Salmon II (SS-182)

1938–1945

A soft-finned, gamy fish which inhabits the coasts of America and Europe in northern latitudes and ascends rivers for the purpose of spawning. Salmon are highly valued for their rich, succulent meat.

II

(SS-182: displacement 1,435 (surface), 2,198 (submerged); length 308'; beam 26'1"; draft 14'2"; speed 21 knots (surface), 9 (submerged); complement 55; armament 1 3-inch, 2 .50 caliber machine guns, 2 .30 caliber machine guns, 8 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Salmon)

The second Salmon (SS-182) was laid down on 15 April 1936, at Groton, Conn., by the Electric Boat Co.; launched on 12 June 1937; sponsored by Miss Hester Laning, daughter of Rear Adm. Harris Laning (Ret.); and commissioned on 15 March 1938, Lt. Marvin M. Stephens in command.

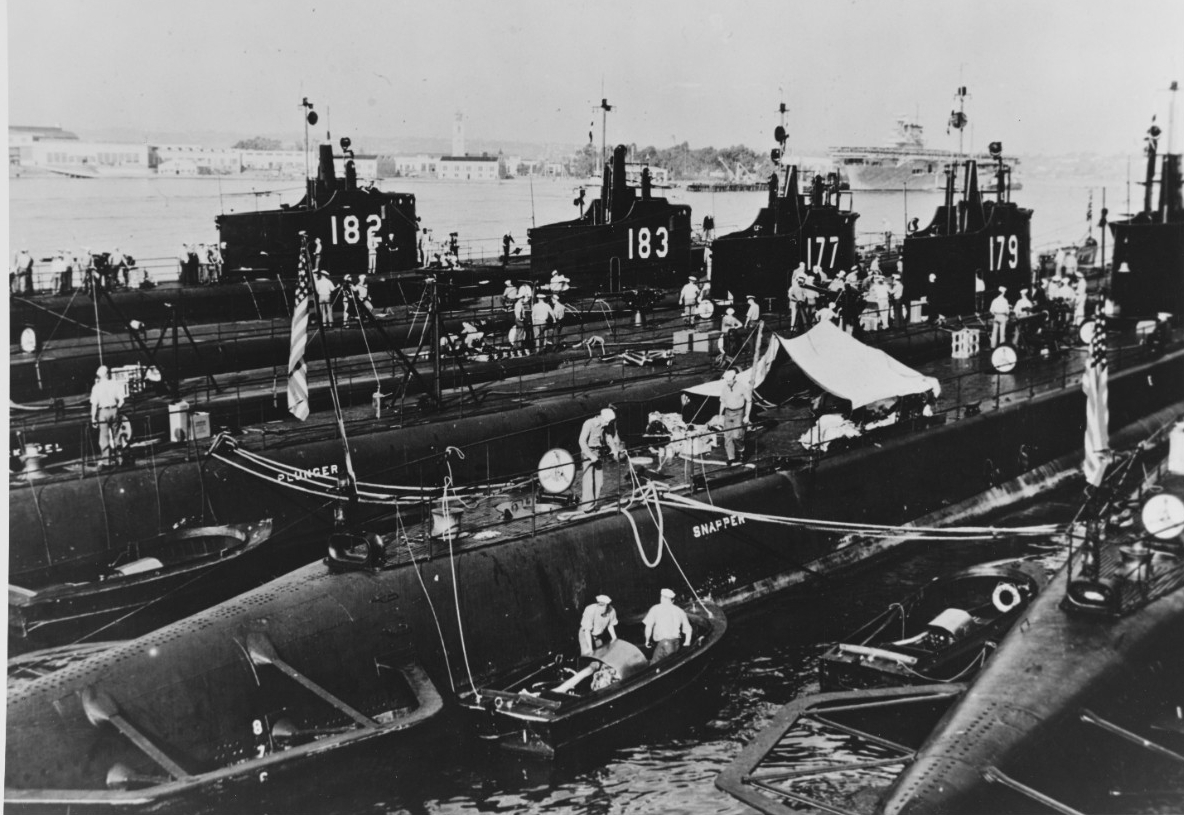

Following her shakedown training and trials along the Atlantic coast that ranged from the West Indies to Nova Scotia, Canada, Salmon joined Submarine Division (SubDiv) 15, Squadron 6, of the Submarine Force, U.S. Fleet, at Portsmouth, N.H. As flagship of her division, she operated along the Atlantic coast until she relinquished the broad pennant to Snapper (SS-185) late in 1939, as the division shifted to the Pacific Fleet at San Diego, Calif. Salmon operated along the west coast through 1940 and the greater portion of 1941. Late that year, she was transferred with her division and submarine tender Holland (AS-3) to the Asiatic Fleet. On 18 November, Holland, Salmon, Skipjack (SS-184), Sturgeon (SS-187), and Swordfish (SS-193) arrived at Manila and the boats served as SubDiv 21 to bolster U.S. and Filipino defenses in the Philippines.

Less than a fortnight after Salmon and her sisters stood in to Manila Bay, Adm. Harold R. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations, sent a “War Warning” message to the commander in chiefs of the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets on 27 November 1941, a day after Dai-ichi Kidō Butai (the Japanese 1st Mobile Striking Force) sailed from Japanese waters to attack Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. Salmon consequently patrolled from Manila along the west coast of Luzon and toward the waters off Formosa [Taiwan] in what some of her crewmen referred to as a “wait-and-watch posture”. When the Japanese attacked on 8 December 1941 [west of the International Date Line] -- Adm. Thomas C. Hart, Commander in Chief Asiatic Fleet, sent a terse but chilling priority order to the fleet: “Japan started hostilities govern yourselves accordingly.” Salmon came about and on 10 December returned to Manila to prepare for her first war patrol.

Salmon experienced her first action while attempting to top off with provisions and water at the Cavite Navy Yard that day. Cmdr. Eugene B. McKinney, the commanding officer, went ashore to obtain the operations order but at least 54 Japanese land attack planes of the Takao Kōkūtai and 1st Kōkūtai [Air Groups] bombed Cavite. The Japanese flew at 20,000 feet, just above the maximum range of the nine U.S. 3-inch antiaircraft guns that vainly fired and attempted to defend the station, and the enemy practically obliterated the yard. Winds fanned the flames into an inferno that all but consumed the navy yard and thee town, and killed and wounded hundreds of Americans and Filipinos.

The Japanese bombs and fragments destroyed ferry launch Santa Rita (YFB-681) and damaged destroyers Peary (DD-226) and Pillsbury (DD-227), submarines Seadragon (SS-194) and Sealion (SS-195), and submarine tender Otus (AS-20), while fires gutted minesweeper Bittern (AM-36). Submarine rescue vessel Pigeon (ASR-6) towed Seadragon out of the burning wharf area, and minesweeper Whippoorwill (AM-35) recovered Peary, enabling both warships to be repaired and returned to service. While the Japanese bombed the Manila Bay area they also damaged unarmed U.S. freighter Sagoland.

Bombs and fires also tore into the power plant, dispensary, warehouses, barracks, radio station, supply office, and officer’s quarters. More ominously for the submarines, the attack struck the torpedo repair shop and also destroyed 230 torpedoes. Salmon’s deck force cast off her mooring lines and the boat slipped out into the harbor to escape the bombing. Adm. Hart somberly watched the raid from the roof of the Marsman Building [where he had his headquarters], and the following day conferred with Rear Adm. Francis W. Rockwell, Commandant of the Sixteenth Naval District and Commander of the Philippine Naval Coastal Frontier, and they agreed to salvage what they could from the disaster, but the Japanese had struck a telling blow almost from the outset.

Later that day Salmon returned and retrieved McKinney. The bombing, however, had delayed the boat from topping off as originally planned because of the necessity of passing through the minefield at the approaches to Manila Bay before nightfall. Consequently, Salmon began the war with an estimated 60 days of provisions. McKinney and his crew did not anticipate patrolling for that length of time without being resupplied, and at first did not curtail their regular meals. As their patrol continued, however, they reluctantly rationed their food, and eventually ran out of many provisions including coffee, milk, and sugar.

Three Japanese convoys comprising an estimated 76 transports and auxiliaries, meanwhile, carrying soldiers of the 14th Army, Gen. Homma Masaharu in command, rendezvoused off Lingayen Gulf and landed elements of the 16th and 48th Infantry Divisions and 4th and 7th Tank Regiments on those beaches on 21 and 22 December 1941, covered, at intervals, by ships of the Second Fleet, Vice Adm. Kondō Nobutake in command, and the Third Fleet, Vice Adm. Takahashi Ibō. One of the U.S. submarines patrolling the area, Stingray (SS-186, sighted some of the enemy ships on 21 December and alerted the Asiatic Fleet to their approach. Adm. Hart dispatched Saury (SS-189), Salmon, S-38 (SS-143), and S-40 (SS-145) to reinforce Stingray. By the time the submarines reached the area, however, many of the enemy ships maneuvered into shoal waters that rendered submarine attacks problematical.

Salmon, charging her batteries while surfaced at about midnight on 22–23 December 1941, sighted a vessel on the horizon, and about 30 minutes later lookouts identified a pair of destroyers approximately 5,000 yards away, closing at low speed and maneuvering to keep their bows headed into the submarine’s stern. As the ships closed to about 2,500 yards, one of the destroyers presented a broad beam, and Salmon fired a brace of torpedoes in what McKinney later described as a “down the throat” attack, but they missed. Both of the Japanese ships turned toward the submarine and closed the range to just over 1,000 yards. Salmon fired another pair of torpedoes and crash dived. Some of the Americans believed they heard one or more explosions, and they eagerly hoped that they had blooded the enemy at the outset of the war.

The destroyers clung tenaciously to their prey, however, and Salmon’s sound operator reported that he heard a set of screws churning at high speed astern of the boat and then stopping. The submariners waited an hour and then cautiously surfaced to investigate the results of their attack and gratefully breathe fresh air, but both of their torpedoes had missed — and within mere minutes of surfacing the sound operator again heard screws turning up off the port quarter. The lookouts gazed into the haze for several tense minutes and then suddenly sighted a destroyer closing, and Salmon quickly dived again as the ship passed almost overhead.

The Japanese destroyermen proved persistent and dropped depth charges seven times while the submarine conducted evasive movements to survive. Finally, at 1630 the attacks ceased and Salmon broke the surface and ducked into a rain squall. Later that night the submarine recharged her batteries and resumed the war patrol. McKinney subsequently received the Navy Cross for his “experience and sound judgment” while in command of Salmon during her first war patrol, citing that his “conduct throughout was an inspiration to his officers and men and in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Less than a week later, while again surfaced to recharge her batteries, Salmon abruptly encountered a large number of ships that appeared off the bow to port and starboard, running nearly parallel courses. Salmon immediately changed to battery power and attacked, her deck practically awash. The boat fired four torpedoes from her bow tubes but missed, and the enemy detected the intruder and began depth charging, two of which exploded close aboard and caused superficial damage. The noise of the detonations prevented the Americans from hearing any of their torpedoes from striking, but as the submarine understatedly later reported, they were “more interested in getting out.” After several nerve-wracking hours Salmon surfaced and recharged her batteries.

The Japanese rapidly thrust southward and in January 1942, Salmon moved south to operate in the Gulf of Davao and off the southern tip of Mindanao. From there she proceeded to Manipa Strait between Buru and Manipa Island -- Ceram [Seram] -- in the Moluccas Islands of the Netherlands East Indies [N.E.I. — Indonesia]. The following day, she patrolled the Flores Sea from north of Timor to Lombok Strait between Bali and Lombok in the N.E.I.

Salmon moored alongside oiler Trinity (AO-13) in the congested port of Tjilatjap, Java, on 13 February 1942. The submarine had been damaged by the Japanese depth charge attacks and suffered a multitude of problems as a result of the pounding she had taken during the voyage. Her ventilation system had repeatedly failed, which proved a burden for her men in the sweltering tropics, and the boat desperately required fuel, provisions, ammunition, and spare parts. Salmon set out a week later and after five days at sea experienced an inclusive brush with a group of enemy warships and merchantmen. The Americans fired torpedoes unsuccessfully and escaped the all but inevitable and terrifying depth charges.

The relentless Japanese onslaught and Allied losses compelled the abandonment of Surabaja as a base, and thus exposed Tjilatjap as a possible trap. Holland moved her base of operations to Exmouth Gulf in Australia on 20 February 1942, as Salmon set out on her second war patrol. Salmon spent the next few weeks in the Java Sea patrolling between Sepandjang and the area just west of Bawean. The submarine sighted the 4,468 ton Japanese transport Taito Maru north of Lombok near 05°35'S, 112°35'E, on 13 March. At 2300 McKinney fired two torpedoes, one of which damaged Taito Maru but she continued her voyage. Salmon unsuccessfully attacked two other enemy ships during the cruise, and during one such attack, McKinney coolly and skillfully evaded enemy countermeasures, for which he later received a letter of commendation. The veteran boat ended her second patrol at Fremantle, Australia, on 23 March.

Beginning her third war patrol, Salmon departed from Fremantle on 3 May 1942 and established a barrier patrol along the south coast of Java to intercept Japanese shipping. On 25 May, the submarine detected what the crew initially believed to be a ship that displayed a profile similar to light cruiser Yūbari, escorted by a pair of destroyers. Salmon actually tracked 11,441-ton repair ship Asahi for nearly an hour until she maneuvered into an adequate firing position, and then launched a spread of four torpedoes that sank the auxiliary about 180 miles south-southeast of Cam Ranh Bay, French Indochina, near 10°00'N, 110°00'E. The boat dove to 200 feet and rigged for a depth charge attack from the two escorting destroyers, which only briefly dropped their lethal devices before sailing from the scene of the battle. The Americans subsequently reported that they meanwhile heard “loud water agitations…in the bearing of the target,” and thus believed that they had indeed sunk their foe.

As the sun set three days later, Salmon’s periscope watch sighted smoke on the horizon while the submarine prowled just below the surface of the South China Sea, about 250 miles south-southeast of Cam Ranh Bay, near 09°00'N, 111°00'E. Salmon stalked the 4,382-ton passenger-cargo vessel Ganges Maru for 55 minutes before the submarine sent her to the bottom with two of three torpedoes fired. On 24 June, Salmon returned to Fremantle and commenced preparations for her next assignment. McKinney later received a Gold Star in lieu of a second award of the Navy Cross for leading Salmon through the “enemy controlled waters of the South China Sea.”

Salmon departed from Fremantle on 21 July 1942 for her fourth war patrol in the South China-Sulu Seas area. Steaming via Lombok Strait, Makassar Strait, the Sibutu Passage, and the Balabac Strait, she hunted between North Borneo and Palawan in the Philippine Islands. During this patrol, Salmon made numerous sightings and reports of shipping movements to sister submarines deployed in the vicinity, but failed to gain favorable positions for successful attacks, and returned to Fremantle on 8 September.

Salmon’s fifth war patrol began on 10 October 1942, and she stalked the area off Corregidor and Subic Bay in the Philippines. On the night of 10 November, she challenged a large sampan moving in the vicinity of Subic Bay, which apparently attempted to slip past during the hours of darkness. The vessel ignored the challenge, and Salmon ordered the sampan to stop and fired shots across her bow. The submarine then closed and lookouts saw that the sampan displayed rising sun emblems on her deckhouse and that crewmen attempted to jettison objects over the side. Salmon’s gunners raked the sampan with .50 caliber machine gun fire, and she stopped. The Americans boarded the sampan, and discovered that most of the Japanese sailors had gone over the side. The boarders removed papers, radio equipment, and other articles, then set the sampan ablaze. As Salmon pulled away, the enemy vessel exploded and sank. Subsequently, while patrolling off the approach to Manila Bay on 17 November, Salmon sighted three vessels and maneuvered to attack, firing torpedoes at each of the ships, succeeding in damaging two and sinking the 5,873-ton converted salvage vessel Oregon Maru about 65 miles northwest of Manila, near 14°16'N, 119°44'E.

Salmon ended her fifth war patrol unsuccessfully when she returned to Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1942, one year to the day when the Japanese attacked. The following day she proceeded to Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif., and arrived on 13 December 1942. Salmon remained at Mare Island until 30 March 1943, undergoing alterations that included the installation of new radar equipment and two 20 millimeter mounts to augment her firepower — alterations necessary for her to operate increasingly closer to the Japanese home islands. She returned to Pearl Harbor on 8 April, and on 29 April sailed on her sixth war patrol via Midway Island. The Navy assigned the submarine a special mission that took her to the coast of Honshū, Japan, at Hachijo Shima, Kantori Saki, and O'Shima. During this mission, she claimed damage to two freighters on 3 June and returned to Midway on 19 June.

During the Battle of Midway [4-7 June 1942], the Japanese had also attacked the Aleutian Islands and occupied the islands of Attu and Kiska. Salmon was therefore dispatched northward to aid in countering the enemy threat there, and the increasingly seasoned boat set out for her seventh war patrol to cut the enemy supply route via Paramushiru-tō [Paramushir] in the Kuril Islands. She departed Midway on 17 July 1943, and on 25 July reached her operating areas, navigating in dense fog that limited visibility to less than 1,000 yards. Salmon nonetheless detected the Japanese vessel Shinko Maru on 9 August and turned to attack, near 46°50'N, 144°40'E. The boat launched four torpedoes from a range of 1,700 yards, but although the ship disappeared from the submarine’s radar scope within a half hour and the crew thus believed that they sank Shinko Maru, the enemy ship escaped.

Salmon redoubled her efforts and on the morning of 10 August 1943 detected the 2,411-ton well-deck fishing vessel Wakanoura Maru off the northern coast of Hokkaido, near 46°55'N, 143°30'E. After closing to a range of 1,000 yards she fired a spread of three torpedoes. One missed ahead, the second hit amidships but was a dud and bounced off, and the third disappeared from view. Salmon therefore shot a fourth torpedo from her bow tubes but Wakanoura Maru’s bridge crew sighted the weapon’s wake and cannily swung the ship sharply and evaded the attack. The change of course gave the submarine a view from her stern forward and the watchstanders observed the Japanese vessel listing heavily and settling aft. Many of her crewmen swung the lifeboats out as if to abandon ship, and Wakanoura Maru turned again and began steering a course for beaching. Salmon attempted to prevent the beaching maneuver and shot another spread of torpedoes, one of which hit the target just at the bow, the explosion carrying a geyser and part of the forecastle high into the air. The ship sank about 25 minutes later, and Salmon triumphantly resumed raiding the cold northern seas. After waiting out a spell of rain and fog, she attacked a ship two days later, but her torpedoes failed and having fired the last of the weapons, returned to Pearl Harbor on 25 August.

Salmon's eighth war patrol saw her set course to return to the Kurils on 27 September 1943. A Japanese convoy comprising freighters Eiho Maru and Nagata Maru, escorted by Submarine Chaser No. 15, stood down the channel from Odomari, Karafuto, on 28 October, bound for Ominato on northern Honshū. Salmon detected the convoy the following night at about 0120, north of Kunashiri Island, near 45°30'N, 146°00'E. The submarine fired three torpedoes for no claimed hits, but two of the weapons apparently struck Nagata Maru and although the torpedoes failed to detonate, they punched one or two holes in Nagata Maru and violent flooding ensued. In retaliation an enemy plane dropped a bomb at Salmon, and the submarine chaser dropped 11 depth-charges, but the boat escaped unscathed. The damaged freighter afterward dropped anchors in the Abashiri Sea and her crew completed temporary repairs, and she thereafter called at Wakkanai, northern Hokkaido, and at Otaru, south-west Hokkaido before arriving at Ominato on 16 November. Salmon returned to Pearl Harbor on 17 November. The hardy submarine carried out her ninth war patrol into the New Year (15 December 1943–25 February 1944), and damaged a Japanese freighter on 22 January.

Salmon departed from Pearl Harbor on her tenth patrol in company with Seadragon on 1 April 1944. The submarines shaped a course for Johnston Island and a special photo reconnaissance mission to support Allied planning to gain control of the Caroline Islands. Salmon reconnoitered the western Carolines, spending about a week at three successive places: Ulithi (15–20 April); Yap (22–26 April); and Woleai (28 April–9 May). Other submarines scouted the Japanese garrisons as well, and Greenling (SS-213) reconnoitered the Marianas, taking photographs, obtaining tidal data, and making soundings. Salmon returned to Pearl Harbor on 21 May with valuable information that Allied planners utilized in last minute changes to their assault plans. Salmon received fuel, lubricating oil, and provisions, and set out (23–30 May) for an overhaul on the west coast. At 0915 on 24 May, she sighted a periscope near 23°15'N, 154°05'W, and sent a sighting report but continued the passage and completed the overhaul at Mare Island Navy Yard (30 May–3 September). The work included replacing her conning tower with an STS conning tower, installing new periscope shears, fitting two 44-foot periscopes, providing ballistic protection for the bridge, and installing double hatches in the after battery, forward engine room, and after torpedo room.

The submarine returned to sea in company with Silversides (SS-236), Cmdr. John S. Coye, Jr., in command, en route to Pearl Harbor (4–12 September), and on 6 September the two boats rendezvoused with Trigger (SS-237), commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Frederick J. Harlfinger. The submarines practiced daily submerged approaches and nightly radar approaches, in addition to training dives, ships drills, and battle surface practices. Cmdr. Harley K. Nauman, Salmon’s commanding officer, reported that “we were well organized when we arrived at Pearl” and recommended the practice for submarines returning from overhauls “when considerable training is urgently needed.” Salmon experienced mechanical and engineering issues, however, and her No. 2 main engine failed because of the attached salt water pump on 7 September, and three days later a flexible coupling failed and knocked her auxiliary engine out of commission, but the submarine completed repairs while moored at Pearl Harbor.

Salmon sailed on her eleventh war patrol as she stood down the channel from Pearl Harbor, her fresh coat of black paint later blending into the gathering dusk, on 24 September 1944. The boat sailed in company with Silversides and Trigger as a coordinated attack group led by Cmdr. Coye. Salmon reached Tanapag Harbor at Saipan and received fuel and lubricating oil while moored alongside submarine tender Fulton (AS-11) on 3 and 4 October. At 1700 on 4 October, Salmon and Silversides stood out of Tanapag on an initial course of 240° at 13 knots. Navy planes patrolled the area and the submarines twice sighted aircraft on 5 October — a Consolidated PB2Y Coronado and then a Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberator. Salmon and Silversides opened the range and formed a scouting line overnight (5--6 October), but heavy seas from the westward repeatedly slowed their progress and compelled them to slow to one to three knots to conserve fuel, and the boats rocked unmercifully in the rolling swells. They also periodically passed through rain squalls, and manned their SJ radar in reduced visibility.

Salmon and Silversides then (10–14 October) reached their operating areas near the Ryūkyū Islands and began patrolling on a generally east-west course along 25°N latitude. The two boats normally ran submerged during the daylight with 10 to 15 feet of their periscopes exposed continuously. They raised their SD antennas on the even hours and listened to the “wolf-pack” frequency, and closed land at night sufficiently to fix their positions with radar ranges and bearings. Lookouts sighted what they believed to be Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 attack plane [Betty] flying an easterly course during the forenoon watch on 11 October, during the afternoon watch a second Betty, and what appeared to be a Mitsubishi A6M Type 0 carrier fighter [Zeke] during the first dog watch. This pattern of enemy aircraft flights continued throughout the deployment, and the following day the Americans spotted a formation of six unidentified planes flying ominously in the distance, though they did not appear to discover the submarines. Allied planes also flew in the area at times, and lookouts sighted what they identified as a flight of three Curtiss SB2C Helldivers during the afternoon watch on 13 October. In addition, the Americans often intercepted Japanese signals at night on their APR electronic warfare gear, and on occasion the enemy appeared to jam the SJ radar. The subs sometimes turned toward the interference to run down the suspected Japanese but usually failed to come to grips with the elusive enemy.

The inaction changed dramatically, however, during the mid watch on 16 October 1944. Just after midnight at 0055, the Japanese jammed Salmon’s SJ radar from the approximate direction of Yonaguni-jima, the westernmost isle of the Ryūkyūs [Yaeyama-shotō]. Salmon challenged the Japanese several times during the night but the enemy coyly disregarded -- or failed to discern -- the challenges. Bridge lookouts sighted a patrol craft bearing 330° (all bearings are given as True) and distance 2,000 yards, near 24°30'N, 123°15'E, as the sun began to rise at 0540, and coached the radar operator, who picked up the boat and tracked her as she turned away and rang up full ahead. Salmon’s starboard lookout reported another patrol craft bearing about 240° at a range of about 1,500 yards just as she submerged. Cmdr. Nauman raised the periscope and sighted this second boat bearing down on the submarine, and swept the horizon but did not spot the first craft. The sonar operator reported a loud blast of air as Salmon dived, and she dropped to 150 feet for three quarters of an hour, just in case. Later that night, she rendezvoused with Trigger and Salmon’s executive officer made a quick trip via rubber boat to the other boat to exchange intelligence information, and the two boats also exchanged the welcome cargo of movies.

Lt. John M. McNeal of Salmon’s ships company endured three attacks of extreme pain that evidently presaged acute gall bladder trouble. The boat consequently surfaced during the second dog watch on 19 October 1944, set a course to the southward, and transmitted a message to Vice Adm. Charles A. Lockwood Jr., Commander Submarine Force, Pacific Fleet, and his headquarters arranged to evacuate the patient. Salmon rendezvoused with Barbel (SS-316) and transferred McNeal by rubber boat at 0753 on 21 October, and then resumed her patrol.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf began when the Japanese launched Operation SHO-1 to disrupt U.S. landings in Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. Enemy shortages of fuel compelled them to disperse their fleet into the Northern, Central, and Southern Forces, that converged separately on Leyte Gulf. American aerial attacks savaged Ozawa’s planes and ships during the Battle of Cape Engaño and he came about. Halibut took part in the battle while on her tenth war patrol with “Roach’s Raiders”, a coordinated attack group also comprising Haddock (SS-231) and Tuna (SS-203). At 0235 on 26 October 1944, Halibut sent what Salmon logged as a “garbled report” that she had detected Japanese “war ships” escorted by three escorts steering a course of 337°. While proceeding to Luzon Strait, the trio of submarines were thus ordered to set up scouting lines to intercept Ozawa’s ships as they retired. The Japanese Central Force, Vice Adm. Kurita Takeo, made a night passage through San Bernardino Strait and at daylight off Samar attacked the Seventh Fleet’s Task Unit (TU) 77.4.3, known as Taffy 3, Rear Adm. Clifton A.F. Sprague in command. Valiant rearguard efforts threw Kurita’s ships into disarray and compelled him to retire despite the Japanese superiority in weight and firepower.

Salmon, Silversides, and Trigger meanwhile hunted for the enemy and at 0920 Trigger reported that she had detected what the crew believed to be two battleships -- possibly two of Kurita’s battleships or cruisers -- and attempted to attack the powerful adversaries by making an “end around” them, near 24°07'N, 125°41'E. Salmon stalked the enemy after receiving the electrifying news, set a course of 51°, and at 1030 sighted a periscope bearing 320°, distance about 1,800 yards, and turned away. The submarines failed to maneuver into position to attack the enemy ships, however, and at 1100 Trigger sent a message that she lost contact with the major warships, which she last plotted steaming 310° at 20 knots. Salmon came about to 320° as Nauman lamented: “It looks like this chase is finished.” Shortly after noon Salmon closed Silversides and the men of the two boats exchanged “dope” (information) about the battle. Salmon, Silversides, and Trigger hunted for the Japanese ships involved in the battle, in addition to merchant vessels, during the succeeding days but without success. Salmon watchstanders experienced some tense moments during the forenoon watch on 28 October, however, when what they believed to be a Mitsubishi G3M3 Type 96 land attack plane flew to the southward, but the Nell continued on its flight without apparently sighting the submarine.

Just after the mid watch at 0401 on 30 October, Salmon patrolled on the surface when her radar detected Takane Maru, a 10,500-ton Japanese merchant tanker zigzagging from 120° and 040° at 12 knots, southwest of Toizaki, Kyushu, near 28°43'N, 131°21'E, bearing 146°, range 20,000 yards. Four enemy antisubmarine patrol vessels guarded the ship, presenting a daunting task to attackers. Salmon went to battle stations and ahead full to get into position to attack, Nauman logging the target as “a whopper.” The submarine edged into a firing solution and dawn found her about 10,000 yards from the target group and 3,000 yards north of the tanker’s intended track. The circumstances did not present an entirely favorable scenario for an attack but the Americans aggressively opted to do so and submerged. The elusive quarry maneuvered out of a good shot, however, so at 0754 Salmon surfaced again and began to chase the ship at full speed. The antagonists repeatedly danced around each other as Takane Maru “radically” rang up course changes and twice disappeared into rain squalls, but Salmon doggedly clung to her prey. In addition, Salmon periodically sent her consorts updates and Trigger followed the missives to close the area and torpedoed Takane Maru near 30°08'N, 132°33'E, at 1620. The tanker circled at 12 knots, while the antisubmarine patrol vessels cruised back and forth at a range of about 1,000 yards from the stricken ship and depth charged Trigger, but she escaped.

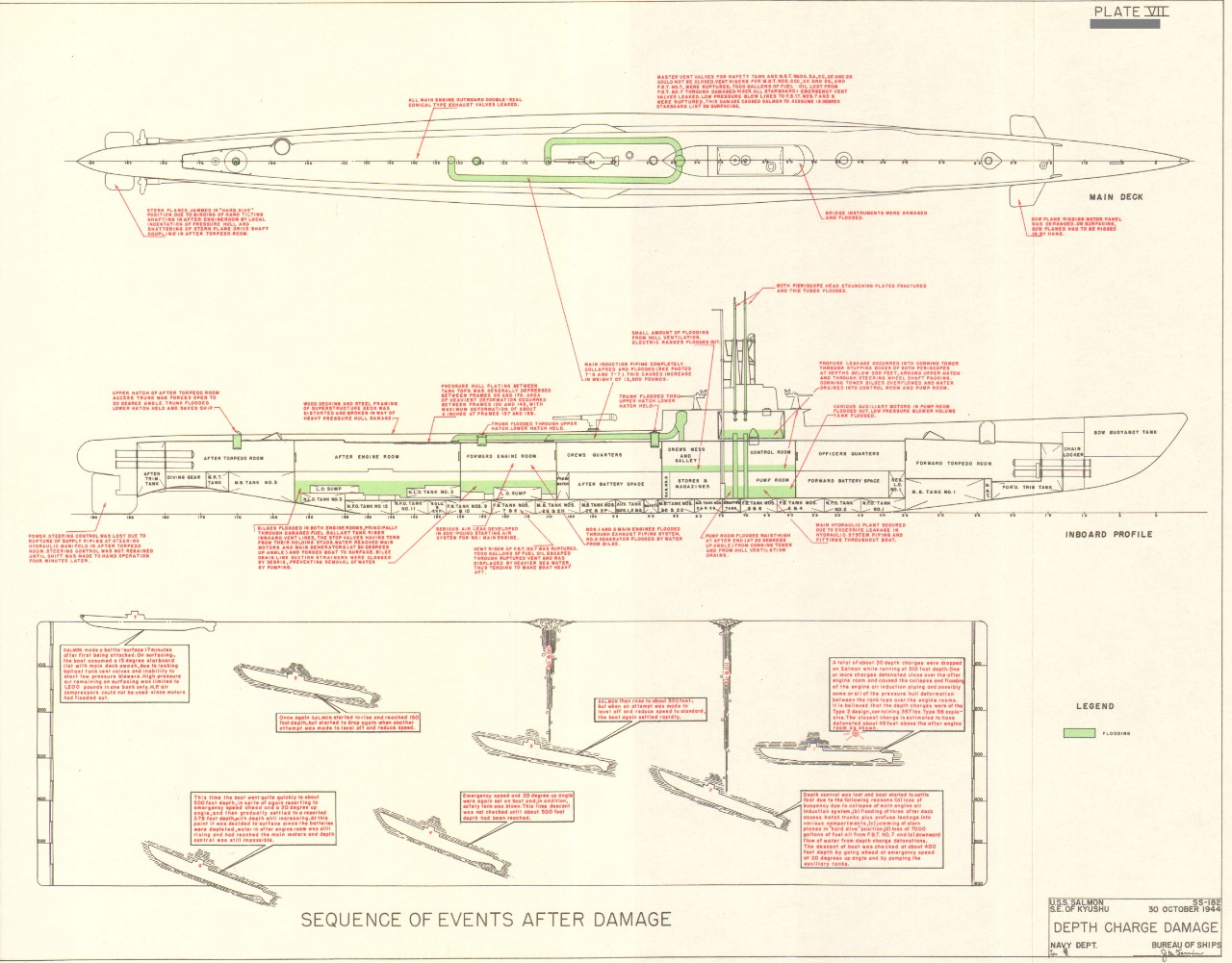

A gentle breeze stirred the air and a full moon began to rise, which would have likely revealed Salmon to alert lookouts, so she submerged and fired four Mk. 18, Mod. 1 torpedoes at a range of 3,300 yards at 2001. The Americans made a less than favorable attack because several of the escorts apparently detected their presence and came about and made speed for the area, so the Americans feared that they would lose their chance to attack later. Nauman watched at least three of the weapons broach the surface, and the sonar operator tracked the fourth to veer about 10° to the left of the others. Salmon swung around to train her stern tubs on the tanker, but the escorts aggressively depth charged the submarine in four patterns of about 30 depth charges that the Americans later reported as “well night perfect” attacks that sounded like a “string of fire-crackers”, beginning at 2013. Salmon leveled off at 300 feet but the depth charges pounded the boat, knocking out her auxiliary power, and sending broken gauges and other gear tearing through the boat as deadly missiles. Salmon dived deep and terrifyingly descended to nearly 578 feet before the crew checked their potentially fatal dive by going ahead emergency and by using a 20° up-angle. Well fittings began leaking badly in the engine rooms, several bad leaks began in the air and hydraulic systems, and the steering and stern planes failed. Salmon rose to about 150 feet but when the submarine attempted to level off and reduce speed she “dropped like a rock”. Her crewmen frantically fought unavailingly for 17 minutes to control the leaking, maintain the boat’s depth level, and get the vital machinery running. Nauman realized their plight and at 2030 reluctantly decided to rise and fight it out on the surface.

Salmon surfaced with her decks awash and a 15° list caused by leaking vents. The lookouts desperately manned their stations and sighted Coast Defense Vessel No. 22 about 7,000 yards away. The enemy seemed wary and held their distance while sniffing out the situation, and gave Salmon's crewmen a few precious minutes to correct the list and to repair some crucial machinery. The depth charge explosions had also blasted the radio and APR antennae from the boat, but her men rigged an emergency wing antenna to transmit. Suddenly at 2100 the Japanese ship turned on her searchlight and illuminated Salmon from a range of about 5,000 yards, and fired a few desultory salvoes that missed. The U.S. submariners manned their guns and the opposing vessels began to close, but Salmon could make no more than 16 knots and the Japanese took advantage of the submarine’s wounds and choose their tactics — Coast Defense Vessel No. 22 ran up on Salmon’s port quarter, sheered out to bring her after gun to bear and fired a few rounds, and then repeated the attack. Salmon held her fire until the enemy ship sheered out and then opened up for about five rounds with the deck gun. The sailors fired some automatic weapons at one point but the range proved too long for effective fire. Enemy shells burst close aboard, often splashing water on the bridge and decks, but the submarine evaded by slowly turning using five to 10° of rudder when the men saw the enemy ship sheered out preparatory to opening fire. Coast Defense Vessel No. 33, one of the other escorts, meanwhile rejoined the fray and added her firepower against the Americans.

At midnight Coast Defense Vessel No. 22 impatiently passed down Salmon’s port beam at a range of about 2,000 yards and fired several rounds that splashed close aboard, as well as a few automatic weapon bursts that tore into the submarine. Salmon slid into a rain squall but when she emerged the Japanese ship headed across the boat’s course and converged on her port bow. The submarine turned on the attacker and passed within 50 yards down the side of Coast Defense Vessel No. 22, training all guns to starboard and raking her with the deck gun and 20 millimeter gunfire, killing and wounding a number of the Japanese sailors topside. The enemy patrol escort briefly and ineffectually returned fire but crossed astern of Salmon and stopped. Salmon then exchanged fire with a second ship, most likely Coast Defense Vessel No. 33, which again seemed to hesitate at some distance while awaiting the other two ships as they approached the scene. Salmon suffered only a few small caliber hits from the enemy vessels, and sent out plain language directions for all other submarines in the vicinity to attack, giving the position of the action. This probably further discouraged the enemy who, likely eavesdropping on the transmissions and fearing other submarines in the area, began milling around pinging on sound gear. The gunfire flashes drew Silversides to the battle, and she attempted to help Salmon by drawing off some of the Japanese. Salmon took advantage of a rain squall and glided within its tenuous shelter at 0045. Crewmen repaired some of the battle damage, which the Navy’s War Damage Report No. 58 evaluated as “one of the most serious to have been survived by any U.S. submarine during World War II”, and she then slipped away slowly at 12 knots on the surface, unable to dive. The enemy jammed radio transmissions and Salmon experienced difficulty raising her consorts, so she hove to and fired a pair of red flares at 2227, and sent her executive officer and some men in a rubber boat across to a nearby submarine she believed to be Silversides, so that they could report to Coye, only to discover Trigger! Silversides signaled them to fire green flares to ensure accurate identification, and Salmon did and they rendezvoused.

Sterlet (SS-392), Lt. Cmdr. Orme C. Robbins in command, sighted Takane Maru southwest of Kyushu, near 30°09'N, 132°45'E, at 0100 the day after the battle — Halloween. The Japanese tanker appeared to be down by the stern and dead in the water, and Robbins did not spot any escorts in the area. He fired six torpedoes by radar bearings, four of which slammed into the ship and she sank without survivors, taking all 66 crewmen and an unknown number of passengers to the bottom. As it turned out, Coast Defense Vessel No. 29 patrolled nearby and briefly pursued Sterlet, but lost contact and the submarine escaped. Salmon subsequently received one-third credit for the tanker.

Following the fierce fighting the Americans did not consider it prudent to linger in the area, and Sterlet, Silversides, and Trigger escorted Salmon to the Marianas —Trigger normally scouting ahead at a range of about 15 miles, and Silversides and Sterlet faithfully shepherding Salmon on her starboard and port beams, respectively. The welcome sight of Liberators and Coronados greeted them as the planes alternatively flew overhead on the second day of their return voyage. Ellet (DD-398) of the Marianas Patrol and Escort Group relieved Trigger at 0840 on 3 November 1944, and the submarine took position astern of the force as Ellet led the submarines into Tanapag, where Salmon moored alongside Fulton at 1950. “The courage, resourcefulness, and determination displayed by them are of the highest order,” Vice Adm. Lockwood summarized, “The efficient performance of duty first saved the submarine from destruction below and then enabled them to outfight and outmaneuver the enemy on the surface even though heavily outnumbered by enemy guns and ships…the entire Submarine Force salutes this stout-hearted vessel and its crew for this last most outstanding performance of duty which terminates a brilliant war career.” Nauman later received the Navy Cross for his “gallantry and intrepidity and distinguished service,” who used his “experience and sound judgment” to fight the battle and bring his submarine back to port.

Salmon subsequently received the Presidential Unit Citation for “extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese surface vessels during a war patrol in restricted waters of the Pacific. Covering her assigned area with relentless determination, the USS Salmon contacted a large hostile tanker, boldly made her approach in defiance of four vigilant escort ships cruising within 1,000 yards of the target and launched her torpedoes to score direct and damaging hits. Damaged by terrific depth charging, Salmon daringly battle-surfaced to effect emergency repairs and fight it out. Firing only when accurate hits were assured, she succeeded in keeping out of effective range of hostile guns and confused the enemy by her evasive tactics until the escort warily closed to ram. In a brilliantly executed surprise attack, she charged her opponent with all available speed and opened fire with every gun aboard to rake the target fore and aft and destroy most of the Japanese topside. Still maintaining her fire, she entered a rain squall to repair her damage before attempting the long run home on the surface. Although crippled and highly vulnerable, Salmon had responded gallantly to the skilled handling of our stout-hearted and indomitable officers and men in turning potential defeat into victory.”

The following month a team of inspectors concluded that Salmon’s damage precluded her return to battle, and recommended that the submarine “be given minimum repairs and assigned ComSubsTrainPac as a battle damage control ship”. The inspectors furthermore recommended that a “skeleton crew” man Salmon while she moored “dockside” — a crew just large enough to enable her to submerge in the event of an enemy attack or emergency, but not large enough to take her to sea. On 10 November, Salmon stood out from Saipan in company with Holland, and sailed via Eniwetok and Pearl Harbor to Naval Drydocks Hunter’s Point at San Francisco, Calif. Workers there repaired the submarine sufficiently to render her seaworthy for a surface run to Portsmouth Navy Yard. They overhauled some of the machinery and painted the hull above the waterline, but mostly left the hull and superstructure intact, except for scrapping the main engine air induction piping and renewing the damaged wooden decking.

Early in the New Year of 1945, the office of Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Navy, directed that Salmon was to serve as an “experimental submarine” under Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, Commander Atlantic Fleet, furthermore authorizing Ingram to make the necessary alterations to prepare the boat for her new role. On 26 January, she departed from San Francisco with Redfish (SS-395), which also steamed en route Portsmouth for repairs, passed through the Panama Canal (6–7 February), and reached Portsmouth on 17 February. After repairs and overhaul at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Salmon was assigned as a training vessel for the Atlantic Fleet. After the war’s end, the Navy counted a great number of submarines, many of them newer, and consequently on 8 September slated her for disposal. Salmon was decommissioned on 24 September 1945, stricken from the Navy list on 11 October 1945, and reported scrapped on 4 April 1946.

Salmon earned nine battle stars for her World War II service in the Asiatic-Pacific area.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Lt. Marvin M. Stephens | 15 March 1938 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Eugene B. McKinney | 2 August 1941 |

Lt. Cmdr. Nicholas J. Nicholas Lt. Cmdr. Harley K. Nauman |

3 February 1943 |

| Lt. Cmdr. William G. Brown | 24 January 1945 |

Mark L. Evans

7 February 2017