Blue Water Operations: Part Three

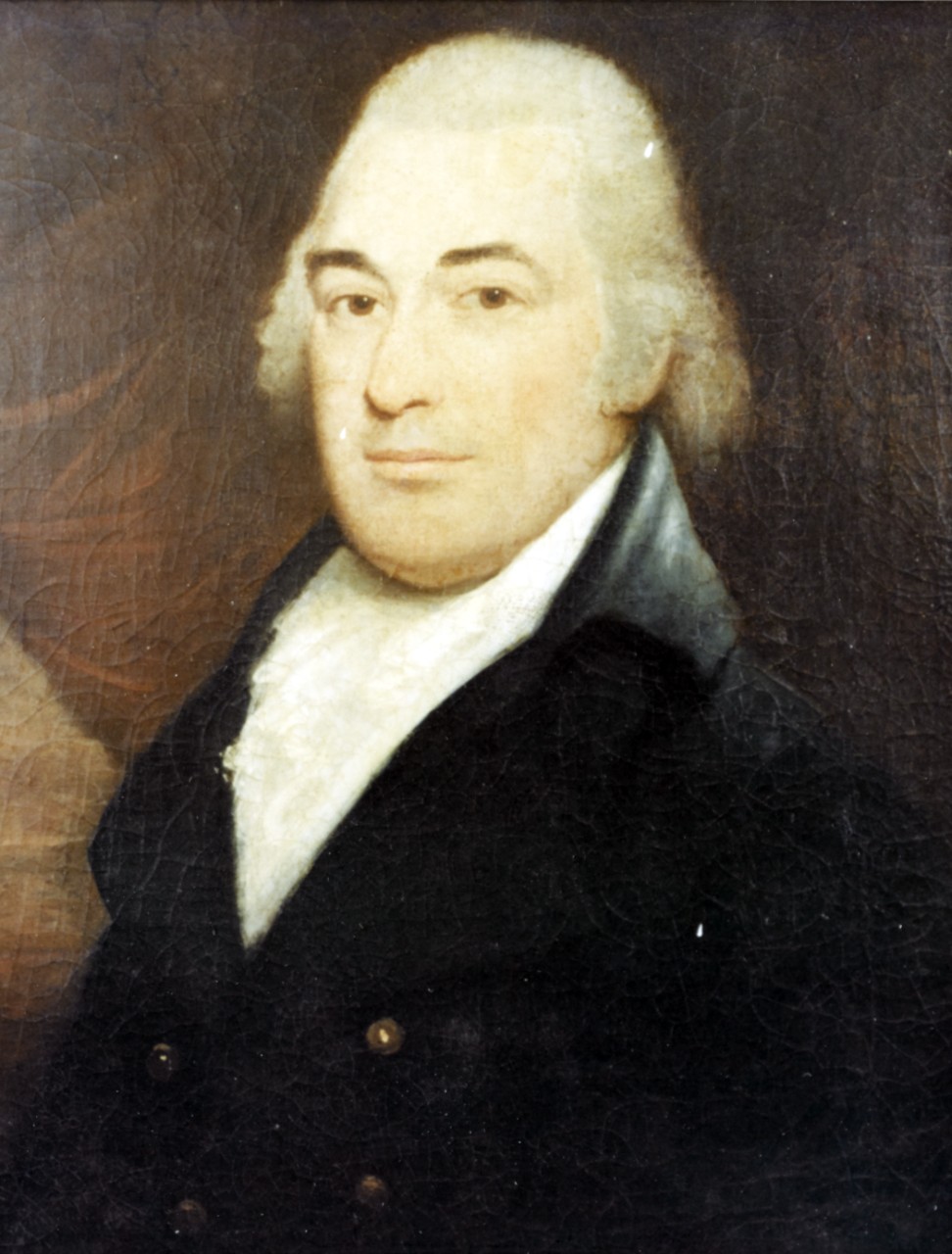

During the War of 1812, the position of Secretary of the Navy was filled by three different men who each had their own war strategies. Paul Hamilton (served May 1809-December 1812) ordered American vessels to patrol in squadrons with four or five other vessels. William Jones (served January 1813-December 1814) favored lone vessels, focused on destruction of British commerce. Benjamin Williams Crowninshield (served January 1815-September 1818) was more involved in peace negotiations than battle strategy.

Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Crowninshield. Artwork by U.D. Tenney. NHHC Photograph Collection, NH 54721-KN.

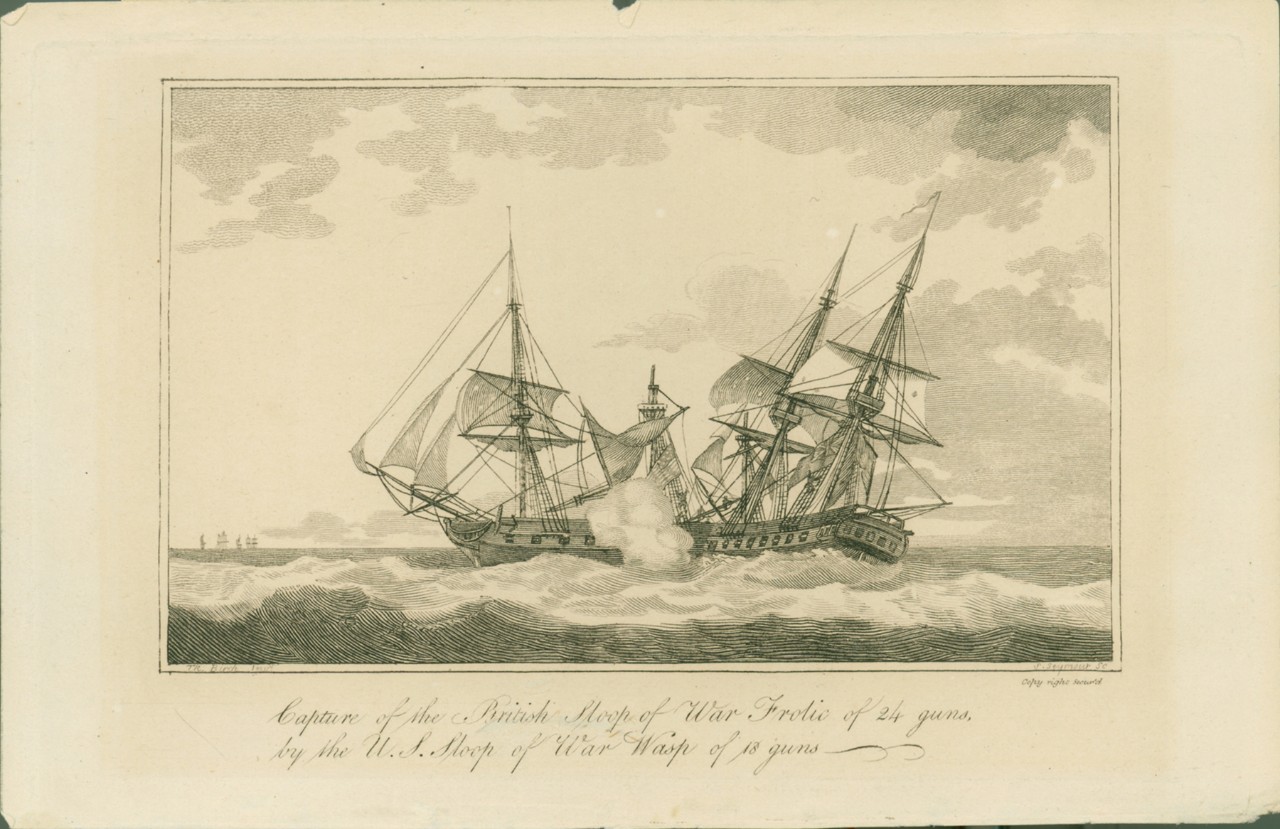

Wasp versus Frolic

The 18-gun sloop-of-war Wasp under Captain Jacob Jones fought and defeated the 20-gun brig Frolic on 18 October 1812. During the battle, Wasp lost a mast but was still able to rake and board Frolic. After the fight ended British 74-gun ship-of-the-line Poictiers arrived and took the Wasp, which could not escape with her rigging in such bad shape. She was destined to later become HMS Peacock.

Jacob Jones Medal. Accession #: 60-274-E.

These bronze medals are copies of one presented to Commodore Jacob Jones by Congress on January 29, 1813, for his victory in the action between the the sloop-of-war Wasp and HMS Frolic. Bronze medals like this one were given to libraries, and could be bought by private citizens after 1855. They were cast of the same mould as the original gold medal Jones received.

United States versus Macedonian

On October 25, 1812, the 44-gun frigate United States under the command of Stephen Decatur was sailing in the Eastern Atlantic when the crew spotted the 38-gun frigate HMS Macedonian. The two ships opened fired from a distance, the United States’ fire being more destructive, then they closed in on each other. The Macedonian suffered more than twice as many casualties and direct hits as the United States due to the more accurate American fire. The British surrendered and Macedonian became part of the American Navy; the only British frigate actually taken as a prize.

Stephen Dectaur Medal. Accession #: 60-274-F1.

This gold medal was awarded to Captain Stephen Decatur by Congress for the victory of United States over Macedonian. The face bears his likeness in profile, while the reverse depicts the frigate engagement.

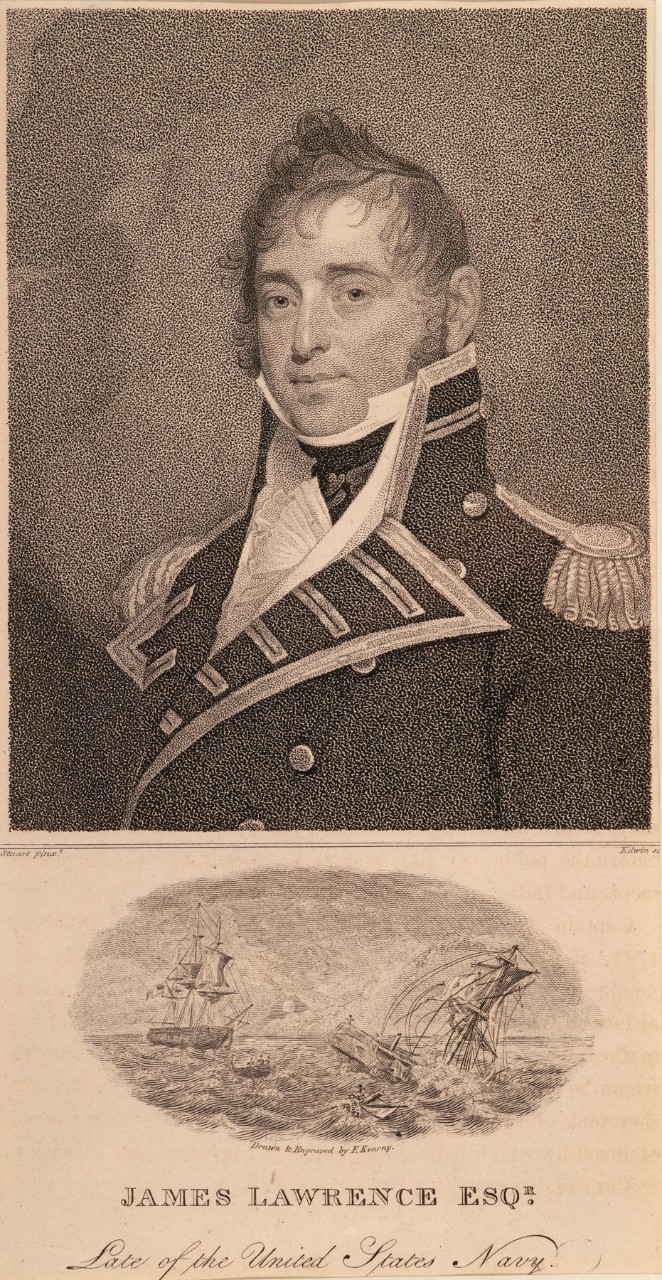

Chesapeake versus Shannon

On June 1, 1813, HMS Shannon and the frigate Chesapeake - both 38-gun frigates - met off the coast of Massachusetts just hours after Chesapeake left port with a new captain and crew. After 11 minutes of battle, the damaged Chesapeake collided with Shannon and the British captain, Philip Broke, led his veteran crew in boarding her. A small party of defenders wounded Broke, but was swept away, while aloft American topmen fired on enemies below until British sailors climbed through the rigging to silent them. Within four minutes of boarding the British were in control. That day, Chesapeake became the first American frigate lost to the British navy.

Captain James Lawrence commanded the frigate Chesapeake, in her engagement with HMS Shannon. Mortally wounded, his last instruction to the crew was, “Don’t give up the ship!” These words became a battle cry for Americans. Oliver Hazard Perry, commander of the American squadron on Lake Erie, named his flagship Lawrence, and sailed to victory over the British with James Lawrence’s famous words emblazoned on a flag.

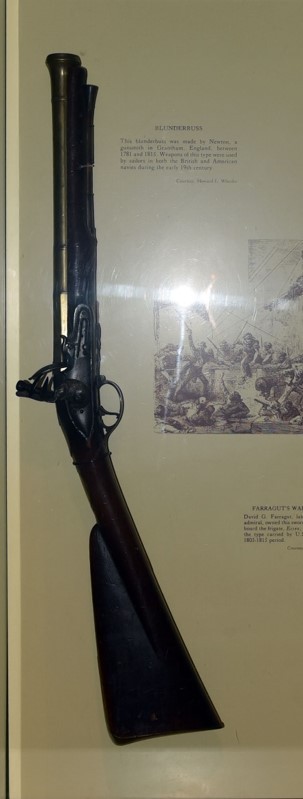

Aboard U.S. Navy vessels, small arms and edged weapons were normally lock away under the supervision of an officer; when they crew “beat to quarters”, these weapons were distributed as directed. One axe, a pike, a pistol and two cutlasses were given to members of each gun crew designated to act as boarders. These men would continue to man their guns until the captain called for boarders to assemble. Although decisive, boarding actions in the War of 1812 most often occurred after vessels unintentionally collided due to battle damage.

Blunderbuss. Accession #: 65-231-AD.

Blunderbuss

This blunderbuss was made by Mr. Newton, a gunsmith in Grantham, England sometime between 1781 and 1815. Weapons of this type were used by sailors in both British and American navies during the early 19th century. Guns like this were used like shotguns to fire a spread of small shot or musket balls.

Courtesy Howard L. Wheeler

This artfiact is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century exhibit in Bldg. 76.

U.S. Flintlock musket model 1795. Accession #: L94-184-A.

Flintlock Musket

This flintlock musket was based on the French Charleville pattern and was manufactured in the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts from 1797 through the War of 1812. This type of musket was the standard firearm for the Navy and Marine Corps during the War of 1812. During battle, marines and sailors in the fighting tops targeted enemy officers and gun crews using these muskets. Firing from their high vantage at ranges of less than 50 yards, these sharpshooters afforded the enemy below little cover; several British captains were killed by such fire during the War of 1812.

This artifact is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century exhibit in Bldg. 76.

British flintlock Pistol. Accession #: 69-31-W

British Flintlock Pistol

This .54 caliber flintlock pistol was made by John Sharpe in Birmingham, England about the year 1813. Unlike standard issue pistols it has a brass barrel to prevent rusting; such weapons were often bought by naval officers as personal side arms. Although they fired only one shot at a time and were accurate at no more than 25 yards, pistols were deadly in a tightly-packed boarding action. Those who could afford to generally carried several pistols since reloading was a dangerous distraction in a hand-to-hand fight.

This artifact is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century exhibit in Bldg. 76.

Oak Handled Boarding Axe. Accession #: 79-45-A.

Oak Handled Boarding Axe

This oak-handled boarding axe was made at the Washington Navy Yard between 1800 and 1810. Boarding axes were among the most valuable tools on a ship because they could serve as weapons, haul large coils of rope, chop fiery splinters from the ship, sever an enemy’s rigging or grapnels in close combat, and even cut loose fallen rigging aboard one’s own ship. One boarding axe was assigned to each gun crew for use in fighting fires or repelling enemy boarders.

James Lawrence Medal, Reverse. Accessions #: 60-274-L.

James Lawrence Treasury Medal

This medal is a bronze copy of the gold medal awarded posthumously to Captain James Lawrence by Congress for his capture of the British gun brig Peacock as captain of USS Hornet, and for his heroic example as captain when he lost the frigate Chesapeake to HMS Shannon. The original gold medal was presented to the nearest male relative of Captain Lawrence on January 11, 1814.

Essex versus Alert

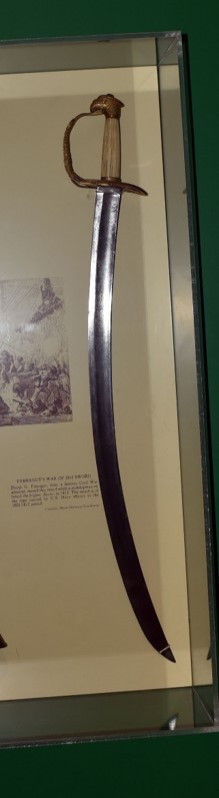

Midshipman Farragut’s War of 1812 sword. Accession #: 84-151-B.

Midshipman Farragut's War of 1812 Sword

Although the US Navy’s first Admiral, David Farragut, earned his fame during the Civil War, he began his naval career as a midshipman just two years before the War of 1812. He carried this sword while serving aboard the frigate Essex during her famous cruise in the Pacific in 1813. After Essex captured HMS Alert, 11 year-old Farragut heard the prisoners from the Alert planning to mutiny and take the Essex. Midshipman Farragut told Captain Porter and the mutiny was ended before it began. Farragut soon after received his first command, a British whaling ship, from among the frigate’s prizes.

This artifact is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century exhibit in Bldg. 76.

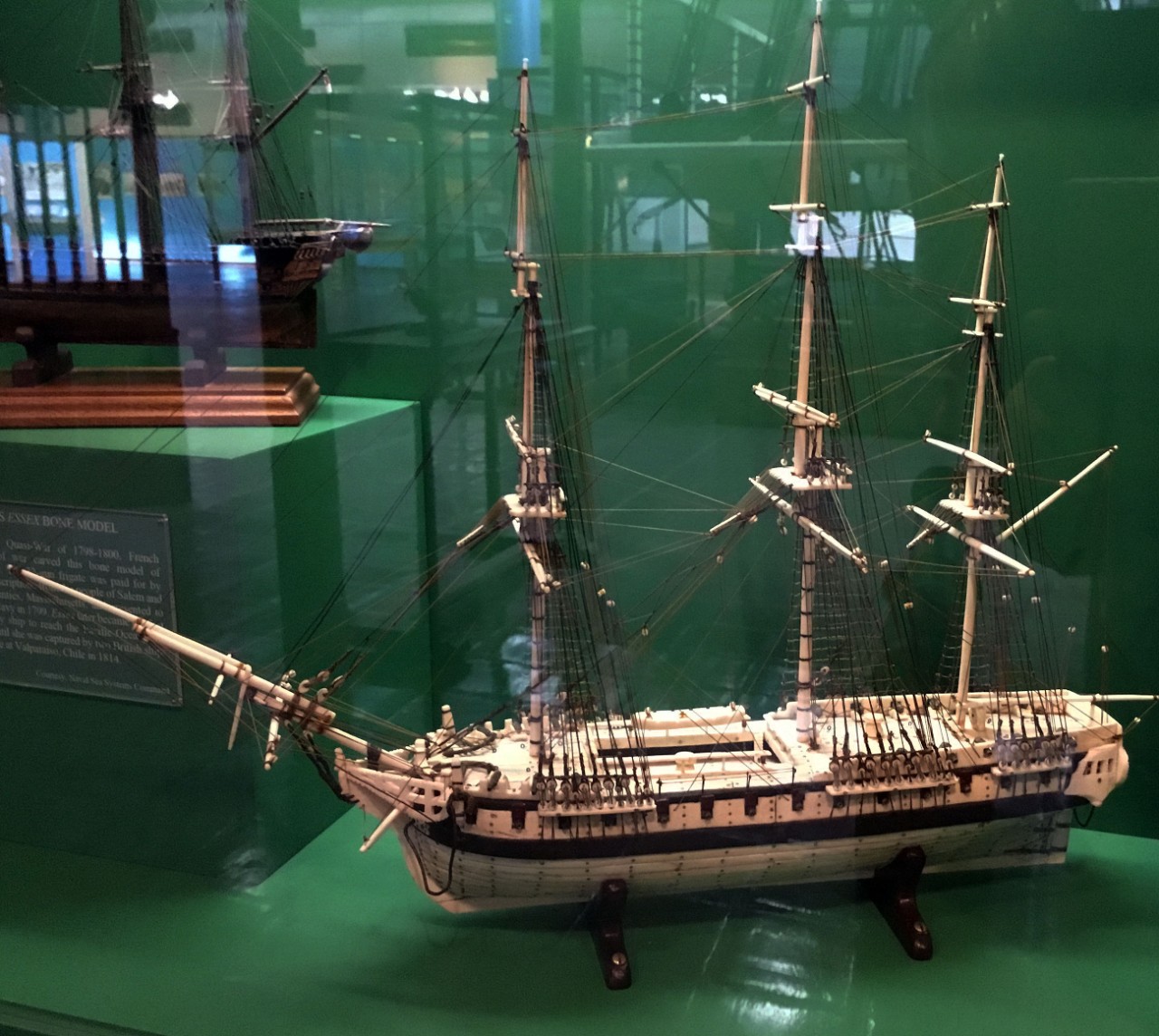

Bone Model of USS Essex. Accession #: 83-70-A.

USS Essex model

The people of Essex County and Salem, Massachusetts presented the 36-gun frigate Essex to the US Navy in 1799. Within weeks she began active service and fought in the Quasi War with France, the Barbary Wars, and the War of 1812. This bone model was made by a French prisoner of war during the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century.

This model is on display in The Forgotten Wars of the 19th Century exhibit in Bldg. 76.

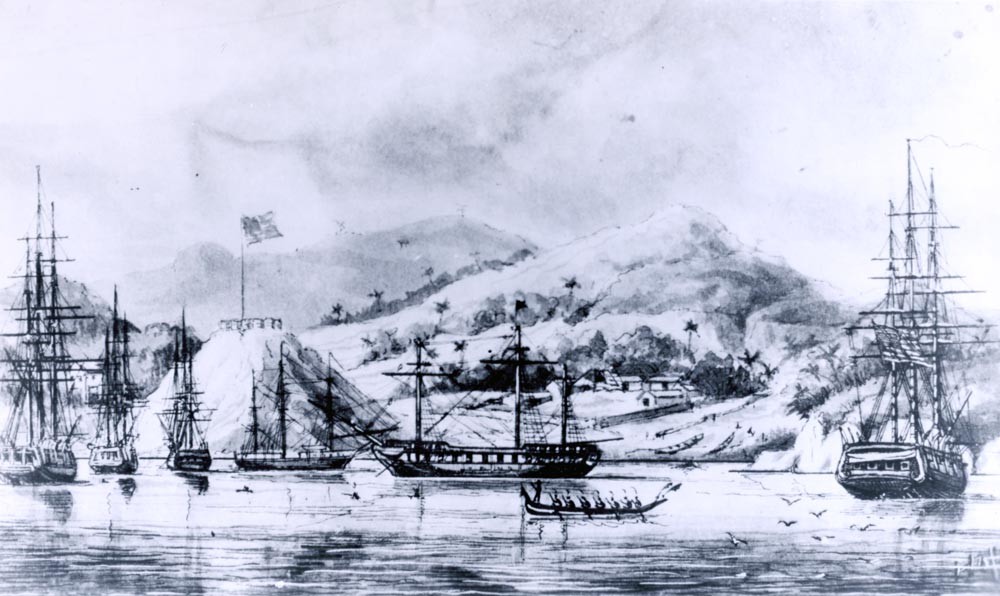

Frigate Essex in the Pacific. NHHC Photograph Collection, NH 66425.

On 28 October 1812 the frigate Essex, under the command of Captain David Porter, began an eighteen month cruise into the Pacific Ocean – the first U.S. warship to venture there - to attack the British whaling fleet. During this cruise, the Essex captured fifteen British vessels and caused 2.5 million dollars worth of damage to the British whaling industry.

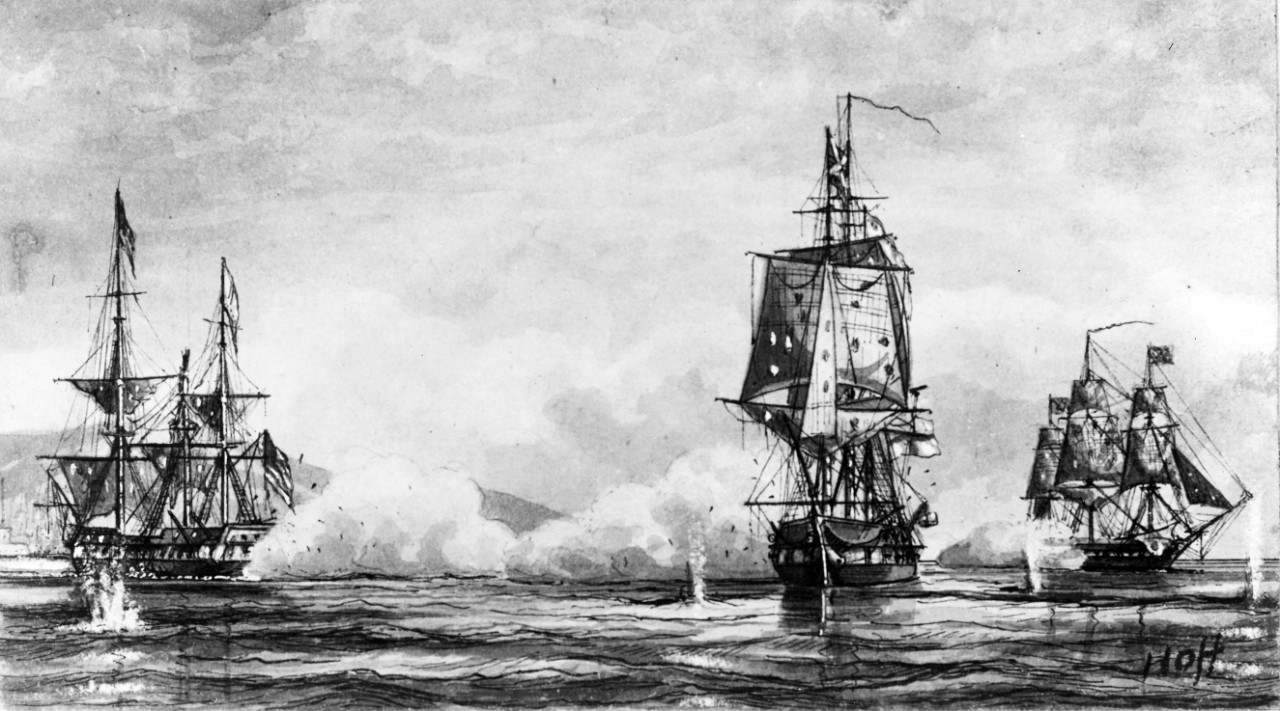

Frigate Essex versus HMS Cherub and HMS Phoebe. NHHC Photograph Collection, NH 1528.

On January 12, 1814, 32-gun frigate Essex entered Valparaiso Bay in Chile – neutral territory where she expected to find refuge – and was blockaded there for several months by the 36-gun frigate HMS Phoebe and the 18-gun sloop-of-war HMS Cherub. On March 28, 1814, Essex made for sea but lost her main top mast in a squall. Thus crippled, the British vessels intercepted her, and took firing positions at a distance. Armed primarily with short-ranged carronades – a novel armament for a ship of her size – Essex could only reply with a few long guns. Nonetheless, she caused significant damage to her opponents. After fighting for two and a half hours and suffering nearly 60% casualties, Essex surrendered. The British kept the Essex until auctioning her off in 1837.