The Navy Department Library

Chapter IX. Where Sea Meets Land

* * * * *

Tides, current, and surf play a big part in a landing operation. The sea's mood determines not only D-day, but H-hour as well. The invasion of Europe depended on conditions in the English Channel and, like every other water borne assault in World War II, was planned and carried out only after a careful study of sea and coast.

Along the coast of Normandy there is a spring tide of twenty feet. The leaders of the allied forces, aided by Intelligence and weather reports, had to decide whether to set H-hour at high or low tide. At low tide sand bars were likely to hinder landing craft, while at high tide underwater obstacles planted by the Germans were completely covered and likely to cause many casualties and damage to boats. After studying reports, the allied command decided that the attack must be begun when the mines and underwater obstructions were partly exposed. These seemed a greater evil than the sand bars.

Therefore, D-day and H-hour were set on the day and at the hour of the month at which the tide was at its lowest ebb. As is well-remembered, the first assault waves made for the invasion coast on the sixth of June, a few minutes before sunrise. The attack was begun in spite of poor weather and the threat of storms because another equally low tide was not due for weeks. Waiting for clearer weather might have delayed the battle of the Beaches until July.

As a boat crew member, tides, currents, and surf will be closely related to what you do and when you do it. These forces are also bound up with your personal safety and the welfare of your LCM(3) or LCVP. It stands to reason, then, that landing boat crews need to have a clear idea of the nature and effect of surf, tide, and current. First of all, what are they?

Tide

Tide is a change in water level with regard to the bottom of the ocean. When the tide is coming in or flowing, water rises on the beach. While the tide is ebbing or moving out the level of the water goes down. If the beach slopes gently seaward, it makes little difference whether a landing is made at high or low tide. The level of the water becomes important in those areas where there are sand bars and coral reefs. When bars and reefs are to be crossed, landing should be made during high water--unless there are man-made obstacles guarding the coast, as in Normandy.

Along the Pacific coast of the United States, where many men in "amphib" are trained, the tide has a range of about seven feet. There are two high and two low waters every 24 hours. Because of observations ranging back through the years, the height of the water can be predicted within six inches at any time. A strong onshore gale, however, can make the tide vary up to twelve inches from the estimated height.

Deckhands should allow for rise and fall of tide by leaving slack in mooring lines. An LCVP or LCM(3) moored with taut lines at high tide may part them as the tide recedes, lowers the boat, and puts the lines under a strain.

Currents

Currents are horizontal movements of water. Such movements may cover huge areas of sea or they may be limited to smaller coastal stretches or channels. Some currents are created by the wind; others, known as tidal currents, are caused by the tide. The former often affect only the surface of the water, while tidal currents go clear to the bottom of the ocean or channel.

--64--

--65--

--66--

Broad movements of water, such as the Japanese current or the Gulf Stream, are of little importance to landing boat crews. Tidal currents, although often weak near the shore, are likely to influence small boats. This is particularly true in narrow sounds, channels, and openings to lagoons. Sometimes it is difficult for a coxswain to enter a narrow channel against an outgoing or ebbing tide when there are large swells. San Francisco's Golden Gate, where tide and swells meet, is an example. This channel is so frequently choppy that it is called the "Potato Patch."

It is especially important that small boat crews become familiar with the effect of longshore currents inside the breakers. These are likely to be caused by the direction from which swells reach the shallow coastal waters. When swells come in at an angle the longshore current is set in motion. Under such conditions the coxswain must be alert to allow for the action of any such water movement which could swing his boat broadside to the beach.

Breakers and Surf

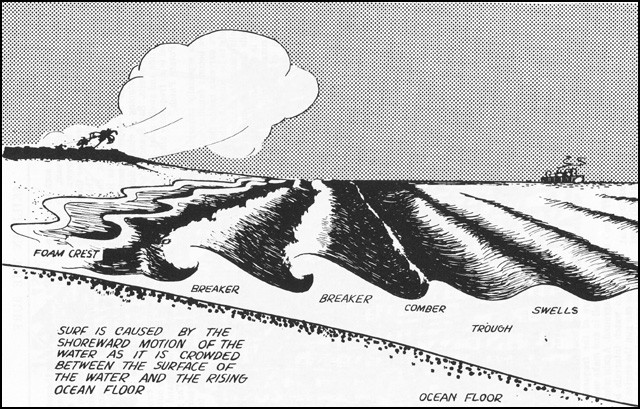

The crews of LCVP's and LCM(3)'s use a number of terms when speaking of the water close in to shore. You can use these words intelligently only if you know their meanings. They should be a part of your vocabulary, so learn them.

Breaker--a single breaking wave.

Breaker line--the outer limit of the surf.

Comber--a wave on the point of breaking. Often a comber has a thin line of white water upon its crest.

Crest--the top of a wave, breaker, or swell.

Foam crest--the top of the foaming water that speeds toward the beach after the wave has broken.

surf--a number of breakers.

Surf Zone--the area between the first break in the swells and the shoreline.

Swell--a broad, rolling movement of the surface of the water.

Trough--the "valley" between waves.

What causes the surf in which landing boat crews receives so many soakings? Actually, surf is created as the swells of the ocean move in toward the beach. As defined above, swells are broad rolling movements of the water surface. (The water particles themselves move very little; only the wave form goes forward.) As this movement approaches the shore it is confined between the rising bottom of the ocean and the surface of the increasingly shallow water as shown in the accompanying diagram. The more confined the motion becomes the more the crests peak up in the form of combers which finally crash upon the beach as surf.

Sometimes there are two belts of surf between the beach and the outer surf line. These are caused by an outer sand bar or reef against which the sea piles up. The movement of water carries over such outer bars, then forms the inner surf belt as it rolls toward the shore.

Experienced small boat handlers know that breakers vary in size and sometimes make the statement that every seventh breaker is higher than the preceding six. It is true that breakers differ in size, but there is no regular pattern or sequence to their height. Sometimes the seventh breaker is higher than the six before it, but the high one can just as easily be the fifth or eighth or eleventh. Also, the order in which the highest breaker comes in varies rapidly. For a short time every sixth breaker may top all others, but two minutes later every ninth one may be highest.

The main thing for the coxswain to remember is that one of the incoming foam crests will lift his boat higher than those immediately before or after. If firmly aground, his best chance to retract comes when the highest crest in a series gives his LCVP or tank lighter the needed floatation.

The space or time interval between breakers varies, but is fairly regular. Breakers may come in every seven or eight seconds, even when the surf is high, or they may crash every 12 or 14 seconds. Whatever the interval, it tends to stay about the same for hours at a time. Along the Pacific coast 12 to 14 second intervals are common in winter and grow shorter during the summer. (Scientists have discovered that the farther a wave travels from its point of origin at sea, the longer the time between breakers striking the shore.)

In landing boat handling the coxswain should be aware of the frequency with which the waves roll in and make use of them to get more firmly aground. Again when retracting, he will need to watch intervals between breakers so that he can gun the engine in reverse each time a foam crest raises the boat.

Local weather conditions have little to do with the condition of the surf. A landing may

--66--

--67--

be dangerous on a mild and pleasant day and easy on a foul and gusty one. This is due to the fact that the swells which cause surf are created by the wind far out to sea. The swells which roll in toward the Pacific coast, for instance, probably began their journey from 1500 to 2000 miles from shore.

In conclusion, there are three main reasons why landing boat crews in general and the coxswain in particular need to have "surf sense." These three points are summarized because they are so vital to safe landings. First, watch the lines of surf and keep the boat at right angles to them. Second, ride in slightly behind the crest of a breaker, and third, gun the engine and retract while a foam crest is under your boat and the keel is free.

A knowledge of surf conditions will aid you to do these three things safely and smartly.

--68--

[End of Chapter 9]