fla. before joining Attack Squadron (VA) 125 in June 1958 as a Douglas A-4D Skyhawk pilot. He later served as a fleet pilot and weapons officer with VA-216 (February-July 1959) before transferring to VA-192. He also qualified as officer of the deck while in the attack aircraft carrier Bon Homme Richard (CVA-31). Eventually, he transferred to VA-112 to serve as assistant operations officer and material officer.

Cook next served as an aviation science instructor and foreign student liaison officer at the U.S. Naval School, Pre-Flight, Naval Air Station (NAS) Pensacola (1962-65). He subsequently joined VA-125 as a fleet pilot. Owing to his considerable skill and experience with the Skyhawk, he trained fleet replacement pilots and enlisted men in the operation of the A-4. On 1 August, he received a promotion to lieutenant commander. Shortly thereafter, in November 1965, Cook transferred to VA-155, in Carrier Air Wing (CVW) 15.

As a member of VA-155, Cook served Vietnam tours, flying over 300 missions in an A-4E. Starting in November 1965, he and his squadron were embarked in Constellation (CVA-64). Arriving off the coast of Vietnam on 15 June 1966, Constellation and CVW-15 were assigned to the Seventh Fleet and tasked with conducting operations against the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) and other military targets in North Vietnam. On 6 August 1966, Cook led a section of aircraft on a search and destroy mission against enemy torpedo (PT) boats south of Hon Gay Naval Base in North Vietnam. Discovering a heavily-camouflaged Swatow-class PT boat, Cook delivered two 1,000-pound bombs, one of which struck the aft section of the craft and sank it. He and his section subsequently encountered another PT boat that they significantly damaged but did not destroy. For these actions, Cook would posthumously receive his first of seven air medals (Bronze Star in Lieu of the First Award).

Cook earned his first Distinguished Flying Cross just six days later when he led a flight of four A-4Es on a surface-to-air missile (SAM)-suppression mission during an attack on the Thuong Thon petroleum, oil, and lubricant storage area southwest of Hanoi. Escorting an attacking force of fourteen strike aircraft, Cook courageously exposed himself to enemy missile fire in order to deliver a point-blank attack against one of the firing sites, disabling its guidance system. He continued to harass other missile sites until the strike force had made a successful egress. Such bold behavior in the face of enemy fire was a hallmark of Cook’s flying career. “He could do things no one else could do,” his brother recalled in a 1989 interview, “but he said he couldn’t teach others what he knew.”

Later that month on 31 August 1966, Cook led a night-time mission to investigate a high-speed surface contact a few miles east of the port of Haiphong. With only flare illumination to guide them, Cook and his section came under heavy fire from an enemy patrol craft. Unable to leave the illumination cone due to the 1,500-foot overcast, he and his section made their bomb and rocket runs at minimum altitude and within range of the enemy’s guns. Nonetheless, their attacks sufficiently damaged the enemy vessel to set it aflame, forcing its crew to beach it. The accomplished naval aviator and his squadron subsequently destroyed the patrol craft, earning him a posthumous Navy Commendation Medal for “outstanding airmanship and aggressive determination in the face of adverse weather conditions, and while under enemy fire.”

On 21 September 1966, Cook successfully led another SAM-suppression mission in support of an air strike on the railroad, storage, and transshipment complex of Thanh Hoa. Once again, he exposed himself to heavy ground fire in order to protect the strike group, harassing the enemy and evading their attacks for over thirty minutes until the strike force had completed its mission and left the target area. Cook would posthumously be awarded his second Air Medal (Gold Star in Lieu of the Second Award) for his actions and “sound leadership.”

Cook’s leadership skills earned him two more Navy Commendation Medals over the course of two days in October 1966. On 21 October 1966, he led a SAM-suppression mission against the Quang Suoi petroleum storage area and transshipment depot, after which his flight reconnoitered the area south of the target site. Observing multiple ocean-type barges unloading at the mouth of the Thanh Hoa River, Cook unleashed a Bullpup (AGM-12) air-to-ground missile attack against the barges. Assessing the damage, Cook quickly recognized that the barges were carrying ammunition, and attacked once more. He then called in three additional strikes, completely destroying the barges. All of this was accomplished while in the teeth of heavy antiaircraft fire.

Less than a day later, Cook led another mission consisting of two strike craft and two SAM-suppression bombers against the Mai Xa railroad and highway bridge. After successfully destroying the target, Cook rendered assistance to a fighter plane which had been downed during the assault. Directing the rescue helicopter to the scene, Cook led his flight in strafing attacks against multiple North Vietnamese fishing junks attempting to capture the downed pilot, enabling him to be retrieved.

Cook undertook another SAM-suppression mission on 6 November 1966. Leading a flight of two A-4Es, Cook and his wingman were charged with protecting two photo-reconnaissance planes as they flew over the Hai Duong Bridge. Drawing away the radio-controlled antiaircraft fire and missiles from the reconnaissance flights. Cook and his wingman pressed the attack on the enemy launching sites, destroying two of them in the process. All of this was achieved under heavy fire, with one missile even coming within 500 feet of Cook’s aircraft.

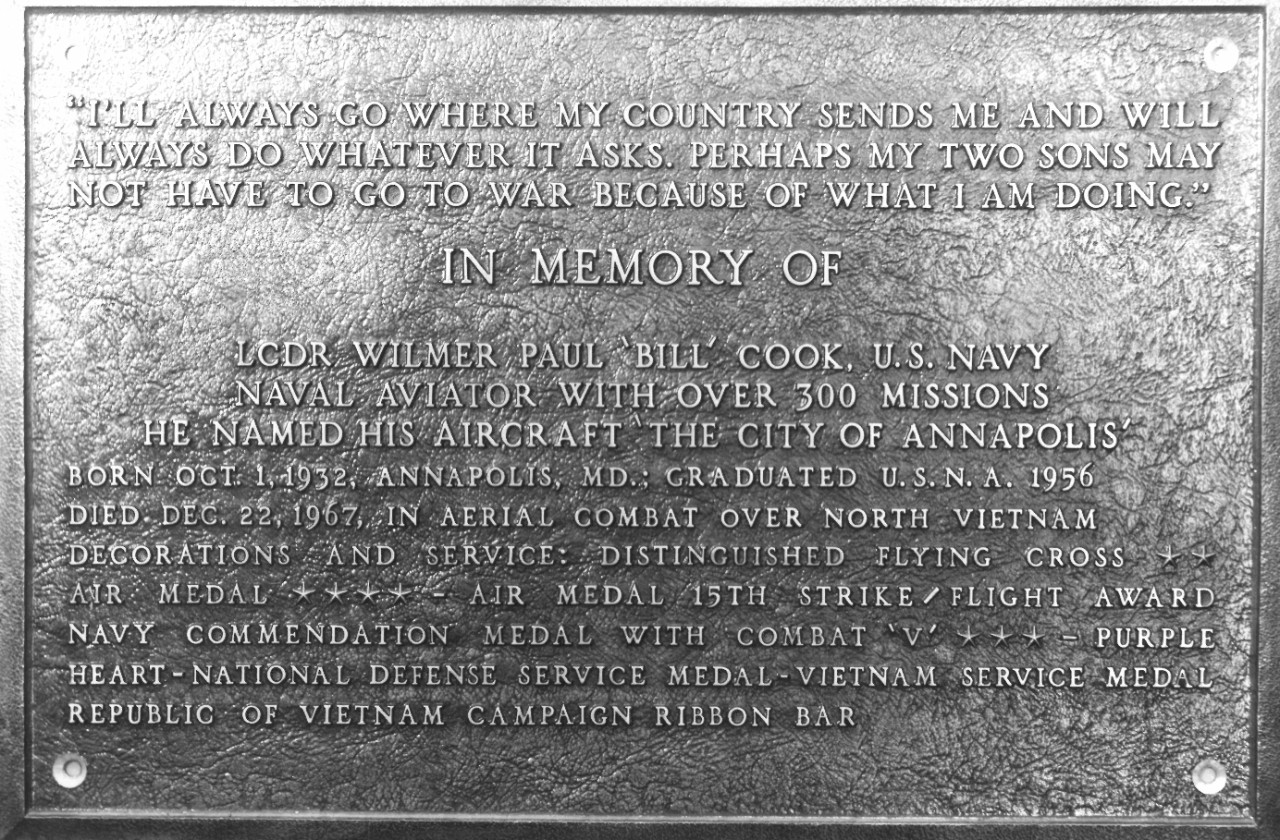

Cook’s first Vietnam tour ended with Constellation’s return to San Diego on 3 December 1966. Although he could have requested shore duty to train others to fly the A-4E, Cook volunteered for a second Vietnam tour in 1967. Prior to his departure, he flew back to Annapolis in May 1967 to see his parents. As his father later recalled in a letter on 18 October 1968 to Rear Adm. Ernest M. Eller, the Director of Naval History, when asked why he wanted to go back, Lt. Cmdr. Cook replied, “I’ll always go where my country sends me and will always do whatever it asks. Perhaps what I am doing may keep my two sons from going to war.”

On 20 June 1967, CVW-15 embarked in Coral Sea (CVA-43). Much as he had done during his earlier service in Constellation, Cook distinguished himself during numerous SAM-suppression missions and attacks on PT boats. On 17 September 1967, he participated in an air strike on a railroad/highway bridge in Haiphong, drawing fire from two separate missile sites for nearly 30 minutes while the attacking force complete its mission. He participated in another strike in the same area just a day later, evading two surface-to-air missiles as he executed a perfect dive-bombing run on the bridge approaches. For his actions on both days, he would posthumously receive his fourth and final Navy Commendation Medal (Gold Star in Lieu of the Fourth Medal) and fifth Air Medal (Gold Star in Lieu of the Fifth Award).

Cook achieved another significant milestone on 21 October 1967. While conducting an early morning coastal reconnaissance patrol amidst threatening overcast and reduced visibility, he and his squadron detected six PT boats. Upon sighting the aircraft, the boats raced out from under cover and opened fire, forcing Cook and his wingmen to undertake evasive maneuvers at low altitude. Determined to gain a favorable firing position on the enemy, Cook entered the overcast and made a shallow diving turn, relying solely on his instruments and own sense of timing. With the enemy now back in his sights, he released a bomb right into the center of their formation, sinking four of them and significantly damaging the other two. Having previously sunk one PT boat, Cook earned himself the distinction of being Coral Sea’s first “PT-boat ace.” He would also be awarded his third Distinguished Flying Cross posthumously.

Cook flew more missions following that, earning himself two more air medals in the process. Following the death of the squadron’s commanding officer, Cmdr. William H. Searfus, Cook became acting CO of VA-155. As his roommate later recounted, when asked if the squadron could handle its duties without its senior officers, Cook replied, “If you can turn this boat [sic] into the wind, you will see Attack Squadron 155 ready to launch aircraft and hit our assigned targets.”

On 22 December 1967, Cook and two other members of VA-155 were ordered to destroy a pontoon bridge on a supply route between Vinh and Ha Tinh. As they approached the target, they encountered heavy cloud cover, forcing Cook to drop below 2,500 feet to locate the target. The precise details of what occurred at this point are unknown, but when he came back up, his two wingmen reported that his plane was on fire. While no one had seen firsthand what had occurred below the overcast, it is quite likely that the pilot had been struck by either small arms fire or fragments from his own bomb. He tried to reach the coast, but at some point along the way, he ejected from the aircraft. A rescue helicopter was sent to retrieve him, but as it drew within two to three feet of his prone form, it appeared that Cook had suffered a broken neck and significant trauma to the back of his head, either as a result of the ejection or enemy gunfire. Believing him to be dead and drawing intense fire from nearby North Vietnamese soldiers, the pilots ultimately withdrew before they could land and retrieve his body. “Had there been any hope of life, he would have been picked up,” Cmdr. James B. Linder of CVW-15 wrote mournfully to Cook’s widow, Joan. He went to on to emphasize that, “I wish to God we could bring him back but we can’t.”

Although the rescue team was certain that Cook was deceased, among Cook’s surviving family members, questions still lingered about whether he might have survived and been taken prisoner. They would wait nearly twenty years to receive a definitive answer. In the interim, the Navy memorialized Cook by naming escort ship DE-1083 in his honor. At the ship’s launching ceremony on 23 January 1971, with Cook’s family in attendance, Vice Adm. Thomas F. Connolly, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (Air), spoke eloquently of Cook’s accomplishments and read aloud remembrances from some of his shipmates. One of them described their fallen comrade thusly:

The human side of “Cookie” [Cook] is somewhat at odds with our movie version stereotype image of a heroic pilot should be. In appearance, he certainly cut no dashing figure; he was a round, balding man with a black mustache perched on top of his ever-present smile. He didn’t talk like John Wayne - rather his sentences were long, the logic sometimes involved, and he wasn’t afraid to use words of greater than one syllable. He wasn’t grim and determined - he always seemed to inject humor and appeared to be taking things lightly.

However, Bill did fulfill some aspects of the stereotyped hero. He greatly enjoyed life. He liked people, conversation and argument - and he was dedicated to his country, his home, and the Navy. I thought the world of “Cookie” - he was one hell of a man.

On 15 December 1988, Vietnam returned the remains of four men as part of a repatriation agreement with the U.S. government. For nine months, forensic specialists at the Army Identification Lab at Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii worked to identify the fallen. Eventually, Cook’s remains were positively identified alongside those of USAF Col. Jerdy A. Wright Jr., Lt. Col. Robert E. Bush, and Maj. Charles J. Huneycutt, Jr. On 30 September 1989 all four were transported with full military honors from Hickam to Travis Air Force Base in California.

At the request of Cook’s sons, a memorial for their father was held on board frigate Cook on 24 November 1989. As Cmdr. Richard W. Kalb, the ship’s CO, noted solemnly, “It's a rare occasion for a ship and her crew to be able to honor the man for whom the ship is named and to commend the remains to the deep.” For Cook’s sons, the occasion proved even more emotional, with his youngest son, John, noting, “This will be the first time I’ve been in my father’s presence for 22 years.” He went on to state, “I don’t know how to react because it’s like a new thing, like becoming aware that my father is really here.”

Cook’s ashes were scattered from Cook’s deck into the Pacific on 27 November 1989, bringing to an end a nearly twenty-year ordeal for his family and finally laying the accomplished naval aviator to rest. For his valiant efforts, he received the Distinguished Flying Cross (Four Stars), the Air Medal 15th Strike/Flight Award, , Navy Commendation Medal with Combat “V” (Three Stars), , the Purple Heart, the National Defense Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal, and Republic of Vietnam Ribbon Bar.

II

(DE-1083: displacement 4,200; length 438'0"; beam 46'9"; draft 24'9"; speed 27 knots; complement 242; armament 1 5-inch, 1 ASROC, 6 MK32 torpedo tubes, 1 helicopter, class Knox)

The second Cook (DE-1083) was laid down on 20 March 1970 at Westwego, La., by Avondale Shipyards, Inc.; launched on 23 January 1971; sponsored by Mrs. Joan C. Nelson, widow of the late Lt. Cmdr. Wilmer P. Cook; and commissioned on 18 December 1971 at Boston [Mass.] Naval Shipyard, Cmdr. James R. Talbot, Jr., in command.

The thirteenth in a series of 26 newly designed destroyer escorts, Cook was specially designed for anti-submarine warfare, being equipped with an ASROC launcher, a Light Airborne Multi-Purpose System (LAMPS), and sonar (AN/SQS-26 CX, AN/SQS-35 IVDS, AN/SQR 18 Tactical Towed-Array Sonar System [TACTASS]). In addition, she was the first ship to utilize the Fleet Introduction Team (FIT) concept, a process intended to enhance a crew’s familiarity with their new vessel while, at the same time, reducing the number of individuals and days required for pre-commissioning detail. Cmdr. Talbot, a descendant of Commodore Silas Talbot (second commanding officer of frigate Constitution), was tasked with overseeing this process in order to lay the groundwork for its implementation in the fitting out of all future naval vessels.

Cook’s shakedown cruise began in Boston, Mass., on 24 February 1972. In honor of its namesake, Cook’s first port-of-call was Lt. Cmdr. Cook’s hometown of Annapolis on 25 February. From there, the operational plan was to sail down the Atlantic conducting goodwill visits at ports along the way, transit through the Strait of Magellan, and join Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 3 of the Pacific Fleet at Long Beach, Calif. After stopping in Yorktown, Va., and Norfolk, Va., from 26 February to 1 March to carry out her first ammunition and provision loadouts, respectively, Cook sailed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba to conduct selective shakedown training exercises. Arriving on 3 March, Cook and her crew underwent a Training Readiness Evaluation Inspection and a walkthrough of other drills they would be undertaking.

Upon completion of training, Cook sailed for Montego Bay, Jamaica, on 10 March 1972, followed by a brief journey to Curacao, Netherlands Antilles, on 13 March. Partway through the latter leg of this voyage, on the morning of 14 March, Cook’s bridge watch caught sight of smoke on the horizon. At the same time, the ship received a distress signal from the Barao de Maua, a 5,000-ton Brazilian cargo ship out of Rio de Janeiro that had suffered a fire at sea off the coast of Aruba due to an explosion in the cargo hold. A 16,000-ton Swedish container ship, Antonia Johnson, was already on the scene as was a U.S. Coast Guard sea plane. Receiving a request for medical assistance from Antonia Johnson, Cook dispatched HMC Jerry van Tasswell to the ship. Casualties among Barao de Maua’s crew numbered six dead from the initial explosion, two while abandoning ship, four with significant burns, twenty-six with cuts and bruises, and one missing. While HMC Tasswell rendered assistance, Cook circled the Barao de Maua until 1530 in an unsuccessful search for the missing sailor.

Cook arrived at the port of Willemstad in Curaçao on 15 March 1972 and departed two days later for Recife, Brazil. Prior to her arrival, however, the ship’s company had to undergo a hallowed rite of passage: the “crossing-the-line” ceremony. Conducted whenever a ship crosses the equator, those sailors who have not yet journeyed between hemispheres (referred to as “pollywogs” or, more derisively, “slimy wogs”) during a sea voyage undergo a series of secret initiation rites known only to those who have previously been indoctrinated into the mysteries of the Deep (the so-called “faithful [and, occasionally, crusty] shellbacks.”). In a letter to the friends and family of Cook’s crew, Cmdr. Talbot described the ceremony that took place on 22 March 1972 thusly: “Today we initiated 195 lowly, crawling Pollywogs into the exalted society of Shellbacks. Davey Jones came aboard [sic] over the bow last night and asked us to prepare. We did, and today he escorted Neptunus Rex, with his whole court, aboard for the initiation.” He went on to note rather archly that even a few days later, “Most are still ragged around the edges from the ordeal of initiation.”

Cook arrived in Recife, Brazil on 24 March 1972 for a routine refueling stop. Shortly thereafter, on 27 March, she anchored in Rio de Janeiro’s harbor and received visits from a number of U.S. and Brazilian dignitaries and military officers. In recognition of Cook’s role in assisting Barao de Maua’s crew, Vice Adm. Vivaldo Cheola, technical director and Commodore of Lloyd Brasilliero (Brazil’s state shipping company), presented Cmdr. Talbot with an engraved silver plaque expressing Lloyd Brasilliero’s gratitude.

Departing Rio de Janeiro on 30 March 1972, Cook made her way down the Rio de la Plata, arriving at Buenos Aires at 1230 on 1 April. Over the course of two days, hundreds of people toured the ship including U.S. Ambassador to Argentina John Lodge. Cook began her transit of the Strait of Magellan and the Smyth Passage on 3 April. She attempted to refuel at the city of Punta Arenas, but was unable to make a safe approach to the offshore mooring buoy due to high winds. Sailing on, Cook completed her transit of the strait and finally reached the Pacific Ocean on 9 April at 1200. She moored at the naval base in Valparaiso, Chile (11-14 April) before proceeding to Callao, Peru, for refueling. On 17 April, Cook rendezvoused with her sister ship Stein (DE-1065), which was also on her shakedown cruise. The crews of both ships conducted formation exercises for over a day before continuing onwards to the next leg of their respective voyages. Cook reported to the Pacific Fleet on 21 April and arrived in Acapulco, Mexico, on 23 April for two days of liberty followed by an all-hands effort to prepare the ship for her arrival at her home port. She then sailed onward from Acapulco on 25 April and, after a brief fueling stop in Manzanillo, Mexico the follow day, finally arrived in Long Beach, Calif. On 29 April at 1100.

Cook’s arrival in California was highly anticipated. In response to the internal political turmoil caused by the Vietnam War, the city of Cypress, Calif., offered to “adopt” the Cook to demonstrate its support for the armed forces. On 20 May 1972, during the Cypress Spring Festival, Cook was officially adopted by the city and made an honorary member of the local Chamber of Commerce. In the week following the festival, Cook undertook her final contract trials. She then cruised to Portland, Ore., on 5 June for the Rose Festival. Before Cook and her crew could partake in these festivities, however, they had to undertake the solemn duty of committing the remains of USN FTC (Ret.) Sven Wilhelm Carlson, Jr., and USMC 1st Lt. (Ret.) Harry Gordon Brown to the deep.

On 6 June 1972, Cook rendezvoused with guided missile frigate Fox (DLG-33) and oiler Cacapon (AO-52). After conducting underway replenishment (UNREP) exercises, she and the rest of the task group (including Stein) sailed for Astoria and from there, made their way upriver in formation on 8 June. Arriving in Portland, Cook spent the next three days moored in the city harbor along with 17 other ships. An estimated 4,486 visitors toured the ship while another 175 sailed on board Cook from Portland to Astoria on 12 June. She returned to Long Beach two days later.

Cook commenced her post-shakedown availability at the Long Beach Naval Shipyard on 26 June 1972. In addition to receiving minor repairs, Cook’s Basic Point Defense Missile System (BPDMS) and major ASROC system were installed. The ship’s fuel system was also modified to burn clean Navy Distillate fuel, as was its structure to accommodate the LAMPS manned combat helicopter that would be embarked during her deployments. All of this took nearly four and a half months.

During her stay in the shipyard (27 July-15 August 1972), Cook served as a host ship for the Japanese guided missile destroyer Amatsukaze (DDG.163), which was visiting the U.S. for training and technical assistance under the Military Aid Program. Cook’s crew also stood ready to render assistance when a small fire broke out on board the destroyer Agerholm (DD-826) on 17 August. Between 13 and 15 October, she once again served as a host ship for a Japanese vessel, this time Mochizuki (DD.166).

Cook finally completed her post-shakedown availability on 10 November 1972. Over the next month she underwent a series of tests, including firing her ASROC for the first time and launching her first Point Defense (RIM-7 Sea Sparrow) missile. She then performed plane guard duty for Coral Sea on 9 December, a task that proved more eventful than expected, as a McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II attempting to land on the carrier went into the sea at 1825 on 10 December. A helicopter from the carrier retrieved the pilot while Cook rescued a radar intercept officer. Later that night, Cook was detached from her assignment and moored in Long Beach completing her first full year of active service. A ceremony held on 18 December celebrated Cook’s first anniversary.

The first four months of 1973 saw Cook undertaking intensive preparations for her first deployment. Fittingly, Cook’s commanding officer during this deployment, Cmdr. Carl A. Nelson, had been a Naval Academy classmate of the man for whom the ship was named. On 7 May, Detachment (Det.) Three of Light Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron (HSL) 31 embarked on board Cook, providing the vessel with its Kaman SH-2D Seasprite LAMPS helicopter for the duration of the deployment.

With all preparations having been made, Cook deployed for the first time on 9 May 1973 as part of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 9. Departing Long Beach, Cook sailed with guided missile destroyer John Paul Jones (DDG-32), Edson (DD-946), and Francis Hammond (DE-1067) to Pearl Harbor, Hi. While en route, Cook and Francis Hammond conducted convergence zone (CZ) sonar operations on 13 and 14 May. A day later, Cook arrived at Pearl Harbor to receive her first deperming. After a brief stop at Barking Sands to conduct gunnery and missile exercises, the ships sailed for the Philippines. While en route, Cook and Francis Hammond stopped to refuel at Midway Island on 21 May along with the rest of the squadron before detaching once more to conduct CZ sonar operations over the next two days. On 24 May, both ships detached from their squadron and proceeded to Guam, Marianas Islands. Reaching the island on 28 May, Cook and Francis Hammond stopped to refuel and departed on the same day.

Cook and Francis Hammond finally arrived in Subic Bay, Republic of the Philippines on 1 June 1973. On 8 June, Cook escorted Constellation from Yankee Station to Subic Bay. After successfully completing this mission on 13 June, Cook departed for Singapore, Malaysia. Before the ship could even leave the harbor, however, she was recalled and reassigned to Task Force 78 to assist with the second phase of Operation End Sweep, a minesweeping operation to remove or destroy mines along the North Vietnam coast following the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in January 1973. Departing on 16 June with amphibious transport docks Ogden (LPD-5) and Duluth (LPD-6) for the waters near Haiphong, North Vietnam, Cook’s mission was to provide an anti-air picket to protect the minesweeping vessels operating in the area. After being relieved on 27 June, Cook escorted the special minesweeper (modified tank landing ship) Washtenaw County (MSS-2) to Subic Bay. Cook was then detached from Task Force 78 to assume escort duties for Constellation once more.

On 15 July 1973, Cook got underway for Yokosuka, Japan. After being briefly recalled to TF 78 and a refueling stop at Kaohsiung Harbor, Taiwan, Cook arrived at Yokosuka on 24 July to participate in a U.S. – Japanese midshipman exchange cruise. Over the course of three days, Cook, Parsons (DDG-33), and Gurke (DD-783) participated in combined exercises with five units of the Japanese Maritime Defense Force. At the conclusion of the exercises on Sasebo, Japan on 1 August, Cook sailed to Chinhae (Changwon), Korea, to conduct a joint anti-submarine warfare (ASW) exercise with the Republic of Korea Navy (7-12 August).

Upon completion of those evolutions, Cook, cruised to Keelung, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. From 12 September until 24 September 1973, Cook assumed escort duties at an anti-air warfare (AAW) picket station in the Gulf of Tonkin. While returning to Subic Bay, Cook received a distress signal from Military Sealift Command (MSC) cargo ship USNS Sergeant Jack J. Pendleton (T-AK-276), which had run aground off the coast of Triton Island in the Paracel Chain. Cook reversed course and arrived at the island at 1400. England (DLG-22) was already on the scene, but departed once it became clear that no immediate danger existed. Cook remained in visual signaling range until the arrival of salvage tug Beaufort (ATS-2) on 27 September.

After returning to Subic Bay, Cook commenced her voyage back to Long Beach on 8 October 1973. Instead of immediately transiting across the Pacific, however, Cook first went south for a goodwill tour of Australia, visiting Darwin, Freemantle, Perth, Albany, and Brisbane (12 October-4 November). She then rendezvoused with Francis Hammond to make a joint call at Auckland, New Zealand. Following the conclusion of this tour on 12 November, both ships sailed across the Pacific and arrived back in Long Beach on 28 November.

Having completed her first tour, Cook and her crew spent much of 1974 engaged in ship maintenance and training operations along the west coast. While serving in Task Unit (TU) 37.3.1 along with Hancock (CVA-19), Cook conducted a burial-at-sea on 3 March for two retired navy men, Lt. Cmdr. Donald J. Bunker and Louis J. Strepka. After Barbey (DD-1088) relieved her, Cook was attached to TU 37.6.1 to serve as a rescue destroyer and a plane guard for Constellation on 11 March. Francis Hammond relieved her four days later.

On 25 June 1974, Cook travelled to Everett and Seattle, Wash., in the company of guided missile cruiser Long Beach (CGN-9) for port visits. While in Everett, Cook’s crew participated in community events, providing an honor guard for the July 4th parade. The ensuing months were largely taken up with training drills and fleet exercises. Cook also had the honor of hosting a change of command ceremony for DesRon 9 on 5 September, with Capt. Frank C. Collins, Jr., relieving Capt. Gerald E. Thomas. On the same occasion, Rear Adm. Mark W. Woods, Commander Cruiser-Destroyer Force, Pacific Fleet, promoted Thomas to the rank of rear admiral. At the time, Thomas was just the second African-American to attain this rank.

Cook departed for her second western Pacific (WestPac) tour on 5 December 1974 in the company with Edson (DD-946). They rendezvoused with Coral Sea en route to Pearl Harbor, and from there, proceeded to the Philippines, stopping only briefly to refuel from Ashtabula (AO-51) on 16 December before arriving in Subic Bay on 29 December. She remained drydocked there until 21 January 1975, when she departed for the South China Sea as an escort for Coral Sea and to participate in missile exercises. Cook later participated in ASW evolutions with the Japanese Maritime Defense Force at Yokosuka, Japan (20-24 February), and once again served escort duty for Coral Sea until mid-March, when she returned to Subic Bay for routine upkeep.

At the same time as this was occurring, the political and military situation in the Republic of Vietnam was rapidly deteriorating. With the North Vietnamese making their final push to capture Saigon, the Navy had been tasked with assisting in the evacuation of tens of thousands of U.S. and South Vietnamese political and military officials. On 6 April, Cook escorted Hancock through the South China Sea and the transit to Singapore alongside her sister-ship Kirk (FF-1087). Their layover in Singapore was abruptly cut short when it became clear that Saigon’s fall was imminent and that TF 76 would need to get underway immediately to assist with the evacuation effort, designated Operation Frequent Wind. The ships arrived 12 miles off Vung Tau on 20 April.

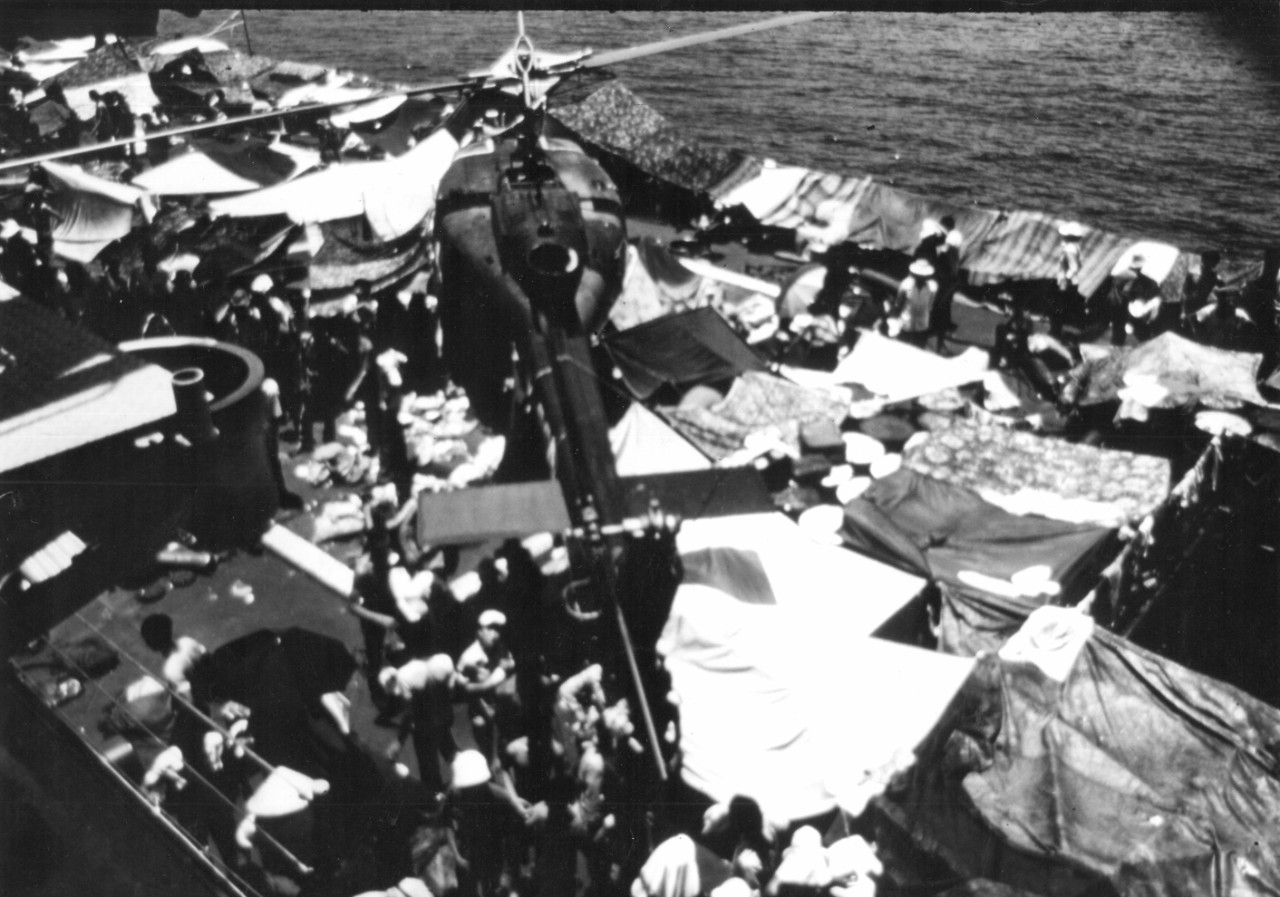

Upon arrival, Cook’s crew beheld a sea filled with numerous small boats and sky filled with helicopters, all carrying refugees. Lt. Cmdr. Raymond W. Addicott, Cook’s executive officer, later recounted to historian Jan K. Herman that the image on the radar scope “looked a swarm of bees.” He went on to recount, “I went topside on the bridge and the sky was just full of helicopters. It was an amazing sight.” Some of them were Marine and Air Force helicopters evacuating people from Saigon, but there were also hundreds of Vietnam Air Force (VNAF) Bell UH-1 Iroquois helicopters (better-known as “Hueys”) flown by south Vietnamese pilots who had fled with their friends, neighbors, and relatives in tow. Midway (CVA-41) and Hancock along with the amphibious command ship Blue Ridge (LCC-19), attracted the initial wave, but eventually, smaller ships such as Cook and Kirk had to take on refugees. Given her smaller size and the LAMPS that was already on board, Cook could not easily accommodate the additional aircraft on her flight deck. The solution to this problem was to push the helicopters into the sea after disembarking all passengers, but Cook’s non-skid deck complicated the issue. Resourceful boatswain’s mates, however, got around this problem by rocking the helicopters onto a three-inch steel pipe and then rolling it off the deck.

Safely landing helicopters proved to be not the only challenge confronting Cook’s crew. The hundreds of small boats in the water, many filled well beyond their capacity, left people exposed to the elements amidst extremely unsanitary conditions with precious little to food, water, or medical supplies. The doctors and corpsmen on Cook and other ships worked feverishly to treat the influx of evacuees, with her LAMPS helo even transporting one severely injured evacuee from Kirk to the ammunition ship Flint (AE-32). In addition to treating the injured, the ill, and the malnourished, Cook’s medical people also attended to a number of pregnant women. Despite the crew’s “great hopes” that at least one of the women would give birth on board the ship (perhaps in the hope that they would name the child after the ship), Cmdr. McMurry reported that no babies were born on board Cook.

In addition to the humanitarian efforts off the coast of Vung Tau, Cook also undertook an important strategic operation. Although South Vietnamese ground forces had been defeated, thirty naval ships remained intact and moored of the coast of Con Son Island along with two fishing trawlers and an estimated fifty other vessels (not counting numerous small fishing boats). In order to prevent the ships from falling into North Vietnamese hands and to preserve the lives of those on board, Cook rendezvoused with Kirk and the Southern Vietnamese fleet to form a five-mile-long convoy that would safely lead the ships to Subic Bay. They were joined by Denver (LPD-9), tank landing ships Barbour County (LST-1195) and Tuscaloosa (LST-1187), salvage ship Deliver (ARS-23), amphibious cargo ship Mobile (LKA-115), stores ship Vega (AF-59), fleet tugs Abnaki (ATF-96) and Lipan (AT-85), and Flint. Although Cook and Kirk could only proceed as fast as the slowest ship (about 5 knots), they safely escorted the flotilla to Subic Bay on 7 May 1975, saving an estimated 30,000 evacuees.

Cook conducted further surveillance operations to locate refugee ships from 19-21 May 1975 before undertaking escort duty for Hancock. Following the end of her escort duty and upkeep on 5 June, Cook sailed for San Diego from Subic Bay in company with Flint, arriving on 23 June. Shortly thereafter, she was reclassified as a frigate (FF-1083) on 30 June 1975 as part of the Navy-wide reclassification of cruisers, frigates, and escort ships. The ensuing months were considerably calmer than the tumult that preceded them, as Cook and her crew predominantly engaged in fleet exercises along the Pacific Coast, including an operation in Mazatlan, Mexico, in the company with Francis Hammond (29 August-5 September).

After a prolonged period of industrial availability and drydocking to replace her propeller at the beginning of 1976, Cook got underway for her third WestPac deployment on 13 April. Arriving at Subic Bay on 15 May, she undertook a series of local operations and at-sea training until 10 June, when she accompanied Midway for training exercises in the Sea of Japan. Following a brief stop at Yokosuka, Cook sailed for Kaoshiung, Taiwan, where she engaged in ASW exercises with the Taiwanese navy beginning on 26 July. She subsequently participated in missile exercises with heavy cruiser Chicago (CG-11) and transited to Hong Kong on 3 August. Following a return to Yokosuka for a major availability, Cook conducted a 10-day patrol of Korean coastal waters in concert with Midway (21-30 August). She then made her way on 16 September to Chinhae for a joint U.S./Korean at-sea exercise, then paused for a maintenance period at Yokosuka before proceeding to San Diego (9-25 October).

After spending the remainder of 1976 on post-deployment stand down and maintenance availability, Cook got underway on 10 January 1977 for operations off southern California (SoCal), including conducting an ASW exercise with submarine Snook (SS-592) under condition 2AS. On 2 March 1977, Cook and her crew received a special visit from Vice Adm. William R. St. George, Commander of the Navy Pacific Surface Fleet, who awarded them the Meritorious Unit Commendation in recognition for their important role during Operation Frequent Wind.

The rest of 1977 would largely be consumed with training along the Pacific Coast. On 11 April, Cook got underway for MARCOT 77, a joint U.S./Canadian exercise. Prior to her arrival at Naval Station Esquimalt, Victoria, BC, Cook undertook ASW exercises with Agerholm and the submarine Gudgeon (SS-567). After a reception for the crew of the Canadian destroyer Athabaskan (DDG.282), seven Canadian ships and three Naval Reserve Destroyers conducted antiair warfare, ASW, formation steaming, and underway refueling evolutions (25-29 April). Cook subsequently made in-port visits to Vancouver, BC, and Seattle, Wash., while en route to San Diego (29 April-6 May).

During the month of June 1977, Cook engaged in multiple ASW exercises with Salmon (SS-573), as well as conducting a Mt. 51 test fire along with refueling and underway replenishment (UNREP) exercises with MSC oiler USNS Taluga (T-AO-62). Her crew also participated in a Navy training film about shipboard firefighting and, on 8 July, provided a demonstration of the new Overall Combat Systems Operability Test (OCSOT) for the Pacific Fleet ships on behalf of the Naval Sea Systems Command (NavSea). She then engaged in further ASW exercises with Snook and Gudgeon in support of CNO Project 187. The first week of August proved to be equally eventful, with Cook serving plane guard duty for Kitty Hawk (CV-63) and conducting another MT 51 test fire and UNREP with USNS Taluga.

From 23 September 1977 onwards, Cook lay berthed in Triple A Shipyard in San Francisco for a $15 million baseline overhaul with the aim of enhancing her ship fighting and ASW capabilities, as well as renewing her shipboard systems. Additions and enhancements included installing a new contaminated holding tank sewage system, a Harpoon weapons system, a number three air conditioning unit, an overhaul of the boilers and associated auxiliary machinery, a shaft rework including a new propeller, updating and augmenting electronic communications systems, and the installation of a rubber window and wide band elements (WBE) for her SQS-26 sonar. The latter is particularly noteworthy, as Cook was only the second ship in the Pacific Fleet to receive the WBE--the other being Lockwood (FF-1064).

Cook’s overhaul took nearly fourteen months to complete. During that time, she experienced nearly 75 percent crew turnover and also hosted a number of visits from foreign ships. On 28 September 1978 she received the British frigates Leander (F.109), Juno (F.52), Hermione (F.58). The next week, she hosted two Canadian destroyers Terra Nova (DDE.259) and Restigouche (DDE.257). Cook herself would attempt to get underway on 1 December, but various maintenance issues delayed the completion of her sea trials and final departure from the shipyard. On 4 December, for example, the crew discovered an unmarked blanking plate in the main engine lube oil piping system. Four days later, the fireroom flooded, with water reaching nearly eight and a half feet above the keel and causing significant damage to both boilers and their associated equipment. A recently overhauled salt-water pressure reducing valve was the cause of the problem, leaving Cook unready to sail again until 3 January 1979. Although she successfully completed most of her sea trials at this point, her crew discovered problems with the automatic boiler control (ABC). A period of intensive troubleshooting and maintenance enabled Cook to get underway finally on 18 January.

After being transferred from DesRon 13 to Desron 15 on 1 February 1979 and conducting a brief voyage to and from Mazatlan (26 February-5 March), Cook experienced further problems. In April, for example, she spent nearly a week in San Diego to fix issues with the main feed water pumps for her boilers. More significantly, Cook collided with combat stores ship Mars (AFS-1) amidst severe fog while en route to San Clement Island, Calif., on 14 May 1979. Cook’s bow was smashed in 20 feet (nearly all the way to her numbers). The damage to Mars proved even more severe, as Cook had punched an estimated 30 by 30/40 foot hole into her starboard side, about 108 feet from her bow. The hole extended below Mars’ waterline, forcing her to ballast herself in order to list on her portside to avoid flooding the starboard compartment. Despite the considerable damage they had sustained, both ships managed to limp into San Diego harbor under their own power. Fortunately, the human cost was significantly lower than the material, as only seven crew members, all from Cook, had suffered injuries. All of the injured men were part of the galley crew and had been preparing the midday meal when Cook collided with Mars. Most suffered only mild burns from spilled coffee and soup and were released from the hospital the same day, though one sailor remained hospitalized for few days with more severe burns. Perhaps on account of the relatively limited casualties, many of Cook’s veterans have joked about being the “first ship to land on Mars.”

Cook sailed for Long Beach Naval Shipyard on 1 June 1979 to spend the next month getting her hull repaired. Following a review of the accident by Rear Adm. Edward W. Carter of Cruiser-Destroyer Group 3, ComDesRon relieved Cmdr. Joseph B. Famme of his duties and temporarily placed Lt. Cmdr. Martin J. Mayer in command on 27 June. A day after he assumed command, Cook undertook her first fast cruise since the mishap.

Despite the considerable delays and maintenance caused by the collision, Cook remained on track for her WestPac deployment, undertaking numerous exercises up and down the Pacific coast including UNREP drills with fast combat support ship Sacramento (AOE-1) and USNS Taluga on 23 July and 10 October, respectively. By 11 January 1980, she was finally ready to depart for her fourth WestPac. Following an UNREP with Ashtabula on 17 January and a brief stop at Pearl Harbor a day later, Cook made for Yokosuka. During the voyage, heavy seas and high winds damaged the superstructure and the SPS-10 radar antenna pedestal, forcing Cook to undergo significant repairs upon arrival at Yokosuka on 4 February upon completion of which, Cook departed for Subic Bay, arriving on 21 February.

Cook’s fourth WestPac deployment differed significantly from her prior ones. Following a visit by Rear Adm. William C. Neel on 28 February 1980, Cook received word that she was to leave port early in order to take on Reasoner’s (FF-1063) assignments. Whereas Cook typically operated in or around the South China Sea and the Sea of Japan, Reasoner patrolled the Indian Ocean. Departing for Gonzo/Kermit Station on 4 March, Cook briefly stopped in Singapore for supplies and fuel before commencing her long voyage. On 15 March, she replaced John Paul Jones (DDG-32) in Battle Group Charlie. Sailing in company with Nimitz (CVN-68), Virginia (CGN-38), Texas (CGN-39), and William H. Standley (CG-32), Cook’s duties involved screening Coral Sea and plane guarding.

Detached from Battle Group Charlie on 4 April 1980 to replace Richard Byrd (DDG-23) on patrol duty in the Strait of Hormuz, Cook gathered information on commercial and military traffic flowing through the strait (4-10 April). Less than two weeks later, on 22 April, she conducted intelligence operations around Socotra Island in the north Arabian Sea, ostensibly, for the purposes identifying Soviet vessels sailing to and from the military base there.

Both operations and, indeed, Cook’s initial tour in the Indian Ocean and north Arabian Sea, reflected their growing strategic importance for Cold War operations. During this period, the Soviet Union had been steadily building up both her military presence and political influence within the region, partially in response to its increasing military engagement in Afghanistan and partially out of a desire to expand its sphere of influence to encompass the Arabian Peninsula. Intelligence operations such as the one Cook undertook around Socotra, were very much a response to this and the rising tensions between the U.S. and U.S.S.R at this time.

Following her mission to Socotra, Cook returned to Gonzo Station shortly thereafter for further escort duty. Battle Group Delta, led by Constellation, relieved Cook and the rest of Charlie on 1 May 1980. With DesRon 5 embarked, Cook sailed to Darwin, Australia for joint exercises with the Australian Navy. Arriving on 12 May, Cook’s crew accepted an invitation to a reception held at Coonawara navy base. They subsequently visited Cairns (19 May) and Sydney (26 May). While mooring at the latter, Cook received frigate O’Callahan (FF-1051) alongside to starboard and received an invite to Kuttabul navy base for another reception.

Such pleasantries gave way to the hard work of joint naval exercises (designated Sea Eagle) between the Australian and U.S. naval ships. Over the course of nine days (2 - 11 June), Cook, O’Callahan, Australian guided-missile destroyers Perth (D.38) and Hobart (D.39), submarine Orion (S.61) escort maintenance vessel Stalwart (D.215), and oiler Supply (AO.125) conducted ASW, AAW, replenishment at sea (RAS), and war at sea exercises. After a brief return to Sydney on 11 June, Cook set sail for Suva, Fiji to deliver materials for hurricane relief and Project Handclasp, the Navy’s humanitarian program.

On 20 June 1980, Cook departed Fiji for Pago Pago, American Samoa. Both prior to and following her stop there, she assisted in the unsuccessful search for the missing crew of the fishing vessel Hung Cheng, after which she got underway for Pearl Harbor on 23 June and from there, sailed to San Diego. Following her arrival on 12 July, Cook and her crew largely spent the next year engaged in routine drills, upkeep, and local operations around San Diego. It was not until 20 August 1981 that she finally left for her fifth WestPac deployment.

Much like her previous tour, Cook’s fifth WestPac voyage largely took place in the Indian Ocean with Battle Group Charlie. After stops in Subic Bay (21-30 September 1981) and Singapore (6-11 October), Cook transited through the Malacca Strait and into the Indian Ocean. On 20 October, she separated from the main battle group for another intelligence operation around Socotra Island. A day later, she observed a Soviet Foxtrot submarine under tow. Cook was again detached from the battle group on 16 November, this time under orders to proceed to the port Mina Salman in Manama, Bahrain. Arriving on 19 November, Cook spent nine days there before rejoining the battle group.

The next month, she received orders to proceed to within 48 hours steaming distance of Korea. She eventually sailed for Singapore, anchoring at Sambawang Naval Shipyard on 29 December 1981. The rest of Cook’s deployment largely consisted of visits to ports along the south China Sea including Subic Bay (5-9 January 1982), Sasebo (18 January-6 February), Kagoshima, Japan (11-13 February), and Pusan, S. Korea (14-17 February). Following a return to Subic Bay for four days of upkeep (1-4 March), Cook got underway for Pearl Harbor and from there, she returned to San Diego (4-23 March).

After nearly three months of maintenance, material inspections, and exercises, Cook began her ship’s restricted availability (SRA) period on 28 June 1982. The ensuing months largely consisted of local operations in the southern California area, punctuated by the occasional drills and even a dental availability in July. From 17 - 19 September, Cook again hosted Terra Nova. She also escorted battleship New Jersey (BB-62) during the month of October and assisted with Albert David’s (FF-1050) homecoming on 30 November.

By 21 March 1983, she lay ready for her sixth WestPac deployment. Cook’s deployment came at a tense time in U.S.-Soviet relations. Since coming to office, the administration of President Ronald Reagan had embarked upon a secret campaign of psychological warfare (PsyOps) against the Soviet Union. With the president’s authorization, U.S. naval ships undertook operations at the edge of Soviet waters, sometimes even deliberately penetrating them to test Soviet air and radar defenses. In some cases, they even conducted simulated air attacks on Soviet installations and planes. From April to May 1983, the Pacific Fleet conducted the large-scale naval exercises in the Pacific northwest. Forty ships, including Cook and three aircraft carriers, partook in the exercises, conducting anti-submarine operations in areas where the Soviet navy was known to have stationed many of its nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines and even staging a simulated bombing run over the island of Zelenny. At one point, the fleet even sailed within 450 miles of the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Cook did not stay for the full duration of the exercises. On 25 April 1983, she made a port visit to Chinhae, during her which, members of the crew assisted in painting a local orphanage. With this complete, Cook got underway on 30 April for Subic Bay for repair and upkeep. Two days after she arrived, Cook participated in Operation Balikatan Tangent Flash, a joint American-Philippine amphibious evolution (6-15 May). Ten days later, while en route to Singapore, she engaged in Operation Merlion with the Republic of Singapore (25-26 May).

Prior to beginning her Indian Ocean operations, Cook sailed a nearly two month-circuit between Diego Garcia, British Indian Ocean Territories, and Geraldton, Australia (1 June-20 July 1983). Her first inport visit to the former (8-19 June) primarily served as an upkeep and maintenance period with submarine tender Holland (AS-32). Geraldton, on the other hand, offered an opportunity to conduct a change of command and provide tours of the ship to celebrate Independence Day (1-8 July).

Following her second visit to Diego Garcia (17-20 July 1983), Cook commenced operations in the Indian Ocean and North Arabian Sea. Much of her time there was dedicated to conducting exercises, most notably, Operation Bright Star, a simulated amphibious assault on the coast of Somalia by multi-national forces (18-22 August). Operations concluded on 6 September when Cook pulled into Subic Bay. While there, Cook conducted community outreach, hosting a blood drive for Philippine National Red Cross and sponsoring three Filipino students for high school scholarships.

For the next month, Cook largely operated in the South China Sea, Hong Kong (21-25 September 1983), Pusan (1-4 October), and Sasebo (6-11 October). At the conclusion of these operations on 17 October, she made for San Diego, stopping briefly at Pearl Harbor on 22 October to take on stores and 35 “Tigers,” (dependents of crew members) for the final leg of the voyage. With her arrival at San Diego on 29 October, Cook had completed yet another WestPac deployment, then spent nearly a month on leave and upkeep before getting underway on 9 December to participate in exercise Kernel Usher, a simulated amphibious assault on Camp Pendleton Marine Corps Base.

With the completion of this evolution, Cook conducted an extensive ten-month overhaul (12 December 1983-6 September 1984). The crew spent the majority of the months in-between training and preparing for the various inspections that Cook would have to undergo before she was deemed ready to resume active service. Following the completion of the overhaul, Cook mainly spent the next ten months undergoing training exercises in the SoCal area for her next WestPac deployment.

Cook departed for her seventh WestPac on 24 July 1985. After spending the first few days conducting ASW exercises off the coast of Mexico, she sailed directly for Subic Bay, bypassing Pearl Harbor entirely. It was a longer than normal voyage, with Cook’s speed limited to 12 knots due to employing the so-called “sprint and drift” technique in order to tow the AN/SQS 13A array. For one sailor, this proved to be too much to bear. Already unhappy about being deployed, his mood darkened considerably when he received a letter from his wife threatening to divorce him if he did not leave the Navy. Consequently, he refused to work, earning himself punishment at the Captain’s Mast. In an attempt to get out of it, he went to Cook’s fantail and threw himself into the ocean. Fortunately, he was recovered before the sea could take him.

The rest of Cook’s transit was relatively uneventful. On 19 August 1985, she finally arrived at Subic Bay and departed four days later to conduct a 24 hour-long anti-surface warfare (ASUW) encounter exercise with the Singapore Navy. Following this, Cook transited the Malacca Strait. As she was leaving it, some of her cryptographic equipment broke down. Because Cook lacked the appropriate crypto technician on board to fix the issue, Kitty Hawk offered to have one of her technicians fix it. A Boeing-Vertol CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter was sent over with instructions to fly the equipment and the CMS custodian (a Chief Petty Officer) safely over to Fife (DD-991) for an additional pickup. However, upon lifting off from Fife, one of the helicopter’s rotors failed, causing it to crash into the deck and slip off. Luckily, Fife’s crew was able to secure the helicopter to the side of the vessel, providing Cook with the necessary time to arrive on scene and launch a motor whale boat to render assistance. Both the helicopter crew and its valuable cargo were safely recovered, none the worse for wear save for a few bruises to the Chief Petty Officer.

Operations in the Indian Ocean went considerably more smoothly. Over the course of forty days, Cook engaged in plane guarding, UNREPs, and an InchopEx with Midway’s battle group. There were also a number of ASW events, including a four day search for a Soviet Echo II class submarine (19-23 September 1985). Towards the end of September, Cook prepared to make a port call at Mombasa, Kenya and conduct a crossing-the-line ceremony, but was delayed from doing so due to a lack of preparation by the Kenyan government. Consequently, she returned to the North Arabian Sea and rendezvoused with repair ship Ajax (AR-6) off the coast of Oman for repairs. Cook finally made port in Mombasa on 9 October. Despite the initial delays, the crew enthusiastically recommended it for future port visits.

Upon leaving Mombasa on 14 October 1985, Cook proceeded to Al Masirah to rendezvous once more with Ajax. Following a change of command on 19 October, she sailed to the Gulf of Aden as part of Kitty Hawk’s battle group to conduct ASW operations (26 October-3 November). For the duration of the operations, a Soviet Udaloy-class guided missile destroyer shadowed the battle group.

Kitty Hawk’s battle group eventually split up on 9 November 1985 to visit different ports throughout the Indian Ocean. Cook steamed to Karachi, Pakistan in the company of Badger (FF-1071) and USNS Ponchatula (T-AO-148). Departing on 12 November, Cook and Badger conducted an ASW exercise with the Pakistani Navy. After Saratoga’s (CVA-60) battle group relieved Kitty Hawk’s, Cook sailed for the Philippines (27 November-1 December) and subsequently got underway for Pearl Harbor. Following a brief visit (13-14 December), she made her way to San Diego, concluding her deployment on 21 December.

Cook would not go on deployment again for another year, but she still had a role to play in the U.S.’s Cold War operations. On two separate occasions (29 January-2 February and 9-26 March 1986), she conducted AGI surveillance operations. AGI’s were Russian surveillance vessels (often disguised as fishing boats) that shadowed U.S. ships and spied upon naval operations such as weapons tests. The latter served as the impetus behind Cook’s operations. In both instances, Cook conducted “tattle-tail” operations against Primorye-class AGI’s monitoring missile tests at the Pacific Missile Test Center (PMTC). Typically, “tattle-tail” operations involve shadowing an AGI, reporting its location every couple of hours to PMTC so that it could send out Sea Knight helicopters to jam the AGI’s equipment electronically in advance of a missile launch. As Cook’s command historian described it, “Tattle-tailing involves a lot of sitting still, trying to find the best position to stay out of troughs.” He went on to note, “AGI’s do a lot of nothing, just waiting, so Cook did the same, giving out position reports all the while.” Although the author did not consider AGI duty to be particularly glamorous, nonetheless, Cook and her crew ably performed their duties, even receiving a “well done” from Rear Adm. John W. Nyquist (Commander Task Force Three Five) for their efforts. Following the second AGI operation, Cook reported to Constellation for plane guard duty during the latter’s flight ops.

On 5 May 1986, Cook entered specialized repair activity (SRA), receiving repairs to her fin stabilizers and main condenser sea valve, as well as installing a SLQ/32 EW suite, Dimension 2000 phone system, SNAP II computer system, and new tail package comprised of an AN/SQR-19A (V)1 and SQR-17A (V)2. The installations went off without issue, but the repairs proved to be considerably more troublesome. After Cook entered floating dry dock Steadfast (AFDM-14), contractors from Arcwell undertook repairs on the fin stabilizers and main condenser sea valve, as well as inspected the shaft. Upon opening the shaft, they discovered that the sleeves were pitted and scored, and that the stern tube bearing staves were worn down. The shaft was sent Long Beach shipyard, where contractors from AAA South and the shipyard crew discovered that the shaft’s coupling faces were aligned incorrectly and that water had made its way in between the shaft and its fiberglass coating.

These repairs delayed Cook’s departure for MARCOT 86. Originally, she had intended to sail to Vancouver on 4 September with Battle Group Delta and attend the World’s Fair, but Cook was not able to depart until 11 September 1986. Despite steaming at full speed, Cook was unable to rendezvous with her battle group and missed the MARCOT entirely. Proceeding to Kodiak, Ak., Cook spent three days in port (24-27 September) before leaving with her battle group to participate in FleetEx 86 involving Constellation, Ranger (CVA-61), and New Jersey Battle Groups. Following the end of this, Cook returned to San Diego, stopping in Everett, Wash. (12 - 15 October) for a public relations visit along the way.

Cook’s next assignment was to participate in ReadiEx 87-1 off the coast of southern California, as part of Kitty Hawk’s battle group on 4 November 1986. During these exercises, Cook participated in an opposed sortie, conducted a pre-action calibration firing (PACFire), and undertook sonar tracking exercises with Guitaro (SSN-665), guided missile frigate Crommelin (FFG-37), and Fox. Before the ReadiEx was complete, however, Cook suffered a crippling casualty with the dissolved oxygen content of the boiler feed water rising to a high enough level to potentially damage the boiler. Steaming back to San Diego for repairs, Cook spent a day and half inport while repair crews feverishly sought to identify and fix the problem so the ship could return to the ReadiEx. Eventually, they concluded that the issue was with the desirating feed tank (DFT) and replaced the spray valves. Cook sought to return to the ReadiEx, but eight hours into her voyage, the casualty reoccurred, leaving her dead in the water. Back at port, repair crews inspected and re-inspected the boiler plant and ran Cook through a battery of tests. Despite multiple attempts to fix the problems, the casualty continued to reoccur periodically throughout the next month, not subsiding until 5 December.

After the traditional December leave and upkeep period, Cook got underway for her MTT Phase II exercise (21-31 January 1987). As part of this, she conducted an ASW exercise with La Jolla (SSN-699). The rest of the winter months were devoted to preparations for the upcoming WestPac deployment in April. On 13 March, however, less than a month out from deploying, Cook had to drydock in Steadfast for emergency maintenance and repairs on her fin stabilizers, not undocking until 3 April. Fortunately, she was able to get underway for her deployment on schedule. With LAMPS HSL-35 Det. 3 embarked and in the company of Constellation, Cook departed ahead of Battle Group Delta to conduct flight ops. The two ships rendezvoused with the remainder of the group on 16 April while en route to Subic Bay. Cook spent much of the three week transit serving as a plane guard for Constellation.

Prior to arriving in Subic Bay, Cook suffered a casualty to her line shaft bearing causing her to go dead in the water. Working under temperatures often exceeding 100 degrees and 80-90 percent humidity, Cook’s engineers successfully replaced the bearing and got the ship underway. She arrived in Subic Bay on 3 May 1987 and undertook further repairs and maintenance.

Cook began her cruise to Diego Garcia on 8 May 1987. While transiting the Malacca Strait, Cook and Fox conducted joint exercises with the Royal Malaysian Navy including tactical maneuvers between ships, a light line transfer, flag hoist drills, and exchanging officers. On 19 May, Cook and her battle group finally reached Diego Garcia. They spent the next month conducting operations, upkeep, and exercises in and around the port.

Battle Group Delta departed Diego Garcia for the Gulf of Oman on 21 June 1987. Among her responsibilities, Cook participated in Operation Earnest Will, a U.S.-led effort to protect Kuwaiti oil tankers from Iranian attacks during the latter phase of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-8). While operating in the gulf, Cook suffered another engineering casualty on 17 August that left her dead in the water. As a consequence of the 35-40 degree rolls she experienced, Cook lost two lifeboats, only one of which was recovered. Fortunately, this was the only loss during this incident.

Cook temporarily detached from her battle group on 22 August 1987 to sail for Khor Fakkan, UAE. With the surrounding waters having been mined by the Iranians, Cook received orders to escort two U.S. merchant ships safely through these troubled waters to the port of Muscat, Oman. Proceeding slowly, Cook first escorted merchant ship President Madison through the minefield and then USNS Mediterranean (T-AOT-173). Having completed this dangerous task, Cook safely returned to Battle Group Delta that same day. Four days later, on 26 August, Ranger’s battle group relieved Delta.

With their Indian Ocean operations now complete, Cook and the rest of her battle group sailed for Australia. Prior to their arrival, they conducted joint exercises with the Australian Navy, focusing predominantly on ASW and aviation war exercises. Cook subsequently visited the city of Bunbury for a few days of liberty (7-14 September 1987). While there, Cook’s crew received visitors, participated in receptions, and made liberal use of the town’s dial-a-sailor program, which offered local women the opportunity to escort members of the crew around town. It was not all fun and relaxation, however, as Cook’s inport emergency crew assisted the local fire department in extinguishing a blaze adjacent to the pier.

Cook and the rest of Battle Group Delta departed Western Australia for Subic Bay on 14 September. Arriving seven days later, Cook underwent five days of maintenance (21-25 September 1987) before sailing for San Diego. Briefly stopping in Pearl Harbor on 6 October to pick up 22 “Tigers,” she arrived back in San Diego on 13 October, thus concluding her deployment. HSL-35 swiftly disembarked and the crew received maximum leave. It was not until 15 November 1987 that the ship got underway for SoCal patrols. With a Coast Guard detachment embarked, Cook’s primary mission was to conduct drug interdiction operations. Over the course of the five-day period (15-20 November), she stopped a few suspect vessels, enabling the Coast Guard to search for drugs on board.

Cook began 1988 with a change of command and a nearly three-month drydocking selected restricted availability (DSRA) ahead of her. On 18 January, she entered Continental Maritime Shipyard in San Diego to begin her DSRA with a focus on overhauling and correcting her engineering equipment and weapon systems, as well as installing new equipment. One month later, on 26 February, she entered Steadfast for work on her shaft, sonar dome, and hull. After the DSRA ended on 23 April, Cook and her crew spent the next two months conducting drills and preparing for inspections.

In contrast to prior non-WestPac years, Cook did not venture north to Washington and Canada. Instead, she got underway on 14 June 1988 in company with Missouri (BB-63), Long Beach (CGN-9), John Young (DD-973), and McKlusky (FFG-41) for RimPac ’88, a six-week cruise (14 June-3 August) that involved joint exercises with U.S., Australian, Canadian, and Japanese naval units in and around Pearl Harbor. Cook participated in these evolutions as part of battleship Missouri’s battle group with HSL-35 Det. 4 embarked. Her first set of exercises took place from 24 to 30 June as part of surface action group comprised of Long Beach, the Australian oiler Success (OR.304), Parametta (FFH.154), and Restigouche. She subsequently conducted ASW operations as part of a mixed group comprising Canadian, Australian, and Japanese ships over the course of the next month (7-23 July).

Cook was due to return to San Diego on 2 August 1988, but a day before she arrived back, she was detached from the battle group to render assistance to Barbey, which lay in the water 50 miles behind Cook after losing all propulsion and electricity. Steaming back to Barbey, Cook lent assistance and made preparation to tow the moribund ship back to San Diego. Fortunately, Barbey was able to return to port under her own power after her crew successfully relit the boiler fires and started her engine.

Drills and inspections (INSURV, Combat Systems Assessment, ISIC Engineering Readiness Assessment, operational propulsion plant exam [OPPE], 3-M) largely consumed the rest of 1988 for Cook and her crew. There were, however, some notable exceptions including ship visit at Broadway Pier in downtown San Diego (23-25 September) and San Francisco’s Navy Fleet Week (11-19 October). The latter drew a crowd of nearly 100,000 people to see Cook, Ranger, and a number of other ships docked in the harbor. Cook herself tied up at Fisherman’s Wharf, enabling the crew to enjoy four days of liberty.

This revelry and relaxation of Fleet Week quickly gave for way to the stress of preparing for the OPPE and, equally significant, Cook’s ninth and final WestPac cruise. To prepare for the latter, Cook conducted battle group exercises with Ranger as part of Battle Group Echo (November 14-8). She then proceeded to pass her OPPE (December 14-6), ensuring that she would be ready to undertake her WestPac deployment.

After returning from holiday leave and upkeep, Cook conducted ASW, ASUW, and planeguard operations with Battle Group Romeo and its flagship, Ranger, on 22 January 1989. Following a period of maintenance availability and embarking HSL-35 Detachment 4, Cook and the rest of Romeo got underway for their WestPac deployment on 24 February, rendezvousing with Ranger en route to their planned stopover in Pearl Harbor (8-10 March). From there, they sailed to Subic Bay, arriving little over two weeks later for a maintenance period (26 March-1 April).

While en route to Singapore (4-6 April 1989), Cook was detached from Battle Group Romeo to conduct a passing exercise with the Indonesian frigate Fatahillah (361). The two ships also exchanged crew for hands-on training. Having completed the evolution, Cook rejoined her battle group and stopped at Singapore (7-11 April). They then made their way to the Indian Ocean for operations, followed by an inport stay (6-11 May) at Diego Garcia for maintenance availability alongside destroyer tender Puget Sound (AD-38). While operating near there, Cook and Buchanan (DDG-14) conducted a towing exercise. All was going according to plan until Buchanan’s towing hawser became fouled in Cook’s screw. No damage was sustained, but divers from Camden (AOE-2) were required to remove the hawser.

Cook’s Indian Ocean operations proved relatively routine. At the end of her patrol, Cook stopped in Muscat to conduct joint exercises with the Omani Navy (10-13 June), focusing primarily on formation steaming and ASUW exercises. Following this, Battle Group Romeo mainly conducted port visits, with Cook first sailing to Bunbury in the company of Buchanan (29 June-6 July) and then subsequently visiting Pattaya Beach, Thailand (15-19 July), and Hong Kong (24-28 July). Following another brief layover in Subic Bay (30 July-3 August), Cook embarked on her final voyage back to San Diego. As she had done when returning from prior deployments, she stopped first at Pearl Harbor to pick up some “Tigers” (15-17 August). She then proceeded to the California coast, stopping briefly in company with Camden and ammunition ship Shasta (AE-33) to offload her ammunition. Finally, she arrived in San Diego, debarking HSL-35 Det. 4. After nine overseas deployments which had seen Cook undertaking everything from evacuating southern Vietnamese refugees to conducting intelligence operations in the North Arabian Sea, her few remaining years in active service would largely be dedicated to conducting operations off southern California and the broader Pacific Coast.

On 1 October 1989, Cook transitioned from the Active Fleet to the Naval Reserve Force. While she no longer deployed abroad, Cook continued to undertake numerous training exercises, escort ships, and assist local law enforcement in preventing drug trafficking throughout the SoCal area. This was, however, delayed by nearly two months due to a crankcase explosion in the 1B ship’s service diesel generator on 2 October 1989, which forced Cook to remain in port until 20 November. After getting underway again, Cook spent the next three weeks assisting the Coast Guard with drug interdiction operations (27 November-18 December). With a Coast Guard detachment embarked, she stopped and investigated three ships, but made no arrests.

Following holiday leave and upkeep, Cook entered a planned maintenance availability (PMA) period at the Continental Maritime Yard in San Diego. Between 16 January and 27 March 1990, workers completed over 150 jobs including the installation of a Halon and AFFF bilge sprinkling systems, an overhaul of 1B boiler, renovation of the CIC, and the installation of CIWS and SPA 25G’s. Tests, inspections, and exercises (including an UNREP with USNS Kawishiwi [T-AO-146]) consumed the next month. By 11 May, Cook had returned to assisting law enforcement operations of the coast of Baja California.

On 3-6 June 1990, Cook made her way to Astoria, Ore., in the company of New Jersey to participate in exercise Criterion 90-17. Some Greenpeace activists attempted to bar the squadron’s passage by suspending themselves from the Astoria [Oregon] Bridge. After scouting the structure for a safe way through, Cook escorted New Jersey and other ships in her group upriver. Upon her return from Astoria, she escorted ex-Plunger (SSN-595) to Seattle from NSC Oakland, Calif. (13-18 June) and ex-Shark (SSN-591) from Seattle to San Francisco (20-24 September). The rest of the year was spent undertaking inspections, including preparations for the OPPE.

1991 proved to be a considerably more active year for Cook and her crew. On 15 January, Cook steamed north to the Nanoose operations area for a Nixie/Torpedo exercise. She planned to follow that up with a visit to Vancouver, but Greenpeace protests within the city caused its cancellation. Cook instead sailed for Esquimalt.

Following her return to San Diego, Cook once again participated in law enforcement operations in the southern Baja California area, identifying 40 contacts and conducting two boardings over the course of a week (20-28 February 1991). Nearly a month later (19-22 March), Cook participated in an ACAT with Vincennes (CG-49) and Lake Champlain (CG-57), as well as an UNREP with USNS Navasota (T-AO-107). She conducted further exercises throughout spring and summer, including refresher training at Pearl Harbor (9-27 April), joint exercises with the Japanese navy at COMPUTEX 91-5 (22-26 July), and participation in Varsity Player 91 with Duncan (FFG-10), Lewis B. Puller (FFG-23), and Hepburn (FF-1055) (5-21 August). Despite suffering a significant casualty to her service diesel generator on 21 August, Cook successfully completed the remaining inspections for the year, notably, the INSURV and ISIC Engineering Readiness Assessment.

Cook’s final year of service witnessed her making one final voyage to San Francisco on 9 January 1992. Following a two-day port visit (11-12 January), she made her way to Concord Naval Weapons Station to offload her torpedoes and ASROCs for the final time, as well as her 5-inch and small arms ammunition (14-16 January). Upon completion of this, Cook cruised to San Diego, with the crew taking advantage of the beautiful weather to hold one final “steel beach” picnic on Cook’s deck.

Cook entered her decommissioning availability on 27 January 1992. For the next three months, the crew worked to close out all spaces prior to her decommissioning ceremony on 30 April. Prior to this, on 28 February, Cook and her crew hosted Canadian destroyer Huron (DDG.281) during its port visit to San Diego. By 27 March, all spaces on Cook had been closed.

Cook was decommissioned on 30 April 1992 and stricken from the Navy Vessel Register on 11 January 1995. On 29 September 1999, she was transferred to the Republic of China (Taiwan) through the Security Assistance Program (SAP). Renamed Hai Yang (FFG.936), she served in the Taiwanese Navy until being retired in 1 May 2015.

During her service in the U.S. Navy, Cook received the Secretary of the Navy’s Meritorious Unit Commendation for extraordinary service three times, the Navy Expeditionary Medal, the National Defense Service Medal, the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal, the Humanitarian Service Medal (two awards), Vietnam Service Medal (two campaigns), the Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal, and the Sea Service Deployment Ribbon.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Cmdr. James R. Talbot, Jr. | 18 December 1971 |

| Cmdr. Carl A. Nelson | 13 April 1973 |

| Cmdr. Jerry C. McMurry | 4 April 1975 |

| Cmdr. Joseph B. Famme | 3 June 1977 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Martin J. Mayer | 27 June 1979 |

| Cmdr. Michael B. Ferguson | 3 July 1979 |

| Cmdr. Robert H. Joyce | 23 July 1981 |

| Cmdr. Donald J. Degreef | 2 July 1983 |

| Cmdr. Robert E. Lang | 19 October 1985 |

| Cmdr. Richard W. Kalb | 13 January 1988 |

| Cmdr. Larry E. Penix | 20 January 1989 |

Martin R. Waldman, Ph.D.

23 January 2018

Further Reading

Fischer, Benjamin. A Cold War Conundrum: The 1983 Soviet War Scare. Langley, VA: CIA, 1997.

Huchthausen, Peter and Alexandre Sheldon-Duplaix. Hide and Seek: The Untold Story of Cold War Naval Espionage. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Herman, Jan K. The Lucky Few: The Fall of Saigon and the Rescue Mission of the USS Kirk. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2013.

Westad, Odd Arne. The Cold War: A World History. New York: Basic Books: 2017.