The Navy Department Library

Chapter 5: Into the Perimeter

History of US Naval Operations: Korea

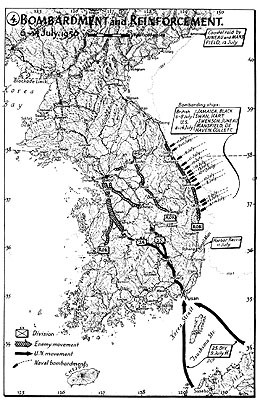

Part 1. The Korean Theater Part 2. 5-17 July: East Coast Bomdardment

Part 3. 3-30 July: The Pohang Landing

Part 4. 10-30 July: Seventh Fleet Operations

Part 5. 7 July-2 August: Patrol Planes and Gunnery Ships

Part 6. 23 July-6 August: The Marines Arrive

Part 1. The Korean Theater

Although the conduct of war is always, in large measure, an exercise in applied geography, in Korea this was more than usually the case. On land, at sea, and in the air, the movements of forces and the employment of weapons were greatly affected by the nature of the arena.

The Korean peninsula, divided by the fortunes of international politics, itself divides the Yellow Sea from the Sea of Japan. S-shaped, and with its long axis oriented generally north and south, the country lies between the parallels of 34° and 42° North, and spans the latitude between Los Angeles and central Oregon, or between North Carolina and the southern New Hampshire border. Although Korean territory extends for almost 600 miles from north to south, the distance between eastern and western coasts nowhere exceeds 200 miles, and in places is little more than half that distance. One consequence of this geographical configuration is of striking military importance: with a total area of some 83,000 square miles, or of 85,000 if all the islands are included, only a small strip along the northern border is more than 100 miles from the sea.

But although Korea is surrounded by sea, its situation to leeward of the greatest of continents has given it a climate of extremes. While summer in the north is temperate the mountain winter is extremely bitter: even on the seacoast the mean January temperature at the Russian border is but 15 Fahrenheit. In southern Korea, by contrast, the climate is warm enough to permit the growing of cotton; summer temperatures reach the nineties, and the rains of June and July produce an exhausting combination of heat and humidity; at the peninsula's southwestern tip winters are frost-free and the August mean is 80°. Summer is also the season of typhoons, which form in the Marianas and move northwestward toward the East China Sea. Typically, they recurve in time to pass over southern Japan or through the Straits of Tsushima, with only their fringes affecting southeastern Korea; sometimes, however, they recurve late and cross the peninsula; always their approach brings problems for the navigator and the strategist.

For five years prior to the outbreak of war the 38th parallel had divided Korea into roughly equal parts. But the division was an illogical one, resulting in such oddities as the isolation of the Ongjin peninsula in the west, and the separation of the city of Haeju from its port facilities; still more important was its separation of the populous and agricultural south from the complementary industrial economy of the north. Yet the parallel was not the country’s sole internal barrier, for long before geographers drew lines on maps, nature had divided this peninsula and subdivided it again.

Much of Korea is mountainous. In all the peninsula there are no true flatlands or plains. Like Italy with its Alps, Korea is protected from the continental land mass to the north by high mountains which fill the triangular area above the mouth of the Yalu River, and extend beyond the border to the Manchurian plain. Much of this triangle lies above 3,000 feet; peaks of over 6,000 feet are not uncommon; only along the coast does the altitude drop below 1,500 feet. The Yalu and Tumen Rivers, which separate Korea from Manchuria and from the Russian Maritime Provinces, have their origins in the Pai Shan range, which towers above 9,000 feet and is capped by perpetual snow.

Only three significant routes of access to the peninsula penetrate this formidable terrain. Of these the most important is the western corridor, along the lower reaches of the Yalu, through which the Japanese advanced in 1905 against the Russians and through which Communist Chinese forces would move against the United Nations. But there is also a gap in the mountains in central North Korea, formed by the valleys of the Tongno and Chongchon Rivers, while in the extreme northeastern corner of the country narrow valleys and a coastal strip lead down from eastern Manchuria and the Vladivostok region.

From the northern mountain mass a rocky cordillera runs southward, paralleling the eastern coast; along this shore, except in the embrasure at the head of the Korean Gulf between the seaport cities of Wonsan and Hungnam, the mountains descend steeply to the sea. North of Wonsan the coast is somewhat indented, with a number of harbors and towns; to the southward it is almost unbroken and the Korean divide, running within ten miles of the Sea of Japan, hems in a narrow and isolated ribbon of land where population is sparse, towns are small, and ports are few. Behind the coastal range the mountain spine recurves to.the southwest, diminishes for a time in altitude, and then rises again in the south central region to form an isolated massif with peaks of five and six thousand feet. From the axial range, throughout the length of the peninsula, razorbacked spurs run off to west and southwest, compartmenting the country.

These mountain spurs and isolated masses divide the populous western part of Korea into a series of river basins, draining into the Yellow Sea and the Korean Strait, which in earlier times formed the principal geographic and economic units of the country. Although not navigable by ocean-going ships, these rivers remain of considerable internal importance: the principal Korean ports lie at their mouths, and the capitals of North and South Korea only a short way upstream. Five of these rivers, two north and three south of the 38th parallel, deserve the attention of the student of the Korean War.

The Chongchon River, northernmost of the strategically important west coast streams, is blocked to ocean shipping by drying mud banks which extend far offshore. But the central rail and road route to the north runs down its valley; the town of Sinanju, near the river’s mouth, is important as the junction of the western and central routes from Manchuria; and the bridges across the river are vulnerable to air attack.

Sixty miles to the southward the Taedong River, scene of the massacre of the crew of the General Sherman, empties into the Yellow Sea. Near its mouth lies Chinnampo, a city of some 90,000, seaport of the important northern mining and industrial region. Fifteen miles upstream the city of Kyomipo contains Korea’s largest iron and steel works; 30 miles to the northeastward lies the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. Once the ancient capital of the country, Pyongyang contains the tombs of long-dead monarchs, including that of Kija, legendary inventor of the topknot. In the Sino-Japanese War it was the scene of considerable fighting; early in the century it became the last abode of the deposed emperor. Under the Japanese it developed into a considerable manufacturing city, with industry based on the neighboring coal mines, and in due course, as the largest city in the north, became the capital of the People’s Republic. Like the bridges over the Chongchon at Sinanju, those which cross the Taedong at Pyongyang are of strategic significance.

Most important of Korea’s rivers is the Han, whose basin extends 150 miles from north to south and half that distance from east to west. With its principal tributaries, the Imjin and the Pukhan, the Han drains a major portion of the country on both sides of the 38th parallel. Rising only a few miles from the east coast, these streams wind through the central mountains before joining to pass the capital of Seoul and empty into the Yellow Sea near the principal west coast port of Inchon. For some 60 miles above its estuary the lower Han runs in a more or less east-west line, cutting the western lowlands and forming a potentially important and defensible military position.

South of the Han basin and west of the coastal range the country is drained by two important rivers. Some 90 miles below Inchon the Kum descends from the central massif to empty into the Yellow Sea; at its mouth lies Kunsan, a principal shipping center for the agricultural regions of southwestern Korea. In the southeastern corner of the peninsula, between the coastal range and the central highlands, the Naktong River flows southward for 100 miles or so, then east, then south again to empty into the Korean Strait. Near the mouth of the Naktong is the excellent harbor of Pusan, second city of the country and port of ingress from Japan. To the north the Naktong basin is divided from that of the Han by mountains more than 3,000 feet high; on the west it is separated from the Kum by the southern massif. Between these mountain masses the divide between the Naktong basin and those of the Han and Kum diminishes in altitude; through this gap runs the main line of Korean communications, linking Japan and Pusan with the areas of heaviest population and agricultural production and with the capital at Seoul.

The geography of Korea, in sum, is dominated by three main features: a north blocked by high mountains; an east coast strip isolated by the mountain spine; and a broken piedmont to the west and south divided into a series of river basins. Upon this pattern industrial man, in the person of the Japanese, imposed his own geography. But although railroads, like faith, can sometimes move mountains, in Korea this movement was only a partial one. A traffic pattern could be developed which would unite the river basins, but the linking of eastern and western provinces remained incomplete. The mountain framework, broken, jumbled, and forbidding, continued to dominate the life of the country and to impose a north-south orientation which made division at the 38th parallel the more painful.

The first Korean railroad, built early in the century by the Japanese, linked the port of Pusan with the capital at Seoul. Although its construction required 99 bridges and 22 tunnels, it was completed by the time of the Russo-Japanese War. During that war its northward extension, from Seoul to Sinuiju on the Yalu River, was rushed to completion for strategic purposes. But a decade elapsed before the coasts were linked by a line through the mountain gaps between Seoul and Wonsan, and still longer until the construction of the east coast railroad, leading south from Siberia, began the transformation of fishing villages into industrial towns.

By 1950 the main structure of rail and road communications had assumed an X-shaped pattern, with the crossing at Seoul. From Manchuria in the northwest a line of double track spanned the Yalu at Sinuiju and ran southeast to Sinanju. There it was joined by a line which crossed the border below the Suiho reservoir, and by one coming from the upper reaches of the Yalu by way of the Tongno-Chongchon gap. From Sinanju, where these lines merged, the double track ran south to Pyongyang, Seoul, and beyond. On the far side of the mountain masses, widely separated from this west coast network, another rail line came south from the Vladivostok complex. One coastal spur extended from the lower Tumen River to Najin near the Russian border; farther inland, the main line ran south to Chongjin, along the shore to the new manufacturing cities of Hungnam and Wonsan, and on through the mountains to Seoul. On the east coast south of Wonsan the track extended as far as Yangyang, just above the 38th parallel, but from Yangyang to Pohang, 65 miles above Pusan, movement depended on road and sea.

The routes from the north thus converged at the Korean capital. Below this hub the railroad lines spread out again through South Korea. Two ran southeastward to the Pusan area, one leading directly from the valley of the Han into that of the Naktong, while the main line, now doubletracked, passed westward through Taejon in the Kum basin. From the latter, branches extended to the southwestern ports of Kunsan, Mokpo, and Yosu, but there was no south coast line, and rail traffic between Pusan and the southwestern ports had to be detoured northward around the central mountain massif.

To this extent the mountains remained unconquered. The lack of lateral communication remained the dominant feature of the transportation nets, road and rail alike. Of intercoastal rail links there were but two, one running north and south between Seoul and Wonsan, and one east and west, connecting the Wonsan-Hungnam region to Sinanju and Pyongyang. The Korean transport system thus rested upon three focal points, the Wonsan area on the east coast, the Pyongyang-Sinanju complex on the west, and Seoul. This situation sufficiently explains the strategic importance of these regions, for while the Korean road net was much more extensive than that of the railroad, and permitted access to most of the mountain regions, the roads were generally poor, unimproved, and unsuited to heavy mechanized equipment, and the anatomy of the highway system followed that of the rail lines.

Inevitably the scheme of maneuver adopted by the North Korean army for the conquest of this corrugated country was governed by the orientation of transport routes. The war had begun with a four-pronged invasion. The principal attack, delivered by the North Korean 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions and the 105th Armored Brigade, and with two more divisions in reserve, was aimed south toward Seoul along the valley line from Wonsan. To the west the North Korean 6th Division overran the isolated Ongjin peninsula, and then joined with the 1st Division to move southeast, along the main line from Pyongyang, through Kaesong to the capital. In the central mountains the 2nd and the newly organized 7th Divisions attacked southward to Chunchon, terminus of a branch rail line from Seoul, after which the 2nd Division moved southwesterly down the railroad toward the capital while the 7th marched southward over mountain roads toward Wonju and the eastern of the two rail lines to Pusan. On the east coast beyond the divide, in a theater all its own, the North Korean 5th Division advanced southward along the shore road, leapfrogging ahead with small-scale amphibious operations.

Four prongs became three as the mass of the invading troops converged upon the capital’s transportation nexus. In this second phase the 5th Division continued its independent operations east of the mountain spine, while in the central mountains the 7th Division, supported by constabulary troops, threaded its way southward through Wonju in the direction of Andong. But the overwhelming bulk of the North Korean army, five first-line infantry divisions, two divisions of recent conscripts, and the armored brigadle, had to be funneled through the Seoul complex. Once through the capital three divisions were peeled off to the southeast, and sent by rail and road to Wonju and Chungju to join the troops coming south through the mountains, while the remaining five moved down the main road. It was the advance guard of this massive force that Task Force Smith had run up against on 5 July.

By the end of the second week of war the American 24th Division had been driven out of Chonan and was retiring on Taejon. Somewhat surprisingly, despite its overwhelming numerical strength, the North Korean army now slowed its advance: a full week was to pass before the battle of Taejon began. Although not apparently appreciated at the time, this was the first evidence of the logistic limitations which forced the enemy to conduct his offensives in a series of massive lunges, and which prevented the maintenance of continuous pressure during an advance. Only on 20 July, after a bitter three day fight in which General Dean, the division commander, was captured, was Taejon lost and the 24th Division forced once again to retreat.

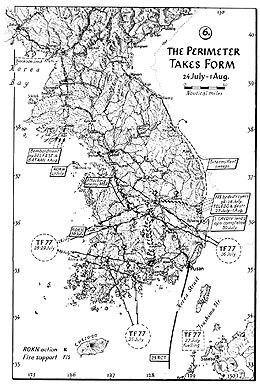

By this time the invasion was again a four-pronged affair. Unknown to the Americans, the North Korean army had split its main force a second time, and had sent the 6th Division with attached troops southward to Kunsan, which it entered on the 16th, and toward the southwestern tip of the peninsula. In pursuit of the retiring 24th Division the enemy main body, now seven divisions strong, pressed southeastward from Taejon along the main road and rail line toward the saddle which gives access to the Naktong Basin. Five dlivisions were moving through the mountains to the Andong area, while on the east coast the 5th Division continued its solitary southward course.

Although this east coast threat was opposed only by the ROK 3rd Division, it was accessible to bombardment from the sea. ROK forces were also operating on the northern mountain front in the Andong-Chungju area, and the U.S. 25th Division was moving up from Pusan to Hamehang, north of Taegu, to block this enemy advance. It was the plan of General Walker, who assumed command of all ground forces in Korea on 13 July, to employ the 1st Cavalry Division to reinforce the 24th I)ivision on the main enemy route of advance, and to push the 29th Infantry, which was coming from Okinawa, west from Pusan to a blocking position south of the central hill mass. But by mid-July North Korean forces had covered more than half the distance to Pusan, and had occupied the line Chonju-Taejon-Yongjin-Yongdok, while the 1st Cavalry and the 29th Infantry had not yet arrived.

As Korean physiography and the Korean transportation net governed the land scheme of maneuver, so the hydrography of the area profoundly affected naval capabilities. The Korean coastline, generally straight along the Sea of Japan but deeply convoluted on south and west, has a length of some 5,400 miles. The steepness of the east coast, where the mountains rising from the sea confine road and railroad to a narrow coastal strip, has its underwater counterpart: except in the Gulf of Korea, off Wonsan and Hungnam, the 100-fathom curve runs close to shore, coastal shipping is exposed, and warships can get within gun range of land communication facilities. But in the south and west conditions are very different, and the countless islands and deeply indented bays which mark the disappearance of the mountain ranges into the sea provide shelter for coastal traffic. The operations of major fighting ships are restricted, and effective supervision of coastal shipping calls for small craft of shallow draft. On the western shore further complications arise from the extraordinary hydrographic conditions of the Yellow Sea: whereas the tidal range in the Sea of Japan is of the order of a foot or two, here it ranges from 20 to 36 feet; currents are considerable and the water turbid; nowhere are there depths greater than 60 fathoms, and the 20-fathom line runs ten miles offshore. Extending far from land and exposed at low tide, the mud banks which trapped the French frigates a century ago remain a hazard for the unwary.

These hydrographic facts of life and the very limited forces available combined to dictate the early activities of the Navy. Task Force 77 had been withdrawn to Okinawa, and the period from 5 to 17 July saw naval effort concentrated on the movement of troops and supplies into Pusan, gunfire support of ROK forces resisting the enemy east coast advance, and the planning of future operations.

Part 2. 5–17 July: East Coast Bombardment

Off Korea’s eastern shore, on 5 July, Jamaica relieved Juneau of her bombardment duties, and Admiral Higgins’ flagship headed for Sasebo to replenish. On the same day the British cruiser, accompanied by Black Swan, fired on the road and bridge in 370°16' N, where the coastal route runs close to the sea, and on the 6th shot up oil tanks, bridges, and shipping, and silenced a shore battery at Chumunjin. On the 7th, as Black Swan was relieved by Hart, the British cruiser destroyed an oil tank north of Ulchin, cruised northward firing at the cliff roads, and ended the day with an effective bombardment of Yangyang, the end of the coastal rail line from the north, where more oil tanks were destroyed.

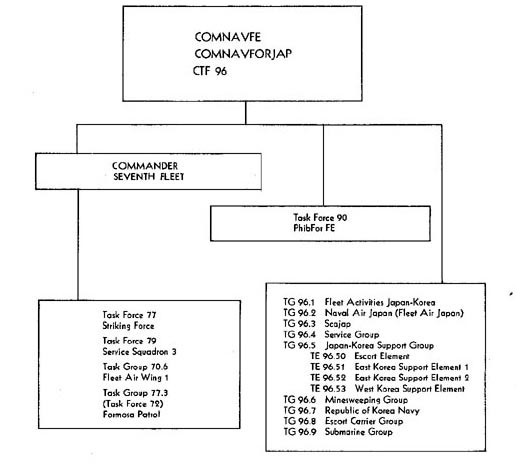

While Jamaica was at work, the reinforcement and reorganization of the South Korea Support Group was underway in accordance with ComNavFE’s Operation Order 8-50. These instructions had been promulgated while the carriers were striking Pyongyang, and as Task Force 77 retired southward Admiral Andrewes was detached to join the Support Group; with Belfast, Cossack, and Consort, he proceeded to Sasebo where Juneau was replenishing. On 6 July Higgins and Andrewes flew to Tokyo to consult with Admiral Joy on the reorganization of the force and on problems of coordination with the Army in Korea and with the ROK Navy. An additional matter of importance, which had formed the subject of a dispatch from ComNavFE the previous day, was the question of the rail line on the northeast coast of Korea between Chongjin and Wonsan. Interruption of this line, both vital and vulnerable, would force the enemy to move rail traffic from the Vladivostok region by a circuitous route through Manchuria and down the west coast. Such interruption was urgently desired by Admiral Joy.

On the east coast 8 July saw Jamaica and Hart, now joined by Swenson, operating in the neighborhood of 37°. There, where the highway skirts the water’s edge, road traffic was taken under fire, enemy shore batteries were engaged, and the British cruiser received a hit from a 75-millimeter shell which killed four and injured eight. Late in the day an alarm from Pohang brought Jamaica, Hart, and Swenson south at speed, while Mansfield broke off her escort duties and Juneau got underway from Sasebo. All five ships joined off Pohang on the morning of the 9th, but although the situation ashore was serious it was not yet out of control.

Since the threatened encirclement of the Korean forces north of the town remained only a threat, Jamaica was relieved and ordered to Sasebo, the destroyers were left to provide fire support, and Juneau proceeded to Pusan. There Admiral Higgins spent the day in conference with Korean and U.S. Army authorities, and in attempts to round up more interpreters and to obtain some solid information on the situation ashore. With evening the cruiser proceeded north again, and from 0200 to 0330 of the 10th bombarded the port of Samchok, following which she headed south to check once more on the situation at Pohang. But another more northerly mission was now brewing.

On the 10th a dispatch from ComNavFE instructed Higgins to extend his blockade as far north as practicable, and reemphasized the importance of the coastal tunnels on the Chongjin-Wonsan railroad. With these targets in mind equipment had already been procured and plans worked out to land a demolition party, and following another night on coastal patrol and a dawn bombardment of Yangyang and Sokcho, Juneau and Mansfield headed north for the region between Tanchon and Songjin.

At 2000 on the 11th the ships slowed and the demolition party, a lieutenant and four enlisted Marines and four gunner’s mates, led by Commander William B. Porter, Juneau’s executive officer, transferred from the cruiser to Mansfield. Moving onward through the darkness the two ships reached the target area, ten miles south of Songjin, at midnight. Mansfield closed to within 1,000 yards of the beach, hove to and lowered her whaleboat, and the demolition party went on in. The landing was without incident, no opposition was encountered, and after considerable scrambling around the precipitous terrain the party managed to locate the tunnel and rig two 60-pound charges for detonation by the next train.

Although the results of the enterprise were unobserved, later reports of broadcasts by the North Korean radio seemed to indicate that the scheme had worked. By 0330 Commander Porter's party was back aboard, safe and sound, and with the distinction of having been the first members of the armed forces of the United States to invade Korea north of the 38th parallel. With their mission completed Juneau and Mansfield headed south again, and by noon of 12 July had rejoined Swenson on patrol between 37° and 38°.

The North Korean 5th Division had by this time reached south of the 37th parallel, and on the 12th the Army called for naval bombardment of the cliff road in 36°50'. On the 13th De Haven came up from Pusan with an artillery major for Admiral Higgins' staff and, although air and ground observers were still unavailable, communications were established with the 25th Division artillery detachment which was supporting the eastern front. Coastal fog on the 13th made targets hard to distinguish, but Juneau and De Haven nevertheless spent a busy day shooting at the cliff road in response to the Army request, at troops in Ulchin, at Mukho, at a railroad yard on the local line which leads back into the mountains, and at POL storage in the harbor of Samehok. The shooting was good, but the distressing ineffectiveness of 5-inch shells against roads and bridges made the arrival of 8-inch gunned cruisers from the United States appear increasingly urgent.

No requests from ashore were received on the 14th, and visibility remained poor, but with evening Juneau let off a few rounds against truck headlights on the road south of Ulchin. On the 15th, however, the cruiser and De Haven had a big day on the 20-mile stretch between 36°34' and 36°52' where the road runs generally close to the sea. For the first time an Army liaison plane was available to provide air spot, and a total of 645 rounds of 5-inch ammunition, expended against troops, shore batteries, and other targets, included a little night work against road traffic with the aid of star shell illumination. Joined hy Mansfield on the next day, Higgins covered the coast between 36°30' and 37°15', and the three ships fired 173 rounds against targets of opportunity along the highway.

The 17th found Juneau fueling at Pusan while Admiral Higgins conferred with representatives of the Korean Navy. In the absence of the flagship, Mansfield and De Haven fired more than 400 rounds at miscellaneous targets in the same coastal area, and the British returned to the business of coastal bombardment with the cruiser Belfast and the destroyer Cossack. All this was useful, but the next day brought wholly unprecedented activity along the east coast in the form of an amphibious landing and a strike by the Seventh Fleet carrier force.

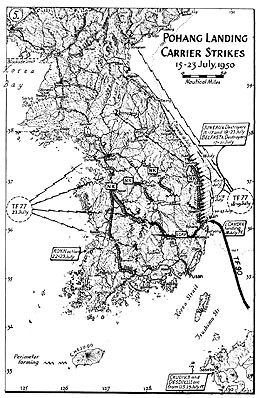

Part 3. 3–30 July: The Pohang Landing

In the course of the first week of July American infantrymen had made contact with the enemy, the 24th Division had completed its movement to Korea, and the 25th Division had begun its embarkation. The Air Force had carried out attacks against the invading army and against targets of opportunity. A carrier strike had been flown against the North Korean capital, and the gunnery ships of Naval Forces Japan, augmented by British units, had continued their bombardment of the enemy’s east coast invasion route. This week saw also the commencement of planning for the first amphibious operation of the campaign.

Admiral Doyle had brought his ships into Sasebo on 3 July only to find that his prospective passengers had already departed. Next day, on orders from Admiral Joy, he flew back to Tokyo with members of his staff to work on a plan for the landing of two regimental combat teams of the 1st Cavalry Division on the west coast of Korea. For this operation CincFE’s preferred objective was Inchon, seizure of which would give access to the Seoul transportation complex and would cut the enemy’s main supply route; alternatively, it was proposed to land the cavalrymen at Kunsan, at the mouth of the river Kum, whence they could strike inland toward Taejon and the enemy’s right flank. The concept of a landing at Inchon was certainly strategically appealing, and was the germ of the operation which in September would put the enemy to ignominious flight. Its proposal in early July was evidence of early confidence in the efficacy of American intervention. But a few short days sufficiently demonstrated the visionary aspects of the idea, and even Kunsan, a much more modest alternative, was soon seen to be an impossibility. Almost at once the problem came to be not one of throwing the 1st Cavalry Division against the enemy’s flank, but of getting this force into Korea while there remained some Korean territory to get into.

For four days Doyle’s staff struggled with the Inchon and Kunsan problems. But although these objectives were discarded on the 8th, the work was not wholly wasted, for the need for an amphibious operation remained. Not only was it necessary to get the troops into Korea at the earliest possible moment, but to do so if possible without putting them through Pusan. By 6 July that port had handled 55 ships, more were on the way, and although the Army had set up a Pusan Logistical Command on the 4th, the port facilities were overloaded and in danger of being swamped.

Thus the situation called for a landing on the southern or eastern coast. The problem was to find an objective with easy access to the interior, north or west of Pusan and south and east of the advancing enemy. On 10 July Admiral Doyle’s suggestion of Pohang was accepted, planning proceeded at an accelerated rate, and the activity was legalized on the 12th when Commander Naval Forces Far East issued his Operation Order 9-50 . The affair was christened with the code name "Bluehearts."

The town of Pohang, which would shortly receive these visitors from overseas, had some 50,000 inhabitants. Located about 65 miles north of Pusan, it lies on the western shore of Yongil Man, a bay about six miles wide. To the southeast Yongil Man is protected by a high peninsula; on the west it is bordered by dunes, with sand hills beyond; the bottom affords good holding ground. At Pohang there were two long jetties with ten feet of water alongside where landing craft could unload; from Pohang rail and road communications ran south to Pusan and, more important for the purpose of the moment, west through the mountains to Taegu; there was an airstrip of sorts nearby. All in all, the choice of objective was both obvious and sound.

The speed with which the operation was planned and mounted was remarkable. Normal lead time for an amphibious operation is measured in weeks if not in months, but this objective was selected on 10 July, the expedition sailed on the 14th and 15th , and the landing was made on the morning of the 18th . Such an unprecedented schedule gave little time to collect information and to plan, train personnel, and assemble and modify gear. That these dates were met must be reckoned a considerable feat.

There were, it is true, certain favoring circumstances. The Amphibious Group was a good outfit, and knew its business; although the 1st Cavalry Division lacked amphibious experience its men were willing and put their backs into the work. As a consequence of CincFE's plan for amphibious training of occupation troops there were present in Japan, in addition to Doyle's ships, detachments from the Pacific Fleet Amphibious Training Command, including an Air and Naval Gunfire Liaison Company or "Anglico , " which could be assigned to the Cavalry Division's staff to help with the conduct of the operation. All concerned, Army and Navy alike, were cheek by jowl in Tokyo, so that written communications could be eliminated and the business got on with by high-speed conversation.

But there were also major problems. The first of these, and one which would recur throughout the war, was the problem of intelligence: nobody knew much about Pohang. If one proposes to put landing craft up on the beach in order to get troops ashore it is desirable to know the underwater characteristics of the objective area, but although American forces had occupied South Korea, and had undertaken to conduct a mapping program, Korean beach gradients and much else remained a mystery. This, it may be observed, was no new experience; the same situation had prevailed in the Philippines after 40 years of American occupation. In January 1945, when American attack forces set forth for Lingayen Gulf and the reconquest of Luzon, information concerning those beaches, which other Americans had previously defended against the Japanese, was conspicuous by its absence. Yet experience had not taught convincingly the need for basic intelligence studies, and so far as South Korea was concerned the lack of information, as Admiral Doyle remarked, "was appalling."

Fortunately there was a solution. Pohang was still in friendly hands. On 10 July U.S. troops were reported guarding the airstrip, an aviation engineer unit was landed by LST, and Fifth Air Force was preparing to move in a fighter squadron. On the 11th some officers from the Amphibious Group and Cavalry Division staffs were flown to Pohang, to return two days later with useful and previously unavailable information. On the 15th a second group flew across to make such preparations for the landing as were possible, and to keep the command informed of enemy progress down the coastal road.

There was also a problem of shipping. The Amphibious Group had been sent westward for training purposes, and the four vessels available - a command ship, an attack transport, an attack cargo ship, and an LST - were wholly inadequate to the contemplated task. Fifteen more LSTs were procured from Scajap, and two attack cargo ships, Oglethorpe and Titania, were borrowed from the Military Sea Transportation Service for the assault phase. For the follow-up echelons shipping was also provided by MSTS, in the amount of three transports, a dozen Scajap LSTS, and four Japanese time-charter vessels.

Although Oglethorpe and Titania had retained the classification of AKA while assigned to MSTS, their equipment and personnel had been radically reduced. The first problem was met by Fleet Activities Yokosuka, where landing craft, boat fittings, and much miscellaneous gear including slings, nets, and the like were installed. At the same time an emergency air movement of boat crews and other specialized personnel from the west coast helped to strengthen the crews, but the two ships were still below peacetime complement when the force set sail, and far below that of wartime.

The load imposed on Fleet Activities Yokosuka in preparation for "Bluehearts" was not limited to the modification of the AKAs. To assist in unloading at the objective half a dozen LSUs were reactivated; the proposal to tow these to Poliang by LST superimposed a requirement for the manufacture of towing gear. Both in this high-speed shipyard work and in the loading of the Attack Force there was reason to be grateful for Japanese facilities and Japanese labor. The larger ships, which carried an average of 138 vehicles and 575 tons of bulk cargo, were loaded in little over a day, and the vehicle-laden LSTs in only four hours. Despite all difficulties the sailing date was somehow met.

The employment of Scajap LSTs in both the assault phase and the follow-up echelons, and the use of chartered Japanese merchant ships, created an unusual situation. Seldom, indeed, do men embark for war in ships manned and navigated by enemy aliens. Since control of the Scajap fleet was exercised through the Civilian Merchant Marine Committee, an agency of the Japanese Government, its administration was somewhat unwieldy. Always, of course, there was the language problem. But the most important complications were of a military nature. If sailed independently, the only contact with these ships was through Japanese radio channels, cumbersome and presenting difficult questions of security. Even when sailing in company, problems arose in communicating with units which could not be issued classified publications. Placing of Navy radiomen and quartermasters aboard, while answering some difficulties gave rise to others, not least in the manifestation at meal time of cultural differences between east and west. Yet these problems, if not overcome, were mitigated by various expedients, and the Scajap LSTs gave yeoman service throughout the war.

Table 6. - POHANG ATTACK FORCE

| TASK FORCE 90. ATTACK FORCE. | REAR ADMIRAL J. H. DOYLE . |

Task Force 91 . Landing Force. |

Major General Hobart Gay, USA. |

Task Group 90.1 . Tactical Air Control Group. |

Commander Elmer Moore, USN. |

Task Group 90 .2 . Transport Group |

Captain Virginius R. Roane, USN 1 Amphibious Command Ship 1 Amphibious Transport 3 Amphilious Cargo Ships |

Task Group 90-3. Tractor Group. USS Cree (ATF-84) |

Captain Norman W. Sears, USN 1 Landing Ship Tank 15 Supreme Commander Allied Powers, Japan LST as assigned 2 Fleet Tugs 1 Salvage Ship |

Task Group 90-4 . Protective Group |

LCDR Darcy V. Shouldice, USN LCDR Darcy V. Shouldice, USN 1 Minesweeper 3 Coastal Minesweepers

|

Task Group 90-7 . Reconnaissance Group |

LCDR. James R. Wilson, USN 1 High Speed Transport |

Task Group 90.8 . Control Group. |

LCDR Clyde E. Allmon, USN 1 High Speed Transport 1 Fleet Tug |

Task Group 90.9. Beach Group. |

LCDR Jack L. Lowentrout, USN Underwater Demolition Team |

Task Group 90.0 . Follow-up Shipping Group. |

Captain Daniel J. Sweeney, USN 2 Transports 12 Supreme Commander Allied Powers, Japan Landing Ship Tanks |

Task Group 96.5 . Gunfire Support Group. |

Rear Admiral John H. Higgins, USN 1 Light Cruiser

|

___________

Close air support from Seventh Fleet; deep air support from FEAF; patrol aircraft from Task Group 96.2 .

1From Task Group 90.7

2From Task Group 90.3

32 DD from Task Group 90.4 .

Although the Pohang operation was a comparatively small one, and although plans and preparations were made in record time, the organization of the Attack Force followed standard amphibious practice. The landing force, commanded by Major General Hobart Gay, USA, consisted of the 5th and 8th RCTs of the 1st Cavalry Division, an artillery group of three battalions, and minor attached units. These were transported to the objective area in the large vessels of the transport group, in the 16 LSTs of the tractor group, and in follow-up shipping. The Attack Force also included a minesweeping group of one AM and six AMS; a gunfire suport group made up of Juneau, the American destroyers Kyes, Higbee, and Collett, and the Australian Bataan; and units assigned for reconnaissance, control purposes at the objective, administration of the beaches, and the like. Deep air support was the responsibility of the Air Force, which by this time had a fighter squadron on the Pohang air strip; close air support at the objective, should the natives prove unfriendly, would be provided by the Seventh Fleet, which was coming up from Okinawa for the occasion.

On the 14th, as the minesweepers started work in Yongil Man, the tractor group of LSTs, towing the LSUs and with two fleet tugs as escort, sailed from Tokyo Bay, to be followed on the morrow by the transport group. The route was south along the coast of Japan, then north by Bungo Strait through which Yamato, mightiest battleship in the world, had sortied on her final cruise in vain attempt to strike the American fleet off Okinawa. Turning westward through the Inland Sea, the force steamed past Shimonoseki, where almost a century before the U.S.S. Wyoming had engaged the forces of the Daimyo of Choshu, and into the Korean Strait. Early in the morning of the 18th, tractor and transport groups joined, and the ships moved into Yongil Man. Fighting had been reported only a few miles north of Pohang, but the ROK 3rd Division still held the road, and at 0559 Admiral Doyle made the signal to "Land the Landing Force" in accordance with the plan for an unopposed operation. Task Force 77 and Juneau were released from their support commitments, and only a small combat air patrol from Valley Forge was retained overhead to protect the shipping of the Attack Force.

Although peaceful, the scene at Pohang on the 18th was a busy one. From the ships of the transport group at anchor in Yongil Man, troops and vehicles were shuttled ashore. Nine of the LSTs disgorged their cargo along the jetty wall and on the beaches of Yongil Man, along with the smaller landing craft; seven were ordered out to Kuryongpo around the point to unload vehicles. Landing was begun at 0715; general unloading commenced at 0930; except for Cavalier, all major ships had been emptied by midnight, while the LSTs had discharged all personnel, all vehicles, and more than half their bulk cargo. More than 10,000 troops and 2,000 vehicles, and almost 3,000 tons of cargo had been put ashore.

There is no landing better than an unopposed landing. Since the ROK troops were still holding out to the northward, the cavalry division had been greeted at Pohang not by the enemy but by General Walker, and by trains ready-formed to carry them to the front. To some, however, this came as a disappointment. As the first sizable planned naval operation of the war, "Bluehearts" had drawn the attention of the press, and 26 correspondents were embarked in the command ship Mount McKinley. At Pohang the lack of correlation between public interest and strategic worth, always a problem for the armed services in a democracy, reappeared in the report of the public information officer that "the fact that the landing was unopposed detracted a great deal from the news value." But however saddened the scribes, the bloodless and expeditious nature of the operation was to the military a matter for rejoicing.

At noon on the 19th General Gay assumed command ashore. In the afternoon, with unloading completed, ships of the Attack Force shifted to heavy weather anchorages as Grace, the first typhoon of the season, was reported heading for Korea Strait. On the 22nd Grace came up the coast, bringing gusts of 50 knots to Yongil Man and delaying the arrival of the second echelon of shipping. This had been scheduled to come in on the 21st, but the MSTS units reached Pohang only on the 23rd, and the chartered Japanese freighters the next day. The LSTs of the third echelon arrived on the 26th and 29th.

For a variety of reasons, unloading of the follow-up shipping was somewhat slow. The MSTS transports suffered from their shortages of personnel; the Japanese freighters lacked trained hatch crews and unloading gear, and the ever-present language problem complicated supervision; after two days of continuous labor the shore party was getting tired. Nonetheless the work proceeded. On the 23rd the commanding officer of a Navy LST was directed by Admiral Doyle to take over the duties of senior officer present, and late in the evening the force commander sailed in Mount McKinley, with Union, Kyes, and Diachenko, for Tokyo. A week later it was all over, and CTF 90 was able to report the completion of operations at Pohang and the withdrawal of all shipping from Yongil Man. But this report was by way of formality, for the strategic rewards of the operation had long since been apparent. On 22 July, four days after the initial landing, the 1st Cavalry Division had relieved the battered 24th Division southeast of Taejon.

Part 4. 10–31 July: Seventh Fleet Operations

At Buckner Bay, 600 miles to the southward, Admiral Struble’s staff had been working on ways to deal with the Seventh Fleet’s Formosan responsibilities while planning with Admiral Hoskins for further carrier strikes in Korea.

In Formosa, where some expected an invasion attempt before mid-August by a force of up to 200,000, rivalries and dissension on the upper levels and low morale below raised the prospect of rapid collapse in the event of a landing in strength. Seventh Fleet control of the Strait was consequently the crucial factor; with the Seventh Fleet involved in Korea, warning of attack was essential; on 10 July, therefore, as Struble returned from his visit to Taipei, redeployment of the Seventh Fleet patrol planes was begun. VP 28, a PB4Y-2 Privateer squadron, was moved up from Guam to Okinawa; VP 46, a PBM-5 Mariner squadron with units at Sangley Point and Buckner Bay, was ordered forward to the Pescadores along with the tender Suisun; Commander Fleet Air Wing 1 was relieved of responsibilities at Guam and instructed to advance his headquarters to Okinawa.

These movements were expeditiously completed. Captain Grant had his wing headquarters in operation at Naha Air Force Base by the 15th; on the next day VP 28 began daily patrols of the China coast and northern Formosa Strait; by 17 July VP 46 was flying searches in the southern sector. On the basis of this forward deployment Commander Seventh Fleet proposed on the 16th that General MacArthur announce the imminent commencement of naval air reconnaissance of Formosa Strait. The proposal was approved the same day, and having brandished the weapon of publicity against the Chinese Communists, Admiral Struble sailed from Buckner Bay to employ his Striking Force against the North Koreans.

In Korea his presence was urgently desired. On 9 July General Dean, then commanding all Army units in Korea, had inquired hopefully about the possibility of carrier air support. In response Struble next day advised Admiral Joy of his willingness to help out either with close support or with further strikes on west coast targets, while noting that until ammunition reached Okinawa on the 18th he would be limited to two days of close support operations. For effective work in support of troops the front line communications problem was governing; if the Tactical Air Control Squadron from Mount McKinley could be made available, all would be well; if not, Seventh Fleet could supply a small control team, although equipment would have to be provided it. Subject to these considerations Struble proposed to sail from Buckner on the 11th for operations on the 13th and 14th.

The offer, however, was not accepted. Admiral Joy’s reply stated that he knew of no plans for carrier close support, and that the Tacron was not designed for shore employment. The limitations on Seventh Fleet endurance, moreover, made him want to hold it in reserve to cover the landing of the 1st Cavalry Division, and on the 12th a dispatch operation order instructed Admiral Struble to provide objective air cover at Pohang, support of the landing force, and such additional effort as might be directed. Two days later Struble again flew to Tokyo for talks with Admiral Joy and General Stratemeyer; a schedule was worked out which called for two days in support of the landing and in northward strikes against the enemy, a day for replenishment, and two more days of operations; an east coast area was cleared with FEAF for strikes on the 18th and 19th. On 16 July, as the Seventh Fleet started north to cover the Pohang landing, Admiral Joy issued Operation Order 10-50 governing the conduct of carrier attacks against the North Korean forces.

The planning for these operations had seen the emergence of the first of a series of problems concerning carrier employment which was to trouble naval commanders throughout the campaign. So far as support of the Pohang landing was concerned there was no difficulty: this was a conventional naval task in which all hands felt quite at home. But attack on the North Korean forces and installations beyond the beachhead raised problems of coordination with the Air Force. Subsequent to the first carrier attack on Pyongyang, General Stratemeyer had requested the Seventh Fleet to confine its further strikes to northeastern Korea, north of the 38th parallel and east of 127° E, with target priorities beginning with rail and highway cuts and running down through petroleum facilities to airfields. Yet such an employment of carrier aviation, however desirable in the situation of the moment, was certainly not envisaged in the existing unification agreements. The roles and missions papers for the armed forces, worked out during the painful period of unification, made interdiction of enemy land power and communications an exclusive Air Force function in which the Navy could participate only after a complicated bureaucratic procedure of authorization. The fact that naval air was not to be so used had been one of the reasons advanced in support of the cancellation of construction of the carrier United States.

It had, of course, been recognized that in an emergency the instruments at hand and the urgency of the situation would take precedence over paper agreements. But there was the further difficulty that the employment of carrier aviation in interdiction was not contemplated in current naval thinking. On the one hand the interdiction of land communications calls for continuous effort; on the other, it was felt that logistic considerations and the dangers of air and submarine attack made it undesirable for carriers to operate for more than two days in the same location. By autumn, when concern over air and submarine opposition had greatly subsided and when underway replenishment had improved, the carriers would be operating for protracted periods in the same locality. But autumn was far away, and in the intervening period of emergency things would become worse before they became better.

This triple conflict between legislation, doctrine, and the exigencies of the situation was to prove the less manageable owing to difficulties in coordination with the Air Force. Although these, stemming both from doctrinal differences and from technical difficulties in communication, were never to be completely solved, some steps had already been taken. On 8 July General Stratemeyer had advised CincFE that it was essential that he have "operational control" of all naval aircraft in the theater. To the Navy, quite apart from doubts as to FEAF’s technical capability to handle this effort, the implications of the request appeared excessive, involving as they did the authority to control carrier movements as well as to assign targets, and after some discussion a CincFE letter of the 15th delegated "coordination control" to the commanding general of FEAF. It was on the basis of this agreement that Struble had cleared with FEAF his plans to strike northward from Pohang and that Joy issued his operation order of 16 July.

Morning of the 18th found Valley Forge, Triumph, and their screening ships in the southern Sea of Japan, some 60 miles northeast of Pohang. At dawn local antisubmarine and combat air patrols were launched by Triumph, and Valley Forge sent off a target combat air patrol and a support group of attack planes to assist the landing. No alternative targets seem to have been given the support group; the location of the front line and the needs of the ROK 3rd Division were apparently unknown; and when the landing proved unopposed and the task force was released from its air commitments the support group jettisoned its load.

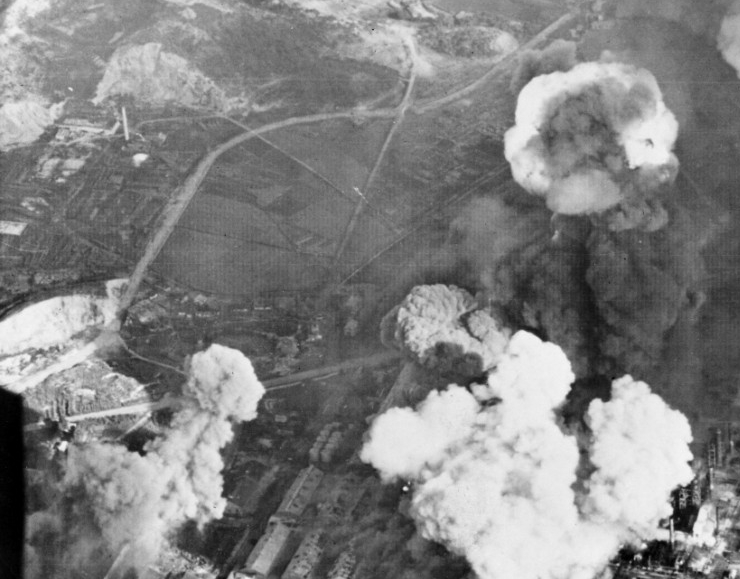

Except for the requirement of a combat air patrol over Pohang, the Valley Forge air group was now available for attacks on North Korean targets. On the 18th and 19th, therefore, strikes were flown against railroad facilities, industrial plants, and airfields from Pyonggang and Wonsan north through Hungnam and Hamhung. In the two days of attacks two aircraft were lost, but both pilots were recovered. About 50 grounded aircraft were sighted, of which more than half were destroyed and the remainder damaged, while flights north along the railroad on the 19th exploded four locomotives. But the biggest explosion was at Wonsan.

This seaport city, located at the head of the Korean Gulf and at the east coast focus of Korean rail communications, had grown rapidly under the Japanese regime. Its population, now of the order of 150,000, had tripled within a generation. It was the site of a number of manufacturing plants, and the center of a considerable complex of petroleum installations, developed to support Japanese continental expansion, which included the largest refinery in Korea. Following the arrival of the Russians in 1945 this refinery had for some time been inactive, but in 1947 a joint Russian-North Korean enterprise had been formed to operate it, Soviet supervisors had been provided, and late in the next year crude oil began to arrive in Soviet tankers for processing.

On the afternoon of the 18th Valley Forge jets reported that the refinery appeared in full operation, and at 1700 a strike group of 11 Skyraiders and 10 Corsairs was launched, the former armed with 1,000 and 500-pound bombs and the latter with high velocity aircraft rockets. As the group came in over the city the Corsairs went down first, firing their rockets and 20-millimeter guns, and were followed by the ADs with their bombs. The results were spectacular, with large fires and so much smoke that photographic damage assessment was difficult. On the next day a Valley Forge flight passing in the neighborhood observed the refinery still burning vigorously, while the smoke, rising to 5,000, was visible to the force at sea.

The attack on the Wonsan refinery gave rise to an interservice conflict of claims. Air Force planes had attacked the city between 6 and 13 July. There then followed the carrier attack of the 18th, on the basis of which the Navy reported the destruction of the refinery. On 10 August another heavy raid was made by B-29s, after which a FEAF communique claimed total destruction of the refinery, which had been attacked on the basis of "reconnaissance photographs [which showed] that only a small portion... had been damaged in the previous small air strikes."

Interrogation of supervisory personnel by Marine Corps officers in the autumn elicited the statement that although the early raids had had adverse effects on employee morale, and had stimulated the removal of bulk petroleum products, no bomb had hit in any vital area. The Valley Forge attack of the 18th was reported to have destroyed 12,000 tons of refined products, saturated every vital area in the refinery, and caused it to be declared a total loss. What remained of the plant had been flattened by the bombing of 10 August, and in early October, as ROK forces approached Wonsan, the Russian supervisors had headed north for the border.

Apart from the question of who hit what, the strikes of 18 and 19 July raise questions as to target selection in a police action. The objectives were, of course, in accordance with the desires expressed by FEAF concerning attacks by Seventh Fleet aircraft on North Korean targets. But the aspect of strategic air warfare which emphasizes attack on industrial plant is slow to have effect at the battleline; the real strategic targets were outside Korea, and destruction of North Korean facilities as of this date would seem merely to have promised difficulties in reconstruction, assuming U.N. success in the campaign. Overshadowed though it was by the refinery quarrel, it seems probable that the destruction of grounded aircraft by the Valley Forge air group was the most important result of the two-day operation; together with some similarly successful sorties by Air Force jets on the 19th, this pretty well liquidated the North Korean Air Force. But habits are hard to break, and just as the carrier commanders were reluctant to undertake continuous operations in the same area, so others found it difficult to divest themselves of strongly held notions on air warfare; on 31 July a message from the Joint Chiefs urged the strategic bombing of North Korean industrial targets.

It may be conceded, in this context, that the case of the Wonsan refinery is not entirely clearcut. Despite the handcarrying nature of the North Korean army the destruction of 12,000 tons of petroleum products may have had valuable consequences, so great is the importance of oil to modern war. And inevitably, the course of the Korean conflict being what it was, the policeman’s attitude developed into that of the warrior. But in these early weeks, at least, it would seem that the police action should have been conducted as such. Rioters are quelled with nightsticks, not by turning off the gas and water at their homes. Had it been possible in the early days to deliver, in accordance with Army desires and naval capabilities, well-controlled and well-coordinated close air support at the front, the effect on the ground situation would have been more immediate. It was on the ground that the emergency lay.

Two days of east coast strikes had gone off well, but nature now intervened to change the schedule. Concerned by the time involved in commuting between Okinawa and the scene of action, Commander Seventh Fleet had been expediting arrangements for underway replenishment and was contemplating a shift of base forward to Sasebo; the plans of the moment called for the force to fuel at sea on the 20th in preparation for two more days of operations. But the approach of Typhoon Grace forced postponement, and with completion of flight operations on the 19th all ships set Typhoon Condition One and prepared for the worst in the way of weather. On the 20th, in winds of up to 40 knots, the force cruised the Sea of Japan, and late in the day headed south through Tsushima Strait to get clear of Grace’s skirts and gain an operating position off the west coast of Korea. On the 21st Triumph was detached with Comus for a ten-day period of availability at Sasebo.

Admiral Struble had advised ComNavFE on the afternoon of the 20th that he hoped to conduct a one-day strike on west Korea on the 22nd, spend a day in refueling and rearming his force, and return on the 24th and 25th for further attacks against west coast targets. But this schedule depended on factors beyond his control, on weather and on the availability of replenishment ships. The tanker Navasota was by this time on hand to fuel the force, but for rearming the situation was less clear, and depended on whether the AK Grainger, which had reached Okinawa on the 18th with a load of aircraft ammunition from Guam, could rearm the force at sea. Failing in this it would be necessary to proceed to Sasebo, with consequent delay.

At dawn on the 22nd, from a location in the Yellow Sea northwest of Kunsan, Valley Forge launched her air group. Although his force was now down to a single carrier, Struble undertook the double mission of support of troops and attack on northern targets: the propeller-driven ADs and F4Us were sent off to the eastward to work under airborne controllers from Fifth Air Force in close support of the ground forces; the jets headed north to attack targets beyond Seoul. The air support mission, first of the Korean War, went awry as the strike aircraft, unable to reach the controllers on the prescribed radio frequencies, resorted to attacks on secondary targets in the area of the capital. In the afternoon a second effort met with similar results, and after recovery of the strike group the force headed southward to rendezvous with Navasota. By this time Valley Forge was down to a little less than a one-day supply of aviation gasoline.

Rendezvous with the tanker was made late in the morning of the 23rd to the southward of Cheju Do, but Grainger and the ammunition were not there. On completion of refueling, therefore, Task Force 77 headed for Sasebo where it arrived on the morning of the 24th. The delay in resuming operations, which Admiral Struble had feared, had been forced upon him.

In the meantime the events of the 22nd had prompted a review of the mission of the Seventh Fleet. The waste of effort consequent to the inability of his strike groups to reach the controllers had led Struble to look for more profitable employment elsewhere. Casting his eyes northward, he proposed to ComNavFE a change of schedule which would call for two days of strikes against east coast targets from Chongjin southward, coupled with cruiser and destroyer bombardment between 40° and 41°, and asked for detailed target information. But by this time a new emergency was developing in Korea. The Pohang landing had been successful, the main front had been reinforced, but west of the central hill mass the advance of the North Korean 6th Division had continued unopposed. The entire southwestern region had been overrun, and the invaders were moving eastward with nothing to block their path. On the 23rd, while Valley Forge was refueling, an emergency dispatch from Eighth Army advised all major commanders that an "urgent requirement" existed for the employment of naval air in the west coast area beginning that very day, and requested information as to naval capabilities in close and general support.

From both Joy and Struble this dispatch brought prompt reply. The former observed that subject to the primary mission of the neutralization of Formosa, and to the undesirability of protracted operations in one spot, no great difficulty was expected in coordinating Seventh Fleet and Air Force operations, provided only that successful joint communications were established. But to Commander Seventh Fleet the situation appeared more complicated. While observing that Eighth Army’s urgent requirement could be met beginning on the 26th, he emphasized the fact that present methods of coordination were unsatisfactory, and that in addition to the communications problem there was an urgent requirement for personnel trained in the control of close support aircraft. To fill this need Struble repeated his proposal of 10 July that either the Tactical Air Control Squadron from Admiral Doyle’s Amphibious Group be sent to Korea, or that the Seventh Fleet itself supply a small but experienced control team.

The need for some competent control group to handle close support had already received consideration. Four days earlier EUSAK—Eighth U.S. Army in Korea—had requested that the Anglico which had been attached to the 1st Cavalry Division for the Pohang landing be assigned on completion of that operation to assist the Joint Operations Center in control of naval gunfire and naval air. The request had been approved by Admiral Joy’s headquarters, and Admiral Doyle was so instructed on the 20th. But by then the Anglico was returning to Yokohama by sea, and by the time of its arrival it had come to seem more profitable to retain it in Japan to train Army and Air Force personnel.

So things stood when the crisis in the west and Eighth Army’s call for help led Struble to renew his suggestion for the employment of the Tacron or of a Seventh Fleet control party. These proposals also were to prove abortive. The plan for the Seventh Fleet tactical air control party, worked up at Buckner Bay, had contemplated a pooling of Valley Forge and Triumph material and personnel, but the sortie on the 16th had interrupted preparations. The recommended employment of the Tacron was vetoed at the instance of Admiral Doyle, who felt its personnel would be spread unprofitably thin. The upshot was that efforts to increase the yield of carrier operations in close support were limited to attempts, themselves badly needed, to improve radio communications between the Seventh Fleet Striking Force and the JOC.

At Sasebo rearming of Valley Forge had begun on the morning of the 24th. But replenishment was to be cut short by the rapid deterioration of the ground situation in the west. Early in the afternoon an emergency dispatch was received from ComNavFE, cancelling existing plans and assigning Task Force 77 the area south of the Kum and west of the line Kunsan-Chonju-Namwon-Kwangju. This region was believed to contain a major concentration of North Korean forces; according to the dispatch the "total area is considered enemy." Commander Task Force 77 was adjured to search carefully and to destroy all armor, bridges, traffic, troop concentrations, and barges up to the limit of his capabilities. The only restrictions on his operations were to beware of Korean Navy YMS types operating inshore, and to "hit only military targets" at Kunsan, where preservation of port facilities seemed desirable in view of possible future amphibious operations. As the dispatch emphasized the critical situation of the ground forces and urged immediate efforts, Valley Forge broke off her rearming before completion, and Triumph, whose yard period had barely begun, rejoined the force. At midnight on the 24th Task Force 77 was again underway from Sasebo, headed north.

The carriers launched at 0800 on the 25th from a position south of Korea, and for the remainder of the day maintained planes in the air over the front line. Once again, however, results were disappointing; pilots returning from the morning strikes reported that air controllers had more planes than they could handle and that radio channels were overcrowded; these factors, together with the lack of common charts and procedures, had prevented controlled attacks, with the result that the "free opportunity" area assigned in the west had been liberally used to dispose of ammunition.

Early in the afternoon Admiral Struble reported that owing to lack of targets the morning sweeps had been of very minor effect. In point of fact it appears that ComNavFE’s intelligence was stale, and that the North Korean 6th Division had by this time passed through the country assigned the carriers and was concentrated about Sunchon. The region so menacingly described in the emergency dispatch from Admiral Joy turned out to be a peaceful agricultural area populated principally by donkey carts and men working in rice paddies. Although he announced that he would continue with afternoon attacks, the effort seemed unfruitful to Commander Seventh Fleet, and once again he emphasized the need of proper communications with commanders in the field.

In view of the unproductive nature of the day’s work the Valley Forge air group had flown pilots to Taegu to arrange for targets and communications for the 26th. The result was an assignment to close support at the front, attack on miscellaneous targets as directed by the Joint Operations Center, and deep support strikes in the region between Taejon and Seoul. In the evening these intentions were reported by Commander Seventh Fleet to ComNavFE, and the Striking Force turned northeast and headed for the Korean Strait and for a morning position off Pohang.

Admiral Struble’s dispatch stating his plans for 26 July produced an immediate howl from Tokyo. No new area for carrier operations had been arranged with FEAF headquarters in Japan, and Admiral Joy requested immediate information as to Commander Seventh Fleet’s intentions. Prior to the 25th arrangements for carrier strikes had been made on the upper levels, between ComNavFE and the commanding general of FEAF, on a basis of general area coordination, but with the commencement of efforts to use carrier planes in support of troops this system began to break down. Struble’s reply described the arrangements which had been made directly with EUSAK and JOC, and since difficulties were still being experienced in direct communication, followed up with a request that ComNavFE clear with FEAF for operations as far north as Suwon. On the 27th a message from ComNavFE implicitly endorsed the procedure of coordinating operations with the JOC in Korea, and from this time on such coordination was increasingly attempted.

Within the force, morning of the 26th was marked by an extremely convincing submarine contact, but the early strikes led to little more than the destruction of some trucks on the enemy main line of communications. But in the afternoon, despite congestion of aircraft in the target area, one flight of four ADs at last found adequate control. The result was the reported destruction of 70 percent of Yongdong, a junction town just west of the saddle where two highways and the railroad come together, and two later flights of eight Corsairs applied more effort to this pressure point by striking troop concentrations in the region between Yongdong and Taejon.

On conclusion of the operations of the 26th, which at least represented some improvement over earlier efforts in suport of Eighth Army, the task force withdrew to refuel. CincFE had expressed his enthusiasm over the effect of the carrier air attacks, and on the 27th the Fifth Air Force JOC, after politely describing the attacks of the 26th as "invaluable and much appreciated," inquired as to their results, requested information as to future operations, and stated it could handle as many flights as could be provided. But a report from Admiral Doyle on the state of Army and Air Force control of tactical air seemed to indicate a need for basic reorganization and training before adequate standards could be obtained, while the Seventh Fleet, despite the compliments, remained unsatisfied with the results of its work.

By now, too, there were signs that a crisis was making up in Formosa Strait. On the 21st a reported sighting of between 500 and 1,500 junks by the master of a British merchantman had led to special searches by Fleet Air Wing1. These proved negative, but on the 26th a VP 28 patrol plane was attacked by two fighters in the northern part of the Strait. In this situation, and as continuation of the support effort seemed of doubtful value, Struble recommended to ComNavFE that the Seventh Fleet move south to the Buckner-Formosa area for a possible sweep of the Strait.

This proposal, however, was disapproved. The needs of Eighth Army remained paramount, other units were dispatched to the southward, and on 28 July Task Force 77 returned to the attack, operating in the area northwest of Mokpo. The strikes of propeller-driven aircraft on the 28th were again concentrated around Yongdong, and in the neighborhood of Hamchang at the northwest corner of the perimeter. Attacks were made on troop concentrations, trucks, and tanks, and although one jet flight to the Naktong River front failed to contact a controller and returned without result, control arrangements were reported somewhat improved.

In an attempt to make them even better, by improvement of communications between the task force and the JOC and by simplification of the complicated control procedures then in effect, another mission was flown to Taegu. This visit bore fruit in the establishment of a direct communications link, and helped to minimize some operating problems by making JOC personnel aware of what the carrier force could and could not do. The previous overloading of airborne controllers was partially rectified by the assignment, for the 29th, of a defined section of the front line and of specific Mosquito aircraft to the planes of Task Force 77. Within the force, with similar ends in view, another move to organize a tactical air control party with Valley Forge and Triumph personnel had begun, but the early permanent detachment of the British carrier was to prevent fruition.

On the 29th the Corsairs and Skyraiders shifted their efforts to the Hadong-Sunchon region of the south coast, from which a battalion of the 29th Regiment, moved west from Pusan to block the passage south of the central hill mass, had just been driven by the North Korean 6th Division. Here pilots reported destruction of a score or more trucks and a couple of tanks and damage to bridges and rolling stock, and described control procedures as varying from very good to very bad. To the northward, on the Naktong River front, a morning strike of eight Panther jets found a controller who was at least frank to admit that he was overloaded and could not work them; four were detached on armed reconnaissance to the northward while the others, although unable to make radio contact, showed their initiative by following an F-8o flight in a strafing run on enemy troops.

With the end of the day’s operations the Striking Force retired. Carrier operations during July, limited though they were by logistic problems and frustrated by difficulties in control, had been reasonably successful, but they had not been free from cost. In addition to the aircraft destroyed in the deck crash of 4 July, two F9Fs, three F4Us, and a helicopter had gone into the water, and on the 22nd an AD had crashed and burned, taking its pilot down with it. Most downed personnel, however, had been fished out of the sea by screening ships; one pilot had been recovered 80 miles from the force by Triumph’s amphibian plane; another, shot down behind enemy lines, had been picked up by an Army helicopter which in turn had gone down from fuel exhaustion, but both pilots ultimately had made contact with friendly forces. Perhaps the most remarkable loss of the period had occurred on the 28th when a Triumph fighter pilot on combat air patrol, vectored out to investigate a radar contact which showed unfriendly, had somewhat absentmindedly closed a B-29 only to find himself shot down west of Anma Do in the Yellow Sea. But he too was recovered by a destroyer.

Following the operations of the 29th five ADs were launched with pilot passengers to pick up replacement aircraft which had reached Japan in Boxer; Triumph and Comus were detached to Japan for further assignment to the west coast blockading force; Admiral Struble boarded a destroyer and headed for Sasebo in anticipation of a flying trip to Formosa with CincFE; Valley Forge and her screen steamed south for Buckner Bay. There they anchored on the 31st and there, on the next day, Task Force 77 received a welcome accession of strength with the arrival of the carrier Philippine Sea.

Part 5. 7 July–2 August: Patrol Planes and Gunnery Ships

Through the hectic weeks of July, as the U.N. Command struggled to stem the enemy advance, naval operations fell into three interrelated categories. To support the campaign in the peninsula a steady stream of shipping was flowing into Pusan, while the Pohang landing, carried out by Task Force 90, permitted the rapid reinforcement of the front by the previously uncommitted 1st Cavalry Division. At the same time Task Force 77, the U.N’s long-range weapon, worked over North Korean air strength and communications, attacked targets of opportunity like the Wonsan refinery, and attempted to support the western front against the pressure of the numerically superior enemy. As troops and supplies were fed into Korea, and as Struble’s force struck northward and struggled with problems of communications and control, the units of Naval Forces Japan were busy on both sides of the peninsula. While patrol planes covered the maritime flanks, the gunnery units escorted shipping, bombarded enemy positions, and gave fire support to the ROK forces holding the east coast road.

Like everyone else, the Fleet Air Wing 1 detachment had more jobs than it could easily handle. To perform the multitudinous duties of antisubmarine patrol, escort of convoy, weather reconnaissance, and shipping search, Captain Alderman had a total of eight PBM Mariner flying boats and nine P2V Neptunes. Shortly after their arrival in Japan the PBMs of VP 47 moved from Yokosuka to the RAAF base at Iwakuni, near Hiroshima on the Inland Sea. Messed, housed, and supported by the hospitable Australians, the squadron managed to extemporize a seadrome and to maintain an antisubmarine patrol of the Korean Strait, and on the 15th the arrival of the seaplane tender Gardiner’s Bay brought more ample logistic assistance.

Meanwhile the Neptunes of VP 6, which had reached Japan on 7 July and were operating out of Johnson Air Force Base at Tachikawa, were flying daily reconnaissance of the Korean east coast between 37° and 42°, and of the Yellow Sea and west coast as far north as 39°30'. But the lack of enemy seaborne traffic made the flights unproductive, while coordination with surface units was hindered by the remoteness of Johnson AFB from other naval activities. There were also certain difficulties in communications; on 20 July a VP 6 pilot spent three hours inside Typhoon Grace looking for a convoy he had been instructed to escort, only to discover on his return that the weather had kept the ships in port. On the 29th, however, the opportunities open to the Neptunes were enlarged by authorization to attack enemy shipping and installations, and two at once complied by destroying, with rockets and 20-millimeter fire, a train on the east coast line near Chongjin.

The arrival of Rear Admiral Ruble, Commander Carrier Division 15, and of his staff, enabled Admiral Joy to rationalize his air command. The Search and Reconnaissance Group was united with the other naval aviation activities in a new command, Naval Air Japan, which assumed responsibility for squadrons, aircraft, logistics, and bases. But while this improved the administrative situation, it in no way lightened the load for the 17 patrol planes and their crews, and when at the end of the month three RAF Sunderland flying boats reached Iwakuni from Hong Kong, they were most welcome.

On the east coast, day after day, bombardment of the enemy invasion route continued. Coordination with the troops ashore was improving steadily, Korean interpreters had been assigned the ships, an artillery officer had been attached to Admiral Higgins’ staff, and spotting planes were at least intermittently available.

On 18 July, as the 1st Cavalry was landing at Pohang, Mansfield and De Haven were working the coastal road in the vicinity of Samchok, while Belfast and Cossack were patrolling at the 38th parallel. In the morning, as Juneau was released from her support commitments, the others came south to join the flagship off Yongdok, where the day was spent firing on targets of opportunity and where a reported "full-scale" enemy offensive was broken up. In the afternoon, parties of American and British naval officers went ashore to confer with the KMAG group attached to the ROK 3rd Division and to pass out radio sets in the interest of improved communications. That evening Admiral Higgins instituted a new technique, and while the main body operated off the battleline a single destroyer was detached nightly to prowl northward along the coast, seeking out and shooting up promising targets.

For the next two days Juneau, Belfast, and the destroyers operated off Yongdok, between 36° 17' and 36°30', and although the spotting planes were grounded by the passage of Grace, the gunners’ efforts met with great success. Two days of shooting up the valley at troop concentrations in Yongdok cost the ships some 1,300 rounds and got them a radio station, more than 400 enemy troops "by actual count," and enthusiastic reports from the shore fire control personnel.