H-Gram 030: USS England, U-505 Capture, and NC-4’s Transatlantic Crossing

21 May 2019

Contents

- 75th Anniversary of World War II: USS England Sinks Six Japanese Submarines, May 1944

- 75th Anniversary of World War II: U-505 Captured by USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) Hunter-Killer Task Force, 9 June 1944

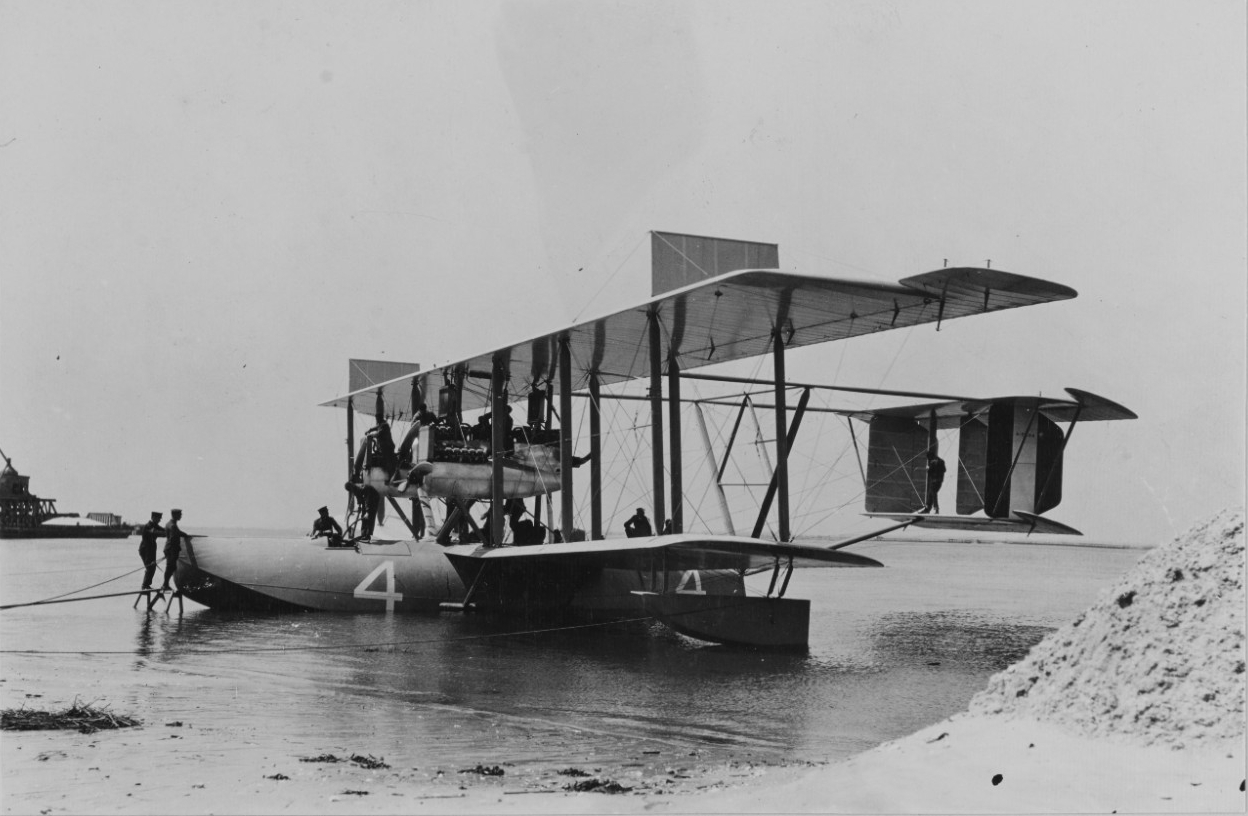

- Naval Aviation Milestone: First Transatlantic Crossing by an Aircraft, May 1919

This H-gram will cover the unprecedented (and never duplicated) sinking of six Japanese submarines in 12 days by the destroyer escort USS England (DE-635) in May 1944; the capture of the German submarine U-505 by the USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) hunter-killer task group on 9 June 1944; and the harrowing first transatlantic crossing by an aircraft, U.S. Navy flying boat NC-4 in May 1919.

As always, further dissemination is welcome and encouraged for crews to gain a greater appreciation of the history of our Navy and the valor and sacrifice of those who served before. In addition, “back issue” H-grams can be found here—in addition to a lot of other great history at Naval History and Heritage Command’s website.

75th Anniversary of World War II

USS England Sinks Six Japanese Submarines, May 1944

Over the course of 12 days in late May 1944, the destroyer escort USS England (DE-635), commanded by Lieutenant Commander Walton B. Pendleton, sank six Japanese submarines in an area between the Admiralty Islands (north of New Guinea) and Truk. This included five Japanese submarines of a line of seven that had been stationed in an attempt provide reporting on U.S. fast carrier task forces, which the Japanese were anticipating would pass through the area. This unprecedented action was possible because U.S. Navy radio intelligence provided accurate warning and locating information on the Japanese submarines, and due to the capabilities of the new Mark 10 “Hedgehog” anti-submarine weapon system, which was entering service in the Pacific. Although England received credit for the kills, in almost all cases the submarines were first detected by other ships in the ASW hunter-killer group of which England was a part (which knew where to look due to the intelligence), so teamwork was essential to the outcome.

The Japanese submarines that were sunk had been previously responsible for sinking the U.S. destroyer Henley (DD-391), LST-342, several Allied and neutral merchant ships, as well as badly damaging the British battleship HMS Ramillies (with a midget submarine), and launching one of the midget submarines that attempted to enter Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. All 378 Japanese crewmen aboard the six submarines were lost, with no casualties to any of the U.S. ships engaged (although over 150 Allied personnel had been killed in ships previously sunk by those submarines).

England would continue combat operations in the Western Pacific until she was hit by a kamikaze off Okinawa in 1945, a strike that killed 37 men and wounded 25. Although the ship survived, her damage was too extensive to be considered worth repairing and she was sold for scrap in 1946. England was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation and Lieutenant Commander Pendleton the Navy Cross. CNO Ernest J. King pronounced that “there’ll always be an England in the United States Navy,” although this hasn’t been true since 1994.

For more on the USS England and the war records of the Japanese submarines that were sunk, please see attachment H-030-1.

U-505 Captured by USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) Hunter-Killer Task Force, 9 June 1944

I was planning to do an item on the capture of German submarine U-505 on 9 June 1944 by a boarding party from destroyer escort USS Pillsbury (DE-133), for which the boarding team leader, Lieutenant (Junior Grade) Albert David, would be awarded the Medal of Honor, the only one awarded for action in the Atlantic Theater in World War II (he would also earn two Navy Crosses in other actions). However, to place the action in proper context is going to take me more time and research. I will produce a more comprehensive Battle of the Atlantic update in a few months.

Although May 1943 is generally accepted as the point at which the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic turned, the Germans were an extremely resourceful and determined foe, who weren’t about to quit. By June 1944 the U-boats were more the hunted than the hunter, but it took an extraordinary combination of Intelligence, code-breaking, operations analysis, new weapons and sensor technology, and just plain increased number of escort ships (especially the use of escort carriers in a hunter-killer role) in order to defeat them, not to mention the courage of the crews of U.S. Navy ships. The Germans had tricks up their sleeve, too, particularly the new acoustic homing torpedoes, which claimed a number of U.S. and Allied warships. The capture of two G7es Zaunkönig T-5 acoustic homing torpedoes aboard U-505 was an even bigger intelligence bonanza than the Enigma machines and codebooks—which were only good for a month—and enabled improvements to the Foxer acoustic countermeasure and aided development of U.S. acoustic torpedoes used against the Japanese at the very end of the war. The Germans referred to the T-5 as the “destroyer-cracker,” as it was generally employed against convoy escorts rather than transports and merchant ships.

On 29 May 1944, the escort carrier USS Block Island (CVE-21) was hit and sunk by two of three torpedoes from U-549 before the submarine then badly damaged destroyer escort USS Barr (DE-576) with a T-5 acoustic torpedo, killing 16 men on the ship. Block Island’s escorts then sank U-549 (with all 57 hands lost) and rescued 951 crewmen of the escort carrier. Amazingly, only six of Block Island’'s crew were lost, although the pilots of four of the six Wildcat fighters aloft at the time were also lost while trying unsuccessfully to reach land. Block Island was the only U.S. aircraft carrier lost in the Atlantic. From 1943 and into 1944 there were several epic close-quarters duels between U.S. ships and German U-boats (involving ramming, small-arms fire, and throwing hand-grenades, hatchets, knives, and even coffee mugs—even the use of fists), in each case demonstrating unbelievable courage on the part of both U.S. and German crews. These actions include USS Borie (DD-215) versus U-405 in November 1943; USS Buckley (DE-51) versus U-66 (one of the all-time most effective U-boats) on 6 May 1944; and the U.S. Coast Guard cutter USS (in wartime) Campbell versus U-606 in February 1943. I will cover these extraordinary acts of valor in a future H-gram.

Naval Aviation Milestone

NC-4: First Transatlantic Crossing by an Aircraft, May 1919

On 14–15 June, 1919 British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown flew a modified Vickers Vimy bomber from Newfoundland to a crash landing in Ireland, completing (technically) the first non-stop transatlantic crossing by an aircraft. This feat knocked off the front pages the Atlantic crossing by the U.S. Navy flying boat NC-4, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Albert Cushing Read, which had landed at Lisbon, Portugal, on 27 May 1919. Although the first plane to fly across the Atlantic, NC-4 had taken 23 days and multiple stops to do so, overcoming numerous technical problems and hazards along the way. Two other Navy flying boats (NC-1 and NC-3) didn’t make it as far as the Azores Islands (in the air), although all crewmen were safely recovered. Among the aviators involved in the flight were Commander John H. Towers (Naval Aviator No. 3 and overall commander of the mission, in NC-3) and Lieutenant Commander Marc “Pete” Mitscher (in NC-1), both of whom would go on to distinguished naval aviation leadership roles in the interwar years and during World War II. In addition, U.S. Coast Guard Aviator No. 1, Lieutenant Elmer Fowler Stone, was one of the pilots of NC-4. Although NC-4’s flight quickly sank into relative obscurity, it nevertheless represented a great milestone in aviation history. The Navy donated the original aircraft to the Smithsonian, which couldn’t find a place to display it (supposedly due to its large size,) but the Smithsonian loaned it back to the Navy and it is on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. Please see attachment H-030-2 for more on NC-4’s epic flight.