Industrial Base

The resources of this country are in my opinion fully adequate to create and maintain a navy…The U.S. abound with every material, requisite for the building and equipping ships of war.

Joshua Humphreys, designer of USS Constitution, 1812

Founding the U.S. Navy: Construction before 1812

After independence, Americans disdained the taxes necessary to fund a navy, until foreign piracy convinced Congress in 1794. After a slow start, attacks by revolutionary France prompted a rapid expansion of the new US Navy. By 1801, US-French relations had calmed and naval spending was severely cut. Not until war with Britain came did a new building program begin.

This model of USS Constitution illustrates how she may have appeared while refitting just prior to war in 1812. Among six frigates authorized by the Act to Provide a Naval Armament in 1794, Constitution took almost three years to complete and ran nearly 300 percent over budget. Such was the cost of building the first ships and the first navy yards at the same time. Not until 1813 would a new class of frigates benefit from the navy yards, building frigates in a quarter of that time at less expense.

Pictured here is the U.S. frigate Essex, built in Salem, Massachusetts in 1799. During the hostilities with France, American merchants felt obliged to support the navy, since it was first established to protect their trade. After Congress authorized the induction of publicly-funded vessels into the navy on 30 June 1798, merchants in port cities all along the seaboard pooled their resources for shipbuilding. In all, five frigates and five smaller vessels were constructed for the navy. Of these only Essex survived until 1812 because of her superior sailing qualities.

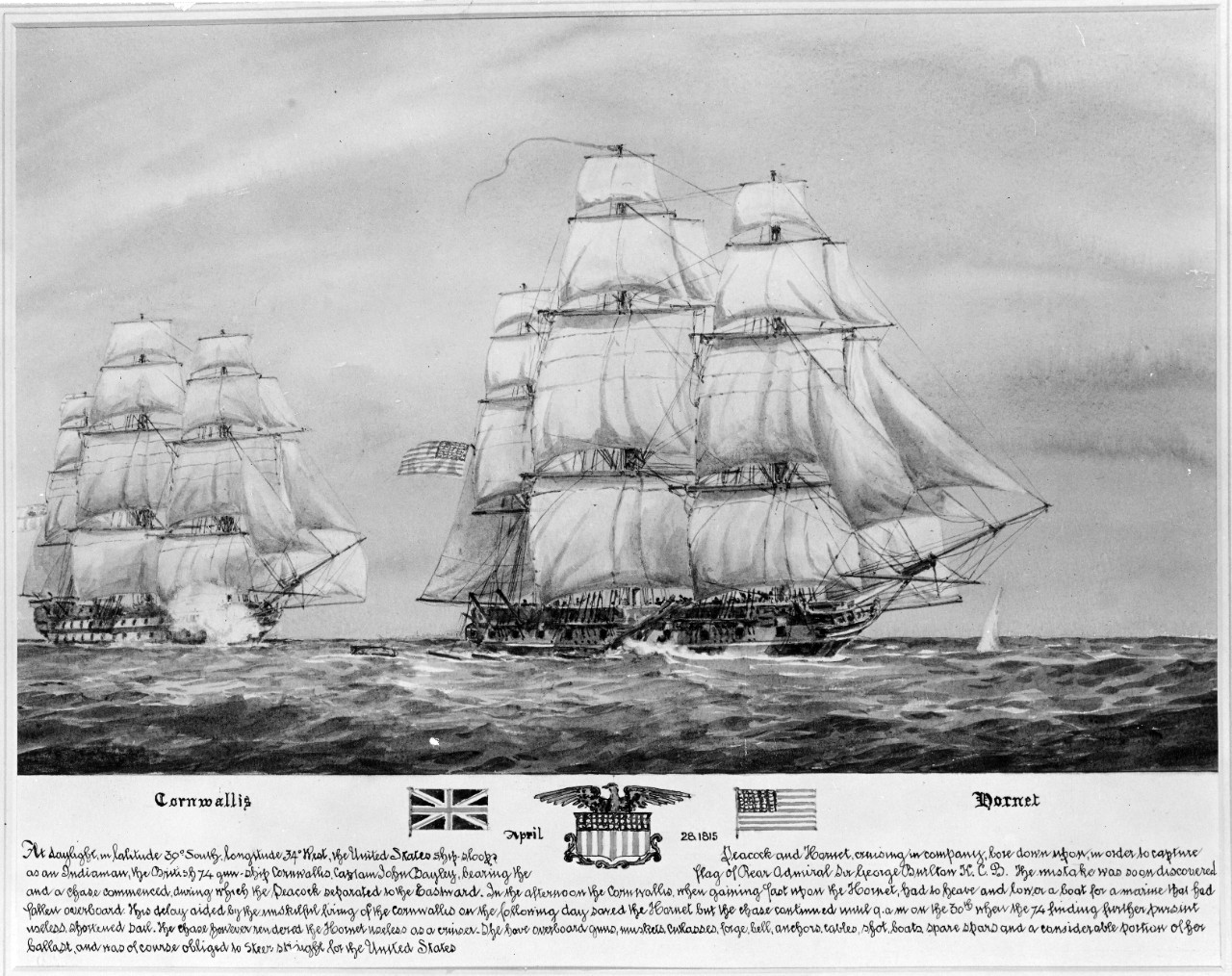

USS Hornet, pursued here by a British ship of the line, was one of only two naval vessels constructed in the decade before the War of 1812. She was built at a private shipyard in Baltimore in 1805. Wasp, of the same class, was built at the Washington Navy Yard a year later. When both vessels were examined shortly before the war, Hornet was found to be much decayed while Wasp was quite sound. Despite successes in their own yards, the navy continued to rely on private yards to build warships before and during the War of 1812, because budgetary restraints left most navy yards underfunded.

Seen in battle on September 5, 1813, with HM Brig Boxer, Enterprise was the smallest sea-going vessel in the Navy. Built as a schooner on Maryland’s eastern shore in 1799, she had a successful and famous career against French and Tripolitan enemies before being re-rigged as a brig in 1811. Small vessels like Enterprise were unpopular in the Navy, despite being essential for patrolling and inshore work. Rather than ordering and maintaining such vessels, the Navy more often purchased them ‘used’ from merchants or the revenue service in times of need and sold them afterwards, making Enterprise’s longevity quite unique. Both commanding officers died in battle, Enterprise took Boxer to Portland, Maine.

Shipbuilding Resources and Industries of the Early U.S

When it is considered that one 74 gun ship requires 2,000 large oak trees, equal to the estimated produce of 57 acres, the importance of securing for public use all that valuable species of oak which is found only on the southern seaboard, is sufficiently obvious.

William Jones, Secretary of the Navy, 1814.

The early U.S. was well equipped for naval construction: abundant natural resources, a host of small industries, and skilled shipbuilders in its many private yards. Even so, building a navy from scratch proved much more difficult and costly than anticipated.

“…we have a furnace near this village in full operation & calculated to supply a large quantity at short notice upon terms as reasonable perhaps more so than any other furnace…We can deliver shot at Sacketts harbor or Oswego as may be required...”

James Lynch, Oneida Iron Manufacturing Co. to Paul Hamilton, Secretary of the Navy, 1812.

Weight of Timber

Good timber - the most important ingredient in shipbuilding – was also the county’s most abundant resource. Premium was placed upon the hardwoods that gave shape and strength to a vessel’s frame. Light, flexible softwoods selected from the tallest trees were ideal for masts. All wood had to be seasoned before installation to promote longevity in a saltwater climate. If maintained, well-built vessels could last for decades; cutting corners ensured a rotten ship within a few years.

Feel the difference in weight between these pieces. Heavier timber was denser; that is, stronger. Live oak was the heaviest of all American hardwoods, and naturally salted by its brackish environment, making it resistant to rot at sea. However, light softwood was necessary for masts, to keep a ship’s center of gravity low, and to let rigging flex a little, which preserved it better under stress.

Weight of Shot

Roundshot (cannonballs to landsmen), the principal naval weapon in 1812, consisted of a solid or hollow iron sphere designed not to explode but to batter a vessel into surrender. Dozens of American furnaces cast shot for the US Navy. For instance, the shot with which USS Constitution defeated HMS Guerrière was cast at the Charlotte foundry, in Middleborough, Massachusetts.

Feel the difference between the varying weights of these roundshot. A warship’s power was measured by its “weight of shot”: the sum of iron it could fire in one broadside. The larger American frigates that won the great victories of 1812 threw 24 pound shot from their main battery. The British frigates opposed to them fired 18 pound shot. This disparity gave the US Navy a great advantage in one-to-one encounters.

Government Shipyard Work

The President Frigate went into the Navy Yard at New York for some partial repairs… Since then two frigates…and two Sloops of war…have been built and fitted here, and have sailed…although every article of their armament & rigging has been transported from New York in despite of obstacles almost insurmountable…

Comm. Isaac Chauncey to Secretary of the Navy William Jones, August 10, 1814.

Under the Navy Department, federal shipyards became the new infrastructure for stockpiling shipbuilding material and providing oversight. Although underfunded, by 1813 the yards significantly reduced the time and expense required to build new ships.

Unfinished Knee, Accession # 59-139-B.

This section of timber is cut in the distinctive “L” shape of a knee. Among the most crucial parts of a ship, knees fastened the horizontal deck beams of a ship to the vertical timbers of its hull, and had to support great weight. Additionally, before the widespread use of iron this shape had to be found in nature – an important consideration in timber selection. The selecting, felling, transport, and working of timber was usually the task of federal employees who worked at or in conjunction with the navy yard.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Constitution Knee, Accession #59-139-B.

This knee helped support one of USS Constitution’s two upper decks, which together carried over 50 guns weighing in excess of 120 tons. Joshua Humphreys, the ship’s designer, specified live oak – only found in remote southern coastal regions - for such structural pieces because of its great strength, natural curves, and innate resistance to salt-water. After being cut in Georgia, the unfinished wood was sailed to Boston where Constitution was being built in a new federal navy yard. This piece was removed during the 1927 rebuild.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Constellation Treenail, Accession # 64-24-A

This oak tree nail (pronounced “trunnel”) fastened planking to the frame of USS Constellation. Unlike metal nails, the blunt treenail would be fitted into a pre-drilled hole. While iron nails quickly corroded when in direct contact with sea water, accelerating rot in the surrounding wood, treenails swelled and became more secure. Constellation was built in Baltimore, the only building site of the original frigates not purchased as a federal navy yard – Washington was later selected instead.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Frigate Cut-away, Accession # 86-270-A.

This cutaway of a frigate reveals the arrangement of decks within the hull. Note the role of knees (L-shaped timbers) in bearing the load. The narrowing of the hull higher up is called tumblehome, and kept heavy guns nearer the centerline for stability. The planks are fastened here with metal spikes, but wooden treenails were more often used. By 1813, U.S. Navy shipyards could expect to build a frigate at a fraction of the time and cost possible in the 18th century.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Eprouvette Mortar, Accession #61-81-BN

This eprouvette mortar was a tool for testing the quality of gunpowder. Firing a standard weight of shot at a fixed angle and charged with a standard weight of powder - typically one pound – the distance the shot flew became a measurement of the gunpowder’s efficiency. The Navy had an important powder magazine near the Washington Navy Yard and would have needed mortars like this one for proving powder. Standardized testing was especially necessary since the navy contracted out gunpowder manufacturing.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Private Contractors

You state, Mr. Anderson sent from the Magazine…400 Barrels of powder…at the rate of seventy two cents per pound…I have noticed the contract of Bullus, Decatur & Rucker, of the 9th. February 1813, to manufacture and deliver to the Agent…powder, at 13½ cents per pound…These things must be explained…

Secretary of the Navy Jones to Navy Agent and Businessman John Bullus.

The early Navy relied on private firms to furnish materials for shipbuilding. It appointed agents to make contracts and disperse payments on its behalf. Scores of small businesses cast guns, sewed sails, and laid rope for vessels building at federal shipyards. Some private yards – mostly in Baltimore - even built entire vessels under contract for the Navy.

Revere Spike, Accession #62-84-A.

This copper spike was made under contract in the 1790s by Paul Revere of revolutionary fame, for the frigate Constitution, then building in Boston. The ends were hammered flat to fit tightly in the hole, like a modern rivet. Contracting the various work of shipbuilding out to small local firms was the usual method for the Navy in its early days. This piece was removed in the 1920s during rebuilding.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Constitution Flashing, Accession # 68-739-A.

This copper flashing was nailed to the step of a ladder on the frigate Constitution to save it from wear and tear. It is pierced for nails, probably also of copper, which would have fastened it securely. Many simple pieces like this helped prolong the life of a wooden vessel in the early 19th century, and could be readily manufactured by small private firms with few employees.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

Constitution Spikes, Accession # 59-139-B. Note the white corrosion.

These copper spikes were removed from the frigate Constitution during her 1927 and 1970s

rebuilds, respectively. They probably would have fastened down those timbers that would be placed under high stress by the rigging, or they could have secured copper sheathing to the hull. In the latter case, an enormous number would have been needed. Since private manufacturing firms were small, government contracts were made as soon as possible to allow firms time to produce the necessary quantity.

This artifact is on display in the Constitution Gun Deck area in Bldg. 76.

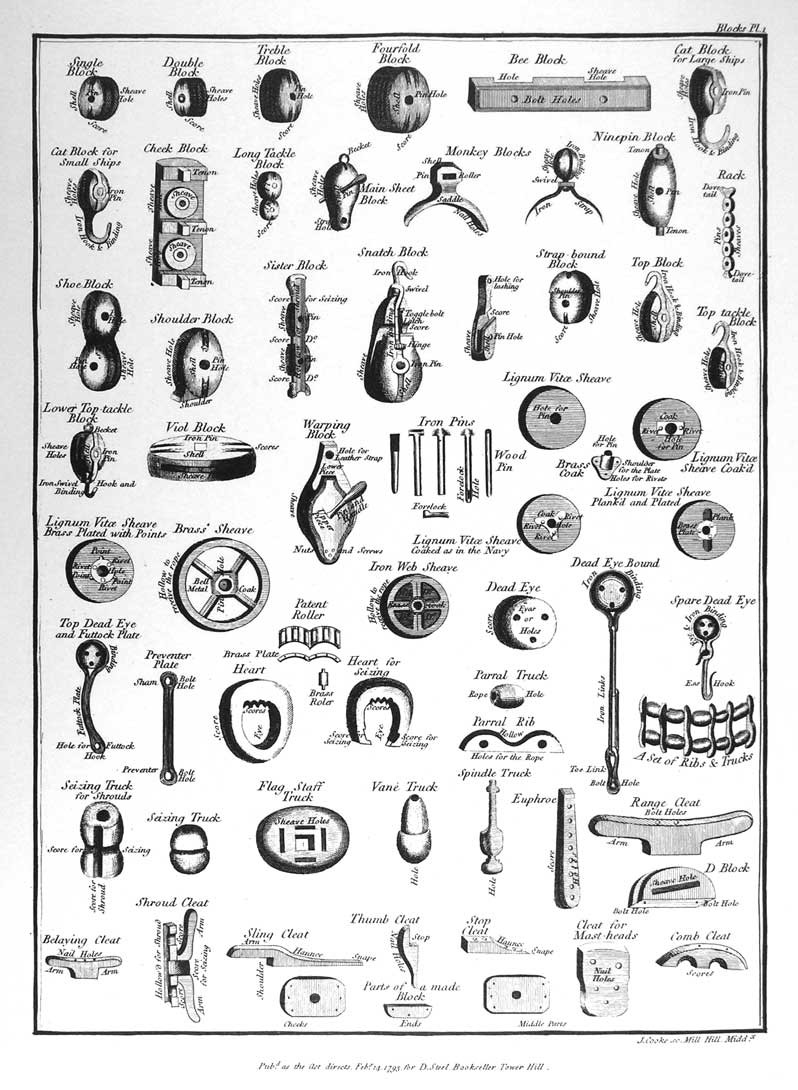

Pictured here are the tools of the block-maker’s trade. Block-making, a tedious but relatively well-paying job, provided each warship with the hundreds of blocks (pulleys to landsmen) needed to work the sails and guns. The Navy Yard’s block shop, located not far from where you’re standing, was burned in the 1814 fire during the British invasion.

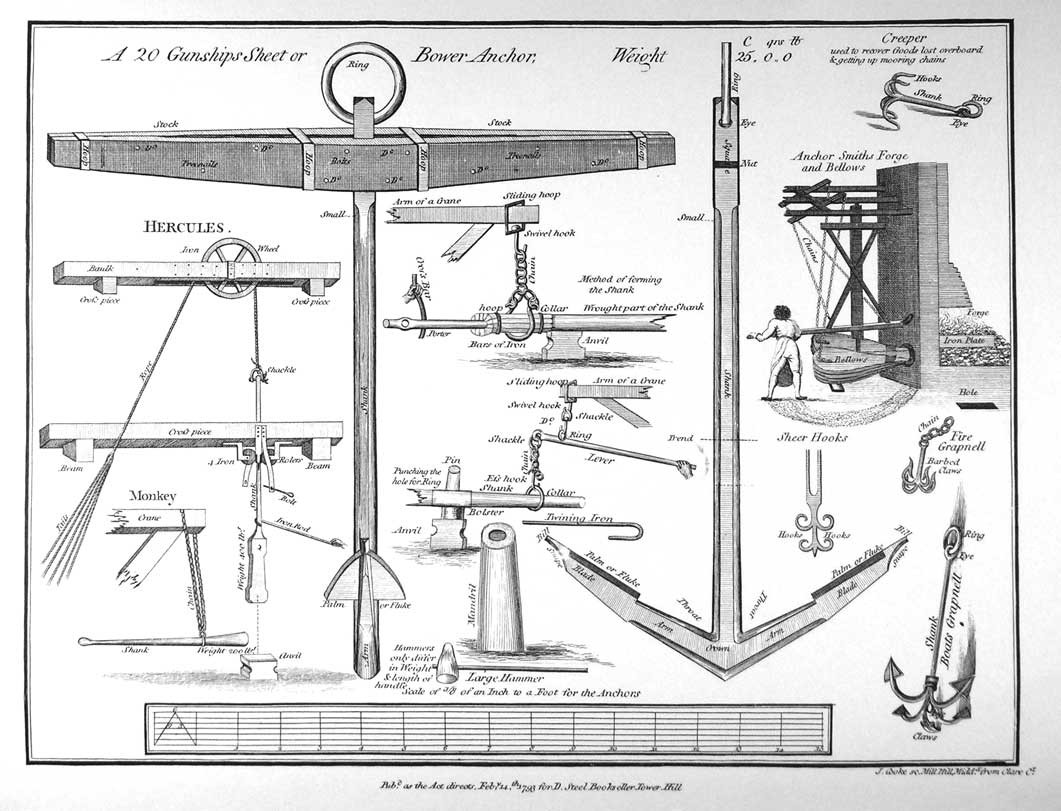

Technical drawings of a naval anchor, with the casting process illustrated to the right. While easier to manufacture than cannon, quality had to be ensured since ships relied on anchors for safety in all kinds of weather. Initially the navy contracted out anchor manufacturing, but by 1812 had established its own furnaces for the job. Today, a part of this museum stands on the navy yard’s original anchor furnace.

Pictured here are the tools of the block-maker’s trade. Block-making, a tedious but relatively well-paying job, provided each warship with the hundreds of blocks (pulleys to landsmen) needed to work the sails and guns. The navy yard’s block shop, located not far from where you’re standing, was burned in the 1814 fire during the British invasion.

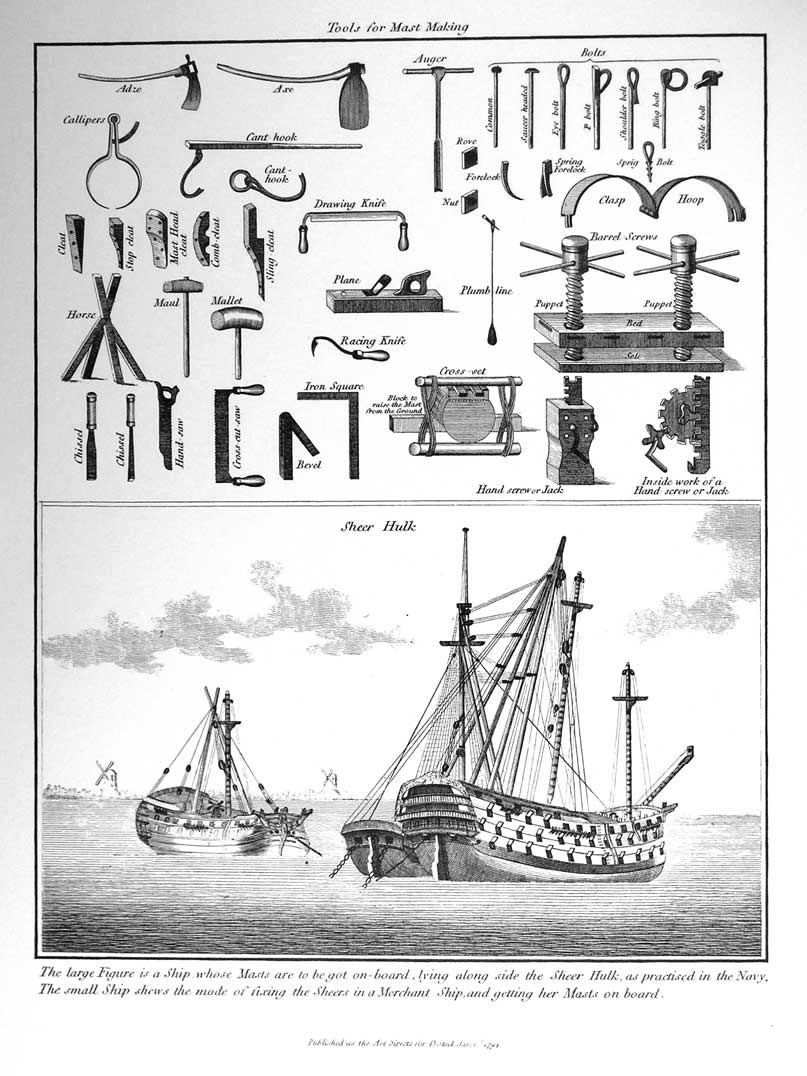

Top image: the various tools of the mast maker. Below image: a British man of war receiving new masts. By 1812, masts were made by fitting together many interlocking lengths of wood, planning and sanding them round, and securing it all with iron bands, a laborious early form of lamination. A year before the war, the Washington Navy Yard completely rebuilt and rearranged the masts of Wasp and Enterprise, two small navy vessels that went on to capture British warships.

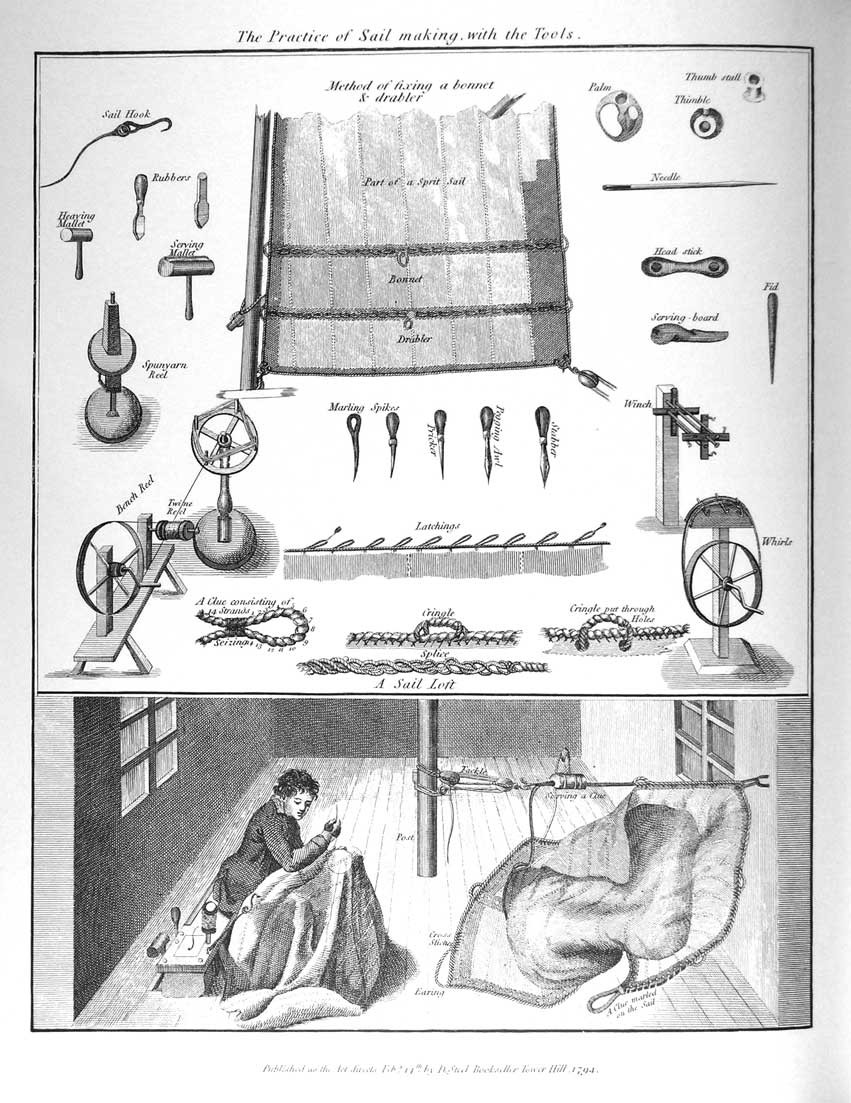

Sailmaking, a time consuming, highly skilled task, was still mainly done by hand in this period. By 1812 domestic flax sails were giving way to imported cotton, which held its shape and the wind better. Before the navy yards were fully established, the Boston Manufacturing Company was contracted to sew “one entire suit of sails” for the first six frigates, each of which had almost one acre of sail area.

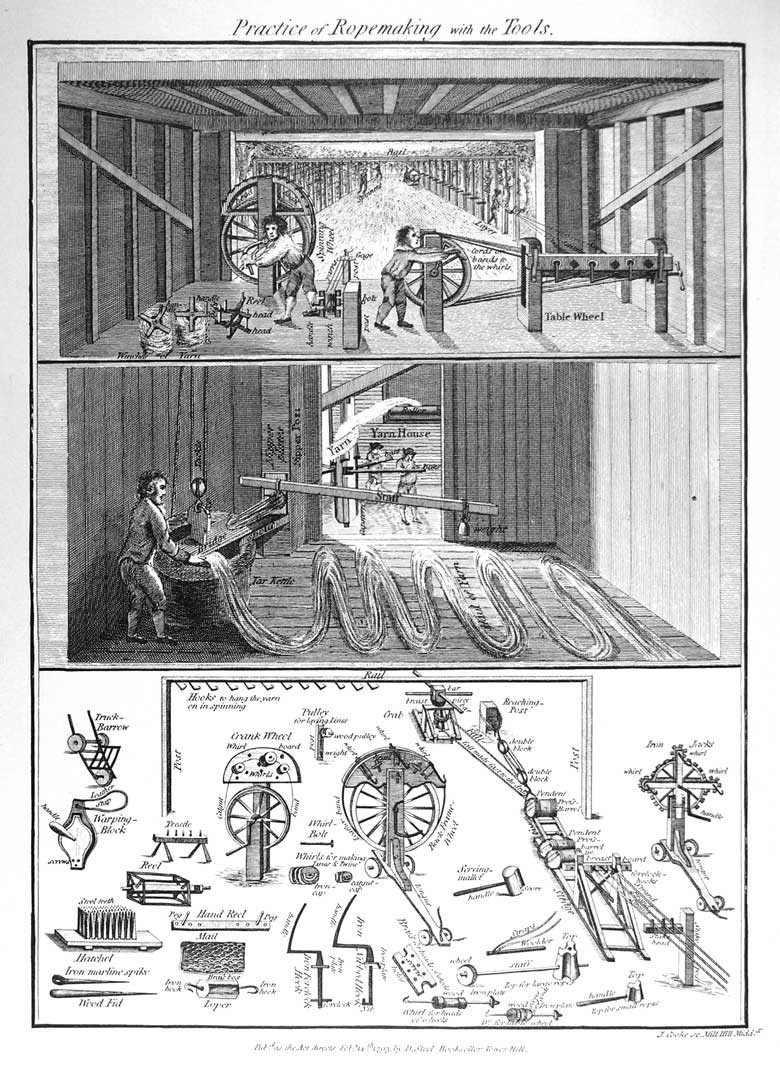

These images show the early industrialization of ropemaking. Rope was made in many diameters from half an inch to many inches. Early machines helped workers spin rope from hemp fibers. Imported Russian hemp was considered the best, because it was processed for water-resistance, but domestic Kentucky hemp supplied the U.S. Navy during the British blockade. USS Constitution alone required over 2 miles of rope for her running rigging and easily twice that length adding her standing rigging, anchor cables, and gun tackles.

Wartime Role of the Washington Navy Yard

…besides the new frigate, sloop of war, and several small vessels, at the navy yard there were large quantities of provisions and naval & military stores of all kinds…which ought to be destroyed in the event of the enemy getting possession of the City as those vessels provisions and Stores would be to him extremely important and valuable…

Memorandum of the Secretary of the Navy Jones, 24 August 1814.

Among the navy yards only Washington was fully operational by 1812; it was all Tingey could do to ready the ships going to war. The yard also strained to resupply the yards left inactive in the pre-war decade. Soon new warships were building there, but all were burned in 1814 to prevent their capture.

Guerriere Half-Model, Accession #62-124-S.

Half models were 19th century shipbuilders’ tool for converting small scale plans to full size ships. USS Guerrière, patterned after Constitution and named for the first British frigate taken in 1812, was launched June 1814, but saw no serious action during the war due to the blockade. A sister ship, USS Columbia, was among the vessels burned on the stocks at the Washington Navy Yard during the British invasion.

This artifact is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century area in Bldg. 76.

Careening Blocks, Accession # 46-389-C and # 46-389-D

These blocks and tackle were used to access the underside of ships’ before the U.S. constructed its first dry-docks. With their immense power, an unloaded and down-rigged ship could be “careened,” or rolled onto its side near the shore, allowing men to remove barnacles and weeds from its bottom, vital to a vessel’s upkeep, speed and maneuverability. With war in 1812, the Washington Navy Yard recommissioned some old frigates stored there, and would have careened the ships with such blocks before sending them to sea.

This artifact is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century area in Bldg. 76.

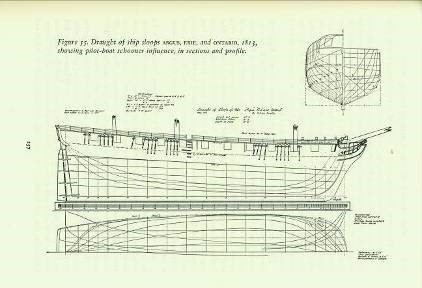

Hull for USS Argus. Chapelle, Howard I, The History of American Sailing Navy: The Ships and Their Development, No.150, Fig 55.

Despite early successes in 1812, the Navy recognized an urgent need to expand as Britain allocated more ships to the American war. Designed by William Doughty – Washington’s new naval constructor from Georgetown – Argus was an improved version of the famous sloops Wasp and Hornet, being somewhat larger, sleeker, and more powerfully armed. Laid down in 1813, she was burned incomplete on the stocks on August 24, 1814, to prevent her capture during the British invasion of Washington, but her sister ship went on to defeat HM Brig Reindeer that year.

Workforce of the Washington Navy Yard

We cannot affect with gratitude on that Supreme Being who has placed us in a land of Equal Rights and Liberty’s where the honest industry of the Mechanics is equally supported with splendor of the Wealthy.

Washington Navy Yard mechanics to President Thomas Jefferson, March 4, 1805.

Under Commodore Thomas Tingey, the Washington Navy Yard became one of the city’s largest employers of civilian craftsmen and labors, including: citizens, immigrants, freedmen, and slaves. Augmented by specialized contractors, these federal employees repaired or rebuilt nearly the entire navy by 1812.

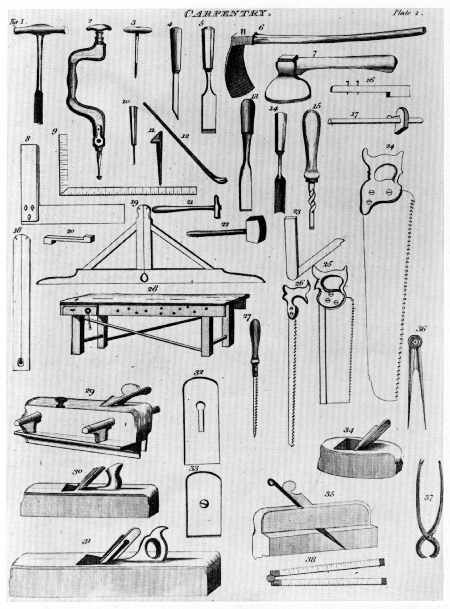

The Washington Navy Yard employed many specialist carpenters using tools like these, from a drawing circa 1813. Carpenters were classed by skill and trade, each class making between 1 and 2 dollars per day. Among yard workers, the most highly paid were shipwrights who fashioned the hull, while unskilled laborers were paid 75 cents per day.

In 1813 a certain class of carpenters at the Navy Yard petitioned Commodore Tingey for a raise in their daily wages. To answer an inquiry from the Secretary of the Navy, he drafted this report on the wages of his civilian employees. Unlike modern federal employees, most of his workers were paid a daily wage; only foremen were salaried. Although $1 to $2 per day seems little to us today, in 1812 this was competitive pay.

The Cost of a Navy

To ascertain the actual cost of building & equipping a frigate, we will take the actual cost of one of our largest viz the President – which was $220,910…we have heretofore estimated the annual cost of a frigate of 44 guns @ $110,000…

Secretary of the Navy Hamilton to the Chairman of the Naval Committee for the House.

The creation of the Navy was an undertaking of a new scale for the U.S., signaling a shift away from minimalistic national expenditure and a limited federal government. Despite the costs and rising debt, the Navy proved its worth: Congress approved massive expansion even as war was concluded.

Between its creation in 1794 and the outbreak of war, Navy spending annually averaged about 15% of the federal budget; during the War of 1812 this average topped half of all government spending, peaking at 73% in 1814, the highest for any American war. In the face of declining tariff revenues due to the British blockade, this wartime spending more than doubled the national debt, but with careful fiscal management was successfully paid off 20 years later.