Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Drewry's Bluff

Virginia

15 May 1862

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP

Commander John Rodgers, United States Navy (USN)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP

Commander Ebenezer Farrand, Confederate States Navy (CSN)

Captain Augustus Drewry, Confederate States Army (CSA)

BACKGROUND

In April 1861, the Virginia Convention of 1861 reversed its vote against secession after a series of events shifted popular opinion in the state. The convention subsequently voted to adopt the constitution of the Confederate States of America. In May 1861, the Confederate Congress voted to move their capital from Montgomery, Alabama, to Richmond, Virginia. Their army began preparing fortifications surrounding the new capital. The work was slow and the congress became nervous as winter turned to spring. On 24 February 1862, the congress called for a survey of Richmond’s defenses. The situation unfolding at Hampton Roads presented more than one threat to the security of the Confederate capital.

The acting chief engineer, Major Alfred Rives, was responsible for the survey of the city’s defenses. On 12 March, just days after the naval battle of the ironclads at Hampton Roads, he presented his progress to the Confederate Congress. Work had already begun in earnest to extend the line of fortifications south of the city. Confederate engineers identified a high bluff on the south side of the James River eight miles south of Richmond as the best side to guard the water approach to the capital. The site overlooked a narrow stretch of the James River. Although Rives was confident of the strength of the position, he was less sure of the strength of any fortification in a contest with an ironclad. [1]

Rives was not the only one who was worried about the effect that ironclad technology was having on how naval battles were fought. Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall, CSN, had assumed command of CSS Virginia after the battle on 9 March 1892. He felt that his government was putting too much emphasis on one ship’s ability to defend Hampton Roads. He attempted to correct the misconception that he could challenge the enemy fleet at Hampton Roads directly. The U.S. Navy fleet was at anchor in the Chesapeake Bay under the protection of the forts that guarded the roads. Tattnall did not want to risk losing the only ship guarding Norfolk and its shipyard.[2] The same armor and heavy ram that made Virginia a formidable enemy to Monitor also inhibited its maneuverability and its ability to stay afloat in open sea. These failings, combined with its deep draft, trapped Virginia in the same waters that it was built to defend.

After the battle between Virginia and Monitor, uncertainty festered in Hampton Roads. Another engagement could decide everything, but both sides knew their limitations and refused to give the advantage to the enemy. Stephen Mallory, the Confederate secretary of the Navy, put his hopes for the future of his Confederate Navy on Virginia. Others were not as confident. Tattnall warned Mallory that the presence of Virginia at Norfolk did not mean that the enemy could not ascend the James River.

Commander John R. Tucker, the commanding officer of CSS Patrick Henry (formerly USS Yorktown) and the commander of the Confederacy’s James River Squadron, shared Tattnall’s concerns. Assigned to Mulberry Point on the James River, Tucker’s squadron guarded the right flank of General John Magruder’s Army of the Peninsula. Tucker knew his squadron’s limitations, giving ready warning that his force would not be able to hold their position against ironclad vessels or larger wooden men-of-war.[3] This squadron was poised for retreat in the face of an enemy navy that outnumbered and outgunned them.

PRELUDE

Throughout March and April 1862, the combined forces of the Confederacy continued to fortify their positions closer to Richmond. In 17 March 1862, an artillery unit under command of the local landowner, Captain Augustus H. Drewry, CSA, began mounting guns at the newly constructed Fort Darling (Drewry’s Bluff) overlooking the James River. Commander Richard L. Page, CSN, supervised the sinking of several vessels at in the river to impede any Federal advance beyond the bend. This point was the best chance for the Confederacy’s combined forces to protect the waterways on the path to their capital.

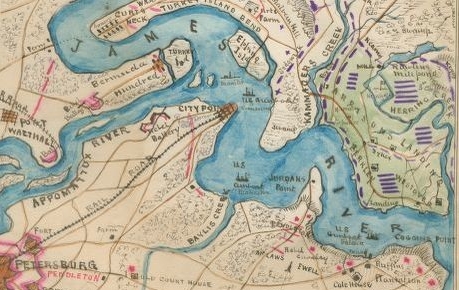

The Chesapeake Bay, the James River, the York River, and Hampton Roads bound the Virginia Peninsula in southeastern Virginia. General-in-Chief George McClellan originally conceived the Federal campaign for the spring of 1862 in late January 1862. He proposed an amphibious landing at Urbanna on the Rappahannock River that would flank the Confederate forces arrayed near Manassas and separate them from Richmond. However, McClellan waited too long to launch his campaign. Four weeks after McClellan presented his plan to Lincoln, a shift by the opposing forces to Fredericksburg forced McClellan to change his plans. He rerouted his troops to Fort Monroe, in Hampton, Virginia. This fort had remained under the control of the U.S. Army even after the loss of Norfolk and Gosport Navy Yard. This foothold on the tip of the peninsula was to be McClellan’s launch point for an 80-mile march on Richmond. Unfortunately, the original plan was a flank attack designed to turn the enemy lines. This new plan put McClellan front-to-front with his enemy. Magruder’s army was already entrenched across the peninsula along the Warwick River, blocking the path to Richmond.

The battle of the ironclads in March 1862 further hindered McClellan’s plans.[4] He needed the Navy to move his troops from Alexandria to Hampton. He knew that the cooperation of the Navy was essential to his success.[5] McClellan considered changing his plans again after the showdown between Virginia and Monitor.[6] While McClellan hesitated yet again, Lincoln did not. He removed McClellan as general-in-chief of the U.S. Army, although retaining him as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln became his own general-in-chief until the appointment of Henry W. Halleck in July 1862. McClellan had no more time to waste regardless of changing plans and enemy ironclads.

On 17 March, McClellan sent his first contingent to Fort Monroe. He expected the full cooperation of the U.S. Navy.[7] As commander of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron based at Hampton Roads, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough was the naval officer responsible for cooperating directly with McClellan’s army. Magruder had established a strong line of defense along the Warwick River. With the entrance to the James River blocked by the combined strength of Virginia and the James River Squadron, the York River offered the only riverine route to open the navigation of a river in the direction of Richmond.

Goldsborough sent gunboats to assist the army in reducing the Yorktown and Gloucester Point batteries.[8] Although Virginia remained at large, he was confident that the vessel could not ascend the York River.[9] On 4 April, Goldsborough assigned Commander John Missroon, of Wachusett, to lead a flotilla that also included: Penobscot, Marblehead, Corwin, Octorara, Victoria, and Currituck.

On 5 April, McClellan completed landing his army at Fort Monroe and began his advance toward Yorktown. After encountering enemy resistance along the Warwick River, McClellan became convinced that he was outnumbered despite evidence to the contrary. [10] He laid siege to Yorktown while awaiting reinforcements.[11] The Army of Potomac remained immobile for the next four weeks.

Goldsborough was reluctant to leave Virginia unopposed at Hampton Roads. McClellan had to make do with Missroon’s flotilla. Goldsborough gave permission for Missroon to do whatever he felt possible to support McClellan’s advance and it seemed that Missroon was willing to do whatever was necessary at the start of the campaign.[12] However, it soon became clear that these intentions fell short. Any attempt to coordinate the movement of the army with an attack by the gunboats failed.[13] Missroon’s flotilla of light gunboats remained ready to defend the army transports against enemy steamers in the area, but he was unwilling to confront the enemy batteries along the river.[14]

On 11 April, Virginia made a second appearance near Newport News, but it did not attempt to engage the Federal fleet under the guns of Fort Monroe. Goldsborough encouraged the immediate deployment of the recently commissioned ironclad Galena. McClellan was aware of the new ironclads under construction. He wrote to Gustavus Fox, the Assistant Secretary of the Navy, asking about the status of Galena. He seemed convinced that this new ironclad might determine the success of his operations.[15] As the siege continued, Fox shared concerns with Goldsborough that the public was putting blame for its lack of resolution on the Navy. The service was faulted for failing to support McClellan.[16]

On 2 May, Magruder’s army abandoned their works and withdrew toward Richmond. In evaluating the works on 3 May, Fox determined that if Missroon had pushed past the batteries, then “the Navy would have had the credit of driving the army of the rebels out.” Fox was disappointed in Goldsborough’s failure to break the siege at Yorktown. [17]

The James River Squadron covered Johnston’s retreat while Virginia alone stood guard at Hampton Roads.[18] Johnston continued to fall back toward Richmond to a new line of defense on the Chickahominy River.[19] McClellan requested Galena and the other gunboats to ascend the waterways toward Richmond.[20] Under orders from Lincoln, Welles finally ordered Goldsborough to send the ironclad Galena, accompanied by two gunboats, up the James River.[21] On the morning of 8 May, Commander John Rodgers, of Galena, led Aroostook and Port Royal up the James River. Rodgers reported a delay after his vessel ran aground near Jamestown Island, but they had no opposition as they resumed their ascent.[22] The James River Squadron did not stop their withdrawal until they reached Drewry’s Bluff.

On 9 May, the Confederate forces in Norfolk received orders to destroy the navy yard and evacuate to Richmond. The withdrawal of Magruder’s army had left the forces at Norfolk isolated. They delayed their evacuation long enough to launch their unfinished ironclad, Richmond, and tow the vessel to the Confederate capital. The combined services of the U.S. government had recaptured Norfolk, Portsmouth, and the Gosport Navy Yard without a battle.

Unable to escape Hampton Roads and unable to retreat up the James River, Confederate sailors scuttled Virginia on 11 May.[23] The crew of the ironclad were reassigned to Drewry’s Bluff. A former officer aboard Virginia, Lieutenant John T. Wood grieved that “[T]he Navy for the time has been destroyed & we must seek other ways of rendering ourselves useful.”[24] Commander Tucker docked his flagship, Patrick Henry, and the other remaining vessels of the James River Squadron beyond the barrier. The fleet prepared to fight if the Federal gunboats were to get past the scuttled Virginia, but the battery at Fort Darling was the first line of defense.

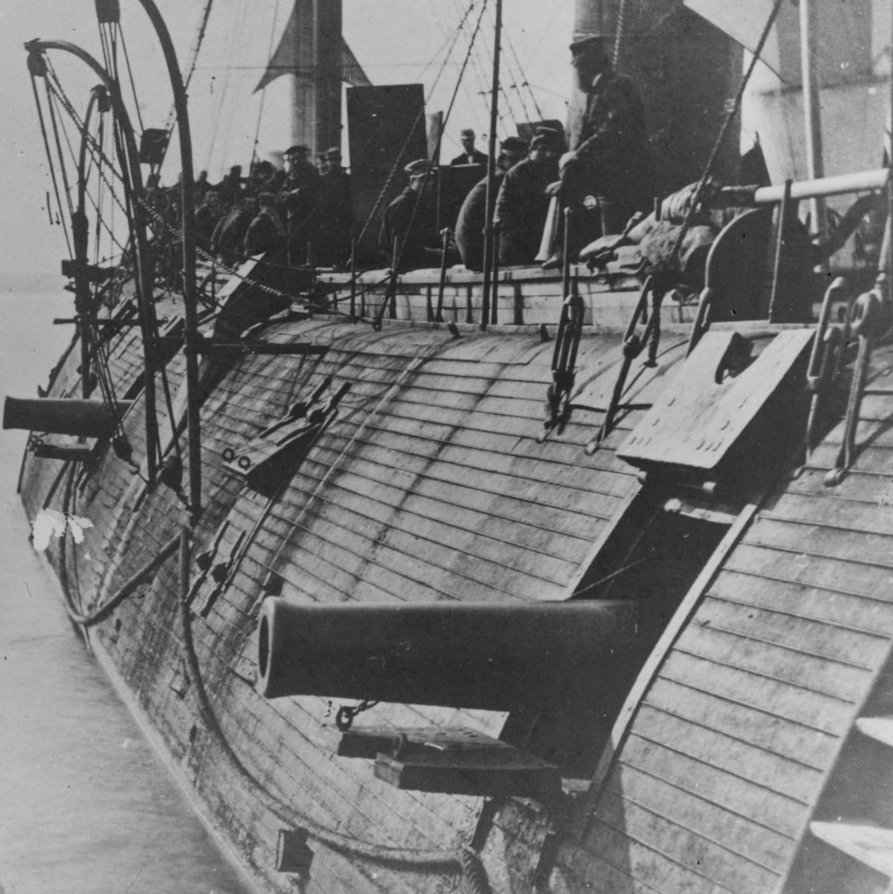

Commander Ebenezer Farrand, of the Confederate Navy, was in command at Fort Darling. Captain Augustus Drewry’s artillery regiment mounted three large seacoast smoothbore guns—one 10-inch and two 8-inch columbiads—overlooking the river on his own land. Their position gave these guns a range of approximately one to two miles in each direction depending on the angle of elevation.[25] Five more naval guns—four of them rifled—were removed from the vessels of the James River Squadron and placed along the bluff. The Confederate sailors sunk Jamestown alongside other vessels to fortify the barrier in the river. With all of these preparations, the citizens of Richmond still worried that these defenses along the James River would prove insufficient to protect them from the enemy ironclads.[26]

On 12 May, Monitor accompanied by the U.S. Revenue steamer E. A. Stevens (Naugatuck) left Norfolk to rendezvous with Galena, Aroostook, and Port Royal at Jamestown Island.[27] On the following day, they reached City Point. Leaving City Point the next day, Stevens continued ahead to sound out the channel. The steamer came within three miles of Fort Darling before anchoring for the night.

BATTLE

At 0630 on 15 May 1862, the ironclads–Monitor and Galena–came in sight of Drewry’s Bluff. The ironclads were accompanied by two wooden gunboats—Port Royal and Aroostook—and Naugatuck. As the flotilla approached, they came under fire from the barrier below the bluff. Unwilling to retreat and unable to bypass the fort, the Federal fleet positioned themselves a half a mile below the barrier and proceeded to take aim on the fort. [28] Confederate sharpshooters along the banks of the river contributed to the casualties inflected on the Federal gunboats, but it was the battery above that did the most damage to the fleet. With little room to maneuver in the narrow channel, the vessels could do little to avoid damages or casualties. The steep incline of the bluff both inhibited the firepower of the ironclads and exposed the lightly plated decks to the enemy. The combined forces of the Confederate garrison took aim at the stationary targets.

The Confederate cannons remained trained on Galena as its broadside presented the largest target. This was the first test of the new ironclad. It was hit 28 times. All but ten of those hits perforated its armor. Before noon, Galena was out of ammunition. Thirteen men were killed, and 11 wounded on board Galena alone. [29]

The James River was open to navigation by U.S. Navy below Drewry’s Bluff. Rodgers withdrew his vessels to City Point to await cooperation with the army. The battle itself was less than three hours from the firing of the first shots. The casualties in this battle totaled 41 on both sides. The Confederate garrison suffered few casualties compared to the attacking fleet.[30]

AFTERMATH

The Confederate naval forces at Drewry’s Bluff had successfully repulsed the Federal fleet. With this victory, a contingent of Confederate sailors were permanently attached to the fort. Despite this success, Farrand was to be replaced right after the battle that earned him accolades. Mallory ordered Captain Smith Lee, Robert E. Lee’s brother, to relieve Farrand of his command. This transfer of authority was meant to ensure the continuing cooperation of the land and naval forces associated with this command.[31]

From his anchorage in City Point, Rodgers made it clear that he was willing to cooperate in a renewed advance on Petersburg when the army was ready.[32] Lieutenant William Jeffers, of Monitor, agreed that “[i]t was impossible to reduce such works except by the aid of land force.”[33] With these reports from his subordinates, Goldsborough asserted “without the Army, the Navy can make no real headway towards Richmond.” The Navy did not intend another singlehanded attempt to extend navigation of the James River past Drewry’s Bluff. Although there were sailors on the gun crews on both sides, the battle at Drewry’s Bluff was a battle between ship and shore. Without cooperation from a land force, the Federal flotilla had no advantage against this heavily fortified position. There would be no coordinated effort to take Drewry’s Bluff in 1862. By July, McClellan was in retreat toward the James River after the Seven Days Battles. Rodgers’ flotilla covered McClellan’s withdrawal to Harrison’s Landing on the James River.[34]

In July, Fox and Welles decided a change in leadership was necessary. The relationship between McClellan and Goldsborough had become more strained during this campaign. The Navy organized the gunboats in the James River into an independent command, the James River Flotilla. Rather than retaining Rodgers as its commander, Fox and Welles appointed Charles Wilkes. The establishment of this independent command and Wilkes’ appointment later drove Goldsborough to resign his command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron.[35]

In late July, Henry W. Halleck took command of the armies of the United States. Although McClellan continued to retain his command of the Army of the Potomac, Halleck soon ordered it back to Washington. The new flotilla shielded the withdrawal of the army back down the peninsula. On 28 August, the flotilla left its anchorage at Harrison’s Landing and moved back down the river.[36] The Federal recapture of Norfolk and its shipyard was ultimately the most significant gain for the U.S. forces in this campaign. The York and James rivers were now open to navigation by U.S. Navy.

The Confederate garrison at Drewry’s Bluff saw action again in 1864. General Benjamin Butler landed the Army of the James at Bermuda Hundred, 15 miles south of Richmond, and marched to Drewry’s Bluff. The Navy failed to support his assault, which did not succeed. The garrison at Drewry’s Bluff did not abandon its post until after the fall of Richmond in April 1865.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

Navy Civil War Chronology, 1862

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Richmond National Battlefield Park. Drewry’s Bluff. National Park Service.

Bailey, Roger A. Steel & Steam: Naval Technology in the Civil War Era. American Battlefield Trust.

McFarland, Kenneth M. The James River during the Civil War. Encyclopedia Virginia.

FURTHER READING

Browning, Robert M., Jr. From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War. Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Coski, John M. Capital Navy: the Men, Ships, and Operations of the James River Squadron. Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 1996.

Hayes, John D. “Fleet Against Fort.” Ordnance 45, no. 243 (1960): 357–60.

Sears, Stephen W. To the Gates of Richmond: the Peninsula Campaign. New York: Ticknor & Fields, 1992.

Symonds, Craig. Union Combined Operations in the Civil War. New York: Fordham University Press, 2010.

***

NOTES

[1] United States War Department, The War Of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (ORA), Series 1, vol. 51, pt.2 (Washington: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1897), 509.

[2] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (ORN), Series 1, vol. 7 (Washington: GPO, 1898), 769–70.

[3] ORN, 1, 7:776.

[4] Robert M. Browning, Jr., “Defunct Strategy and Divergent Goals: The Role of the United States Navy along the Eastern Seaboard during the Civil War,” Prologue Magazine 33, no. 3 (Fall 2001).

[5] ORA, 1, 5 (1881):58.

[6] ORN, 1, 7:75.

[7] ORN, 1, 7:191, 196.

[8] ORN, 1, 7:199–200.

[9] Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (JCR), Pt. 1 (Washington: GPO, 1863), 631.

[10] JCR, 1:360.

[11] ORN, 1, 7:205.

[12] ORN, 1, 7:206–7.

[13] ORN, 1, 7:210.

[14] ORN, 1, 7:210; ORN, 1, 7:226; ORN, 1, 7:231.

[15] ORA, 1, 11, pt. 3 (1884):115.

[16] ORN, 1, 7:250.

[17] ORN, 1, 7:327.

[18] ORN, 1, 7:785.

[19] ORN, 1, 7:313.

[20] ORA, 1, 11(pt. 3):146.

[21] ORN, 1, 7:327–28; Craig Symonds, Lincoln and his Admirals (Oxford: Oxford University Pres, 2010), 153.

[22] ORN, 1, 7:332.

[23] Tattnall was later called before a court of inquiry for his decision, although he was acquitted. ORN, 1, 7:790–99.

[24] John Taylor to wife, 24 May 1862, John Taylor Wood Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC in John M. Coski, Capital Navy: the Men, Ships, and Operations of the James River Squadron (Campbell, CA: Savas Woodbury Publishers, 1996), 42.

[25] Albert Manucy, Artillery Through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasizing Types Used in America National Park Service Interpretive Series. History, no. 3 (Reprint, Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1985), 51–52.

[26] Daily Dispatch, Richmond, VA, 2.

[27] ORN, 1, 7:368.

[28] ORN, 1, 7:362.

[29] ORN, 1, 7:366–69.

[30] ORN, 1, 7:369.

[31] ORN, 1, 7:800–1.

[32] ORN, 1, 7:358.

[33] ORN, 1, 7:362.

[34] Robert M. Browning Jr, From Cape Charles to Cape Fear: the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron during the Civil War (Tuscaloosa and London: University of Alabama Press, 1993), 56–57.

[35]ORN, 1, 7:548; ORN, 1, 7:573–4.

[36] ORN, 1, 7:803.