The Navy Department Library

Northern Barrage and Other Mining Activities

PDF Version [15.5MB]

NAVY DEPARTMENT

OFFICE OF NAVAL RECORDS AND LIBRARY

HISTORICAL SECTION

Publication Number 2

THE NORTHERN BARRAGE AND OTHER MINING ACTIVITIES

Published under the direction of

The Hon. JOSEPHUS DANIELS, Secretary of the Navy

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

1920

THE NORTHERN BARRAGE AND OTHER MINING ACTIVITIES.

ERRATA

Page 125, after paragraph 2 add: The following submarines were sunk in the Northern Mine Barrage:

| Area | Submarine | Date |

| B | U-92 | September 9, 1918 |

| B | U-102 | September — (Probable) |

| A | U-156 | September 25, 1918 |

| B | UB-104 | September 19, 1913 |

| B | UB-127 | September — (Probable) |

| A | UB-123 | October 19, 1918 |

Sources: The Submarine Warfare by Micholson and British Submarine Losses Return 1919.

Page 124, paragraph 3, 1st line: change last word to one. 5th line: strike out sentence beginning "The other, the UB-22, etc."

Page 125, paragraph 1, 4th line: change U-123 to read UB-123.

THE NORTHERN BARRAGE AND OTHER MINING ACTIVITIES.

Publication No. 2, Historical Section, Navy Department.

ERRATA.

Page 48, line 14: After the word “dimensions” strike out “34” and insert 33.

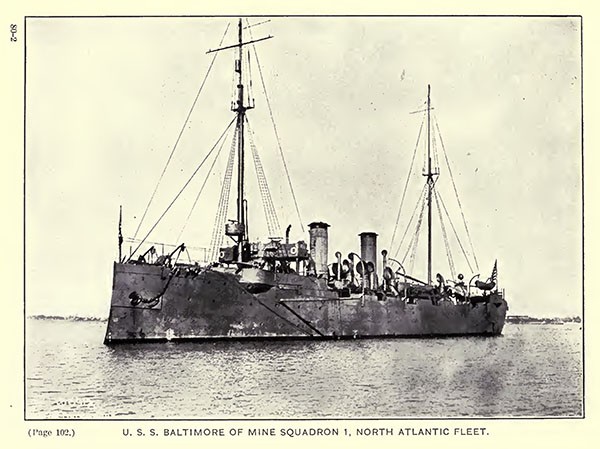

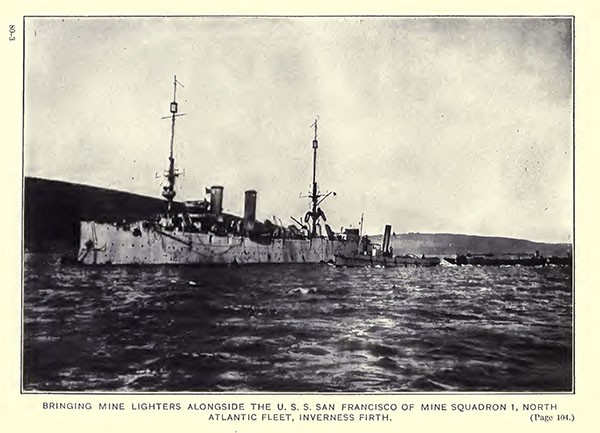

Facing page 80, photographs: In captions for photographs of U. S. S. Baltimore and U. S. S. San Francisco, strike out “North Atlantic Fleet” and insert U. S. Mine Force.

Page 87, line 8: After the word “miles” insert the word in.

Page 105, line 4: Strike out the word “proceed” and insert the word proceeded.

Page 140, line 43: Strike out the word “has,” and after the word “issued” insert (Up to July 18, 1919).

Note: These Mine Warnings to Mariners are still being issued. Up to February 3, 1921, 413 have been received by the Hydrographic Office of the Navy Department.

Page 141, line 2: After the word “date” insert period.

Page 141, lines 2, 3, and 4: Strike out the words “and are published herewith in explanation of the policy that was to be carried out" and insert in lieu thereof The explanation of the policy to be carried out is illustrated in the two charts of a later date which accompany this publication.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Page. | |

| List of illustrations | 5 |

| Preface | 7 |

| Chapter I. | |

| The conception and inception of the northern barrage project | 9 |

| Chapter II. | |

| British consideration of project | 29 |

| Chapter III. | |

| American consideration and adoption of project | 35 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| Status of barrage project on November 1, 1917 | 38 |

| Chapter V. | |

| Coordination of preparations | 40 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| Design of the mine | 42 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| The manufacturing project | 50 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| Mine loading plant, St. Juliens Creek, Va | 55 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| Assembly and shipment of mine material | 58 |

| Chapter X. | |

| Overseas mine bases Nos. 17 and 18 | 61 |

| Chapter XI. | |

| Organization of mine squadron and selection of new minelayers | 70 |

| Chapter XII. | |

| Training the personnel and commissioning the ships of Mine Squadron One. | 76 |

| Chapter XIII. | |

| Completion and sailing of mine squadron | 79 |

--3--

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| Chapter XIV. | |

| Page. | |

| Commander Mine Force—Appointment, arrival in Europe, preparations for commencement of minelaying | 86 |

| Chapter XV. | |

| Changes in barrage plan | 92 |

| Chapter XVI. | |

| Mining operations | 101 |

| Chapter XVII. | |

| Final status of barrage and results obtained | 121 |

| Chapter XVIII. | |

| Contemplated mining operations in the Mediterranean | 128 |

| Charts in Pocket. | |

| No. 1. Chart of waters surrounding British Islands. Mined areas and safe channels. 2. Chart of Mediterranean with west coasts of France, Spain, and Portugal. Mined areas and safe channels. |

|

--4--

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss, U. S. Navy, commander of the American mining operations in the North Sea, during the World War | Frontispiece. |

| Facing page— | |

| Admiral Henry T. Mayo, U. S. Navy, commander in chief, U. S. Atlantic Fleet, and Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss | 16 |

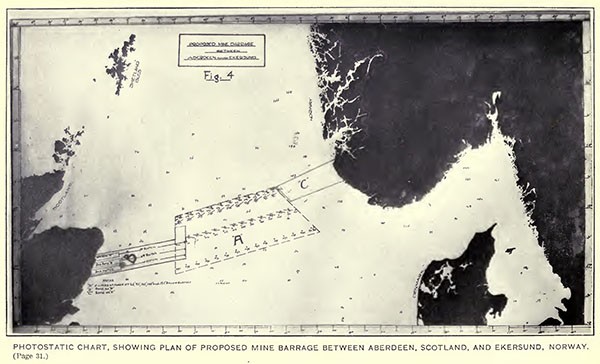

| Photostatic chart, showing plan of proposed mine barrage between Aberdeen, Scotland, and Ekersund, Norway | 16 |

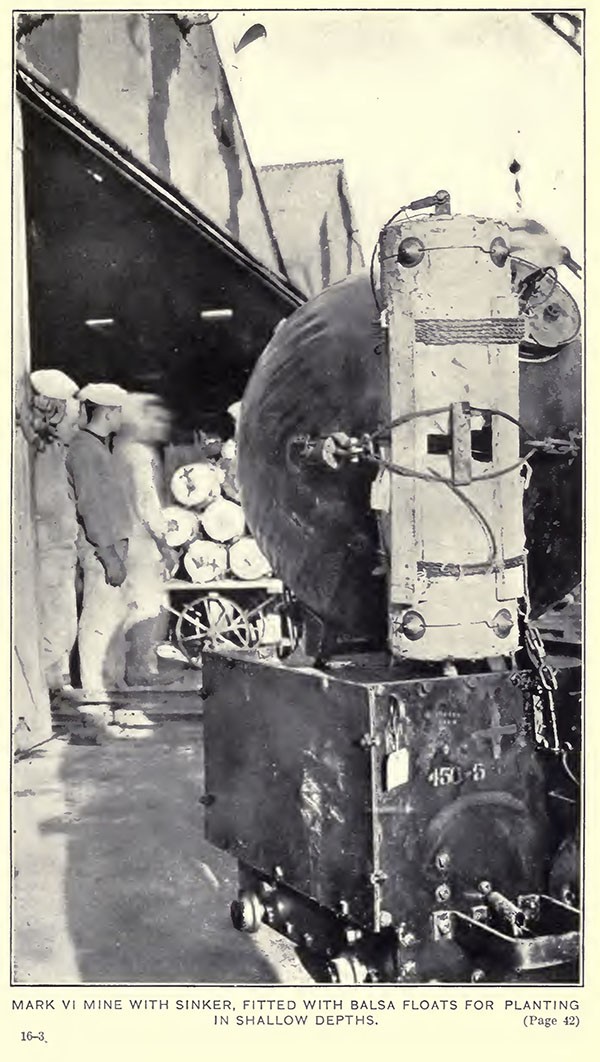

| Mark VI mine with sinker, fitted with balsa floats for planting in shallow depths. | 16 |

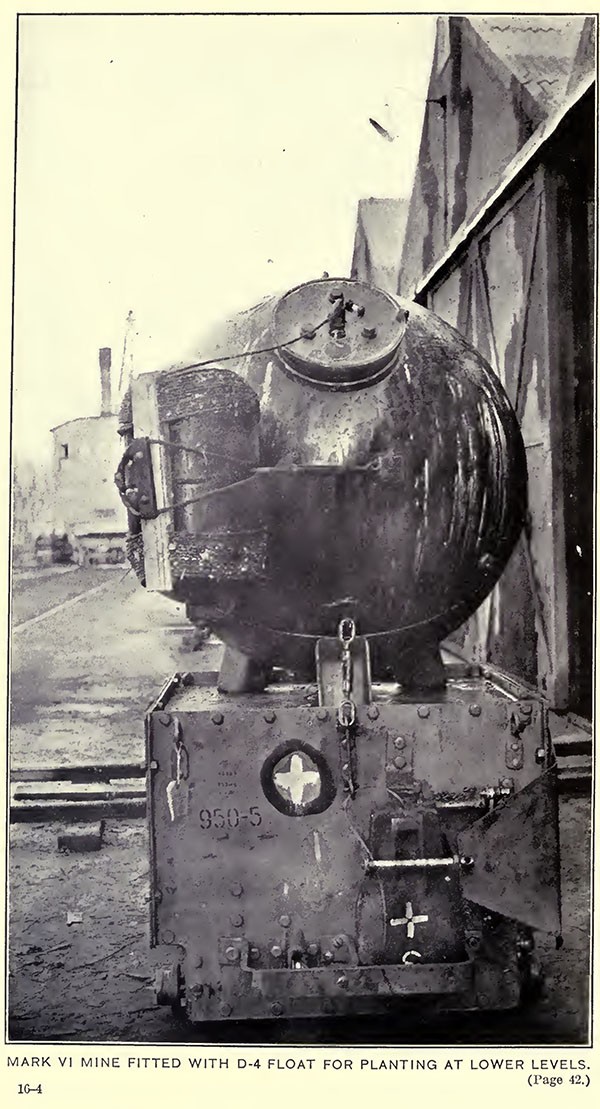

| Mark VI mine fitted with D-4 float for planting at lower levels | 16 |

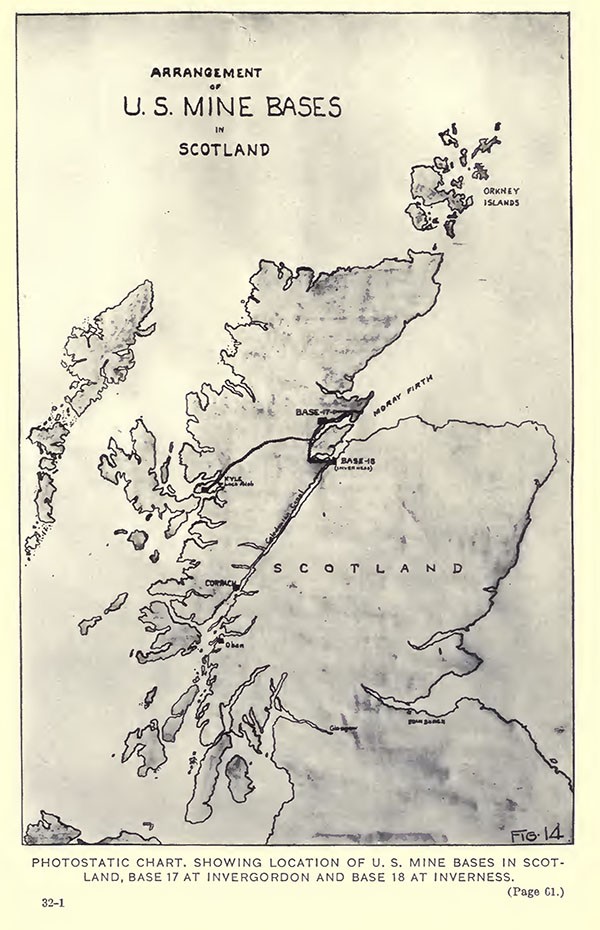

| Photostatic chart, showing location of U. S. Mine Bases in Scotland, Base 17 at Invergordon and Base 18 at Inverness | 32 |

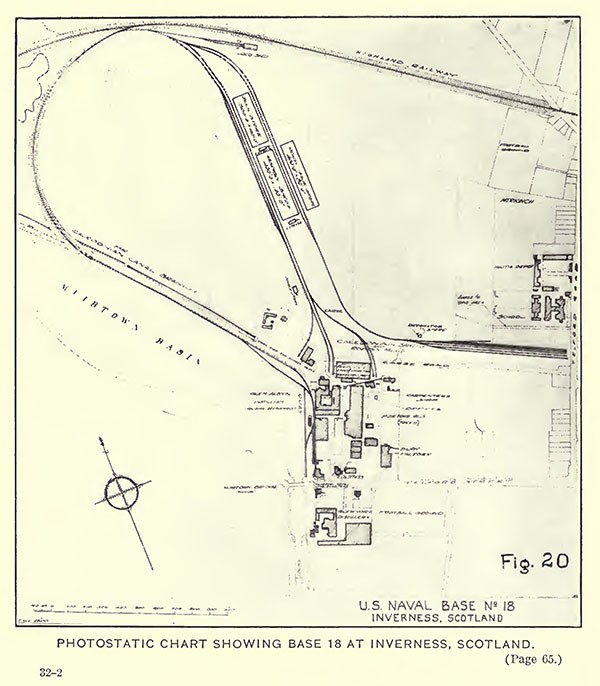

| Photostatic chart showing Base No. 18 at Inverness, Scotland | 32 |

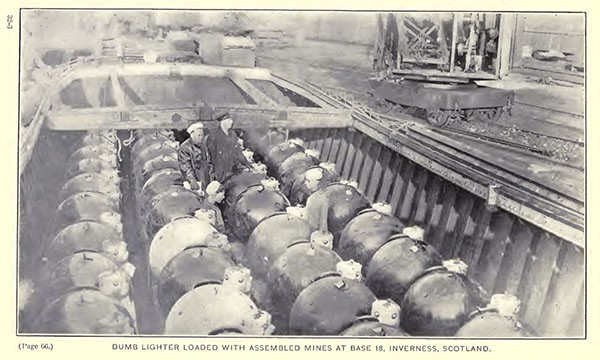

| Dumb lighter loaded with assembled mines at Base 18, Inverness, Scotland | 32 |

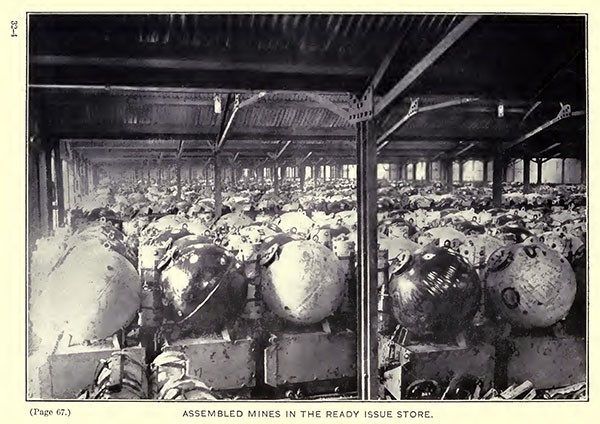

| Assembled mines in the ready issue store | 32 |

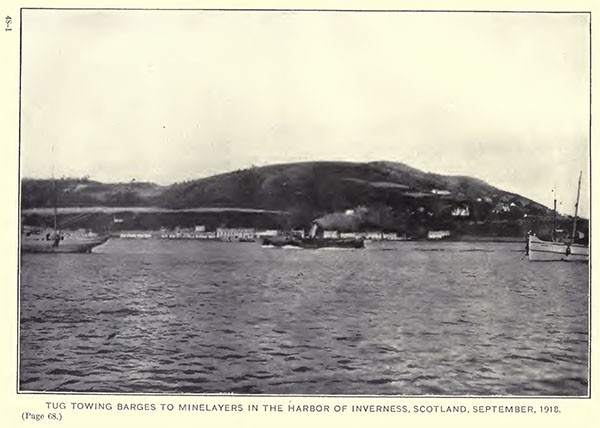

| Tug towing barges to minelayers in the harbor of Inverness, Scotland, September, 1918 | 48 |

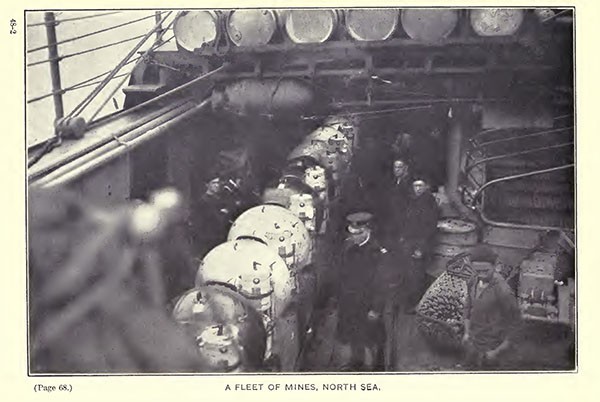

| A fleet of mines, North Sea | 48 |

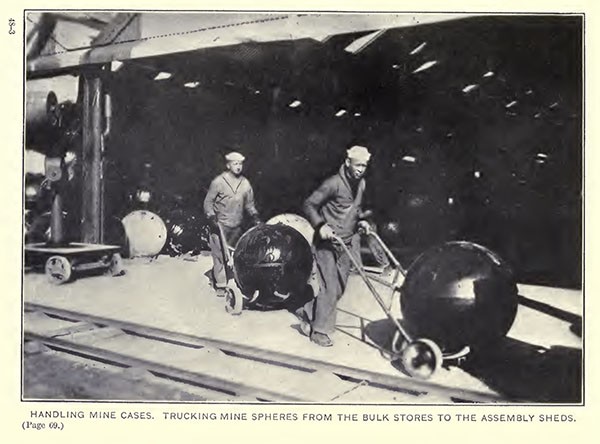

| Handling mine cases. Trucking mine spheres from the bulk stores to the assembly sheds | 48 |

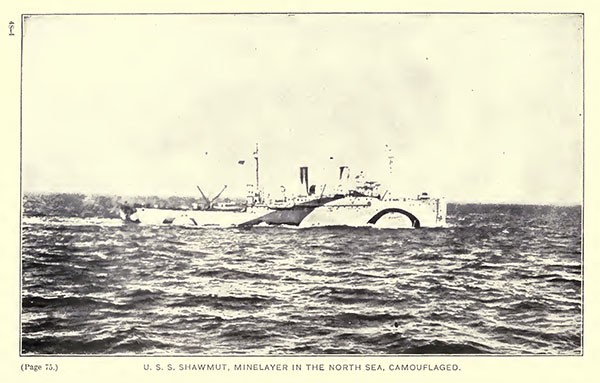

| U. S. S. Shawmut, minelayer in the North Sea, camouflaged | 48 |

| U. S. S. Aroostook, minelayer, camouflaged | 64 |

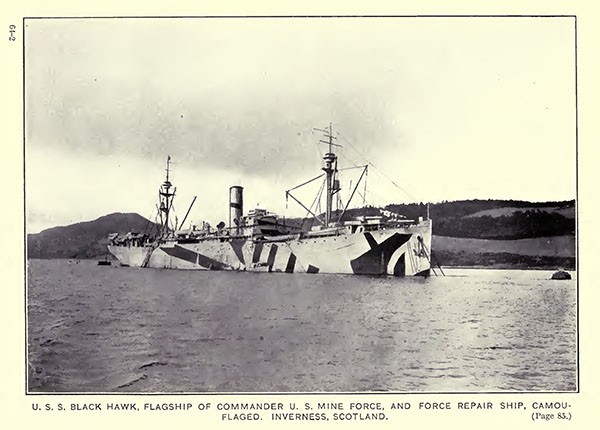

| U. S. S. Black Hawk, flagship of Commander U. S. Mine Force, and force repair ship, camouflaged. Inverness, Scotland | 64 |

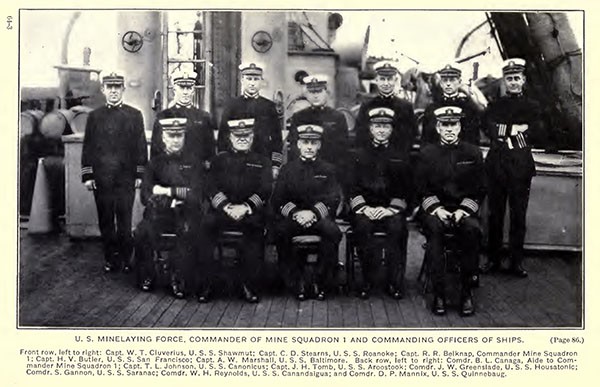

| Commanding officers of U. S. Minelaying Force on board the San Francisco | 64 |

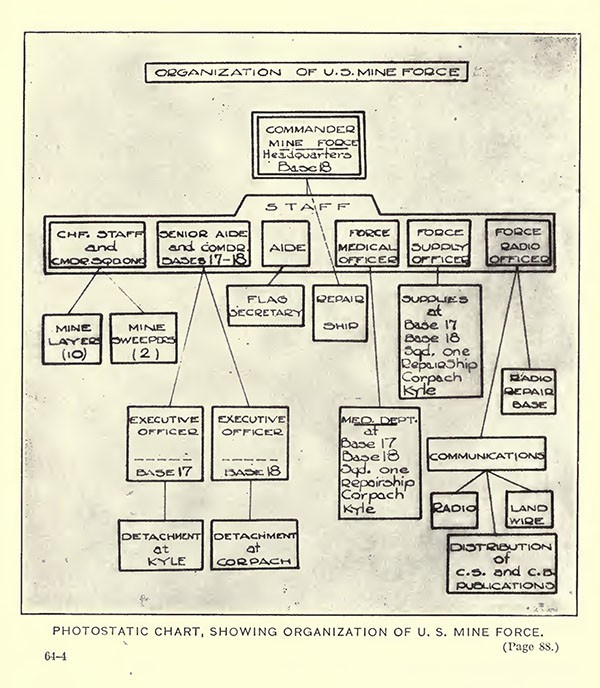

| Photostatic chart, showing organization of U. S. Mine Force | 64 |

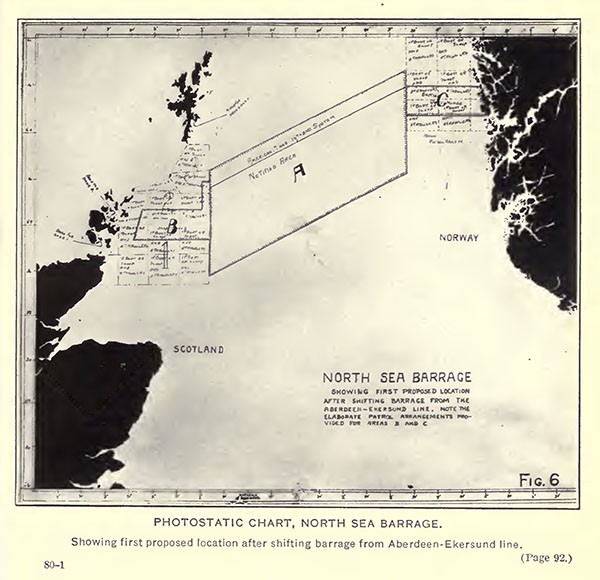

| Photostatic chart, North Sea barrage, showing first proposed location after shifting barrage from Aberdeen-Ekersund line | 80 |

| U. S. S. Baltimore of Mine Squadron 1, North Atlantic Fleet | 80 |

| Bringing mine lighters alongside the U. S. S. San Francisco, of Mine Squadron 1, North Atlantic Fleet, Inverness Firth | 80 |

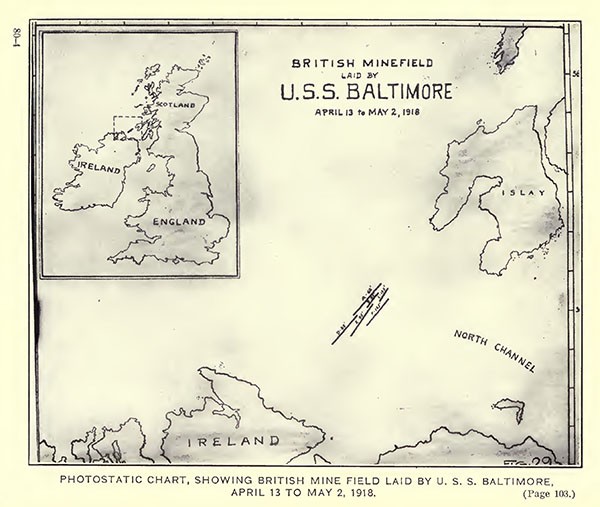

| Photostatic chart, showing British mine field, laid by U. S. S. Baltimore, April 13 to May 2,1918 | 80 |

| U. S. Squadron in planting formation in the North Sea | 96 |

| Minelaying fleet proceeding to sea on a minelaying expedition | 96 |

| Minelaying fleet, North Sea, proceeding to sea | 96 |

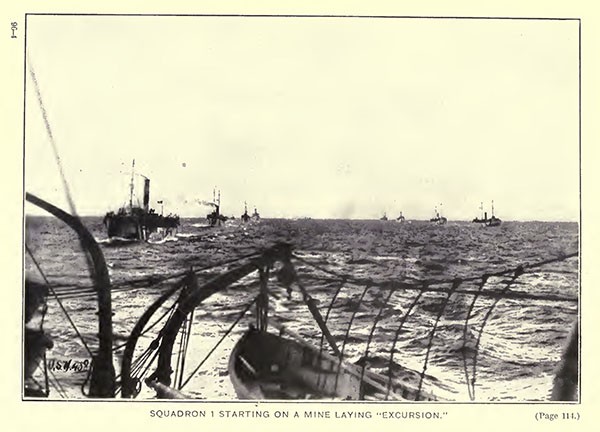

| Squadron 1, starting on a minelaying “excursion” | 96 |

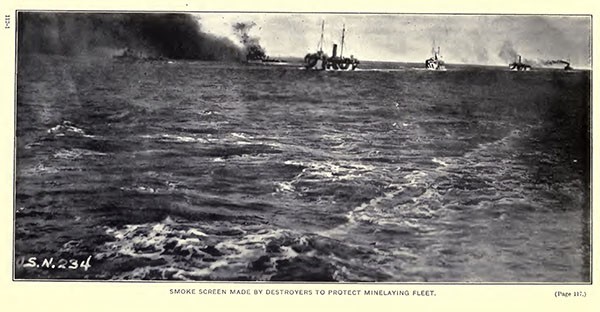

| Smoke screen made by destroyers to protect minelaying fleet | 112 |

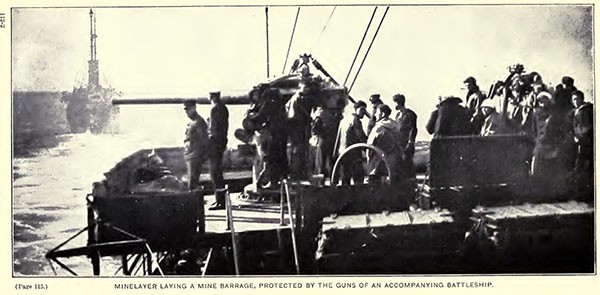

| Minelayer, laying a mine barrage, protected by the guns of an accompanying battleship | 112 |

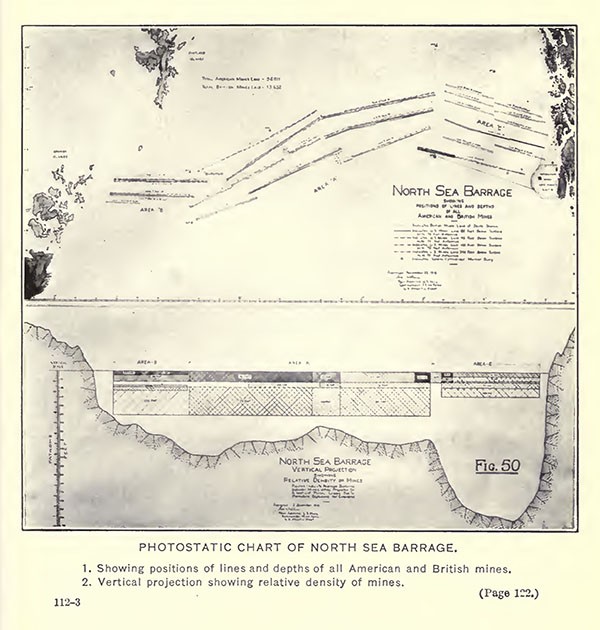

| Photostatic chart of North Sea barrage, showing positions of lines and depths of all American and British mines, and vertical projection showing relative density of mines | 112 |

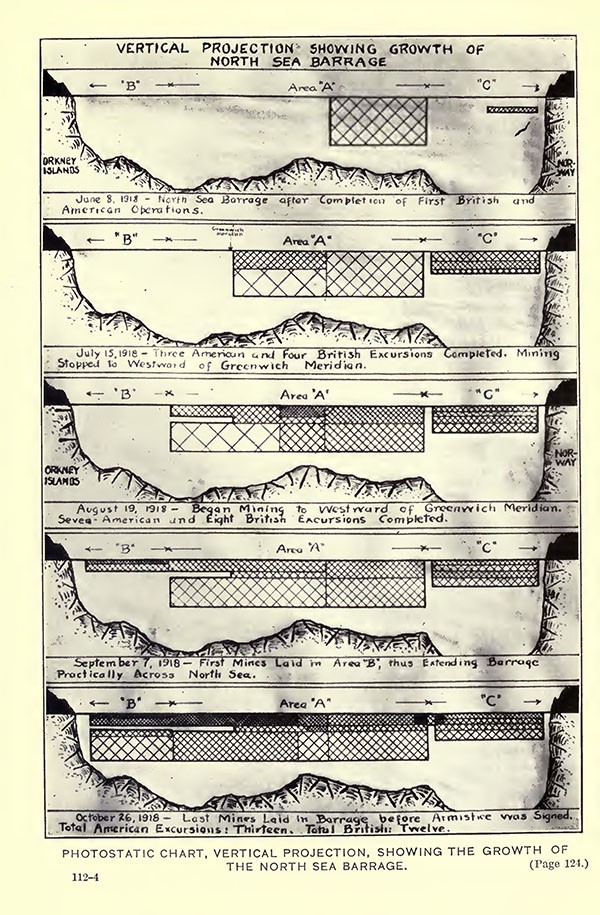

| Photostatic chart, vertical projection, showing the growth of the North Sea barrage | 112 |

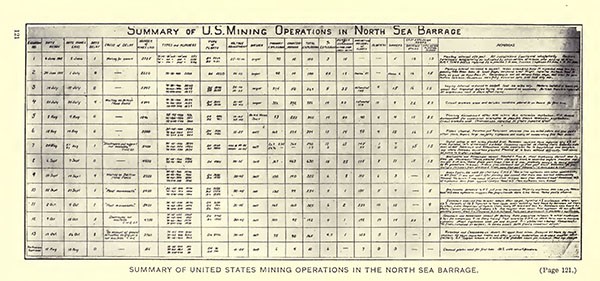

| Summary of U. S. mining operations in the North Sea barrage | 121 |

--5--

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Facing page— | |

| Members of the Allied Conference on minelaying in the Mediterranean, held at Malta, August 6 to 9, 1918 | 128 |

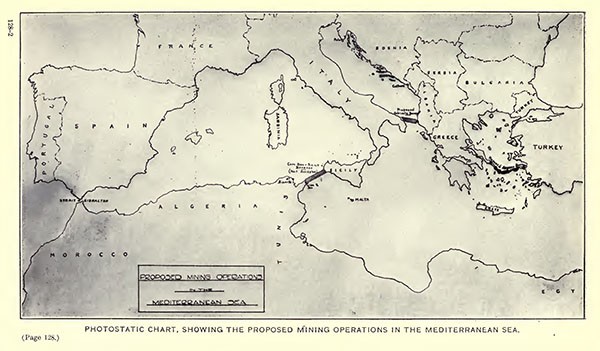

| Photostatic chart, showing the proposed mining operations in the Mediterranean Sea | 128 |

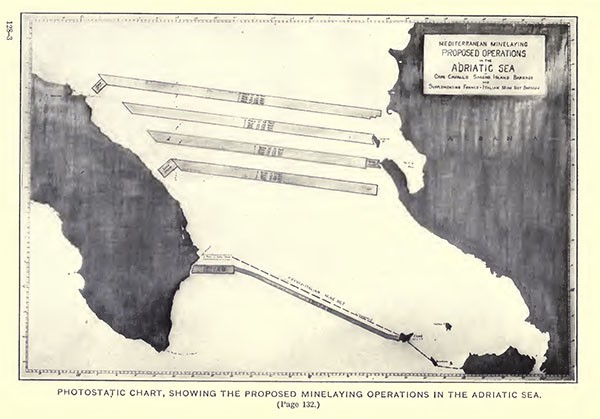

| Photostatic chart, showing the proposed minelaying operations in the Adriatic Sea | 128 |

| Photostatic chart, showing the proposed minelaying in the Aegean Sea | 128 |

--6--

PREFACE.

The mining operations herein described naturally involve two distinct functions:

(a) The design and manufacture of the mines together with all the accompanying materials and their transportation to Scotland.

(b) The most difficult and hazardous sea operation of building the barrage.

The first of these functions was performed by the Bureau of Ordnance of which Rear Admiral Ralph Earle was the chief.

The second of these operations was conducted by Rear Admiral Joseph Strauss.

This report is a compilation from the exhaustive report made by Rear Admiral Strauss, together with that made by Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, the two with other data being combined by Commander Simon T. Fullinwider, and edited in the historical section of the Navy Department.

Referring to the accompanying charts of the mine areas of the world, it is realized that the first impression is that very little of the sea was safe in the European waters and the Mediterranean. While this is more or less true, a careful reading of the meaning of the various forms of shading will give a more correct idea of the actual degree of danger that existed.

C. C. Marsh,

Captain, U. S. N. (Ret.),

Officer in Charge, Historical Section, Navy Department.

December 12, 1919.

--7--

THE NORTHERN BARRAGE.

____________

CONCEPTION AND INCEPTION OF THE NORTHERN BARRAGE1 PROJECT.

_____________

The northern barrage was one of the most important naval projects carried out by the United States during the war. To appreciate the importance of the barrage as a factor in the prosecution and winning of the war, one must consider the general military situation as it existed in April, 1917, when the United States threw her weight into the scales with the Allies. There was every reason at that time for a pessimistic view of the situation. The military situation on the west front was practically a stalemate. The French and British forces appeared to have a slight advantage over the enemy, having made small gains here and there; but they plainly had little or no prospect of obtaining an early military decision. The Italians were holding their own, but with no prospect of decisive victory.

On the east front the Russians were holding for the time being, but there were ominous indications that the newly established revolutionary government would be unable to overcome internal dissensions and that the Russian power might crumble at any time.

In the Balkans the Allies had insufficient force, apparently, to prosecute an offensive campaign; and the growing submarine menace in the Mediterranean seriously threatened the lines of communication by which this force was sustained. In fact, there was grave danger, especially in view of the pro-German attitude of the then Greek Government, that the allied force based on Salonika would have to be withdrawn and the entire Balkan Peninsula given up to the Central Powers. In Asiatic Turkey the British were making slow progress in Mesopotamia; but it was doubtful whether victory there would have any material effect on conditions in Europe.

In short, at the time of the entrance of the United States into the war, there was no prospect of victory over the Central Powers unless and until heavy American forces could be sent to Europe to turn the scale. America was not ready, and could not be expected to create and equip an adequate army within at least one year, or probably two.

___________

1 This barrage was known in the United States as the North Sea barrage; but, since it was termed by the British the northern barrage, and since there were other shorter and minor mine barrages planted in the North Sea by the British, the title northern barrage will be used in this narrative.

--9--

The sending of an American army to France would necessitate the safeguarding of the lines of communication across the Atlantic; in other words, the result of the war was seen to hang upon whether or not the Allies and the United States could obtain and hold the mastery of the sea. As in all wars in which maritime nations have been engaged, sea power was to prove the decisive factor. The British Fleet and the naval forces of the United States and other associate powers were supreme on the surface of the sea, and had it not been for the submarine there would not have been the slightest occasion for doubt of a quick and satisfactory outcome of the war; but the surface fleets were, as a matter of fact, almost impotent in the face of the submarine menace. The German Government concentrated early in the war on the development of the submarine and built these vessels in large numbers, with the purpose, as it turned out, of waging a ruthless war on shipping and thereby bringing Great Britain and her Allies to terms. Generally speaking, the German High Seas Fleet was kept safe at home, while the British Grand Fleet, and other allied heavy naval forces, having no enemy to meet on the high seas, were compelled to wait at their well protected bases until the German Fleet should put to sea. Thus there was little naval activity beyond the submarine warfare waged by the Germans against merchant shipping, and the allied anti-submarine campaign.

The Germans embarked on the policy of sinking merchant ships without warning in December, 1916; and in February, 1917, unrestricted submarine warfare on merchant shipping was formally announced. While the sinking of merchant tonnage had been very considerable up to this time, it rapidly increased until it reached a high point in April, 1917, of 800,000 tons a month. The average for the first six months of that year was 600,000 tons a month, or about 7,000,000 tons a year. It was a plain mathematical deduction that if this condition were permitted to continue, it would assure a victory for the Central Powers within a year, since the diminished merchant fleet of Great Britain and the Allies could not possibly stand this tremendous loss and meet the requirements of transportation necessary to the successful prosecution of the war.

Soon after the United States entered the war it became a settled policy of our Government to send a large force of troops to reinforce the French and British on the west front. The increasing submarine menace gravely complicated the problem of transporting our troops and their supplies, and every known method of hunting out and destroying submarines was given careful consideration by the Navy Department. Aside from the possible heavy loss of life, due to the sinking of American transports by enemy submarines, there was the moral effect of such sinking to be considered; it might react most

--10--

unfavorably on the morale of the entire American Nation and correspondingly cheer the German public.

It became the general policy of the Navy Department to employ every promising means of destroying enemy submarines, and not to be content to rely on any one means to the exclusion of others. The means which proved successful and which were developed, in cooperation with our Allies, to the utmost included the following:

(a) Arming of merchant vessels with guns manned by naval gun crews.

(b) Sending vessels in convoys through the danger zones protected by destroyers and other suitable naval vessels.

(c) "Hunting groups" of vessels of various types equipped with “listening apparatus.”

(d) Aerial patrol by sea planes and "blimps" armed with depth bombs.

(e) Arming of destroyers and other suitable craft with an unlimited supply of depth charges.

(f) Mining of waters habitually traversed by enemy submarines.

The first important anti-submarine plan to give encouraging results was the convoy system, adopted in July, 1917. This plan had the one serious defect of slowing down shipping, since in a convoy of, say 20 or. 30 vessels, the speed of the convoy was reduced to that of the slowest ship; but following the adoption of this plan the average loss fell to about 450,000 tons a month. The losses were principally from slow convoys composed of relatively slow-speed cargo vessels. The losses from fast convoys made up of transports and other craft having a speed of more than 12 knots were comparatively small; and the effectiveness of the system was finally demonstrated by the fact that no troop ships in American convoys were lost during the war. However, the loss of 450,000 tons of shipping a month, or even a much smaller loss, would have proved fatal to the allied cause if permitted to continue; and additional measures were imperatively necessary.

The allied powers were in a very difficult position and were not prepared to quickly put into effect adequate measures against the entirely novel and unexpected form of submarine warfare instituted by the enemy. So far as the United States was concerned, whatever offensive or defensive measures were decided upon, the procurement of the necessary material therefor would take valuable time. In short, the Navy was not prepared for and could not perform its proper functions until after, adequate numbers, or quantities, of destroyers, chasers, guns, mines, depth charges, etc., could be built or manufactured.

Taking the case of mines alone, there were on hand in April, 1917, approximately 5,000 mines of a type which was comparatively

--11--

unsuitable for anti-submarine operations. To show the inadequacy of this supply, it may be stated that the British were using about 7,000 a month and were endeavoring to increase their output to 10,000 a month. Also, the British had found from their own experience that the type of mine possessed by the United States (the Vickers-Elia) was not well suited for the peculiar type of mining in hand and had changed to a new type—a horn mine resembling the German and Russian mines.

Not until after the United States entered the war did the British and other allied Governments furnish us with important military information; but as soon as we were permitted to avail ourselves of their war experience the Bureau of Ordnance decided that it would be desirable to provide at least 100,000 mines and that these must be of a type more suitable for anti-submarine operations than any then in existence. In other words, it devolved upon that bureau to develop a new design of mine and to arrange for its manufacture at the rate of approximately 1,000 a day, or four and two-tenths times the production that Great Britain had succeeded in reaching. The reasoning leading to this decision is given below at some length.

The Bureau of Ordnance, even before the United States entered the war, had made a close study of the general conditions, particularly with reference to possible measures to be taken to counteract the submarine peril. -The mine section of the Bureau of Ordnance, as a result of many conferences on this all important subject with the Chief2 and Assistant Chief of Bureau and also section chiefs, suggested the measures that could be taken by the United States in a memorandum under date of April 15, 1917, a partial copy of which is appended. This memorandum dwelt upon two principal propositions: First, the protection of merchant vessels by means of cellular construction and “blisters”; and second, antisubmarine barrages inclosing the North Sea and the Adriatic. Obviously, it was impossible to consider seriously any proposition to close German harbors as long as the enemy had complete control of his own waters. The next best thing to “closing the holes” was, of course, to close the North Sea by means of a barrage restricting the operations of enemy submarines to the North Sea and preventing their getting into the Atlantic and interfering with the lines of communication between the United States and Great Britain and France. The proponents of this plan freely admitted that such a barrage probably could not be made completely effective, but insisted that even if it were only partially effective it would win the war.

____________

2 At this time, Rear Admiral Ralph Earle, U. S. Navy, was chief of bureau, Capt. T. A. Kearney U. S. Navy, the assistant chief of bureau, and Commander S. P. Fullinwider, U. S. Navy (retired), the chief of the mines and net section, while Lieut. Commander T. S. Wilkinson, jr., U. S. Navy, was chief of the experimental section

--12--

The memorandum was written mainly with a view to crystallizing opinion within the bureau and furnishing a basis for discussion by officers of the bureau with others concerned in the design and procurement of material for increased naval activities.

Within the Bureau of Ordnance practically all officers who would be concerned with such a project quite agreed on the principle that the enemy submarine should be contained by means of such a barrage, though the type of barrage and its location were for a considerable period matters of doubt. The concensus of opinion, however, was that the barrage should extend from the east coast of Scotland to the Norwegian coast. This, together with a short barrage across the Dover Straits, would shut off access to the Atlantic, or at least make the continued operations of enemy submarines exceedingly hazardous and unprofitable.

The proposal to construct a barrage 250 miles long was so novel and unprecedented from every practical viewpoint that it was realized at the time that it would be difficult to obtain a prompt decision without considerable preliminary propaganda within the department. Time was regarded as the supreme factor in the situation, as every day saw the loss of many priceless ships and cargoes.

On April 17 the department cabled to Admiral (then Rear Admiral) W. S. Sims, in command of United States naval forces in European waters, directing him to report on the practicability of blockading the German coast efficiently in order to make the ingress and egress of submarines practically impossible. He, in answer, stated that this, of course, had been the object of repeated attempts by the British navy with all possible means and found unfeasible. Failure to shut in the submarine by a close blockade, using mines, nets, and patrols in the Bight and along the Flanders coast, focussed attention of the department upon plans for the alternative of restricting the enemy to the North Sea by closing to him the exits through the channel and the northern end between Scotland and Norway, as proposed by the Bureau of Ordnance. These are outlined in a memorandum of the Office of Operations dated May 9, 1917, which was to be submitted for the advice and comment of the British Admiralty with its valuable antisubmarine experience. It was noted that, in working up any plan, the whole field of operations was to be considered primarily with a view to attacking the submarine under water as well as on the surface. It was stated that the entrances to the North Sea, while very broad and presenting immense difficulties, came within the bounds of possibility of control. Estimating the cost of gaining this control and confining enemy submarines within the North Sea to be $200,000,000, or perhaps twice that sum, there was no doubt that the United States would devote whatever amount it was worth if the purpose was to be accomplished. This was proposed to be done by establishing a

--13--

barrage of nets, anchored mines, and floating mines, to operate from 35 feet to 200 feet below the surface, which, while safe for surface craft, would bar a submerged submarine, while patrols could deal with those running on the surface.

Commenting on this, the Admiralty, who had apparently considered the United States proposals to particularly advocate the extensive use of nets, replied on May 13:

From all experience Admiralty considers project of attempting to close exit to North Sea * * * by method suggested to be quite unpracticable. Project has previously been considered and abandoned. The difficulty will be appreciated when total distance, depths, material, and patrols required and distance from base of operations are considered.

It was the British experience that nets failed in their purpose on account of the possibility of cutting them; mine nets, when located, were avoided or run over; all were difficult to maintain in place and required too many patrol vessels to watch. Mine barrages were not considered wholly effective unless maintained by patrols at all points. Considering the use of such a barrage from Norway to Scotland, patrols could not be properly protected on such a long line, because the defense would be stretched out in a long and locally weak line, and therefore subject to enemy raids in sufficient force to break through the patrol, cut nets, and sweep mines, and so clear a passage for the submarines. If protected with heavy vessels, these would be exposed to the German policy of attrition with torpedo attack. In short, as concluded by Admiral Sims in his report to the department on May 14, 1917, “Bitter and extensive experience has forced the abandonment of any serious attempt at blockading such passages.”

It is noteworthy that the attitude of the British Admiralty and of Admiral Sims was not favorable to the further consideration of the North Sea barrage project; but, notwithstanding this, the proponents of the project, i. e., the officers of the Navy Bureau of Ordnance, redoubled their efforts to secure its adoption, feeling that the result of the war depended upon it more than upon any other possible measures.

From early in March until the latter part of July, 1917, the mine section of the Bureau of Ordnance made an intensive study of many types of barrage, among them the submarine trap and indicator nets which had been used by the British. Most of the plans considered were devised within the bureau, but in addition a very large number of inventions and suggestions from private sources were studied. Unfortunately, practically all inventions or ideas emanating from nonprofessional sources were based on incomplete knowledge of fundamental conditions and requirements. Their shortcomings may be expressed briefly by saying that they were based on mill-pond conditions, whereas the waters in which such a barrage as that under con-

--14--

sideration had to be planted and maintained were subject not only to very adverse weather conditions, but also to the activities of the enemy naval forces, which, up to this time, had displayed great initiative and resourcefulness.

The types of barrage studied were of three principal classes: First, nets and entanglements; second, nets in combination with mines or bombs; and third, mines alone. The possibility of employing nets or entanglements alone was abandoned early, inasmuch as ’the war experience of the British indicated that it was exceedingly difficult to plant and maintain nets of sufficient weight and strength to be of any material value, and because of the depth of water in which the proposed barrage must be laid was quite prohibitive. The quantity of wire rope required was prohibitive in the time available.

Nets in combination with mines or bombs were open to the same criticism, with the additional point that such material would be very difficult and dangerous to handle and the planting would be too slow.

It was finally decided that mines offered the only practicable solution, and since no mine then in existence, either in America or abroad, was suitable for the project, mainly owing to the excessive number required, it became necessary for the bureau to design a mine especially Adapted to the purpose. A discussion of the evolution of the mine which was finally adopted will follow. It is only necessary to say here that the novel principle of the firing gear of the new mine was discovered in April, 1917, but was not brought -to a state of development warranting its adoption until the latter part of July, 1917.

While from the first the new firing mechanism showed great promise, the officers responsible for its development felt that it would be unwise to place too great reliance on it before it had been thoroughly tested out, and therefore studies of other means of forming a barrage were continued without cessation up to the day that the new mine was adopted. As late as July 15, 1917, a memorandum prepared by the mine ’section was submitted to the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance suggesting mines in combination with nets. The idea was to have a barrage of overlapping light steel wire nets, about 200 feet square, each net carrying two mines, one attached at the top of the net to be a mine with a hydrostatic firing mechanism, and a second, attached to the center of the net, to have a firing mechanism actuated by a propeller in such manner that a submarine carrying away the net would tow the mine and explode it after a short distance. The hydrostatic mine was intended to explode in the event that the sub- -marine submerged it to a certain depth. It is needless to go into details regarding the construction of this net and the designs of the mines, since nothing ever came of it. The plan was submitted to a board, but during the board’s consideration of the project information

--15--

was received of the latest test of the new mine-firing device, which was so favorable that further discussion of the plan before it seemed useless, and the matter was dropped with the understanding that the bureau would concentrate on the development of the new mine, which was thereafter to be known as the Mark VI (up to this time, during its experimental stage, it had been known as the type “X” mine).

In the early days of the mine barrage project, very little official correspondence took place in the matter, principally for the reason that it was desired to keep the matter a profound secret, since it was probable that any type of mine produced would sooner or later bring about methods of counteracting it. It was felt that if information concerning it could be kept until the material had been produced and placed in use, the enemy would not have time to devise protective methods against it.

A decision in the premises favorable to the mine barrage project was daily becoming more imperative in order to accomplish the laying of the barrage during the best weather of 1918; and, therefore, the bureau had prepared by Commander S. P. Fullinwider, U. S. Navy, chief of the mines and net section, a second memorandum, dated June 1, 1917, which bearing a strong favorable indorsement by the Chief of the Naval Bureau of Ordnance, was submitted to the Chief of Naval Operations, this memorandum recommending certain projects for the future conduct of the war and laying particular stress upon the necessity of the northern barrage as being a most promising offensive operation. In fact, the President had addressed the officers of the battle fleet and stated that, as it was nigh impossible to destroy hornets (i. e., German submarines) after they had escaped from their nests, these hornets must be confined to their nests, or destroyed before reaching the vast wastes of the ocean.

Realizing that it is difficult to obtain quick action on a novel scheme of such magnitude as the one under discussion, and especially in view of the unfavorable attitude shown by the British, the chief of the mine section, as a representative of the bureau, departed from the policy of secrecy to the extent of discussing the as yet indefinite plan with several officers who were in a position to further the scheme, notably with a member of the general board, with an officer close to the President, and with representatives of the Office of Naval Operations. He also discussed the matter with Commander C. D. C. Bridge, a British officer then officially visiting this country, who was shortly to return to London. While the type of mine to be used had not yet been developed, it was important to see to it that the idea of a northern barrage should be accepted as a sound and indispensable measure to defeat the enemy submarine. The Bureau of Ordnance, from the first, took the attitude that if the idea of such a

--16--

barrage were only adopted, the project would be carried through in some way or other, as the only question then would be merely a choice of methods and material; and the bureau had no doubt that the material question could be solved in a satisfactory manner. It may be added that the measures above referred to bore fruit, since the project was adopted by the Navy Department without much loss of time after the Bureau of Ordnance reported that a suitable mine had been developed. Furthermore, the President's attitude was known in advance to be favorable; and the project, when adopted by the department, was promptly approved by him.

One of the earliest and most enthusiastic proponents of the northern barrage project was Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, to whom was given a copy of the memorandum of April 15, 1917, and with whom the matter was discussed in a general way. The Assistant Secretary's keen interest in the matter was very apparent throughout the early phases of the project; and it is understood that he took up with the Bureau of Yards and Docks the problem of a net barrage across the North Sea. While the details of this study are not known, it is assumed that effort along that line was stopped when it became known that the Bureau of Ordnance had a suitable type of mine, which, of course, was readily accepted as far preferable to any net plan.

In the month of May, 1917, the Department of Commerce became interested in a barrage proposed by certain officers of the Coast and . Geodetic Survey; and the Secretary of Commerce took up the matter with the Navy Department and strongly urged that the two departments collaborate in designing and putting down such a barrage. It is needless to go into details regarding its design, and the mere statement will suffice that it was to be composed of nets in combination with mines, and that the net was composed in part of insulated wire, the breaking of which wire by a submarine would fire a mine. There were several conferences, one of them presided over by the Secretary of Commerce and attended by Assistant Secretary Roosevelt, Commander Fullinwider, and Lieut. Commander Castle. The Bureau of Ordnance was not favorably disposed toward this plan, because it felt that, even if the necessary quantity of material could be obtained, which was doubtful, it would be a very difficult project to carry into execution, and furthermore, that it would be quite impossible to maintain it in waters such as the North Sea. Plans were adopted to carry out tests in deep water, but interest in this plan ceased when Mr. Roosevelt became convinced that the Bureau of Ordnance had developed a satisfactory mine for a barrage.

The foregoing is mentioned only to show the active and growing interest at that time in the idea of a barrage. It also became a favorite problem with inventors. In short, by the time the bureau

--17--

had demonstrated to its satisfaction that the new mine would be effective, the closing of the North Sea was quite recognized in America as the best possible solution of the anti-submarine problem. It remained to convert the British naval authorities to this view.

The adoption of any plan for a barrage to close the North Sea was, of course, dependent upon the suitability and availability of the material, and so the development of the project was largely the development of the Mark VI mine. It should be stated in this connection, however, that the northern barrage would undoubtedly have been realized whether or not the Mark VI mine had been adopted for the purpose. There were other designs of mine available but the Mark VI was deemed the most promising in sight at that time.

In April, 1917, Mr. Ralph C. Browne, a citizen of Salem, Mass., an inventor associated with the L. E. Knott Apparatus Co., Cambridge, Mass., brought, to the department a description of an invention which he called the “Browne submerged gun.” Assistant Secretary Roosevelt referred him to the Bureau of Ordnance, and the invention was duly considered by the Chief of Bureau and Commander Fullinwider and Lieut. Commander T. S. Wilkinson. The invention in the form offered may be briefly described as follows: A buoy or float carried as an integral part, a so-called gun or short tube extending vertically downward. The buoy carried also a copper wire hanging vertically. A high-explosive shell was carried in the tube or gun. This shell contained in its base a propelling charge of slow-burning powder intended to give the projectile a velocity of about 50 feet per second through the water. The shell was provided with guides to restrict it to travel along the wire. The float carried also an electrical relay mechanism, all parts so related that the contact of a submarine or any steel vessel with the pendent wire would produce a sea-battery current of sufficient energy to actuate the electric relay, which in turn would ignite the propulsive charge in the base of the shell and send the shell along the wire into contact, with the submarine, where the shell was expected to burst and rupture the hull. The design was very ingenious and novel as a whole; but in its then proposed form it was deemed by the Bureau to be wholly impracticable for naval use. Commander Fullinwider saw, however, that the electric principle involved might be applied to a mine firing device; and, after making a study of the matter with Capt. S. J. Brown (Math.), United States Navy, and Lieut. Commander Wilkinson, and after reference of such study to the Chief of Bureau, he suggested to Mr. Browne that he collaborate with the Bureau in applying the new principle to an antenna mine. This Mr. Browne was loath to do as he felt that his invention would be more effective than would a mine. After about two weeks’ investigation, including considerable pressure by the Chief of Bureau himself, how-

--18--

ever, Mr. Browne agreed that he would defer to the bureau’s judgment in the matter and consented to collaborate with the Bureau in the development of a mine-firing device based on the use of a sea battery.

Mr. Browne immediately took up the work, and on June 18, 1917, a crude model of a mine-firing device was tested with promising results at the submarine base, New London, Conn. Further tests were held on July 10; these tests were conducted by the experimental officer of the Bureau. It was immediately subsequent to these tests that it was finally decided to adopt the new firing device, and the Bureau proceeded to design and develop a mine in which this device could be used.

The Bureau was convinced by the tests that the device, which was thereafter to be called the K-1 device, was correct in principle, but realized that in the short time available for development and experimentation it could hardly be hoped to obtain reliability in the mechanical features of the design. However, since it was essential that mines for the barrage should be ready in large quantities by the following spring, it was decided to proceed with the manufacture of the devices and trust to making any necessary modifications after getting into production, and in the meantime to proceed with tests, so far as tests could be conducted without complete mines.

It may be stated here that, although the design of the complete mine had not yet been decided upon, and could not be completed for several months, the mine section of the Bureau of Ordnance was sufficiently assured of the successful development of the mine to submit tentative plans to the Chief of Bureau; and he took the responsibility of formally committing the bureau to this method of closing the North Sea.

On July 18, 1917, the bureau addressed the following letter to the Chief of Naval Operations announcing the development of a new type of mine firing gear which would be suitable for mines for a northern barrage:

Confidential.

July 18, 1917.

To: Chief of Naval Operations.

Subject: Submarine mine barriers, material for.

1. The Bureau has developed a new type of mine, at present referred to as Mark VI (Type X) which it is confidently believed will facilitate the establishment, of submarine barriers. The mine is radically different from other mines in its firing gear, which has been tested out with excellent results and the bureau is now proceeding with the design of the mine as a whole and expects to complete it within two weeks.

2. The new mine will be as easily planted as the ordinary types of naval defense mines and therefore the time and the number of vessels required to establish a barrier will be reduced to a minimum. This mine can be rigged so as to be safe as regards surface vessels, but effective against craft operating below the surface.

--19--

3. The mine will be comparatively simple in design and it is believed that it can be manufactured at a minimum rate of 1,000 per day, which means that the number required for about 300 miles of barrier can be produced within about three months from the beginning of deliveries or within four months from the placing of orders.

4. The Bureau requests that a decision be reached at the earliest practicable moment as to the desirability of establishing complete barriers to prevent enemy submarines from gaining access to the Atlantic. The Bureau assumes that such a project is desirable as no other means of stopping the submarine peril appears to be in prospect, and, since it is going to take four months to obtain the necessary material, the Bureau believes that it should be authorized to proceed immediately with arrangements for procuring the material.

5. Theoretically, only 72,000 mines will be required for 300 miles of barrier, but 100,000 should be provided to allow a reasonable excess for replacements, etc. In addition, a number, say 25,000, should be provided for our own coast defenses, it is believed, making a total of 125,000 mines, which, at an estimated cost of $320 each, gives a total cost of $40,000,000. This estimate is designedly liberal.

6. The Bureau is of the opinion that the design, manufacture, and assembly of the new mine should be carried out with the utmost secrecy and is taking the necessary precautions accordingly, since advance information of such a mine would be of the greatest aid to the enemy in devising means to counteract it.

7. The above estimate as to time is based upon our success in securing the necessary quantity of T. N. T. or other high explosive.

8. In considering this project the use of high-speed mine-laying vessels, such as liners and merchantmen, in addition to destroyers and light cruisers, will be required and such vessels must be provided. The mines can be dropped accurately at any speed by time devices. The whole barrier should be laid as one operation and be protected as far as possible. If isolated mines are planted, it is probable that a device to defeat the mine-firing mechanism will be developed by Germany.

Ralph Earle.

While awaiting the Department’s action, the Bureau proceeded with the design of the mine, with a view to being prepared at the earliest possible date to undertake its manufacture.

On July 30, 1917, the Bureau addressed a second communication to the Chief of Naval Operations, submitting more complete information regarding the new mine and proposing an American-British joint offensive operation in the form of a northern barrage. A copy of this letter follows:

(N3) MC.

July 30, 1917.

To: Chief of Naval Operations.

Subject: Proposed British-American joint offensive operations; submarine barriers;

Mark VI mines.

1. In its letter No. 32957 of July 18, 1917, the bureau announced the development of a new type of mine that is peculiarly adaptable for use against submarines.

2. The firing mechanism of this mine is based on a very recent discovery in the electrical field, and although there has been little time for development the tests which have been carried out with an experimental mine by a submarine leaves no doubt in the bureau’s opinion of the success of this invention.

3. The mine will have the following characteristics:

(a) A spherical mine case carrying a charge of 300 pounds of T. N. T. having a destructive radius of about 100 feet against a submarine.

--20--

(b) The anchor may be either the automatic type, such as that now in use or a simple mushroom type, depending upon the conditions under which mining operations shall be carried out.

(c) The firing mechanism comprises an electrical device carried within .the mine case and an antenna of any desired length, the end of which will be supported by a small buoy as near the surface of the water as may be desired. A second antenna may be suspended from the mine where the depth of water renders this necessary.

(d) A steel vessel coming in contact with the antenna will fire the mine.

4. The mine has the following advantages over other types:

(а) In depths of less than 100 feet it may be planted on the bottom, where it is least affected by wave action and current. In this case a buoyant mine is not necessary or desirable, and it can be made smaller and cheaper than a buoyant mine. In such circumstances there is no possibility of its getting adrift, and it can not be swept up in the usual way. It can, however, be fired by a mine sweep.

(b) In depths greater than 100 feet it is proposed to submerge the mine to a depth of 100 feet, since 100 feet is about its destructive range against submarines. At this depth the mine itself is entirely protected from wave action and only the light float or buoy is exposed to such action.

(c) Where conditions permit the antenna may take the form of a net, or the antennae of adjacent mines may be connected by horizontal wires forming an impassible barrier.

(d) If a floating mine be desired, this mine may be suspended from a buoy in such manner as to be harmless to surface craft but deadly to submarines submerged.

(e) It may be used as a towing mine with antennae to give it a very large danger space.

(f) It can almost entirely replace submarine nets of present types.

(g) It can be used for mining very deep water more easily than can other types.

5. The mine, with its anchor, antenna, and buoy, will be assembled and launched as a unit, so that it can be launched at high speed from destroyers if desired.

6. The bureau believes that with this mine it becomes practicable to close the North Sea, Adriatic, and other exits of enemy submarines, and that it gives us our opportunity to cooperate in carrying into execution a major offensive operation of a decisive character. Even if the proposed barriers should prove to be only 50 per cent effective, the enemy’s submarine campaign would surely fail.

7. It is suggested that the North Sea barriers must extend from the coast of Scotland to Norway and across the English Channel. The proposed line from Scotland to Norway must, to be at all effective, extend into the territorial waters of Norway, thereby involving the question of Norway’s neutrality. It would seem that if the German submarine is permitted by Norway to use her territorial waters, it becomes incumbent upon the Allies to take measures to prevent such use.

8. The proposed mine barrier scheme does not infringe upon the neutrality of Holland, Denmark, and Sweden, except in the restricted sense that the vessels of those powers, as well as of Norway, would be required to pass through a gate in the barriers under the control of the allied forces. In effect, this would amount to the establishment of additional danger zones to be avoided by neutrals.

9. The bureau understands that the British Admiralty has objected to any barrier in the North Sea that would interfere with the freedom of the British fleet. It is suggested that a gate should be left in the barrier at an appropriate place near the Scotch coast, not only for British naval vessels, but also for neutral merchant vessels. This gate would be, say, 8 miles long, with mines so planted that their antennae would not come within 40 feet of the surface at low water. In other words, the subsurface would be mined against submarines and the surface left open. This gate could be effectively patrolled with a very few vessels and submarines attempting to pass on the surface could be destroyed.

--21--

10. If a decision should be reached immediately to proceed with the assembling of the material for these barriers, it would require approximately six weeks to complete the designs, place the orders and start production on a large scale. Alter starting production mines could be obtained at a minimum rate of 5,000 a week, and if the project were given the importance due it there is no doubt that the manufacturers could be depended upon to increase this figure. In this connection it is assumed that the British Admiralty would be willing to cooperate to the extent of furnishing a portion, at least, of the mine anchors, but it is believed that we should supply all of the mines with the exception of the anchors.

11. It would require approximately 72,000 mines to establish barriers around the North Sea, assuming that the barriers will be composed of four lines of mines, placed 100 feet apart in each line, in other words, a barrier would require a mine for every 25 feet. To this 72,000 should be added at least 28,000 for renewals and as a reserve. If it should be decided to place the barrier across the Adriatic and to close the Dardanelles about 50 miles of barrier, or about 15,000 additional mines would be required.

12. It is estimated that 125,000 mines can be manufactured at a cost of $40,000,000.

13. The bureau has made every effort to keep the discovery and development of this mine a military secret, and it is believed that this secrecy can be maintained by proper organization and administration until such time as it becomes necessary to assemble the completed mines to ship them to Europe. To this end, the various parts of the mine will be manufactured by different companies and no manufacturer need be informed as to the characteristics of the mine as a whole. The company which will manufacture the firing gear has taken such precautions that only three members of the company will know that the electrical apparatus used in the mine is intended for a mine.

14.. In view of the importance of keeping this matter a military secret, it is considered desirable that the British Admiralty should not be informed as to the features of the mine until the mines shall have been manufactured and shipped. This view is taken because it is inevitable that information will leak out regarding the design, if any considerable number of persons should become informed of it, and since it is proposed to manufacture the mines complete in this country, it would seem unnecessary to send any information regarding it abroad and would only invite the possibility of such a leak.

15. If the enemy should learn of this invention it would be easy for him to evolve a similar mine which he could use to blockade the British ports. The principle of the firing mechanism is so simple that only the slightest clue would enable the enemy to duplicate it.

16. If this project should be carried out, the bureau is of the opinion that its execution will bring about a general engagement with the German Fleet, which it is supposed is desirable.

17. The following is a summary of the cooperation deemed necessary to carry out this plan:

United States:

(а) Provide mines, except anchors.

(b) Send mines to England.

(c) Assist in assembling mines in England.

(d) Provide a number of minelayers.

(e) Assist in laying.

Great Britain:

(а) Provide anchors.

(b) Assemble mines on anchors.

(c) Organize and equip minelaying force.

(d) Lay all mines with United States assistance.

--22--

18. In the above it is suggested that Great Britain provide the anchors, for the reason that about 30,000 tons would be required and that the transportation of this tonnage should be avoided if possible.

19. Regarding the minelaying part of this project, it is understood that Great Britain has about 18 regular mine layers and that the United States could probably furnish 4, giving a total of 22, not including destroyers. A number of British destroyers are fitted to carry 80 mines, and probably some of ours could readily be fitted to carry 40 to 80 each, so it is assumed that 40 destroyers may be available. The minelaying program may then be assumed to be approximately as follows:

(a) Twenty-two minelayers could lay 200 mines per day each. If they take one day to reload, they would lay an average of 100 per day each. .

(b) Forty destroyers could average 50 per day each.

(c) All combined could lay 4,200 per day.

(d) For the Northern barrier about 60,000 mines are required. These, at the rate of 4,200 per day, could be laid in about 15 days.

(e) For the English Channel barriers, assumed lengths 50 miles, 12,000 mines would be required. At the rate of 4,200 per day these could be laid in three days. It is assumed that two barriers each 25 miles long would be required in the channel to fully protect the Channel crossing.

20. Lacking definite information as to the minelaying facilities in the Mediterranean, but, assuming that 10 vessels could be made available, the Adriatic barrier, 40 miles, could be laid in about one week and the Dardanelles barrier in a shorter time.

21. As the manufacture and assembling of the material will be an immense undertaking, and as time is precious at this juncture in the war, a decision should be reached at the earliest moment practicable.

22. If this plan be adopted, it will be necessary to expedite manufacture by giving this work priority over certain other Government work, particularly in the matter of obtaining a sufficient supply of T. N. T. This will be made the subject of special report if the general plan be adopted.

Kearney, Acting.

On August 15, 1917, Admiral Mayo, Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet, who was about to proceed to England accompanied by certain members of his staff, conferred with the Chief of Bureau and officers of the mine section regarding the new mine and its value for the proposed Northern Barrage. This discussion covered not only the material questions but also matters of strategy and tactics involved in such an undertaking. The Bureau furnished Admiral Mayo for his information and for use in discussing the matter with the British naval authorities a memorandum embodying the ideas of the Bureau of Ordnance concerning the adaptability of the Mark VI mine for a barrage. This memorandum is quoted below for the reason that it set forth with fair accuracy the possibilities and limitations involved in the use of the new mine and, in connection with the above-quoted letters to the Chief of Naval Operations, supplied the information necessary for an intelligent consideration of the Northern Barrage project.

--23--

(D3)MC Confidential.

August 15,1917.

MEMORANDUM FOR COMMANDER IN CHIEF, ATLANTIC FLEET.

Subject: Mark VI mine.

Inclosure: (A) Copy of Bu. Ord. letter to Chief of Naval Operations, dated July 30, 1917.

1. The following notes are intended to amplify and supplement the information contained in the inclosed letter:

2. From the early stages of submarine warfare trap nets have been used to a considerable extent, but it has been found to be extremely difficult to maintain nets of sufficient weight and strength to stop submarines, and it has lately become known that submarines are equipped with cutters which enable them to cut their way through. Inasmuch as the submarine is free to go to a depth of 200 feet, a heavy trap net in deep water necessarily becomes a serious problem, not only to manufacture and plant but also to maintain against the wear and tear due to storms and currents, etc. The Bureau early became convinced that a trap net designed to offer passive resistance to submarines is not a sure solution to the problem.

3. Indicator nets of various designs have been studied and much information regarding foreign types of such nets have been fully considered with the conclusion that this type of net also is not a satisfactory anti-submarine device. Such nets must be suspended from surface floats and cables are subjected to extreme conditions of wear and have a short life. But the principal objection to such a net, when it is not combined with bombs or mines, is that it merely indicates the presence of a submarine and that it requires a very large number of patrol vessels to keep a close watch on the net in order that a vessel may be near at hand to destroy a submarine whose presence is indicated. With a view to reducing the number of attendant vessels, a radio buoy has been developed to send out a call automatically in the event of a submarine fouling an indicator net, but the defect of this scheme is principally that a submarine has an excellent chance to get clear of such a net by the time a patrol vessel could arrive on the scene.

4. Nets in combination with mines or bombs are better, on paper at least, than either the trap nets or the indicator nets; but here again the difficulty of planting and maintaining such nets on a large scale, for example, the proposed North Sea barrier, would be prohibitive. The Bureau has examined and carefully considered hundreds of inventions and suggestions relative to nets of all descriptions, and has come to the conclusion that the only effective barrier that could be manufactured, planted, and maintained effectively is one of mines.

5. The German, British and all other types of mines known to this bureau are unsuitable for the formation of barriers in deep water, mainly because of the great number of mines that would be required for any major operation, such as the North Sea barrier. Since submarines can go with safety to a depth of 200 feet and since the ordinary mine must be actually struck to be effective, one of the first ideas that occurred to the bureau was that pendant mines might be used; that is to say, a number of small mines at intervals of, say, 25 feet, on a vertical pendant 200 feet long, but this was not seriously entertained because it is obviously clumsy and such mines would necessarily have to be supported from the surface by an elaborate system of buoys, cables, and moorings, and such a system would be difficult to fabricate, plant, and maintain.

6. It early became evident that what was needed was a mine that would give a very much larger danger area than any mine in existence, and fortunately the new firing principle embodied in the Mark VI mine was hit upon and proved on test to be entirely practicable.

--24--

7. By giving the mine a sufficiently heavy charge of high explosive, to disable a submarine at a distance of 100 feet, and by making the mine effective by mere contact of a submarine with its antenna 100 feet above and below it, it is apparent that a great advance has been made possible in antisubmarine mining operations.

8. The mine will be charged with 300 pounds of high explosive, probably T. N. T. or a combination thereof with some other substance. The British publications on the subject of depth charges allot a danger radius of 70 feet to a charge of 300 pounds of amatol (60 per cent T. N. A. and 40 per cent ammonium nitrate). From French information and from experimental data in possession of the bureau, it is concluded that the positive destruction area of such a charge is within a radius of 70 feet, but that within a greater area of a 100-foot radius sufficient damage may be expected to force the submarine to come to the surface. Accordingly it is considered that the use of these mines with an antenna 100 feet above the mine and another 100 feet below the mine will permit the explosion of the mine upon the passage across its vertical plane in contact with the wires of any submarine within 100 feet above or below the mine. It will readily be seen that this increases the effective “contact area” in the ratio of the 200 feet length of the antenna to the 3 feet diameter of the present contact mine in use by the Allies. In other words, one mine will cover all practicable depths for a submarine, as it is not probable that submarines will cruise below 200 feet depth. The “contact area” of the mine may be still further enlarged by transverse antennae connected to adjacent mines forming a network, but owing to the difficulties of laying such a barrier in the open sea, it is considered preferable to lay several parallel rows of unconnected mines.

9. Anchors will be of three different types, viz:

(а) Automatic anchor, similar to present British type, for use where automatic depth regulation is desired.

(b) Nonautomatic anchor for use in depth of less than 100 feet; fixed length of anchor cable to hold mine close to bottom where effects of wave action and current will be minimized.

(c) Modification of (b) nonautomatic anchor for depths exceeding 100 feet, but where depths are fairly uniform. Length of anchor cable to be set for predetermined depth to give mine submergence of 100 feet.

10. The third type of anchor (c) is desirable only to save time of manufacture, it being simpler than an automatic mine, but it would require more time and care to plant owing to the necessity of knowing the depth fairly accurately. Its principal use would be in home or controlled waters.

11. In view of the fact that the mine will be at a depth of 100 feet or on the bottom (in depths less than 100 feet) it will be affected by wave action and the effect of current will be less than with the usual type of mine, therefore the mine anchor can be lighter than that of other mines. It is proposed, however, to back the anchor with a small light anchor (in combination with the plummet or otherwise) to insure holding.

12. All anchors of whatever type will, of course, fit the standard mine track, and all mines, regardless of type of anchor, will be launched in the same manner.

13. The scheme of mine laying contemplates separating the mines in each line by a distance of 100 feet, and laying four separate lines, mutually distant 500 yards and whatever distance is found necessary for safety and convenience in laying. In this manner a barrier of practically one mine per 25 feet (since in all probability the several lines will be staggered with respect to each other) will be created. It is estimated that it would be well-nigh impossible for a submarine to pass through the four lines without striking a mine in some one of the lines. This distance apart of 100 feet insures freedom of the mines from countermining each other.

14. If the upper antenna is made of such length that it reaches the surface, the passage of surface craft coming in contact with the antenna will fire the mine. This

--25--

may be prevented in cases where it is desired to leave “gates” open for the passage of the fleet by submerging an antenna to a depth of 50 feet. This will probably suffice to strike all submarines operating entirely submerged, because it is understood that they cruise usually at a depth of 60 feet in order to avoid fouling the bottom of surface craft which they can not see. The surface of these gates must, of course, be thoroughly patrolled in order to prevent the passage of submarines on the surface, or submerged but with periscope showing. In case, however, of explosion of one of the mines by a surface vessel, serious damage would unquestionably result to a merchant vessel. War vessels, however, by reason of their superior strength and interior subdivision, would be able to stand with comparatively little damage, the explosion of the mine at a distance.

15. For a barrier to be completely effective against submarines, the entire depth of water from the surface to 200 feet should be mined; in other words, the buoy of this mine should reach almost to the surface in order that a submarine on the surface might be destroyed or seriously damaged. With a barrier of this kind, great care would be necessary to keep friendly vessels away from the danger zone, and to this end it would be necessary to put down navigational marks, either vessels or buoys, to mark the danger zone and to facilitate the work of additional mine planting when such becomes necessary.

16. The use of a steel sweep metallically connected to the sweeping vessel with a steel underbody would explode the mines. This presents two advantages:

(a) In case of sweeping by the enemy no mine can be picked up and the construction thereof examined.

(b) After the war the mines may be readily removed by exploding them. If the recovery of the mines for stowage and use is desired, however, this can readily be done by using a parcelled sweep and insuring that the sweep is connected to the sweeping vessel by means of some nonmetallic joint.

(c) The proposed plan of laying these mines contemplates their use in waters where enemy sweeping operations could not be carried out without driving off the patrol.

17. The mine is protected from premature firing by two breaks in the electric circuit. The first of these is closed by the hydrostatic pressure of the water after the mine is launched. The second is not closed until the contact of the submarine or other steel vessel with the antenna. The second break is further protected by a mechanical lock not liberated until hydrostatic pressure is applied on the mine on submergence, and by an electrical ground which is not connected until the mine is in the water and the buoy and antenna have paid out. The rugged character of this safety device and its efficiency have been amply demonstrated by tests. Still another safety device is an “extender” which forces the primer into firing position relative to the detonator only after submergence of the mine to a predetermined depth.

18. The firing element of the mine is a dry-cell battery completely sealed up. It is estimated that the life of this battery as thus sealed is at least two years, with probably much longer life.

19. There are no insulated electrical parts outside the mine case. All electric circuits within the case are carefully insulated, and in addition they carry such feeble currents that there is no difficulty to be anticipated from short circuits, grounds, or defective insulation. The lower antennae wire must be metallically insulated from contact with the bare metal of the mine case or the mine cable. This can be accomplished by coating the mine with a nonmetallic bitumastic compound and by parcelling the anchor or mooring cable. Electrical insulation is not necessary, simply mechanical insulation to prevent actual contact of the two bare metals.

20. The action of pronounced currents especially where the mine is laid in very deep water, would be to deflect the mine from the vertical and consequently, since

--26--

its mooring rope is of fixed length, to increase the submergence of the mine to some degree. This difficulty may be overcome by floating spare lengths of antennae on the surface, so that when by current action the mine is submerged, the spare length then becomes an additional antenna buoy, now somewhat submerged. The tilting action on the mine will not prevent the operation of its mechanism. In addition, the deep submergence of the mine will remove it to a large extent, from influence by surface currents and wave action, and will subject it only to legitimate deep currents which do not, in the water in which it is proposed to lay these mines, reach any high value.

STRATEGICAL AND TACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS.

21. In order to present a fair chance of success, these mines must not be laid as surprise mines in waters wherein the enemy has control, but must be located at a distance from enemy bases sufficient to insure absolute control of the waters by the allied forces. This would then insure the maintenance of an adequate and continuous patrol and the prevention of sweeping operations.

22. In planning for the material required for the North Sea barrier, the line from Buchan Ness, on the east coast of Scotland, to the coast of Norway was assumed as a possible line. This line is an extreme example of a barrier because of its length and the depth of water traversed, though its currents are favorable.

23. It is evident that such a barrier would restrict freedom of action of the British fleet based on the coast of Scotland, inasmuch as it would not be free to cross the barrier line at any point except where a “gate” had been established. This gate could be any width desired, say, 15 or 20 miles, and there could be more than one gate.

24. Assuming that the North Sea were inclosed by effective barriers, and assuming that the enemy had 200 submarines in the North Sea and confined thereto, it is to be expected that the enemy would attempt to trap the allied forces. For example, suppose that a gate 20 miles wide were left in the barrier, near the coast of Scotland, and that this was the only means by which the allied fleet could pass in and out of the North Sea. It is to be expected that the enemy might dispose his submarines in appropriate positions in the neighborhood of such gate, that he would then send his main fleet into the North Sea to make a demonstration and try to draw the British and allied forces into an ambush. The important question arises, therefore, as to whether the British and allied fleets could reasonably expect to cope with such a situation. It seems reasonable to expect that by means of patrols and sweepers a large area of sea adjacent to the proposed gate could be kept under control and made fairly safe for the fleet. However, denial to the German submarines of access to the Atlantic would intensify submarine activities in the North Sea. The enemy would also be likely to attempt to raid and sweep or destroy parts of the barrier. This would necessitate constant and vigilant patrol by fast, light cruisers and destroyers, and it is to be expected that this condition would bring on heavy engagements with the enemy if not a main-fleet action.

27. Further tests are about to be made of a number of mines to demonstrate their reliability under varying conditions of service, and their safety in handling, but as the firing gear is the only really novel feature of the mines, and as that has stood every test yet applied to it, there appears to be no possibility of failure.

28. The manufacture of 10,000 mines for our own service has been started. This initial lot of 10,000 will prepare manufacturers concerned for production of larger quantities.

T. A. Kearney, Acting.

--27--

As will be subsequently seen, the tentative design of the mine had to be modified as a result of experiments and more mature study of the project. Notably, the use of a lower antenna was decided to be impracticable or inadvisable; and the spacing of mines had to be increased to 300 feet to reduce the danger of countermining. It was found, too, that the Bureau of Ordnance had been too optimistic in its forecasts relative to early completion of design and early production, due principally to the lack of sufficient experienced personnel in the early stages of the project.

The foregoing carries the history of the northern barrage to the point of its formal submission to the British Admiralty by the Navy Department through Admiral Mayo.

--28--

BRITISH CONSIDERATION OF PROJECT.

____________

A British Admiralty “History of Northern Barrage” states that—

Toward the end of August, 1917, Commander (Acting Capt.) Alan M. Yeats-Brown, D. S. O., R. N., after having made various proposals during the preceding two months with regard to anti-submarine measures, produced a paper entitled “Anti-submarine Mining Proposals.” This paper was referred to the plans division. This division had already been considering these matters for some time, and, after consulting with Capt. Yeats-Brown on several points which he had brought forward, suggested certain modifications to the proposals and wrote an appreciation on Capt. Yeats-Brown’s paper. The conclusions arrived at were brought up for discussion at the next allied naval conference by the First Sea Lord, who, it is believed, had previously discussed the matter with Admiral Mayo, of United States Navy.

The northern barrage project was taken up at an allied naval conference at London, September 4-5, 1917, attended by Admiral H. T. Mayo, United States Navy, where, as reported by him on September 8: “The British Admiralty put forward, as an alternative to a close offensive in German waters, the suggestion that the activity of enemy submarines might be restricted by the laying of an effective minefield or mine-net barrage.” The mine-net barrage was considered impracticable and “as to the proposal to put down a mine barrage in the northern part of the North Sea, while it could be guarded against enemy sweepers, certain difficulties exist such as lack of freedom of movement of the Grand Fleet, so that a very promising degree of success should be indicated before such an undertaking was begun.” Further, “the conference, after discussion, agreed that the distant mine barrage could not very well be undertaken until an adequate supply of mines of satisfactory type was assured.”

The British Admiralty history, in reference to the proceedings at this conference, states:

Admiral Jellicoe put forward the suggestion of laying “an efficient barrage so as to completely shut in the North Sea.”

He computed that 100,000 mines would be required. He remarked (a) “I do not think we get many German submarines by mines”; (6) “It appears that the result of our mine fields (in the Bight) is to force the submarines, or a very large proportion, to go in and out of the German bases through territorial waters or Dutch territorial waters”; (c) “There is the alternative of laying a mine field in the North Sea in a position where the enemy sweepers can not reach without running very considerable risk. In view of our present experience I do not think that would have much more result than our present policy; but if a mine is produced which is more effective against submarines than our own mines the matter perhaps becomes somewhat different. * * * We get our mines slowly. Our problem is then: Is it better to put them down as we get them or is it better to wait until we get a very large number

--29--

and lay a complete barrage across the North Sea? * * * It is obvious a mine field so laid would have to be at some considerable distance from German ports, because it would require to be watched. * * * A great deal depends upon whether the mine is a satisfactory one. If we get a satisfactory mine, it might be worth while laying a barrage when we get a sufficient number.”

Admiral Mayo approved the idea of a mine barrage involving patrol by the allied fleet, provided always that we had. confidence in the efficiency of the mine which would be laid. He thought that this promised really more in the way of results than the proposed operations in regard to the convoy of ships.

Vice Admiral Sims said, “It must be successful completely or it is not successful at all. Either the barrage is successful absolutely or it fails absolutely.”

Sir Eric Geddes said, “I do not understand from the remarks of the First Sea Lord that the barrage should take the place of other offensive measures. It is not considered that the barrage can be sufficiently relied upon to take the place entirely of other measures for hunting and destroying submarines.”

As for Sir Eric Geddes’s statement, he was in exact accord with the American proponents of the project, who, from the first advocated it in addition to other useful antisubmarine measures.

The results of the conference may be summed up as indicating a favorable attitude in principle toward the northern barrage project leavened with doubt of its practicability. The reasons for this doubt are surmised to have been the generally unfortunate experience of the British in the development and use of mines. At the outbreak of war in 1914 the British had practically no mines, and, for want of a better one, adopted the Vickers-Elia type, which soon proved unreliable and ineffective." This was superseded by one of British Admiralty design, essentially similar to the Russian and German horn mines, but with a distinctly British sinker (anchor). This British horn mine, while perhaps an improvement on the Vickers-Elia, was not entirely satisfactory, being comparatively dangerous to handle, too susceptible to countermining, unreliable in automatic depth taking, and not of a type lending itself to rapid and economical manufacture.

For some reason, perhaps their own rather slow and unsatisfactory progress in the development of mines, British officials apparently were skeptical of the ability of the United States to produce quickly a more satisfactory type. This attitude first became apparent to the Bureau of Ordnance on June 2, 1917, when Admiral Sims, in a dispatch to the department, reported: * * * "the British Admiralty have concentrated upon the construction of mines to such extent that they now anticipate that by August the output will reach 10,000 a month. They consider it unwise from their previous experience with mines similar to those which we now have on hand to attempt to utilize our present available supply. They now consider * * * as our output of a different type mine would not be available in sufficient time, that we can more profitably concentrate on other work.”

An immediate result of the conference was the production on September 14, 1917, by the Admiralty plans division of a paper for

--30--

Admiral Mayo entitled “ General Future Policy, Including Future Mining Policy” with an appendix, “Mine Barrage Across the North Sea.” The following extracts from this paper bearing on the barrage project are quoted:

The enemy submarine campaign now dominates and overshadows every other consideration, and any increase in the present rate of sinking might bring about an unsatisfactory peace.

* * * it therefore appears that our future policy must be directed toward a more concentrated and effective control in the areas between the enemy’s ports and our trade routes.

Some form of barrage corresponding to that which was formerly established by the battle fleet * * * must be reconstituted in such a form that the enemy submarines can not venture into it without considerable risk to themselves.

Broadly speaking, four forms of barrage may be considered—

Firstly. A barrage of mines only * * *.

Secondly. A combination of deep mines with surface and aircraft.

Thirdly. Surface and aircraft patrolling a wide belt.

Fourthly. Sealing the submarine exits * * *.

The fourth form of barrage * * * is the only radical cure * * * but the difficulties * * * are so great that it is not recommended to attempt it.

It is therefore proposed to use a combination of the first three.

* * * The enemy submarine would thus be subject when on the surface to attack of one kind or another from shortly after leaving their bases until they cleared the Orkney-Shetland-Norway line, in addition to passing through a mine barrage * * *.