The Scuttling of the German High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow

21 June 1919

Abject military defeat, revolutionary insurrection, and a frustrated peace—this was the context in which German Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter ordered his men to scuttle the German High Seas Fleet, interned at Scapa Flow, Scotland, on 21 June 1919.

In issuing these orders, von Reuter violated the terms of the Armistice. Article XXXI of that legal document, which German military authorities signed back in November 1918, and therefore promised to obey, stated clearly that the Germans were not to destroy a single ship. A century later, it is still difficult to make sense of why, exactly, von Reuter took matters into his own hands in this way. Attention to the greater context, however—on the ground in Germany, at the negotiating tables in and around Paris, and in Scapa Flow—reveals the political motivations and meaning of this spectacular act of defiance.

By the end of summer 1918, the German Empire had lost World War I in a swift defeat at the hands of Allied forces on the western front. In early November, the German war effort collapsed, with disorderly retreats, widespread mutinies, and a revolution that overthrew the Kaiser and established two rival republics. The country descended into what amounted to a civil war while the Germans’ foes in the west and the east looked on to see what would happen: a Bolshevik coup, as had occurred recently in Russia, or perhaps a liberal-democratic revolution, as President Woodrow Wilson hoped. Meanwhile, in the first half of 1919, Wilson found himself in difficult negotiations with the other victors to produce a document that could officially end World War I.

The Armistice and the Surrender of the Fleet

By signing the Armistice on 11 November 1918, the German government agreed with Article XXXI, which forbade the “destruction of ships or of materials . . . before evacuation, surrender, or restoration.” The agreement also stipulated the terms of the surrender of surface ships, with Articles XXII and XXIII leaving some vessels in Germany to be dealt with later and assigning others to a foreign port, as yet undetermined, within 14 days. Subsequently, the victors agreed upon Scapa Flow as the place of internment.

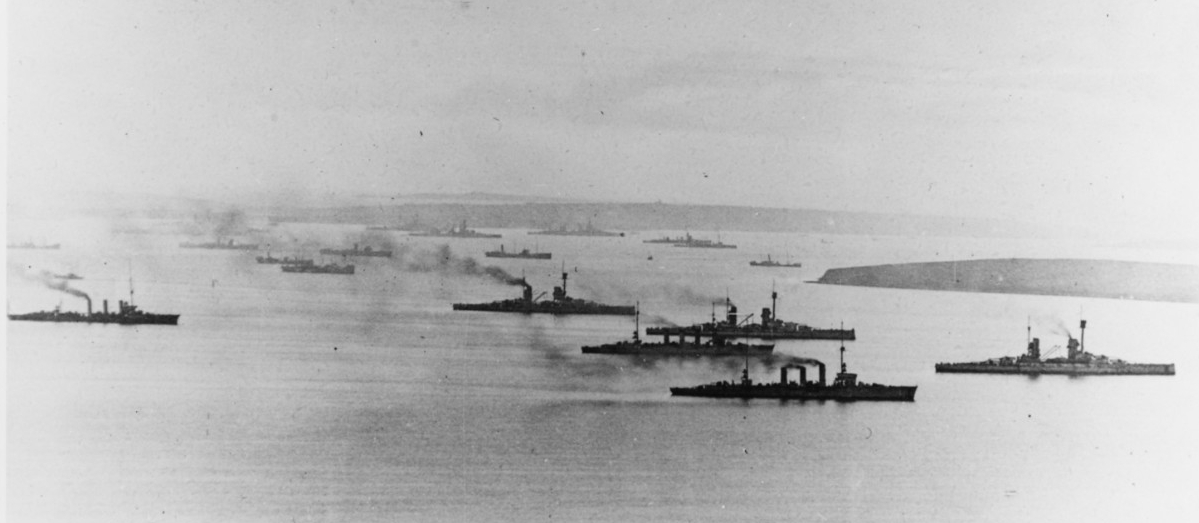

Vessels, including submarines, began to leave Germany as early as 18 November 1918, one week after the Armistice agreement. By 21 November, von Reuter and the bulk of Germany’s seaworthy surface fleet lay waiting near the Firth of Forth for further orders. There to meet the German flotilla was the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, as well as a U.S. squadron. The war had not yet ended, after all. It was merely suspended, as the Germans, having sued for peace and agreed to the terms, still needed to sign a treaty that would formally end hostilities.

In small groups on 25, 26, and 27 November, Germany’s 11 battleships, 5 battle cruisers, 8 light cruisers, and 50 destroyers (Torpedoboote) assumed their assigned positions in the bay. Their internment had begun.

Internment

It was not an indefinite internment. Eventually, once the German government had signed the formal treaty of peace, the ships would be confiscated and their crews sent home. In the meantime, the vessels had to be disarmed.

British authorities oversaw the removal of the breechblocks, which immobilized the guns. They also insisted on stripping all ships of wireless communications capabilities. British authorities subsequently restricted and regulated all routes of communication, especially those emanating from Friedrich der Grosse, von Reuter’s ship. Under certain well-defined circumstances, high-ranking German officers would be allowed to make trips to other vessels but only aboard one of the Royal Navy’s three “communication drifters.”

As enemy combatants—and now from a country in the throes of communist revolution (which ultimately failed in January 1919)—the German sailors had to be kept separate, too, from the British civilian population and military personnel nearby. This was, after all, the era of the first great “red scares,” the paranoid persecution and prosecution of socialists all over the world, including in the United States. Finally, vengeance played a role, too, in the decision to isolate the German sailors from each other and from the British: “We allow no communication whatsoever with the ships,” explained one British officer at the time: “It is as well to treat them as lepers after the way in which they have conducted the war for which they longed so much.”

Conditions on board the interned vessels were deplorable. Responsible for provisioning the internees, the German government did the bare minimum. Faced with shortages of food, medicine, and fuel at home, the result of postwar economic dislocations, civil unrest, and the ongoing Allied blockade of German ports, Berlin could not do much for the sailors. Morale dipped as the ships’ interiors accumulated grime and filth. With nothing to do, men lolled on the decks and in the dark.

There is evidence, too, that the revolutionary fervor at home had visited the ships, which makes sense since the revolution had been precipitated by a sailors’ mutiny in Kiel in early November 1918. When the ships arrived off the coast of Scotland later that month, they flew the red flag of the revolution. Later, British officers witnessed up-close the telltale signs of revolution among von Reuter’s men: “All proposed orders [by their commanding officers] are considered and countersigned by the men’s committee before they are executed.”

Von Reuter was ultimately in charge, but his crew and its revolutionary elements were hard to control. Moreover, the British authorities had no right under the Armistice agreement to board and guard the German ships themselves unless the Germans somehow violated the terms of the agreement.

When such a violation became apparent, however, around noon on 21 June 1919, it was too late for the British to be able to do much to enforce the terms of the Armistice.

Scuttling the Fleet

The Armistice agreement was set to expire on 21 June 1919, upon the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. It would have been clear to von Reuter, who claimed later to have read the newspapers, that the Germans were preparing to sign a treaty that would sharply curtail German naval power. Acting on what he read, he reported, von Reuter gave orders to have his ships sunk.

Yet planning began weeks earlier, according to historian Arthur J. Marder. Around the 17th or 18th, those plans culminated in written orders smuggled from ship to ship aboard one of the British mail drifters. Commanding officers were to act as soon as von Reuter gave the signal to scuttle. (The orders also described the signal—a certain manipulation of the flag at a certain time.) Crew therefore made sure that all watertight doors were in the open position, that all hatch covers were disengaged, that all ventilation openings were clear, and that all portholes were ajar.

After the signal and as the ships sank, crew and officers were to evacuate by way of the lifeboats.

But would the sailors follow these orders? Could the revolutionary elements be brought under control and trusted? Von Reuter soon found a way around this problem.

In anticipation of the singing of the Treaty of Versailles, the British allowed the repatriation of hundreds of internees, so von Reuter’s final preparatory act was to place his more revolutionary subordinates on the list to go home. He now had a more reliable class of men for carrying out this one last mission.

The British suspected that the Germans might try to scuttle the fleet and therefore planned for a surprise seizure at midnight on 21/22 June, when British military personnel would board the ships and take all measures—by force, even—to stop any snap attempts to scuttle. What the British had not expected, apparently, was that von Reuter would break the Armistice agreement by coordinating the sinkings ahead of time.

To make matters worse for the British, the officer in charge, Vice Admiral Sydney Fremantle, was out on exercises on 21 June, having been informed that the signing of the Versailles Treaty would be delayed by a few days.

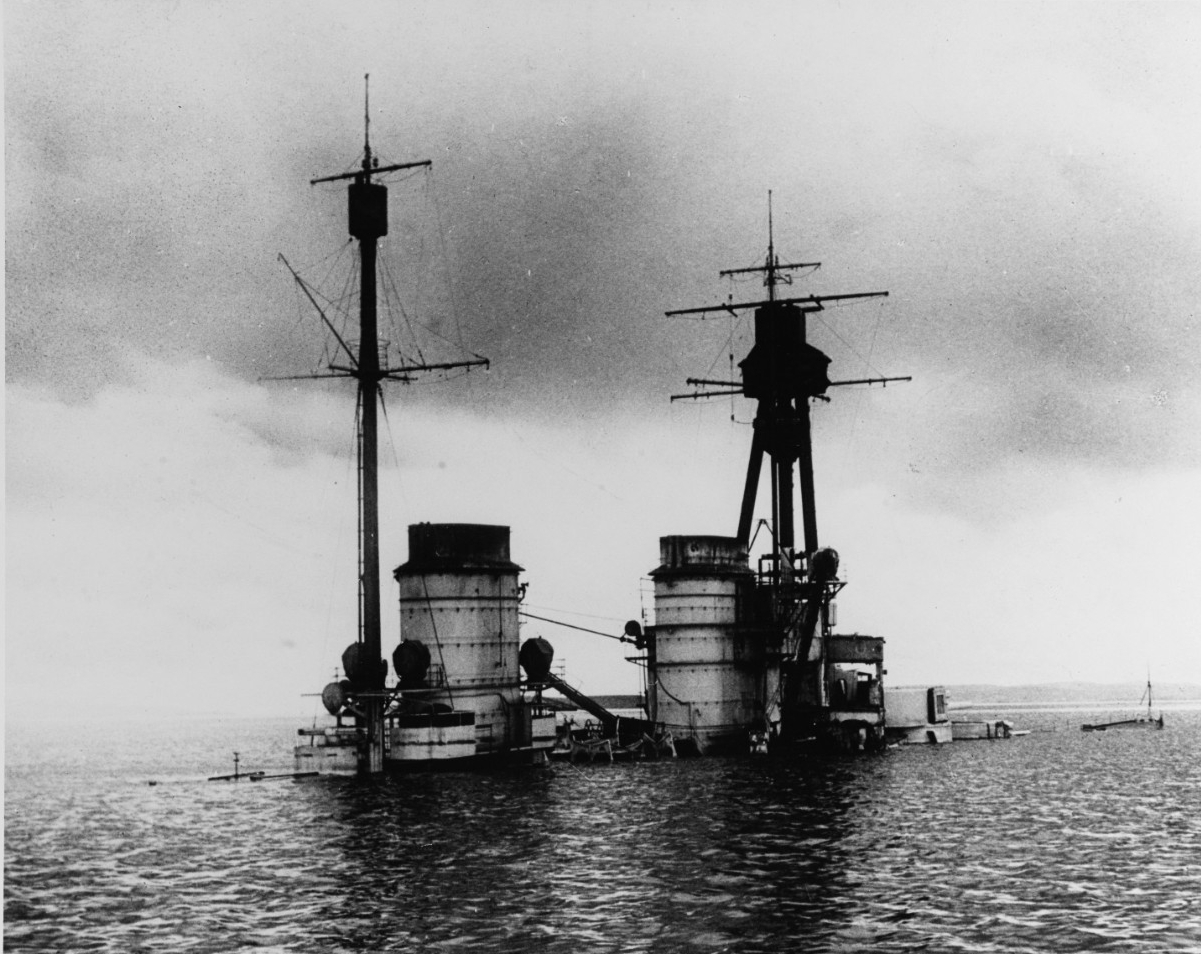

And so, in late morning on 21 June, von Reuter gave the signal to scuttle. Sailors on each ship opened seacocks and valves, already loosened in preparation, and the water rushed in.

Only at noon, some 40 minutes into the process, did British personnel notice that something was amiss. Each ship now raised the German ensign on its mainmast, and v on Reuter’s own ship, Friedrich der Grosse, was developing an obvious list to starboard.

At 12:20, Vice Admiral Fremantle learned by wireless messages that the dreaded scuttle was underway. He directed his ships back to Scapa Flow and issued orders to the personnel already there: Stop the Germans. Royal Navy personnel at Scapa Flow responded by towing some of the sinking ships to shallower waters and beaching them and, in some cases, using deadly fire to try to force German sailors to stay on their vessels and undo what they had done.

By the time Fremantle and his ships arrived back at Scapa Flow, it was too late. Almost all of the ships were either sunk, sinking, or beached but full of water.

Lifeboats bobbed in the bay as British vessels picked up the survivors.

The Context

Von Reuter’s unilateral decision to go against the wishes of the government of Germany by sinking the fleet at Scapa Flow makes sense in the context of German politics in 1919. Former officers, especially high-ranking ones, saw the government’s willingness to sign the Treaty of Versailles as a betrayal of the German people. They encouraged civil disobedience and even counterrevolution—anything to punish the Republic (Germany’s first democratic regime) for signing the treaty.

Von Reuter’s action became one in a series of actions against Germany’s duly elected government in the interwar period. In March 1920, Wolfgang Kapp, Erich Ludendorff (Chief of Staff during World War I), and others tried to overthrow the Republic and replace it with a military dictatorship. One of their complaints against the present democratic regime was the Treaty of Versailles: No power that had signed the dreaded document could have legitimacy, they argued. Germany’s workers and civil servants disagreed and quashed the coup. In November 1923, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis—still a right-radical group on the fringes of German political life—staged their own coup, known as the Beer Hall Putsch, in Munich to bring down the Republic for its assent to the Treaty of Versailles.

The Treaty of Versailles and reparations became key political issues in interwar Germany, where elected leaders had considerable trouble charting a course between accommodation and revision.

Von Reuter was one of the early proponents of revision—before the treaty had even been concluded—and he used a tactic that became familiar in the 1920s. Indeed, von Reuter helped establish a pattern, visible in retrospect, of German violations of international agreements that culminated in that country’s illegal rearmament under Hitler in the 1930s.

—Adam Bisno, PhD, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division, June 2019

___________

Further Reading

Gerwarth, Robert, and John Horne. “Vectors of Violence: Paramilitarism in Europe after the Great War, 1917–1923.” Journal of Modern History 83 (2011): 489–512.

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World. New York: Random House, 2002.

Marder, Arthur J. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904–1919. Vol. 5: Victory and Aftermath, January 1918 to June 1919. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970.

Marks, Sally. “Mistakes and Myths: The Allies, Germany, and the Versailles Treaty, 1918–1921.” Journal of Modern History 85 (2013): 632–659.

Vasick, George, and Mark Sadler, eds. The Stab-in-the-Back Myth and the Fall of the Weimar Republic: A History in Documents and Visual Sources. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

Weitz, Eric. Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.