The Navy Department Library

Chapter 7: Back to the Parallel

History of US Naval Operations: Korea

Part 1. 10 July–11 September: Preparing the Counterstroke

Part 2. 15 August–21 September: North to Inchon

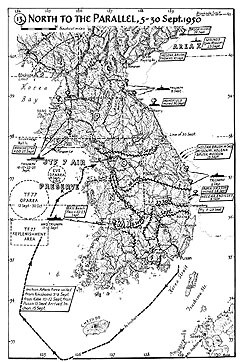

Part 3. 12 September–7 October: The Clearance of South Korea

Part 1. 10 July–11 September: Preparing the Counterstroke

From the first days of war General MacArthur had hoped to deliver a counterstroke directed at the Inchon-Seoul region, the strategic solar plexus of Korea. Early in the fighting he had conceived the idea of landing the 1st Cavalry Division at Inchon, and from 4 to 8 July the staff of Amphibious Group had grappled with this problem. But the rapid advance of the enemy, which forced abandonment of this scheme in favor of the decision to land the cavalrymen at Pohang, made it plain that translation of idea into actuality would involve an assault landing, and posed a requirement for amphibiously trained troops. Not unnaturally, therefore, the 10th of July, the day the Pohang landing was decided upon, was also the day of CincFE’s first request for an entire Marine division.

Twice repeated in the days that followed, this request bore fruit on 20 July, with JCS approval of the movement to Korea of the 1st Marine Division, Major General Oliver P. Smith, USMC, with an arrival scheduled for November or December. But on the next day a most urgent request from CincFE for a reconsideration of this date was accompanied by his statement that its arrival by 10 September was "absolutely vital . . . to accomplish a decisive stroke." And on the 25th General MacArthur was informed that the 1st Marine Division, with attached air but less one RCT, had been ordered to prepare for a departure between 10 and 15 August.

That this commitment was met was in itself an extraordinary administrative accomplishment. Starting with a total Fleet Marine Force strength of 28,000, less than half of which was in FMF Pacific, it took some doing to provide a division of more than 20,000 men, not to mention the 4,000 or so additional personnel of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, without complete disorganization of the Fleet Marine Force Atlantic, and of the supporting establishment. Only the President’s decision of 19 July to call up the Marine Corps Reserve enabled the Joint Chiefs to promise the division; only Marine confidence that an expedited arrival was both desirable and feasible produced the advanced departure date; only the availability of sufficient amphibious lift permitted this confidence. By such interlocking circumstances CincFE was enabled to plan for a mid-September operation, but late July and early August was inevitably a time of controlled frenzy at Camp Pendleton, as security detachments, personnel from FMFLant, and reserves were processed and integrated into the violently expanding force. Difficult enough in itself, this work was further complicated by the need to provide replacements for the brigade in Korea, a requirement which was met beginning in mid-August by a series of troop movements flown west by MATS. Yet despite all obstacles loading of the division was begun on 8 August, two days ahead of schedule.

Up to this time the division promised General MacArthur consisted merely of a second RCT, the 1st Marines, plus supporting and headquarters troops and the balance of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. But on 10 August, as the brigade was attacking through Taedabok Pass and as the second embarkation was beginning at San Diego, the third RCT was provided and a third mobilization begun by orders to activate the 7th Marines.

The arrival of this regiment in the theater of action would constitute a striking demonstration of what can be accomplished by a force with a high degree of readiness when provided with advanced forms of transportation. One-third of the regimental strength was taken from the 2nd Marine Division on the Atlantic Coast, one-third was made up of Marine Corps Reserves summoned to active duty, and the remainder was provided by a battalion of the 6th Marines, then in the Mediterranean, and by personnel from miscellaneous posts throughout the United States. Five weeks and two days after its formal activation on 17 August, this regiment was in contact with the enemy, and the convergence upon Camp Pendleton of personnel from all over the United States had been followed by a convergence through 260 degrees of longitude, westward from the Atlantic coast and eastward from Crete, upon Inchon. The critical days of mid-August which saw the Marine Brigade rushed northward toward the Naktong, the departure from the west coast of the first elements of the division, and the flight westward over the Pacific of the division commander and his staff, saw also the sailing from the Mediterranean of the AKA Bexar and the APA Montague with the 7th Marines’ prospective 3rd Battalion.

By now some intellectual order had been made out of the Korean chaos, at least on the upper levels of command, by the imposition of a three-phase concept upon the operations in the peninsula. The first of these phases involved the halting of the North Korean advance, the second the reinforcement of U.N. forces in the perimeter to permit offensive action, the third the amphibious counterstroke. Yet these phases were not wholly separable; planning for phase three had to begin before the success of phase one was assured; the requirements of the first two phases had serious implications regarding the availability of forces for the Inchon landing.

This had been conceived of as a two-division operation, with the 1st Marine Division leading the assault. The timely presence of this unit in the Far East now seemed certain, but one of its RCTs was fully committed within the perimeter and one would not arrive in time for the initial landings. Given the continued shortage of forces in the theater, certain specific problems required solution before the planning could go forward. The availability of the Marine Brigade had to be assured; another division had to be found to follow the Marines across the beaches; a corps headquarters was needed to supervise the post-assault conduct of the campaign.

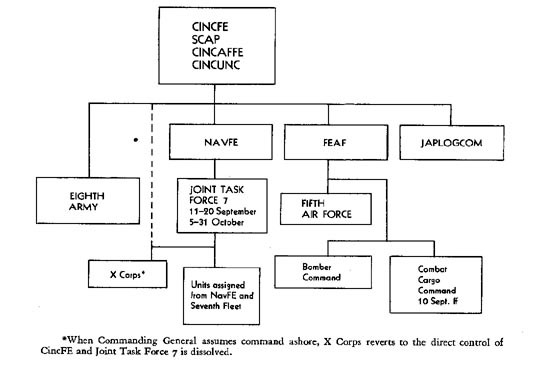

As to the first requirement, release of the brigade was promised by CincFE and the bad news communicated to General Walker. The follow-up assignment was given the 7th Infantry Division, Major General David G. Barr, USA, the last of the pre-war divisional units of the Far East Command, which had been first skeletonized to fill the ranks of units committed to Korea and then strengthened by the integration of some 8,6oo South Korean recruits. To solve the command problem it was proposed either to borrow a ready-made organization from the staff of Fleet Marine Force Pacific, at Pearl Harbor, or to create a provisional corps headquarters from personnel available in Japan. Although the Marines were eager, the decision of CincFE was that the organization of a provisional X Corps Headquarters would be accomplished locally; command of the corps would be entrusted to Major General Edward M. Almond, USA, Chief of Staff of the Far East Command.

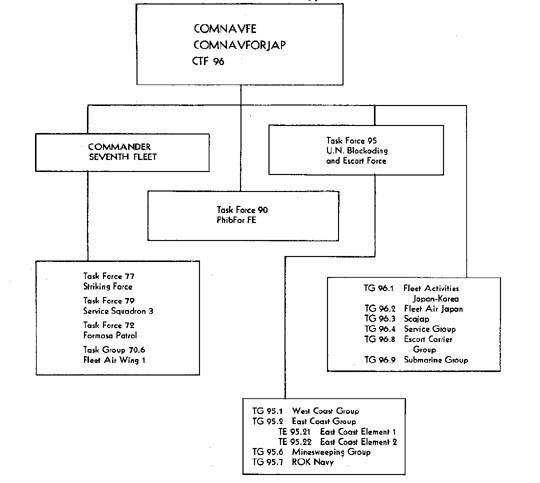

With the landing force provided for, it remained to get it there and put it ashore. This would be the job of the naval components of Joint Task Force 7, the combined force of which X Corps formed a part, command of which was assigned to Admiral Struble. The mission of Commander JTF 7 was to land the X Corps on D-Day at H-Hour on the west coast of Korea in order to seize and secure Inchon, Kimpo airfield, and Seoul, and sever North Korean lines of communication. This accomplished, the harvest would follow as X Corps, in conjunction with a planned offensive by Eighth Army and with the help of theater air and naval forces, would destroy the North Korean Army south of the line Inchon-Seoul-Ulchin.

Much of this preliminary planning was water over the dam by 22 August when the commander of the 1st Marine Division reached Tokyo. CincFE had published his directive for "Chromite" on the 12th, and ComNavFE’s derivative operation plan had been issued on the 20th. General Smith had previously heard only rumors of his task, but now he got the word. Two hours after his arrival, following a hasty fill-in by the Navy planners in Tokyo, the Marine commander had an audience with General MacArthur at which CincFE communicated his vision of the inevitable victory.

There followed two days of conferences of an extraordinary nature. Two members of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Sherman and General Collins, had flown out from Washington; Admiral Radford and General Shepherd had flown in from Pearl; Admiral Joy and Admiral Doyle were there, along with numerous high-ranking officers from CincFE’s headquarters. In these discussions it speedily became clear that in Tokyo the amphibious techniques which Navy and Marines had brought to high perfection, and which dominant Washington opinion considered obsolete, were held in the greatest esteem. The situation, indeed, was almost embarrassing, for without denying the strategic importance of Seoul or the desirability of its capture, naval and Marine planners could not forget the extraordinary tides and currents of the Yellow Sea, the mud banks which restricted and the islands which pockmarked the long approach to Inchon, and the absence of suitable landing beaches at the objective. Not since Admiral Rodgers sent them against the Han River forts had the Navy or Marines undertaken such a maneuver; Rodgers, at least, had not sent his landing force into the heart of a city; the last such effort, the British raid on Dieppe, had not proven an experience of a sort to inspire confidence in this type of assault.

Although the rule book says that what is tactically impossible can never be strategically desirable, the doubts of the experts were of no avail. The Commander in Chief was firm, both as to the amphibious assault and as to the objective, while the headquarters staff, seeing the strategic desirability clear, seemed to feel that tactical obstacles could be solved by the issuance of orders. Naval reservations were brushed aside, and increasingly the conferences took on the air of the attack on stout Horatius, when

. . . those behind cried, "Forward!"

And those before cried, "Back!"

Navy doubts about the proposed operation had developed well before General Smith’s arrival, and had led ComNavFE’s staff to investigate some possible alternatives. In the search for a better objective the fast transport Horace A. Bass had been sent into the Yellow Sea and provided with fighter cover by Badoeng Strait; there between 20 and 25 August, and despite the presence of a full moon, her raider and UDT group had conducted night reconnaissance of possible beaches north and south of Kunsan, and of one in Asan Man, 38 miles below Inchon. But these efforts came to naught. Although preliminary plans had been developed for Kunsan, and although Admiral Sherman and General Collins both favored a landing in this area, the suggestion was ruled out by CincFE. Even General Shepherd, whose early support of Inchon had helped in the materialization of the Marine Division, had by now developed second thoughts, but his plea for the Asan Man alternative suffered the same fate.

Having felt themselves somewhat in the dark, the dignitaries from Washington had come out to see what was going on. Now they knew. At the final conference the best that Admiral Doyle could say about Inchon was that it was "not impossible." There the situation rested. None would gainsay CincFE. And while formal approval of the Joint Chiefs had still to be obtained, Admiral Sherman’s agreement to support the plan and the appointment of Admiral Struble to command the operation had already shifted the emphasis from debate to action.

At Sasebo, having learned of his large impending responsibilities, Struble had been expanding his staff. A squadron commander was lifted from the destroyers, an air planner from Admiral Hoskins’ staff, and on the 25th, leaving his flagship to follow him, Commander Seventh Fleet flew to Tokyo. There, where all principal commanders were now united, there was plenty of work for all. The west coast contingent of the Marine Division was expected to reach Kobe on the 29th. The first elements of the Attack Force were scheduled to sail on 9 September. D-Day was only 20 days away.

But the Amphibious Group’s studies of Inchon provided a basis for planning, the Marine Division staff had already moved aboard Mount McKinley, and with the arrival of the commander of the joint force decisions could be made.

With no time for rehearsal, with only the minimum time for combat loading, Joint Task Force 7 was responsible for the execution of an extremely audacious plan. Far larger forces had been committed to far smaller objectives during the war against Japan: at Iwo three divisions had been employed and at Okinawa four; and while the opposition on those islands was of course far stronger than that anticipated at Inchon, naval strength had made it possible to isolate the objective and to deny the enemy all hope of reinforcement. At Inchon some measure of isolation of the battlefield was indeed possible, as a result of command of the sea and air and of the effort previously expended in the knocking down of bridges. But while trains and ships and even trucks might be excluded, there was no guarantee that large numbers of unfriendly pedestrians might not be concentrated by night marches against the beachhead.

Eighty years earlier Admiral Rodgers had estimated that 5,000 troops would suffice to capture a treaty. Since then things had changed. Where formerly the only signs of habitation had been the scattered fishing huts of Chemulpo there had now developed a sizable city, while the events of the preceding weeks had sufficiently demonstrated that the enemy had modernized his military techniques. The task of the 1st Marine Division, which with attached Army and Korean units would reach a D-Day strength of 25,000, was to land in and capture a city with a population of some 250,000 souls, and then advance without loss of momentum to seize Kimpo airfield, 12 miles inland, by D plus 2. The area involved was roughly comparable to that of Saipan, where three divisions had been committed to the attack with another held in reserve, where there were no great cities, where hydrographic difficulties were slight, and where the flanks of the assault force were protected by the vastness of the Pacific Ocean and the power of the Pacific Fleet.

Reinforced, beginning on D plus 2, until it would attain a strength of almost 70,000, X Corps was to press onward to capture Seoul, capital and largest city of the country, and then hold until contact was made with Eighth Army forces coming up from the southward. How long this would take was problematical in view of the great depth of the turning movement. The distance between the point of landing and the beleaguered forces in the perimeter was some 140 miles airline, roughly comparable to that from Philadelphia to Washington, more than twice that at Anzio beachhead where the link-up took four months.

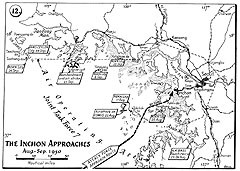

Although the risks inherent in the introduction of so small a force into so large a land mass at so great a distance from supporting units could perhaps be discounted, given the wear and tear inflicted on the North Korean People’s Army and its commitment far to the south, the Inchon landing still presented some appalling tactical problems for the naval forces which had to bring it off. These difficulties stemmed principally from the extraordinary hydrography of the objective region and from the configuration of Inchon harbor. Shallow water at Inchon limited the date of a possible attack to a short three-day period each month; the rise and fall of the tide limited the time of attack to two short periods each day; the narrow and tortuous entrance channels restricted the movement of shipping for the last 34 miles of the approach, made daylight entry almost imperative for vessels of low power and poor maneuverability such as transport, cargo, and LST types, and prevented the normal night retirement of amphibious shipping from the objective area.

These hydrographic conditions had limited the development of this Korean Piraeus. Although the second port of South Korea, Inchon’s ability to sustain an army corps was marginal. The navigational hazards of the approach and the tidal silting which had bordered the city with drying mud flats had kept its cargo handling capacity small: where Pusan could handle 25,000 tons a day, Inchon could manage less than half of that. Piers were lacking, and the five berths in the tidal basin compared unfavorably with the 30 alongside berths at Pusan. Nor was the outer anchorage of a sort that could conveniently accommodate an invasion armada: at Inchon this measures about seven miles from north to south and a mile or less from east to west. Only some 50 ships can anchor here; a tidal current of two to three knots sets in and out along the long axis.

Yet before the problems of post-assault logistics could be faced, some means had to be found to get the troops ashore. This too was difficult: not only did the lack of maneuvering room within the harbor complicate the ship-to-shore movement and restrict the possibilities of the fire support ships, but there was a notable absence of suitable assault landing points.

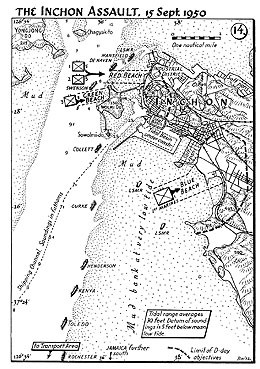

Of these only two could be found which were in any sense adequate, Blue Beach in the southeastern section of the city and Red Beach on its western shore, and they could be called beaches only by courtesy. Located at opposite ends of the town, they were separated by a four-mile water distance; lined with piers and seawalls, their assault required scaling ladders; reentrant in contour, they were subject to enfilading fire. Nor was this the sum of the difficulties, for from between these landing points there protruded from the Inchon waterfront a causeway leading to the small island of Wolmi Do, known anciently as Isle Roze in commemoration of the French admiral whose unsuccessful assault on the forts marked the first arrival of western civilization. This island, which with its smaller satellite Sowolmi dominated and divided the Inchon outer anchorage, was known to have been fortified by the Communist invaders. Before an assault into the city could be contemplated its capture was essential.

The necessity of first reducing this strong point and the constricted nature of the entrance channels ruled out a night approach by the transport groups and eliminated the possibility of surprise. Since an attack in two phases was required, it was decided to send a small force in on the morning tide to seize Wolmi Do and then, after the waters had receded and risen again, to bring in the main part of the Attack Force for a late afternoon assault into the city. Nor was the warning to the enemy limited to this intertidal period. The need for pre-invasion bombardment of Wolmi’s fortifications, which would extend the alert period, reemphasized the fact that the attack was being directed not against an isolated island but against an area which could be reinforced.

The final impact of the Inchon tides appeared in the planning for logistic support. Only small craft could negotiate Blue Beach at the southern edge of the city; only at Red Beach in the north and at Green Beach on Wolmi Do could LSTs be brought in, and there only during the high tides between D-Day and D plus 2. At low tide nothing could be landed, and behind its ramparts of yielding ooze the city lay secure. To supply the assault forces during the night of D-Day, it was decided to run LSTs ashore at Red Beach and leave them through the inter-tidal interval, accepting the possible loss of these vessels in the interests of adequate troop support. For the LSTs, high and dry and with cargoes composed largely of explosive and inflammable materials, the prospect was not enviable, but a scheme of maneuver was worked out which emphasized the fastest possible clearing of Red Beach in order to ensure, so far as possible, the survival of these ungainly vehicles and of their priceless contents.

Such were the known generalities of the situation, but again, despite American occupation of Korea, intelligence was lacking and the specifics were unknown. Would the mud banks of Inchon support tracked vehicles? The answer was available in Rodgers’ report of 80 years before, but this was safely filed in the National Archives and no recent information was at hand. How high were the seawalls? What were their implications for the lowering of ramps of landing craft, or for troops attempting to get ashore? Would scaling ladders in fact be necessary? Which piers, if any, would support heavy vehicular traffic? In the effort to acquire reliable information Army personnel who had served in Inchon were rounded up and quizzed, photographic missions were laid on, the Air Force flew some photo interpreters out from the United States, and on 1 September a naval officer, Lieutenant Eugene F. Clark, was put ashore with two interpreters, a radio, and some small arms on the friendly-held island of Yonghung Do, 15 miles below Inchon.

In the meantime, and on the basis of such intelligence as was available, the work of the planners continued. On his arrival in Tokyo Admiral Struble was briefed by Doyle’s staff on the problems of Inchon, issued orders for concurrent planning, and undertook to give oral decisions as needed as the work went on. The flagship Rochester, on her arrival, was berthed alongside Mount McKinley to keep the staffs in close proximity. On the 30th Andrewes, Ruble, Higgins, and Austin flew up from Sasebo for a conference of prospective task force commanders. And while the planning proceeded the preliminary operations were begun: new operating areas and operating schedules, intended to ensure adequate preparation of the objective without an overconcentration which would alert the enemy, were made up by Struble’s staff for broadcast by ComNavFE to the carrier forces at sea.

So the concept of the operation took form. In early September, and again in the days preceding the landing, the three carrier units of Joint Task Force 7—Admiral Ewen’s fast carriers, Admiral Ruble’s escort carriers, and the British light carrier Triumph—would work over the west coast with their efforts gradually converging toward Inchon. Prior to D-Day a destroyer and cruiser bombardment of Wolmi Do would be carried out. On the early morning tide of 15 September a battalion landing team of the 5th Marines would assault Wolmi in order to secure that commanding position. On the afternoon tide, at about 1700, the main attack into the city would be carried out by the 5th Marines’ remaining two battalions and by the 1st Marines. While the two Marine regiments moved rapidly to expand their holdings to Kimpo airfield and the Han River line, the 7th Infantry Division (Reinforced) and corps troops would be landed administratively and would then operate as ordered by the corps commander. Throughout the operation bombardment and fire support would be provided by cruisers and destroyers, and air cover, air strikes, and close support by carrier aviation. So far as the air was concerned Joint Task Force 7 was self-sufficient: complications of coordination or control during the landing phase were fended off by the proviso that except at the request of Admiral Struble no FEAF aircraft would operate in the objective area subsequent to D minus 3, while for the later stages of the campaign X Corps was provided with its own Tactical Air Command, composed of Marine aircraft and commanded by a Marine brigadier general.

Such was the plan for the operation as worked out by the staffs of Seventh Fleet, the Amphibious Group, and the Marine Division. For Inchon, as for Pohang, the planning was necessarily carried out in violation of all the rules and in record time. By 2 September, when the Joint Task Force operation plan and the Amphibious Group’s operation order were issued, Marine planning was nearing completion, and on the next day Admiral Doyle and General Smith sailed in Mount McKinley for Kobe, where the bulk of the Marine Division had just arrived from the United States.

This speed in planning, essential as it was, also brought its problems. There was no time for joint training, no possibility of rehearsal. Division and Attack Force staffs had to plan for lower echelons without benefit of comment or opinion from the subordinates, and completed plans made their appearance as hand-outs to the regimental and task unit commanders involved. The risks of high speed concurrent planning for so complex an enterprise were illustrated by difficulties in shipping allocation: owing to lack of information on the characteristics of available vessels, the 34 transport and cargo types which MSTS WestPac had been requested to nominate for the invasion turned out to be too few, and on 9 September, D minus 6, Captain Junker was called upon for a further 11 ships. Yet despite the necessarily authoritarian nature of the procedure, and the pressures under which it was carried out, there were few mistakes. On 7 September Admiral Struble flew to Sasebo and Kobe to confer with his principal subordinates and to tidy up loose ends. The most important of these, an overly ambitious commitment of the fast carrier air effort, was rectified in the 40-minute briefing which was all that could be given Admiral Ewen on his part in the operation.

Table 9.—JOINT TASK FORCE 7: INCHON

[Complete listing of the ships and naval forces involved under construction]

| JOINT TASK FORCE 7. | VADM Arthur Dewey Struble, USN |

| Task Force 90 (TF 90) Attack Force 1-2 AGC, 1 AH, 1 AM, 6 AMS, 3 APD, 1 ARL, 1 ARS, 1 ATF, 2 CVE, 2 CA, 3 CL (1 USN, 2 RN), 1 DE, 12 DD, 5 LSD, 3 LSMR, 4 ROKN PC, 1 PCEC, 8 PF (3 USN, 2 RN, 2 RNZN, 1 French), 7 ROKN YMS, 47 LST (30 Scajap), plus transports, cargo ships, etc., to a total of approximately 180. |

RADM James Henry Doyle, USN |

| Task Force 91. Blockade and Covering Force. 1 CVL, 1 CL, 8 DD. |

RADM SIR William G. Andrewes, RN. |

| Task Force 92. X Corps 1st Marine Division, Reinforced; 7th Infantry Division, Reinforced; Corps Troops. |

MGEN Edward. M. ALMOND, USA. |

| Task Force 99. Patrol and Reconnaissance Force 2 AV, 1 AVP, 3 USN and 2 RAF Patrol Squadrons. |

RADM Geroge. R. Henderson, USN. |

| Task Force 77. Fast Carrier Force 2-3 CV, I CL, 14 DD. |

RADM Edward C. Ewen, USN |

| Task Force 79. Logistic Support Force 2 AD, 1 AE, 2 AF, 1 AK, 3 AKA, 3 AKL, 4 AO, 1 AOG, 1 ARG, 1 ARH, 1 ARS, 1 ATF. |

Although two divisions were a small force with which to enter a large enemy-controlled land mass, the Inchon landing was nevertheless an operation of a certain magnitude. To transport, protect, and put ashore a force of this size calls for a considerable investment in shipping and in personnel, and "Chromite," despite the expected absence of air and sea opposition, placed a heavy load upon the Navy. The total strength of Joint Task Force 7 amounted to some 230 ships of all shapes and sizes, from APDs of 2,100 tons full load displacement to transports of ten times that size. Except for a few gunnery ships held back to support the flanks of the perimeter, it included all combatant units available in the Far East. Fifty-two ships were assigned to the Fast Carrier, Patrol and Reconnaissance, and Logistic Task Forces; the remainder went to make up the Attack Force, Task Force 90, under Admiral Doyle. Of these, more than 120 were required to lift X Corps, while the rest were involved in gunfire and air support, screening, minesweeping, and miscellaneous other duties.

That so sizable an amphibious lift could be so rapidly assembled was remarkable, the more so in view of the preexisting policies of economy and of down-grading the amphibious function. In 1945 the assembly of such a force would have seemed simple enough; by 1952 it would have become quite feasible; but 1950, the year that it was needed, was the year of the drought. Inevitably, therefore, the armada that eventuated was a somewhat heterogeneous one, and of the 120-odd units assigned to lift X Corps less than half were commissioned vessels of the U.S. Navy. Thirty of the LSTs assigned the operation were Scajap ships, manned by the hardworking and loyal enemy aliens, and, of the vessels collected by MSTS WestPac, 13 were MSTS-owned, 26 were American cargo ships on time charter, and four were chartered Japanese Marus.

With completion of the planning phase, a stage in the operation had ended. Shipping was available, and a movement schedule had been worked out to lift X Corps to the objective area; a scheme of maneuver had been developed to overcome the natural difficulties of Inchon; supporting forces were on hand to deal with foreseeable contingencies. One minute after midnight on 11 September the Joint Task Force 7 plan was placed in effect for operations. Some of the slower shipping had already set sail.

But any military plan is based on certain assumptions, and "Chromite" was no exception. Underlying the basic concept were not only the postulates that phases one and two of the Korean campaign would be completed, but also that there would be no important change in the disposition of enemy forces, and that the greater portion of the invading army would remain committed to the Pusan perimeter. That this should be the case was fundamental to CincFE’s plan, which could be described in the words of Wee Willie Keeler as to "hit ‘em where they ain’t," or in the more martial analogy employed by General MacArthur himself, to follow the example of Wolfe in his approach to the Plains of Abraham.

By early September these assumptions appeared to have been fulfilled. The perimeter was holding, Eighth Army had been reinforced, and the North Korean People’s Army was deep in South Korea. Large and effective though this force had proven itself to be, it possessed the defects of its virtues. Chief of these was an inflexibility in the realm of movement and logistics, which had by now been greatly accentuated by the effect of air and naval attacks on the Communist supply lines. The North Koreans could still push hard against the perimeter, but the problems of rapid and flexible redeployment were almost insuperable.

Last and in some ways most important of CincFE’s assumptions was the postulate that the enemy would receive no important reinforcement. In Korea the intervention of the United Nations had wholly changed the strategic picture, and had first delayed and then threatened with frustration a campaign planned as a walk-over. The assumptions of the invader had already proven false, and agonizing reappraisal had been thrust upon the planners in North Korea, and in the regions beyond the Yalu and the Tumen. To press on with the offensive, in the hope of driving the U.N. armies into the sea before the situation could be stabilized, had been the natural first reaction. But the arrival of important naval forces and the known amphibious capabilities of the U.S. Navy must necessarily have raised the specter of a landing in the rear, forced a review of the situation, and emphasized the desirability of further assistance from the Communist elder brothers.

There was thus at least a possibility that these, in their turn, would raise the struggle to a higher level, by providing the North Koreans with ground reinforcements, or with air or submarine strength. As regards the former, however, Russian ground intervention seemed hardly probable, while the concentration of Chinese Communist Forces opposite Formosa had left them poorly deployed for rapid action. And while air and submarine strength was available in quantity in the Soviet Maritime Provinces, its employment was fairly plainly fraught with risk. In the air, perhaps, the Far East Command’s air and naval contingents could have withstood a Communist offensive, but with regard to undersea warfare the situation was very different. Given the length of the seaborne supply line and the shortage of escort vessels, a serious submarine offensive would have faced the United States with a choice of accepting defeat or resorting to high-yield weapons. Quite possibly this situation was appreciated by the other side.

Since no such step was taken by the Communists, this problem was not posed, and CincFE’s assumptions were almost totally borne out. The enemy offensive was not weakened to guard against an amphibious counterstroke; although the Chinese had begun a northward redeployment, no ground reinforcements were provided the North Koreans; no aerial or undersea auxiliaries made their appearance. But on a lower level, and unknown to the U.N. commanders, a rapid reaction had already taken place in the form of a minelaying campaign designed to threaten U.N. naval forces and make Korean coastal waters untenable.

As early as 10 July shipments of mines were rolling southward down the east coast railway from the Vladivostok region. One week later Soviet naval personnel had reached Wonsan and Chinnampo and were holding mine school for their North Korean friends. This reaction, which wholly justified Admiral Joy’s concern with the northeastern railroad route, was sufficiently rapid to get the mines through before the limited Seventh Fleet and NavFE forces could be brought to bear. Some 4,000 mines were quickly passed through Wonsan, and by 1 August mining had been begun at that port and at Chinnampo. In time Russian naval officers ventured as far south as Inchon, shipments of mines were trucked down from Chinnampo to Haeju, and before the bridges were knocked down consignments had reached Inchon, Kunsan, and Mokpo by train.

This effort to counteract U.N. control of the sea went undetected. In mid-August search planes had reported enemy barges and patrol craft at Wonsan and Chinnampo, but while in retrospect these were believed to have been engaged in minelaying, the intelligence was not so interpreted at the time. The operation plans of ComNavFE, Commander Seventh Fleet, and Commander Attack Force, while crediting the enemy with limited mining capabilities at Inchon, stated that available information indicated no mine-fields in that area.

Part 2. 15 August–21 September: North to Inchon

While "Chromite" was still in preparation the return to the north had begun. Although heavily engaged along the coast and busy with refugee evacuation, the ROK Navy had been able to mount offensive operations. Commander Luosey, who as CTG 96.7 operated this inshore fleet, was not privy to the Inchon planning, but the basic strategic situation was as clear to those in Pusan as it was to those in Tokyo, and the increasing probability that the perimeter would be held emphasized the value of deep flanking positions, whether for raids, landings, or the infiltration of agents. On 15 August, therefore, CTG 96.7 advised ComNavFE of his intention, if not otherwise directed, of seizing the Tokchok Islands in the Inchon approaches as a base for intelligence activities and future operations.

No countermanding instructions were received, help was promised by the west coast Commonwealth units, and on the 17th Operation Lee, named for the commanding officer of PC 702, was begun. With two YMS in company Lee put a Tioman force ashore on Tokchok To; on the next day Athabaskan turned up to support the effort and the island was secured. On the 19th Lee’s force landed on Yonghung Do, in the Inchon approach channel, and in the days that followed expanded its control to other islands in the west coast bight. On the 20th a landing party from Athabaskan destroyed the radio gear in the lighthouse on Palmi Do at the mouth of Inchon harbor. By 1 September, when Lieutenant Clark arrived at Yonghung Do, considerable information concerning the defenses of Inchon had been collected by intelligence teams under Lieutenant Commander Ham Myong Su, ROKN. And reports from the British indicated that the seizure of Yonghung Do had caused the enemy to shift forces southward to guard against a possible mainland landing.

So far, so good, but on 1 September, as the invasion plans were moving to completion, there came the enemy’s last and greatest effort to crush the Korean beachhead. In this hour of crisis Eighth Army needed all the help that it could get, and again phase one threatened to interfere with phase three. Not only did enemy pressure bring emergency calls for the retention of Task Force 77 in close support; it also threatened to make the Marine Brigade unavailable for the Inchon landing. Previous orders to release the brigade on 4 September were cancelled on the 1st, and for the second time the Marines were committed to the Naktong front.

Faced with the danger that EUSAK’s needs might prevent the release of the brigade, General Almond proposed to replace it at Inchon by a regiment of the 7th Division. To the Navy and Marine commanders the assignment of this unit, untrained in amphibious operations and with a large infusion of South Korean recruits, would force abandonment of the two-beach assault for one in which the infantry would be landed in column behind the 1st Marines, with all the implications that this might have for the success of the operation. But the issue was fortunately resolved by Admiral Struble who, while insisting on the release of the brigade, observed that Eighth Army’s need for a reserve could be met by embarking a regiment of the 7th Division and moving it to Pusan, where it could be either landed in support of the perimeter or sailed to rejoin its parent organization at Inchon.

On this basis it was settled. Release of the brigade was rescheduled for evening of the 5th. The requests for Task Force 77 were turned down by ComNavFE. For all of its magnitude the Communist offensive had succeeded neither in breaking the perimeter nor in diverting important forces from the impending counterstroke.

Although the fast carriers had withdrawn to Sasebo on 5 September, following the strikes against the Pyongyang area, naval activity continued along Korea’s western shore. Between Kunsan and the 38th parallel, aircraft from Triumph and Badoeng Strait scoured the land, concentrating on railroad bridges, rolling stock, and electrical transformer stations. While continuing to interdict coastal traffic, Admiral Andrewes’ surface ships found opportunity to bombard Inchon on the 5th and Kunsan the next day. On the 7th, Triumph departed to the east coast for two days of operations off Wonsan, but with the arrival of Sicily on the 8th two-carrier operations were resumed. On the 10th, the last day on station prior to departure for replenishment, Admiral Ruble’s Marine squadrons were ordered to burn off the western half of Wolmi Do. Double loads of napalm, to a total of 95,000 pounds, were ferried in during the course of the day, with resultant destruction of 90 percent of the top cover in the designated area, and presumable discouragement of the garrison.

It might be thought that an attack of such unprecedented nature against a terrain feature of such localized strategic importance would have alerted the enemy to what was in prospect and given him five days for emergency redeployment. Perhaps it did, but his capabilities in this direction were limited, and in any case the larger security picture for the Inchon landing was problematical at best. In Japan, where there were plenty of enemy agents and no censorship, the situation was a highly compromising one, and the arrival of the Marines and the assembly and loading of troops were matters of common knowledge.

Some efforts to delude the Communists were indeed carried out. Triumph was briefly shifted to the east coast. After dropping a bridge on the 9th at Kanggu Hang, below Yongdok, Helena and her destroyers ran north to 40 degrees to shoot up shipping and trenches at the island of Mayang Do. At Pusan the Marine Brigade was lined up and given a semi-public lecture on the hydrography of Kunsan; after replenishment at Sasebo, Triumph would concentrate her efforts in the vicinity of that port, as would the Fifth Air Force; in this region, where Bass’ earlier beach survey had been detected by the enemy, a raid was scheduled by an Anglo-American force embarked in HMS Whitesand Bay. But the basic cover and deception appears to have been accomplished by CincFE himself, by his insistence on so improbable an objective and by his pressure for speed. The enemy, it would seem, concurred in the views of those who questioned the depth of the turning movement and the hydrography of Inchon. South of 38 parallel the heaviest days of his mining effort were at Mokpo and Kusan on the west coast, and in the neighborhood of Chumunjin in the east. At Inchon the effort was too little and too late.

In Japan, meanwhile, the skill and devotion of the implementers had succeeded within the allotted time in matching the vision of the strategist. While Wolmi Do was burning on the10th the slower elements of the Attack Force were getting underway. A portion of the pontoon movement group, with gear for the expansion of Inchon’s port facilities, had already departed Yokohama, as had the rocket ships which would bombard the beaches. The tractor movement elements of LSTs and accompanying ships were getting underway from Kobe. At Kobe, at Sasebo, and at Pusan, the transports were preparing to set sail in accordance with the movement schedule. Shipping from Yokohama and Kobe would pass south around Kyushu and then steer to the northwest, to be joined south of Cheju Do by units from Sasebo and Pusan. Passing through predetermined points at predetermined intervals, the pieces that made up Task Force 90 would be reordered and reshuffled, moved onward into the Yellow Sea, and funneled into the Inchon approaches according to a rigidly determined plan. Once begun, so elaborate an operation is difficult to postpone or modify, and at Inchon the tides forbade delay. No delay, it is true, was anticipated from hostile action, and in any case precautions against such interruptions had been taken. What could not, however, be planned for was the hostility of the elements.

From a meteorological point of view, a war in Korea presents a problem to the maritime power, for most of the peninsula’s weather is manufactured over the continental land mass. Yet there is some compensation in the fact that the typhoons which afflict the area, and which provide the greatest single threat to military operations, are of oceanic birth, and can be tracked in their passage northwestward from the Marianas. Their season, which begins in June and extends to mid-September, had thus far precisely coincided with the war. Grace, who had caused some difficulties at the time of the Pohang landing, had been followed by two milder sisters, but September brought more trouble. On the 3rd, Jane had forced the evacuation of patrol squadrons from Japan to Okinawa, and had slashed through Kobe bringing gusts of up to io knots, damaging ships and gear assigned to the Marine Division, taking a full day from an already tight loading schedule, and depriving the brigade of air support from Ashiya. One week later, as the Attack Force was preparing to sortie, Kezia was reported moving up from the Marianas, with a predicted arrival in Tsushima Strait on the 12th or 13th, just as the amphibious shipping was scheduled to cross her path.

Since the loss of the Duke of Medina Sidonia’s Armada, the influence of weather on great naval operations has profoundly affected the history of the west; in the Orient an equally illustrious precedent is provided by the Kamikaze, the Divine Wind of 1281, which threw back the second Mongol invasion of Japan. That modern fleets are also vulnerable to such hazards was made evident in the Second World War: in the invasion of North Africa Admiral Hewitt had to balance advice from his force meteorologist against pessimistic reports from afar; the landings in Sicily were complicated by weather; "Overlord" itself had to be postponed; and two typhoons caused serious trouble for Admiral Halsey’s Third Fleet. Now the same question faced Admiral Struble, and in even more excruciating form: Admiral Hewitt had been provided with alternative invasion beaches inside the Mediterranean, but here there were no alternatives; General Eisenhower had been able to put off "Overlord," but the Inchon tides permitted no postponement. On the assumption, perhaps better on the hope, that the storm would recurve, Struble ordered the assault shipping out of Kobe a day ahead of schedule, and in the early morning darkness of the 11th sortied in Rochester from Yokosuka. Later in the morning Admiral Doyle sailed from Kobe in Mount McKinley and headed southwestward for Van Diemen Strait. In the evening, while passing east of Kyushu in heavy seas, Doyle learned that the Transport Group had reversed course to the eastward; this was promptly countermarched again in order to outrun the storm, while Mount McKinley headed for Sasebo to pick up CincFE and the other GHQ spectators. Prospects were still unclear, however, for on the morning of the 12th the light cruiser Manchester, proceeding singly from the United States, located the typhoon center 150 miles south of Kyushu, and radar tracking showed it moving at seven knots in the direction of the Yellow Sea. But fortune favored the brave. Kezia did indeed recurve, and by the time she passed over the southeast corner of Kyushu on the afternoon of the 13th the Attack Force was well clear.

The departure of the escort carriers after the burning of Wolmi Do had left the waters off Inchon tenanted only by Commonwealth and ROK blockading forces, and by a single patrol plane which, being relieved on station, maintained 24-hour supervision of the Yellow Sea. But the ROK Navy remained busy: Operation Lee was continuing; PC 703 sank a mine-laying sailboat off Haeju on the 10th, and on the 12th got three more small craft in the Inchon approaches. And now, as the Attack Force plowed forward through heavy seas and the Marines in the troop compartments cursed their fates, the tempo of operations in the objective area began to increase.

Even here Kezia had made herself felt, for the Japan-based patrol planes had been evacuated to Okinawa, and where plans called for increased antisubmarine search around the approaching Attack Force, no such sorties could in fact be flown. But the 12th, D minus 3, saw Task Force 77 back at work in the Yellow Sea, operating in an area 120 miles west by south of Inchon. On the 12th and 13th strikes designed to seal off the objective area were flown against ground installations and lines of communication in Area O, while the jets swept airfields to the northward. On the 13th, D minus 2, a special combat air patrol was provided for the Wolmi Do bombardment group.

On the 14th, as Transport and Tractor Groups were approaching the objective and as the bombardment of Wolmi Do continued, carrier-borne aircraft were in operation and on call along the entire western coast of South Korea. Triumph was working over the Kunsan region while maintaining four fighters ready for immediate launching as combat air patrol for transports south of 36 degrees. Carrier Division 15 was back on station, and in addition to keeping fighters on call to cover shipping north of 36 degrees was providing spotting aircraft and combat air patrol for the Wolmi Do bombardment ships. From the middle of the Yellow Sea the fast carriers maintained a tactical air coordinator over the Inchon area from dawn to dusk, and provided him with three strikes, morning, midday, and afternoon, of 16 ADs apiece.

The little island of Wolmi Do, the object of much of this solicitude, forms an equilateral triangle slightly more than half a mile on a side, with its eastern edge running north and south, and with a spit extending from the northern corner. From the base of the spit a 900-yard causeway leads northeastward to the Inchon shore; from the western corner another of roughly equal length runs southward to the islet of Sowolmi. Wolmi Do was known to be defended by enemy artillery, and was thought to be heavily so. Although much of the top cover had been burned off by the Marine pilots of Cardiv 15, and although very considerable air strength was available to support the assault, preparation by naval gunfire was deemed essential.

If the war in the Pacific had demonstrated anything, it was the virtue of naval gunfire in preparation for an assault against a defended objective. Given the nature of Japanese island fortifications, no substitute existed for slow, deliberate, aimed fire directed at specific targets and delivered at short-range, and from Tarawa on progress in this technique was notable. So far as the assault troops were concerned, the longer the preparation the better, but in any given operation the time available for such preliminaries was subject to various and often conflicting considerations. At Inchon this was again the case: in view of the mainland nature of the objective it was at least possible that more time in preparation would mean more resistance subsequent to landing. A preliminary decision for a single day of effort was followed by further discussion among the parties concerned, and on the 10th Struble modified his operation plan by dispatch. Bombardment would commence on D minus 2, and would be repeated the next day if necessary.

The operation plan assigned the responsibility for this bombardment to Admiral Higgins’ Gunfire Support Group, Task Group 90.6; the narrow waters of Inchon harbor placed the main burden on Captain Allan’s destroyers. Hydrographic conditions also led to the decision to come in with the flooding tide and anchor, so that the ships would lie head to sea during the bombardment, and retirement in the event of damage would be simplified. At 0700 on the 13th the destroyers started up the channel in column, Mansfield in the lead, followed by De Haven, Swenson, Collett, Gurke, and Henderson. Behind the destroyers came the cruisers: Rochester with Admiral Struble embarked, Toledo with Admiral Higgins, Jamaica, and Kenya. Overhead there orbited a combat air patrol from Task Force 77, while to seaward that force was preparing to launch a strike which would hit the island shortly before the arrival of the destroyers. At 1010 the Support Group entered the approaches to Inchon outer harbor.

The decision to come in on the flooding tide proved advantageous in more ways than one, for at 1145 a string of watching mines was sighted off the port bow, in the area from which the British cruisers had bombarded the port ten days before. Here was a threat for which the bombardment group was ill-prepared. Tbe first positive mine sightings had been made on 4 September, southwest of Chinnampo, by the destroyer McKean; three days later British units heading north through these same waters had encountered many floaters; on the10th the Korean PC 703 had sunk a mine-layer off Haeju and had reported that the mouth of Haeju Man had been mined. In Tokyo, on that same day, Admiral Struble had discussed the mine problem with CincFE: if contact mines had been placed in the Inchon approaches, it was the opinion of Commander Joint Task Force 7 that the Attack Force could be pushed through; if the approaches had been salted with modern influence mines the situation was more doubtful; all that could be done was to go on up and see. A conference with ComNavFE led to a recommendation to CincPacFleet for the earliest possible reactivation of more AMS; on the next day Admiral Radford passed this request to CNO and himself started additional sweepers to the Far East.

But reinforcements would be long in arriving, the invasion had to go forward, no sweep had been planned, and the seven minesweepers present in the theater were two days astern with the Transport Group. Before nightfall they would be ordered to the objective area at best speed, but for the moment the best that could be done was to make do. There might be more mines further up the channel; there was no way of knowing. Henderson, the tail end destroyer, was detached to sink as many as she could by gunfire before the tide covered them, and the other destroyers continued on toward Wolmi Do.

It was just past noon, and the air strike was still on, as Mansfield and her followers moved through the harbor to their assigned positions, some less than half a mile from the fortified island. Anchoring at short stay, the ships swung around to head southward, into the flooding current, and trained their batteries out to port. There was boat traffic in the harbor, activity in the city was visible, but on Wolmi Do there was no sign of life.

Shortly before 1300 the five destroyers commenced deliberate fire on the island’s batteries and on the Inchon waterfront. Some minutes of undisturbed bombardment followed, and then the enemy batteries opened up. Communist fire was concentrated on Swenson, Collett, and Gurke, the ships nearest the island, and in the course of the next 20 minutes scored on all three. Collett received the heaviest damage, taking nine 75-millimeter hits, one of which disabled her computer and forced her to fire in local control. Three hits were made on Gurke; a near miss killed an officer on Swenson; total casualties were one killed and five wounded. For nearly an hour the engagement continued until at 1347, after the expenditure of about a thousand 5-inch shells, the destroyers weighed and proceeded down channel. Five minutes later the cruisers opened from the lower harbor against the Wolmi batteries, and with one intermission for an air strike continued shooting until 1640, when the task group retired seaward.

The bombardment had been a destructive one. On the other hand the enemy had been alerted: during the day U.N. headquarters had intercepted a North Korean dispatch which reported the bombing of Wolmi Do, the approach of naval vessels, and "every indication that the enemy will perform a landing." The response of Wolmi’s defenders had been vigorous, and the island’s gunners were still firing as the destroyers departed. For Captain Allan’s ships this persistent opposition merely implied another trip in next day for a repeat performance, but for some in the higher echelons news of the enemy reaction proved unsettling. On board the command ship Mount McKinley, now steaming northward through the Yellow Sea, one highly placed observer noted that among those who had counted on an unopposed or lightly opposed landing "a certain measure of pessimism appeared."

Up front, however, the problems were problems of detail. In the evening Higgins and Allan went aboard Rochester for a conference with Admiral Struble. The decision was taken to do it again the next day. Collett was detached because of her damage, and told off along with the tug Mataco to finish the destruction of the mines. Some crystal trouble with aircraft radios, which had made difficulties for air spotting and air coordination, was dealt with by a change in the frequency plan. Otherwise all was routine, and in the morning the other four destroyers, joined by Henderson and supported by the cruisers, again filed up the channel.

At 1050, as an air strike against the Wolmi Do and Inchon gun emplacements was beginning, the cruisers anchored in the lower bombardment area. Twenty minutes later they commenced firing on Wolmi Do, and shortly after noon the destroyers were deployed to their anchorages in Inchon harbor. There, following another air strike, they began their pointblank bombardment of the island, firing from 1255 to 1422, and expending some 1,700 rounds. Another strike from Task Force 77 came in as the destroyers moved down channel; for another hour the cruisers continued their work. Enemy fire, this time, was late, sparse, and inaccurate, and no ship was hit. Air spotting had been considerably improved, and the itemized claims of destruction and damage inflicted by the two-day effort were encouraging. Together with the work of Task Force 77, the gunfire appeared to have done the job. Wolmi Do was ready for the Marines.

Two approaches from the Yellow Sea lead inward to Inchon, So Sudo or Flying Fish Channel to the westward, and Tong Sudo or East Channel close inshore. Although its currents are the stronger, reaching four and a half knots on a rising tide and almost seven on the ebb, So Sudo offers fewer hazards to navigation, and had been selected as the route of approach for the Attack Force. Shortly after midnight on the 15th the Gunfire Support Group again entered So Sudo and headed north, accompanied this time by the Advance Attack Group, Captain Norman W. Sears, with the 3rd BLT, 5th Marines, embarked. Following the destroyers came the LSD Fort Marion, with three tank-loaded LSUs in her capacious maw, and the fast transports Bass, Diachenko, and Wantuck; the cruisers, now joined by Mount McKinley, again brought up the rear.

As the ships coasted in on the flooding tide, navigating by radar up the tortuous passageway, the light at the harbor’s mouth went on: having found the beacon on Palmi Do still operative, Lieutenant Clark had heeded the Oriental proverb that it is better to light a candle than to curse the darkness. Offshore in the pre-dawn gloom, Task Force 77 flew off the first of the combat air patrols, barrier patrols, and deep-support strikes which it was to provide throughout the day, while Admiral Ruble’s group launched ten Corsairs for the pre-landing attack on Wolmi Do. The gunfire spotter, the combat air patrol, and the deep support group were all on station by 0528, when the first strike group reported in to the Air Direction Center in Mount McKinley.

By this time the Advance Attack Group had reached its destination in Inchon inner harbor, and Wolmi, no longer a menace, was put to constructive use: anchoring with the island between them and the city’s shore batteries, Captain Sears’ ships were able to boat their troops undisturbed. The signal "Land the Landing Force" was executed at 0540, and by 0600 the assault troops had been embarked and the landing craft were circling while awaiting the coming of L-Hour. High overhead the leader of the first air strike rolled his plane over and started down.

L-Hour, set for 0630, was preceded by 45 minutes of bombardment. To the north of Wolmi Do Mansfield, De Haven, and Swenson fired on the island and on the northern shore of Inchon; south of the island Collett, Gurke, and Henderson concentrated on Wolmi, Sowolmi, and on the city’s southern shore. From the southern fire support area Toledo and Kenya divided their efforts between northern Inchon and the Blue Beach area, while Rochester and Jamaica took the region behind Blue Beach and on the right flank. Any enemy reaction at the Inchon end of the Wolmi Do causeway would be dealt with by De Haven and Collett, who were assigned to cover this region with VT-fused ammunition.

While the bombardment continued Marine Corsairs from the escort carriers bombed and rocketed the island. At 0615, L minus 15, the three rocket ships, each with an allowance of 1,000 5-inch spin-stabilized rockets, moved past Green Beach on Wolmi’s northern tip and let go. At 0628, as the three LSMRs moved clear, the first wave of landing craft crossed the line of departure and headed in, while the cruisers and two of the destroyers ceased fire to permit the pre-landing beach strafe by the Corsairs.

At 0633 the first troops were ashore in a scene of smoke, dust, and devastation, and were moving forward against negligible resistance. Thirteen minutes after the first wave had touched down, the three LSUs from Fort Marion reached the beach with supplies for the assault force, and began to disgorge their ten tanks. Thirty minutes after the initial landing the northern half of the island was controlled by the Marines.

Admiral Struble was just going over the side for a small boat reconnaissance of the situation when a visual signal was received: "The Navy and the Marines have never shone more brightly than this morning. MacArthur." Pausing only to relay the message to the fleet, the force commander boarded his boat, stopped by at Mount McKinley to pick up CincFE, and proceeded into the inner harbor to survey Wolmi Do. The day was warm and pleasant, everything was going well, no action was needed. By 0807 the dominating heights on Wolmi had been secured; before mid-day Sowolmi had been assaulted across the narrow causeway and had been taken with the aid of an air strike from the orbiting Corsairs. Total Marine casualties were 17 wounded; the small price paid for this essential objective, with its 400-man garrison and its fairly elaborate system of defensive works and armament, reflects the effectiveness of the advance preparation.

By noon, then, the objective had been secured and fighting had ceased. By noon, too, the waters had receded. On Wolmi Do, in the September sunshine, the Marines gazed across the half-mile causeway and the inudflats toward the silent city and its invisible garrison. In the approach channels the Transport and Tractor Groups were moving in, bearing the forces for the main assault. But until the moon brought back the tides no further advance was possible.

Yet though ground action had been halted by the intertidal lull, the supporting arms were still at work. In the outer harbor the hastily summoned minesweepers were busy checking the anchorage areas. Over the harbor, from dawn to dusk, circled two tactical air observers from the escort carriers, keeping the commanders informed. Throughout the day, at 90-minute intervals, eight Marine Corsairs reported in to process the Inchon defenses with napalm and 500-pound bombs. From the fast carriers there arrived, again at 90-minute intervals, 12-plane deep support strikes which, after delivering their armament, relieved their predecessors as barrier patrol. To this effort, in the two hours preceding the landing, Task Force 77 would add three formidably armed strikes, each composed of eight ADs. In one flight the aircraft would carry three 500-pound bombs, in the second three 1,000-pound bombs, in the third two 500-pounders plus a napalm tank, and all had maximum loads of high velocity aircraft rockets.

Fire support was also an all-day proposition. The interval between the morning and afternoon landings had been divided into two periods, the first extending to H minus 25 and the second to H minus 5, for which roughly equivalent ammunition allowances were provided. Target assignments were similar to those of the morning, but with the weight of fire shifted inland: Toledo’s main battery was responsible for northern Inchon, Rochester had the area north of the tidal basin and Blue Beach, Kenya and Jamaica were given the region to the south and east of the zones assigned their sisters. From the enfilading peninsula north of Red Beach through the tidal basin, the salt pan, and on beyond Blue Beach, the water front was assigned to the destroyers and to the cruisers’ secondary batteries.

Not least of the problems stemming from the decision to land at Inchon was the difficulty of avoiding non-military damage to the city and injury to the population. Destruction of necessity there was, but Admiral Struble had enjoined the utmost accuracy and had warned against unnecessary devastation. All air strikes were controlled; within the areas assigned the fire support ships, the known military targets had been conspicuously marked, and only these were to be fired on without air spot and positive identification.

Slowly the waters rose again. By 1300 the transports and the LSTs were standing in, and as afternoon wore on they began to boat their troops. At sea Task Force 77 had been reinforced by Boxer, that veteran oceanic commuter, who after delivering her load of Air Force F-5Is had returned to the west coast, embarked an air group which had been flown across country from the Atlantic Fleet, and again recrossed the Pacific. Having fought her way through Kezia, Boxer now arrived, accompanied by Manchester and two destroyers, in time to launch for the beach preparation strikes. But three fast ocean crossings had taken their toll, the long-promised yard period had been indefinitely postponed, and that very morning a reduction gear failure had limited the carrier to steaming on three shafts.

At 1615 the strike groups from the fast carriers reported in and began the beach preparation work. By 1700, as the bombardment was about to begin again in earnest, more than 500 landing craft were churning the waters of Inchon harbor. Rain squalls drifting across the water mingled with smoke from fires in the city to diminish visibility as the armored LVTs with RCT 1 started in for Blue Beach, the faster LCVPs with RCT 5 headed north past Wolmi Do to the Red Beach boat lanes, and the DUKWs with two artillery battalions moved toward Wolmi Do. Then at H minus 25 the three rocket ships once more came into action. LSMR 403, with a load of 2,000 rockets, fired on Red Beach and the flanking area to the left while the others, with similar allowances, bombarded the tidal basin, Blue Beach, and the right flank area. Here the LVTs were set northward by the flooding tide, and LSMR 401 was forced to fire over some of the boat waves, an operation both impressive and discomforting tothe embarked Marines. At 1725, as scheduled, the bombardment ceased, the strafing planes came down, and the boats went in.

At Red Beach the two battalions of the 5th Marines got ashore on schedule to be opposed by scattered rifle, automatic weapon and mortar fire. Enemy resistance delayed clearing the beach area for a time, but in little more than an hour it had been overcome, the Marines were working their way in through the town to the dominating high ground, and tanks and troops from Wolmi Do were crossing the causeway to join in. At Blue Beach vigorous mortar fire had greeted the approaching LVTs, and before being silenced by Gurke and the rocket ships had destroyed one LVT by a direct hit. Congestion caused by the difficult entries to the landing areas converted the first wave into a column, while diminished visibility from smoke, rain, and approaching sunset caused some confusion in the follow-up waves and some dispersion along the shoreline. But here too the landing force advanced inland without serious difficulty.

As the Marines disappeared from the beaches into the darkening city they were not forgotten by the supporting arms. Air spot remained available for an hour or more, and call fire in direct support of the landing force was provided by the gunnery ships. For post-landing gunfire support Toledo’s batteries were at the disposal of division headquarters, the 5th Marines controlled Rochester and the 1st Marines Jamaica, while each battalion was assigned a destroyer with which it was in direct communication. Night illumination fire, which had proven extremely valuable during the Pacific War, was limited on D-Day by the configuration of the harbor: the destroyers were too close in for satisfactory employment of star shell and the cruisers too far out. But on subsequent nights this situation did not obtain, and illuminating missions were most successful.

Within the city fighting continued through the hours of darkness, but by midnight the landing force had reached its initial phase lines. The 5th Marines controlled the hills commanding Red Beach, and thus the source of their logistic build-up, and had advanced southward as far as the tidal basin; the 1st Marines had reached the designated high ground north of Blue Beach and commanding the main road to Seoul. The price of D-Day was 174 casualties, including 20 killed in action,1 missing, and 1 dead of wounds.

As had been expected, Inchon was not strongly garrisoned. Enemy strength within the city amounted only to some two thousand men of the 226th Marine Regiment, a comparatively new and ineffective unit. Weak to begin with, the forces defending the objective area had been further weakened by their southward displacement in response to Operation Lee and the ROKN landing on Yonghung Do. This move culminated, on the day of the Inchon landings, in a classic blow in the air, as a North Korean force was landed on that island and the outnumbered ROK garrison was taken off by PC 701. Next day the Communists woke up to what was going on to the northward, and departed hastily for the mainland.

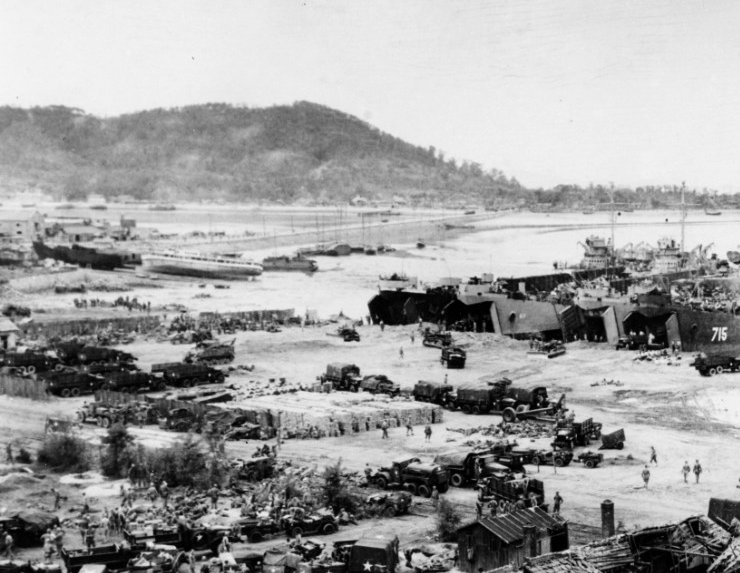

With the Inchon assault successfully accomplished the problem of the Attack Force was to maintain momentum for the advance inland, and this was inevitably a matter of logistics. Armies still march upon their stomachs; problems of supply, though often hidden by the smoke of battle, are always governing; at Inchon their impact was more than usually immediate. To support the landing force during the intertidal darkness LSTs had to be brought in; to bring in LSTs the landings had to be made at the height of the spring tides; to protect these ships Red Beach had to be cleared with all possible speed. An estimated six LST loads of ammunition, water, rations, vehicles, and fuel were needed; eight had been provided in the hope that six would survive. Recently recommissioned, outfitted with pick-up crews, in poor material condition and prone to breakdown, all eight had nevertheless reached Inchon, and beginning at H plus 60 went in at five-minute intervals. On Red Beach rifle and machine gun fire still continued, and the LSTs came in shooting, not always accurately; one had a minor collision with an ROK PC during the run in, and some were hit and holed by enemy fire. But all eight made it, and four more were put up on Green Beach on Wolmi after the DUKWs had landed the artillery and withdrawn.

Historically, some of the most vexing problems of amphibious warfare had been those concerned with the organization and administration of beachhead areas, and with the handling of assault supplies. In the course of the Second World War the employment for these purposes of details of combat troops, and of sailors from the amphibious shipping, had early proved unsatisfactory. The result had been the organization of commissioned Naval Beach Groups, and of Marine Shore Party Battalions, which while exacting the costs of specialization in terms of administrative overhead and shipping space had by now developed a considerable expertise. At 1840, H plus 70, Commander Naval Beach Group 1, Captain Watson T. Singer, landed in LST 883 and set up his command post on Red Beach. All through the night his men and the Marines of the 1st SPB labored to empty the LSTs so they could retract with the morning tide and make room for others to be brought in. At the same time another all-night exercise was taking place on Wolmi Do, where the Beach Group’s construction battalion was installing a pontoon dock, and where the supplies from the Green Beach LSTs were being unloaded for further delivery by way of the causeway. No effort was made to put important amounts of cargo in through Blue Beach owing to its inferior hydrography and intractable approaches; there material for immediate consumption only was sent in by small craft, and the beach was closed at 2100 on D plus 1.

Despite all geographic and hydrographic complications, the logistics of the assault phase turned out well. The early morning tide of the 16th saw all first echelon LSTs retracted and nine more run up on Red Beach; on the evening tide seven more were withdrawn and six put in; by 2100 almost 15,000 personnel, 1,500 vehicles, and 1,200 short tons of cargo had been put ashore. On D plus 2 Rear Admiral Lyman A. Thackrey, Commander Amphibious Group 3, who had just arrived from San Diego in the AGC Eldorado, was put in charge of port operations, and moved ashore with members of his staff. There his presence proved helpful in coordinating the efforts of the undermanned Beach Group in its three non-contiguous unloading zones, in setting up an unloading schedule, and in getting the inner harbor into operation. Here speed was essential, for with the end of the spring tides on D plus 3 the beaches would become inaccessible to LSTs, and here speed was obtained. On the 16th heavy cranes were landed on Wolmi Do, and moved across the causeway to the tidal basin, where unloading began on D plus 2, far sooner than had been anticipated.

All first echelon shipping had been emptied by D plus 4. Three days later 53,882 persons and 6,629 vehicles were ashore, and the 25,512 tons of cargo unloaded more than doubled the X Corps target figure for that date. Figures like these doubtless make arid reading; it takes an act of the imagination to translate tonnage into ammunition, water, rations, and plasma; but figures like these also make for victories. By the time the Army’s 2nd Engineer Special Brigade assumed control of the Inchon port area the limitations on the supply of the front, far from being hydrographic, were a function of the availability of motor transport.

There were, of course, logistic problems afloat as well as ashore. The movement of the Attack Force to Inchon and the extended and extensive activities of the other units of Joint Task Force 7 placed new loads upon the Service Force organization. In the weeks prior to the invasion the resupply of combatant ships had been increasingly concentrated at Sasebo, which by now had taken on the characteristics of a major fleet base. But with the transfer of so large a portion of theater naval strength to the west coast of Korea, the job of backing up at Sasebo was turned over to Captain Wright’s Service Division 31, and Servron 3, which had moved up from Okinawa in early September, was deployed forward to the objective area.

Four task groups had been created for the logistic support of "Chromite." To meet the needs of Task Force 77 a Mobile Logistic Service Group with two oilers, a reefer, and Mount Katmai, still the only ammunition ship in the Far East, was on station in the Yellow Sea. For towing and salvage work the tug Mataco and the salvage vessel Bolster were ordered up to Inchon, along with the oiler and five cargo ships of the Objective Area Logistic Group with fuel, ammunition, food, and stores. For follow-up resupply and maintenance ComServron 3 brought forward the Logistic Support Group: one oiler, one gasoline tanker, two destroyer tenders, two repair ships, two more cargo types, and a reefer. In-port nourishment of the Attack Force was complicated by the crowding of the anchorage, the tides and currents which made alongside loading of ammunition risky, and the shortage of lighters which made transfer by boat a time-consuming affair. Hard work was required of both the givers and the receivers, but everything necessary was accomplished and nobody went short.

From D plus 1 the campaign for Seoul moved rapidly forward. By the end of this day the Force Beachhead Line, some seven miles inland from the landing points, had been secured. In Inchon the Korean Marines were mopping up the last defenders. On the main road to Seoul five oncoming enemy tanks had been destroyed, two by Corsairs from Sicily, three by the 1st Marines. The transfer of control from ship to shore was underway: an observation plane strip was in operation, shore tactical air control parties had begun to take over some of the business previously handled by the Tactical Air Direction Center in Mount McKinley, and at 1800 the division command post displaced forward from Wolmi to Inchon and General Smith assumed control of operations ashore. Marine casualties for the first two days totalled 222, of whom 22 were killed in action, 2 were reported missing, and 2 had died of wounds; as against these figures, far below those anticipated by the medical planners, some 300 prisoners had been taken and an estimated 1,350 additional casualties inflicted on the enemy.

Although the North Koreans were by now reacting vigorously, D plus 2 was also a day of rapid progress. After repelling heavy early morning counterattacks the 1st Marines, supported by Corsairs from Sicily, pushed eastward along the Seoul highway toward the village of Sosa. Four tanks were destroyed during the advance, but resistance continued strong, and at 1415 the tactical air people put out an emergency call for all possible support. Badoeng Strait was fuelling destroyers, but with Sicily’s aircraft already committed, she turned to, cast off her customers, and had all planes airborne by 1558. By evening the 1st Marines were within 1,500 yards of Sosa, while the 5th Marines had gained a great strategic prize. Turning left off the main highway behind the 1st Marines, RCT 5 had barrelled up the road toward Kimpo airfield, with support from the air and from cruiser gunfire, and by nightfall had occupied the high ground east of the field and had pushed troops out onto the landing area itself.

Behind the front, reinforcements were beginning to arrive and transfer of control ashore continued. At Inchon the 32nd Infantry, first of the 7th Division’s units to reach the objective area, arrived on D plus 2 and at once began its administrative landing. At 1800 that evening the shore-based TADC assumed control of all close air support, and next day the division Fire Support Control Center took over responsibility for the integration and control of air support, artillery, and naval gunfire.

For the next three days the 1st Marines pressed eastward against stubborn opposition. At Sosa, on the 18th, there was more heavy fighting, but the objective, a commanding hill northeast of the town, was gained with the help of the escort carriers’ aircraft and of the cruisers’ guns. Here was the half-way mark between Inchon and Yongdungpo, the industrial suburb of Seoul which lies on the south bank of the Han, and here enemy organization began to improve and enemy artillery was first encountered. Nevertheless the advance continued: by morning of the 20th the regiment controlled the high ground overlooking Yongdungpo and the Seoul-Suwon corridor, and had swung left to reach the banks of the Han, while the 32nd Infantry was moving up along the right flank.

For some reason the enemy had chosen to defend Yongdungpo in force. Air strikes from Badoeng Strait and artillery fire were called down upon the town, but when the attack was launched on the 21st the Marines met heavy resistance. Forward elements, finding themselves overextended, were forced to disengage under cover of strafing and bombing by Sicily’s Corsairs, some of which was directed within 30 yards of the front lines. But Communist counterattacks were beaten off, and the end of the first week of fighting found the 1st Marines 16 miles inland from their landing point, with one company deep in Yongdungpo making trouble for the city’s defenders, and with the rest of the regiment preparing for the final assault into the town.