Compiled by Brent Hunt, Naval History and Heritage Command’s Communication and Outreach Division

Today in Naval History

On Nov. 1, 1777, during the American Revolution, Continental ship Ranger, commanded by Capt. John Paul Jones, hoisted its sails for France, carrying word of British Gen. John Burgoyne’s surrender at the New York battlefield of Saratoga. Ranger arrived at the French port of Nantes a month later, where Jones initially sold the prizes his crew had captured on the voyage over the Atlantic—Mary and George—and delivered the news of the unprecedented American victory to his dear friend, Founding Father Benjamin Franklin. At the time, Franklin held a diplomatic position as a representative of the colonies to the French government. The victory at Saratoga helped solidify France’s support for the American colonies’ quest for independence. France, based on the news and Franklin’s political efforts, joined the American cause in 1778 (Spain joined about a year later and the Netherlands in 1780). French naval superiority ultimately forced the British surrender at Yorktown, which ended the fighting and gave birth to a new American nation.

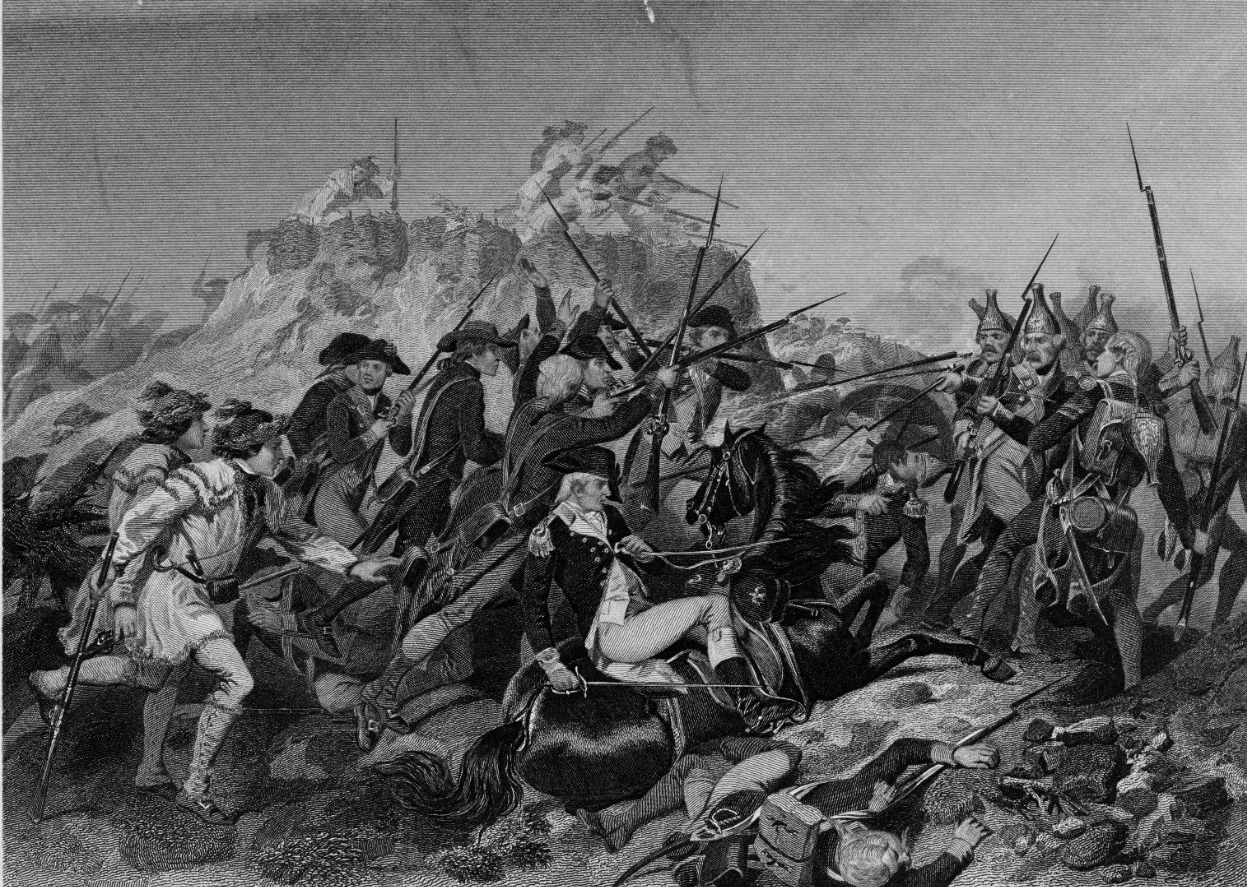

Leading up to the victory at Saratoga, Britain’s strategy had been to drive a wedge between New England and the other colonies. Burgoyne’s troops were to march south from Canada and join forces with Gen. William Howe on the Hudson. However, Howe assumed Burgoyne’s army was strong enough to operate on its own and departed New York in the summer, taking his army by sea to the northern point of the Chesapeake Bay. Once ashore, Howe defeated Gen. George Washington’s troops at Brandywine Creek, Delaware, in September and moved west toward Philadelphia, which at the time was the American capital. The Continental Congress fled to York, Pennsylvania, while Washington’s troops went into winter quarters at Valley Forge. In the north, the situation was more difficult for the British. Burgoyne was to move south to Albany with a force of about 9,000, and a smaller contingent was to converge on the city through the Mohawk Valley. Burgoyne took American-held Fort Ticonderoga easily, and instead of using Lake George for transit, decided to go southward by foot. Slowed by the rugged terrain, Burgoyne sent a force of Germans, who were part of his army, to Vermont to collect horses. While there, the German contingent was nearly wiped out by New Englanders. Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Barry St. Leger, under Burgoyne, overwhelmed Fort Schuyler (now Rome, New York) and ambushed a column of American militia at Oriskany, but he retreated as an American force under Benedict Arnold approached. Burgoyne ultimately reached the Hudson, but the Americans, under Arnold, engaged his troops at Freeman’s Farm on Sept. 19, 1777. On Oct. 7, Arnold’s troops decisively defeated Burgoyne’s army at Bemis Heights. Ten days later, Burgoyne was forced to surrender at Saratoga.

After the surrender at Saratoga and France’s entry into the war, the situation at sea dramatically changed. The British navy was unable to effectively blockade American ports, and its vessels suffered from their long periods underway. Not only did England have to face hostile privateers from the colonies, France, and Spain—as well as raids from the likes of John Paul Jones—they also feared invasion. The combined fleets of France and Spain gained superiority in the English Channel, and a 50,000-man French army was in wait to board the vessels. Fortunately for the British, bad weather and sickness ultimately halted the invasion. Despite losing the English Channel, the British navy still reigned superior on the North American seaboard for most of 1779 and 1780. However, by 1781, British merchants were clamoring for an end to hostilities due to high insurance rates and loss of revenue. Although the 1781 Battle of Yorktown was the final clash of the American Revolution, the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 formally ended the war.

Happy Birthday, U.S. Marines!

On Nov. 10, 1775, the second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and voted to raise two battalions of Marines for service as landing forces, establishing today’s U.S. Marine Corps. Serving on land and at sea, these first Marines distinguished themselves in a number of important operations that included, under the command of Capt. Samuel Nicholas, the first amphibious assault that took place in the Bahamas in March 1776. Nicholas was the first commissioned officer in the Continental Marines and remained the senior Marine throughout the American Revolution. After the war, the Continental Navy’s ships were sold, and the Marines were discharged.

After the U.S. Navy was reestablished in 1794, the Marines were subsequently reestablished on July 11, 1798. During the Quasi-War with France, Marines landed on Santo Domingo and, between 1801 and 1805, took part in multiple operations against the Barbary pirates along the “Shores of Tripoli.” During the War of 1812, Marines took part in the defense of Washington at Bladensburg, Maryland, and fought alongside Andrew Jackson in the defeat of the British at New Orleans. During the Mexican-American War, Marines seized enemy seaports on both the Gulf and Pacific coasts. A battalion of Marines joined Army Gen. Winfield Scott at Pueblo and fought all the way to the “Halls of Montezuma” in Mexico City. Marines continued to perform with valor during the Spanish-American War on operations in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

In World War I, the Marine Corps distinguished itself on the battlefields of France as the 4th Marine Brigade earned the title “Devil Dogs” for their actions during the pivotal 1918 Battle of Belleau Wood and during the final Meuse-Argonne offensive. Marine aviation also played a significant role in the war with bomber missions over France and Belgium. More than 30,000 Marines served during the war and roughly one-third of them were either killed or wounded.

Prior to World War II, the Marines began to develop doctrine, equipment, and organization for amphibious landings. This effort proved successful first on Guadalcanal, then on Bougainville, Tarawa, New Britain, Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Saipan, Guam, Tinian, Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. By the end of the war, the Marine Corps had grown to include six divisions, five air wings, and supporting troops. During World War II, 87,000 Marines were either killed or wounded. Eighty-two Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor.

In September 1950, Marines once again answered the nation’s call when North Korea invaded South Korea, launching the Korean War. They participated in the landings at Inchon, the recapture of Seoul, and the battle of Chosin Reservoir, which marked the beginning of millions of Chinese soldiers entering the war. After years of offensives, counteroffensives, endless trench warfare, and occupation duty, the last Marines were withdrawn in March 1955. More than 25,000 of them were killed or wounded during the conflict.

The landing of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade at Da Nang in 1965 (the first U.S. combat troops in Vietnam) marked the beginning of large-scale American involvement in the Vietnam War. By the summer of 1968, after the enemy Tet Offensive, Marine strength peaked to approximately 85,000 boots on the ground. The Marines began to withdrawal in 1969, when the South Vietnamese military began to play a larger role in the war. The last Marine ground forces left Vietnam in June 1971. As in previous conflicts, the Marines paid a heavy price. More than 13,000 were killed and another 88,000 wounded. In the spring of 1975, Marines participated in the evacuation of embassy staffs, American citizens, and refugees in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, after the fall of Saigon.

The mid-1970s saw the Marine Corps assume an increasingly significant role in defending NATO's northern flank as amphibious units of the 2nd Marine Division participated in exercises throughout northern Europe. The 1980s brought an increasing number of terrorist attacks on U.S. embassies around the world. Marines, under the direction of the State Department, continued to serve in their role as embassy guards with distinction. In August 1982, Marine units landed on Lebanon as part of the multinational peacekeeping force. For the next 19 months, Marines participated in various operations in an attempt to keep the peace and stabilize the country. Tragedy struck on Oct. 23, 1983, when two truck bombs struck separate buildings housing U.S. Marines and French forces at the Beirut Airport, killing nearly 300 American and French servicemembers. One of the trucks rammed through the gate at the entrance of the building housing 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, and the driver detonated the improvised bomb, killing 220 U.S. Marines, 18 Sailors, and three Army Soldiers. More than 100 were also injured in the attack. Later that month, Marines took part in a short-notice operation in Grenada. As the 1980s came to a close, Marines were summoned to Central America to respond to government instability. Operation Just Cause was launched in Panama in December 1989 to protect American lives and restore the democratic process.

The next decade proved to be another demanding time in U.S. Marine Corps history. Between August 1990 and January 1991, 92,000 Marines deployed to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Desert Shield/Storm in response to the Iraqi army’s invasion of Kuwait. The main attack came on Feb. 24 when the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions breached Iraqi defense lines and stormed into Kuwait. By the morning of Feb. 28, 100 hours after the ground war began, almost the entire Iraqi army in the Kuwaiti theater of operations had been encircled, with 4,000 tanks destroyed and 42 divisions destroyed or rendered ineffective. Marines rounded out the decade with a humanitarian mission in Somalia, peacekeeping missions in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo, the restoration of democracy in Haiti, and the evacuation of American citizens in several African nations due to civil unrest.

In more recent events, the Marines played a significant role in the Global War on Terrorism in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on New York City and Washington, DC. Marines deployed to the Arabian Sea, and in November, set up a forward operating base in southern Afghanistan in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. Marines expanded their role in anti-terrorism activities with deployments to the Arabian Gulf, the Horn of Africa, and the Philippines. In 2003, the largest deployment of Marines since the Persian Gulf War occurred when 76,000 Marines deployed to the Central Command area of operations for combat operations in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Today, the Marine Corps continues to be ready to answer the nation’s call just as those who so valiantly fought and died at Belleau Wood, Iwo Jima, the Chosin Reservoir, and Fallujah. Happy Birthday, U.S. Marines!

Navy Nursing Pioneer—Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee

On Nov. 11, 1920, Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee, superintendent of the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps, became the first woman to be awarded the Navy Cross while still alive for her service during World War I. Three other nurses were posthumously awarded the Navy Cross for their service during the “Great War”—Lillian M. Murphy, Edna E. Place, and Marie L. Hidell, all victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Named in her honor, USS Higbee (DD-806) was commissioned in 1945 and was the first U.S. Navy combat ship to bear the name of a female servicemember that served in the U.S. Navy. USS Lenah Sutcliffe Higbee (DDG-123), an Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer under construction, is also named for the pioneer nurse.

Higbee, born on May 18, 1874, in the Canadian province of New Brunswick, completed her formal nursing training at the New York Postgraduate Hospital in 1899, and that same year, married retired U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Col. John Henley Higbee. Initially, Higbee worked in private practice, but following her husband’s untimely death in April 1908, she advanced her nursing career by completing postgraduate work at Fordham Hospital in New York City. On May 13, 1908, Congress passed legislation establishing the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps. The legislation required that candidates be between the ages of 22 and 44 and be unmarried. Applicants had to be graduates of a general hospital training school with at least a two- year program and have clinical experience in a hospital. All nurses were subject to an examination of their professional, moral, mental, and physical fitness.

Shortly thereafter, the 36-year-old widow Higbee, who previously worked as a U.S. Army contract nurse aboard hospital ship Relief during the Spanish-American War, joined 19 other women to form the first group of Navy nurses known as the “Sacred Twenty.” On Oct. 1, 1908, Higbee was appointed a Navy nurse and was ordered to duty at the U.S. Naval Hospital in Washington, DC. About a year later, she became the chief nurse at the Norfolk Naval Hospital, Virginia, and two years later, was appointed superintendent of the Navy’s Nurse Corps. She was the second to hold the position. Esther Voorhees Hasson was the first superintendent and had also served alongside Higbee as a U.S. Army contract nurse during the Spanish-American War. Higbee led the U.S. Navy Nurse Corps during the war and, most notably, during the deadly Spanish influenza pandemic. It is estimated that 500 million people were infected with the virus, roughly one-third of the world’s population. The flu killed more than 50 million worldwide. Between the fall of 1918 and the spring of 1919, 5,027 Navy personnel died as a result of the pandemic, more deaths than at Pearl Harbor, Guadalcanal, or Okinawa.

In addition to leading the Navy Nurse Corps during one of the most challenging times in world history, Higbee, as superintendent, advocated for the health care of dependent military families, formalized Navy nursing uniforms, and grew the corps from a meager 160 to more than 1,300 nurses. Higbee retired from the Navy in 1922 and passed away in Winter Park, Florida, on Jan. 10, 1941. She is buried next to her husband at Arlington National Cemetery.

President Doubles Carrier Battle Groups in Persian Gulf

On Nov. 8, 1990, former World War II naval aviator President George H.W. Bush announced the executive decision to double the number of aircraft carrier battle groups deployed to the Persian Gulf in support of Operation Desert Shield. By Jan. 15, 1991, USS Ranger (CV-61), USS America (CV-66), and USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) were to join USS Midway (CV-41), USS Saratoga (CV-60), and USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67). The move was in response to Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s brutal invasion of his country’s southern neighbor—Kuwait—in August 1990. The buildup was also in anticipation of possible further aggression geared toward another sovereign nation in the region, Saudi Arabia.

In the 1980s, the United States had supplied Iraq with military aid during its eight-year war with Iran, giving the country one of the world’s largest armies in the world at that time. Now, in addition to the aggression toward Kuwait, the Iraqi military posed a threat to Saudi Arabia, another major exporter of oil. If Saudi Arabia did fall, Iraq would control roughly one fifth of the world’s oil supply. Following his invasion of Kuwait, and despite numerous United Nations (UN) resolutions and severe economic sanctions, Hussein refused to withdraw his forces.

On paper, the Iraqi military appeared formidable. Hussein’s army had about 950,000 personnel, 5,500 main battle tanks, 10,000 additional armored vehicles, and 4,000 artillery pieces. The Iraqi air force consisted of about 40,000 personnel with up to 700 aircraft. In addition, the Iraqi military had had extensive combat experience during the Iraq-Iran War. It was also believed that Iraqi troops had used chemical or biological weapons during some of their operations. After the invasion of Kuwait, the U.S. military carried out the largest overseas deployment since World War II. By mid-November, the United States had more than 240,000 troops in the Gulf, and another 200,000 were on the way. England contributed about 25,000 troops, Egypt 20,000, and France 5,500. Other countries, including Canada, Syria, Bangladesh, and Morocco, also contributed. On Nov. 29, 1990, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 678, sanctioning the use of force if the Iraqis had not withdrawn from Kuwait by Jan. 15, 1991. The coalition began combat operations against Iraq shortly thereafter.

On Jan. 17, 1991, Desert Shield transitioned to Desert Storm, and the following day, allied air assets began bombardment operations that saw more than 18,000 air deployment missions, 116,000 combat air sorties, and the deployment of 88,500 tons of bombs. After the unprecedented, six-week aerial campaign, ground forces began their assault that lasted a mere 100 hours before the Iraqi army was expelled and Kuwait was liberated. During the assault, Iraq desperately tried to split the coalition by launching Scud missiles at Israel, but the deflection did not work and Israel refrained from retaliatory attacks.

Desert Storm was the United States’ first use of the Patriot missile system in combat, and it was also the first time the U.S. military used its stealth and space capabilities against a modern air defense. In addition, it was the first major international crisis of the post–Cold War world. The Navy’s role during Desert Shield/Storm was clear. Forward deployed naval forces provided protection for the early introduction of land-based ground and air forces, and may have deterred further aggression by Iraq.