Gamble at Los Negros: The Admiralty Islands Campaign

29 February 1944

Shortly after the United States and Imperial Japan assumed their roles as belligerents in World War II, the Japanese began a rapid conquest of the various Pacific islands held by the Allied powers. Among these were the Bismarcks, the Northern Solomons, and Papua New Guinea. In January 1942, Japanese forces overwhelmed and seized Rabaul, the capital township of the Territory of New Guinea, which thereafter provided Japan with a formidable base of operations for its air and naval facilities in the region. In addition to a sizeable garrison of approximately 100,000 Japanese soldiers, a ring of occupied islands around New Guinea provided for Rabaul’s defense. The broad campaign undertaken by Allied forces to drive the Japanese out of the area and deprive them of their Rabaul base consisted of a number of operations in the surrounding island chains, which fell under the overall code name of Operation Cartwheel (1943–44).1

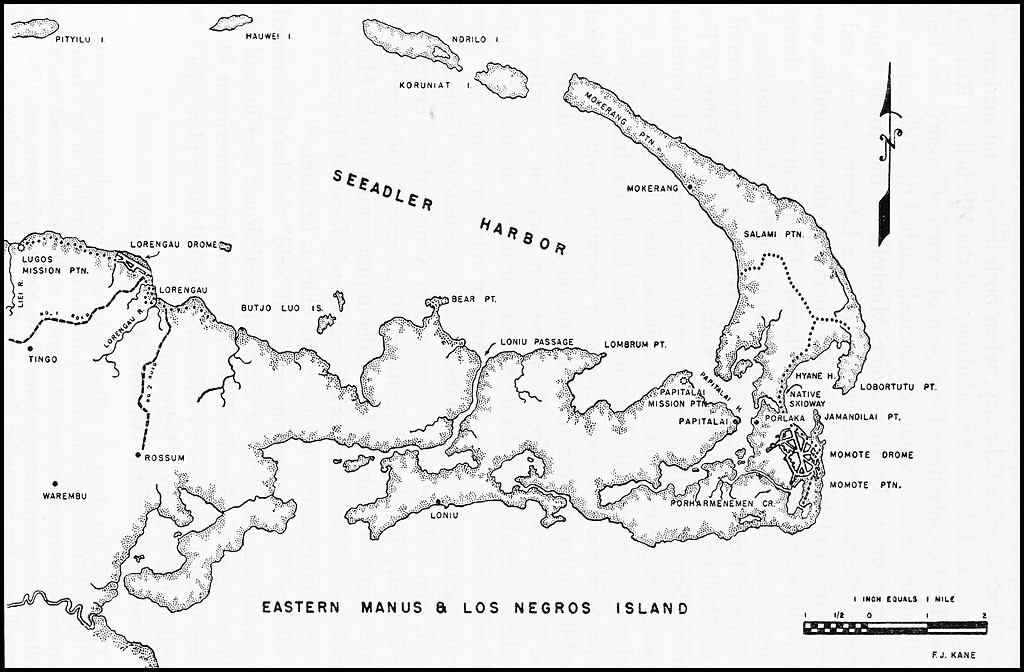

One of the key sub-operations of Cartwheel was Operation Brewer, which began in February 1944 and consisted of a series of amphibious actions that sought to capture the Admiralty Islands. Brewer’s success proved instrumental in both further isolating Rabaul, as well as providing Allied forces with new operating bases in the region.2 The Admiralty Islands group consists of 160 small islands, the chief of which are Manus and Los Negros, located 200 miles northeast of mainland New Guinea and approximately 360 miles west of Rabaul. The primary prizes offered by the two islands were the Momote airfield and Seeadler Harbor, the latter of which was one of the largest in the region. Seeadler is formed by the ellipse of Manus and the adjoining shoreline of Los Negros. The harbor is one and a half miles wide and approximately 100 feet deep. Due to its depth and the protection afforded by its natural formation, it can accommodate a large fleet.3

____________

1 John Miller, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, United States Army in World War II: The War in the Pacific (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, U.S. Department of the Army: 1959), 1–6.

2 Ibid., 316–17.

3 Michael Walling, Bloodstained Sands: U.S. Amphibious Operations in World War II, (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2017), 205–207.

At the helm of Cartwheel was General Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of Allied Forces in the South West Pacific. In undertaking Brewer, MacArthur worked closely with the U.S. Navy’s Seventh Fleet, under the command of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid.4 As the two contemplated the conquest of the Admiralties, a favorable air reconnaissance report indicated that Los Negros might be deserted, and, on 26 February, the order was given for a reconnaissance force to land on the island and either withdraw or advance as deemed necessary.In either case, MacArthur and Kinkaid were going to be on hand to make the determination.5 As Samuel Eliot Morison noted, “the whole operation was a gamble.”6

In the early morning hours of 29 February 1944, Task Group (TG) 74 and Task Force (TF) 76.1, under the operational command of Rear Admiral William M. Fechteler, arrived in the vicinity of Los Negros. TG 74 consisted of the light cruisers Phoenix (CL-46) and Nashville (CL-43). accompanied by the destroyers Daly (DD-519), Beale (DD-471), Hutchins (DD-476), and Bache (DD-470). Phoenix acted as the flagship of the group, and MacArthur and Kinkaid had embarked on her several days prior to the operation. The task group’s primary mission was to bombard the shoreline in advance of the landings. Phoenix, Daly, and Hutchins were tasked with targeting the Momote airdrome while Nashville, Beale, and Bache attacked the Lorengau area.7

While TG 74 had the primary mission of shelling Japanese shore emplacements, TF 76.1 was to be employed in landing troops and providing fire support. The task force included nine destroyers: Reid (DD-369), the flagship on which Rear Admiral Fechteler was embarked; Bush (DD-529); Welles (DD-628); Flusser (DD-368); Mahan (DD-364); Drayton (DD-366); Smith (DD-378); Stevenson (DD-645); and Stockton (DD-646). In addition to these there were three high-speed transports: Brooks (APD-10), Humphreys (APD-12), and Sands (APD-13). Troops were embarked on board the destroyers, as well as the transports, and between them the ships carried 1,026 soldiers.8 The embarked troops, under the command of Brigadier General William C. Chase, primarily included soldiers of the 5th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, but also included a contingent of Australians assigned to the Australia New Guinea Administrative Unit.

____________

4 Miller, Cartwheel, 5–6.

5 Charles Willoughby, The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, Volume I, Reports of General MacArthur (Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History Reports of General MacArthur, 1966) 137.

6 Samuel Eliot Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier: 22 July 1942–1 May 1944, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1950), 436.

7 (Declassified) War Diary, Commander of U.S.S. Phoenix (CL-46), “Action Report: Los Negros, Admiralties Group” 29 February 1944, National Archives, Washington DC.

8 Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 436–37.

Despite the fact that air reconnaissance had indicated that the island might be evacuated, there was ample evidence to the contrary. Reports from the Allied Intelligence Bureau indicated that according to local civilians there might be at least 2,450 Japanese troops still on the island.9 In the event that the Japanese were still there, the decision was made to land at Hyane Harbor on the east side of Los Negros. Although not as accommodating as Seeadler Harbor, the Allies believed that it would be less heavily defended.10 The bombardment of the shoreline began at 0740 with Phoenix firing the first salvo, followed by the others in her task group. All doubts as to the presence of the Japanese were dispelled when shore batteries began exchanging fire with the American warships. In addition to the naval bombardment, North American B-25 Mitchell bombers from the Fifth Army Air Force strafed targets all along the island; unfortunately, the air support was inhibited by the day’s increasingly overcast weather.11

The first wave of troops proceeded to the beach at 0755 and, at 0814, the order was given to cease the bombardment as landing craft arrived at their destinations. The APDs lowered LCPRs (landing craft, personnel, ramped), each holding 37 men, and the soldiers stepped onto the beach at approximately 0817.12 At 0826, the first wave of troops came under fire from shore-based machine guns, to which the destroyers replied in force with their armaments. Amid the exchange the second assault wave was temporarily forced to reverse course until the destroyers had silenced the machine-gun nests.13 Troops continued to be ferried ashore over the next four hours and a heavy rain set in, which, fortunately for the Americans, reduced the visibility of the Japanese defenders.14

____________

9 Willoughby, The Campaigns, 137–38.

10 Walling, Bloodstained Sands, 205–206.

11 (Declassified) War Diary of U.S.S. Phoenix, “Action Report: Los Negros.”

12 (Declassified) War Diary, Commander of U.S.S. Brooks (APD-10), “Action Report: Los Negros, Admiralties Group” 29 February 1944, National Archives, Washington DC.

13 (Declassified) War Diary, Commander of U.S.S. Reid (DD-369), “Action Report: Los Negros, Admiralties Group” 29 February 1944, National Archives, Washington DC.

14 William C. Frierson, The Admiralties: Operations of the 1st Cavalry Division, 29 February–18 May 1944, American Forces in Action, (Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 1990 [1946]), 29.

Japanese forces on the island were taken by complete tactical surprise by the landing at Hyane, as they had suspected that if a landing were to occur it would be at Seeadler.15 The Allied soldiers eventually broke out from the beach and overran the nearby Momote airstrip, running, at least initially, into only sporadic opposition.16 The 4,000-foot-long airfield had been badly damaged by bombing, but it was eventually revitalized by the Seabees of Mobile Construction Battalion 40, who began work on it on a few days later. It is worthy of note that they did so while the area was still an active battlefield, a daring feat for which they received the Presidential Unit Citation.17 As for the initial action—with the day essentially won, MacArthur and Kinkaid briefly came ashore at 1600 and surveyed the conquered beachhead; just over an hour later at 1729 the majority of Rear Admiral Fechteler’s force departed the area. The following day, a second wave of follow-up forces arrived in addition to three tons of supplies dropped by the aircraft of the 375th Troop Carrier Group.18

On land, the fight for Los Negros continued on through the remainder of the month, culminating in a last stand by 50 surviving Japanese soldiers in the Papitalai Hills on 24 March 1944.19 Los Negros was only the first of multiple amphibious actions that made up Operation Brewer—or the Admiralties Campaign as it is also known—with subsequent bombardments and landings at Manus, Hauwei, Ndrilo, Pityiluu, Koruniat and finally Rambutyo on 3 April.20 Following the landings, the fighting on land continued, and it was not until 18 May that Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, the commander of the U.S. Sixth Army, officially declared the struggle for the Admiralty Islands to be at an end.21 The success of the operation resulted in the construction of Lombrum Naval Base (the present-day Papua New Guinea Defence Force Base Lombrum) and the acquisition of the Momote airfield, which greatly benefited Allied forces.22 In the end, the gamble had paid off and the Allied victory in the Admiralties helped further the isolation and eventual defeat of Japanese forces at Rabaul.

—Jeremiah D. Foster, NHHC Histories and Archives Division, January 2019

____________

15 Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 436–37.

16 Frierson, The Admiralties, 31.

17 U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: A History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, (1940–1946, Volume 2), 295–96.

18 Frierson, The Admiralties, 36.

19 Ibid., 36.

20 Walter Krueger, “Report on the Brewer Operation,” Series 4, Box 3/14, Walter Kruger Papers, Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, Texas A&M University, 2 August 1944.

21 Ibid.

22 U.S. Navy Seabee Museum, Building the Navy's Bases, 295.