The Navy Department Library

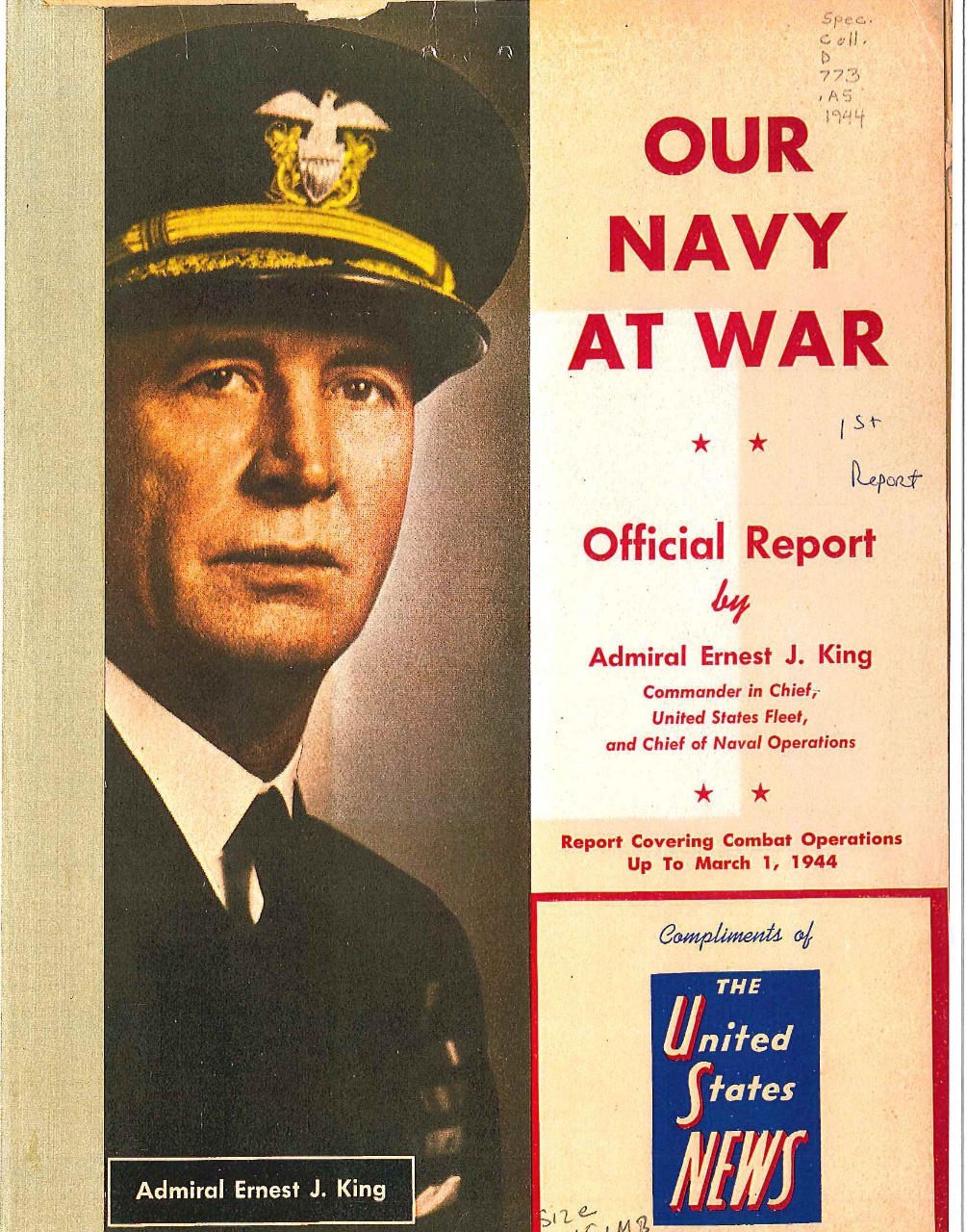

OUR NAVY AT WAR

Official Report by Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

Report Covering Combat Operations up to March 1, 1944

PDF Version [15.1MB]

OUR

NAVY

AT WAR

A Report to the Secretary of the Navy

Covering our Peacetime Navy and our Wartime Navy

And including combat operations up to March 1, 1944

By ADMIRAL ERNEST J. KING, U.S.N.

Commander in Chief, U. S, Fleet,

And Chief of Naval Operations

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL |

Page 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | 3 |

| -I- | |

| THE PEACETIME NAVY | 3 |

| Prior to the War in Europe | 3 |

| As Affected by the War in Europe | 5 |

| -II- | |

| THE WARTIME NAVY | 7 |

| Fighting Strength | 7 |

| Armaments | 7 |

| Personnel | 13 |

| -III- | |

| COMBAT OPERATIONS | 20 |

| General | 20 |

| Strategy | 24 |

| The Pacific Theater | 25 |

| The Mediterranean Theater | 50 |

| -IV- | |

| TEAMWORK | 55 |

| The Navy Team | 55 |

| The Army and Navy Team | 55 |

| The Allied Team | 55 |

| -V- | |

| CONCLUSION | 56 |

27 March 1944

Dear Mr. Secretary,

In view of the importance and complexity of our naval operations and the tremendous expansion of our naval establishment since we entered the war, I present to you at this time a report of progress.

It is of interest to note that the date of this report happens to be on the 150th anniversary of the passage by Congress of a bill providing for the first major ships of the United States Navy—the 44 gun frigates Constitution, United States, President and Chesapeake, and the 36-gun frigates Constellation and Congress.

This report includes combat operations up to March 1, 1944. I know of no reason why it should not be made public.

ERNEST J. KING

Admiral, U.S. Navy,

Commander in Chief, United States Fleet

And Chief of Naval Operations

3

Introduction

For more than two years, the United States has been engaged in world-wide war. Our geographical position, our wealth, resources and industrial development, combined with an unfaltering will to victory have established and enhanced our position as one of the dominant powers among the United Nations. As such we have been closely and deeply involved with our Allies in all the political, economic and military problems and undertaking which constitute modern war. Historically, the conduct of war by allies has rarely been effective or harmonious. The record of the United Nations in this regard, during the past two years, has been unprecedented, not only in the extent of its success but in the smooth working and effective cooperation by which it has been accomplished. As one of the United Nations, the United States has reason to be proud of the inter-Allied aspects of its conduct of the war, during the past two years.

As a national effort, the war has shown the complete dependence of all military undertakings on the full support of the nation in the fields of organization, production, finance, and morale. Our military services have had that support in a full degree.

The Navy has also had full support from the nation with respect to manpower. Personnel of our regular Navy, who, in time of peace, serve as a nucleus for expansion in time o war, now represent a small portion of the total number of officers and men. About ninety per cent of our commissioned personnel about eighty per cent of our enlisted personnel are Naval Reserves, who have successfully adapted themselves to active service in a comparatively short time. Thanks to their hard work, their training, and their will become assets their performance of duty has been uniformly as excellent as it has been indispensable to our success.

As to the purely military side of the war, there is one lesson which stands out above all others. This is that modern warfare can be effectively conducted only by the close and effective integration of the three military arms, which make their primary contribution to the military power of the Nation on the ground, at se, and from the air. This report deals primarily with the Navy’s part in the war, but it would be an unwarranted, though an unintended, distortion of perspective, did not the Navy record here its dull appreciation of the efficient, whole-hearted and gallant support of the Navy’s efforts by the ground, air and service forces of the Army, without which much of this story of the Navy’s accomplishments would never have been written.

During the period of this report, the Navy, like the full military power of the Nation, has been a team of mutually supporting elements. The Fleet, the shore establishment, the Marine Corps, the Coast Guard, the Waves, the Seabees, have all nobly done their parts. Each has earned an individual “well-done”-but hereafter are all included in the term, “The Navy.”

I –Peacetime Navy

PRIOR TO THE WAR IN EUROPE

The fundamental United States naval policy is “To maintain the Navy in strength and readiness to uphold national policies and interests, and to guard the United States and its continental and overseas possessions.”

In time of peace, when the threats to our national security change with the strength and attitude of other nations in the world who have a motive for making war upon us and who are--or think they are--strong enough to do so, it is frequently difficult to evaluate those threats and translate our requirements into terms of ships and planes and trained men. It is one thing to say that we must have and maintain a Navy adequate to uphold national policies and interests and to protect us against potential enemies, but it is another thing to decide what is and what is not the naval strength adequate for that purpose.

In the years following World War I, our course was clear enough—to make every reasonable effort to preserve world peace by eliminating the causes of war and failing in that effort, to do our best stay clear of war, while recognizing that we might fail in doing so. For a number of years, the likelihood of our becoming involved in a war in the foreseeable future appeared remote, and our fortunate geographical position gave us an added sense of security. Under those circumstances, and in the interest of national economy, public opinion favored the belief that we could get along with a comparatively small Navy. Stated in terms of personnel this meant an average of about 7,900 commissioned officers, all of whom had chosen the Navy as a career, and 100,000 enlisted men more or less.

This modest concept of an adequate Navy carried with it an increased responsibility on the part of the Navy to

4

maintain itself at the peak of operational and material efficiency, with a nucleus of highly trained personnel as a basis for war time expansion.

For twenty years in its program of readiness, our Navy has worked under schedules of operation, competitive training and inspection, unparalleled in any other Navy of the world. Fleet problems, tactical exercises, amphibious operations with the Marines and Army, aviation gunnery, engineering, communications were all integrated in a closely packed annual operation schedule. This in turn was supplemented by special activities ashore and afloat calculated to train individuals in the fundamentals of their duties and at the same time give them the background of experience so necessary for sound advances in the various techniques of naval warfare. Ship competitions established for the purpose of stimulating and maintaining interest were climaxed by realistic fleet maneuvers held once a year, with the object of giving officers in the higher commands experience and training in strategy and tactics approximating these responsibilities in time of war.

Our peacetime training operations, which involved hard work and many long hours of constructive thinking, were later to pay us dividends. For example, it would be an understatement to say merely that the Navy recognized the growing importance of air power. By one development after another, not only in the field of design and equipment, but also in carrier and other operational techniques—such as dive bombing—and in strategic and tactical employment, the United States Navy has made its aviation the standard by which were to make aviation the sine qua non of modern warfare. It may be stated here, with particular reference to naval aviation, that the uniform success which has characterized our naval air operations is unmistakably the result of an organization which was based on the conviction that air operations should be planned, directed and executed by naval officers who are naval aviators, and that in mixed forces naval aviation should be adequately represented in the command and staff organization.

Size and Composition

The effects of treaty limitations on our Navy are too well known to require more than a brief review. In 1922, under the terms of the Washington Arms Conference, limitations upon capital ships and aircraft carriers were agreed upon, the ratio established being five for the United States, five for Great Britain, and three for Japan. Pursuant to that treaty, the United States scrapped a number of battleships, but was permitted to convert the Lexington and Saratoga, then under construction as battle cruisers, to aircraft carriers. Whatever the other effects of the treaty, that particular provision has worked to our advantage because those two ships, as battle cruisers, would now be obsolescent, and as aircraft carriers they were—and the Saratoga still is—effective units of our fleet.

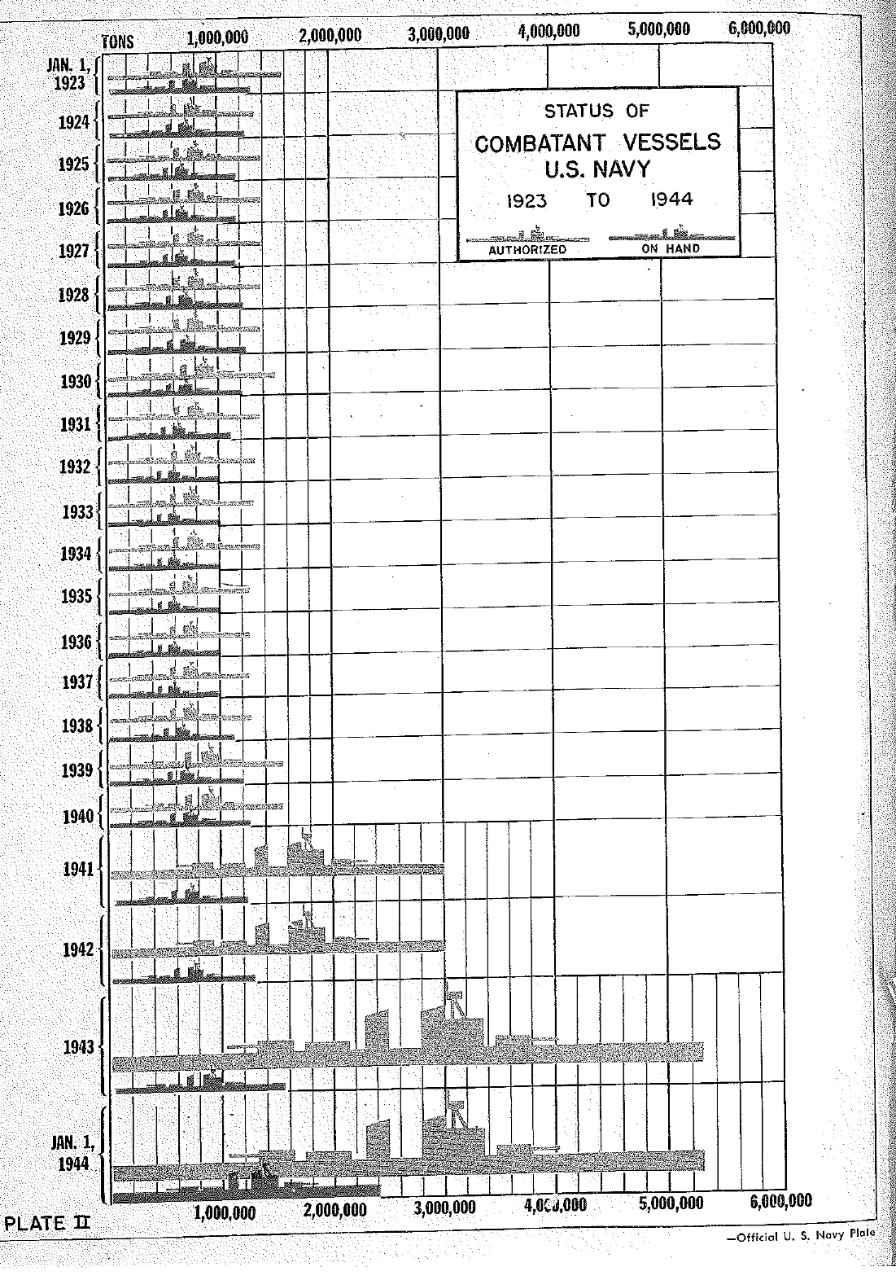

In 1930, at London, the parties to the 1922 treaty agreed upon further limitations, this time with respect to cruisers, destroyers and submarines. As a result of these two treaties, which reflected world conditions at the time, and also because of our decision to maintain our Navy at considerably less strength than that allowed by the treaties, we experienced a partial building holiday that threw our small construction program out of balance. Except for cruisers, hardly any combatant ships (no battleships or destroyers) were added to our fleet during that period, and few were under construction. In size, therefore, our Navy remained static, with certain types approaching obsolescence. Moreover, advances in the science of naval construction were hampered by the lack of opportunity to prove new designs. As the chart (front inside cover, Plate 2) indicates, our naval strength was low ebb during the year 1927.

Our failure to build progressively was a mistake which it is to be hoped to build will never be repeated. When a total building holiday in any type of ship is prolonged, and there is no opportunity to proceed on a trial and error basis, our designers are placed under handicaps taking years to overcome.

In 1924, and again in 1929, in response to representations to the effect that we were dangerously deficient in cruisers even in a world at peace, the Congress authorized the construction of a number of cruisers. These were appropriated for from time to time, as were ships of certain other types (except battleships), usually one or two at a time.

In 1933, our building program was stepped up materially by the authorization for the construction of two new aircraft carriers, four more cruisers, 20 destroyers and four submarines. The two carriers were considerably different in design from those previously built. The other types were more evolutionary as to new features, with the possible exception of the Brooklyn class of cruisers, which were to a degree a departure from former light cruisers, both as to ship design and armament. These cruisers were notable for their six-inch guns which combined light but strong construction with rapid loading, giving them a volume of fire far greater than any other light cruisers then--or now—in existence.

In the previous year, eight destroyers of the Farragut class had been laid down. These were the first of a long series of new designs which had been improved in each succeeding class up to the latest type laid down in 1943. The 1933 program, which was considered large at the time, used the Farragut type of armament, not only for destroyers but for the broadside batteries of the larger ships, because of the five-inch 38 caliber dual purpose gun which, because of its power, reliability and extremely rapid loading proved to be the best naval anti-aircraft gun of comparable caliber.

In March, 1934, the Congress authorized but did not appropriate for a Navy of treaty strength.

In 1935, in anticipation of making replacements under the terms of the treaties, work was begun on the design of battleships of the North Carolina class. Original designs (completed in 1937) included many features which have proved to be of great importance in the war; namely, increased armor protection around important control stations, modern five-inch anti-aircraft weapons, good torpedo protection, and excellent speed and steering qualities for rapid maneuvering. Contract designs for the South Dakota and Iowa classes were completed in 1938 and 1939, respectively. Most of these ships did not come into service until after the war had been declared.

The 6,000-ton Atlanta class cruisers, featuring powerful antiaircraft batteries, were designed in 1937.

In 1938, foreseeing the submarine menace, an experimental

6

attack on Britain. In view of that alarming situation, the Congress passed the so-called Two-Ocean Navy Bill, which was signed by the Presidential on July 19, 1940. The increase in our naval strength authorized by this Act was 1,325,000 tons of combatant ships—by far the largest naval expansion ever authorized. This authorization was followed by the necessary appropriations in due course, and in the making, we had a Navy commensurate with our needs.

The Destroyer—Naval Base Exchange

During the summer of 1940, the Battle of Britain was in its initial stages and the German submarine campaign had been prosecuted with telling effect. At the beginning of the war Great Britain had suffered severely from the general attrition of operations at sea, particularly in destroyers in the Norwegian campaign and during the retreat from Dunkirk. Faced with this situation, Great Britain entered into an agreement with the United States, under the terms of which 50 of our older destroyers no longer suited for the type of fleet service for which they had designed, but still adequately suited for antisubmarine duty, were exchanged for certain rights in various localities suitable, for the establishment of Naval bases in the Atlantic area, acquired in return for the 50 destroyers, we were granted, “freely and without consideration,” similar rights with respect to the leasing of bases in Newfoundland and Bermuda.

This acquisition of bases operated to advance our sea frontier several hundred miles in the direction of our potential enemies in the Atlantic, and as the bases were leased for a term of 99 years, we could profit by their strategic importance to the United States not only immediately, but long after the crisis responsible for the exchange.

The bases thus obtained by the United States were briefly as follows:

BRITISH BASES REQUIRED

| Location | Facility Established |

| Antigua, B.W.I. | Naval Air Station |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| British Guiana, S.A. | Naval Air Station |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| Jamaica, B.W.I. | Naval Air Station |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| St. Lucia, B.W.I. | Naval Air Station |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| Bermuda, B.W. I. | Naval Air Station |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| Great Exuma, Bahamas | Naval Air Station |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| Newfoundland | Naval Operating Base |

| Naval Air Station | |

| (Sea Plane Base, Air Field) | |

| Trinidad | Naval Operating Base |

| Naval Air Station | |

| (Sea Plane Base) | |

| Lighter-than-Air-Base | |

| Radio Station |

Lend-Lease and its Implementation

On March 11, 1941, the so-called “Lend-Lease” Act was signed by the President. The provisions and effects of that Act are too well known to require comment in this report. Naturally, we were unwilling to see a large part of the material built with our labor and money lost in transit, and our only recourse was to give the British assistance in escorting the convoys carrying that material within North American waters.

Incident to our decision, the United States entered into an agreement with Denmark on April 9, 1941, relative to the defense of Greenland, and on that day our Marines were landed there to prevent its being used by Axis raiders. The Coast Guard cutter Cayuga had already landed a party there to conduct a survey with respect to airfields, seaplane bases, radio stations, meteorological stations, and additions to navigation, and on the 1st of June, the first of the Greenland patrols was organized consisting chiefly of Coast Guard vessels and personnel.

On May 27, 1941, an unlimited national emergency was proclaimed by the President.

On July 7, 1941, the United States Marines were landed in Iceland and relieved some of the British forces stationed there.

On August 11, 1941, on board the USS Augusta, the President and Prime Minister of Great Britain agreed upon a joint declaration covering the principles of mutual interest to the two countries.

For some months, for the purpose of ensuring safe passage of goods shipped under the provisions of the Lend-Lease Act, our naval forces had been patrolling waters in the vicinity of the convoy routes, and had been broadcasting information relative to the presence of raiders. On September 4, 1941, the USS Greer, a four-stack destroyer was enroute to Iceland, with mail, passengers and freight. When about 175 miles south of Iceland, she detected a submarine ahead. The submarine fired a torpedo at her and missed, whereupon the Greer counterattacked with depth charges. Another torpedo was fired at the Greer but it also missed, and the Greer continued to Iceland. As a result of this incident, our Naval forces were ordered by the President to shoot on sight any vessel attempting to interfere with American shipping, or with any shipping under American escort.

On October 15, the USS Kearny, a new destroyer, one of a number of vessels escorting a convoy from Iceland to North America, was torpedoed amidships. Eleven of her crew were killed and seven were wounded, and the ship was badly damaged but able to make port.

On October 30, the USS Salinas, a tanker, was hit by two torpedoes about 700 miles east of Newfoundland. There were no casualties to personnel, and the Salinas reached port safely.

On October 31, in the same vicinity the USS Reuben James, another old destroyer, was struck amidships by a torpedo. The ship was broken in two; the forward part sank at once, but the after part stayed afloat long enough to enable 45 men to reach the deck and launch life rafts from which they were rescued. About 100 men were lost in this sinking.

Whatever the situation technically, the Navy in the Atlantic was taking a realistic viewpoint of the situation. During the month of November, further steps were taken to enable our naval forces to meet the steadily growing emergency. On November 1, the Coast Guard was made a part of the Navy, and at about the same time nine Coast Guard cutters were transferred to the British. On November 17, section 2, 3 and 6 of the Neutrality Act of

7

1939. were repealed by an act of Congress, thereby permitting the arming of United States merchant vessels and their passage to belligerent ports anywhere.

Another effect of the European war, of major importance to the United States, was the alliance by which on Sept. 27, 1940, Japan’s policy of expansion would conflict with our interests in the Pacific. Recognition of that possibility, plus Japan’s growing naval strength, were indicated by her being a party to the 1922 treaty on limitation of armaments, and to subsequent treaties dealing with that subject.

At the time of the 1922 treaty Pearl Harbor and Manila were fortified bases, and Guam was being fortified. None of our other Pacific territories and possessions was fortified. When, therefore, the parties to that treaty agreed to maintain the fortification of certain Pacific islands in status quo, the fortification of Guam was halted. Subsequently conforming to the treaty provisions, we maintained the status quo at Guam and Corregidor, and confined our precautionary measures in the Pacific to the strengthening of Pearl Harbor and our West Coast bases. After we were no longer bound by the treaty, the proposal was made to proceed with the fortification of Guam, but after considerable debate in Congress, it was rejected.

Our foresight in developing Pearl Harbor and our West Coast bases has increased, immeasurably, our ability to carry on the war in the Pacific. Whether or not Guam could have been made sufficiently strong to withstand the full force of enemy attack is of course problematical, but we appear to have had an object lesson to the effect that if we are to have outlying possessions we must be prepared to defend them.

When, in the winter of 1935-1936, the Japanese declared themselves no longer willing to abide by existing treaty provisions or be a party to further negotiations, it gave rise to a feeling of uneasiness concerning the trend of Japanese policy and activities. Unfortunately, the full import of that move did not become apparent until later.

In 1931, Japan had embarked on a policy of aggression by the seizure of Manchuria. This was followed by other conquests in China, and as we have since learned, was accompanied by the fortifying of certain islands mandated to Japan by the League of Nations, in direct violation of the treaty provisions. A complete history of our relations with Japan during the period 1931-1941 was issued by the State Department in the so-called “White Paper” dated January 2, 1943.

Continuing her aggression, Japan moved into French Indo China in 1940. In 1941, the United States was engaged in protesting these and other moves, and while conversations with the Japanese were being held, the German offensive in Russia was being successfully pressed. It seems likely that this influenced the Japanese decision to attack Pearl Harbor.

Whatever the reasons, Japan while her representatives in Washington were still engaged in discussions, presumably with a view to finding a means of preventing war, on the morning of December 7, 1941, attacked our ships at Pearl Harbor. The attack was essentially an air raid, although there were some 45-ton submarines which participated. The primary objectives of the Japanese were clearly the heavy ships in the harbor and our grounded Army and Navy planes were destroyed in order to prevent them from impeding the attack. Damage done to the light surface forces and the industrial plant was incidental. Of the eight battleships in the harbor, the Arizona was wrecked, the Oklahoma capsized and three other battleships were so badly damaged that they were resting on bottom. The damages to the other three were comparatively minor in character. A total of 19 ships was hit, including three light cruisers which were not seriously damaged. Three destroyers were hit and badly damaged. (All three were later restored to service.) Of the 202 Navy planes ready for use on that morning only 52 were able to take the air after the raid.

Personnel casualties were in proportion to the material damage. The Navy and Marine Corps suffered a loss of 2,117 officers and men killed and 960 missing.

The Japanese losses were about 60 planes, attributable mainly to anti-aircraft fire, and it is probable that others were unable, on account of lack of fuel, to return to the carriers which composed the striking force.

A few hours later a similar but less damaging attack was made on the Philippines. (The situation in the Far East is described elsewhere in this report.)

On the following day we declared “… that a state of war which has thus been thrust upon the United States by the Imperial Government of Japan is hereby formally declared.” On December 11, a similar declaration was made concerning Germany and Italy.

II – The Wartime Navy

FIGHTING STRENGTH

Armaments

The world diplomatic situation had been deteriorating for some years, and Europe and been at war since September 1939. For those reasons, we had been adding to our fleet from time to time, beginning in 1933, but our decision to prepare ourselves fully for the inevitable conflict may be considered to have been made when the so-called Two-Ocean Navy Bill became law on July 19, 1940. At that time, we had to consider the possible disappearance of British sea power. England itself was threatened and its capture by the Germans would have meant the loss of the Royal Navy’s home bases and the industrial establishments. These, we could readily see, would become very tangible assets indeed, in the event that we were drawn into the war.

In round numbers, provision for a “two-ocean Navy” meant an expansion of about 70 per cent in our combat tonnage—the largest single building program ever undertaken by the United States or any other country.

Upon the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939, the Navy Department initiated expansion of naval shipbuilding facilities in private yards and in Navy yards. In many instances, particularly in Navy yards, the expansion provided facilities which were to be available for repairs as well as new construction.

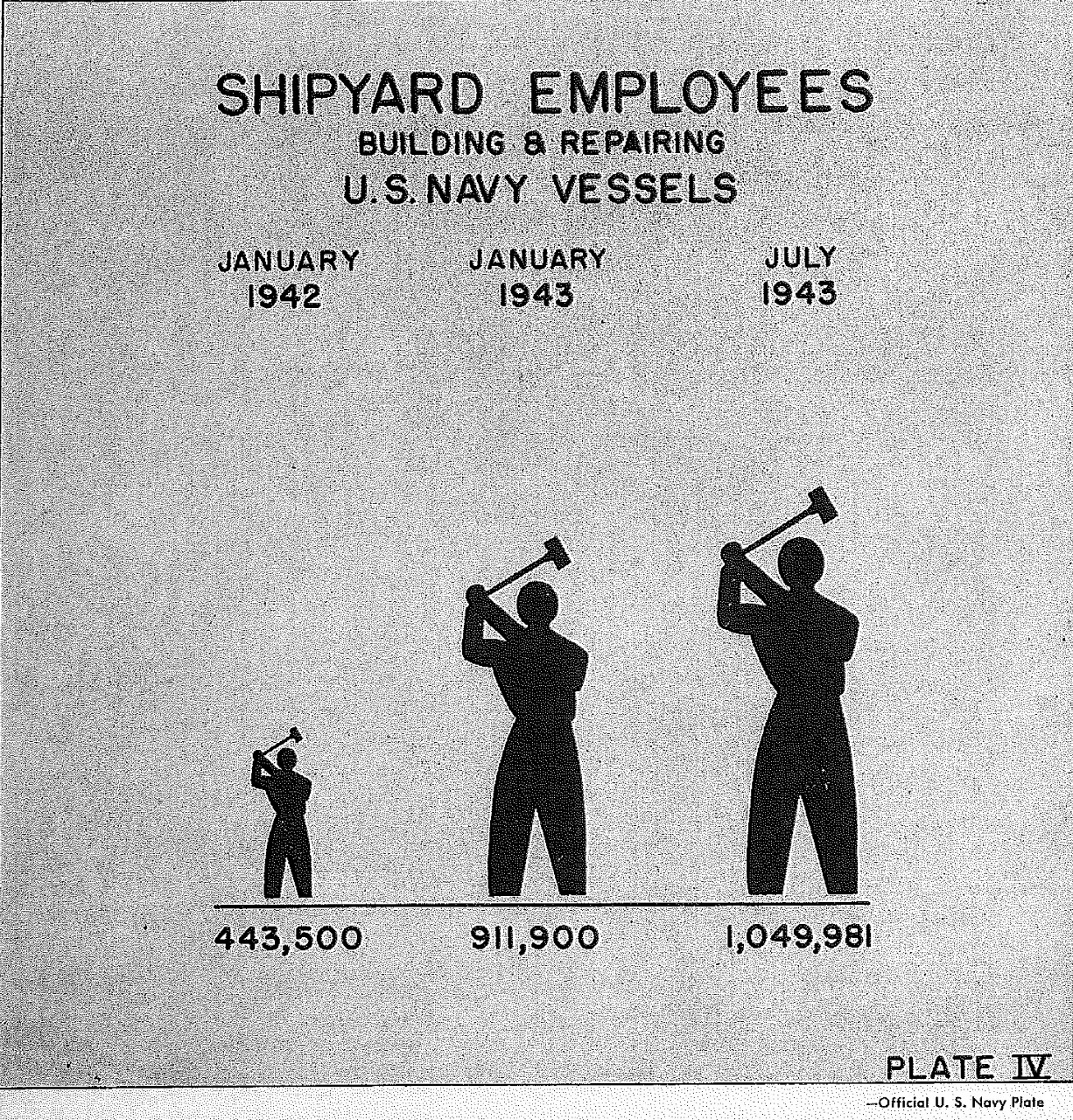

By July 19, 1940, when the two-ocean Navy was authorized, the program for expanding facilities was well started, and it continued thereafter at an accelerating rate until the early part of 1943. Early in the period of the shipyard expansion, it was apparent that as the new programs for cargo ships, tanks, planes, and Army and Navy equipment of all kinds started to pyramid, the country’s latent manufacturing capacity would soon be overloaded. Thus problem became not merely one of expanding shipyards, but of expanding the manufacturing capacity of industry as a whole to meet the needs of the Navy shipbuilding program. (See Plate 4.)

Expansion of general industry to meet the requirements of this shipbuilding program began with plants producing basic raw materials. Next to be enlarged were plants capable of manufacturing the component parts of a modern man-of-war ranging all the way from jewel bearings to huge turbines. So comprehensive was the building program that nearly every branch of American industry was affected either directly or indirectly. Manufacturers were encouraged to let out their work to subcontractors, particularly to plants which had been producing non-essential materials. An automobile manufacturer, for example, was given the job of producing

9

extremely intricate gyroscopic compasses, and a stone finishing concern undertook the manufacture of towing machines and deck winches. Early in the building program an acute situation in the construction of turboelectric propulsion machinery was solved by the construction of an enormous new plant in a 50-acre corn field. As an illustration of the speed with which the whole program was undertaken, the construction of that particular pant was not begun until May 1942, and by the end of the year the first unit had been produced, completed and shipped.

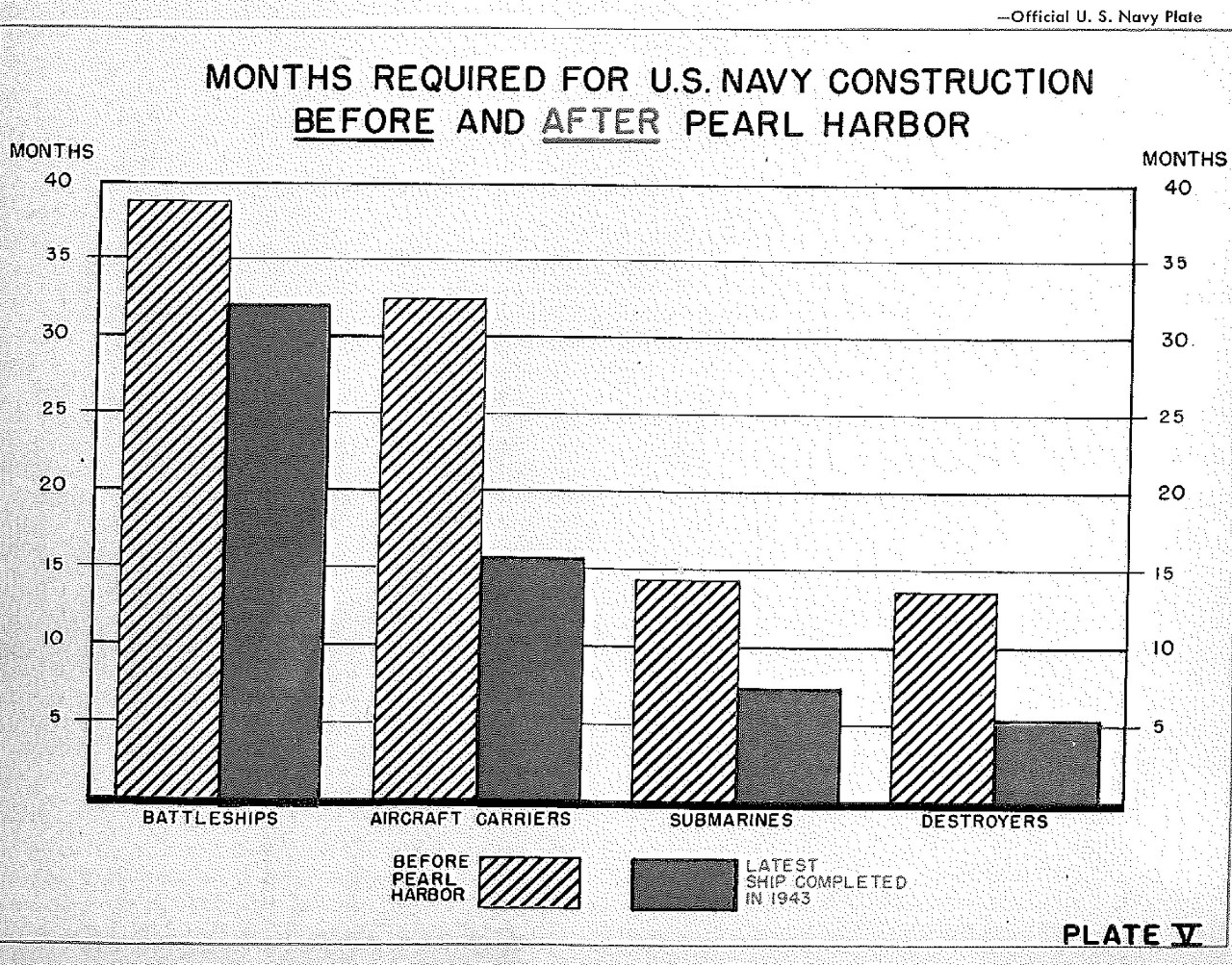

The rapidity of this naval expansion has had a profound effect upon our military strategy. As a result of it, we were enabled to seize and hold the initiative sooner than we had originally anticipated, and to deal successfully with the submarine situation in the Atlantic. The former has, of course, meant a vast improvement in our military situation everywhere, and the latter was of great benefit to the shipping situation, which was very serious in the early months of the war and threatened to become more so with the prospective increases in overseas troop movements and their support. (See Plate 5.)

Immediately after the passage of the Two-Ocean Navy Bill, corresponding contracts for new construction were let and there were soon more warships and auxiliaries on the ways than had ever been under construction anywhere in the world at any one time. Simultaneously with this new construction, the conversion of merchant ships was being accomplished, one of the most important of these being the escort carriers which later proved so effective in combatting the German submarine campaign in the Atlantic. It is interesting to note that the conversion of these ships was superimposed upon the shipbuilding effort following enactment of the Two-Ocean Navy Bill, it having been long appreciated that sea-borne aircraft would play a dominant role in overseas campaigns if and when war came.

With a construction program well under way, it was most important to keep alterations in design at a minimum in order to avoid delays. Nevertheless, changes which would increase military effectiveness or give greater protection to crews were not sacrificed for the sake of speeding up construction. Another consideration which industry had to take in its stride was the evolution of strategic plans and changes in the type of operations which made it necessary, from time to time, to shift the emphasis in construction from one type of ship to another. For example, when the war began our carrier strength was such that we could not stand much attrition. When, therefore, we suffered the loss of four of our largest aircraft carriers in the Coral Sea engagement, at Midway, and in the South Pacific, it was imperative that the construction of vessels of this category be pushed ahead at all possible speed. Shortly after we suffered the heavy loss in battleships strength at Pearl Harbor our battleships under construction at the time were given top

10

priority. At another stage of the war, when the submarine situation in the Atlantic was a matter of great concern, emphasis was placed upon escort carriers and destroyer escort vessels. At the moment, major emphasis rests with the construction of landing craft, because we intend to use them in large numbers in future operations.

The production of aircraft quite naturally assumed proportions commensurate with the building program. Thanks to the research and experimentation that had been done in improving and perfecting the various types of airplanes, and thanks also to the genius of United States industry in the field of mass production, our air power increased with almost incredible rapidity as soon as our airplane factories were expanded and retooled for the various models of planes we needed. In view of the delays to be expected from changes in design when on a mass production basis, it was apparent that a nice timing in changes of design would be necessary, so that the performance of our aircraft would always be more than a match for anything produced by the enemy. A notable example is the change-over from the Grumman Wildcat to the Grumman Hellcat.

In order to obtain a properly balanced navy the construction of combatant ships was supplemented by building patrol vessels, mine craft, landing craft and auxiliary vessels of all types. Some 55 building yards, and yacht basins, located in practically all areas of the United States served by navigable waters have participated in the patrol craft construction program.

No maritime nation has ever been able to fight a war successfully without an adequate merchant marine—something we did not have when the two-ocean Navy was authorized. The Maritime Commission therefore began a vast program of merchant ship construction at the same time we were expanding the Navy, and the merchant shipbuilding industry, too, faced an enormous expansion. Furthermore, the supply of materials necessary to complete the huge program had to be carefully allocated, in view of the country’s other needs that had to be met. The Navy needed material to build ships and manufacture planes and equipment, the Army required the material for military purposes, and civilian needs could not be neglected. In order to control the allocation of material, the War Production Board was established by the President and decisions as to priorities have since been made by that agency.

Naturally, such a great undertaking involved thousands of business transactions on the part of the Navy Department, with the contracting builders and manufacturers. These transactions have been continuous, and have been entered into on the basis of statutes which limit the profits permissible, and provide for the negotiation and renegotiation of all contracts. This part of the program has, in itself, been a colossal job.

Battleships

At the beginning of the program ten battleships were under construction. By the time Pearl Harbor was attacked only two, the North Carolina and the Washington, were in service, but since that time, six more have joined the fleet. These include the South Dakota and three sister ships, the Indiana, Massachusetts, and Alabama, and two of a larger class, the Iowa and the New Jersey. A third ship in the latter class, the Wisconsin, was launched December 7, 1943, appropriately enough, two years to the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked. In speed, in fire power, particularly antiaircraft fire, in maneuverability, and in protection, these ships represent a great advance over previous designs.

Aircraft Carriers

Construction of aircraft carriers represents one of the most spectacular phases of the naval shipbuilding program. The carrier strength of the Navy on December 7, 1941, was seven first-line vessels and one escort carrier, a converted merchant ship. Contracts had been placed for several large carries of the new Essex class, and some of these had been laid down. Conversion of a number of merchant vessels was under way. The pressing need to add to our striking power in the air and to replace losses suffered in the Pacific during 1942, led to a great expansion of the construction program for first-line carriers. Concurrently, an even larger expansion of the escort carrier program was undertaken. By the end of 1943, more than 50 carriers of all types had been put into service in our Navy, and in addition a large number of escort carriers had been transferred to Great Britain.

This remarkable record in construction enable us in a single year to build up our carrier strength from the low point reached in the autumn of 1942, when the Saratoga, the Enterprise, and the Ranger were the only ships of our fleet carrier forces remaining afloat, to a position of clear superiority in this category. The rapidity with which new carriers of various types were put into service in 1943, influenced naval operations in many important respects. Availability of several ships of the Essex class and of a considerable number of smaller carriers, completed months ahead of schedule, contributed to the success of our operations in the Southwest Pacific, aided materially in checking the submarine menace in the Atlantic, and enabled us to launch an offensive in the Central Pacific before the end of the year.

A large proportion of the Essex class carriers have joined the fleet. Excellent progress is being made on construction of the remaining ships in the original program and of the remaining ships in the original program and of the additional vessels in this class authorized after the Pearl Harbor attack. Nearly all of the carriers of the Independence class, converted from light cruisers, have been completed. These ships, though smaller than the Essex class vessels, are first-line carriers. It is planned to supplement these two basic types of carries. It is planned to supplement these two basic types of carriers with a third, substantially larger than any of our present classes, which will displace 45,000 tons, and will be capable of handling bombing planes larger than any which heretofore have operated from the decks of aircraft carriers. They will be far more heavily armed than smaller carriers and will be much less vulnerable to bomb and torpedo attack.

The Navy’s first escort carrier was the Long Island, converted early in 1941, from the merchant vessel Mormacmail. When experiments with this sip proved successful, a sizeable conversion program was initiated, using Maritime Commission C-3 hulls, and an number of oilers. In 1942, because of pressing need, this program was greatly expanded.

The “baby flat-tops” have three principal uses. They serve a anti-submarine escorts for convoys; as aircraft transports, delivering assembled aircraft to strategic areas; as combatant carriers to supplement the main air striking force of the fleet. Although their cruising speeds are lower than those of our first-line carriers, these

auxiliary carriers can be turned out more rapidly and at a fraction of the cost of conventional carriers. These ships have proved invaluable in performing convoy escort and other duties for which larger and faster carriers are not needed.

Cruisers

The Baltimore class heavy cruisers, a number of which are now in service, were designed during the period from July 19, 1940 to December 7, 1941. These cruisers are considered as powerful as any heavy cruisers afloat, particularly as recent technical developments have made it possible to improve their fighting characteristics. The Cleveland type of light cruiser (a development of the Brooklyn class) was approved for a large part of the cruiser program, its design having been completed just before the expansion was authorized. The design of the large Alaska class was the result of a series of studies commenced when treaty limitations went by the board and we were no longer bound by any limitations on the size of ships.

Destroyers and Destroyer Escorts

The Fletcher class of destroyers designed just after the outbreak of the war in Europe, formed a large part of the new destroyer building program. As compared with earlier destroyers, they are larger and have greatly increased fighting power, made possible by the same technical developments that permitted similar improvements in our cruisers.

Destroyer production has been highly satisfactory, and

12

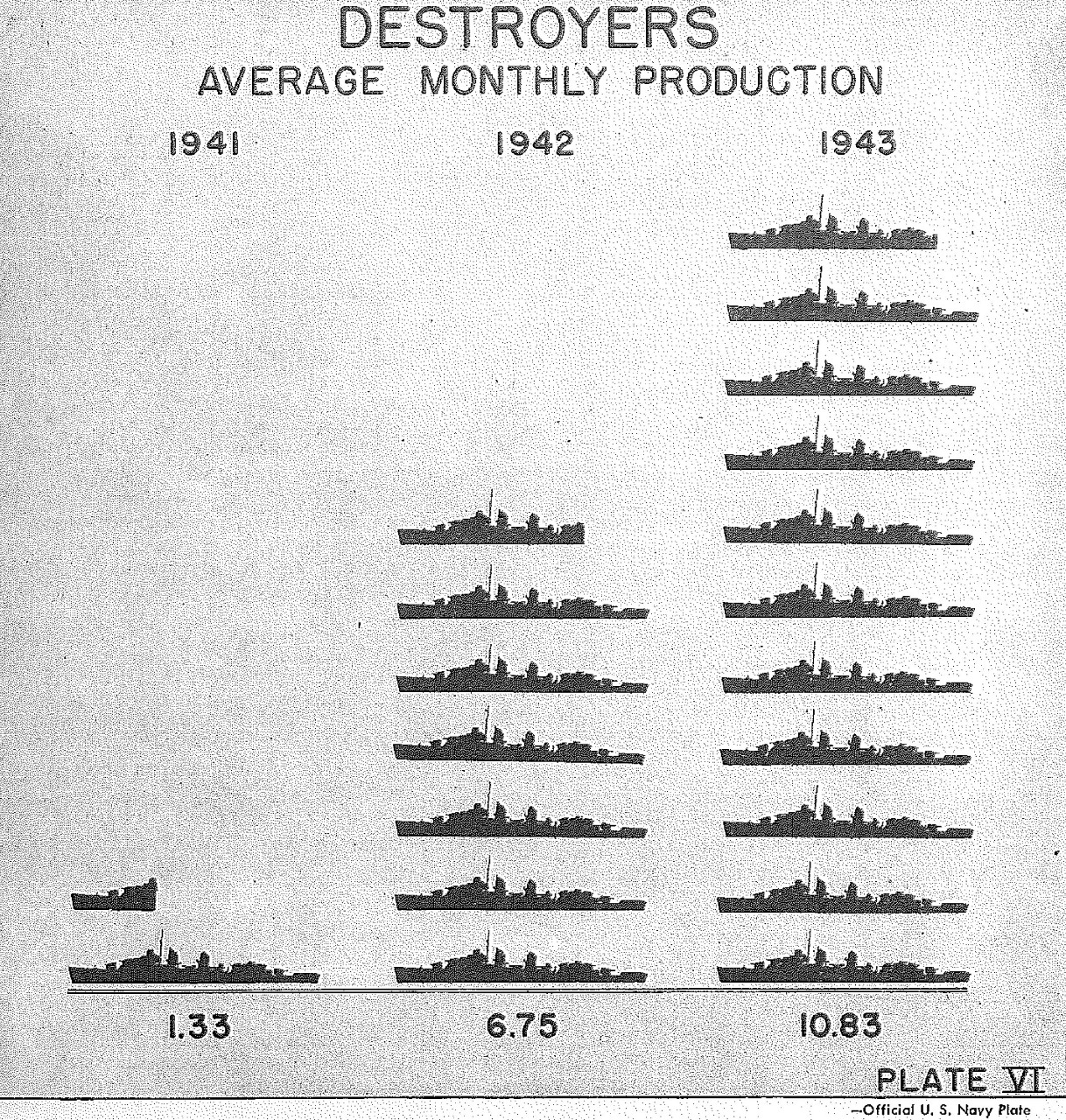

it has been possible to expand and accelerate this part of the program in an orderly manner. Although some new yards were engaged in building destroyers the increases were made possible by expanding facilities in yards which had had experience in destroyer construction. An idea of the acceleration in the rate of delivery of destroyers may be had by comparison with the figures for 1941 and 1943. In 1943, the rate was approximately eight times that of 1941. (See Plate 6.)

Contracts for the first destroyer escorts were let in November, 1941. In January 1942, the program was increased, and as Germany stepped up the construction of U-boats several more increases were found necessary. Because of priorities the commencement of a large building program was delayed, but after delivery of the first vessel of the class, in February, 1943, mass production methods became effective in the 17 building yards concerned. The result was a phenomenal output of those very useful vessels.

Submarines

As a result of the orderly progress which had been made in the construction of submarines involving continuous trial under service conditions, the main problem to be solved in building more submarines was the expansion of facilities. For a period of 15 years or more, there were only three yards in the United States with the equipment and the know-how to build submarines. These were the Navy yards at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and Mare Island, California, and the Electric Boat Company at Groton, Connecticut.

In addition to the expansion that took place at these yards, two other yards went into the production of submarines. One of these was the Cramp Shipbuilding Corporation of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the other was the Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company at Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The building at the latter yard is a further testimonial to the ingenuity displayed throughout the entire program, in that submarines are built at Manitowoc, tested in the Great Lakes, then taken through the Chicago drainage canal, and down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where they are made ready for sea.

Landing Craft

One of the most important achievements has been the landing craft construction program. Although the Navy had begun to experiment with small landing craft in 1936, we had only a few thousand tons in this category when we entered the war. In 1942, a billiondollar program for the construction of landing craft was superimposed on the already heavy building schedule, and the work was given top priority until the desired, quota was filled. The facilities of existing public and private shipyards were given part of the burden. New yards were constructed, many of them in the Mississippi Valley, where bridge-building and steel-working companies which had had no previous experience in shipbuilding put up new plants and swung into production. In the second half of 1942, almost a quarter of a million tons of landing craft were produced, and the figure increased to well over a third of a million tons for the first half of 1943.

This production included a tremendous variety of vessels from small rubber boats to tank landing ships more than 300 feet in length. Within this range are small craft designed to carry only a few men, and ships with a capacity of 200, tracked craft capable of crawling over coral reefs or up beaches, craft for landing tanks or vehicles, craft for landing guns, craft for giving close fire support—in fact, all types necessary for success in that most difficult of military operations, landing on a hostile shore.

Air planes

As a natural consequence of this importance of aviation in war, there has been a tremendous growth in the number of aircraft in the Navy.

Lessons learned in battle have been incorporated in the design of combat planes. New naval aircraft have larger engines and more power, increased protection for both crew and plane, and greater firepower than the models in service at the time of Pearl Harbor. The Grumman Wildcat, which served with distinction through the first year of the war, has been largely replaced by two new fighters—the Chance-Vought Corsair and the Grumman Hellcat. These two fighters were born of the war. While the Corsair existed as an experimental model before Pearl Harbor, it was so modified before going into production in June, 1942, and large numbers were being sent to the war fronts by the end of the year. The Corsair was followed, but in no sense succeeded by the Hellcat, which carries more armament and has greatly increased climbing ability. In production since November, 1942, and in service with the fleet since September, 1943, the Hellcat rounds out a powerful striking force for Naval aviation. These two planes are superior to anything the Japanese have.

The Douglas Dauntless scout and dive bomber, in service when this country entered the war, has undergone successive modifications but is still in use. A new plane in this category—the Curtiss Helldiver—is now ready for the fighting front. This plane can carry a greatly increased bomb load, has more firepower, and is speedier than the Dauntless.

Twelve days after the attack on Pearl Harbor the Navy approved the final experimental model of a new torpedo bomber, the Grumman Avenger. Six weeks later, this plane began coming off the production line. Undergoing its baptism of fire at the Battle of Midway, it gradually replaced the Douglas Devastator and has now become almost an all-purpose plane for the fleet. The Avenger is a speedy, strongly protected, rugged aircraft capable of delivering a torpedo attack at sea or a heavy bomb load on land targets. Since it was first put into service, its defensive armament and auxiliary equipment have been improved, and a new model introducing other improvements is almost ready for volume production.

No field of aviation has been more important to the Navy than that of long range reconnaissance and patrol. After two years of war, the Consolidated Catalina flying boat remains in active service, having proved its usefulness in performing such varied tasks as night bombing patrol, rescues, anti-submarine warfare, and even dive bombing. Since Pearl Harbor, the Catalina has been supplemented by the Marin Mariner, a larger plane, which has likewise proved to be versatile in this field.

The Navy has made increasing use of land-based patrol airplanes because of the greater speed and range of newly developed models of this type and their greater defensive ability as compared with seaplanes. With more land bases becoming available, it has been possible to

13

utilize them effectively for long over-water operations. Their superior offensive and defensive power makes them more valuable in anti-submarine warfare and for combat reconnaissance photography and patrol.

Two principal types of land-based patrol planes are now in service with the Navy—the four-engine Consolidated Liberator and the two-engine Vega Venture. The Navy’s version of the Liberator is an extremely useful plane for fast, long range reconnaissance, search and tracking. A new version, with more powerful defensive armament and greater offensive strength, soon will be available. The Ventura is a strongly armed aircraft which carries a heavy bomb load. It has proved a powerful weapon, particularly in the war against the submarine. Two other land-based bombers—the Lockheed Hudson and the Douglas Havoc—have seen limited service with the Navy, and a third—the North American Mitchell---is in use by Marine air squadrons.

The principal plane used by the Navy for scout observation work during the war, has been the Vought-Sikor-sky Kingfisher. A newer plane in this field, now in service, is the Curtiss Seagull.

The field of air transport has been enormously expanded since the beginning of the war. The Naval Air Transport Service now operates, either directly or through contract with private airlines, more than 70,000 miles of scheduled flights to all parts of the globe, helping to maintain the Navy’s long supply lines. Thus far, standard type transport planes have been used. In December 1943, however, the Martin Mars, world’s largest flying boat, was accepted by the Navy after exhaustive tests which proved its ability to carry heavy loads at long range. Manufacture of the Mars, under a prime contract with the Navy, is now under way, and the first production plane of this type recently entered actual service as cargo carriers.

Auxiliaries

The tremendous increase in the number of fighting ships and the global nature of the war required the acquisition of a commensurately large fleet of auxiliaries. These ships were obtained by construction, by conversion of standard Maritime Commission commercial hulls and by acquisition and conversion of commercial vessels. A considerable number of conversions of standard Maritime Commission types have been accomplished under the supervision of the Maritime Commission. Probably the most important vessels produced under the auxiliary program during 1943 were those which take park in actual landing operations, consisting of attack transports, attack cargo vessels and general headquarters ships. The demand for repair ships of standard and special types, which increased many-fold during 1943, was met by new construction and conversion.

Patrol Craft

As previously stated. Patrol vessels were necessary to a properly balanced Navy. The first group of patrol craft whose design was developed before the war, was completed in the spring of 1942, and more than 600 vessels of this type were completed in 1943. Motor torpedo boats (which have been employed to good advantage in several different theaters) were produced at intervals in accordance with military requirements. The classification “Patrol Craft” includes the 110-foot-sub-chaser and the 136-, 173- and 184-foot steel vessels. The greatest emphasis on this type of ship prevailed prior to and during the German, submarine offensive off our Atlantic Coast and in the Caribbean.

PERSONNEL

The expansion program and the additional requirements following the outbreak of war resulted in increases in personnel as follows. The figures given include officers and men and the Women’s Reserve, but not officer candidates or nurses:

| Sept. 8, 1939 | Dec. 7, 1941 | Dec. 31, 194 | |

| Navy | 126,418 | 325,095 | 2,252,606 |

| Marine Corps | 19,701 | 70,425 | 391,620 |

| Coast Guard | 10,079 | 25,002 | 171,518 |

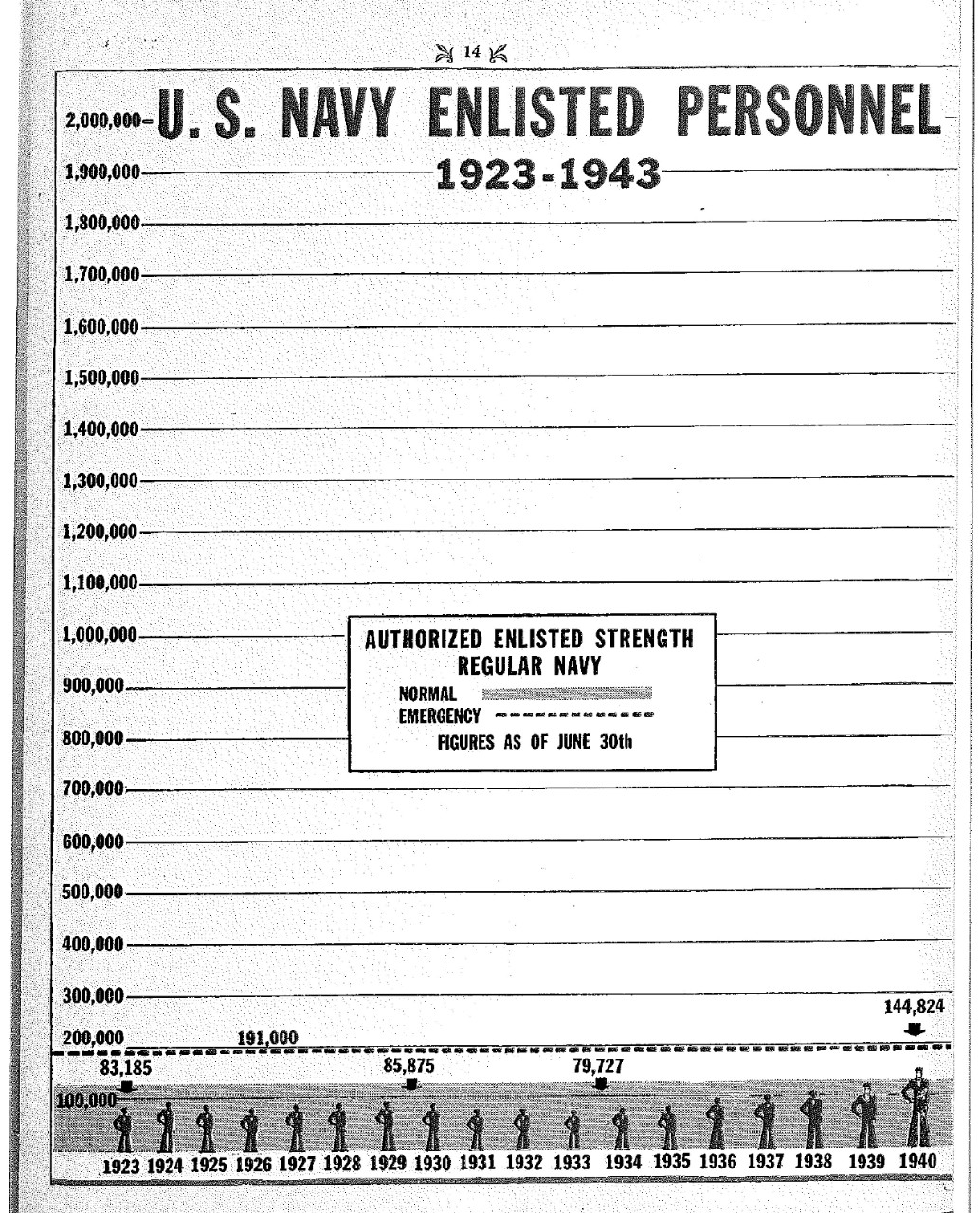

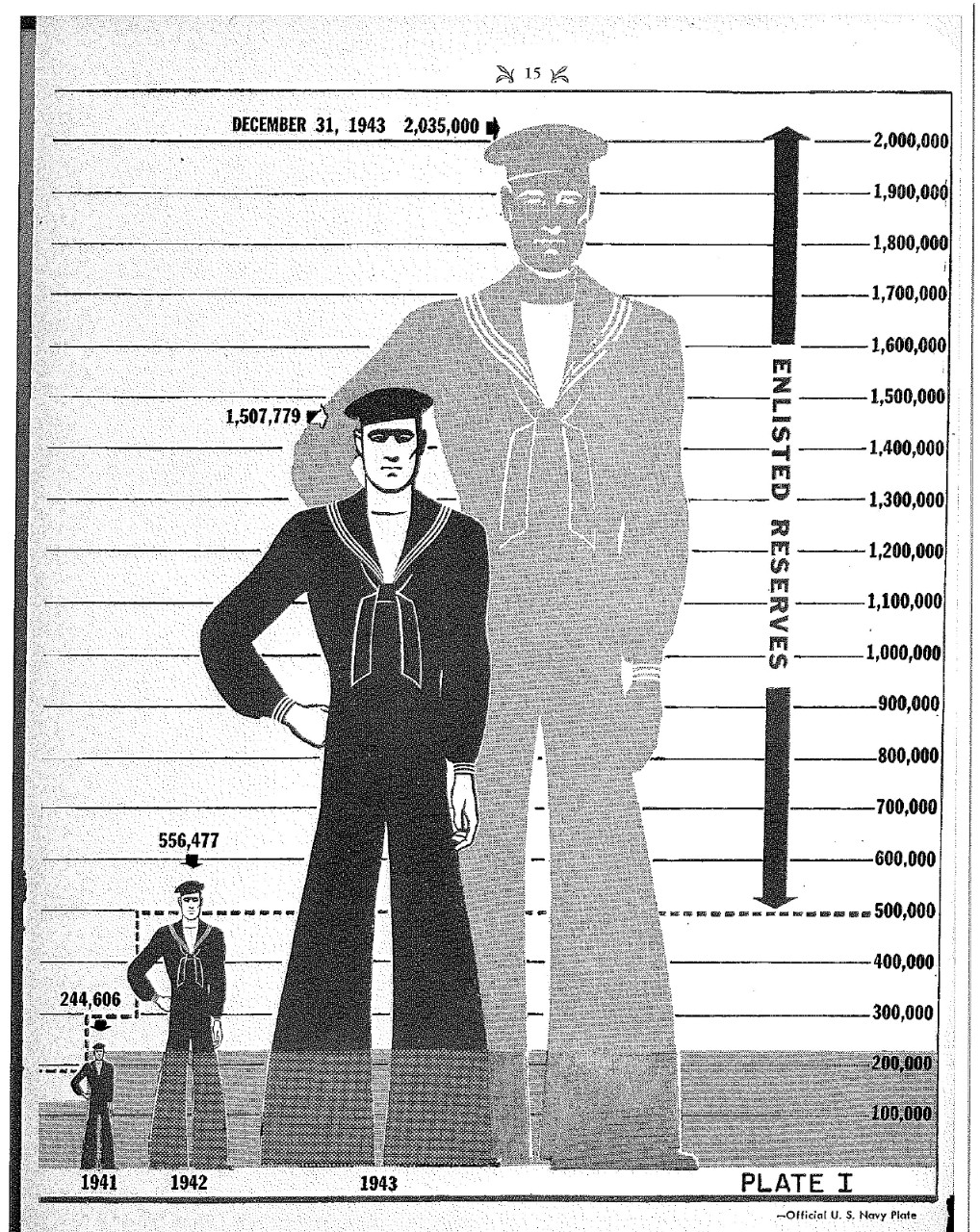

The increases in enlisted naval personnel are shown graphically on the accompanying chart. (See Plate I.)

Taking the number of men indicated into an organization was in itself an enormous undertaking. Training them was an even greater undertaking. Training them was an even greater undertaking, in spite of their high intelligence and the other characteristics which make the American fighting man the equal of any in the world.

Procurement of Officers

In time of peace the Navy is manned almost entirely by officers of the regular Navy, most of whom are graduates of the Naval Academy. Several years before the war, knowing that the Naval Academy would not be able to supply officers in sufficient quantities for wartime needs, the Navy established Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps units at various colleges throughout the country. Under the system set up, students were given the opportunity to take courses in naval science (which included training at sea during the summer months) and upon successfully completing them, were commissioned in the Naval reserve. When the limited emergency was declared, these officers were ordered to active duty, but when the war broke out it became apparent that the combined supply of commissioned officers from the Naval Academy and from ROTC units would not be sufficient to meet our needs for the rapidly expanding Navy.

In February, 1942, therefore, offices of naval officer procurement were established in key cities throughout the country. Hundreds of thousands of officer candidates went to these offices and there presented their qualifications. With the requirements of health, character, personality and education duly considered, the applications of those who appeared qualified were forwarded to the Navy Department for final consideration. Under this procedure some 72,000 officers were commissioned in the Navy Directly from civil life, to meet immediate needs.

Meanwhile, educational programs designed to produce commissioned officers had been established in numerous colleges throughout the counry. Included were the aviation cadet program (V-5) principally for physically qualified high school graduates and college students, and later the Navy college program (V-12) which absorbed under-graduate students of the accredited college program (V-1), and of the reserve midshipman program (V-7). At the present time there are 66,815 members of the V-12 program in some 241 different colleges.

From the foregoing, it will be seen that high school graduates are ow the Navy’s principal source of young officers. Their training is described elsewhere in this

16

report, but the various programs for naval reserve officers have supplied the fleet with large numbers, many of whom have already demonstrated their ability and the wisdom of the policy calling for their indoctrination and training before being sent to sea. Officers of the regular Navy are universally enthusiastic over the caliber of young reserve officers on duty in the fleet.

In general, procurement of officers has kept up with the needs of the service, with the exception of officers in the medical, dental, and chaplain corps and in certain highly specialized fields of engineering. As graduates of professional schools are the chief source of commissioned officers in the various staff corps and as there must be a balance between military and civilian needs, we are at present somewhat short of our commissioned requirements in certain branches of the service.

By comparison with the increase in size of the naval reserve, the increases in the regular Navy have been small. The output of the Navy Academy is at is peak, however, having been stepped up by shortening the course to three years and by increasing the number of appointments. In addition, during 1943, 20,652 officers have been made by the advancement of outstanding enlisted personnel.

Recruiting of Enlisted Personnel

When the President declared to the existence of a limited emergency on September 8, 1939, the personnel strength of the Navy had been increased by calling retired officers and men to active duty and by giving active duty status to members of the naval reserve who volunteered for it. At the time the large naval expansion was authorized in July 1940, however, there were still only slightly more than 160,000 men in the Navy and by the end of that year only 215,000. As late as June, 1941, the total was still well below 300,000 and it was apparent that a radical increase over and above the existing figure was an immediate necessity. Various measures were therefore taken to stimulate recruiting, by virtue of which the Navy strength stood at 290,000 on December 7, 1941. In other words, we doubled our personnel in two years.

Immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor there was a large increase in enlistments, and by the end of that month some 40,000 additional men had been accepted for naval service. This heavy enlistment rate, however, experienced in December, 1941, and January, 1942, subsequently fell off at a time when the requirements were still mounting. In order to meet the situation and to provide an adequate method of recruiting the large numbers of men needed, our recruiting system, which had already been expanded, was fortified by a field force of officers commissioned directly from civil life, and by the fall of 1942, we were accepting each month a total equivalent to peacetime Navy Strength.

On December 5, 1942, the voluntary enlistment of men between the ages of 18 and 37, inclusive, was ordered terminated as of February 1, 1943, on which latter date the manpower requirements of the Navy were supplied by operation of the machinery of the Selective Service system. During the period of active recruiting about 900,000 volunteers were accepted. Since February 1, 1943, 779,713 men have entered the Navy through Selective Service. During the same period voluntary enlistments within the age limits prescribed totaled 205, 669.

On June 1, 1943, the Army and Navy agreed on joint physical standards which were somewhat lower than those previously followed by the Navy, but still sufficiently rigid to permit all inductee to be assigned to any type of duty afloat or ashore.

Training

Strictly speaking, it is probably true that training is a continuous process, which begins when an individual enters the Navy and ends when he leaves it. In time of peace the number of trained men in the Navy is relatively high. In time of war, however, particularly when we experience a personal expansion such as has been described, trained men are at a premium. It is not an exaggeration to state that our success in this war will be in direct proportion to the state of training of our own forces.

When we entered the war we experienced a dilution in trained men in new ships because of the urgency of keeping trained men where fighting was in progress, and initial delays in getting underway with the huge expansion and training program had to be accepted. As the war progressed, and as the enemy offensive was checked, we were able to assigned larger numbers of our trained men to train other men. Our ability to expand and train during active operations reflects the soundness of our peacetime training and organization. With that as a foundation on which to build, and with the tempo of all training stepped up, adequate facilities, standardized curricula, proper channeling of aptitude, full use of previous related knowledge, lucid instructions, and top physical condition became the criteria for wartime training.

Generally speaking, the first stage in the training of any new member of the Navy is to teach him what every member of the Navy must know, such as his relationship with others, the wearing of the uniform, the customs of the service, and how to take care of himself on board ship. The second stage involves his being taught specialty and being thoroughly grounded in the fundamentals of that specialty. The third stage is to fit him into the organization and teach him to use his ability to the best advantage.

Commissioned Personnel

The over-all problem of training officers involves a great deal more than the education of the individual in the ways of the Navy. The first step is classification according to ability, which must be followed by appropriate assignment to duty. This is particularly true in the case of service officers, who must be essentially specialists, because there is insufficient time to devote to the necessary education and training to make them qualified for detail to more than one type of duty.

As previously stated, ROTC units, which were part of the V-1 training program, had been established in various colleges, and courses in naval science, which included drills and summer cruises, were worked into the academic careers of the individuals enrolled. With the approach o war, the training of these students was shortened in most colleges to two and one-half years, and eventually they became part of the Navy college training program (V-12).

In 1935, the Congress authorized the training of Naval aviation cadets, and that statutory authority was implemented by a program for their training, known as the V-5 program, which was open to physically qualified high school graduates and college students. Under the methods adopted, a decision as to whether or not a candidate would be accepted for the V-5 program was made by Naval Aviation Cadet Selection Boards, who were

17

guided by high standards covering the educational, moral, physical and psychological qualifications of each individual. The period of training normally requires from 12 to 15 months, exclusive of additional college training required to for 17 year old students. Of this time, six to eight months are spent in preliminary raining in physical education and ground school subjects at pre-flight schools. The remainder of the training consists of primary, intermediate and advanced flight training. Upon successful completion of the full flight training course, an aviation cadet is commissioned ensign in the Naval Reserve or second lieutenant in the Marine Corps Reserve and is then ordered to active duty as a pilot.

The V-12 (Navy college training) program was established on July 1, 1943. It consisted initially of students who were on inactive duty in the Naval Reserve, new students from civilian life, and young enlisted men especially selected. The new students from civilian life consist of selected high school graduates or others with satisfactory educational qualifications who can establish by appropriate examination their mental, physical and potential officer qualifications. These students are then inducted, into the Navy as apprentice seamen or as privates, United States Marine Corps, placed on active duty, and assigned to designated colleges and universities to follow courses of study specified by the Navy Department.

V-12 training embodies most of the features of preceding Naval Reserve programs. Depending on training dental officers, engineering specialists, and chaplains, length of courses vary from two to six semesters. The courses of study include fundamental college work in mathematics, science, English, history, naval organization and general naval indoctrination for the first two terms for all students. This is followed by specialized training being based upon his choice and upon his demonstrated competence in the field chosen, subject to available quotas. Upon satisfactory completion of college training, students are assigned to further training in the Navy, Marine Corps or Coast Guard, and if found qualified after completion of that training they are commissioned in the appropriate reserve.

So far, the V-12 program has worked well. It permits the selection of the country’s best qualified young men on a broad democratic basis without regard for financial resources, and the induction and training of those young men who show the greatest promise of having superior ability and the other qualities likely to make a good officer.

The link between the College Training Program and the fleets is the Naval Reserve Midshipman Program. The Navy college graduates who are going to deck and engineering duties with the forces afloat are sent to one of the six reserve midshipman schools for a four months’ course. Upon the successful completion of the first month’s study, they are appointed reserve midshipmen, and after the remaining three months’ intensive training, they are appointed ensigns in the Naval Reserve.

Originally four reserve midshipman schools were established, located at Columbia University, Northwestern University, Notre Dame, and the Naval Academy. The program has been such an outstanding success, and the demand for its graduates has so increased, that two additional schools recently have been put into commission, at Cornell and at Plattsburg, New York, with the result that there are nearly 9,000 men in this training program at any one time. The combined result of the College Training Program and the Reserve Midshipman Program is to meet the need of the fleets for thoroughly trained young deck and engineering officers.

Enlisted Personnel

Recruit training in addition to the instruction given the individual in the ways of the Navy, consists of his being fully informed of the training opportunities open t him. This is followed by a series of tests designed to determine the ability of each recruit. These tests are based on the type of duty to be performed in the Navy, and in addition to such tests as the general classification test, consists of a systematic determination of aptitudes in reading and mechanical ability and any knowledge of specific work. Through a system of personal interviews these tests are supplemented by considering the background and experience of the individual, so that the special qualifications of each recruit may be evaluated. This information is then indexed and recorded and used in establishing quotas for the detail of men to special service schools or to any other duty for which they seem best qualified.

While the recruit is learning about the Navy, therefore, the Navy is learning about him. A practical application of this system was the assembly of the crew for the USS New Jersey, a new battleship. While the ship was fitting out, a series of tests and a thorough study of the requirements of each job on board were conducted. For example, special tests determined those best fitted to be telephone talkers or night lookouts or gun captains, and as a result, when the crew went aboard each man was assigned to a billet in keeping with his aptitude for it.

As permanent establishments, we had four training stations—Newport, Rhode Island; Norfolk, Virginia; Great Lakes, Illinois, and San Diego, California. As soon as we entered the war it became apparent that it would be necessary to expand these four stations radically and to establish others. By November 1942, we had expanded the four permanent training stations and established new ones at Bainbridge, Maryland; Sampson, New York, and Farragut, Idaho.

The training in the fundamentals of the specialty to be followed by a newcomer to the Navy is carried on ashore and afloat. Recruits showing the most aptitude for a particular duty are sent to special service schools designed to give the individual a thorough grounding in his specialty before assuming duties on board ship. If he hopes to become an electrician’s mate he may be assigned to the electrical school, if a machinist’s mate, to the machinist’s mate school, if a machinist’s mate, to the machinist’s mate school, if a commissary steward, to the cook’s and baker’s school, and so forth. Approximately 32 per cent of those who received recruit training are assigned to special service schools.

An advanced type of training is given men who are already skilled in a specialty by assembling them and training them to work as a unit. This is known s operational training, and in addition to the special meaning of the term as applied to aviation training, it encompasses such special activities as bomb disposal units as well as the training of ship’s crews before the ship is commissioned.

When the individual goes on board ship, he discovers that his training has only begun, because he must learn how to apply the knowledge he has already gained and

18

how his performance of duty fits into the organization of the ship. This is another form of operational training—conducted, of course, by the forces afloat—which is a preliminary to the assignment of that ship as a unit of the fleet. This does not mean that the ship is fully trained, but it means that the ship is fully trained, but it means that the training is sufficiently advanced to fit the crew for the additional training and seasoning that comes only with wartime operations at sea. With the proper background of training, the most efficient ship is very likely to be the one which has been in action. In other words, actual combat is probably the best training of all, provided the ship is ready for it.

HEALTH

The health of the personnel in our naval forces has been uniformly excellent. In addition, the treatment and prevention of battle casualties has become progressively better.

The Medical Corps of the Navy has not only kept up with scientific developments everywhere, but it has taken the lead in many fields. The use of sulfa drugs, blood plasma and penicillin, plus the treatment of war neuroses probably represent the outstanding medical accomplishments of the war, but all activities requiring medical attention have been under continuous study.

For example, the conditions under which submarines must operate have been found to require special diet, air conditioning, sun lamps, special attention to heat fatigue, and careful selection of personnel. Similarly, in the field of aviation medicine, flight surgeons, who are themselves qualified naval aviators and therefore familiar with all aviation problems, have been instrumental in keeping our aviation personnel at the peak of their efficiency.

Naval mobile hospitals were developed shortly before the war. These are complete units, capable of handling any situation requiring medical attention. Each unit contains officers of the Medical Corps, the Dental Corps, the Hospital Corps, the Nurse Corps, the Supply Corps, the Civil Engineer Corps and the Chaplain Corps, and in addition, enlisted personnel of a wide variety of non-medical ratings such as electricians, cooks, and bakers. Mobile hospitals are organized and commissioned, and being mobile as the name implies, are placed under the orders of the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, for such duty as may be deemed desirable, the same as a ship. These mobile hospitals have proved invaluable in all theaters.

While it is hardly possible to single out any one activity as outstanding, the practice of evacuating sick and wounded personnel from forward areas by plane to be treated elsewhere, has been estimated to have increased the efficiency of treatment by about one-third. The beneficial effects of this practice on our ability to carry on a prolonged campaign, such as in the Solomon Islands, are obvious.

There have been many more contributions to our military efficiency having to do with not only medicine, but health in general. The question of malaria control in the Solomon Islands, protective clothing, survival od personnel in lifeboats, the purification of drinking water, the treatment of flash burns, the recording by tag of first aid treatment received in the field, and periodic thorough physical examination are a dew of the progressive measures which, collectively, have been responsible for marked increases in our military efficiency.

The Marine Corps

Statistics previously given indicate the personnel expansion of the Marine Corps. In terms of combat units those figures represent a ground combat strength of two half-strength divisions and seven defense battalions expanded to five divisions, 19 defense battalions and numerous force and Corps troop organizations and service units; 12 aviation squadrons expanded to 85; and increases in ships’ detachments to keep pace with the ship construction program. Under the leadership of Lieutenant General T.H. Holcomb, U.S.M.C., the Marine Corps successfully met the greatest test in its history by forging a huge mass of untrained officers and men into efficient tactical units especially organized, equipped, and trained for the complicated amphibious operations which have characterized the war in the Pacific.

Training of the expanding Marine Corps personnel had to be conducted by stages because existing bases were inadequate in housing, space, and facilities. Basic training for all Marines was continued at the established recruit depots at Parris Island, South Carolina, and San Diego, California. Specialized advanced training for ground and aviation personnel before being assigned to combat units was conducted chiefly at Camp Lejeune, New River, North Carolina; at Camp Elliott, near San Diego, California; and at Camp Pendleton, Oceanside, California. Improvised facilities were used at those three bases until they had been developed into centers capable of affording training in all the basic and special techniques required in amphibious warfare. The final stage of training began with assignment of personnel to combat units and ended with the movement of those units to combat areas. (The effectiveness of individual and unit training of the Marine Corps was first demonstrated at Guadalcanal and Tulagi, eight months after the beginning of the war. That first test showed Marine Corps training methods to be sound and capable of producing combat units in a minimum of time.)

The commissioned personnel of the expanding Marine Corps were initially obtained from reservists and graduates of the Marine Corps Schools at Quantico. Later, commissioned personnel were obtained by including the Marine Corps in the Navy V-12 program, by selecting candidates from graduates of designated colleges and universities, and by increasing the number of enlisted men promoted to commissioned rank.

Marine Corps aviation, while expanding to a greater degree than the Corps as a whole, has continued to specialize in the providing of air support to troops in landing or subsequent ground operations. Training and organization in the United States and excellent equipment have made it possible to operate planes from hastily constructed airfields with limited facilities. The generally excellent performance of Marine aviation squadrons operating from forward bases in the Central and South Pacific areas in successful attacks against enemy aircraft, men-of-war, and shipping, attests the soundness of the organization.

In November 1942, the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve was established, the authorized strength being 1,000 commissioned and 18,000 enlisted women, to be reached by June 30, 1944. By December 31, 1943, there

19

were 609 officers and 12,592 enlisted women in the organization, all of whom have released male Marines for service in combat areas. The remarks relating to the performance of duty of the Waves, contained in that part of this report covering their organization and training, are equally applicable to women in the Marine Corps.

Participation of Marines in combat is covered in Part 111 of this report.

The Coast Guard

The duties of the Coast Guard under Naval administration consist of the civil functions normally performed by the Coast Guard in time of peace which become military functions in time of war, and the performance of Naval duties for which the personnel of the Coast Guard are particularly fitted by reason of their peacetime employment. The organization operates separately with respect to appropriations, required for Coast Guard vessels, shore stations, and personnel.

The increase in the size of the Coast Guard was necessitated chiefly by additional duties in connection with captain-of-the-port activities in the regulation of merchant shipping, the supervision of the loading of explosives, and the protection of shipping, harbors, and water front facilities. In addition, the complements of Coast Guard vessels and shore establishments were brought up to wartime strength, certain transports and other naval craft, including landing barges, were manned by Coast Guard personnel, and a beach patrol (both mounted and afoot) and coastal lookout stations were established. The Coast Guard also undertook the manning and operating of Navy section bases and certain inshore patrol activities formerly manned by naval personnel, and furnished sentries and sentry dogs for guard duty at various naval shore establishments.

Coast Guard aviation, which is about three times its previous size, has been under the operational control of Sea Frontier Commanders, for convoy coverage, and for anti-submarine patrol and rescue duties. Other squadrons outside of the United States are employed in ice observation and air-sea rescue duty. Miscellaneous duties assigned to Coast Guard aviation include aerial mapping and checking for the Coast and Geodetic Survey and ice observation assistance on the Great Lakes.

The assignment of certain Coast Guard personnel to duties radically different from those they normally perform required numerous changes in ratings. This resulted in extensive classification and retraining programs designed to prepare men for their new duties. The replacement of men on shore jobs by Spars, both officer and enlisted, has been undertaken as a part of this retraining program. Approximately 10,000 Spars—whose performance of duty and value to the service is on a par with that of the Waves and the women of the Marine Corps—will be commissioned and enlisted when the contemplated strength of that organization is reached.

The present strength of the Coast Guard was attained by the establishment of the Coast Guard Reserve and by commissioning warrant officers and enlisted men for temporary service. Other increases in the commissioned personnel of the Coast Guard have been accomplished by appointments made direct from civil life in the case of individuals with particular qualifications, such as special knowledge in the prevention and control of fires, police protection and merchant marine inspection.

A feature peculiar to the Coast Guard is the Temporary Reserve, which consists of officers and enlisted men enrolled to serve without pay. Members of the Temporary Reserve have full military status while engaged in the performance of such duties as pilotage, port security, the guarding of industrial plants, either on a full or part-time basis. At the present time there are about 70,000 members of the Temporary Reserve, but it is anticipated that it will eventually be reduced to about 50,000. The Coast Guard Auxiliary, which is a civilian organization, has contributed much of its manpower to the Temporary Reserve, the result being a substantial saving in manpower to the military services.

Under the general direction of Vice Admiral R.R. Waesche, U.S.C.G., Commandant, the Coast Guard has done an excellent job in all respects, and as a component part of the Navy in time of war, has demonstrated and efficiency and flexibility which has been invaluable in the solution of the multiplicity of problems assigned. The organization and handling of local defense in the early days of the war were particularly noteworthy.

The Seabees

For some months before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor we had been strengthening our insular outposts in the Pacific by construction of various construction companies were subjected to attack, along with our garrisons of Marines.

In that situation, the civilians were powerless to aid the military forces present because they lacked the weapons and the knowledge of how to use them. Furthermore, they lacked what little protection a military uniform might have given them. As a consequence, the Navy Department decided to establish and organize Naval construction battalions whose members would be not only skilled construction workers but trained fighters as well.

On December 28, 1941, authorization was obtained for the first contingent of “Seabees” (the name taken from the words “Construction Battalions”) and a recruiting campaign was begun. The response was immediate, and experienced men representing about 60 different trades were enlisted in the Navy and given ratings appropriate to the degree and type of their civilian training.

After being enlisted these men were sent to training centers where they were given an intensive course in military training, toughened physically, and in general educated in the ways of the service. Particular attention was paid to their possible employment in amphibious operations. Following their initial training, the Seabees were formed into battalions, so organized that each could operate as a self-sustained unit and undertake any kind of base building assignment. They were sent to advance base depots for outfitting and for additional training before being sent overseas.

The accomplishments of the Seabees have been one of the outstanding features of the war. In the Pacific, where the distances are great and the expeditious construction of bases is frequently of vital importance, the construction accomplished by the Seabees has been of invaluable assistance. Furthermore, the Seabees have participated in practically every amphibious operation undertaken thus far, landing with the first waves of assault troops

20

to bring equipment ashore and set up temporary bases of operation.

In the Solomon Islands campaign, the Seabees demonstrated their ability to outbuild the Japs and to repair airfields and build new bases, regardless of conditions of weather. Other specialized services performed by the Seabees include the handling of pontoon gear, the repair of motor vehicles, loading and unloading of cargo vessels, and in fact every kind of construction job that has to be done.