Civil War Naval Operations and Engagements:

Hatteras Inlet

North Carolina

28-29 August 1861

FEDERAL LEADERSHIP:

Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, United States Navy (USN)

General Benjamin F. Butler, United States Army (USA)

CONFEDERATE LEADERSHIP:

Commodore Samuel Barron, Confederate States Navy (CSN)

in command of defense of Virginia and North Carolina

Colonel William F. Martin, Confederate States Army (CSA)

in command of Seventh North Carolina Volunteers

Major W. S. G. Andrews, in command of Forts Clark and Hatteras

BACKGROUND

Following the fall of Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln declared a blockade of all ports in the seven seceded states of the Confederacy. During the first months of the war that followed, blockade-runners and Confederate privateers, privately owned ships authorized by their government to attack U.S.-based merchant vessels, often sought shelter in the shallow estuaries on the coast of North Carolina.[1] The Confederate government was less interested in the stolen cargo than the distraction that the privateers presented to their opponent. Pamlico Sound is the largest sound on the eastern coast of the United States. Hatteras Inlet is one of three passageways that connect Pamlico Sound with the Atlantic Ocean. The U.S. Navy quickly recognized the strategic importance of Hatteras Inlet as the main channel into Pamlico Sound.

Neither of the earthen forts built to protect the inlet existed before 1861. Governor John W. Ellis of North Carolina ordered their construction in the first month after the start of the war. After the fall of Fort Sumter, Governor Ellis opposed the call to arms from U.S. President Abraham Lincoln before his state legislature had declared their vote for secession. He declared to the U.S. Secretary of War Simon Cameron that “You can get no troops from North Carolina.”[2] Confederate Secretary of War L. P. Walker requested troops from Governor Ellis before the state of North Carolina formally seceded from the Union.[3] The governor agreed with the stipulation that he needed funds for the transportation of state troops because he lacked the authorization to send troops using such monies funds until the legislature had made their final decision.[4]

Governor Ellis then ordered state troops to seize all federal forts in North Carolina.[5] With the goal of building new coastal fortifications along the Outer Banks, Ellis requested an engineer and artillery officers from the new president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, who quickly granted his request.[6] This series of events prompted Lincoln to extend the blockade of the Atlantic coast to North Carolina before the end of April. On 1 May 1861, Governor Ellis reported to Davis that the state legislature had voted to allow the deployment of state troops.[7] Concerned about U.S. Navy ships on the coast near Cape Fear, Governor Ellis sent North Carolina state troops to begin preparing coastal defenses for war while he waited for North Carolina legislature to cast their vote for secession.[8]

PRELUDE

The local tax collector at the Port of Hatteras, John W. Rollinson, documented the arrival of state troops on the island on 9 May 1861.[9] Eleven days later, North Carolina legislature officially voted for secession. U.S. Army Brigadier General Walter Gwynn resigned his command in Norfolk to take charge of the new Northern Department of the Coast Defenses in North Carolina. He oversaw the construction and armament of the new batteries on the Outer Banks from aboard the steamer Stag. Colonel Ellwood Morris, the engineer sent by Jefferson Davis, designed the two earthen forts at Hatteras Inlet. They were less than a mile apart. Colonel Morris designed Fort Clark to face the ocean and Fort Hatteras to face the inlet, both on the same side of the channel. After Governor Ellis of North Carolina died in July, Henry Toole Clark became the new governor of North Carolina.

On 2 August, Major W.S.G. Andrews, CSA, in command of the garrisons at the new forts at Hatteras, wrote to the new governor of North Carolina of his concerns in his new post. Andrews was worried that the increasing success of the Confederate privateers spelled trouble for his command.[10] He had good reason to be concerned. The victims of the Confederate privateers regularly reported their losses to the Department of the Navy beginning in May 1861. The U.S. Navy captains responsible for the blockade had noticed the use of Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds as refuges for Confederate privateers. Secretary Welles planned to shut down these safe havens along the eastern seaboard, and these reports gave him good reason to prioritize an attack on the coast of North Carolina.[11]

In May 1861, Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham reported to Hampton Roads as the new commander of the Coast Blockading Squadron, soon to be renamed the Atlantic Blockading Squadron. With 14 ships and the Potomac River Flotilla in his new squadron, Stringham made numerous requests in the next two months for additional vessels. In July 1861, Stringham positioned Roanoke, Albatross, and Daylight off the coast of North Carolina, but he took no further action until August.[12]

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles understood the need for swift and effective movement in establishing this blockade, but he lacked the numbers. In April 1861, he had only 12 ships out of the 42 ships then in service of the Navy available for this task. In the short term, Welles and his administration worked to recall ships stationed overseas and procure new ships; however, he needed a solid advisory board to think about long-term goals. He established a new joint Blockade Strategy Board that consisted of representatives from the Navy, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Coast Survey. In July 1861, he began following the recommendations of his new board, which advised capturing ports farther south along the seaboard to extend the range of the blockading squadron.[13] On 9 August, Secretary Welles ordered Stringham to use his squadron to gain control of the Hatteras Inlet, the fortified entrance to a known base of operations for Confederate privateers on the coast of North Carolina.[14]

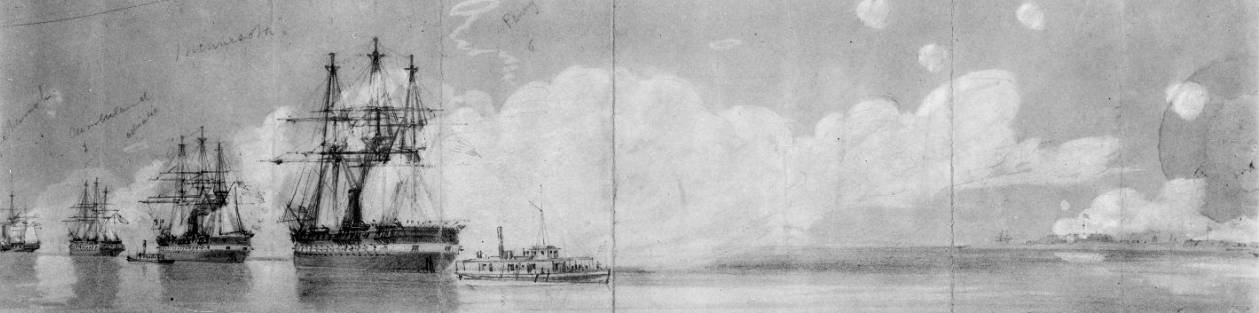

Among the recommendations of the Blockade Strategy Board, the representatives also stressed the importance of amphibious operations. Major General John E. Wool at Fort Monroe received orders to support these actions.[15] Three days before the expected departure of the squadron, Stringham learned that Wool demanded reassurance that he was not responsible to participate further in any operations.[16] Within a day, Wool had orders to send a detachment of 860 men under Major General Benjamin F. Butler on the expedition to Hatteras Inlet.[17] On 26 August, the detachment boarded transport ships to sail with Stringham’s fleet of seven frigates to Hatteras Inlet. Stringham led an expedition from aboard the flagship Minnesota, accompanied by Wabash and three lighter gunboats. Susquehanna and Cumberland followed the next day.[18] All of the ships in this squadron together amassed 143 guns. The Confederate Navy waiting in the coastal waters of North Carolina in August 1861 was hardly a navy compared to their opponent.

At this point in the war, the Confederate Navy still had more officers than fighting ships. Captain Samuel Barron Jr, formerly of the U.S. Navy, was a third-generation naval officer. Ironically, Barron had been accidentally assigned by President Lincoln as Stringham’s replacement as assistant secretary of the Navy in April before Barron resigned his commission. On 20 July 1861, Barron received his first assignment in the new Confederate navy as a flag officer in command of the coastal defenses of Virginia and North Carolina.

BATTLE

All of the ships in Stringham’s expedition except Susquehanna arrived at the Hatteras Inlet on 27 August 1861. The following morning, Minnesota, Wabash, and Cumberland assumed stations to fire upon the forts. Stringham employed a strategy of firing from ships in motion rather than remaining at anchor. Wabash towed Cumberland, the only frigate among them that lacked steam power. The U.S. Army contingent under General Butler prepared to land two miles north of the forts on the following morning.

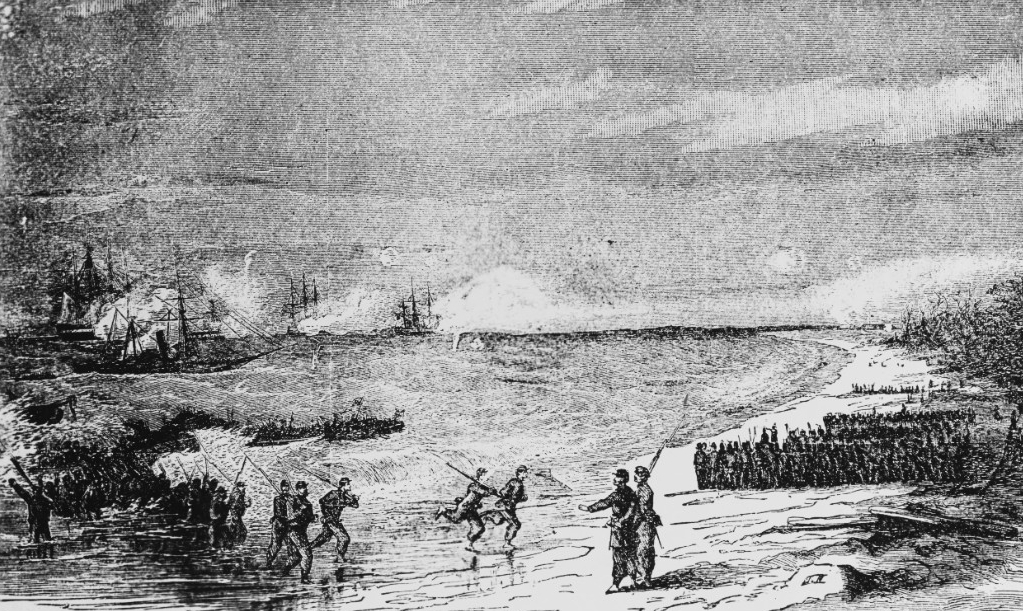

At 0900 on the morning of the 28th, the U.S. Navy squadron reengaged their batteries against Fort Clark as they began making their elliptical passes in front of the inlet. The garrison at Fort Clark attempted to return fire, but their shots continued to fall short of their targets or fly overhead.[19] While the garrison at the forts were distracted by the naval bombardment, Harriet Lane, Monticello, and Pawnee provided protection for the transports, Adelaide and George Peabody, carrying the expeditionary forces toward shore.

Shortly after noon, the garrison at Fort Clark abandoned their post and ran for Fort Hatteras. A few hours later, Captain John P. Gillis, of Monticello, advanced his vessel into the inlet toward Fort Hatteras only to be fired upon by its garrison.[20] From his vulnerable position, Captain Gillis watched as a Confederate steam tug towed a schooner toward Fort Hatteras.[21] The Confederate reinforcements had arrived.

Aboard CSS Winslow, Flag Officer Samuel Barron approached Fort Hatteras on the inland side from the direction of New Bern. His aides, Lieutenants William H. Murdaugh and William Sharp, and Colonel William F. Martin of the 7th North Carolina Volunteer infantry, accompanied him.[22] Commander William T. Muse, of CSS Ellis, landed several companies of North Carolina Volunteers to reinforce the fort. Major Andrews quickly gave command of the remaining fort to Barron. The new commander of Fort Hatteras made plans to retake Fort Clark, but quickly abandoned them during the night.

Caught in the inlet, Monticello returned fire while attempting to back return seaward. Minnesota, Susquehanna and Pawnee arrived to return fire upon Fort Hatteras. At 1800, Stringham pulled back for the night, planning to resume the bombardment in the morning. At 0800 on 29 August, Stringham abandoned the elliptical maneuvers practiced by his ships in the past two days. The ships lined up at anchor to fire upon Fort Hatteras: Susquehanna, Wabash, Minnesota and Cumberland, operating under sail.[23] Later in the morning, Harriet Lane joined in with her rifled guns. [24] The return fire from the Confederate battery continued to fall short of the ships. The superior caliber of the guns used by the U.S. Navy allowed Stringham’s squadron to fire repeatedly upon the forts without any retaliatory rounds reaching their marks. At 1100, the Confederate garrison lowered their flag and raised the white flag in surrender. As the new commander of both forts, Flag Officer Barron negotiated the surrender.[25]

Major General Butler put ashore aboard Fanny to take possession of Fort Hatteras. He returned 615 prisoners to Minnesota. Among those captured were two senior Confederate naval officers: Flag Officer Barron, and Lieutenant Sharp. Colonel Martin of the North Carolina Volunteers, and Major Andrews, formerly in command of Forts Clark and Hatteras, were among the prisoners. [26] Lieutenant Murdaugh, Confederate Navy, escaped being a prisoner as he was put aboard Ellis after he sustained an injury in the fighting on the 28th. The articles of capitulation were signed aboard Minnesota. The U.S. Navy took only minimal damage from the Confederate cannons, and no ships were lost. Monticello and Harriet Lane were in need of repairs although they remained afloat.

AFTERMATH

The battle of Hatteras Inlet marked both the first large-scale naval engagement of the war for the U.S. Navy and its first triumph. With this victory, the Navy gained ownership of the only deep-water access point for the Pamlico Sound, which allowed them utilize the adjacent inland waterways and threaten the Confederate-held territory in North Carolina.

Unable to reinforce the besieged fort, CSS Winslow arrived back at Goldsborough with the news of the loss of Forts Hatteras and Clark. With the loss of Fort Hatteras, Roanoke Island was more important than ever to preserving control of Albemarle Sound. The Confederate high command in North Carolina understood the opportunity that this victory afforded the U.S. forces. Preparations quickly began to protect inland waterways connected to Pamlico Sound and reinforce Roanoke Island.[27] There were plans to recapture their forts, but they never came to fruition, as the Confederate forces in North Carolina prepared to defend against the subsequent attacks that they believed were imminent.

Captain William F. Lynch replaced the imprisoned Samuel Barron as the new commander of the naval defense of North Carolina and Virginia. [28] Lynch quickly reiterated concerns that remained from Barron’s tenure to the Confederate secretary of navy.[29] While the capture of Fort Hatteras was a blow to Confederate morale, Lynch leveraged this loss to request more ships and prepare for an anticipated Federal attack at Roanoke Island.[30]

As the Confederate forces regrouped following their defeat, Flag Officer Stringham personally accompanied the Confederate prisoners on their passage to New York.[31] At the same time, General Butler rushed with the wounded prisoners to Annapolis and directly to Washington.[32] Both Stringham and Butler recognized the strength of this position for potential offensive operations along the coast of North Carolina.[33] Both men wanted the credit for this victory, and both wanted to be the first to suggest occupying the fort rather than blocking the inlet.[34]

Only two days after the surrender on board Minnesota, General Butler gave his report to the President and his cabinet. Butler received the praise that he sought for his participation in the victory, while Stringham was still in New York dealing with the prisoners. Two weeks later, Stringham requested to be relieved of his duty as commander of the Atlantic Blockading Squadron.[35] Welles took this opportunity to divide the squadron. Louis M. Goldsborough took command of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron; Samuel Francis Du Pont took command of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Flag Officer DuPont quickly began planning for an attack farther south. After months of struggling to enforce Lincoln’s blockade, the success of Hatteras Inlet did not save Stringham’s reputation. However, DuPont recognized the success of Stringham’s innovations in ship-to-shore naval bombardment. DuPont used Stringham’s strategy later in his attack at Port Royal, South Carolina.

Despite their success, the Union Navy and its Army counterparts did not follow up on their success at Hatteras Inlet until the following spring. In January 1862, an expedition under command of General Ambrose E. Burnside, U.S. Army, returned with Flag Officer Goldsborough and a plan to capture Roanoke Island.

—Kati Engel, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

***

NHHC RESOURCES

A Brief Naval Chronology of the Civil War (1861-65)

Going South: U.S. Navy Office Resignations & Dismissals On the Eve of the Civil War

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Browning, Robert M. "Defunct Strategy and Divergent Goals: The Role of the United States Navy along the Eastern Seaboard during the Civil War." Prologue, Vol. 33: 169–80.

Moore, R. Scott. The Civil War on the Atlantic Coast, 1861-1865. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2015.

FURTHER READING

Tomblin, Barbara. Life in Jefferson Davis' Navy. United States: Naval Institute Press, 2019.

Torres, Louis. Historic Resource Study of Cape Hatteras National Seashore. Washington: Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984.

***

NOTES

[1] R. Scott Moore, The Civil War on the Atlantic Coast, 1861-1865 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2015), 11.

[2] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (hereafter ORA), 128 vols. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), Series 1, Vol. 1 (1880), 486.

[3] ORA, 1, 1:487.

[4] ORA, 1, 1:487.

[5] ORA ,1,51 (Pt. 2):14.

[6] ORA, 1,51 (Pt. 2):17.

[7] ORA, 1, 1:488.

[8] ORA, 1, 1:488.

[9] Michael E.C. Gery, “The Battle of Hatteras Inlet,” Carolina County, April 2012, accessed April 12, 2021, https://www.carolinacountry.com/carolina-stories/carolina-places/the-battle-of-hatteras-inlet.

[10] Andrews to Clark, 2 August 1861, Governor Henry T. Clark Papers, G.P. 153, Folder 1, North Carolina State Archives, cited in Shane D. Makowicki, “ ‘The Prestige of Success: The North Carolina Campaign of 1862 and the Ascension of Ambrose Burnside,” MA Thesis (Texas A&M University, 2016); ORA, 1, 4: 587.

[11] U.S. Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (hereafter ORN), 30 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922), Series 1, vol. 6, 72.

[12] ORN, 1, 6:5.

[13] ORN, 1, 12:195–200.

[14] ORN, 1, 6:110.

[15] ORA, 1, 4:579.

[16] ORN, 1, 6:109.

[17] ORN, 1, 6:112.

[18] ORN, 1, 6:116–17.

[19] ORN, 1, 6:121.

[20] ORN, 1, 6:121.

[21] ORN, 1, 6:121.

[22] ORN, 1, 6:138.

[23] ORN, 1, 6:122.

[24] ORN, 1, 6:122.

[25] ORN, 1, 6:119.

[26] ORN, 1, 6:119.

[27] ORN, 1, 6:638.

[28] ORN, 1, 6:651.

[29] ORN, 1, 6:726–27.

[30] ORN, 1, 6:729–30

[31] ORN, 1, 6:128.

[32] Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major-General Benj. F. Butler: Butler's Book (United States: A. M. Thayer, 1892), 285.

[33] ORA, 1, 4:585.

[34] ORA, 1, 4:585; ORN, 1, 6:124; Butler, 287–88.

[35] ORN, 1, 6:216.