Douglas L. Howard (DE-138)

1943–1946

Douglas Legate Howard -- born on 11 February 1885 in Annapolis, Md., the eldest son of Lt. (later Adm.) and Mrs. Thomas B. [Anne J.] Howard -- he entered the United States Naval Academy in 1902, where he played on the football team through the 1902, 1903, and 1904 seasons, becoming the team’s captain in 1905. Howard graduated from the Naval Academy in 1906. He later married Ruth Bowyer, a union that produced two children, John M. B. and Anne C.

Howard became the assistant coach of the Naval Academy’s football team (1906–1911), being ordered to the institute for that purpose on temporary detached duty from his regular tours of duty with the fleet. He became the Naval Academy’s head coach (1912–1914), leading the team to a total record of 25–7–4. His leadership inspired his students, and their class of 1914 dedicated the Naval Academy’s annual, The Lucky Bag, to Howard.

He received the Navy Cross for his distinguished service as the commanding officer of Drayton (Destroyer No. 23), Rowan (Destroyer No. 64), and Bell (Destroyer No. 95) during World War I, “vigorously and unremittingly” escorting Allied convoys through waters “infested” with German U-boats and mines. He was detached from Bell in April 1919 and ordered to duty as the Director of Athletics at the Naval Academy (1920–1922) until January 1923, when he was ordered to battleship Texas (BB-35) as her navigation officer. In July of that year, he was transferred to Seattle (CA-11) as her executive officer, and then (1925–June 1928) returned to duty at the Naval Academy. Howard followed that assignment by commanding Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 27 of the Scouting Fleet until April 1930, and later took command of DesDiv 33. He completed instruction at the Naval War College at Newport, R.I. (July 1930–June 1931), and the following year attended the Army War College at Washington, D.C.

Capt. Howard served in the Office of Naval Intelligence from July 1932 until he retired in 1933. He served as the Dean of St. John’s College at Annapolis, and worked as the president of the Annapolis Banking and Trust Company. Howard died suddenly at Annapolis on 14 December 1936. Cmdr. William N. Thomas, Chaplain Corps, officiated at Howard’s funeral service at the Naval Academy Chapel and his interment in the Naval Academy Cemetery.

(DE-138: displacement 1,200; length 306'; beam 36'7"; draft 8'7"; speed 21 knots; complement 186; armament 3 3-inch, 3 21-inch torpedo tubes, 8 depth charge projectors, 1 depth charge (hedgehog type), 2 depth charge tracks; class Edsall)

Douglas L. Howard (DE-138) was laid down on 8 December 1942 at Orange, Tex., by the Consolidated Steel Corp., Ltd.; launched on 24 January 1943; sponsored by Mrs. D. I. Thomas, daughter of Capt. Howard; and commissioned on 29 July 1943, Lt. Cmdr. Gordon D. Kissam, USNR, in command.

After acceptance trials, the ship completed outfitting at Galveston, Texas, and New Orleans, La., and then (15–20 August 1943) carried out her shakedown cruise off Bermuda. Following her shakedown, she completed repairs and upkeep at Charleston [S.C.] Navy Yard, and reported to Cmdr. John H. Forshew, USNR, Commander Escort Division 9, who broke his broad pennant in Douglas L. Howard, at Norfolk, Va. (27–28 September).

Douglas L. Howard began her first wartime deployment when she sailed with Task Group (TG) 65 as part of TG 21.15, escorting convoy UGS-20 from Hampton Roads, Va., to Casablanca, Morocco, and various ports in the Mediterranean (4–22 October 1943). She completed the voyage without engaging the enemy, and after an availability at the New York [N.Y.] Navy Yard (28 October–16 November), and a short period of training in Casco Bay, Maine, she returned to TG 65 on 3 December. She helped escort UGS-26 to Casablanca (4–20 December), and returned with GUS-25 on 28 December 1943, making both voyages without incident.

The ship accomplished antisubmarine training off Block Island early in the New Year (17–30 January 1944), and joined the escort of her third convoy when she stood out to sea with TG 65 and shepherded UGS-32 from Hampton Roads to Casablanca (3–19 February). She returned with convoy GUS-31 to New York (25 February–19 March). In company with the other ships of the division, Douglas L. Howard then joined TG 21.16, a hunter-killer group operating with escort aircraft carrier Core (CVE-13).

The group sailed from Hampton Roads and hunted German U-boats in the North and Central Atlantic (3 April–30 May 1944), though Douglas L. Howard briefly detached from the patrols to refuel and repair her bilge keel at Fayal in the Azores on 17 and 18 April. The task group was then disbanded, and the escort ships completed an availability at New York, during which a Combat Information Center (CIC) and High Frequency Direction Finder equipment, known to sailors as “Huff Duff,” was installed in Douglas L. Howard. The ship then made a similar antisubmarine patrol with TG 22.6, a group formed around Wake Island (CVE-65), reporting on 11 June at Norfolk and crossing the Atlantic to Casablanca shortly thereafter (15 June–24 July). Douglas L. Howard watchstanders sighted what they believed to be enemy submarine’s periscope on 12 July, but the ship fired depth charges without apparent results. The group returned to New York (24 July–29 August).

On 2 August 1944, Allied intelligence information, most likely from intercepted and decrypted German signal traffic, indicated that a U-boat might be operating near the area of 48°N, 33°W. Analysts surmised that the German submarine could be deployed as a weather monitoring boat to direct other submarines around heavy seas. A second U-boat appeared to be steaming westerly courses in the area of 46°N, 30°30'W. The Navy thus directed the task group, while homeward bound, to come about and make for the first suspected position. During the forenoon watch, the ships steered a base course of 310°, speed 15 knots, zigzagging in accordance with Plan 6 (USF 10A). The escorts steamed clockwise in a protective screen around Wake Island: Farquhar (DE-139); Fiske (DE-143) (Lt. Cmdr. John A. Comly, USNR, in command); J.R.Y. Blakeley (DE-140); and Douglas L. Howard. Hill (DE-141), encountering problems with her sonar gear, proceeded in station. Cmdr. John H. Forshew, Commander Escort Division 9, again broke his broad pennant in Douglas L. Howard.

At 1157 a Douglas L. Howard lookout sighted a white puff of smoke, such as diesel motors give off when subjected to a sudden load, and an undistinguishable object bearing 270°T, range nine miles, approximately 800 miles east of Cape Race, Newfoundland, near 47°11'N, 33°29'W. The ship’s SL radar then detected a contact at that position, but the radar team only gained several sweeps before the pip disappeared, and crewmen maintained visual contact for approximately three minutes until their quarry, German submarine U-804 (Oberleutnant zur See Herbert Meyer in command) dived. Forshew ordered the ship to come about and investigate the contact, and directed Fiske to accompany her. Douglas L. Howard came to course 275° and 21 knots, and Forshew directed Fiske to steer 285° and her best possible speed. The ship’s No. 1 main engine developed trouble in its servo-motor, however, and she could barely make 20 knots. A slight interval of nearly 4,000 yards thus developed between the two ships, placing Douglas L. Howard a few degrees forward of Fiske’s beam. The two ships began searching for the submerged enemy boat with their sonar. Both escorts made contact almost immediately at 1232, and Fiske reported a weak sonar echo bearing 183° at 2,000 yards and turned in for an attack approach. Comly prepared to drop depth charges or fire 7.2-inch hedgehogs, and as he closed the range to about 1,075 yards did not believe that the Germans utilized any ruses, such as Bold (Kobold) or Pillenwerfer sonar decoy pellets.

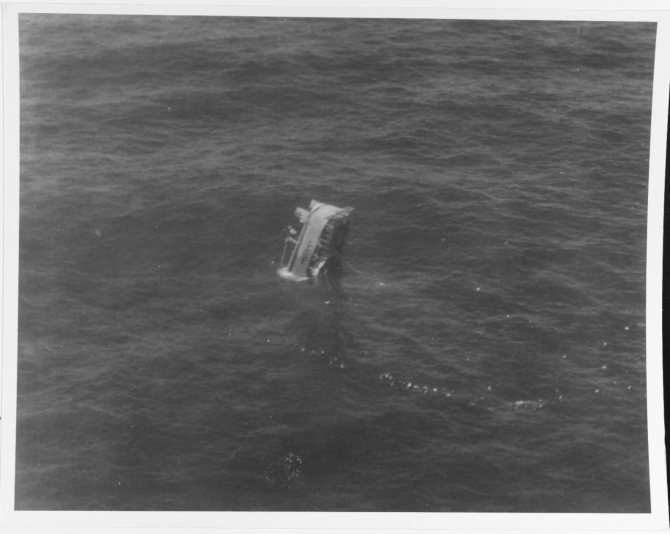

Meyer fired three torpedoes, however, two of which punched into Fiske’s starboard side amidships at 1235. No one saw torpedo wakes and the sonar failed to detect propeller cavitation. The explosion rocked the ship, lifting her amidships but thrusting her downward by both the bow and stern. The attack broke the ship’s back and she quickly settled to be awash amidships with reduced free board fore and aft, and a port list of about 20 degrees, slowing righting to about 15 degrees. The torpedo hits blew compartments B-3 and B-4 out to port and starboard, flooding them rapidly, buckled and then tore loose the starboard main deck and tore the port side main deck, crumpled 20 millimeter platforms 5 6, 7, and 8, and blew off some hatches in the stern section. Sailors manning stations aft floated free of the deck, and Fiske lost all communications and power. Men fought to keep the ship afloat and rigged emergency sound powered telephones, set depth charge safeties, and secured the hedgehogs. Within five minutes a muffled explosion occurred forward in the vicinity of the paint locker, causing a blinding flash and dense smoke that prevented men from investigating. Fiske broke in two at 1245, and Comly proudly reported that the crew abandoned ship in an “extremely orderly process.”

Douglas L. Howard and J.R.Y. Blakeley each made several hedgehog and depth charge attacks on U-804, and on what Douglas L. Howard’s sonar team believed might be a second submarine lurking nearby, but many of Fiske’s survivors awaited rescue in the water barely 1,000 yards from the German submarine’s last known position. The escort thus exercised caution in ranging her attacks and U-804 escaped. Fiske’s bow section sank at 1342 and Douglas L. Howard sank her stern section with gunfire at 1645. The ship took 33 men with her. Farquhar rescued Comly and the other 179 survivors, 50 of whom were wounded, and took them to Argentia, Newfoundland, for immediate medical attention, clean clothing, and rest, whence to Boston, Mass., for further treatment. Douglas L. Howard came about from the patrol on 15 August and proceeded to Casco Bay for exercises, and then completed sonar repairs at Boston (2–3 September).

Following the yard work Douglas L. Howard joined TG 22.1, formed around Mission Bay (CVE-59), at Hampton Roads and then hunted for German U-boats in the South Atlantic (8 September–26 November 1944). Her original orders called for intensive practice maneuvers with a U.S. submarine off Bermuda, but a severe hurricane compelled the Navy to change the orders and redirect the group to refuel at the Free French port of Dakar, Senegal (20–23 September). Upon returning to sea to search for U-boats west of the Cape Verde Islands, Mission Bay repeatedly launched Eastern FM-2 Wildcats and TBM-1C and -1D Avengers of Composite Squadron (VC) 36 that flew combined searches up to 180 miles from the group. Lt. (j.g.) Theodore W. Gilbert, USNR, led one such flight of planes that encountered a disappearing radar contact followed by suspicious sonobuoy indications, on 26 September. The group steamed toward a rendezvous with Tripoli (CVE-64) and TG 47.7, however, which searched along the estimated track of two U-boats slated to rendezvous for refueling. One of the target U-boats was U-1062, a Milchkühe (‘milk cow’ refueling submarine) bound from Penang, Malaya, with a cargo of valuable petroleum products for the German war effort. Ordered to fuel U-219, outward-bound for the Far East, U-1062 prepared to rendezvous with the smaller boat in the South Atlantic narrows—directly in the path of the Tripoli escort group. Mission Bay and her consorts thus did not make a prolonged search and shaped a course to rendezvous with Tripoli.

While en route to the carrier three ships including Douglas L. Howard detected a radar contact nine miles ahead of the group on 28 September 1944. The pip persisted on radar screens for more than ten minutes, and Douglas L. Howard’s CIC team evaluated the contact as a likely enemy submarine steaming on the surface on a southerly course. The escorts made sound searches and Mission Bay launched planes that dropped sonobuoys throughout the day searching a wide area for the elusive German boat. Lt. (j.g.) William H. Brett, USNR, flew an Avenger that attacked what he believed to be a submerged U-boat at 1735, but the submarine escaped. Mission Bay meanwhile rendezvoused with Tripoli, which launched FM-2s and TBM-1C and -1Ds of VC-6 to continue the battle. Planes from VC-36 relieved those of VC-6 and laid sonobuoy patterns that produced suspicious underwater sounds. The planes directed ships of the screen to the scene shortly after midnight, which searched the area into the next day but failed to establish contact.

During the first and second dog watches on 28 September, T 1, T 3, T 7, and T 11, TBM-1Cs flown by Lt. (j.g.) Joseph W. Steere, Lieutenants Charles W. Smith and William R. Gillespie Jr., USNR, and Lt. (j.g.) Morris Nelson, respectively, launched from Tripoli to search 80 mile sectors from the ship. Lt. (j.g.) Douglas R. Hagood catapulted aloft in F 23, a Wildcat, to fly combat air patrol (CAP) over the ship. Clouds frequently obscured the moon light. At 1942 -- shortly after sunset -- Gillespie detected the surfaced U-219 only 11 miles from the enemy’s estimated track and about 25 miles south of Brett’s attack position, and radioed Tripoli: “I’ve got him, I’ve got him. He’s shooting at me (garbled)…Am going in to make run.” T 7 went in to conduct a low-level rocket attack, but heavy flak shot down the intrepid airman’s plane. Steere flew a return leg of his search back to Tripoli, observed the antiaircraft fire off his port bow, and headed toward the battle. The firing stopped as Steere approached, and he searched vainly for the Germans until he saw heavy and accurate antiaircraft fire rising from under his port wing. He made a full turn to the left, braved the maelstrom of flak and flew another rocket run, firing four pairs of rockets and pulling up barely 500 feet above the U-boat. The fighting also drew Hagood and he strafed the twisting and turning U-boat, which struggled desperately to dodge the harassing attacks by the American planes. The Germans’ tracer glare prevented the Wildcat pilot from assessing the damage from his machine guns, but he believed that his .50 caliber bullets “thoroughly covered” the conning tower. Steere meanwhile swung around and made a second run, dropping two depth charges, and then circled for a third pass, dropping a mine and a sonobuoy into the still visible swirl in the submarine’s wake. The airmen persevered in their hunt and at times underwater sounds from the sonobuoy and detected a radar pip, but U-219 emerged from the affray unscathed. U-1062 did not enjoy similar good fortune.

The two task groups renewed their joint operations the following evening and at midnight, VC-36’s Lt. (j.g.) Robert A. Straub, USNR, detected a disappearing radar contact and dropped sonobuoys, which indicated a likely enemy submarine. His attack marked the beginning of a long round-the-clock vigil by the ships and prowling, radar-equipped Avengers extending into 6 October. Approximately four hours later, Lt. E.P.W. Schwan, USNR, flew another Avenger and had two disappearing radar contacts about eight miles southwest. He made a searchlight run and did not spot a surfaced U-boat or periscope, but Schwan determinedly laid sonobuoys and regained contact. An Avenger flown by Lt. James N. Dau, USNR, attacked at 0650 on 30 September. Dau tracked U-1062 on sonobuoys more than ten miles farther to the southwest and together with planes flown by Lt. Cmdr. Francis M. Welch, along with Lt. Joseph R. Daly, Brett, Gilbert, Ens. E.G. Booth (all USNR), and carried out a series of attacks against the U-boat. During those runs the planes also called three ships to the area, that entered the area of the latest sonobuoy pattern and gained contact at 1530, only to quickly lose the submarine.

Douglas L. Howard and Fessenden (DE-142) searched about six miles south and one mile west of the original contact position, in the mid-Atlantic near 11°36'N, 34°44'W, when Fessenden reported a good sound contact at 1630. A minute later Fessenden fired four 7.2 projector charges and reported an explosion, the sound waves echoing off Douglas L. Howard, followed by the grim sound of a boat breaking up. Debris and what the ship’s historian reported as “immense quantities of oil” bubbled to the surface and covered the water for several days afterward, and Fessenden correctly evaluated her attack as a probable kill. Planes resolutely continued to search for proof of U-1062’s loss until 6 October, by which point they logged 676 hours of flying. Aircrew recorded 11 spools of wire recordings during the battle and subsequently brought them back to Norfolk, where evaluators exhaustively studied the sounds and incorporated excerpts into sonobuoy training records.

In the meantime, T 2, one of Tripoli's Avengers flown by Lt. Charles A. Shortle Jr., USNR, dropped depth bombs on U-219 as she fled on 2 October. Keen-eared American sonar-men felt that they had definitely “killed” the submersible, but postwar investigations showed that U-219 had escaped to Batavia [Jakarta], Java, Netherlands East Indies [Indonesia]. Douglas L. Howard continued to screen Mission Bay and while steaming southerly courses en route to Bahia, Brazil, she crossed the equator on 12 October 1944. When fuel supplies ran low, Tripoli came about and made port at Recife on 12 October. She conducted one further search of the narrows from 26 October to 12 November before heading for a much-needed overhaul at Norfolk. Mission Bay and her group visited Bahia (15–19 October), and the planes and ships unsuccessfully carried out antisubmarine patrols in a southeasterly direction. The ships visited Cape Town, South Africa (30 October–2 November), and then came about for home, stopping briefly at Recife, Brazil (13–15 November), and returning to Norfolk and New York. Douglas L. Howard trained in antisubmarine and firing exercises off Block Island and New London (12–17 December 1944), and then rejoined Mission Bay.

The ships steamed southward for refresher training (RefTra) and Douglas L. Howard repaired her sound gear at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, which lasted until 16 January 1945, when the ship faithfully escorted Mission Bay while the carrier qualified aviators in carrier operations off Mayport, Fla. (22 January–7 February). The ship then completed additional training off Guantánamo Bay, but immediately upon arrival was redirected to the Central Atlantic. She steamed eastward independently and rendezvoused with Savannah (CL-42), and then escorted the light cruiser westward and rejoined the task group on 25 February. Two days later Douglas L. Howard reached the east coast, steaming via Bermuda for an availability at New York, where she arrived on 8 March. Allied intelligence information indicated that some long range German U-boats might be crossing the Atlantic to attack ships off the east coast, and Douglas L. Howard thus took part with TG 22.1 from Norfolk in an extended 120 mile barrier patrol with TGs 22.13 and 22.5 in the North Atlantic north and south of 48°30ˈN, 30°W (27 March–14 May). She operated in different areas when ships detected what they believed to be U-boats on two separate occasions, twice refueled at Argentia, and steamed at sea when she received word of the German surrender on 8 May 1945. Mission Bay subsequently made for Norfolk and Douglas L. Howard with the other escorts returned to New York for ten days of rest and recreation.

On 25 May 1945 she reported to Submarine Squadron 1 at New London, Conn., and on the last day of the month rejoined Mission Bay and served as her plane guard while the carrier trained pilots off Narragansett Bay, R.I., Block Island, and southwest of Nantucket Island, Mass. The ship completed an availability at the Boston Navy Yard in preparation for her transfer to the Pacific (9–30 June). Douglas L. Howard sailed from Boston on 30 June, accomplished RefTra off Guantánamo Bay (5–18 July), passed through the Panama Canal on 21 July, touched briefly at San Diego, Calif., on the first of the month, and reached Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, on 8 August. The ship completed antisubmarine and firing and calibration exercises with TU 10.15.4 in Hawaiian waters.

The Japanese surrendered but their many garrisons deployed across the Pacific concerned Allied planners because of the possibility that they might continue resistance, so on 3 September 1945 the ship reported to Eniwetok for patrol and local escort duty, remaining anchored there until 25 September. Douglas L. Howard assisted in the occupation of Lele harbor on the island of Kusaie in the Carolines, and the disposition of the military equipment the Japanese garrison surrendered (25 September–16 November). She rendezvoused with Soley (DD-707) and Ricketts (DE-254) at Lele, and Ricketts, requiring fuel and supplies, departed when Douglas L. Howard arrived, but returned on 1 October. In company with these ships and with small coastal transport APc-95, Douglas L. Howard assisted with disarming the Japanese troops, and aided Allied humanitarian relief efforts to the native islanders. Soley and Ricketts departed on 13 October, and Japanese hospital ship Hikawa Maru arrived off Kusaie on 4 November to evacuate the Japanese from the island, sailing with them embarked for Japanese waters the following day. Farquhar relieved Douglas L. Howard on 15 November, and she reached Eniwetok in the Marshalls the next day. The escort ship remained there until 21 November and then shifted to Kwajalein, where she served on occupation duty until 6 January 1946. Douglas L. Howard then stood out of Kwajalein for the United States, calling at San Diego (23–30 January), and continuing to New York, reaching that port on 15 February. On 13 March she arrived at Green Cove Springs, Fla., where she was placed out of commission in reserve on 17 June 1946.

Stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 1 October 1972, ex-Douglas L. Howard was sold on 1 May 1974. Civilian tugs Bulldozer and Bubba Rico of Emerald Marine Service of Orange, Texas, took the veteran of combat with German U-boats in tow at 0840 on 7 June 1974, and set course for the facilities of Norman Weinrib Scientific Marine Salvage Co., Marathon, Fla., where she would be broken up.

Commanding Officers Date Assumed Command

Lt. Cmdr. Gordon D. Kissam, USNR 29 July 1943

Cmdr. William F. Stokey, USNR November 1943

Lt. John T. Pratt Jr., USNR 29 August 1944

Lt. Maurice B. Baker Jr., USNR 5 August 1945

Mark L. Evans

18 May 2016