Capodanno (DE-1093)

1973–1995

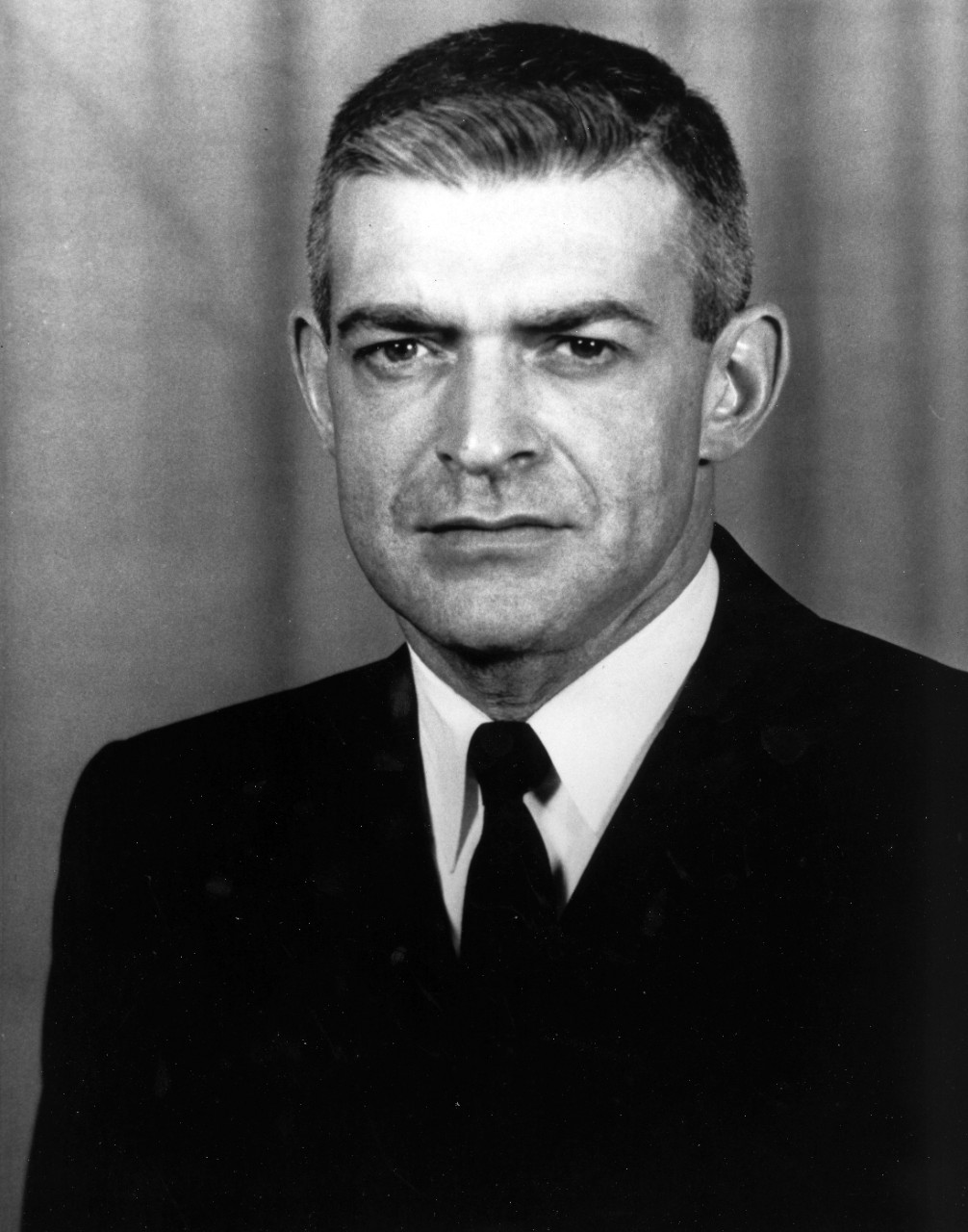

Lt. Vincent Robert Capodanno — born on 13 February 1929 in Richmond County, N.Y. — was the youngest of ten children, and was named for his father, Vincent Capodanno, Sr., an immigrant from Gaeta, Italy. Although raised in a traditional Catholic household on Staten Island, N.Y., there were no early indications that young “Vin” aspired to be a priest, let alone one who ministered to those on the frontlines of a major conflict. Indeed, he did not even confide in anyone that he felt called to the priesthood until he was 20 years old and already working as an underwriting clerk at an insurance firm while attending night classes at Fordham University. Finally acting upon this desire, Capodanno applied to join the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America, better known as the “Maryknolls.” Founded just over thirty years earlier, the Society was the first Catholic missionary organization of its kind in the U.S., training its members to live and preach their faith in the far-flung corners of the world. Upon his acceptance into the Maryknolls in 1949, Capodanno spent the next decade of his life undergoing rigorous academic and theological instruction, receiving his B.A. in Philosophy from Maryknoll College in Glen Ellyn, Ill. (1949–53), and completing his novitiate in Bedford, Mass. (1953–54). He was subsequently ordained on 14 June 1958 at the conclusion of his studies at the Maryknoll Seminary in Ossining, N.Y.

As is traditional for all Maryknollers, the end of Father Capodanno’s studies also marked the beginning of his missionary work. Assigned to the island of Formosa [Taiwan] for a period of six years, he worked tirelessly in ministering to its people, learning their customs, and nurturing the Catholic faith among them. Although a far cry from the perilous work he would undertake as a military chaplain, Capodanno’s biographer, Father Daniel L. Mode, has speculated that his experiences during these formative years very much shaped how discharged his duties while in the field. Unable to master the intricacies of the Hakka language spoken by those within his territory, the priest instead became an attentive listener to whom his parishioners could feel comfortable expressing their cares and concerns to without fear of judgment.

After completing his initial missionary assignment in 1964, Father Capodanno was reassigned to Hong Kong the following year, an unusual move given that most Maryknollers were generally expected to minister to the same group of people for the entirety of their lives. Perhaps seeing his transfer as a mark of failure, Father Capodanno repeatedly wrote to his superiors requesting a transfer back to the island. Unable to secure one, he instead sought permission to enlist in the U.S. Navy as a chaplain so that he could serve in Vietnam with a USMC unit. The abruptness of this decision coupled with Capodanno’s sudden fervor surprised many of his friends and fellow missionaries, one of whom even went so far as to describe him as the “last person in the world I thought would be a Marine chaplain.” Nonetheless, his request was granted on 13 August 1965.

It is not wholly clear as to why Father Capodanno suddenly wished to swap his cassock for a flak jacket, though a few potential motivations present themselves. One possibility is that Father Capodanno wished to follow in the footsteps of his brother, James, who had served in the Marine Corps during WWII. Equally important, other Maryknoll missionaries had previously served with distinction as military chaplains, most notably, Father William T. Cummings, who is alleged to have coined the phrase, “There are no atheists in foxholes.” We should not, however, overlook the possibility that this was motivated by deeply spiritual concerns. In an interview for The American Weekend, Father Capodanno stated that he had volunteered because, “I think I’m needed here.” As Father Mode points out, such a statement, though simple enough sounding on the surface, may have been a reference to Maryknoll founder James E. Walsh’s exhortation that a missionary “goes where he is needed but not wanted; and stays until he is wanted but not needed.”

As it turned out, Father Capodanno was both very much wanted and needed. Starting in 1965, U.S. involvement in Vietnam escalated considerably, rising from little over 23,000 military “advisers” at the end of 1964 to nearly 184,000 by the end of 1965. Although the Navy predominantly contributed to this effort by providing air support in the Gulf of Tonkin, river boat patrols (the so-called Brown Water Navy), and naval gunfire support (NGFS) off the coast, its chaplains were often attached to marine units operating in the field. In this respect and many others, they are similar to Navy corpsmen: both often serve ashore, both are allowed to wear Marine Corps uniforms, and both minister to the well-being of those under their care. Indeed, since the very establishment of the U.S. Navy, chaplains have tended to the mental, spiritual, and even medical needs of those who served, regardless of their religious leanings. During WWII, in particular, many Catholic chaplains distinguished themselves in and out of battle, suffering all sorts of privations alongside their flock, whether it was Father Aloysius Schmitt sacrificing himself to save others during the sinking of the Oklahoma (BB-37) at Pearl Harbor, Father Cummings enduring the Bataan Death March, or Father Joseph T. O’Callahan, the first Navy chaplain to receive the Medal of Honor, ministering to the dying and leading firefighting and rescue efforts on board the carrier Franklin (CV-13) after she was hit by two Japanese bombs. Father Emil Kapaun, an Army chaplain, continued this tradition of service and sacrifice during the Korean War, staying on the field with the wounded after the Battle of Unsan (25 October-4 November 1950) and doing his utmost to preserve their health and morale amidst the brutal squalor of a Chinese prisoner of war camp. Now, Father Capodanno would be called upon to do the same.

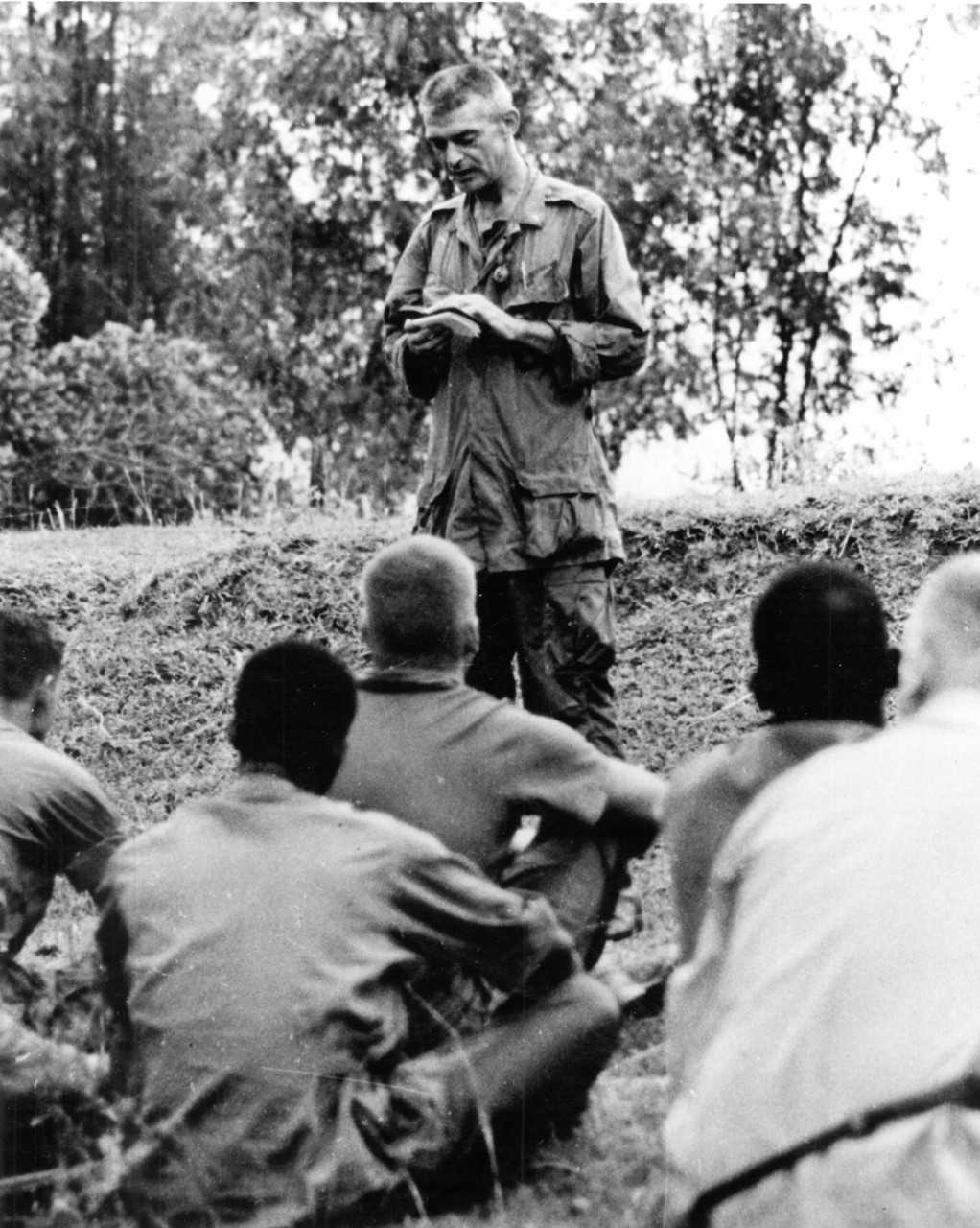

After receiving his commission in the U.S. Navy on 28 December 1965 and attending the Naval Chaplains School, Newport, R.I. (January-February 1966), the newly-minted Lt. Capodanno was assigned to the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division (1/7/1). Although it was highly unusual for someone to go straight from chaplain school to Vietnam without any military experience, Father Capodanno quickly settled in and earned the respect of the marines with whom he served. As the only Catholic priest in the 7th Marines, he made rounds to every battalion, spending the vast majority of his time tending to the needs of the enlisted marines (the so-called “grunts”), regardless of whether or not they were of the Catholic faith. He listened to the cares of the living, administered aid to the wounded, sat from dusk until dawn with the dying, and offered comfort to the friends and the family of the fallen with gentle words and numerous hand-written letters. Despite receiving numerous admonitions from his commanding officer that it was not his job to go on patrols, he had an almost preternatural ability to sneak off with his men, appearing wherever the fighting was hottest and heaviest. He wore no insignia of his rank on his uniform, nor did he shy away from bearing the weight of mud on his boots, a 40-pound pack on his shoulders, or a flak jacket around his lanky frame. When a reporter teased him that wearing a flak jacket was not a good advertisement for his faith, the priest good naturedly responded, “I know it, but it’s protective coloration so I blend in with the men. In addition, I understand their trials better if I accept the same burdens they do.” He went on to note more solemnly, “I want to be available in the event anything serious occurs; to learn firsthand the problems of the men, and to give them moral support, to comfort them with my presence. In addition, I feel I must personally witness how they react under fire—and experience it myself—to understand the fear they feel.”

Father Capodanno would indeed share in these experiences on multiple occasions. During briefings on individual operations, he was in the habit of asking the intelligence officer which company was likely to sustain the highest casualties so that he could place himself in their company. In 1966 alone, he participated in six combat operations, including Operation Rio Blanco (November 20–27), during which he helped to evacuate a wounded captain from the battlefield, all while under heavy fire. On account of such efforts, he received the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Silver Star and the Navy Bronze Star.

On 8 December 1966, Father Capodanno was transferred to the 1st Medical Battalion, which had set up a field hospital near Chu Lai, South Vietnam. Although he strongly desired to stay with marines serving on the front lines and, indeed, continued to seek out every opportunity to minister to them, he took to his new duties with the same degree of vigor and compassion that had earned him the love and respect of the 1/7. As Lt. Joseph L. LaHood, a Navy doctor serving with the 1st Medical Battalion, recalled, “Never had I ever seen such dedication and selflessness, not as a sticky ‘piety’ but as a ‘way.’ For the hundreds of cigarettes he held for the wounded, many of whom could no longer reach their hands to their lips, and for the hundreds of letters he wrote and helped to write for his men, the Marines will never forget that he was one of them.”

By early 1967, Father Capodanno’s deployment was nearing its end. Not wanting to leave “his” marines, he took the unusual step of securing a six-month extension for his tour of duty in Vietnam. He was, however, granted 30 days of leave in April, allowing him time to return stateside to see family and friends. Many of them took note that he had changed greatly since they had last seen him, and that he was often preoccupied with thoughts of the marines who were still over in Vietnam. As his brother, James, recalled “He would be sitting across from us, but his mind was in Vietnam. He couldn’t wait until he got back to Vietnam.”

When Father Capodanno returned to Vietnam, he was assigned to the 1/5 Marines, which was currently battling for control of the Que Son Valley against the North Vietnamese Army (NVA). As he had done during the first part of his tour in Vietnam, he spent much of his time on the front lines, ministering to units that had rarely, if ever, seen a chaplain so far out from the relative safety of command headquarters. He was so dedicated to them that he requested another six-month extension of his tour. When that request was denied, he went so far as to offer giving up his holiday leave, just so he could stay 30 more days with his men. This too was rejected, but that did not stop the dedicated priest from continuing to press for an extension. It was amidst this that he received orders to transfer to the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines (3/5).

On 4 September 1967, a platoon from the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines (1/5) operating in the Que Son Valley encountered a large contingent of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers. In danger of being overrun, they swiftly radioed for reinforcements. In response, the 1st Marine Division launched Operation Swift, sending in company after company to try and saved their beleaguered comrades. When “M” company (M/3/5) received orders to reinforce units already operating in the area, Father Capodanno hopped on the helicopter with them. As they approached, heavy ground fire forced them to land well east of their intended destination, leaving them with no choice but to cover the rest of the distance on foot. En route, they encountered heavy resistance from the NVA.

Father Capodanno, who was safely ensconced in a command post that had been set up over the crest of a nearby hill, could hear the sounds of battle quite clearly but remained there until Pfc. Stephen A. Lovejoy frantically radioed that the 2nd Platoon was in danger of being wiped out. Unable to stand idly by any longer, the determined chaplain ran towards Lovejoy’s position, heedless of the bullets whistling past him. When he reached the beleaguered radioman, he grabbed him by the straps of his bulky AN/PRC-25 radio and pulled him to safety.

This was the first of many missions of mercy that Father Capodanno would undertake. For the leathernecks battling for their lives that day, the “Grunt Padre” proved a sea of calm amidst the raging storm of battle. When tear gas was dropped on the 2nd Platoon’s position, he gave his gas mask to a marine who had lost his. The indefatigable chaplain also continued to risk his life to aid the wounded, rescuing Sgt. Howard Manfra from almost certain death when he lay wounded on a slope that was exposed to enemy machine gun fire. He did not, however, neglect his other important priestly duty, which was to provide comfort to the dying. Among the many marines he provided Last Rites to that fateful day, the most significant may have been Sgt. Lawrence D. Peters, Squad Leader of the 2nd Platoon. Upon seeing that Peters had been mortally wounded, Father Capodanno rushed forward without hesitation, even after being struck in the right shoulder by mortar fragments. When he finally reached Peters’ position, he stayed with him until the young marine succumbed to his wounds. Unbeknownst to the compassionate Padre, the man he held in his arms was a future Medal of Honor recipient.

The wound Father Capodanno had sustained as he rushed to comfort Sgt. Peters was just one many that he received that day. As he raced about the battlefield, mortar fragments struck his arms and legs, and even sheared off part of his right hand, which had so often blessed those under his care. Nonetheless, he refused all medical attention, exhorting the corpsmen to attend to the wounded first. Even as casualties mounted among the 1st and 2nd platoons, he continued to unerringly discharge his duties, delivering what comfort he could to the wounded and dying. One of the last people to see him alive that day, Cpl. Ray Harton, was among those he tended to. Harton, along with two other marines, had been directed by Sgt. Peters to take out an enemy machine gun nest. As they approached, the gun opened fire, killing two of the marines instantly and striking Harton in the left arm. While he lay on the ground bleeding from a gunshot wound to his arm, he vividly recalled that, “As I closed my eyes, someone touched me. When I opened my eyes, he looked directly at me. It was Father Capodanno. Everything got still: no noise, no firing, no screaming. A peace came over me that is unexplainable to this day. In a quiet, calm voice, he cupped the back of my head and said, ‘Stay quiet, Marine. You will be OK. Someone will be here to help you soon. God is with us all this day.’”

After blessing Cpl. Harton with his left hand, Father Capodanno raced over to HM3 Armando G. Leal, who had also been wounded while rushing to Harton’s aid. Aware that the machine gunner who had shot Leal and Harton was still close by, the chaplain is thought to have deliberately interposed himself between the two as he prayed over the wounded corpsman in a bid to protect him. When the machine gun opened fire again, Father Capodanno was struck from behind 27 times, killing both him and HM3 Leal instantly. Five marines attempted to recover the fallen chaplain’s body, but were forced back after three of them were hit by enemy fire. Later that evening, they succeeded in retrieving him. According to Pfc. Julio Rodriguez, “When we found him he had his right hand over his left breast pocket. It seemed as if he was holding his Bible. He had a smile on his face and his eyelids were closed as if asleep or in prayer.”

Father Capodanno’s loss was deeply felt throughout 3/5 and beyond. Even as Operation Swift raged on, his fellow chaplains held a number of small memorial services so that those marines who had served with him could grieve together and find some small measure of comfort. For some, there yet lingered the question as to why Father Capodanno had seemingly been so eager rush into combat and to sacrifice his own life. As Lt. Cmdr. Eli Takesian, ChC, a Presbyterian chaplain and Capodanno’s immediate superior, recalled, “Upon hearing the fatal news [of Capodanno’s death], a young Marine came to me and tearfully asked, ‘If life meant so much to Chaplain Capodanno, then why did he allow his own to be taken?’” Takesian responded, “It was precisely because he loved life—the lives of others—that he so freely gave his own.”

Lt. Vincent Robert Capodanno was buried on 19 September 1967 at St. Peter’s Cemetery on Staten Island. In the months that followed, numerous honors were bestowed upon the fallen chaplain. On 5 February 1968, the Navy Chaplains School at Newport Naval Base, R.I., dedicated its chapel to him, just one of many chapels that are now named in his memory. Ten months later, it was announced that Father Capodanno would posthumously receive the Medal of Honor for his actions on the day he was killed. Secretary of the Navy Paul R. Ignatius presented the award to Capodanno’s brother, James, on 7 January 1969. The medal is now displayed at Capodanno Chapel at The Basic School at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Va., a constant reminder of the “Grunt Padre’s” unerring devotion to those marines under his care.

Although Father Capodanno received the Medal of Honor in recognition of his service and sacrifice on behalf of his country, it must not be overlooked that he was still a priest first and foremost, one who deeply believed that he had been called upon to serve his fellow man. As he noted in his application to the Maryknolls, “All my efforts will be devoted to the people I’m serving. Their lives, both troubles and joys will be my life. Any personal sacrifice I may have to make will be compensated for by the fact that I am serving God.” Such devotion and a willingness to sacrifice on behalf of those he served would not soon be forgotten either by the marines he had tended to or the Church which to which he had dedicated his life. After his death, many of the more devout among his flock (both U.S. Marines and Vietnamese) began praying to him for his intercession on their behalf, with some even claiming to have witness miraculous occurrences after doing so. Consequently, the Roman Catholic Church officially opened Father Capodanno’s Cause for Canonization on 19 May 2002. Two years later, Archbishop for the Military Service, USA, Edward F. O’Brien issued a Public Decree of Servant of God for Father Capodanno, the first of four steps on the path to him being recognized as a saint. Following an intensive investigation of the chaplain’s life, deeds, and writings, Archbishop Timothy P. Broglio opened his Cause for Beatification on 13 October 2013. If it is determined that Father Capodanno lived a life that was heroic in virtue, he will be recognized as a “Venerable Servant of God.” Along with Father Emil Kapaun, he is one of two U.S. military chaplains currently being considered for sainthood with the Roman Catholic Church.

Although there are few honors as prestigious as the Medal of Honor and a Public Decree of Servant of God, the best “official” tribute to Father Capodanno may very well be a fitness report (FitRep) submitted by Lt. Col. Basile Lubka (Commander of 1/7) concerning the chaplain’s service in Vietnam. As Lt. Col. Lubka wrote:

Chaplain Capodanno relentlessly provided the battalion with the solace, comfort, spiritual leadership and moral guidance so essential to an effective infantry battalion. He never spared himself. His dedication to duty will stand as a hallmark to Naval Chaplains everywhere. He exhibited those rare qualities of humanity, selflessness, and humility that are seldom achieved, even by Chaplains. He possessed those intangible qualities which all members of the battalion, officer and enlisted, regardless of religious affiliation, respected. He earned this respect not only as a chaplain, but as a unique human being. He had an uncommon understanding of people and an intimate knowledge of the social and religious customs of Vietnam.

In truth, he was the ‘Padre.’ This was not a perfunctory title, but rather a reflection of the significant respect all hands had for him. This respect was earned by his total and complete willingness to share at all times the risks and privations of all members of the command. He suffered when the men suffered. He was their ‘Rock of Ages.’ Of his own volition, on operations, he deployed with the assault companies because knew his services would be most needed by them. Within the TAOR [Tactical Area of Responsibility], he spent more days and night at company combat bases than within the battalion CP. No problem was too small for him. All hands sought actively his sage counsel. He did not proselytize; he served God, Corps, and mankind in an uncommon, courageous and inspiring way. His name will be legendary to those members who served with him in the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. He was as vital to the operations of the battalion as is close air support and artillery. No Marine could know Chaplain Capodanno and not be an infinitely better human being for it.”

(DE-1093: displacement 4,100; length 438'0"; beam 47'0"; draft 25'0”; speed 27 knots; complement 252; armament 1 Mk. 42 5-inch, 1 ASROC, 4 Mk. 46 torpedo tubes, 1 helicopter; class Knox)

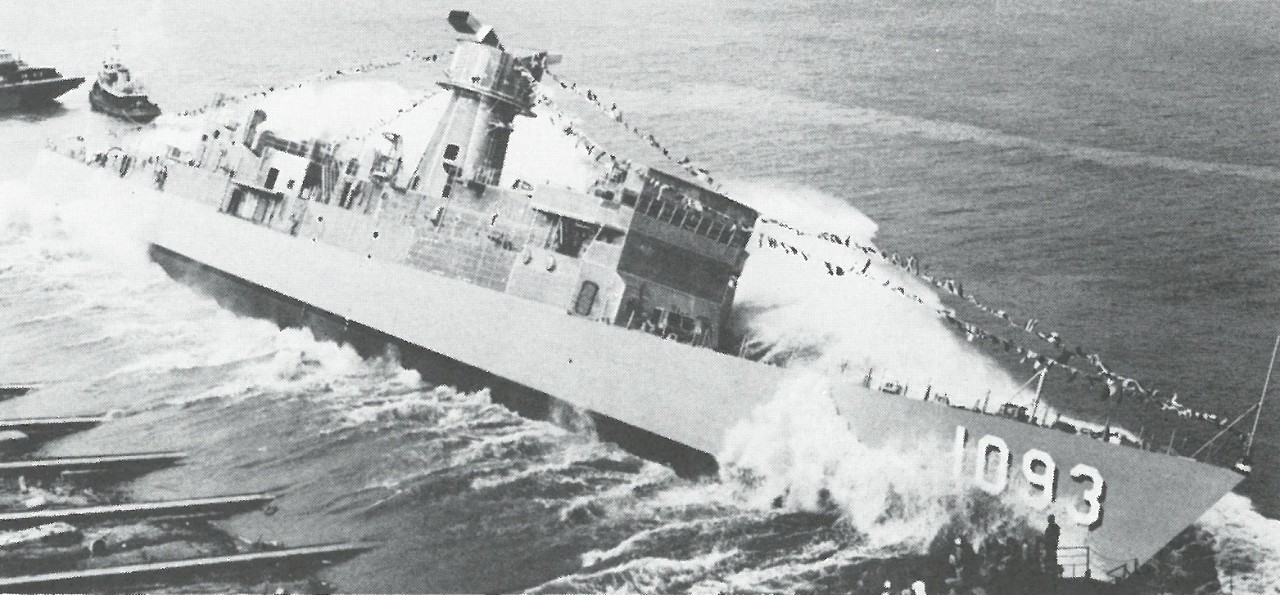

Capodanno (DE-1093) was laid down on 25 February 1972 at Westwego, La., by Avondale Shipyards; launched on 21 October 1972; sponsored by Mrs. Elsie M. Springer, wife of former Rep. William L. Springer (Ill.), and commissioned on 17 November 1973, Cmdr. George W. Horsley, Jr., in command.

The 42nd of 46 Knox-class escort vessels, Capodanno was the first U.S. Naval ship to be commissioned at Mayport, Fl., and the fourth to be named for a chaplain. The decision to name the vessel for Father Capodanno was not entirely without controversy, as some of his fellow Maryknollers were greatly discomfited by the idea of naming a warship for someone who had dedicated his life to the pursuit of peace. Nonetheless, both Capodanno’s family and Monsignor John McCormack, Superior General of Maryknoll, who attended the event along with a contingent of Maryknollers, supported the decision. Chaplain Victor H. Krulak, son of Lt. Gen. Victor H. Krulak, who had served with Father Capodanno at the 1st Medical Battalion Hospital in Chu Lai, was the principal speaker for the event. Perhaps aware of this controversy, Krulak sought to reconcile this inherent tension. As he noted, “It is our hope in the case of destroyers and escorts the ship will take on some of the characteristics of the person for whom the ship is named….I would like to see this ship a strong ship. Taking from her namesake[sic] the strength of character that was able to support the trials of combat without flinching and in doing so support those around him in that trial.” He emphasized to Capodanno’s crew, however, that he would also “like to see this ship a gentle ship manned by gentle men. I hope that this ship will be one always ready to perform a mission of mercy. She will bare [sic] a name that shouts concern for her fellow men. This will be hard to live up to, but I hope that she does.”

Shortly after her commissioning, Capodanno had her 1200 psi engineering plant certified by the Propulsion Examining Board (7 December 1973) and conducted her first light-off (10 December). Onloading her 5-inch/54 caliber ammunition, she briefly got underway for the first time on 13 December to conduct a test fire in order to assess the ship’s structural integrity. Following the holiday leave period, she began her training and inspections in earnest, first steaming around local waters for a short period of operations (8–10 January 1974) and then for noise emissions testing at Charleston, S.C., (22–24 January) and Exuma Sound, Bermuda (26–27 January). After returning to Mayport to onload her ASROC, the ship steamed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba for two weeks of crew refresher training (6–21 February). While operating there, she successfully completed a high speed jet anti-aircraft gunnery exercise (Z-10-AA) on 19 February, a rare feat for a ship of her class. A visit by Rear Adm. Ralph S. Wentworth (Commander Cruiser-Destroyer Force Atlantic) concluded this initial training phase (21 February).

Once she returned to Mayport, Capodanno undertook her final contract trials (24–28 February 1974) before entered her post-shakedown availability. During this seven-month process (March–October 1974), her propulsion fuel system was converted from black oil to the cleaner burning Navy distillate, her flight deck and hanger were enlarged to accommodate a light airborne multi-purpose system (LAMPS) helicopter, and her habitability areas were improved. Upon completion of these improvements, the ship spent all of October conducting her final sea trials, her LAMPS deck certification, and her light-off exam (LOE). She then spent the next month undergoing refresher training down in Guantanamo Bay followed by a successful operational propulsion plant exam (OPPE) in December.

In preparation for her first overseas deployment, Capodanno began 1975 with inspections of her weapons systems (10–15 January) and a work-up of her LAMPS detachment (Anti-Submarine Helicopter (Light) [HSL] 32, Detachment [Det.] 4) in the waters off Jacksonville (15–18 January). She then participated in Composite Training Unit Exercise (CompTUEx) 5-75 (18–27 January), engaging in the sort of task group and LAMPS operations she would be routinely conducting on her deployment. After another month of inspections and preparations, she got underway again for Atlantic Fleet Readiness Exercise (LantReadEx) 2-75 (4–22 March) and a short port visit to San Juan, P.R. (22–24 March). During this period, the destroyer escort conducted anti-submarine warfare (ASW) operations with aircraft carrier Independence (CV-62), participated in gunfire exercises against a surface target, screened amphibious ships during a simulated assault on Vieques Island, P.R., and engaged in an NGFS test at Culebra Island. In all instances, she performed her duties exceptionally, so much so that she would later be awarded the exercise’s “Top Tactical Operator Award” on 30 June, much to the delight of her captain and crew.

Upon returning to Mayport on 27 March 1975, Capodanno underwent one final administrative inspection conducted by Commodore Thomas J. Porcari (Commander, Destroyer Squadron [ComDesRon] 24) (31 March–2 April) and a change of command (4 April) before beginning her pre-overseas movement (POM) phase. During this three-week period, she only briefly left port for an independent ship exercise (17 April) and a dependents cruise (18 April) in local waters. A week after the latter, she finally got underway for her first deployment to the Mediterranean in company with guided missile frigate Luce (DLG-7) and destroyer Stribling (DD-867) (25 April). Together, they rendezvoused with McCandless (DE-1084), Donald B. Beary (DE-1085), and replenishment oiler Savannah (AOR-4) to conduct exercise Trans-Atlantic 2-75.

Arriving in Rota, Spain on 5 May 1975, Capodanno “chopped” to the Sixth Fleet [came under that entity’s operational control] and was assigned to Task Group (TG) 60.2 (Cruiser-Destroyer Group [CruDesGru] 8, DesRon 26). Two days later, she transited the Strait of Gibraltar, conducting exercises and operations with Stribling, Luce, and Bowen (DE-1079) while en route to Palma de Mallorca, Spain, (8 May) and Sardinia (9 May). She then visited Gaeta, Italy (12 May), where she hosted Vice Adm. Frederick C. Turner (Commander, Sixth Fleet). Although she would moor there for less than a day, this would be the beginning of a very long and fruitful relationship between the city of Gaeta and DE-1093. As the ancestral home of the Capodanno family, Gaeta took considerable pride in the ship’s achievements and always warmly welcomed her when she moored in port, inviting her crew to many local festivities including ceremonies honoring Father Capodanno. For her part, Capodanno rarely deployed to the Mediterranean without making at least one visit to the southern Italian city. As one commander of the ship later described it, Gaeta was “our home away from home.”

For the remainder of her deployment, Capodanno operated predominantly in the waters between Italy and Spain. After an extended port visit to Naples (12–24 May 1975), she participated with McCandless and submarine Tullibee (SSN-597) in Sharem XIX (25–28 May), an anti-submarine warfare exercise (ASWEx) in the Balearic Basin. Upon successful completion of this, she conducted an underway replenishment (unrep) with oiler Truckee (AO-147) and visited Ibiza, Spain, in company with McCandless (29 May–6 June). While she lay anchored in port, her LAMPS briefly embarked in Franklin D. Roosevelt (CVA-42) on 30 May to provide plane guard services during the carrier’s night flight operations.

Capodanno left Ibiza on 6 June 1975 and arrived back in Palma de Mallorca that same day. Four days later, she departed in company with Franklin D. Roosevelt, Luce, Bowen, McCandless, and guided missile frigate Leahy (DLG-16) to conduct task group exercises while en route to Malta. The ships engaged in a number of inter-ship drills and training exercises while anchored at Hurd Bank off the coast of Malta (13–16 June), after which they proceeded to Taranto, Italy. It was in the midst of this brief cruise that Capodanno rescued an Italian family whose recreational boat had run out of fuel, leaving them adrift for nearly two days. After disembarking them in Taranto, the ship participated in Dawn Patrol, a multi-national ASW, anti-air (AAW), and anti-surface (ASUW) warfare exercise involving ships from the U.K., Italy, and Turkey (18–29 June). Capodanno’s role was to provide anti-ship missile defense and ASW support for Franklin D. Roosevelt while the group operated in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

At the beginning of July, Capodanno’s designation was changed from DE-1093 to FF-1093 as part of a Navy-wide reclassification of certain ships, with destroyer escorts, or escort vessels, being re-classified as frigates. After spending nearly two weeks in Naples (2–14 July 1975) in tender availability alongside destroyer tender Piedmont (AD-17), the newly-designated frigate got underway in company with Luce and Donald B. Beary for inter-type training and ASW exercises. During the first phase of this, she assumed the role of a modified Soviet Kildin-class destroyer in order to conduct simulated attacks against John F. Kennedy (CV-67) south of Sardinia (16–17 July). This was followed shortly thereafter by task group operations with Forrestal (CV-59), Leahy, Donald B. Beary, and Nautilus (SSN-571). After anchoring in Augusta Bay for three days (18–20 July), the frigate departed in company with Forrestal, Luce, guided missile cruiser Wainwright (CG-28), and Donald B. Beary for additional operations and an extended port visit to Taormina, Italy, on 25 July. While the ship lay moored in the Sicilian coastal city, members of the Capodanno Cougars baseball team defended their vessel’s and their nation’s pride by defeating a team from Giardini, Sicily. Victory was not, however, assured on the diamond until the very last pitch, with the final score being 16–15 in favor of the Cougars (4 August).

Capodanno’s crew would be tested in a very different manner just a few days after her triumph on the baseball diamond. Departing Taormina on 8 August 1975, she encountered the Liberian freighter Brilliant sinking just 35 miles off the coast of Sicily. To the frustration of the frigate’s captain and her crew, Brilliant’s master refused all offers of assistance until he and the rest of the crew were finally forced to abandon ship. Rescuing the freighter’s bedraggled seamen from the grasping waters of the Adriatic, Capodanno sailed to Augusta Bay and disembarked them. Cmdr. Robert D. Frey felt justifiable pride of his crew’s performance during this mission of mercy, but he was profoundly troubled by the fact that he had not been permitted to intervene earlier when there was still a possibility of saving the sinking vessel. Lloyd’s of London, which was investigating Brilliant’s insurance claims, shared his befuddlement, so much so that they contacted the U.S. Navy for permission to collect a statement from the commander. Although neither party every explicitly said so in their communications, it seems quite clear that both harbored the suspicion that Brilliant may have been deliberately allowed to sink.

Regardless of whether or not she had been enlisted to serve as an unwitting accessory to insurance fraud, Capodanno was soon back underway to participate in exercise National Week XVIII (10–13 August 1975). After briefly stopping in Augusta Bay for a post-exercise discussion with the other participants (14–15 August), she steamed to Valencia, Spain for a lengthy port visit (18–30 August) followed by a training anchorage at Pollensa Bay in Mallorca (30 August–3 September). En route to her next destination, a small class B fire broke out in, of all places, the frigate’s fire room. Fortunately, the crew swiftly extinguished the blaze before it could cause significant material damage or casualties, thus allowing their ship to arrive in Ibiza safe, sound, and slightly singed (4–10 September). A week later, she was once more plowing the waves of the Mediterranean, conducting an underway replenishment with Savannah and cruising to Palma de Mallorca for another week-long port visit (11–17 September).

In the two days following her port visit, Capodanno engaged in ASW exercises with Spadefish (SSN-668) and other members of her task group (18–19 September 1975) and then sailed to Porto Scudo in Sardinia for a training anchorage (20–23 September). While transiting from the island to the Italian peninsula, the frigate participated in another ASW evolution, this time with a French submarine east of Sardinia. She was then supposed to visit Civitavecchia, Italy, but steam leaks in the main engine steam chest forced her to instead put into Naples for an impromptu restricted availability (24 September-8 October). It took over two weeks to fix the problem, forcing the ship to rendezvous with her task group at Castellammare, Sicily, and then immediately get underway for Rota, where she would conduct her turnover with Ainsworth (FF-1090) and Aylwyn (FF-1081) (11–13 October). From there, she crossed the Atlantic in company with her task group and returned to her home port (23 October). Owing to the length of her deployment and the technical difficulties she had experienced, the vessel entered a prolonged period of upkeep and restricted availability that lasted until March 1976.

Upon completion of her restricted availability, Capodanno began preparations for her next deployment, undergoing a battery of tests including a surprise maintenance and material management (3M) inspection. In April, she sailed for Bloodsworth Island in the Chesapeake Bay to conduct her NGFS exam, but was unable to complete it due to an issue with her gun mount. This would be the least of her issues going forward. On 10 May, she got underway for her deployment to West Africa and the Middle East, rendezvousing with Donald B. Beary en route. The first part of the deployment went smoothly enough, with Capodanno making port visits to Conakry, Guinea, (21–24 May) and the Gambia (26 May). While at the latter, she even had the privilege of hosting President Dawda Jawara. Difficulties arose, however, once she moved into the Mediterranean. Shortly after she transited the Strait of Gibraltar, on approximately 5 June, the frigate experienced a crippling engineering casualty that made it necessary for Donald B. Beary to tow her part of the way to Naples. Salvage ship Recovery (ARS-43) subsequently assumed these duties on 7 June, successfully bringing the crippled vessel into port two days later (9 June).

Fortunately, Capodanno’s engineering problems did not detain her for long. By 17 June 1976, she was back underway to join the Middle East Force for operations in the Indian Ocean and North Arabian Sea. While operating there, she had the opportunity to participate in celebrations for Seychelles’ newly granted independence (29 June) and to fire a 21-gun salute in honor of the U.S.’s own Bicentennial (4 July). Two weeks later (19 July), however, the ship again required assistance from Donald B. Beary, having run low of fuel. They conducted an unrep (a rarity for two frigates at this time) and then then proceeded to Bahrain for upkeep, arriving on 29 July. More operations in the Indian Ocean ensued, including near Kenya (26–27 August), where Capodanno, for once, was not the ship in desperate need of assistance. Instead, it was three Kenyan gunboats that had been significantly damaged by heavy seas. After rendering assistance to them, the frigate visited Bandar Abbas, Iran, during which she hosted a tour for Capt. Shahriar Shafiq, nephew of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, on 8 September 1976. As her deployment wound down, Capodanno celebrated a major milestone in the life of any ship, her 1,000th helo landing (8 October 1976). She then conducted a turnover with Pharris (18 October) and sailed back to Mayport, arriving on 9 November 1976. Save for ASW exercises in December, she spent rest of the year in her homeport.

The first half of 1977 continued to be a relatively quiet period for Capodanno, with January largely spent undergoing sea trials near Jacksonville and inspections while in port. At the end of February, she cruised northwards along the Eastern Seaboard and made a visit to Staten Island (25–27 February). While moored there, Father Capodanno’s sister invited some of the crew to have dinner at her home, during which, they told many tales about the ship and even sung a few songs about it. One made a particularly strong impression:

The story’s about a hero

A man of courage and fame

Vincent Capodanno

That was the hero’s name

Capodanno was a man of God

Under the Vietnam sky.

His mission was to help mankind

And that is how he died.

Although he’s gone

His memory lives on

All across the ocean

In a song.

If he could see

O how proud he would be

To have a ship in his name

And memory.

That’s Capodanno

FF-1093

Following this evening of merriment, the fighting frigate and her cadent crew sailed farther north to Newport, R.I., where they provided services (and, quite possibly, singing lessons) to the Surface Warfare Officers School Command for four days (1–4 March 1977). Returning to Mayport, the ship underwent maintenance and inspections over the next three months, most notably, a nearly month-long intermediate maintenance availability (IMAV) (13 June-8 July). She finally got underway for a sustained period of operations on 25 July, completing her OPPE en route to Roosevelt Roads, P.R.

A week after she arrived at Roosevelt Roads (29 July 1977), the ship deployed on UNITAS XVIII. Conducted annually, these multinational exercises involve ships from the U.S. and numerous countries in Central and South America. Getting underway in company with Mahan (DDG-42) and Vreeland (FF-1068), she first visited Santa Marta, Colombia, (7–10 August), conducted operations with units from the Colombian Navy (10–12 August), and then concluded this phase of the UNITAS with a visit to Cartagena, Colombia (11–14 August). The group then transited the Panama Canal (17–19 August) and sailed to Salinas, Ecuador, where Capodanno had the privilege of hosting Vice Adm. Alfredo Poveda, then serving as the head of Ecuador’s military government (22 August). Such pleasantries eventually gave way to more operations, this time with ships from the Peruvian (27–30 August, 4–5 September, 7–10 September) and Chilean navies (7–10, 12–16, 22–4 September). In between these operations, the group visited Ilo, Peru, (31 August) and the Chilean cities of Valparaiso (17–21 September), Talcahuano (24 September–2 October), and Punta Arenas (6–8 October), hosting numerous dignitaries, holding tours, and providing Project Handclasp materials.

Rounding Cape Horn and proceeding northwards, Capodanno and her group visited Montevideo (14 October) and Punta del Este (15–18 October), Uruguay, after which they conducted combined operations with members of the Uruguayan and Brazilian navies (19-24 October). Following a port visit to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, (25–30 October) and further operations with units from the Brazilian Navy (31 October–3 November), the group concluded the Unitas with a series of visits to Salvador, Brazil, (4-7 November), Trinidad and Tobago, Port of Spain (16–18 November), Puerto La Cruz, Venezuela, (20, 29 November), La Guaira, Venezuela, (24-27 November) Willemstad, Netherlands Antilles (1–4 December), and Roosevelt Roads (7 December). She finally arrived back in Mayport on 10 December and began preparations for her regular overhaul (ROH) (15 December). Following her holiday upkeep, the frigate sailed north to offload her ammunition in Earle, N.J. (25 January 1978) and then moored at Bath Iron Works at Bath, Maine.

Capodanno’s overhaul was not completed until 19 December 1978. By this time, her homeport had changed from Mayport to Newport, R.I. Although a change in homeport is not unusual in the life of a naval vessel, this one carried with it special significance, as the Navy had not based any ships in Newport since decommissioning the nearby Quonset Point Naval Air Station and transfer of Cruiser-Destroyer Force Atlantic to Norfolk, Va., in 1974. This had been a major blow to the local economy, one which Newport was only just beginning to recover from when it was announced that Capodanno and three other naval frigates would be homeported there. With the arrival of the former on 20 December, the city once again became a permanent homeport for active duty Navy ships.

Capodanno spent the first two months of 1979 in upkeep and undergoing preparations for OPPE. At the beginning of March, she sailed southwards, first to Port Everglades, Fl. (3–5 March), and then to the Atlantic Underseas Testing and Evaluation Center (AUTEC) for her weapons systems acceptance trials (WSAT) (7–10 March). She then steamed to Guantanamo Bay for two phases of refresher training (13–30 March, 3–20 April) separated by a brief port visit to Port au Prince, Haiti (1-2 April). Once her refresher training was complete, the frigate departed for Roosevelt Roads, where she undertook her NGFS qualifications (23–24 April) and completed her OPPE (26-27 April).

Returning to Newport on 2 May 1979, Capodanno stayed busy for the next two months with upkeep and inspections, including her Board of Inspection and Survey (InSurv) (7–11 May), an IMAV with Yosemite (AD-19) (14 May–8 June), and a ship exercise in Narraganset Bay (11–15 June). On 10 July, she participated in ReadiEx 2-79, a multi-week exercise intended to prepare her for her first overseas deployment since 1976 (10 July–2 August). Following a month in Newport (6 August-6 September), she transited the Atlantic and reached Rota on 18 September for a four-day port visit. She subsequently conducted operations in the West Basin (22–24 September) and the Tyrrhenian Sea (25 September) en route to Naples for upkeep (26–31 September). Six days later, the ship got underway for more operations, most notably, participating in Display Determination ’77, a NATO exercise taking place in the Ionian Sea and off Turkish Thrace (2–9 October).

Capodanno spent ten days in Catania for more upkeep (10–19 October 1977) before cruising to Augusta Bay for a training anchorage (20–21 October). She next traveled to Palma de Mallorca for more upkeep (26–30 October) and Rota (31 October) in advance of CrisEx ’79, a joint naval amphibious exercise with the Spanish military involving over two dozen ships and 35,000 troops intended to practice repelling an invasion along Spain’s Mediterranean coastline. Once this was complete, the ship returned to Naples, spending most of November in restricted availability (7–27 November).

Upon the completion of her restricted availability, Capodanno shifted to a training anchorage at Cagliari, Italy (1–2 December 1979) and then commenced operations in the Tyrrhenian Sea on 3 December. Following a period of upkeep in Reggio di Calabria, Italy (10–15 December), she participated in a multi-carrier group exercise (MultiPlEx 1-80) involving a mock battle between the Nimitz (CVN-68) and Forrestal battle groups (16–20 December) and then spent the rest of the year in upkeep in La Spezia, Italy (21 December 1979–5 January 1980).

For the rest of her deployment, Capodanno predominantly operated in the Central and Western Mediterranean. Getting back underway on 5 January 1980, she spent nine days alternating between the Ionian (6–11 January) and Tyrrhenian seas (12–13 January) and then visited Genoa for another two weeks of upkeep (14 January–3 February). She subsequently cruised to Tunis, Tunisia (6-10 February) and then Toulon, France, where she spent most of February in another period of Restricted Availability (15–29 February). Once back out to sea, she made straight for Naples, anchoring there for four days (2–5 March) in preparation for National Week XXVIII, another joint exercise between ships from the U.S. and European navies (6-14 March). Finally, the ship visited Malaga, Spain (15–17 March), and Rota (21–22 March) en route back to Newport. Having spent close to seven months overseas, she would remain in her home port for over a month (2 April–5 May).

Once her post-deployment leave and upkeep ended, Capodanno sailed to Bloodsworth Island to conduct her NGFS testing (8 May). She was then supposed to participate in joint forces exercises Solid Shield ’80 (12–13 May), a sea-air exercise that involved a simulated assault on Guantánamo Bay. Not surprisingly, the Cuban government considered this to be a rather provocative gesture and raised fierce objections to it. U.S.-Cuban tensions were already rising over the mass emigration of Cubans to the U.S. (the so-called “Mariel Boatlift”) and there was a very real fear on the part of the Cuban government that the exercise was just a cover for an actual invasion of the island. Ultimately, President Jimmy Carter canceled the exercises after the Panamanian president also raised objections to it.

With no further operations to undertake, Capodanno returned to Newport for two weeks (17 May–1 June) before entering General Dynamics Shipyard in Quincy, Mass., for a nearly two-month SRA (3 June–30 July). Once this was complete, she got underway to onload munitions at Earle (5–7 August) and to make a brief port visit to Norfolk (9–11 August). Upon returning to her homeport, she began her POM preparations for NATO exercise Teamwork ’80, a simulated assault against northern Europe. While en route (29 August–9 September), the frigate participated in a preliminary exercise, United Effort ’80, in order test her ability to protect transatlantic convoy routes from surface and submarine attacks. Once she had safely made it across the ocean, she visited a number of different ports while the exercise was taking place, including Copenhagen, Denmark (24–30 September), Oslo, Norway (2–6 October), Leigh, Scotland (8-12 October), Rosyth, Scotland (13 October), and Antwerp, Belgium (15–20 October). At the exercise’s conclusion, she returned to Newport (3 November) and remained there for the rest of the year, save for two brief periods of independent operations in Narragansett Bay (24–26 November, 8–10 December).

The year 1981 proved no less busy for Capodanno than the previous twelve months. At the end of her holiday leave, the ship departed Newport to conduct operations in the western Atlantic (12–15 January) and a port visit to Fort Lauderdale (16–19 January). She returned to Newport not long after and spent the next two months mainly in port undergoing upkeep and training (23 January–19 March). Once she finally got back underway on 20 March, she again steamed southwards, this time conducting a short circuit through St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands (24–26 March) and Bermuda (29–30 March). Upon returning to Newport on 3 April, she underwent nearly a month of combat system review and maintenance availability.

At the beginning of May, Capodanno participated in Solid Shield ‘81off the Eastern Seaboard (1–12 May 1981) and then paid a visit to Father Capodanno’s hometown of Staten Island (16–17 May) on her return journey. Upon arriving back in Newport, she commenced her pre-deployment upkeep (19 May–14 June) in preparation for Unitas XXII. Departing Newport on 15 June, she first stopped at Roosevelt Roads (21–22 June) and then proceeded to conduct port visits to the islands of Anguilla (29 June-1 July), Montserrat (1–3 July), and Antigua (3–6 July) in the British West Indies. From there, the frigate sailed to Venezuela to conduct her first round of Unitas operations with the Venezuelan Navy (11–13 July), as well as a port visit to La Guaira, Venezuela (8–11 July). Following a refueling stop at Puerto Cordon, Venezuela, she participated in joint operations with units from both the Venezuelan and Colombian navies, as well as port visits to Cartagena (19–21 July) and Maracaibo, Venezuela (23–25 July).

The next phase of UNITAS XXII saw Capodanno predominantly operating off the coast of Brazil, first with ships from the Columbian, Venezuelan, and Brazilian navies (26 July–2 August 1981), and then with just the latter (5–11 August). After two separate visits to Salvador, Brazil (3–4, 12–15 August), she conducted further operations with the Brazilian and Venezuelan navies (16–18 August) and then moored in Rio de Janeiro for over a week (19–26 August). At the end of the month, she made her way to Montevideo (2-8 September) in company with Uruguayan naval vessels (26 August–1 September), and then sailed down Argentina’s coast in company with some of their own ships, visiting Puerto Belgrano (10–18 September) and Punta Madryn (24–26 September) en route.

Capodanno began the month of October with a brief visit to Punta Arenas, Chile (1 October 1981), followed by a transit of the Strait of Magellan and the Chilean Inland Waterways. Following visits Puerto Montt (3 October) and Talcahuano, Chile (5–10 October), she alternated between operations with members of the Chilean Navy (10–12, 19–22 October) and port visits to Valparaiso (12–19 October) and Antofagasta (23–25 October). She then cruised up the coast to Peru, sailing in company with members of the Peruvian Navy and mooring in Callao (28–31 October) and Paita (12–13 November). For the final phase of UNITAS, the frigate operated with ships from Ecuador (14–15 November) and made visits to Guayaquil (16–18 November) and Manta (20-22 November).

With UNITAS XXII finally complete, Capodanno commenced her long voyage home. After mooring in Rodman, Panama, for a few days of upkeep (25–27 November 1981), she transited the Panama Canal and subsequently participated in exercise Allied Carib II, visiting Aruba (3–5 December) in between operations in the Caribbean Sea with the Dutch and Venezuelan navies (29 November–2 December, 5–7 December). Once this was complete, she steamed to Roosevelt Roads to conduct both an NGFS test (8 December) and upkeep (9–10 December). The ship finally got underway for Newport on 11 December, arriving five days later (15 December) to being the normal period of holiday leave and upkeep.

As busy of a year as it had been, 1981 was not without its rewards for Capodanno and her crew. While she was operating off the coast of Argentina, a singular honor was being prepared for her across the Atlantic Ocean. In remembrance of Father Capodanno on the 14th anniversary of his death, Pope John Paul II issued his apostolic blessing to the ship and her crew. Such an honor had never been accorded to another U.S. naval vessel (though Pope Pius IX had blessed some of Constitution’s crew during a visit on board in 1849), something which the ship’s commanders were more than happy to point out when discussing her.

The blessed vessel did not get underway again until 1 February 1982. When she finally did, it was only for a short cruise to Yorktown (2–4 February) to offload her ammunition. Not long after she returned to Newport (5–16 February), however, Capodanno sailed to Boston, Mass., where she a commenced an approximately two-month long SRA to upgrade her sonar and undertake a number of repairs (16 February–27 April). When she finally left the shipyard, she steamed to Earle to onload her ammo and then returned to Newport on 30 April. With the exception of an NGFS test in June at Bloodsworth Island (10–12 June), the frigate spent the next three months alternately moored in port and operating locally in Narragansett Bay. It was not until the end of July that she left her local waters for Norfolk in order to undergo training and her combat systems readiness review (19 July-1 August). When she returned to her homeport on 4 August, more inspections ensued including an INSURV and OPPE.

By September 1982, preparations were well underway for Capodanno’s upcoming deployment to the Mediterranean. Although she spent the majority of the month operating in and around Newport, she did briefly sail to Fischer’s Island, N.Y., to conduct checks at the Fleet Operational Range for Acoustic Calibration Systems (FORACS) (20–21 September). A week later, she embarked HSL-32 Det. 7 (27 September) and then set a course for Puerto Rico to participate in ReadEx 3-82 (1-14 October), stopping at Earle to onload her ammunition en route (29–30 September. During the exercise, she underwent self level noise tests at St. Croix, U.S.V.I., unreps with Kalamazoo (AOR-6), a gunnery exercises at Vieques, and an ASWEx with Lapon (SSN-661). She then returned to Newport on 16 October to undergo her final set of inspections prior to deploying on 22 November.

In comparison to her prior deployments to the Mediterranean, this one would require far more of Capodanno than simply conducting port visits and joint exercises across the Mediterranean. Earlier that year, on 6 June 1982, Israel had launched an invasion of southern Lebanon with the aim of driving out Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) fighters. A two-month siege of Beirut ensued until the U.S. brokered an agreement to allow Syrian and PLO fighters to evacuate under the supervision of a multinational peacekeeping force consisting of British, French, U.S., and Italian troops. Although they had planned only to send a limited number of troops to ensure that both sides adhered to the terms of the peace agreement, continuing hostilities in the region coupled with the fragility of the Lebanese government led the member countries of this force to commit even greater manpower and resources to ensure peace within the region. While much of this commitment was to be fulfilled by U.S. ground forces (mainly marines), Navy ships such as Capodanno were needed to perform NGFS duties off the Lebanese coast. From 7 to 14 December, she did just that.

This was not the only assignment that Capodanno would undertake while in the Mediterranean. When not in port or on station off Lebanon, she was busy conducting ASW patrols throughout the Mediterranean, often in company with Nimitz. The first of these took place in the final weeks of 1982 (14–30 December), after which she briefly returned to her NGFS duties off the Lebanese coast (30 December 1982-1 January 1983) and then set a course for Toulon. Following two weeks in port for upkeep (7–22 January), she was back underway in company with Nimitz for an additional ASW patrol (22 January-1 February). Upon refueling at Augusta Bay on 1 February, the frigate briefly returned to the firing support area near Beirut (4–5 February), but was soon called away to Cape Andreas, Cyprus, to monitor Soviet vessels in the area (6–10 February). She then sailed to Alexandria, Egypt, in company with Mississippi (CGN-40) (11 February).

Capodanno was supposed to spend four days in Alexandria, but on 13 February, she was ordered to return to the Lebanese coast to plane guard Nimitz the next day. The carrier group temporarily departed on 17 February to search for a Soviet Foxtrot-class submarine and a Kashin-class guided missile destroyer, returning on 22 February for another 12 days on station (22 February–5 March). Although this would be Capodanno’s final stint off the Lebanese coast, there was still plenty left to do before her deployment was over. Returning to Augusta Bay to replace a damaged AN/SWS 35 variable depth sonar (VDS) cable, she spent the next six days streaming her tactical array sonar (TACTAS)/VDS off the coast of Sicily as part of an ASW patrol with Edward McDonnell (FF-1043) (10–15 March) and then sailed to Gaeta to undergo an IMAV alongside Puget Sound (AD-38) (16-28 March). Once this was complete, the frigate resumed her ASW patrol of Sicilian waters for 15 days (28 March–12 April) and then sailed to Toulon for nine days of liberty (14-22 April). For her next assignment, she was supposed to conduct ASW operations in the Tyrrhenian Sea (23–24 April), but this was cut short when a crack was discovered in the ship’s stub mast, forcing her to return to Gaeta to conduct another IMAV with Puget Sound (25–27 April). Afterwards, she sailed to Palma de Mallorca (29 April–2 May) for her final port visit prior to her transit through the Strait of Gibraltar. It was during the latter that she participated in Operation Locked Gate, a simulated blockade of the strait intended to prevent Soviet subs and ships from entering the Atlantic in the event of war (3–10 May).

With her deployment complete, Capodanno returned to Newport and promptly commenced a month-long period of leave and upkeep (20 May–20 June 1983). Following this, she operated in Narragansett Bay for five days (20–24 June) and conducted a dependents’ cruise to Bristol, R.I., to participate in the city’s Independence Day festivities (2–5 July). She subsequently visited Albany, N.Y., for a public relations visit (8–12 July) before returning to Newport. For the next month (13 July–9 August), the frigate’s crew worked feverishly to prepare her for upcoming regular overhaul. Getting underway on 9 August, she offloaded her ammunition at Earle (9–11 August) and then cruised to Bath Iron Works on 12 August to commence the overhaul. During this process, she spent nearly two months in dry dock for work on her hull and sonar dome (11 October–1 December).

Eight months, 17 million dollars, and one change of command later, Capodanno completed exited Bath Iron Works ready to resume active service (6 April 1984). After onloading her ammunition at Earle (10 April), she returned to Newport, where she spent two more months in port (12 April–10 June). It was not until mid-June that she began to ramp up her at-sea operations, first conducting two separate underway periods in Narragansett Bay (11–15 June, 26–28 June) and then cruising southwards to Port Everglades (9–13 July), stopping at Earle en route (10 July). Following a four-day port visit at Port Everglades (13–16 July), she steamed to AUTEC to conduct weapons system testing and then returned for another three days in port (21–23 July). As is often the case following an overhaul, the frigate then sailed to Guantanamo Bay for a month of refresher training and her OPPE (26 July–29 August) coupled with NFGS qualifications at Vieques and noise measurement testing at St. Croix (1–3 September). Upon completion of this, she visited Roosevelt Roads (3-6 September) and then returned to Newport on 12 September.

Capodanno would spend over a month in port, getting underway only briefly for local operations (22–26 October, 28 October–2 November 1984). On 3 November, she departed for the North Western Atlantic in support of strategic objectives. Save for brief stop in Bermuda to make repairs (14-15 November), she was at sea for almost an entire month. At the end of operations, she spent eight days in Norfolk for a training availability (7–14 December) and then made her return to Newport for holiday leave and upkeep (16 December 1984–9 January 1985). Even after the end of this period, the ship largely spent most of January in port for upkeep and training, leaving for only a four-day period of local operations (19-22 January). She finally got underway again on 7 February, cruising to Norfolk for yet another training availability and a surface ship safety review (11–15 February). From there, the frigate charted a course that included port visits to St. Croix (20–21 February), Port Everglades (1–2 March), and St. Thomas, U.S.V.I. (11–13 March), ASW operations at the AUTEC Range (26–28 February), and a swing through Roosevelt Roads (8 March) and Vieques (9–10 March) for an NGFS exercise.

After she arrived back at Newport on 19 March 1985, Capodanno commenced a month-long IMAV (19 March–19 April), followed by three months largely spent in and around Newport conducting training and upkeep in preparation for her OPPE (29–30 July). Once this was complete, she steamed to Puerto Rico to participate in ReadEx 3-85 (14 August–7 September). Immediately upon her return to Newport, she commenced her POM phase (8 September–1 October), leaving port only briefly to evade a hurricane (27–29 September). On 2 October, she departed Newport to rendezvous with the Coral Sea (CV-43) Battle Group for another deployment to the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean.

The first months of Capodanno’s deployment proved largely routine. Upon arriving in the Mediterranean and chopping to the Sixth Fleet, she performed ASW screening duties for her battle group (14–19 October 1985), conducted an NGFS exercise with units from the U.S. and Turkish navies at the Gulf of Saro (20 October), and made an enjoyable but rather uneventful visit to Haifa, Israel (28 October–11 November). By the end of November, she had transited the Suez Canal (13–14 November) and spent nearly two weeks conducting operations in the Gulf of Aden (15 November–1 December) as part of Saratoga (CV-60)’s battle group. After a brief anchorage at Masirah Island, Oman (3–4 December), she conducted additional ASW screening operations (5-10 December), visited Diego Garcia, British Indian Ocean Territories (14–15 December), and spent the holidays at Singapore (23–28 December). She rang in the New Year en route to Chittagong, Bangladesh (2–5 January 1986).

Capodanno might very well have spent the rest of her deployment steaming around the Indian Ocean, but she and the rest of her battle group were suddenly ordered to return to the Mediterranean for freedom of navigation operations off the coast of Libya. Since 1973, Col. Muammar Gaddafi had asserted that the Gulf of Sidra was within Libyan territorial waters up to the 32°30’ north parallel. Although such claims were well beyond what was permissible under international law, neither the U.S. nor its allies could freely dismiss them as sheer bluster. Throughout the 1970s and 80s, Col. Gaddafi had built up Libya’s armed forces significantly, purchasing a considerable number of aircraft and ships from the Soviet Union, all with the intention of asserting his hegemony over North Africa and taking a leading role in the affairs of the Arab world. To further these aims, he also engaged in more subversive tactics, training terrorist groups and using his own agents to undermine rival governments and sow terror across the West.

In response, the U.S. undertook a number of measures to counteract his growing influence and undercut his ideological and territorial claims, not the least of which was conducting exercises in the Gulf of Sidra in order to give the Libyan leader a close-up view of U.S. naval might and to assert its ships’ right to navigate freely throughout the gulf. Such operations were not without risk. Although the U.S. commanded superior firepower, the Libyans still responded aggressively to any exercises within the gulf. The most prominent example of this occurred on 19 August 1981 when two Soviet-built Sukhoi Su-22’s (NATO codename: Fitter) fired upon and were subsequently shot down by two Grumman F-14 Tomcat fighter jets while Nimitz and Forrestal were conducting air exercises,

Since that time, Libya had stepped up its support for terrorist organizations such as the one overseen by Palestinian terrorist Abu Nidal, as well as utilizing its own independent hit squads. In late 1985, a wave of terrorism swept across Europe and North Africa culminating in bloody rampages at airports in Rome and Vienna on 27 December. Believing Libya to have, at the very least, aided and abetted the perpetrators, President Ronald Reagan ordered a show of force in the Gulf of Sidra, hoping that it would, coupled with strong economic and diplomatic sanctions, dissuade Gaddafi from offering any further support for terrorism. Failing at that, the U.S. was prepared to retaliate against strategic targets in Libya.

In order to accomplish this without sustaining any casualties, it was determined that it would be necessary to send multiple carrier groups to the Gulf of Sidra. Consequently, Saratoga received orders to return to the Mediterranean with all due haste. Getting underway on 5 January 1986 Capodanno and the rest of her group rendezvoused with the Coral Sea Battle Group on 15 January. For the duration of the crisis, the two carrier groups, soon to be joined by the America (CV-66) Battle Group, would operate in unison as part of Task Force (TF) 60, with Capodanno shifting back to the Coral Sea Battle Group. It would be her job to escort the carrier during operations, provide ASW support in the event of a conflict, and help to recover any planes that failed to land safely on the carrier’s deck. All of this would greatly test her capabilities and those of her crew, particularly since the frigate had never actually been in a live combat situation.

On 26 January, Capodanno and the rest of TF 60 entered the Gulf of Sidra for exercise Attain Document I, the first of three planned exercises in the gulf. Sometimes referred to within the Sixth Fleet as “Operations in the Vicinity of Libya” (OVL), these operations were intended to enforce freedom of navigation with the gulf and to assess Gaddafi’s response to such actions. The first two would operate just north of the 32°30’ north parallel, while the third would cross what Gadaffi had dubbed “The Line of Death.” Both Attain Document I (26–30 January) and Attain Document II (12–15 February) proceeded without incident. Although the Libyans greeted their unwanted American guests with fighter jets, U.S. pilots swiftly intercepted them and ensured that no opportunity arose to launch a surprise attack.

When not engaged in these exercises, Capodanno was able to visit a number of ports within Italy including Naples (1–10 February 1986), Ancona (18–26 February), and Taranto (5–12 March), as well as participate in NATO exercise Sardinia 86. Once America Battle Group joined TF 60 on 19 March, however, it was time to return to the Gulf of Sidra and commence Attain Document III, the final and most dangerous phase of the exercise. Whereas the first two exercises had avoided crossing the “Line of Death,” the third one would do so knowing full well that it might provoke a hostile reaction from the Libyans. While it was not the Reagan administration’s intention to start an all-out war with Libya, it was hoped that chastising Gaddafi would dissuade him from instigating further terrorist attacks abroad and perhaps even undermine his control of Libya. To that end, the group sailed into the Gulf one hour into the mid watch on 23 March (0100), with aircraft making their first pass over the “Line of Death” at 2015. The Libyan’s SA-5 Gammon missile batteries locked on to any aircraft that came within range, but held their fire until 1200 on 24 March when they fired upon two F-14’s from fighter squadron (VF) 102. Fortunately, the F-14’s had plenty of warning to take evasive maneuvers while the nearby Northrop Grumman EA-6B Prowlers jammed the Libyans’ fire control radar, preventing the missiles from doing anything aside from disturbing the local fish when they plunged harmlessly into the gulf. Despite this naked act of aggression, Adm. Frank B. Kelso II held off giving the order to retaliate against all Libyan units until it had been confirmed that the missile launches had been intentional. Once this had been done, the retaliatory phase of the exercise, Operation Prairie Fire, commenced. Over the next day, U.S. forces would not only destroy the offending missile battery, but also a La Combattante II-G-class fast missile attack ship and a Nanuchka II-class guided missile corvette, all without suffering a single casualty. They even had the opportunity to test out their Harpoons on live targets for the first time ever.

After two more days, the ships departed the Gulf of Sidra on 27 March 1986. Believing they had pacified Gaddafi, the Coral Sea Battle Group sailed to various ports around the Mediterranean for a few well-deserved days of liberty prior to the long transatlantic voyage back to its units’ homeports. Capodanno made yet another stop at Father Capodanno’s ancestral home of Gaeta (30 March–2 April), where she was presented with a plaque honoring her namesake by the Italian-American Committee of Gaeta. She then cruised to Barcelona (4–7 April) for what was anticipated to be her final port visit of the deployment. Once again, however, an act of terrorism altered her plans. On 5 April, a bomb exploded in a West Berlin discotheque, killing three (two of them U.S. soldiers) and wounding 229 others. The choice of location was not accidental, as the club was heavily frequented by U.S. soldiers. U.S. intelligence agencies immediately suspected Libyan involvement in the attack, and soon enough, they had firm evidence linking the two. Consequently, the Reagan administration began drawing up plans for retaliatory strikes.

Although there was considerable support for such strikes in the U.S., many European countries and their citizens were less than enthused, believing that any U.S. actions against Libya would only stir up more violence. A number of countries such as France and Spain closed their air space to U.S. strike forces and anti-war protests erupted across the continent, including in Barcelona. Prior to Capodanno’s departure on 7 April, members of the Catalan nationalist group Crida per la solidaritat (“Call for Solidarity”) even went so far as to spread pink paint over the port side of the frigate in protest of U.S. actions against Libya.

When the ship finally left port, Newport was still her intended destination. By midday, however, she had been ordered to rendezvous with the rest of her battle group for a strike on Libya. Whereas the prior engagement with the Libyans had strictly been a Navy operation, the U.S. Air Force would also participate this time, launching 18 General Dynamics F-111F Aardvark strike aircraft and four General Dynamics-Grumman EF-111A Raven electronic warfare aircraft from the United Kingdom while 14 Grumman A-6E Intruder attack aircraft and the same number of LTV A-7E Corsair II SAM-suppression bombers would take off from Coral Sea and America. There were eight targets in all, ranging from Benina Airfield to Gaddafi’s own residence.

Given the sensitive nature of this operation coupled with its complexity, coordination between the two forces and the element of surprise would both be absolutely crucial. To that end, the strikes would be launched under the cover of darkness, with Capodanno and her battle group not moving into the Gulf of Sidra until absolutely necessary so as not to alert the Libyans. They even maneuvered to avoid detection by Soviet vessels in the central Mediterranean, recognizing that the Soviets would have no compunction about spoiling the surprise planned for Gaddafi. At midnight local time on 15 April, Operation El Dorado Canyon commenced in earnest, with the Sixth Fleet carriers launching their aircraft to join their USAF brethren in raining down destruction upon their designated targets. Despite facing a steady of stream of anti-aircraft fire, they severely damaged the Libyan air defenses and managed to strike all of their intended targets, causing considerable damage. By 0213, all strike craft were back out over the Gulf of Sidra, save for one F-111F which was ultimately lost at sea along with her crew.

During all of this, Capodanno and the rest the Sixth Fleet maintained their stations in the Gulf of Sidra. While all due preparations had been made for a possible Libyan counter-attack, none was forthcoming either from the air or by sea. Capodanno did not even have to sound General Quarters. Leaving the gulf, she sailed to Siracusa, Italy, for a few days of respite (21–26 April 1986) and then to Gibraltar, Spain (7–8 May) in preparation for her voyage back to Newport. Transiting the Atlantic with the Coral Sea Battle Group, she arrived back in her homeport on 19 May.

For the rest of the year, Capodanno largely alternated between long periods of upkeep and brief stints operating off the coast of the northeastern U.S. Following the end of her post-deployment stand-down, she cruised to nearby Bristol for five days (1–5 July 1986) followed by a dependents’ cruise back to Newport. After a brief period of operations in Narragansett Bay (8–10 July), she spent the next month in port for training, upkeep, and upgrades, including having AN/SQR 18A V(1) and AN/SQR 17A sonar systems installed, as well as a gun port shield ordnance alteration (OrdAlt) performed (14-30 July). Amidst all of this, she also hosted the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) training ship Katori (TV-3501) as part of the Black Ships Festival commemorating of the “Opening to Japan” (25-29 July). When the frigate finally got back underway on 8 August, she sailed to New York for a three-day port visit (9–11 August) and then to Earle to offload her ammunition (11–12 August) in preparation for her upcoming SRA in Boston (13 August–5 November).

During her SRA, Capodanno had new berthing installed on board. While this was being done, her crew kept busy with training and recreational activities, including attending a memorial mass for Father Capodanno in Boston (4 September 1986), holding the First Annual Capodanno Golf Open (12 September), and sponsoring a children’s Halloween Party (26 October). It was not all fun and games, however, as the ship also received a bomb threat on 23 September, a worrisome development in light of her involvement in operations against Libya. Fortunately, nothing came of it and the frigate completed her SRA on 5 November without further incident. She subsequently returned to Newport (6–11 November), followed by visits to Earle (13–14 November) and New York City (14-16 November). The rest of the year was mainly spent in port save for a week of Tail Ship Proficiency training operations (8–15 December).

Capodanno remained in Newport until 18 February 1987, when she got underway for Guantanamo Bay to conduct a month of refresher training (24 February–18 March) and a brief period of operations at the AUTEC Range (21–23 March). After a few days in port at Nassau (24–26 March), she steamed to Roosevelt Roads for port visits (30, 31 March) and NGFS testing at Vieques (30–31 March). With her training complete, she cruised northwards to Charleston, S.C., for both a port visit (5–7 April) and operations in local waters (8–9 April). She finally arrived back in Newport on 12 April after a routine stop in Earle (10 April). For the next four months, she seldom left port due, in part, to the need for her to undergo two separate IMAVs (11 April–1 May, 20 July–7 August) and preparations for the INSURV (11–15 May). When she did leave port, it was for only brief periods of time to conduct local operations, port visits to Halifax, N.S. (5–7 June) and Bristol (4-6 July), and an NGFS test at Bloodsworth Island (16–19 June).

On 28 August 1987, Capodanno began her Atlantic transit to participate in NATO exercises Ocean Safari and Sharem 71. For the next month (28 August–24 September). She operated in the North Atlantic and off the coast of Norway as part of a massive 150 ship fleet engaged in ASW operations and simulated airstrikes. Once these exercises had ended, she cruised to Edinburgh, Scotland, for a two-day port visit (25–26 September) and then returned to Newport on 8 October, where she would remain in port for the rest of the year undergoing numerous inspections.

The year 1988 proved a considerably more harrowing year for Capodanno than the prior one. Just over one week into the new year (8 January), she set a course for Puerto Rico to participate in FleetEx 1-88. Upon her return to Newport on 30 January, she began a month of intensive preparations for her upcoming deployment to the Mediterranean, which included undergoing an aviation readiness exam (ARE).

Getting underway on 29 February 1988, she arrived in the western Mediterranean on 13 March and immediately made for Cagliari (15 March). In the four days that followed, the ship engaged in ASW line operations before sailing into Palermo, Sicily, for an eight-day port visit (22–29 March). At the end of this, she immediately cruised to Naples for an even lengthier stay in port (31 March–16 April), during which she received a performance monitoring team visit (7–8 April).

While Capodanno was moored in Naples, the local USO club decided to hold a talent show on 14 April 1988 for her crew and that of Paul (FF-1080). Approximately 40 sailors attended what was supposed to a night of fun and relaxation prior to some of the most intensive weeks of the deployment. As the showed neared its conclusion, however, a car bomb exploded outside of the club, wounding 18 people and killing five, including Petty Officer 3rd Class Angela Santos, who was volunteering for the USO at the time. Three of Capodanno’s sailors (ET3 Craig L. Trent, FCCS Charles F. Roberts, and ET3 Stanley Lawson, Jr.) were also wounded in the blast. Investigators eventually identified Japanese Red Army member Junzo Okudaira as the perpetrator.

Although the Japanese Red Army was, as the name suggests, comprised of Japanese far-left militants seeking to incite a Marxist revolution in their homeland, it had actually been founded in Lebanon in 1971. Establishing links to several terrorist organizations, it committed a number of acts of terror during the 1970s and 80s, most notably, massacring 26 people at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv in May 1972. Just a year prior to the USO club bombing, they had launched mortar shells at the U.S. and British embassies in Rome. A statement released by the group (using the name, “Brigades of the Holy War”) claimed that the Naples attack was retaliation for the attack on Libya two years prior. It was later found that the group was indeed linked to the Gaddafi regime. Whether or not they were aware that Capodanno had participated in the air strikes is unknown, but regardless, this incident was a sobering reminder that Soviet warships were not the only the threat to Navy sailors during this period.