The Navy Department Library

Finding of Facts, Opinion and Recommendations

The court, having thoroughly inquired into all the facts and circumstances connected with the allegations contained in the precept and having considered the evidence adduced, finds as follows:

FINDING OF FACTS

1. GENERAL FINDING: That explosions occurred at the U.S. Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, California, involving 429 tons of munitions (which contained 146 tons of high explosives and 10.75 tons of smokeless powder) on the ship pier, and 4,606 tons of munitions (which contained 1760 tons of high explosives and 199 tons of smokeless powder) on the S.S. E. A. BRYAN moored to the ship pier, at or about 2219, Pacific War Time, 17 July 1944, resulting in the total destruction of three vessels; namely, the S.S. E. A. BRYAN, valued at $1,600,000; the S.S. QUINAULT VICTORY, valued at $2,850,000; the US Coast Guard fire barge No. 60014-F of the value of $34,691.44; and the constructive total loss of the US YP MIAHELO II, of the value of $6,000, all the property of the US Government, and damage and destruction of other property of the US Government in the amount of $5,401,343.30; the total damage to US Government property amounting to $9.892,034.74; damage to the MS REDLINE owned by the Union Oil Company for which claim has been filed in the sum of $221,121.25; damage to small craft for which claims have been filed in the sum of $2,362.13, all of which original claims for damages to small craft have been delivered to the Board of Investigation for handling; the loss of 10 officers and 231 enlisted personnel of the US Navy and US Naval Reserve, of which the bodies of 7 officers and 34 enlisted men have been identified, and of which 3 officers and 197 enlisted personnel are missing; the death of one enlisted man of the US Marine Corps Reserve, his body having been identified; the loss of 5 enlisted personnel of the US Coast Guard and US Coast Guard Reserve, of which the bodies of 2 have been identified and of which 3 are missing; the loss of 67 members of the US Maritime Service, of which the bodies of 3 have been identified and 64 are missing; the loss of 3 civil service employees of the US Navy, the body of one having been identified and 2 are missing; and the death of 3 civilians, their bodies having been identified; the total identified dead numbering 51 and the total missing numbering 269; and personal injuries to 4 officers and 233 enlisted men of the US Navy and US Naval Reserve, 6 enlisted personnel of the US Marine Corps and US Marine Corps Reserve, 4 enlisted personnel of the US Coast Guard and US Coast Guard Reserve, 5 members of the US Maritime Service, 22 civil service employees of the US Navy, and 3 civil service employees of the US Army; and personal injuries, superficial and permanent, to 113 civilians, of whom 69 have filed claims, 54 of the latter having designated damages in the total sum of $121,999.04, all of which claims for death and personal injuries have been delivered to the Board of Investigation for handling pursuant to instruction of the Convening Authority.

2. INTENT - FAULT - NEGLIGENCE: That the evidence does not show that there was any intent, fault, negligence, or inefficiency of any person or person in the naval services or connected therewith, or any other person, which caused the explosions.

3. GENERAL FACTS CONCERNING NAVAL MAGAZINE: That the general facts concerning the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, up to the time of ht explosion were as follows:

(1) The US Naval Magazine, Port Chicago was formally established by an order of the Secretary of the Navy dated 27 June 1942, and was commissioned on 30 November 1942. It was designed for a particular function and in general layout conformed to latest accepted standards for this type of establishment.

(2) The facilities of Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, had been expanded until the saturation point had been reached. Because of a physical lack of space, Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, could not be further expanded. There were no other munitions handling facilities available.

(3) Construction of the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, was authorized in June, 1942, and the Public Works Officer, Twelfth Naval District, was designated as officer in charge of construction. The location of Port Chicago was recommended by a board appointed by the Commandant, Twelfth Naval District, for that purpose. The site selected was well chosen. Port Chicago was remote from industrial activities, in a sparsely settled area, had deep tide water along the northern boundary, and was served by two transcontinental railways. There was room for further expansion.

(4) Originally the principle facilities contemplated were: a ship-loading pier; a barge loading pier; barricaded railway spurs for the storage of explosives; a railway system connected to the trunk line railroads; an administration building; and, a marine barracks. After construction was started a decision was made to do the work of loading with enlisted men, as an adequate force of commercial stevedores could not be guaranteed. The buildings provided were the minimum required for housing and feeding the men. The lack of officer messing facilities, recreation building for enlisted personnel, laundry, etc., coupled with the remoteness of the station and the lack of adequate personal transportation facilities made the problem of morale a most difficult one.

(5) The constantly increasing need for transshipping of ammunition required repeated revisions of the estimated handling requirements. There is even now a program for increasing the capacity and for adding storage facilities. All increases of capacity required additional officers and men, which, in turn required additional collateral buildings for housing, recreation, messing, etc. Efforts were made by the commanding officer to build up an adequate and effective station. These effort were severely handicapped from time to time by the lack of authorization for this collateral equipment which was vitally needed for the personnel assigned.

(6) The shiploading pier was built especially for handling explosives from railway cars directly into deep water ships. The original design was inadequate and was changed from time to time as a result of experience. The pier in its final state was completed in May, 1944, when two ships could be handled simultaneously. Additional facilities consisting of a marginal pier with two shiploading berths in tandem was nearly completed at the time of the explosion, and a third two-ship pier had been authorized.

(7) Prior to the explosion, the number of ships assigned to load at Port Chicago was not sufficient to fully utilize the facilities available.

b. FUNCTION:

(1) The Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, was designed to receive munitions by rail and load them from the cars directly into seagoing vessels or barges. It was primarily a transfer activity. It was not intended as a storage, supply, manufacturing, inspection, or repair facility. The magazine's responsibility started with the receipt of loaded railway cars and ended when the cargo had been stowed in ships or barges.

c. ORGANIZATION:

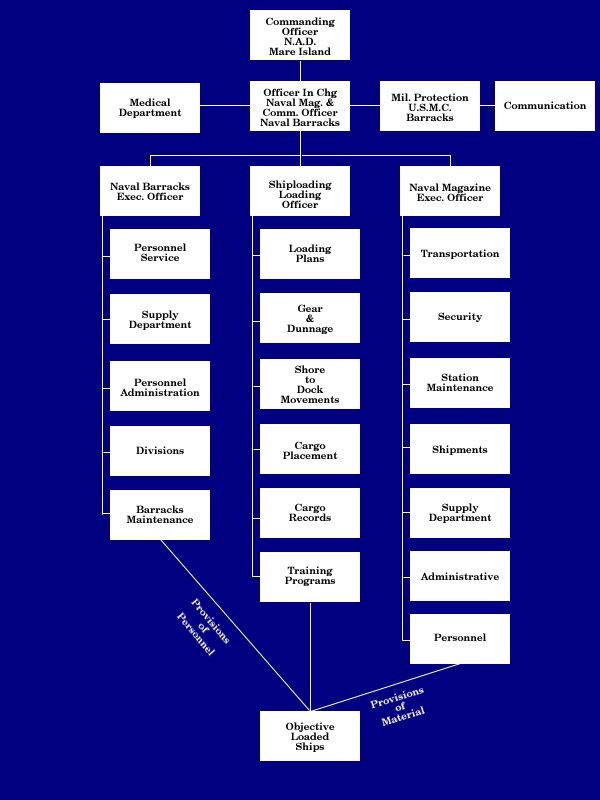

(1) The Naval Magazine and the Naval Barracks, Port Chicago, were annexes of the Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island. The commanding officer, Naval Barracks, Port Chicago, was also the officer in charge of the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago. His immediate superior for both these activities was the Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island. The internal organization that was in fact in use on 17 July 1944, at the time of the explosion, is shown in the diagram on Page No 1201:

(2) Policies were prescribed by the Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, and executed by the Commanding Officer, Naval Barracks, and the Officer in Charge, Naval Magazine, Port Chicago.

d. OFFICER PERSONNEL:

(1) At the beginning of the national emergency, the Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, recognized the need for additional trained officers. He made continued efforts to obtain trained officers and officer candidates with suitable background. The constantly expanding activities of the Naval Ammunition depot and the commissioning of and subsequent constantly expanding activities at Port Chicago were hampered until very recently by a lack of trained officers. The most glaring deficiencies were the lack of officers qualified to train and administer the enlisted personnel, and of officers with explosive handling experience. Those officers who started operations at Port Chicago got all their experience at Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island. At the time of the explosion an adequate number of qualified officers were attached.

e. TRAINING OF OFFICERS:

(1) The original group of officers had little stevedoring experience, none with handling enlisted personnel, and none with explosives. They were trained by various means before the commissioning of Port Chicago, such as --

(a) Attending Port Director's school, which dealt primarily with office work in connection with shipping.

(b) Duty under instruction, observing the activities of the production division at Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, for familiarization with details of ammunition.

(c) Working with experienced officers and ordnancemen at Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, in actual shiploading.

(d) Visits to commercial shiploading points in the San Francisco Bay area and elsewhere.

(e) A course of instruction at Great Lakes in negro psychology.

(2) After undergoing phases of the above (it was not the same for all officers), they were sent to Port Chicago and started shiploading operations. There, all the officers had to further perfect themselves by actual experience.

(3) Later, as new officers became available, they were assigned as assistant division officers under instruction, and learned by practical experience. These officers were being trained to take charge of the new divisions formed as a result of expansion.

(4) A comprehensive source of instruction for all officers was conceived in recent months and was rounding into shape, but had not been put into effect at the time of the explosion.

f. ENLISTED PERSONNEL:

(1) The men comprising the ordnance battalions were supplied from other organizations and from the various training stations. The men received from the training stations were those remaining after the top 25 to 40 percent had been selected for other assignments. From time to time, Port Chicago was required to transfer drafts of men with clear records, thus further reducing the general level of those remaining.

(2) There was a continuing expansion of the work load and a necessity for training and absorbing additional green men. There is and has been a serious lack of petty officer material. The policy of taking out the best men at the training stations operated to deprive Port Chicago of the normal source of petty officer materials. The general classification test averaged 31.y, which placed the men comprising these ordnance battalions at Port Chicago in the lowest twelfth of the Navy.

(3) The handling of the enlisted personnel stationed at Port Chicago presented many problems. These enlisted personnel were unreliable, emotional, lacked capacity to understand or remember orders or instructions, were particularly susceptible to mass psychology and moods, lacked mechanical aptitude, were suspicious of strange officers, disliked receiving orders of any kind, particularly from white officers or petty officers, and were inclined to look for and make an issue of discrimination. For the most part, they were quite young and of limited education.

g. TRAINING OF ENLISTED PERSONNEL:

(1) Because of the level of intelligence and education of the enlisted personnel, it was impracticable to train them by any method other than by actual demonstration. Many of the men were incapable of reading and understanding the most simple directions. Division officers were responsible for the actual training of the men and they carried out their duties by personally instructing and demonstrating with the material being handled, the proper methods of procedure. The division officers attempted to impress on the men the need for care and safety, and the highly dangerous nature of material being handled.

(2) A training winch had been in operation since March, 1944. The winch men were trained on the training winch for one week and then given further training on the ships until their division officers pronounced them qualified.

(3) Lectures were given to one division each day on safety precautions and other phases of their work. There was in the course of preparation a regularly prescribed curriculum for the instruction of all men.

(4) Efforts were made by the officers to bring home to the men the necessity for care in the handling of explosives.

(5) The original divisions before being sent to Port Chicago had been instructed along with their officers by working with experienced ordnancemen at Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, in actual ship-loading operations. A nucleus for any new division was drawn from these divisions. New drafts made up the vacancies in the old divisions left by withdrawing this nucleus, and also made up the remainder of the new division. Thus, new men were worked in with the older men.

(1) Because of the isolation of Port Chicago, the lack of adequate housing and the keen competition for civil service and civilian workers of all categories in this area, it was not possible to secure an adequate number of competent civil service employees.

(2) Prior to starting operations at Port Chicago, the experienced civil service ordnancemen had assisted in the training of the officers and enlisted personnel of the ordnance battalions at Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, California. This assistance was continued for a short time at Port Chicago when operations started there, until the services of these ordnancemen could no longer be spared and they were returned to the Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island. Additional trained, competent civil service personnel in the ratings required were not available.

i. POLICIES OR DOCTRINES IN EFFECT:

(1) The basic policy of the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, required that the ships be loaded on schedule, using the safest means that could be devised.

(2) A tremendous problem was involved in handling safely the large quantities of ammunition and explosives. This problem was magnified by the character of enlisted personnel and the caliber of officer supervision available. The commanding officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, kept the Bureau of Ordnance and other bureaus advised of his difficulties and made repeated requests and recommendations concerning both officer and enlisted personnel and the necessary increases in facilities.

(3) He and his subordinates studied the various handling methods and gear in use by similar activities. They conducted experiments toward improving these methods and the gear used. From these studies and experiments a standard method of handling each item was evolved. In arriving at these standard methods, safety was given primary consideration. This program of study and experimentation was a continuing process.

(4) The Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, required that ships be loaded expeditiously on a three-shift basis to meet the schedules of required ammunition shipments.

(5) The ordnance battalions were administered and trained in the same manner as are all other enlisted men in the Navy. There was no discrimination or any unusual treatment of these men.

(6) An order was in effect prohibiting the unnecessary accumulation of high explosives on the pier.

(7) Under special conditions the Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, would permit vessels to take fuel while at the Port Chicago pier.

j. SECURITY:

(1) Security from unauthorized intrusion was provided by a marine sentry system. Security on the waterfront was provided at night by the Coast Guard patrol boats. Internal security was supplied by roving patrols within the station and by the placing of cars containing explosives under guard.

(2) Security from fires was provided by a fire watch in the barracks and a fire engine stationed in the barracks area, and a fire engine manned by the marines and stationed near the marine barracks in the explosive area, self-powered pumpers on the barge loading pier and on the shiploading pier and a Coast Guard fire barge secured at the end of the shiploading wharf.

(3) A system of passes, the escorting of visitors, and the inspection of packages was in force.

(4) There were no means provided at Port Chicago for defense against enemy attack.

(5) Smoking was prohibited, except in certain specified places.

(6) Automobiles and trucks were not permitted on the pier beyond the pier office.

(7) A manual fire alarm system was installed throughout the station.

4. OTHER ACTIVITIES: The other activities had duties pertaining to operations at Port Chicago as follows:

a. SERVICE FORCE SUBORDINATE COMMAND:

(1) Ammunition and explosive requirements emanated from the local office of the Service Force Subordinate Command which arranged with the Bureau of Ordnance for the arrival at Port Chicago of the desired cargo at a specified time. Close liaison was kept with the Port Director's office, which arranged for the necessary ships at the specified time.

b. PORT DIRECTOR:

(1) On request from the Service Force, the Port Director arranged for ships to be at Port Chicago in condition to receive cargo at specified times. This included inspection of ships for adequacy of gear, cleanliness, and general readiness for loading; however, some ships did arrive at Port Chicago not ready for loading.

(2) In collaboration with Port Chicago and Service Force, the Port Director drew up a loading plan for each ship and, as agents for the operators of the ships, submitted it to the Captain of the Port for loading permit.

(3) During loading, a representative of the Port Director observed details of stowage so that ships would leave Port Chicago in proper condition for further loading or for sea. In cases where deviations from the approved loading plan were necessary, he arranged for a waiver.

(1) The Captain of the Port issued permits for loading. His authority in the form of a waiver was required for deviations from the loading plan.

(2) The Captain of the Port inspected ships for fire and security hazards, poor equipment, foreign substance, personnel check, and as far as possible, the condition of winches, booms, and handling gear, and other factors in connection with general readiness for loading; however, some ships did arrive at Port Chicago not ready for loading.

(3) During loading, unless declined in writing by the commanding officer of a naval activity, the Captain of the Port provided a loading detail whose responsibility started when cargo was under the boom. This detail was a law-enforcement detail with veto power--could stop loading until any unsafe practices were corrected, or improper stowage rectified. This detail was responsible only to the Captain of the Port. The Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, had declined such detail in writing and not detail was present at Port Chicago on 17 July 1944.

d. BUREAU OF ORDNANCE:

(1) The Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, and the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, were Bureau of Ordnance stations. Funds for them were allocated and their work was controlled by that bureau. The handling, processing, issue, and shipment of explosives was done in accordance with directives issued by that bureau. The policies and methods authorized by the Bureau of Ordnance were carried out at the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago.

5. OPERATION DETAILS: That the details of operations at Port Chicago were as follows:

a. RECEIPT AND STORAGE OF AMMUNITION:

(1) Ammunition and explosives were received at the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, by rail in carload lots. These had been shipped in accordance with directives of the Bureau of Ordnance from various storage depots and filling plants. Normally, shipments were scheduled to arrive for loading in a particular ship. There were very limited facilities at Port Chicago for unloading explosive material and placing it in storage. This required a very nice adjustment of schedules. If the ships were late, more cars than could be handled in barricades would accumulate at Port Chicago. If rail delivers were delayed, the shiploading would be delayed.

b. DETAILS OF MOVING AMMUNITION TO PIER:

(1) After the loading plan had been approved, the magazine planning officer issued a work sheet for each loading. This work sheet was used by the magazine transportation officer to work out a sequence of delivery of cars to the pier. The cars would actually be sent to the pier on the orders of the loading officer. Normally, these cars reached the pier sealed just as they had been received on the station. Occasionally some were opened just before proceeding to the pier and some of the dunnage and bracing removed.

(2) The pier had three tracks, and at each edge a loading platform 18 feet wide of the height of the car floor. Cars were spotted opposite the holds into which they material was to be loaded. The center track was used for switching. Occasionally when one car was empty, in order to prevent disrupting the loading of all the hatches, cars were spotted opposite a hatch on the center track and material handled through the empty car adjacent to a hatch. The physical limitations of the pier prevented any unnecessary concentration of explosives on the pier. When loading two ships simultaneously, there was considerable crowding and congestion on the pier.

(3) Shifting of cars, that, is, taking the empty cars away and brining in full cars, resulted in a loss of loading time and insofar as possible was done during meal hours.

c. DETAILS OF LOADING INTO VESSELS:

(1) The material was taken out of the cars, placed under the ship's booms, hoisted on board, and stowed in the holds.

(2) The details of each of these operations depended on the material being loaded. The method used for each item was the result of careful study and consideration and was under the control of the loading officer.

(3) Instructions were in effect on 17 July 1944 that the "Regulations Governing Transportation of Military Explosives on Board Vessels during the Present Emergency",. published by the US Coast Guard (Nav.C.G.), dated 1 October 1943, were to be followed in principle and that those parts relating to the separation of carious classes of explosives and stowage of explosives in merchant vessel must be followed in detail. Violations of some of these regulations occurred. These violations consisted of rolling depth charges, hoisting depth charges in nets, failure to use a mattress or [thrum] mat at times, and the wearing of shoes shod with uncovered nails.

(4) These violation were not haphazard or due to ignorance. Violations occurred either because it was not possible to comply and gel the material loaded or because the method used was considered the safest. The methods used were in accordance with generally accepted naval practice.

(5) The general and primary safety requirement that all explosives must be handled carefully was insisted on.

(6) Pertinent available information required by officers at the Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, in the performance of their duties was disseminated.

(7) Careless and some unsafe acts by individuals have occurred in the past. (The Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, recognized this and issued timely memoranda and orders that such practices be corrected.) Unsafe practices and speed at the expense of safety were not permitted by anyone in authority. Efforts were made t determine the safest way, t make that method standard, and to have the work done carefully.

(8) In recent months, items of munitions damaged in handling at Port Chicago and returned to the Naval Ammunition Depot for repairs or disposition decreased materially.

(9) The placement of the material in the vessels was governed by the loading plan. The shoring was carefully and skillfully done.

(10) The Port Director had a representative aboard each ship, but not continuously. He inspected the placement and shoring. There is no evidence of any disagreement that was not reconciled on the spot between the representative of the Port Director and the loading officer.

(11) Many of the loading practices observed by witnesses at the various terminals were not used at Port Chicago, as responsible officers did not consider them suitable.

(12) The pier was well lighted and night loading presented no particular difficulties.

d. DETAILING OF PERSONNEL FOR CURRENT JOB:

(1) The ordnance battalions were divided into loading divisions of about 100 men. These divisions were further subdivided into platoons, five platoons to a division. Each platoon was designed to work one hatch. The platoons were further divided into squads, one squad under a petty officer or leading man on the pier to take the material from the car and put it in the gear being used for hoisting, and the other squad under a petty officer in the hold to receive the material and stow it. each division provided its own checkers, winch men, hatch tenders, and carpenter's mates for dunnage. Unnecessary men were not permitted on the pier. Reliefs took place off the loading pier.

(2) Divisions were detailed as a unit to load a ship for eight hours with one hour off for meals. Divisions worked for three days, had a day barracks' duty, worked another three days and then had liberty from 5 p.m. to 7 a.m. of the second day following. Thus, they worked seven hours a day for six out of eight days.

e. DETAILS OF LOADING ORGANIZATION ON THE PIER:

(1) The senior loading officer was in charge of all loading. Neither he nor his senior assistant remained on the pier at all times. They made frequent inspection trips to the pier. One of the junior loading officers was on the pier at all times. All loading officers had been carefully selected and were considered qualified by the Officer in Charge. The division officers and their assistants were required to be with their divisions at all times when the division was engaged in loading operations, and exercised direct supervision over their men. The loading division petty officer had a roving detail and assisted the division officer.

(2) The planning officer, his assistant, the officer in charge, and the dunnage officer made frequent visits to the pier during loading operations.

(3) There was a record maintained and posted of the tonnage loaded by each division. the Commanding Officer, Naval Ammunition Depot, considered 10 tons per hatch per hour as a desirable and attainable loading rate. most division officers considered this too high.

(4) The rate of tonnage attained at Naval Magazine, Port Chicago, by the ordnance battalions in the months prior to the explosion was 8.2 tons per hatch per hour. Commercial stevedores at the Naval Ammunition Depot, Mare Island, averaged 8.7 tons per hatch per hour.

(5) The loading platforms were congested when mechanical equipment was being used or dunnage handled. The pier in general was congested when two ships were loading simultaneously.