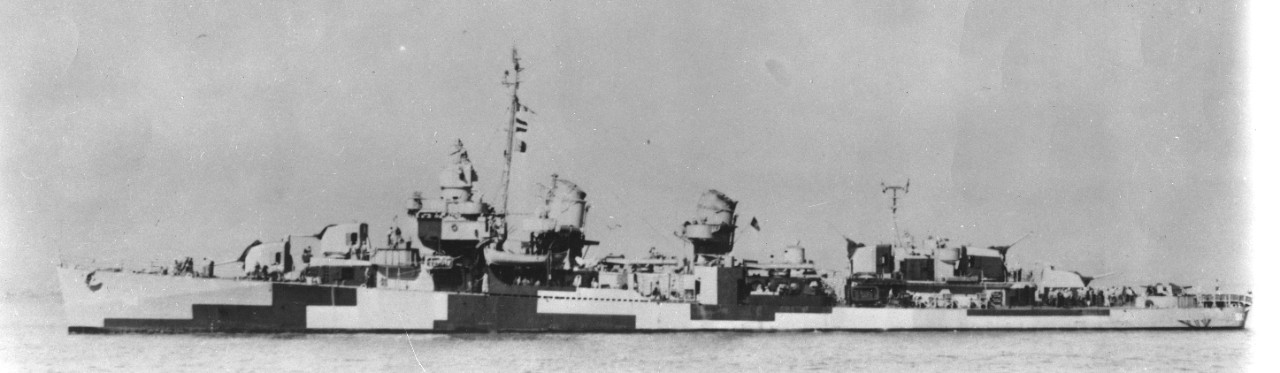

Spence (DD-512)

1943–1944

Robert Traill Spence - born in Portsmouth, N.H. about 1785, to Keith and Mary Whipple Traill Spence – followed his father into naval service. Appointed midshipman on 15 May 1800, Spence reported to the sloop-of-war Warren at Boston, Mass., that October. In July 1801, he received orders to the frigate Boston, but just a month later was assigned to Constitution.

Spence joined Constellation at Philadelphia in December 1801. The frigate sailed for the Mediterranean on 14 March 1802, arriving at Gibraltar on 28 April. By this time, the Barbary State of Tripoli had declared war on the United States after President Thomas Jefferson refused to accede to the Tripolitan demand for a large tribute payment in return for protection of American merchant shipping from pirates. Constellation thus provided an American presence in the region to protect the country’s commercial interests and participated in a blockade of Tripoli. She returned to the United States in March 1803, and Spence then served under the command of Capt. William Bainbridge at Philadelphia with the expectation that he would “employ his leisure moments in nautical studies.”

On 24 May 1803, Spence joined Syren, then nearing completion at Philadelphia. As a member of Como. Edward Preble’s squadron, the brig sailed for the Mediterranean on 27 August 1803. On patrol in the Mediterranean through the summer of 1804, Syren took part in attacks on Tripoli in August and September. On 7 August 1804, Spence was an officer in Gunboat No. 9, a prize taken four days earlier, when a hot shot struck the boat’s magazine. The resulting explosion killed or injured half of the crew of 28 and severely damaged the vessel. With the boat sinking beneath them, Spence and his remaining men loaded and fired the forward gun, giving three cheers as the craft slipped into the sea. Spence was rescued and continued his service in the First Barbary War, returning to the United States in frigate President in September 1805.

After receiving approval in July 1806 to take a furlough for the purpose of sailing to Europe or the East Indies, Spence never actually made such a trip. He was promoted to lieutenant on 8 January 1807. On 26 February, Spence was arrested in New Orleans, La., suspected of involvement in the Burr Conspiracy, an alleged treasonous plot conceived by former Vice President Aaron Burr to foment discord in the American west. Following his arrest, Spence was suspended from the Navy and faced questioning regarding his whereabouts and activities in recent months. After the President determined that Spence’s youth and general good character and especially his gallant conduct in the Navy outweighed his “indiscretions,” he was reinstated to his rank in the Navy on 27 January 1808. Shortly thereafter, he was dispatched to Philadelphia and then Washington, D.C.

In February 1809, Spence went to Boston to serve in Wasp and then returned to Washington in April for duty in John Adams. However, in May he was ordered to New York to join brigantine Argus. In July 1810, he was sent to England with dispatches for the American Minister at London, returning to the United States that autumn. Spence was granted another furlough in May 1811 pending further orders, which arrived in August. He was sent to New York to serve under Como. Stephen Decatur in frigate United States, but in short order he went to Boston to take charge of frigate Chesapeake.

Spence was promoted to master commandant on 24 July 1813. Within a month, he assumed duty as commanding officer of Ontario, supervising the construction and fitting out of the sloop-of-war at Baltimore. By the end of the year, he was also commanding officer of the Baltimore naval station. With the War of 1812 well into its second year and the Chesapeake Bay blockaded by the British, Spence received orders to report for duty on Lake Ontario in April 1814, but he was unable to do so due to his health and remained at Baltimore. In September, Spence earned the praise of Como. John Rogers for his promptness and ingenuity in laying obstructions to impede the British fleet as it approached Baltimore.

The war with Britain officially concluded with the American ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in February 1815. Promoted to post-captain on 28 February, Spence relinquished command of Ontario around this time. He remained in charge of the Baltimore Station until 1 July 1819, and resumed this position on 15 May 1820.

On 20 May 1822, Spence received orders to assume command of the frigate Cyane at New York, with instructions to sail to Puerto Rico and the Spanish Main south of the island to help combat privateering in the West Indies. He later patrolled the African coast to combat piracy and the slave trade there. Returning to the United States in the early summer of 1823, Spence took command of the Baltimore Station once again on 31 July.

In August 1826, Spence learned that he would soon assume command of the West Indian Squadron. However, one month later in mid-September, Spence reported that he was confined to his bed with a bilious inflammatory fever. He passed away at his home near Baltimore on 26 September 1826, leaving behind his wife, Mary Clare Carroll Spence, and seven children.

(DD-512: displacement 2,050; length 376'6"; beam 39'4"; draft 13'5"; speed 35.5 knots; complement 273; armament 5 5-inch, 4 40-millimeter, 5 20-millimeter, 10 torpedo tubes, 6 depth charge projectors, 2 depth charge tracks; class Fletcher)

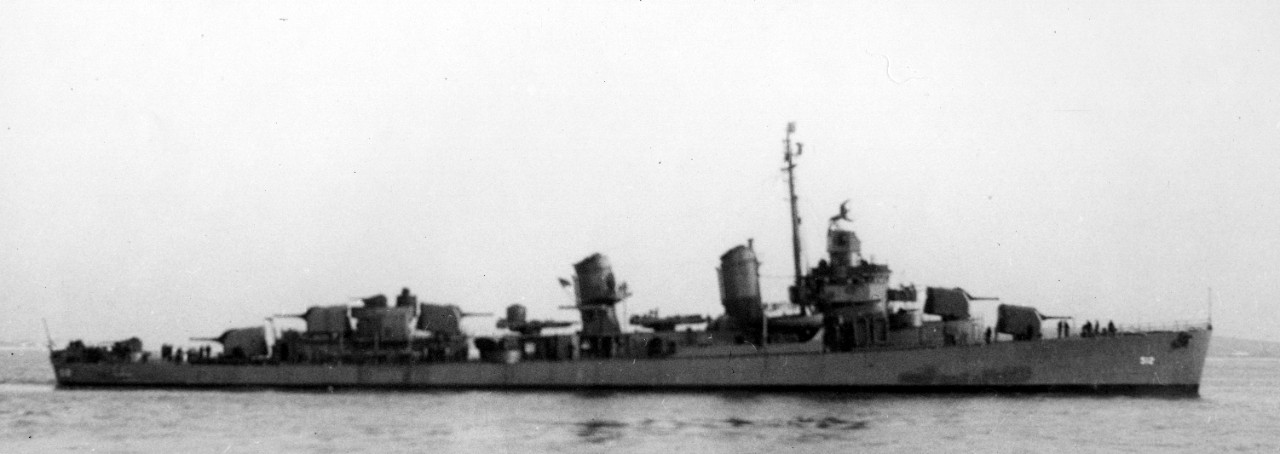

Spence (DD-512) was laid down on 18 May 1942 at Bath, Me., by Bath Iron Works; launched on 27 October 1942; sponsored by Mrs. Eben Learned, great-granddaughter of the ship’s namesake; and commissioned at the Boston Navy Yard, Boston, Mass., on 8 January 1943, Lt. Cmdr. Henry J. Armstrong in command.

After fitting out at the Boston Navy Yard, Spence sailed to Casco Bay, Maine, on 25 January 1943. For the next two weeks, the ship conducted antisubmarine and gunnery exercises. On 8 February, the destroyer stood out in company with Hutchins (DD-476), steaming to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Upon her arrival on 12 February, Spence filled the rest of the month with crew training and shakedown testing of the ship. Once again in company with Hutchins, she set course for Boston on 1 March. Arriving at the Boston Navy Yard on the 5th, the ship spent the next three weeks in maintenance and upkeep, as well as post shakedown alterations.

Spence got underway for New York City on 26 March 1943, arriving at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on the evening of the 27th. On the 31st she moved to anchorage off Sandy Hook Point, N.J., and on 1 April in heavy fog, Spence joined with fellow destroyers Ringgold (DD-500), Foote (DD-511), Stockton (DD-646), Claxton (DD-571), Schroeder (DD-501), Charles Ausburne (DD-570), and flagship Stevenson (DD-645) to form a convoy. Operating as Task Force (TF) 69, the ships escorted merchant vessels across the Atlantic. As the group approached North Africa on the 18th, six British minesweepers, HMS Bude (J.116), HMS Circe (J.214), HMS Derby (J.90), HMS Fantome (J.224), HMS Felixstowe (J.126), and HMS Stella Carina (FY.352), joined the convoy. That same day, Spence detached to search for enemy submarines, rejoining the group early on the 19th. Later that morning, the convoy arrived at Casablanca, French Morocco.

Departing in company with Charles Ausburne, Spence escorted the oiler Enoree (AO-69) to Gibraltar on 21 April 1943, arriving the next morning. Spence and Enoree departed on the 23rd with a group of merchant ships and later that day joined with another convoy escorted by Charles Ausburne. The group rejoined TF 69 on 24 April and proceeded westward in convoy back across the Atlantic. Arriving at New York Harbor on the afternoon of 8 May, TF 69 dissolved and Spence sailed north for Boston in company with Foote and Charles Ausburne. The trio arrived at South Boston Navy Yard on the morning of 9 May. On the 11th, Spence became a member of the newly-established Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 23.

Spence briefly entered floating dry dock Victory on 14–15 May 1943 for inspections and maintenance. After refueling and loading ammunition, the destroyer got underway on the 17th with Foote and Charles Ausburne conducting calibrations and various drills and exercises as they proceeded to Hampton Roads, Va., arriving on the morning of 19 May. On the 20th, Cmdr. Bernard L. Austin, Commander Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 46, hoisted his flag in Spence, and the next day the destroyer departed Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk, escorting the aircraft carrier Yorktown (CV-10) with Schroeder and Foote, which broke down and returned to base later that evening. The warships arrived at NOB Trinidad, British Windward Islands, on the morning of 26 May, and after refueling, Spence got underway again independently en route to New York. She arrived at New York Navy Yard on the 30th, refueled, and departed very early on 31 May to rendezvous with battleship Texas (BB-35), joining Dashiell (DD-659) on escort duty en route to Boston. They arrived at South Boston Navy Yard on the morning of 1 June. The two destroyers stood out again the next day, screening transport Monticello (AP-61) and Army troop transport USAT Edmund B. Alexander to New York. Spence and Dashiell then steamed to Norfolk on 5 June. On the 7th, the two destroyers screened British battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth (00) as she conducted a speed run after completing major repair work. The destroyers were underway again on the 9th, en route to Trinidad with the aircraft carrier Belleau Wood (CV-24).

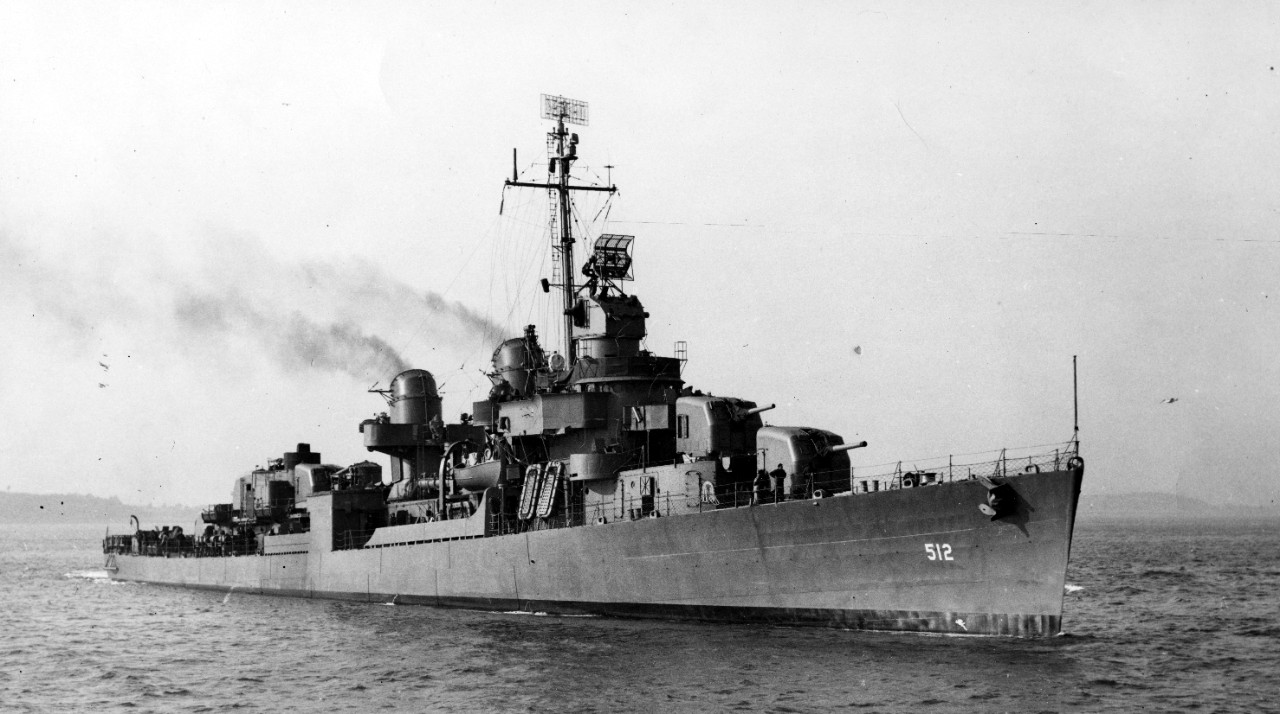

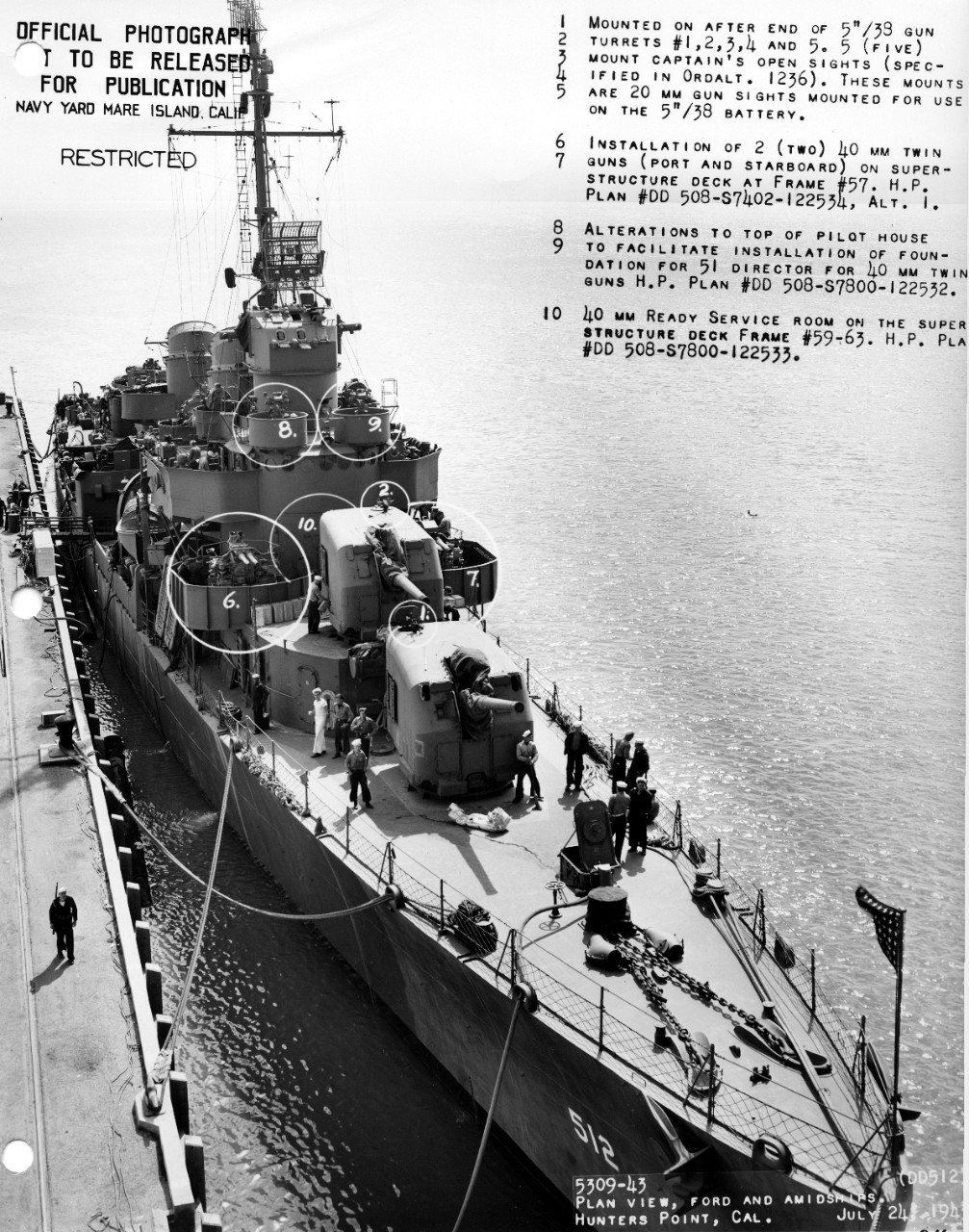

After an overnight at NOB Trinidad, Spence stood out independently on 14 June 1943 and set course for Cristóbal, Panama Canal Zone. She arrived at Naval Station Coco Solo on the 16th and reported for duty with the Pacific Fleet. The following day, the destroyer transited the Panama Canal and moored in Balboa Harbor. In company with her assigned Task Group (TG) 52.1, consisting of Independence (CV-22), light cruiser Mobile (CL-63), and destroyers Schroeder, Brownson (DD-518), Fullam (DD-474), and Thatcher (DD-514), Spence sailed for San Diego, Calif., on 21 June. The task group arrived at Destroyer Base San Diego on the evening of the 28th. On 2 July, Spence, Thatcher, and Independence continued up the West Coast to San Francisco. Spence put in to the Mare Island Navy Yard Annex at Hunters Point on the 3rd for a three-week overhaul period.

On 25 July 1943, Spence shaped a course across the Pacific with Schroeder and Fullam, with Thatcher soon joining the formation. Schroeder detached from the group on the 30th as the destroyers approached Hawaii, and the remaining ships arrived at Pearl Harbor, T.H., on the 31st. Spence was underway on 3 August for torpedo exercises with Thatcher and again the next day screening Mobile and conducting gunnery and radar calibration exercises. She moved to the repair basin at Pearl Harbor on the 5th for maintenance, going into dry dock from 12–17 August. After holding dock trials and refueling, Commander DesDiv 46 broke his flag in Spence, and the destroyer got underway for sea trials on the 21st. However, fifteen minutes into the trial, the No. 1 lube oil service pump failed. The ship continued with her trials and then returned to Pearl Harbor to repair the pump.

Also on 21 August, Spence was assigned to TF 11, which included small aircraft carriers Belleau Wood (CVL-24) and Princeton (CVL-23), USAT President Tyler, dock landing ship Ashland (LSD-1), cargo ship Hercules (AK-41), and destroyers Bradford (DD-545), Boyd (DD-544), and Trathen (DD-530). On 25 August 1943, TF 11 departed Pearl Harbor. Cargo ship Regulus (AK-14) and three auxiliary motor minesweepers joined the formation on the morning of 31 August, and that afternoon, Spence, Boyd, Bradford, and the two carriers detached as TG 11.2 and steamed in the direction of Baker Island to support American troops on the remote outpost 1,900 miles southwest of Honolulu.

At 0905 on 2 September 1943, a Grumman TBF-1 Avenger of Composite Squadron (VC) 24 flying from Belleau Wood splashed off the carrier’s bow. Spence responded and within 15 minutes had rescued Ens. Warren O’Mark, USNR, and AOM3c Max A. Shady of the plane’s crew. The destroyer searched in vain for RM3c F. A. Raitt, the plane’s third crewman, for an additional 20 minutes before resuming her patrol station. Shady suffered multiple severe injuries when the plane’s depth charges exploded as the vehicle sank, and the aviation ordnanceman unfortunately died three hours after the accident. Spence held a burial at sea ceremony for his remains later that evening.

The task group continued onward toward Baker Island. Spence left the formation on 12 September 1943 to screen the oiler Sabine (AO-25). The next morning, the destroyer completed a personnel transfer with Belleau Wood and then stopped briefly at Baker Island to transfer people and equipment. Detaching from TF 11, Spence departed independently en route to Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides [Vanuatu]. The ship received new orders on the 17th, however, and changed course to Efate in the French New Hebrides, arriving at Havannah Harbor the following day.

After exercising south of Efate for the day on 22 September 1943 with the ships of TF 37, led by Washington (BB-56), Spence departed Havannah Harbor independently and joined with Dyson (DD-572) screening the oiler Kankakee (AO-39). On the 24th, the ships rendezvoused with light cruisers Columbia (CL-56) and Cleveland (CL-55) and destroyers Chevalier (DD-451), Charles Ausburne, and Claxton operating south of the Solomon Islands as TG 39.2. Kankakee and Chevalier soon left the formation, and the task group continued on to the Solomons. Operating northwest of Vella Lavella very early on 26 September, Spence fired at two enemy aircraft closing in on the group. Two hours later, Columbia spotted several torpedo wakes close aboard, and Cleveland reported a small submarine on the surface. Spence and Dyson searched for the enemy boat for an hour with no results before returning to the formation. Around midday, the task group arrived at Tulagi Harbor.

In the protracted struggle for control of the Solomon Islands, Japanese and Allied forces had been engaged in battle for Vella Lavella, the most northerly of the New Georgia Islands, since mid-August 1943. As New Zealand troops advanced across the island in late September, the destroyers of DesRon 23 were tasked with destroying any Japanese shipping in the area. From 27 September–1 October, Spence and her squadron-mates conducted several patrols in the vicinity of Vella Lavella and nearby Kolombangara Island, during which Spence engaged enemy planes and fired on a suspected Japanese submarine while other units shelled surface targets believed to be enemy barges.

On 2 October 1943, Spence in company with Charles Ausburne, Claxton, and Dyson escorted Columbia and Cleveland to Espíritu Santo. Upon her arrival the next evening, she tied up next to destroyer tender Whitney (AD-4) for repairs to her boiler drain. Completing her availability on the morning of the 7th, the destroyer headed back to Tulagi accompanied by Stanley and Thatcher and then anchored at nearby Purvis Bay on the 8th awaiting further orders.

In the early hours of 13 October 1943, Spence sailed in company with Nicholas (DD-449), Thatcher, Taylor (DD-468), and Stanly (DD-478) to rendezvous with a convoy of tank landing ships (LSTs) off Cape Esperance, Guadalcanal. The destroyers escorted the convoy to Barakoma Beach, Vella Lavella. The Japanese had evacuated the island during the night of 6–7 October. After completing the convoy escort mission, Spence provided submarine screening services off Guadalcanal for several days. On the afternoon of 20 October, she steamed for Espíritu Santo once again, escorting transport ship Stratford (AP-41), store ship Taurus (AF-25), and fleet tug Pawnee (ATF-74), with the assistance of destroyer escort Osterhaus (DE-164) and minesweeper Token (AM-126).

Spence and her convoy arrived at Espíritu Santo on 23 October 1943. On that day, Capt. Arleigh A. Burke assumed command of DesRon 23. Soon after his arrival, Burke bestowed the nickname “Little Beavers” upon his squadron after observing a torpedoman on board Claxton painting a depiction of the Native American character from a popular comic strip of the day on the side of a torpedo tube. The Little Beaver emblem and moniker quickly became widely-recognized symbols of the squadron’s fighting spirit and a source of pride for her sailors as the ships of DesRon 23 distinguished themselves in battle numerous times over the next several months under Burke’s leadership.

Early on 24 October 1943, Spence stood out with Charles Ausburne, Dyson, Claxton, and Foote to escort cruisers Cleveland and Denver (CL-58) to Purvis Bay. Operating as TG 39.3, the group conducted a simulated shore bombardment, antiaircraft exercises, and a nighttime torpedo attack drill while en route. The ships arrived at Florida Island on the morning of the 25th, with Spence putting in to Purvis Bay to refuel and to make repairs to her starboard engine.

With Vella Lavella now under their control, Allied forces set their sights on the Treasury Islands in the northern Solomons, moving ever closer to the Japanese stronghold at Rabaul on the island of New Britain in New Guinea. On the morning of 26 October 1943, TG 39.3 steamed for the Treasury Islands to provide naval support for amphibious landings on Mono Island. As the group approached the Treasury Islands in the early morning darkness of 27 October, they maneuvered to avoid several enemy planes. At 0359, one Japanese plane dropped two bombs 250 yards off Spence’s port bow, detonating between Spence and Foote but causing no damage. As day broke, TG 39.3 passed the Treasury Islands, where landing operations were already well underway. With Allied fighter planes providing cover for the amphibious landing craft below, the task group was not needed to provide additional support and as such retired to Purvis Bay.

Spence remained at Purvis Bay until the early morning hours of 31 October 1943, when she sortied with the ships of TF 39, steaming toward Buka Island at the northern tip of Bougainville in the northern Solomon Islands. Their objective was to bombard Buka and Bonis, disrupting operations at these Japanese airfields to neutralize a potential source of enemy resistance for the Allied amphibious landings at Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay that would begin at dawn on 1 November. Establishing a base for air operations on Bougainville would bring the Allies within effective striking distance of their ultimate target, the concentration of Japanese forces at Rabaul. Shortly after 1800, the warships formed a column, with Spence in fourth position 3,000 yards ahead of Montpelier (CL-57), and they began to encounter enemy planes within the hour.

At 0020 on 1 November 1943, the task force commenced firing at their targets. “The gun fire from the six-mile column was impressive,” noted Capt. Burke. “The cruisers’ salvos soon had the hills in the foreground silhouetted against the distant fires started in the target area… and the bombardment was a complete success. Apparently it was a complete surprise to the enemy.” The ships ceased fire at 0031 and retired to the south, all the while maneuvering to avoid fire from enemy planes, which Burke described as “a nuisance.” Spence fired on a plane at 0105, another 20 minutes later, and several more over the next half hour. She reported a bomb explosion 2,000 yards astern at 0129 but did not incur any damage.

At 0454, the task force turned east and headed for the Shortland Islands at the southern end of Bougainville. At 0618, shore batteries on Morgusaia [Magusaiai] Island started firing at the column, and the guns of TF 39 returned fire. Spence reported “slow but persistent” gunfire with no shot landing closer than 400 yards from the ship. Her own salvos initially missed their mark, with target spotting made more difficult by haze, smoke, and the sheer number of ships firing, but the destroyer’s gun crews made adjustments, improved their aim, “and definitely silenced one gun on the top ridge.” The engagement continued until 0700, when the task force retired. After the action had subsided, Lt. Cmdr. Henry Armstrong, Spence’s commanding officer, wrote of the experience, “The task served excellently to season this ship in her first of what is hoped may be many more such missions.”

The destroyer had her next chance at battle the following night as the Allied landings at Cape Torokina continued and TF 39 conducted protective screening sweeps off the west coast of Bougainville. Intelligence received from friendly aircraft indicated that a Japanese force consisting of four cruisers and eight destroyers was steaming for Empress Augusta Bay to attack the landing forces. At 0231 on 2 November 1943, TF 39 first made radar contact with the enemy, then 16 miles away. DesDiv 45 fired torpedoes at 0245 and Cruiser Division 12, steaming just ahead of Spence, engaged the oncoming warships with heavy gunfire. Evasive maneuvers put Spence in the line of both enemy and friendly fire splashing about. As the DesDiv 46 flagship made a 90° turn, at 0301 she collided with Thatcher along her port side, fortunately causing only minor damage.

However, less than 20 minutes later, a six-inch shell hit Spence on her starboard side aft. Although the round did not explode, it shattered against the hull, producing a four-foot long diagonal gash extending approximately one foot below the waterline. The opening caused one-two feet of flooding in two crew compartments and fouled two fuel tanks with salt water. The destroyer’s damage control crew temporarily plugged the hole using a collision mat, mattresses, and bags of beans, and while maintaining a watchful eye on the makeshift repair, the destroyer remained in the battle with her task force.

Ten minutes after taking the shell hit, at 0330 Spence fired half a salvo of torpedoes at a Japanese warship 6,000 yards distant, disabling her target. Releasing the remainder of her fish at another enemy ship 3,000 yards away at 0354, Spence observed no visible blast but did note “two very noticeable underwater explosions” great enough to cause the commanding officer to wonder if his own ship had been struck again. A heavy black column of smoke emanated from the second target, however, and Spence opened fire on her prey, striking her mark and setting the enemy destroyer ablaze. Spence’s own battle wounds were beginning to catch up with her though. Low on fuel that had been contaminated with seawater, the destroyer also lost suction which decreased her maximum speed. Spence therefore dropped out of the hunt, leaving Converse and Thatcher to pursue this target.

With the destroyers of DesDiv 46 now scattered, Spence altered course to rendezvous with DesDiv 45, in the process losing her situational awareness of what ships were around her. At 0445, the destroyers of DesDiv 45 mistook Spence for the enemy and opened fire on their sister ship. Fortunately, the error was recognized quickly, the rounds straddled the vessel, and Spence sustained no further damage, although “the ship was the proud possessor of a few pieces of spent shell.” Before she rejoined the squadron, however, Spence detected another potential target group that was believed to be at least three ships strong. The destroyer maneuvered to close position and trained her guns on the enemy. A barrage of direct hits caused several explosions and an intense fire in the targeted ship, rendering her dead in the water. Low on ammunition, Spence requested the assistance of DesDiv 45, which finished off the destroyer Hatsukaze at 0538.

At 0700 on 2 November 1943, Spence and DesDiv 45 reunited with the other ships of TF 39. Spence, Converse, Dyson, and Stanly screened the cruisers while the remaining “Little Beavers” of DesRon 23 trailed behind tending to Foote, which had been disabled by a torpedo several hours earlier. Within the hour, however, a large group of enemy planes closed in on the task force. At 0806, Spence commenced firing at the estimated 60–70 Japanese Aichi D3A1 Type 99 carrier bombers, shooting down several of the Vals, while only the cruiser Montpelier sustained two minor hits during the bombing run. After five minutes of fighting and with friendly planes approaching, the remaining enemy force retired, concluding the day’s action. Although several bombs had splashed near Spence, the destroyer sustained no additional damage.

In company with Converse, Spence detached from the task force that afternoon and proceeded to Port Purvis. Arriving on the morning of 3 November 1943, the ship had a patch welded to her hull to repair the damage from the shell received in action the previous day. After refueling and loading ammunition, she touched briefly at Tulagi on the afternoon of 4 November before reuniting with TF 39 to cover planned amphibious landings at Empress Augusta Bay and Treasury Island. While steaming northwest of Treasury Island on the evening of the 5th, the task force had numerous contacts and encounters with enemy planes. At 2100 with no advance warning from the radar system, a low-flying Japanese aircraft approached Spence from her starboard side, dropped three bombs, and flew directly overhead. With a quick bit of “radical” maneuvering, the destroyer was able to avoid both the bombs, which splashed 75 yards off the starboard side, and the antiaircraft fire directed toward the plane by other ships in the formation. The destroyer suffered no damage, and the next morning she proceeded to Hathorn Sound in Kula Gulf with a task group under the command of Nashville.

The presence of enemy planes overhead brought the ship to general quarters during the mid watch early on 7 November 1943. Spence got underway, but a casualty to her #2 main feed pump soon limited her speed to 25 knots and later 18 knots as the task group steamed to reunite with the rest of TF 39. Toward the end of morning watch, Spence sighted a Japanese soldier in the water attempting to evacuate Treasury Island on a log raft. The man was soon recovered and placed in the ship’s brig. That afternoon, the prisoner was discovered dead in his cell, hanging from the overhead by a belt.

After being relieved on station by Cruiser Division 13, TF 39 returned to Port Purvis, arriving on the morning of 8 November 1943 to refuel and load ammunition. Spence additionally had her feed pump replaced with tender Whitney. The task force departed the next night to return to the operations area, providing cover for amphibious forces en route to Empress Augusta Bay and the Treasury Islands. At 1540 on 10 November, Spence sighted seven Japanese troops, believed to be the crew of a splashed patrol bomber, floating in a life raft. As the destroyer approached the raft to rescue its occupants, one man who appeared to be an officer took out a machine gun. Over the next five minutes, each of the men placed the muzzle of the gun into his own mouth and the officer pulled the trigger. The bodies all fell into the water, to the delight of nearby sharks. The officer then addressed a short tirade to the destroyer’s commander and turned the gun on himself. Spence recovered the raft and returned to the formation.

The task force spent a relatively uneventful night steaming off Bougainville, although Spence did shoot down one Japanese plane in the early hours of 11 November 1943. Later that morning at 1125, two squadrons of Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers flew over the task force, returning to Carney Airfield on Guadalcanal after participating in an airstrike on Rabaul. Shortly thereafter, Spence sighted parachutes in the sky and smoke on the water two miles away and went to investigate. U.S. Army B-24 No. 324 had been badly shot up during the Rabaul engagement with two crewmen injured. Five of the crew bailed in proximity to TF 39, with the remaining aviators attempting to return to base in their damaged plane. Spence rescued the plane’s radio operator, Sgt. William F. Humphrey, who was suffering from a bullet wound to the right shoulder. The other four crewmen who parachuted to the sea were all rescued by other task force vessels.

That evening while steaming west of Treasury Island, enemy planes again harassed the task force. Shortly after the air attacks ended at 2215, Spence received orders to detach from the task force to screen TG 31.7 consisting of Waller (DD-466), Philip (DD-498), Conway (DD-507), Saufley (DD-465), Pringle (DD-477) and eight tank landing ships, LST-390, LST-395, LST-397, LST-398, LST-446, LST-447, LST-449, and LST-472, en route from Empress Augusta Bay to Purvis Bay. The destroyer remained in this role until midday on the 13th, when she continued on to Purvis Bay independently, arriving in the early afternoon.

Spence commenced a week-long tender availability with Whitney to complete essential repairs to her boilers. She got underway again on 20 November 1943 for an engineering test run, but an hour later, a faulty feed pump caused her to return to Point Purvis for additional repairs. After successfully completing her engineering trials on 21 November, Spence stood out from Purvis Bay with DesRon 23 on the 22nd to patrol off Cape Torokina, Bougainville.

Following two days of relatively uneventful patrolling, the squadron engaged with the enemy approximately 50 miles off Cape St. George at the southern tip of New Ireland, New Guinea, on the night of 24–25 November 1943. Searching west of Buka Island for Japanese warships believed to be evacuating aviation personnel from the hard-hit Buka and Bonis airfields to Rabaul, Spence reported two surface contacts on her radar 22,000 yards to the east at 0141. Squadron commander Capt. Burke ordered DesDiv 45 -- Charles Ausburne, Claxton, and Dyson -- to approach the targets and attack. The three ships fired torpedoes at 0155 at a range of 5,500 yards “with devastating results.” Burke reported that one ship, later determined to be the Japanese destroyer Ōnami, “disappeared in a sheet of flame” 300 feet high after a violent explosion and sank immediately. The second ship slowed and started circling.

Meanwhile a second group of targets had been spotted on radar. While DesDiv 45 pursued this new trio of enemy vessels as it sped away to the north, DesDiv 46 -- Converse and Spence --sought to finish off the remaining crippled vessel from the first group. At 0220 Converse fired a half salvo of torpedoes at the hapless victim, the destroyer Makinami. Converse and Spence then maneuvered into position and at 0228 opened fire on the disabled warship, pounding her with numerous direct hits that caused several distinct fires. Numerous explosions rocked the dying vessel, and she finally sank at 0253 following another large blast.

Spence and Converse then moved to rejoin DesDiv 45 in pursuit of the second group of ships, which soon numbered two as punishing gunfire took its toll on the Japanese destroyer Yūgiri and sent her to her watery grave at 0328. The two other Japanese ships had scattered, heading west toward St. George Channel. Unable to locate the remaining ships with daybreak approaching, DesRon 23 set course for Purvis Bay at 0405. The five participating “Little Beavers” dealt a pivotal blow to the Japanese fleet during the Battle of Cape St. George while they themselves emerged from the engagement unharmed. Burke noted that the squadron was “so spontaneously grateful” for its good fortune in the victory that the ships celebrated Thanksgiving services upon their arrival in port late that evening.

Hampered during the week’s operations by a faulty no. 4 boiler limiting her maximum speed to 31 knots, a circumstance that gave rise to the squadron commander’s nickname “Thirty-One Knot Burke,” Spence remained at Purvis Bay for a repair availability until 7 December 1943. Early that morning, the destroyer got underway with TF 39 for another mission to intercept and destroy Japanese ships operating between Buka and Rabaul. However, at 1856 Spence reported that her starboard spring bearing overheated, which limited her speed to only 24 knots. As such, she was ordered to proceed independently to Hathorn Sound to effect emergency repairs if possible and to rejoin the task force when completed or otherwise return to Purvis Bay.

After refueling at Hathorn Sound, Spence proceeded to Port Purvis, mooring next to destroyer tender Whitney early on the morning of 9 December 1943. Work crews then commenced an overhaul of her starboard shaft bearing and engineering plant, which was expected to take one week to complete. On 13 December, Whitney reported to Burke that the destroyer’s starboard shaft might be misaligned and that Spence’s return to action would likely be delayed while workers further examined the shaft and bearings. Two days later, the tender reported that operating the destroyer at high speeds for prolonged periods of time had caused the bearing failure and that the recommended repairs would take nearly two more weeks to complete.

Finally, on 26 December 1943, Spence got underway to conduct engineering trials. Upon returning to Purvis Bay the next morning, Spence required more repairs that would be completed that night. On the morning of the 28th, she once again conducted engineering trials and then reported to Tulagi. The destroyer spent the next two weeks providing escort and screening services for the fleet’s oilers.

Spence rejoined TF 39 on 11 January 1944 at Espíritu Santo and spent most of the rest of the month conducting exercises with the task force in the vicinity of the New Hebrides. On the morning of 27 January, the task force departed Espíritu Santo for combined battle exercises with TF 38, flagship Honolulu (CL-48). At the conclusion of the exercises on the evening of the 28th, TF 39 steamed to Purvis Bay, arriving the next morning.

On 30 January 1944, Spence departed Purvis Bay with DesRon 23 on a mission to patrol for enemy submarines out of sight of land off Buka Island. At 2154 on the 31st, DesDiv 46 --Converse and Spence plus Stanly -- detached from the rest of the group to search north near Green Island [Nissan Island]. After briefly rejoining DesDiv 45 early on 1 February, DesDiv 46 proceeded to Treasury Island while DesDiv 45 continued the search. After refueling, Spence and her division swept the Bougainville Strait before returning to Hathorn Sound on the evening of 2 February.

Departing to patrol the area between Buka Island, Cape St. George, and Green Island again on the morning of 4 February 1944, DesDiv 46 attacked supply and bivouac areas at Hahela Plantation on the southeast coast of Buka Island at dawn on the 5th. That afternoon, the destroyers searched in vain for a reported Japanese gunboat in the vicinity of Green Island, but very early on 6 February, the destroyers sank an enemy barge with two minutes of concentrated gunfire six miles northwest of Green Island. They returned to Hathorn Sound that afternoon. Dispatched once again to search for enemy barges and submarines in the Bougainville Strait on the afternoon of 9 February, DesDiv 46 fired at Japanese targets at Tiaraka and Teopasino, Bougainville, on the morning of the 10th before retiring to Purvis Bay.

Spence put to sea again on 13 February 1944 with TF 39 to conduct operations northeast of Buka Island. After several days with no enemy contacts, at 1300 on 17 February, DesRon 23 split from the force’s cruisers to conduct an anti-shipping sweep north of New Hanover Island, New Guinea. At dawn on 18 February, the squadron began a bombardment of Kavieng at the northern tip of Japanese-occupied New Ireland, with Spence firing first at the town’s airstrip and then at a supply dump. Spence also fired at a Japanese destroyer fleeing from the harbor, but her quarry proved to be just out of range of Spence’s guns. As the squadron retired from the engagement, an enemy plane made two glide bombing runs on the destroyers but the bombs missed their mark and did no harm to the ships. DesRon 23 next went in search of two Japanese destroyers reported in the vicinity of Cape St. George and then shelled a radar station there in the evening.

After refueling at Hathorn Sound, Spence and her squadron conducted an anti-shipping sweep north and west of New Hanover and New Ireland. At 1018 on 22 February 1944, the destroyers finally made contact with what proved to be a 5,000 ton Japanese merchant ship 11 miles distant. Spence and Converse maneuvered to block the target’s escape to the east and the Division 45 destroyers unleashed their guns on the ill-fated vessel, sinking it at 1043 and then plucking 73 survivors from the water while DesDiv 46 screened for enemy submarines.

At 1400, Spence and Converse set off independently to Kavieng, where that evening they fired at the airstrip and the main wharf again for about twenty minutes. They then proceeded to an area 35 miles southeast of Cape St. George to search for a rubber raft with survivors from a Lockheed Ventura bomber crash. The next morning, Spence and Converse rejoined the other division. At 0814, a friendly aircraft spotted the raft and dropped a smoke float nearby. Converse picked up the four survivors while Spence screened the rescue operation. The squadron then retired to Purvis Bay, arriving on the morning of 24 February.

Departing on the evening of 25 February 1944, Spence sailed with DesRon 23 to escort a group of LSTs to Green Island. After completing unloading operations on 1 March, the squadron escorted the LSTs to a position near Lunga Point, Guadalcanal, where they parted company on the 3rd. From 5–11 March, TF 39 took part in a mission to sweep for and destroy any Japanese shipping encountered in the area north of the Bismarck Archipelago of New Guinea on the Truk-Kavieng supply route. The only contact made during the “uneventful” mission, however, was with a Japanese “Betty” that had splashed 30 miles away on the 7th. Spence’s war diary notes “The Task Force had searched to the extreme limits of the area and had operated further North and further West than any U.S. surface Forces had ventured before. But it appeared that the Japanese had given up the area.”

Spence sailed with TF 39 yet again on 17 March 1944, headed this time for an area northeast of New Hanover Island to support landings of amphibious forces on Emirau Island. The landings commenced in the early hours of 20 March and encountered very little resistance. That night, Spence and Converse detached from the task force and spent several hours overnight searching for Japanese barges along the western and southern coasts of New Hanover, operating within 3,000 yards of the shore. The destroyers did not find any targets and returned to the task force, still patrolling south of Emirau, early on 21 March. The task force retired that night, returning to Purvis Bay on the afternoon of the 23rd.

On 24 March 1944, DesRon 23 detached from TF 39 and rendezvoused the next day with TG 36.2, flagship Yorktown, northeast of Bougainville. On the 27th, TG 36.2 joined with four battleships, a carrier, a cruiser division, and a destroyer division. Operating as TG 58.3, the combined forces headed west. On the morning of 30 March, planes from the carriers began air strikes against Palau, which continued through the next day. Japanese planes heckled the task group but did not launch a serious attack against the American warships. After concluding air strikes on Palau on the 31st, the task force steamed toward the Woleai Islands, with airstrikes there commencing at 0645 on 1 April. Retiring to the southeast the next day, TG 58.3 headed for Majuro Atoll, arriving on the 6th. Spence tied up with the repair ship Ajax (AR-6) for emergency repairs to her engineering plant.

Spence returned to action on 13 April 1944, steaming toward the north coast of New Guinea with TF 58. During the evening of 14 April, Spence recovered AOM2c John Ivan Petty, who had slipped off the flight deck of the carrier Enterprise (CV-6). The fortunate aviation ordnanceman improvised a flotation device using his trousers and attracted the destroyer’s attention by whistling and shouting. Spence’s historian noted that Petty was “brought aboard uninjured and only a little tired from his long swim.” Spence then returned to the formation as the task force continued on toward New Guinea. On 21–22 April, the carriers’ planes conducted airstrikes in the Humboldt Bay [Yos Sudarso Bay] area in support of landings by U.S. amphibious forces.

Detaching from the task force on the evening of 23 April 1944, Spence in company with Charles Ausburne and Dyson steamed for Seeadler Harbor at Manus Island in the Admiralty Islands. Upon their arrival on the 25th, the destroyers began overhaul on their boilers and anchors. In the early morning hours of 29 April, the trio got underway to rendezvous with TG 58.3 100 miles north of Manus, rejoining the group the following day. With carrier airstrikes against the once-mighty Japanese base at Truk [Chuuk] already in progress, the three destroyers assumed station as picket ships with the task group. That afternoon, Spence rescued downed aviator Lt. W. B. Redding, USNR, a fighter pilot flying from Monterey (CVL-26). Redding was not injured. After more airstrikes on 30 April, the task force steamed east toward Ponape [Pohnpei] for airstrikes and a battleship bombardment there the next day.

Spence arrived at Majuro Atoll with the task group on the morning of 4 May 1944. From 6–8 May, the destroyer and her sister ships Charles Ausburne, Dyson, and Converse escorted an incoming task group to Majuro. Spence then transferred her fuel to Converse, and on 9 May, she entered the floating dry dock ARD-15, where for the next two days workers repainted the bottom of the ship’s hull and began repairs to her leaking fuel tanks. After undocking, Spence tied up to destroyer tender Markab (AD-21) for the next ten days to complete repairs. The overhaul concluded on the morning of 21 May, and the destroyer was underway briefly to calibrate her magnetic compass.

From 23 May–1 June 1944, Spence operated from Majuro, getting underway several times to complete various training exercises to prepare for upcoming operations with the destroyers of DesRon 23 as well as aircraft carriers Cowpens (CVL-25), Essex (CV-9), and Langley (CVL-27) and cruisers San Diego (CL-53), Reno (CL-96), and Cruiser Division (CruDiv) 13. On the afternoon of 26 May, Spence rescued Ens. Richard Bowers, USNR, whose plane splashed from Cowpens.

Spence sailed from Majuro on 6 June 1944 with TG 58.7, conducting training exercises in fleet tactics and deployment while en route to scheduled operations in the Mariana and Bonin Islands. After completing exercises on the 8th, the task group rejoined TG 58.4. The carriers of the task group began their air assault on Saipan and Tinian on 11 June, with the destroyers watching for submarines and rescuing downed pilots. After two days of airstrikes, the air assault moved to Iwo Jima and Pagan as army and marine troops landed on Saipan on 15 June. As the task group steamed toward a rendezvous with the rest of the task force on the afternoon of the 18th, Spence rescued three crewmen of a plane that splashed during a landing attempt on Cowpens.

On 19 June 1944, TF 58 made contact with several large groups of Japanese planes, which were shot down or dispersed by fighter planes from the carriers or by ships in the task force. The vessels of TG 58.4 remained unmolested by the enemy until early afternoon when one Japanese “Zeke” [Mitsubishi A6M Type 00 carrier fighter] followed a group of American planes back to the carriers undetected. The plane, flying low, dropped a bomb off the starboard bow of Essex, missing the carrier and causing no damage. Spence, on station in the forward screen, fired at the rogue plane but did not hit it. After a refueling rendezvous with TG 50.17 on the 20th, TG 58.4 screened the oilers while the rest of the task force pursued the Japanese fleet and the carrier planes struck first at Rota and Guam and then at Tinian and Saipan over the next several days.

Spence detached from the task group at 0600 on 27 June 1944 with cruisers Miami (CL-89) and Houston (CL-81) and DesRon 23 on a mission to attack enemy shipping and coastal antiaircraft batteries at Rota and in the vicinity of Orote Airfield on Guam. At 0815, Spence fired at a sugar mill at Sosenlagh Bay, Rota. The task unit proceeded to Guam at 0900 and encountered no enemy aircraft or shipping. The warships then began their bombardment of the island, with the destroyers of DesDiv 46 striking barges and fuel tanks in the Apra Harbor area. Spence, Converse, and Thatcher next destroyed a small craft and tank near the shore before conducing an antishipping sweep south and west of Guam. Spence spotted a periscope 2,000 yards from the ship but a sound search yielded no results.

Continuing to patrol the Marianas region with the task group over the next several days, on the morning of 30 June 1944, Spence, Converse, and Thatcher left the formation to conduct heckling operations—slow, deliberate gunfire meant to harass—against Guam and Rota and to search for Japanese shipping southwest of Guam. After rejoining TG 58.4 on 2 July, Spence made her way to Eniwetok over the next several days, arriving on the morning of the 6th. The destroyer refueled and loaded ammunition, and on 8 July she held a change of command ceremony, with Lt. Cmdr. James P. Andrea assuming command from Lt. Cmdr. Armstrong.

Getting underway again with her task group on 14 July 1944, Spence steamed back toward the Marianas to support planned landings on Guam. Arriving south of the island on the night of the 17th, fighters from the carriers began their aerial assault on Guam on 18 July, making multiple airstrikes over the following days. During this time, Spence provided antisubmarine screening for the heavy ships and pursued several sound contacts, dropping depth charges on the 21st. On the evening of 28 July, Spence, Princeton, Langley, Converse, and Thatcher sailed to Saipan, replenished the next morning, and rejoined the task group. The task force reformed on 30 July and proceeded to Eniwetok, arriving on 2 August.

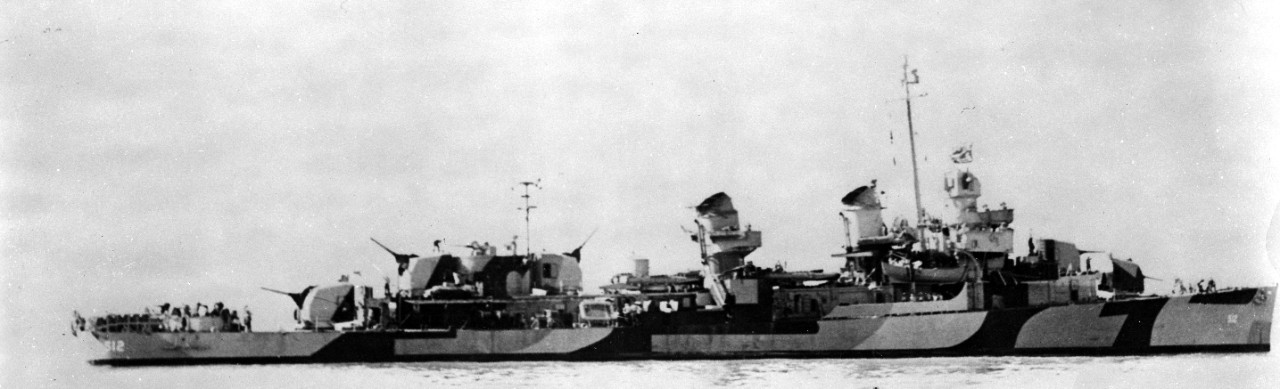

At Eniwetok, Spence received orders to proceed to the continental U.S. for overhaul. Departing on 4 August 1944 in company with Wasp (CV-18), Yorktown, Boston (CA-69), Canberra (CA-70), San Juan (CL-54), Lang (DD-399), Sterett (DD-407), Wilson (DD-408), Charles Ausburne, Dyson, Stanly, Converse, and Thatcher, the destroyer sailed to Pearl Harbor. After arriving on the 10th, Spence refueled and unloaded ammunition, and later that afternoon continued the voyage to California, serving as escort with Converse for attack transports Zeilin (APA-3), President Adams (APA-19), President Jackson (APA-18), and Harry Lee (APA-10). The next afternoon, Spence rescued MM2c Harold M. McCanon who had fallen overboard from Harry Lee. On 17 August, the two destroyers and Zeilin parted company with the rest of the task group which was headed to San Pedro and set course for San Francisco, arriving the next day. Spence sailed to Hunter’s Point Naval Drydocks and began a six-week overhaul, with a dry dock period from 23 August–14 September.

After sea trials and other testing during the first several days of October 1944, Spence completed her overhaul and got underway for Hawaii on the evening of the 5th. Steaming across the Pacific with Charles Ausburne, Dyson, and Converse, Spence reached Pearl Harbor on the afternoon of the 10th. The same group of destroyers conducted a three-day training exercise with destroyer minesweeper Lamberton (DMS-2) from 13–15 October and then over the next several days, Spence exercised with various members of the group refreshing her skills in torpedo tracking, antisubmarine warfare, gunnery, and nighttime maneuvers. Finally on 25 October, the destroyers plus Dewey (DD-349), operating as TG 12.2, departed for Eniwetok, screening the escort aircraft carriers Bismarck Sea (CVE-95), Salamaua (CVE-96), Lunga Point (CVE-94), and Makin Island (CVE-93).

The convoy arrived at Eniwetok on 1 November 1944 and departed again the next morning, continuing on to Ulithi in the Caroline Islands. The group stood into Ulithi on 5 November with a typhoon bearing down on the atoll. Spence, now under the operational control of Third Fleet, rode out the storm at Ulithi, finally taking on ammunition from Rainier (AE-5) at midday on 8 November after storm conditions had subsided. Late on the night of 9 November, Spence received orders to report to TG 38.1, which was then en route to Guam.

On 11 November 1944, Spence stood out from Apra Harbor, Guam, in company with Wasp, Boyd, and Brown (DD-546) to rendezvous at sea with the refueling task group. That afternoon, Spence rescued a pilot flying from Wasp who parachuted from his disabled aircraft after it lost part of its horizontal stabilizer when pulling out of a dive. Less than 24 hours later, Spence again plucked a downed pilot from the sea and returned him safely to Wasp when he was forced to make a water landing after a leak caused his fighter plane to run out of fuel. After fueling at sea on the 13th, Spence rendezvoused with the task force and joined TG 38.1.

During Spence’s absence from the theater of operations while she was conducting refresher training in Hawaii in mid-October, Allied forces had begun to attack and invade the Japanese-controlled Philippine Islands. Amphibious troops landed on Leyte Island and the Third Fleet waged several battles with the Imperial Japanese Navy in Philippine waters. In addition, carrier planes had begun airstrikes in Luzon. Gaining a foothold in the Philippines would help to further isolate Japan's Pacific outposts from each other and would bring the Allies much closer to Japan itself.

On 14 November 1944, Spence screened for submarines as the task group carriers executed airstrikes against targets in the Manila area. The next day as the task group retired to refuel, Spence trailed 25 miles behind the other warships to conduct radar interception exercises. After refueling, the task group returned to the launch area east of Luzon and conducted an additional series of airstrikes against Manila on 19 November. The task group then retired to the east to refuel, detaching from the larger force on 23 November and putting in to Ulithi the following day for a week of repair and upkeep.

Task Group 38.1 got underway from Ulithi on the morning of 1 December 1944 en route to rendezvous with the rest of the task force prior to supporting planned landing operations on the Philippine island of Mindoro. Later that day, however, the ships received word that the action had been postponed ten days to 15 December. As such, the group returned to Ulithi, remaining there through the 9th. On 10 December, Spence was one of several ships reassigned to TG 38.2. The next morning at 0520, Spence sortied from Ulithi assigned temporarily to Task Group 34.5, serving as submarine screen for the battleships and cruisers during gunnery exercises northwest of Ulithi. That evening, TG 34.5 rendezvoused with and joined TG 38.2, which had also departed Ulithi on the 11th. TF 38’s three task groups reunited on 12 December and after refueling at sea with the tanker group on the 13th proceeded at high speed toward Luzon.

At 1742 on 13 December 1944, Spence in company with Hickox (DD-673), Lewis Hancock (DD-675), and Hunt (DD-674) broke away from their task group and began screening Independence, which was serving as TG 38.2’s sole night flight operations carrier. Just before the start of the morning watch, Independence launched the first of three planes that provided combat air patrol to defend against any incoming enemy planes that might ruin the task force’s element of surprise for the mission, which was to target and destroy airfields, planes, and miscellaneous shore facilities on Luzon as well as any enemy warships or commercial shipping in the surrounding waters. The objective was to disable the occupying Japanese forces’ ability to mobilize to defend Mindoro from the American amphibious landing force scheduled to commence an assault on the Philippine island on 15 December. Spence and the ships of her task unit rejoined TG 38.2 at dawn on 14 December, and the fighter planes of TF 38 began their three-day attack on Luzon. Spence once again screened Independence on the night of 15–16 December as the carrier’s planes continued their night heckling runs over Luzon.

After three days of almost continuous airstrikes against the enemy, at 1900 on the evening of 16 December 1944, TF 38 steamed southeast, retiring to refuel with the oilers before returning to the launch area to resume airstrikes on the 19th. The task force reached the tanker group (TG 30.8) the next morning and commenced refueling operations at 1000. “As fueling began,” observed Adm. William F. Halsey Jr., Commander Third Fleet, from his flagship New Jersey (BB-62), “a wind, varying from 20 to 30 knots… and a moderate cross swell made fueling difficult.” Running dangerously low on fuel, Spence came alongside the battleship to replenish at 1107, but only twenty minutes later, both the forward and after fuel lines parted. For two hours, the ships attempted to reconnect, but with the growing swell, the destroyer was unable to maintain her refueling station.

Having received numerous reports from his warships of similar problems with their attempts to replenish, Halsey called off general refueling operations shortly before 1300 and, believing that the storm would curve around to the northeast instead of continuing northwest, ordered the task force and the oilers to proceed westward to a new rendezvous point to resume fueling in the morning. Given her fuel situation, however, Spence was instructed to try to refuel again with the first available oiler. At 1443 she came alongside Cache (AO-67) but once again the weather conditions hindered the operation, so after a half hour, the oiler rigged for the astern fueling method. For two more hours the destroyer attempted to receive fuel from the oiler, but the effort was finally discontinued at sunset. Spence was directed to remain with the tanker group and try to refuel again in the morning.

Early in the morning of 18 December 1944, Adm. Halsey had ordered the task force to change to a southerly course in an effort to avoid the developing storm, but the weather only intensified. “The waves were tremendous, being at least 50 to 60 feet high. The gale was clocked at 115 knots and it was raining, making visibility less than 100 yards.” Spence had only 12–14% fuel remaining, but with the ship being tossed about by the unusually high waves, refueling operations were out of the question. The commander of the tanker task group had earlier advised Spence to take on ballast to help stabilize the ship, and the destroyer began to fill her empty fuel tanks with seawater around 0900. Many TF 38 ships reported dangerous situations as they pitched and rolled dramatically in the violent tempest, including loss of radar and communications due to broken antennae, sailors and aircraft going overboard, power outages caused by water getting into electrical panels, and potentially serious fires that erupted when unsecured aircraft slammed against the sides of the carriers. As experienced by the task force, the typhoon reached its peak intensity early that afternoon, and by evening, the fury of the storm had abated. But none of the task force ships had heard from Spence since that morning.

In several statements made in the months following that tragic day, Lt. (j.g.) Alphonso S. Krauchunas, SC, USNR, Spence’s supply officer, discussed the ill-fated destroyer’s final hours. On the morning of 18 December 1944, as Spence rolled about in the swells, seawater entered the fire room and shorted the electrical system. As a result, at 1100 the ship lost power and was at the mercy of the ferocious winds and angry seas. One huge swell rolled the ship over 75°, practically on her side, but she recovered. The next large wave, however, capsized Spence, trapping most of the ship’s complement of 338 men below. Although 50–60 sailors had been able to escape from the overturning vessel, they now faced a fight for their lives clinging to debris at the height of a raging typhoon, and no one knew they were out there. Many of these men unfortunately did not survive this ordeal.

After the storm subsided that evening, Krauchunas found himself in a group of nine men holding onto a floater net. Their provisions amounted to two kegs of drinking water; other emergency supplies including flares, medicine, and food washed away in the typhoon. With prospects for rescue uncertain, they rationed the water, with each man allowed a swallow every three hours. On the 19th, the sun beat down on them cruelly, but they eventually encountered a can of vegetable shortening bobbing in the ocean that they used to soothe their burnt skin. They saw two search planes fly overhead, but unfortunately the planes did not see them. Three of the nine men on the net died that day.

At 0215 on 20 December 1944, men onboard Rudyerd Bay (CVE-81) heard the shouts of the Spence sailors adrift on the net and dispatched Gatling (DD-671) to investigate. The destroyer dropped a flare in the approximate location of the clamor. Destroyer escort Swearer (DE-186) soon arrived on the scene to assist with the search. The ship circled the flare and reported voices in the water off the starboard bow at 0312. Within ten minutes, Swearer’s searchlight located Krauchunas, Spence’s sole surviving officer, and the other five sailors still on the net, QM2c Edward F. Traceski, USNR; WT3c Charles F. Wohller, USNR; TM3c Albert Roseley, USNR; S1c Maurice D. Sehnert, USNR; and S2c Charles L. Grounds, USNR, and they were brought on board. That afternoon at 1520, search planes from Rudyerd Bay spotted three men in the water tied together with life jackets and a floater ring. Swearer rescued these men as well, also survivors of Spence. Krauchunas reported that two of the men, GM3c Lawrence Callier and S1c Edward A. Miller, USNR, had been unconscious for a while but the third man, St1c David Moore, singlehandedly kept them afloat, saving their lives. Krauchunas and Moore both received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for their lifesaving actions in the aftermath of the sinking.

All told, just 24 men survived the sinking of Spence. TF 38 lost two other ships, destroyers Hull (DD-350) and Monaghan (DD-354), during the typhoon. Several days after the storm as the magnitude of the tragedy began to come into focus, Capt. George C. Dyer, commanding officer of TF 38’s Astoria (CL-90), noted in his ship’s war diary, “The storm has dealt us a blow which the enemy would have liked very much to deliver himself.” Spence was stricken from the Navy Register on 19 January 1945.

Spence was awarded eight battle stars for her World War II service as well as a Presidential Unit Citation as a member of Destroyer Squadron 23 for her role in the Solomon Islands Campaign from 1 November 1943–23 February 1944.

| Commanding Officers | Dates of Command |

| Lt. Cmdr. Henry J. Armstrong | 8 January 1943–8 July 1944 |

| Lt. Cmdr. James P. Andrea | 8 July 1944–18 December 1944 |

Stephanie Harry

18 December 2018