Jacob Jones I (Destroyer No. 61)

1916-1917

Jacob Jones was born in 1768 to a well-respected farmer outside the village of Smyrna, Delaware. His parents died at a young age, but young Jacob was able to embark on an education in medicine. Jones obtained an excellent education, first under a local doctor and politician James Sykes, and later at the University of Pennsylvania. After practicing medicine, Jones switched careers to law and Delaware’s Federalist Governor Joshua Clayton appointed him as the clerk of the Delaware Superior Court. He married the daughter of Dr. Sykes who died before Jones entered the Navy.

Early 1799 proved a time of considerable excitement centered around the young U.S. Navy. The nation was engaged in an undeclared naval war with France, and the Federalist circles with whom Jones associated enthusiastically supported the conflict. On 10 April 1799, Jones was appointed midshipman. At 31 years, Jones was exceptionally old for a midshipman most of whom who were in their teens. His motivation for joining the Navy and the means he utilized to secure such an unconventional appointment are unclear. It is likely that his close personal connections, both to early naval officer Capt. Thomas Truxtun and pro-war Federalists served as both means and motivation for his unusual choice. Jones also recruited a body of men from Delaware to serve as sailors. After a short cruise with the frigate United States, the Secretary of the Navy ordered Midshipman Jones to report with his recruits to Philadelphia where he would join the crew of the sloop-of-war Delaware.

During the Quasi-War, Jones served on board United States, Delaware, Ganges, and Constitution. He rose through the ranks of his less mature comrades. While serving in Ganges on 20 July 1800 the ship recaptured the American brig Dispatch which had previously been taken by a French barge. Commanding officer Lt. John Mullowny designated Jones as prize master and delegated him the responsibility to return the vessel to Philadelphia.

Promoted to lieutenant on 27 February 1801, Jones retained his commission under the Naval Peace Establishment Act of March 1801, the most junior ranked commissioned officer to earn that honor. The Secretary of the Navy ordered Jones to report to the frigate Constellation in January 1802. In March the frigate, Capt. Alexander Murray commanding, sailed for the Mediterranean to participate in the conflict against the North African state of Tripoli. While in the Mediterranean, Jones became embroiled in the deadly epidemic of dueling that beset the American squadron there, and served as the second for a U.S. Marine lieutenant who fatally shot a U.S. Marine captain during a duel at Livorno, Italy. Capt. Murray, enraged, arrested Jones as well as others involved in the affair. After being released, Jones was arrested again, that time as a result of a misunderstanding of orders issued by Murray. Lt. Jones was no longer confined when Constellation returned to the United States and Washington sided with him against his commanding officer. In May 1803, the Secretary of the Navy transferred him to the frigate Philadelphia under Capt. William Bainbridge. After a recruiting trip to New York, Philadelphia departed for the Mediterranean on 28 July.

Jones’ brother officers and subordinate bluejackets admired his leadership qualities. Capt. Bainbridge later described him as a “brave and good Officer and a correct man.” Seaman William Ray, a member of Philadelphia’s ship’s company likewise remembered Jones as “a calm, mild, and judicious officer, beloved by all the seamen” – a noteworthy evaluation considering Ray’s criticism of many of Jones’ fellow officers in the narrative he penned about the voyage.

Philadelphia touched at Gibraltar on 24 August 1803 then entered the Mediterranean searching for two rumored Tripolitan vessels. On the night of 26 August, Philadelphia hailed the Moroccan cruiser Mirkoba off the coast of Spain and boarded her. While the boarding party interviewed the captain, they noticed a brig trailing the cruiser. The corsair captain feebly tried to explain that the ship was the U.S. merchant brig Celia, but that Mirkoba had not captured her. After finding an American prisoner on board Mirkoba, however, the Americans determined that the corsair had indeed taken Celia as a prize. Philadelphia in turn captured Mirkoba. After the Moroccan prize crew on board Celia attempted to slip away, Philadelphia spent the following day chasing the vessel and recaptured her.

On 31 October 1803, Philadelphia was enforcing the blockade of Tripoli when she spotted a Tripolitan vessel toward the shore at 9:00 a.m. The frigate engaged in a chase of the vessel while hugging the shore as close as caution would allow. By 11:30 a.m. the American abandoned pursuit and turned out to sea. Suddenly the frigate ran aground on an uncharted shoal and stuck. The officers and crew struggled to free the ship which was stuck at the bow in soft sand. They shifted weight, cast cannon overboard and even chopped down the foremast to lighten the ship all to no avail.

As the crew furiously attempted to dislodge Philadelphia, nine Tripolitan gunboats took advantage and closed on the vessel, firing their cannon ineffectually. The ship settled on the sandbar in such a way that the broadside guns could not engage her assailants. Soon Tripolitan ships positioned themselves to fire completely unopposed at the vulnerable vessel. At 4:30 p.m., Bainbridge gathered his officers and discussed the prospect of surrender. According to him the officers unanimously agreed that the ship was irreversibly stuck and that she should strike her colors. The carpenter attempted to scuttle the vessel. At approximately sundown the Tripolitans took possession of the ship. The Bashaw’s men led the officers and crew into captivity and slavery.

While the Philadelphia bluejackets suffered through hard labor, the officers enjoyed an easier captivity. Headquartered in the former American Consul’s quarters they spent their time reading and learning what they could about the city in which they were imprisoned. Using books donated by the Danish Consul Lt. Jones helped educate the captive midshipmen in a makeshift academy. He also called on his former vocation as a physician to serve as a prison doctor. In June 1805, twenty months after surrender, the Bashaw of Tripoli released the Philadelphia captives as a term of the treaty that ended the conflict.

After being evacuated from Tripoli by the frigate President, Jones served in the frigate Adams (October 1805-January 1806) and the brigantine Etna (May 1806-November 1807). Lieutenant Jones also commanded the brig Argus (1809). During the period he also received the Congressional honor of presenting a gold medal to the venerated Commodore Edward Preble before the old officer’s death. He was promoted to master commandant on 20 April 1810 and on 4 June 1810 assumed command of sloop Wasp.

War with Britain broke out in June 1812 and found Master Commandant Jones still in command of Wasp. Her single action of that war came in October 1812. On the 13th, she cleared the mouth of the Delaware River and, two days later, encountered a heavy gale that carried away her jib boom and washed two crewmen overboard. The following evening, Wasp came upon a squadron of ships and, in spite of the fact that two of their number appeared to be large men-of-war, made for them straight away. She finally caught the enemy convoy the following morning and discovered six merchantmen under the protection of a 22-gun brig Frolic.

At half past eleven in the morning, Wasp and Frolic closed for battle, commencing fire at a distance of 50 to 60 yards. In a short, but sharp, fight, both ships sustained heavy damage to masts and rigging, but Wasp prevailed over her adversary by boarding her. Unfortunately for Master Commandant Jones, his crew, and the gallant little sloop, the British 74-gun ship-of-the-line Poictiers, appeared on the scene, and Frolic’s captor became the final prize of the action. Master Commandant Jones elected to surrender his small ship to the new adversary because he could neither run nor hope to fight such an overwhelming opponent.

Although Wasp was ultimately captured and Master Commandant Jones again became a prisoner, the U.S. celebrated Wasp’s victory over Frolic throughout the United States. When Jones and his crew were exchanged a few weeks later, he was met in New York by other early victorious naval officers of the War of 1812, Capt. Isaac Hull of Constitution and Capt. Stephen Decatur of United States. The State of New York awarded Jones a sword and Congress bestowed on him a gold medal to commemorate the victory.

He also took command of the captured British frigate Macedonian and was promoted to captain in March 1813. Macedonian sailed under a squadron led by Commodore Decatur on board United States. A stronger British squadron soon neutralized the Americans by trapping them in the Thames River with a blockade off of New London, Connecticut. Despite saber rattling from both sides about an arranged and honorable naval duel between the forces, Captain Jones proved unable to put to sea for the remainder of the war.

After the blockade effectively removed Macedonian from the conflict, Captain Jones travelled overland to New York to report on inventor Edward Fulton’s plans for a floating, steam-powered battery. He was supportive of the design but it remained unfinished until after the termination of the conflict. Conceding the blockade to the British, Macedonian was laid up and Captain Jones and his crew travelled to Sackett’s Harbor on Lake Ontario to serve in the squadron under Commodore Isaac Chauncey. There the veteran officer took over the frigate Mohawk and fought some minor skirmishes with the British fleet. Captain Jones and the American fleet sat out the remainder of the war after the British launched the massive 112 gun ship-of-the-line St. Lawrence in October 1814.

Following the termination of the conflict, Captain Jones returned to command Macedonian. The frigate joined Commodore Decatur’s 1815 Mediterranean expedition, the squadron assembled to chastise the forces of the Dey of Algiers who had preyed on American shipping during the War of 1812. After the successful termination of that conflict in 1816 and 1818 respectively he took command of the frigates Guerriere and Constitution, both undergoing extensive repairs at Boston. He returned to the Mediterranean in 1821 as commodore of squadron based there to protect shipping, breaking his broad pennant in Constitution. On return to the United States he served as a member of the Board of Navy Commissioners until 1826. Later that same year, Jones’s broad pennant flew in the frigate Brandywine as he left to command the Pacific Squadron. Relieved on station in 1829, he returned to shore for the final time at the age of 62.

Continuing to serve the navy ashore, he received appointments to a succession of several posts supervising naval institutions at the ports of Baltimore and New York. His final appointment came in 1847 as the Governor of the Naval Asylum at Philadelphia. He died in that post on 3 August 1850 at the age of 82, 51 of those years as an officer in the U.S. Navy, and lies interred in Brandywine Cemetery, Wilmington, Delaware.

I

(Destroyer No. 61: displacement 1,150 (standard); length 315'3", beam 29'10", draft 9'8½" (mean); speed 29.568 knots (trial); complement 99; armament 4 4-inch, 8 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Tucker)

The first Jacob Jones (Destroyer No. 61) was laid down on 3 August 1914 at Camden, N.J. by New York Shipbuilding Corp.; launched on 29 May 1915; sponsored by Mrs. Jerome P. Crittendon [Pauline Cazenove Jones], great-granddaughter of Commodore Jones; and commissioned on 10 February 1916 at the Philadelphia [Pa.] Navy Yard, Lt. Cmdr. William S. Pye in command.

Assigned to Division Eight, Destroyer Flotillas, Atlantic Fleet, Jacob Jones steamed to Newport, R.I. in March 1916 where she conducted trials and exercises to prepare for service. Later that month, Rear Adm. Albert Gleaves, commander of the Torpedo Flotilla, ordered Jacob Jones to Key West, Fla., for shakedown and further trials. From there the ship proceeded to Tampa, Fla., on 22 March for quarantine and fumigation due to a case of smallpox among the crew. The patient was quarantined at Key West and the compartment he slept in was fumigated before the destroyer could return to the port. Jacob Jones continued trials and exercises until May when she underwent repairs on her condensers. After repairs the vessel steamed back to Newport for final trials. On 19 August, however, she was running a final trial when she blew a gasket in the main steam line.

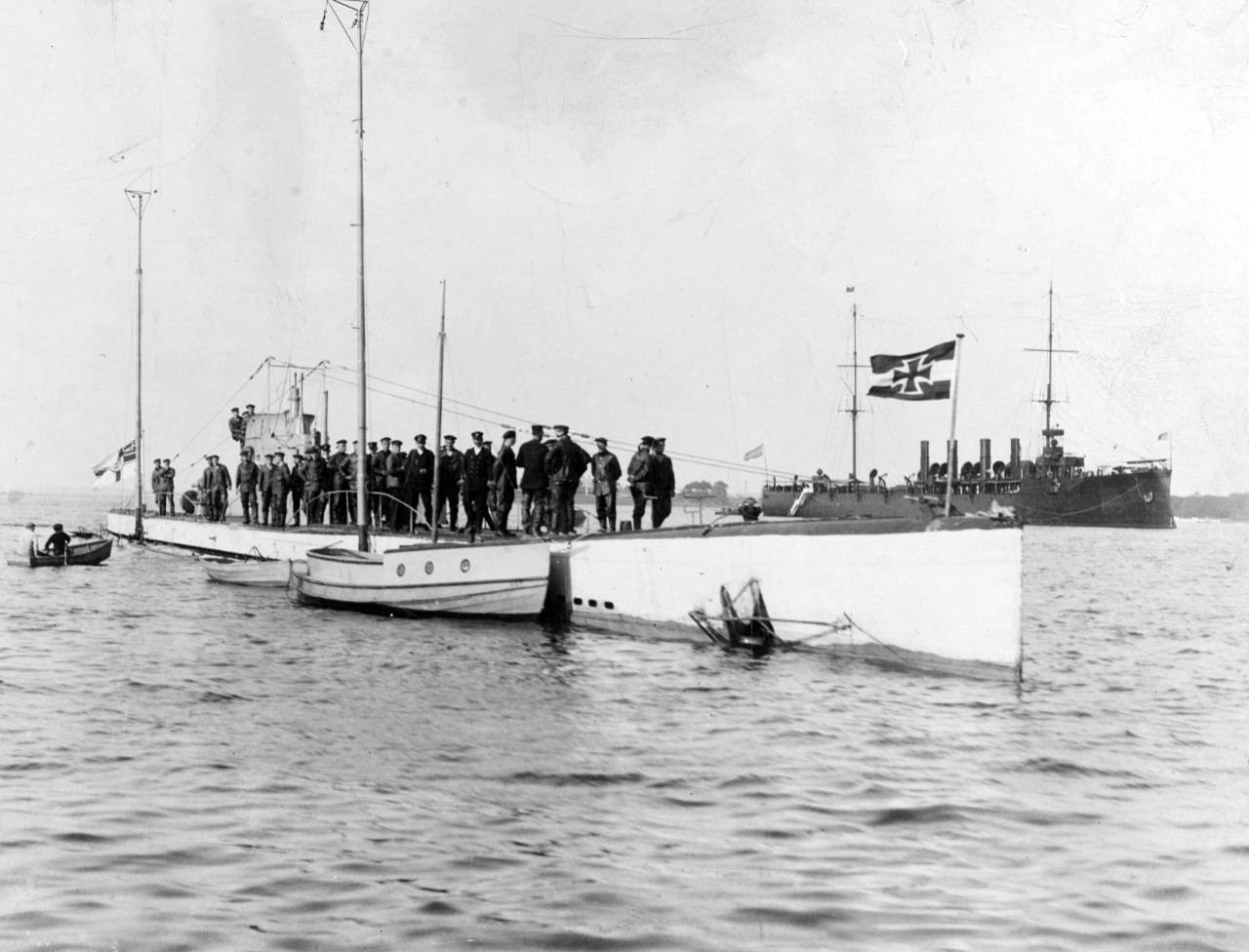

While stationed at Newport, Jacob Jones was present on 7 October 1916 when the German submarine U-53 (Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, commanding) visited the port. In her log, the U.S. destroyer noted the arrival and departure of the unterseeboote that went out to sink five merchant steamers off the coast of Massachusetts, necessitating Jacob Jones being among the 17 destroyers dispatched to rescue survivors.

Jacob Jones again prepared for trials on 29 October 1916 but they were postponed due to machinery derangement. The outcome of the trial, originally rescheduled for 30 October, is unclear but the destroyer was scheduled for additional trials on 8 January 1917 which she failed. The turbine proved to be the reason and work resumed on the ship’s engineering plant on 20 January, the Navy seriously entertaining thoughts of preparing to return the ship to her contractor.

Jacob Jones’ misfortunes continued on 5 February 1917 when she collided with Beale (Destroyer No. 40) while steaming to Philadelphia for repairs to a leaky condenser. On 11 February, Lt. Cmdr. Pye reported that repairs on the destroyer were completed including overhauling the generator and condensers and effecting repairs to no. 4 gun. On 7 March, ready for service at sea, she soon thereafter escorted New Hampshire (Battleship No. 25) from Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to the Virginia capes.

German Submarine U-53 at Newport, Rhode Island, on 7 October 1916. She subsequently attacked Allied shipping off the U.S. East Coast. USS Birmingham (Scout Cruiser # 2) is in the right distance. Note tall radio masts and German Navy flags on the submarine, and the interesting small boat tied up alongside. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command photograph. Catalog #: NH 50090.

Jacob Jones reported to Norfolk, Va., on 23 March 1917 for temporary duty, and much of the Atlantic fleet concentrated in those waters two days later, during a period of increasing international tension. Ultimately, the U.S. declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917, and the destroyer then carried out patrols off the Virginia capes (6-28 April). In late April, Lt. Cmdr. David W. Bagley, her commanding officer, received orders for Jacob Jones to proceed to Boston to fit out for distant service. Jacob Jones underwent eight days of work that ended on 7 May, after which she sailed with the remainder of Division Seven including Cassin (Destroyer No. 43), Ericsson (Destroyer No. 56), Rowan (Destroyer No. 64), Tucker (Destroyer No. 57), and Winslow (Destroyer No. 53), and set course for Queenstown [Cobh], Ireland, as part of the second U.S. destroyer division deployed to European waters.

On 16 May 1917, nine days after leaving Boston, the destroyers were approaching Queenstown at the end of their transatlantic voyage. Amid the watery landscape of wreckage and debris that characterized the wartime Western Approaches to the British Isles the enemy gave the destroyers a taste of the type of war they were about to enter. Ericsson radioed a report of an approaching torpedo, but the “fish” broached and missed the intended target – originally speculated as being Ericsson but later amended to perhaps have been Jacob Jones. The division continued toward their objective, steaming into Queenstown the following day without further incident.

The Americans had little time to rest. On 18 May 1917, the newly arrived destroyers began patrolling the Western Approaches. Jacob Jones dropped her first depth charge in anger on 7 June on a large oil slick. Since surface commanders interpreted such slicks as potentially emanating from a submerged submarine, the destroyer dropped a depth charge at the perceived origin of the oil. The crew did not observe any results. The destroyer repeated this attack on another slick on 28 June and again did not observe any results.

On 8 July 1917, Jacob Jones was on patrol escorting a British steamer at 6:38 p.m. when lookouts sighted a large explosion on the horizon, followed by an S.O.S over the radio. The destroyer worked up to full speed and closed on the scene. Perkins (Destroyer No. 26) followed suit. The two destroyers arrived on the scene in time to witness the British steamer Valetta settling below the waves by the stern having been torpedoed by the German submarine U-87 (Kapitänleutnant Rudolf Schneider). Perkins broke off to search for the attacker while Jacob Jones rescued the crew consisting of 44. The vessel sunk at 8:40 p.m. and the two warships broke off the search to assist the British steamer Cuthbert after she radioed for assistance while being chased by another submarine. They searched for the distressed vessel until she reported escaping from her pursuer at 10:15 p.m.

Jacob Jones picked up an S.O.S. from the British steamer Abinsi at 4:56 p.m. on 15 July 1917 that the merchantman was being stalked by an enemy submarine. Jacob Jones closed on the vessel throughout the afternoon watch, reaching her three hours later. Lt. Cmdr. Bagley ordered his officer of the deck to bring the warship within hailing distance, and although he described the approach as well made, the ships closed and touched, destroying Jacob Jones’ whaleboat. The warship’s commander contended that the steamer was responsible for the collision but in the subsequent inquiry, Capt. Nathan C. Twining, Vice Adm. William S. Sims’ Chief of Staff, disagreed and claimed that Jacob Jones tried to pull abreast of Abinsi when she should only have attempted to pull even at the quarter. Ultimately, Vice Adm. Sims attributed fault to neither vessel.

On 20 July 1917, Jacob Jones spent the morning destroying a derelict vessel and using a floating spar for target practice. At 1:18 p.m., she spotted a submarine six miles away and closed, but the boat submerged before the destroyer arrived, and the latter dropped two depth charges on an oil slick without any observable results.

The following day [21 July 1917] Jacob Jones was escorting the British steamer Dafila and the U.S. steamer Dayton through the western approaches in a moderate fog. Lookouts spotted a periscope 500 yards away through the mist three points abaft port beam between the destroyer and Dafila. A few seconds later, an explosion lit up the steamer’s starboard side amidships as U-45 (Kapitänleutnant Erich Sittenfeld) torpedoed her. Jacob Jones turned to pursue the U-boat but could not train her guns on her before she submerged two minutes later. While the destroyer was still swinging to the right a torpedo wake passed 25 yards under her stern. Jacob Jones attempted to take the fight to the enemy but after thirty minutes proved unable to locate her adversary. At 6:10 p.m., Dafila, bound for Liverpool with a cargo or onions and iron ore, sank and thirty minutes later Jacob Jones slowed to rescue the merchantman’s 25 survivors. While the destroyer lay dead in the water retrieving the survivors at the port gangway, lookouts reported a periscope 200 yards on the starboard quarter. The destroyer’s 4-inch guns immediately responded to the sighting as she gained headway, rushing the remaining survivors up on deck. Crewmembers reported another near torpedo miss 25 yards astern as the destroyer rang down 19 knots and conducted a thorough search for her persistent adversary. She continued searching throughout the last dog watch and into the first watch until Dayton cleared the area. Jacob Jones transferred the survivors on the following day to a British ship at the entry of Bantry Bay, Ireland.

At 10:30 p.m. on 5 September 1917, Jacob Jones located a submarine three points on the port bow 1,500 yards away, and took up pursuit, opening fire from mount 1. The gun misfired and the U-boat submerged as the destroyer closed within 400 yards. The U.S. ship reached the location of the submergence and clearly witnessed a wake, thought to be the submarine’s, crossing her keel just abaft of the bridge at a steep angle, and dropped a depth charge when the enemy boat was believed to be under the stern. Crewmembers claimed that the explosion of the weapon brought oil to the surface and some even claimed to see a body in the water. Another hour of searching did not turn up the alleged body or locate the submarine or its wreckage.

On 19 October 1917, Jacob Jones was escorting a convoy led by the British armed merchant cruiser Orama. Ten minutes before the first dog watch, the escort leader Conyngham (Destroyer No. 58) was exchanging signals with Orama attempting to convince the convoy to change course due to reports of enemy submarines ahead. While engaged in the exchange, the British vessel was struck by a torpedo fired from U-62 (Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashagen) within the confines of the convoy. While other vessels searched for the attacker, Jacob Jones received orders from the escort commander to help evacuate the crew from Orama. The destroyer’s quick response to those orders helped save 305 survivors (there were five casualties), whom she disembarked at Milford Haven the following day.

While escorting a convoy with U.S. and British destroyers on 17 November 1917, Jacob Jones was present for the destruction of German submarine U-58 (Kapitänleutnant Gustav Amberger). Fanning (Destroyer No. 37) and Nicholson (Destroyer No. 52) received credit for the victory when Fanning forced the submarine to surface. After Fanning left the convoy to take the prisoners to port, Jacob Jones took her place in the convoy. The incident was the war’s only confirmed U.S. destroyer victory over a German submarine unassisted by British forces.

On 6 December 1917, Jacob Jones handed off a convoy off Brest, France, and set course for Queenstown, holding target practice that afternoon. The gunfire attracted U-53 (Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose) -- the same ship and captain that had visited Newport while Jacob Jones was tied up there one year before. The U-boat stalked the destroyer unseen, closing from 2-3 miles to 1,000 meters, and fired a torpedo from her bow tubes.

At 4:21 p.m., the cry of “Torpedo!” pierced the cold and drew attention to a perfectly straight wake speeding toward amidships off of the starboard beam. Lt. (j.g.) Stanton F. Kalk, the officer-of-the-deck, ordered the rudder put hard left, while Lt. Cmdr. Bagley rang up emergency speed as the ship began to swing. The crew sprang into action as the torpedo closed, broaching then plunging beneath the waves approximately sixty feet away from the starboard side.

The torpedo struck Jacob Jones three feet below the waterline in the fuel oil tank between the auxiliary room and the after crew space. Many men died in the blast and compartments immediately took on frigid water from the winter sea. On impact, the ship began to settle aft. F1c David R. Carter struggled against the intense pressure of the encroaching sea to seal the watertight door between the auxiliary compartment and the engine room but the task proved impossible. Lt. Cmdr. Bagley attempted to send off an S.O.S. to friendly forces but the antenna had been carried away by the explosion and the sea.

Topside, amidst the frantic and determined activity, officers and men raced the rising water to cut loose lifebelts, boats, life rafts -- anything that would float. Lt. John K. Richards, Jr., the gunnery officer, attempted to reach the depth charges to set them on “safe” but could not reach them due to the damaged and twisted state of the stern. CEM Lawrence J. Kelly distinguished himself by staying with the rapidly sinking vessel to free as much life preserving equipment as possible. He was credited with saving several lives. Lt. Cmdr. Bagley ran along the deck and ordered the crew overboard. Lt. Norman Scott, the executive officer, gave orders to shut off steam and release lifeboats and lifesaving equipment. Sea2c Philip J. Burger struggled to release the motor sailer from the ship, refusing to give up until the suction from the sinking vessel drew him under water. He was able to resurface and swim to the safety of the boats. In a final attempt to draw the attention of any friendly vessels in the area, the no.4 gun fired two shots over the open water. At 4:29 p.m., only eight minutes after being torpedoed, the bow of the destroyer swung upwards twisting 180 degrees in the process, pausing nearly upright before Jacob Jones plunged, stern-first.

The survivors’ ordeal, however, continued after escaping the vessel. The process of sinking released several depth charges that exploded, killing several men in the water and injuring more. The North Atlantic winter left the survivors, many lightly clad due to their rush to escape the ship, to struggle in the frigid ocean. Survivors pulled their comrades on board the surviving lifeboats, one motor dory, a few rafts, and a leaky wherry.

On board the rafts and in the boats acts of self-sacrifice abounded. BM1c Charles Charlesworth provided his shipmates with some of his clothing in attempts to keep them warm and alive. CPhM Ernest H. Pennington described a few years after the war how a shipmate noticed that the lightly clad Pennington was on the verge of death. The sailor removed his own heavy coat and succeeded in saving his shipmate’s life. Lt. (j.g.) Kalk, despite his weakened state, swam from one raft to another in the icy sea to equalize the weight on the rafts and help fellow sailors until he succumbed to exposure during the night. His shipmates considered him “game to the last.”

vchAs the Americans struggled to survive the ordeal and save their shipmates, U-53 surfaced and brought Sea2c Albert DeMello and SC2c John F. Murphy on board before she submerged. DeMello, taken below to the cramped confines of the German boat, noticed the wireless operator transmitting a message, and turned to Kapitänleutnant Rose and inquired: “Notifying your sister ship of your victory?” Rose responded: “No, I am sending an S.O.S to Land’s End [England] for the remainder of your shipmates as I have no more room for more of you aboard [sic].”

Indeed, Rose allegedly transmitted an S.O.S to the British station and provided the location of the survivors, a gesture praised in post-war accounts as an act of chivalry uncommon in modern war. The German submariner, however, may have also had less noble motives, as he wrote in U-53’s war diary that he called for help partly “in the hope it might increase the breach which I was given to understand from the statement of one of the prisoners existed between American and British Naval Personnel.”

If Kapitänleutnant Rose intended to drive a wedge between English-speaking allies, the important role of British ships in the recovery effort foiled any possibility of success. Three and a half hours after the sinking, the British steamer Catalina recovered seven of Jacob Jones’ survivors and radioed for help, Catalina’s transmission, not U-53’s, alerting the allied command to the loss. The British sloop HMS Camellia (K.31) recovered the main group of survivors on three boats at 8:30 a.m. the following day.

Lt. Cmdr. Bagley earlier led a surviving motor dory toward the Scilly Islands to seek help and a British patrol boat picked that group up at 1:00 p.m. on 7 December. The leaky wherry containing five men also set out for the Scilly Islands but was never seen again and likely sank. Of the 110 souls on board the vessel, 62 died in the torpedoing and its aftermath. For actions taken during the sinking, the Navy awarded Lt. Cmdr. Bagley and Lt. (j.g.) Kalk the Distinguished Service Medal, then the highest medal awarded by the Department. The Navy later also named two destroyers in honor of Lt.(j.g.) Kalk. CEM Laurence J. Kelley, CBM Harry Gibson, QM3 Howard Chase and WT Edward Meier each received the Navy Cross. An investigation into the loss concluded that the officers and crew of the Jacob Jones had conducted themselves in accordance with the best traditions of the service.

Jacob Jones was stricken from the Navy Register on 17 December 1917.

S. Matthew Cheser

Updated, Robert J. Cressman

29 February 2024