Atik (AK-101)

1942

A double star in the constellation Perseus.

(AK-101: displacement 6,610; 1ength 382'2"; beam 46'1"; draft 21'6"; speed 9 knots; complement 141; armament 4 4-inch, 4 .50-caliber machine guns, 4 .30-caliber Lewis machine guns, 6 depth charge projectors)

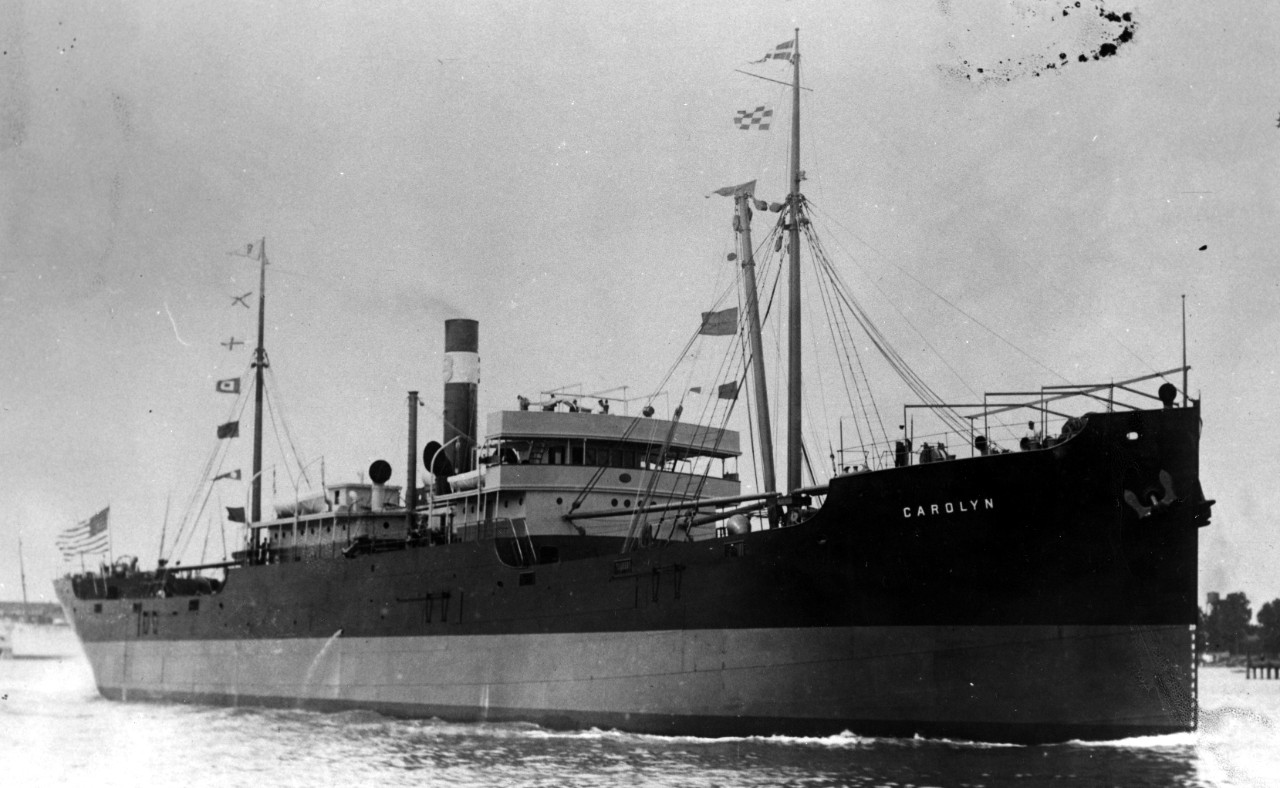

Carolyn, a steel-hulled, single-screw steamer, was laid down on 15 March 1912 at Newport News, Va., by the Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co., for the A. H. Bull Steamship Lines; launched on 3 July 1912; sponsored by Miss Carolyn Bull (for whom the ship was probably named), a granddaughter of the shipping line's owner, Archibald Hilton Bull (1847-1920).

Delivered on 20 July 1912, Carolyn carried freight and passengers between the West Indies and ports on the eastern seaboard of the U.S. for the next 30 years. During World War I, she received a main battery of a 3-inch and a 5-inch gun, and a Navy armed guard served in the ship from 28 June 1917 to 11 November 1918. During that time, too, the Navy gave her the identification number (Id. No.) 1608, but did not take her over for naval service.

Carolyn pursued her prosaic calling under the house flag of the Bull Line into 1942. By 12 January 1942, the British Admiralty’s intelligence community had noted a “heavy concentration” of U-boats off the “North American seaboard from New York to Cape Race” and passed along that fact to the U.S. Navy.

That same day [12 January 1942], the German submarine U-123, Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen commanding, torpedoed and sank the unescorted British steamship Cyclops, inaugurating Operation Paukenschlag (literally, “roll on the kettledrums”) and commencing a “blitz” against coastal shipping between New York Harbor and the Outer Banks.

The crisis begat a new, imaginative, and daring program. Given the highly secret nature of the project, mystery shrouds its inception. It appears that President Franklin D. Roosevelt, well-known for his affinity for things novel and naval, desired that the Navy establish a “Q-ship” program similar to that which had been used by the British with some success in the World War.

The War Shipping Administration (WSA) acquired Carolyn from the Bull Line under a bare boat charter at Portsmouth, N.H., at 3:30 p.m. on 12 February 1942. Her acquisition by the Navy followed within two weeks of the dispatch from the Chief of Naval Operations dated 31 January 1942 which had stated his desire that Evelyn (Carolyn’s sister ship) and Carolyn “be given a preliminary conversion to AK in the shortest possible time.” A letter from the Chief of the Bureau of Ships elaborated on the “shortest possible time,” when it stated on 12 February that the conversion and outfitting of the vessels was desired “by 1 March 1942.”

As could be expected, the process of converting two venerable “tramp” steamers into improvised men-of-war was by no means a complete one; but, over the next few weeks, the two former tramps were given their main and secondary batteries, sound gear, and depth charge projectors. Outwardly, they appeared to be cargo ships. Carolyn became Atik, and was given a cargo ship identification number, AK-101; Evelyn became Asterion (AK-100).

Atik (AK-101) was placed in commission at 1645 on 5 March 1942 at the Portsmouth (N.H.) Navy Yard, Lt. Cmdr. Harry L. Hicks in command. Following fitting out and brief sea trials, she and Asterion got underway on 23 March 1942. Atik sailed short four members of her crew: she listed two men in the U.S. Naval Hospital, Portsmouth Navy Yard, and two sailors who had failed to return to the ship, absent over leave, one on 15 March and the other on the 16th. Soon after leaving port, Atik and Asterion went their separate ways.

At the outset, all connected with the program apparently harbored the view that neither ship “was expected to last longer than a month after commencement of [her] assigned duty.” Atik’s holds were packed with pulpwood, a somewhat mercurial material. If dry, “an explosive condition might well develop” and, if wet, “rot, with resultant fire might well take place.” Despite these disadvantages, pulpwood was selected as the best obtainable material to assure “floatability.”

Atik’s mission was to lure an unsuspecting U-boat into making a torpedo attack. According to the projected scenario, the submarine, having deemed the venerable tramp unworthy of the expenditure of more torpedoes, would surface to sink the crippled foe with gunfire. The plan presupposed a “backup” that was to come to the rescue whenever a Q-ship ran into difficulties. In March 1942, though, no such “safety net” existed. “The commanding officers of the two ships [Atik and Asterion] were told [that] they could expect little help if they got into trouble as the situation was critical. Every available combatant ship and plane were [sic] being employed to the maximum for convoy and patrol duties.”

In the gathering darkness, three days after Atik had cleared Portsmouth, however, she attracted the attention of U-123, on her second war patrol off the eastern seaboard. The U-boat, on the surface, began stalking Atik at 2200, and at 0037 on 27 March 1942 fired one torpedo at a range of 700 yards that struck the ship on her port side, under the bridge. Fire broke out immediately, and the ship began to assume a slight list, the crippled “freighter” sending out a terse SOS: “S.S. Carolyn, torpedo attack, burning forward, not bad.” As U-123 proceeded around under her victim’s stern, Kapitänleutnant Hardegen duly noted one boat being lowered on the starboard side and men abandoning ship.

After U-123 turned to starboard, “Carolyn” gathered steerageway. She steered a course paralleling the enemy’s by turning to starboard as well, then dropped her concealment, opening fire from her main and secondary batteries. The first 4-inch shell splashed short of the U-boat, as she made off presenting a small target; the shots that followed were off in deflection. Heavy .50-caliber machine gun fire, though, ricocheted around the U-boat’s decks as she bent on speed to escape the trap into which Hardegen “like a callow beginner [his own words]” had fallen. One bullet mortally wounded Fähnrich zur See Rudi Holzer, on U-123’s bridge.

Gradually, the U-boat pulled out of range behind the cover of the smoke screen emitted by her straining diesels, and her captain assessed the damage. As Hardegen later recorded, “We had been incredibly lucky.” U-123 submerged and again approached her adversary. At 0229, the U-boat loosed a torpedo into Atik’s machinery spaces. Satisfied that that blow would prove to be the coup de grace, U-123 stood off to await developments as Atik settled by the bow, her single screw now out of the water.

Once again, Atik’s men could be seen embarking in her boats. U-123 surfaced at 0327, to finish off the feisty Q-ship. Suddenly, at 0350, a cataclysmic explosion blew Atik to pieces. Ten minutes later, U-123 buried her only casualty, Fähnrich zur See Holzer, who had died of his wounds. Atik’s entire crew perished, either in the blast that destroyed the ship or during the severe gale that lashed the area soon after the brave ship disintegrated.

The next morning, a USAAF bomber dispatched to Atik’s last reported position found nothing. The destroyer Noa (DD-343) and the tug Sagamore (AT-20) steamed toward the area as well. Heavy seas forced Sagamore to return to port, but Noa remained in the vicinity and ultimately sighted wreckage from Atik.

Asterion, too, had heard her sister ship’s SOS and set course for the scene of the engagement, Lt. Cmdr. Glenn W. Legwen, Jr., her commanding officer (and a Naval Academy classmate of Atik’s Lt. Cmdr. Hicks) deeming his orders “sufficiently broad to proceed immediately to her [Atik’s] assistance.” Asterion encountered casualties to her steering gear, however, and only continued the search for 24 hours before being forced to put into Hampton Roads for repairs.

On 9 April 1942, Radio Berlin reported that a U-boat had sunk an adversary after a “bitter battle” but did not elaborate. “For administrative purposes,” Rear Adm. Russell Willson, wrote in a memorandum for the Chief of Naval Personnel on 2 July 1942, “the subject ship [Atik] should be considered to have been lost on 27 March, 1942.” He added: “Aside from such notifications as have already been made to dependents, no further publicity will be given to the loss of this ship.” Not until after the war did translated Kriegsmarine records shed light on what had become of Atik.

Atik received one battle star for her World War II service, for her battle with U-123.

Robert J. Cressman

21 March 2017