H-060-1: USS Conestoga (AT-54) Vanishes–25 March 1921

Samuel J. Cox, Director, Naval History and Heritage Command

For 95 years, the loss of the U.S. Navy fleet tug Conestoga (AT-54) and her 56 crewmen would remain one of the greatest unsolved maritime mysteries, particularly since it occurred in the era of wireless radio communications. It was a major embarrassment that the U.S. Navy tried to forget, and there were lessons not learned.

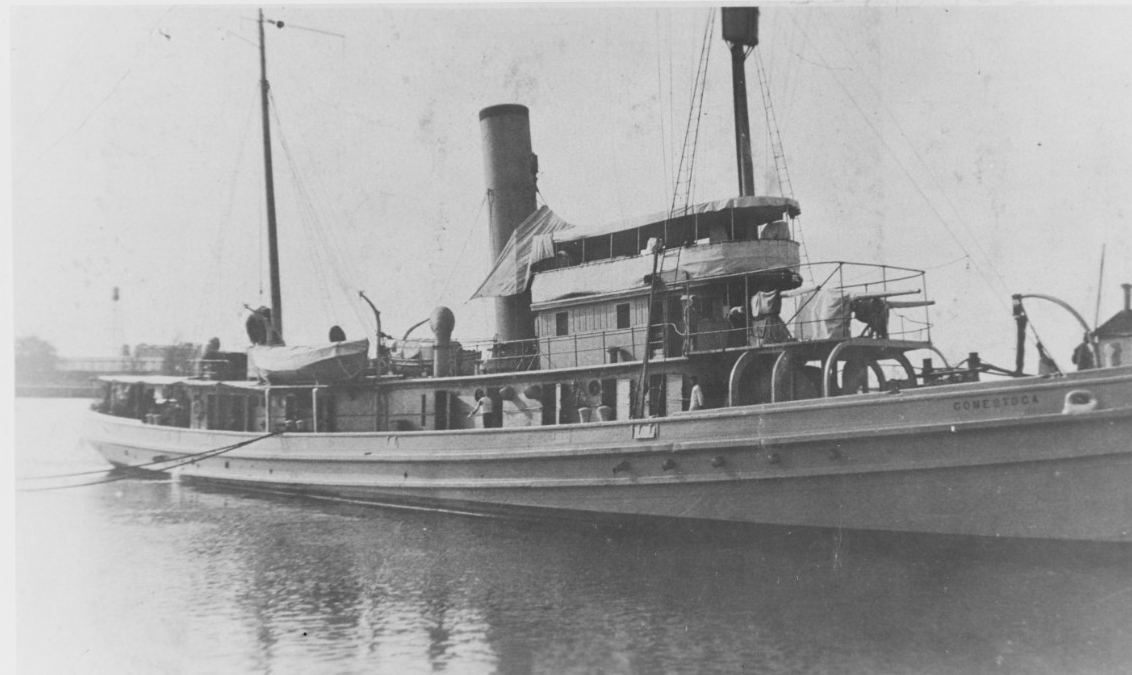

The tug Conestoga was built in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1904 for commercial service towing coal barges. She was acquired by the U.S. Navy on 14 September 1917 for use as a fleet tender and minesweeper, designated SP. 1128, but retaining her commercial name. She was initially assigned to the submarine force and underwent modifications for service overseas. During World War I, she performed towing services along the eastern coast of the United States. She escorted convoys to Bermuda and the Azores, and served with the American patrol detachment in the Azores. She finished the war attached to Naval Base No. 13 (Azores). After the war, she was assigned harbor tug duty at Norfolk. As part of the Navy-wide ship classification and hull-numbering scheme change, she was designated AT-54 on 17 July 1920.

Conestoga then received orders to sail to American Samoa to serve as station ship at Tutuila. She departed Norfolk towing U.S. Navy coal barge YC-658 on 18 November 1920, arriving at San Diego via the Panama Canal on 7 January 1921. She then proceeded to Mare Island for voyage repairs, including work on her faulty bilge pump system.

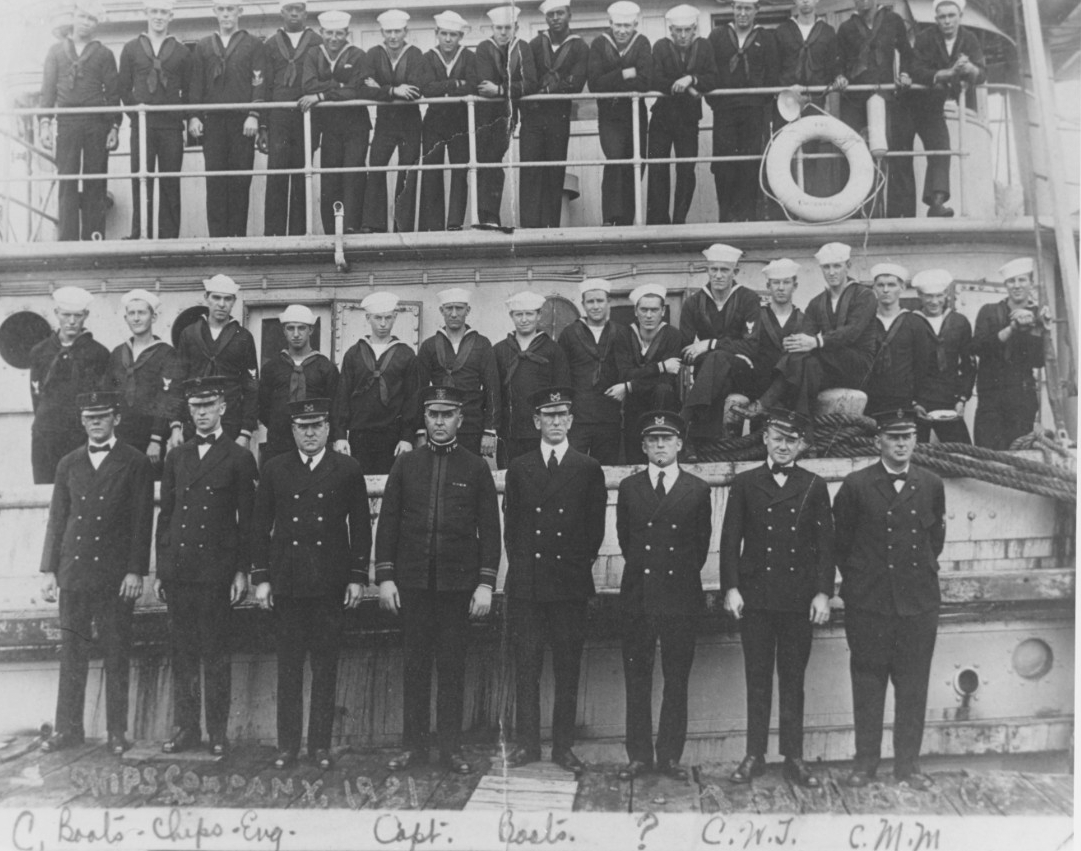

On 25 March 1921 at 0900, Conestoga departed Mare Island bound for American Samoa via Pearl Harbor, under the command of Lieutenant Ernest Larkin Jones. Aboard were three other officers and 52 crewmen. She was probably towing U.S. Navy coal barge YC-478, but this is not 100 percent certain. Some accounts also claim the barge was carrying a secret cargo of sea mines, but this is also unconfirmed. The weather conditions were clear, but the seas were heavy and winds picked up speed to gale force as the day went on.

Conestoga should have arrived at Pearl Harbor about 5 April, but did not. A message sent in error on 6 April indicated a safe arrival. As a result, neither naval authorities in Pearl Harbor nor San Francisco realized Conestoga was missing until 26 April and commenced what became the largest air-sea search in history until Amelia Earhart went missing in 1937. Over 60 U.S. Navy ships and 15 aircraft were involved in the search, including all destroyers and submarines based at Pearl Harbor. The initial search was concentrated around Hawaii. Although a life-jacket marked as belonging to Conestoga washed ashore near San Francisco, Navy authorities assumed it had fallen off Conestoga either just before her arrival or just after her departure from Mare Island. The commandant of the 14th Naval District (Hawaii) reported that there was no trace of Conestoga and her loss was probable.

During the search, the Pearl Harbor-based submarine R-14 (SS-91) ran out of usable fuel (some fuel had become contaminated) and went adrift about 100 nautical miles southeast of the Big Island of Hawaii. R-14 was a small diesel-electric coastal and harbor defense submarine with a crew of two officers and 27 enlisted men, under the acting command of Lieutenant Alexander Dean Douglas. The radio malfunctioned, the battery had insufficient capacity to reach Hawaii, and the sub only had rations for five days. R-14’s engineering officer, Lieutenant Roy Trent Gallemore, devised a way to rig a foresail made of eight hammocks using the torpedo-loading crane. This gave the sub a speed of about one knot and steerage way. Additional bedding was sewn together and rigged to the radio mast as a mainsail, and then more bedding was used to rig a mizzen mast. The sub then sailed for 64 hours at about three knots to Hilo, and was able to enter port on battery power. Lieutenant Douglas received a letter of commendation for the resourcefulness of his crew from the submarine division commander, Commander Chester W. Nimitz.

Although Nimitz may have appreciated their resourcefulness, R-14 was treated by the press as a laughing stock at the Navy’s expense. In fact, the press coverage of the loss and search for Conestoga was extensive, nation-wide, sensationalized, and generally very negative, running along the lines of—with the technology of 1921 (i.e., radio)—how could the Navy completely lose a ship and 56 men? U.S. Navy standing with the public had taken a precipitous drop after the end of World War I as the country quickly turned isolationist in response to the bloodbath of the conflict. Some considered that the primary cause of the terrible war was the naval arms race between the British and the Germans. Calls for the elimination of submarines, battleships, and even entire navies became more vociferous and would lead to the Washington Naval Conference later in 1921, with massive naval force cuts over the U.S. Navy’s objections. The very public mudslinging match between Vice Admiral William S. Sims (Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Operating in Europe, 1917–19) and Josephus Daniels (Secretary of the Navy, 1913–21) over how prepared the Navy was (or wasn’t) for the war didn’t help public perception. (Daniels is most commonly known—and blamed—for ending the Navy’s rum ration, although he instituted numerous positive reforms. He also energetically instituted segregation, in alignment with the policy of the Wilson administration, in what had previously been an integrated U.S. Navy at the enlisted ranks. He was among the most outspoken segregationists to hold the office of the Secretary of the Navy, and his role in the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 was particularly appalling.) The loss of Conestoga also resulted in one of the more unseemly episodes of attempted blame-shifting between senior U.S. Navy admirals. In short, it was a public relations disaster.

As the first search began to wind down, the steamship Senator reported finding a derelict and barnacle-encrusted lifeboat with the letter “C” on the bow about 650 nautical miles west of Manzanillo, Mexico, and about 30 nautical miles from Clarion Island on 17 May 1921. This prompted another massive and fruitless search. Senator did not recover the boat, but found an identification number, M5535 B, which, however, matched no Navy records. Senator did keep the “C.” After finding nothing during the second search, the Navy officially declared that Conestoga and her entire crew were lost on 30 June 1921; the fate of the crew unknown, but presumed dead.

In 2009, the fishing vessel Pacific Star was conducting a systematic scientific survey, using side-scan sonar for seabed mapping, in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary off San Francisco Bay under the auspices of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Coast Survey. Although over 400 ships have been lost in the area dating back to the 1500s, the sonar detected a vessel on the bottom in 189 feet of water where none was reported to have sunk. The location was 3.1 nautical miles southeast of Farallon Island, about 27 nautical miles from Golden Gate.

In 2014, the research vessel Fulmar returned to the site for a more detailed survey. Using a remotely-operated vehicle (ROV), the wreck was determined to be a 170-foot steel-hulled steam tug sitting upright on the bottom oriented as if trying to reach Fisherman’s Cove, an anchorage near the lighthouse and U.S. Navy radio direction finding station (1905 to late 1930s). The superstructure had collapsed into the hull. The most distinguishing feature was a single 3-inch/50-caliber deck gun on the collapsed foredeck. With the imagery and data, NOAA then conducted extensive archival research, concluding that the only possible candidate for this wreck was Conestoga. After reviewing NOAA’s data, NHHC confirmed that the wreck was Conestoga.

Another detailed survey was conducted by NOAA in October 2015, with a smaller ROV that could reach interior spaces. Besides the NOAA team, NHHC Underwater Archaeologist Alexis Catsambis and Rear Admiral Markham Rich (Navy Region Southwest) were also aboard. Commander Third Fleet Vice Admiral Nora Tyson also visited the ship. The intent of this mission was to gather as much data as possible in an attempt to determine the exact cause of loss. The exact cause actually could not be determined; however, evidence suggested a most plausible scenario.

Conestoga most likely ran into serious trouble not long after crossing the San Francisco Bar in the increasingly heavy seas. The towing wire on the winch suggests a tow was lost, but was not the cause of Conestoga’s loss, as the end of the line is professionally tied down. Navy records indicate coal barge YC-478 was lost en route Pearl Harbor in 1921, but there is no date or cause to confirm this was Conestoga’s tow. Conestoga may have been taking on water due to her bilge pump system not working correctly (which had just been repaired) or was just taking on more water than the pumps could handle. Faced with going down in the open ocean, the commanding officer attempted to make it to a cove in the lee of Farallon Islands. This would have been an act of desperation as the site was the location of five other shipwrecks between 1858 and 1907. It is possible Conestoga lost her ability to steer as both rudders are hard over outside their normal range, although that may also be a function of hitting the bottom stern first. The Conestoga appears to have been swamped and sank quickly, hitting the bottom upright, about three miles short of the anchorage, and probably at night due to lack of witnesses. None of her crew survived the sinking, regardless of how long they might have lasted in the water. The sad fact is that both Navy searches were over 2,000 miles away and a month later than the actual location and time of the sinking.

One mystery that remains unresolved is whether or not Conestoga made a distress call. On 13 May 1921, San Francisco Chronicle reported that Conestoga made a garbled radio transmission on 8 April that she was battling a severe storm and the tow was possibly lost. The article does not state who received the transmission. This certainly does not fit with the date of her probable loss. It is possible the paper just got the date wrong, or the report was relayed by another ship or station very time late. It would have occurred before it was known she was missing. The possibility of a hoax transmission is low, although the paper’s later source could have been a hoax. The current assessment is that Conestoga probably did make a radio distress call the night of 25–26 March 1921, but no one in a position to do anything about it received it, or took action on it.

It also possible the lifeboat found west of Mexico could have drifted from the site of the sinking, although the description provided by steamship Senator suggested the boat had been in the water a lot longer. Interestingly though, photos of Conestoga show a lifeboat with the letter “C” affixed to the bow (which leaves me with the question, I wonder whatever happened to the “C?”).

In March 2016, NOAA and NHHC made a joint announcement of solving the 95-year-old mystery of the loss of the Conestoga at a ceremony attended by family members of those crewmen lost with the ship. As the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Energy, Installations and Environment (ASN EI&E), Vice Admiral (retired) Dennis V. McGinn, stated at the ceremony, “In remembering the loss of the Conestoga, we pay tribute to her crew and their families and remember that, even in peacetime, the sea is an unforgiving environment.”

The wreck of Conestoga is protected as a military grave under the Sunken Military Craft Act (for which NHHC is the Federal Executive Agent) and by the National Maritime Sanctuaries Act (for which NOAA is the Federal Executive Agent).

For more on other U.S. Navy ships lost with all-hands due to weather and accident please see attachment H-060-2.

Sources:

Conestoga II (S. P. 1128) (DANFS, NHHC)

“95-Year-Old Lost US Navy Ship Mystery Solved” (24 March 2016, NHHC)

“USS Conestoga (AT-54) Wreck Site (1921): A Navy Tug Sunk off the Coast of San Francisco” (NHHC)

“USS Conestoga – 100 Years Since Departure.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – National Marine Sanctuaries.

Marx, Deborah E., Robert V. Schwemmer, and James P. Delgado. “USS Conestoga (shipwreck and remains).” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. National Park Service.