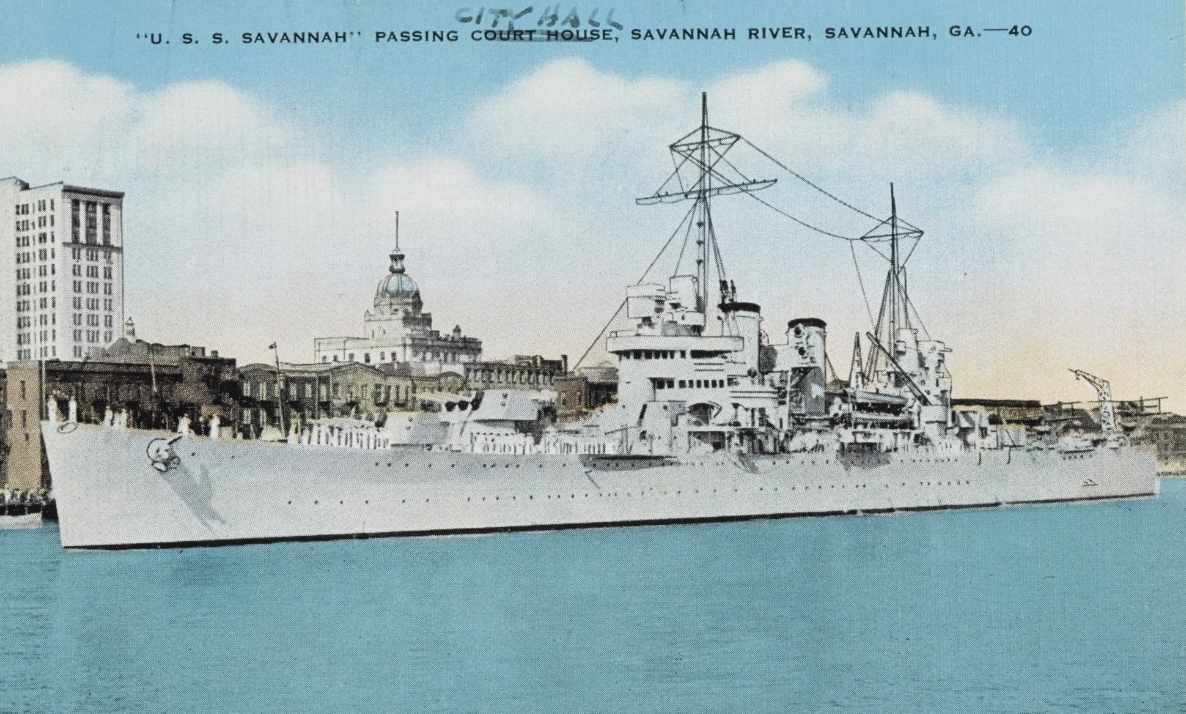

Savannah IV (CL-42)

1938–1959

A large city on the east coast of Georgia.

IV

(CL-42: displacement 9,475; length 608'; beam 69'; draft 19'2"; speed 32 knots; complement 868; armament 15 6-inch, 8 5-inch, 8 .50-caliber machine guns, aircraft 4; class Brooklyn)

The fourth Savannah (CL-42) was laid down on 31 May 1934 at Camden, N.J., by New York Shipbuilding Corp.; launched on 8 May 1937; sponsored by Miss Jayne M. Bowden, niece of Senator Richard B. Russell Jr., of Georgia; and commissioned at the Philadelphia [Pa.] Navy Yard on 10 March 1938, Capt. Robert C. Griffin in command.

A month after commissioning, Savannah sailed on her shakedown cruise, in which she visited Savannah, Ga.; Guantánamo Bay, Cuba; Gonaïves Bay, Haiti; and Annapolis, Md. In the spring on 3 June 1938, Savannah returned to Philadelphia for alterations. The ship began a fruitful association with Cruiser Scouting Squadron (VCS) 8, Lt. Herschel A. Smith in command, when she embarked two of the squadron’s Curtiss SOC-3 Seagulls. Following her yard work, Savannah carried out her final trials off Rockland, Maine, in September. The cruiser, prepared to protect Americans should war break out in Europe, sailed from Philadelphia for England on 26 September, and on 4 October reached Portsmouth. The Munich agreement postponed war, however, so Savannah returned to Norfolk, Va., on 18 October.

The annual fleet problems concentrated the Navy’s power to conduct maneuvers on the largest scale and under the most realistic conditions attainable. Fleet Problem XX ranged across the Caribbean and the northeast coast of South America (20–27 February 1939). President Franklin D. Roosevelt observed the problem initially from on board heavy cruiser Houston (CA-30), transferred to battleship Pennsylvania (BB-38), and then returned to Houston to watch the final exercises, and the chief executive’s presence led to the maneuvers becoming unusually publicized.

Aircraft carriers Enterprise (CV-6) and Yorktown (CV-5) were so new that the referees limited them to operating their air groups during good weather and in daylight. The opponents divided into two fleets, Black and White. Vice Adm. Adolphus Andrews, Commander Scouting Force, U.S. Fleet, led the Black Fleet, which comprised six battleships, Ranger (CV-4), eight heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, 32 destroyers, 15 auxiliaries, and five aircraft tenders. Vice Adm. Edward C. Kalbfus, Commander Battle Force, U.S. Fleet, took the White Fleet to sea, which also counted six battleships, as well as Enterprise, Lexington (CV-2), and Yorktown -- Vice Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander Aircraft, Battle Force, led the carriers -- six heavy cruisers, six light cruisers, 29 destroyers, 12 submarines, and target ship Utah (AG-16) as a surrogate for a trio of large troop ships. The opponents roughly balanced each other in numbers and types of ships, but the White Fleet counted more submarines and the fleets deployed different air strength. The Black Fleet contained only 72 carrier planes but nearly 60 floatplanes embarked on board the battleships and cruisers, 102 patrol planes supported by the tenders in (apparently) safe harbors, and 62 marine planes flying from ashore, and thus deployed stronger reconnaissance and scouting strength. The White Fleet deployed about 220 carrier aircraft and approximately 48 floatplanes on board the battleships and cruisers, and was thus stronger in carrier strength. A “Second Fleet” theoretically supported the White Fleet from an advanced base south of the Azores Islands.

The problem included: employing planes and carriers in connection with escorting a convoy; developing coordinating antisubmarine measures between aircraft and destroyers; and experimenting with various evasive tactics against attacking planes and submarines. Both of the admirals focused on their foe’s air power but in different ways — Andrews attempted to destroy the White Fleet, and Kalbfus used the convoy he was to protect as bait to lure the White Fleet into battle. Rough seas and infrequent rain squalls impeded both sides as they searched for each other on 21 February 1939. Airplanes from Enterprise and Yorktown nonetheless spotted some Black cruisers but they flew under orders to search for Ranger and ignored the enemy ships. A trio of Black heavy cruisers thus slipped past the aircraft and attacked the convoy. Three escorting White heavy cruisers returned the 8-inch salvoes ineffectually, until 72 planes from Yorktown failed to spot Ranger, came about, and pounced on the enemy and sank two of the Black cruisers. The third ship, Salt Lake City (CA-25), attempted to escape only to be sunk by White cruisers. Aircraft from Enterprise and Lexington then discovered and sank two Black light cruisers and damaged another pair.

White destroyers Drayton (DD-366) and Flusser (DD-368) slid past Black’s sentinel Hopkins (DD-249) into supposedly secure Culebra, P.R., during the mid watch on 23 February 1939, sank small seaplane tenders Lapwing (AVP-1) and Sandpiper (AVP-9), shot up some of the patrol planes moored in the harbor, and escaped. The ruse achieved stunning results, but in an effort to economize force, they attempted the same raid at San Juan that morning but the alerted enemy sank both ships. On the morning of 24 February, King directed Enterprise to attack the Black airfields and aircraft tenders and Lexington to find and sink Ranger. The plans including switching the fighters from Enterprise to Lexington and the latter’s scout bombers to the former, a rarely practiced evolution that provided each ship with a specialized air group. Before the carriers could accomplish their novel tactics, however, Black patrol planes flying from Culebra discovered them. Consolidated PBY Catalinas operating out of San Juan and Samana Bay in the Dominican Republic attacked, but the pilots chattered over their radios in the clear and Enterprise and Lexington maneuvered out of harm’s way. Later that day, Capt. Marc A. Mitscher led additional PBYs against the carriers, and although he claimed to knock out Lexington, the umpires ruled that she took only light damage, and that her F3F-1s of VF-3 flying Combat Air Patrol (CAP) and antiaircraft guns exacted a costly toll.

Enterprise reached a position about 120 miles north of San Juan during the morning watch on 25 February 1939, and launched devastating strikes against Black airfields and ships, sinking seaplane tender Langley (AV-3) and an oiler at Samana Bay, and Wright (AV-1) and another oiler at San Juan. The victory raised the total score to four of the Black Fleet’s five aircraft tenders, and the ship achieved another success when Douglas TBD-1 Devastators of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 6 flying from Enterprise discovered the enemy’s main body. The airplanes then began searching for Ranger, which steamed approximately 100 miles from the main body, but Ranger used an experimental high-frequency direction finding system and detected Enterprise, and threw Vought SB2U-1 Vindicators of Bombing Squadron (VB) 3 and Vought SBU-1 Corsairs of Scouting Squadrons (VS) 41 and VS-42 that, in barely two hours smothered the ship’s defenses and sent her to the bottom. The exercises wrapped-up as men of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, made an opposed landing in Puerto Rico to gain an advanced base for the White Fleet.

King criticized Enterprise’s poor performance, which he attributed to her inexperienced air group. Evaluators also noted that the carriers did not embark enough fighters to simultaneously defend the ships and escort strike groups, and recommended raising fighter strength above 18 planes per fighting squadron. The Navy did not adopt the recommendation, however, and rued the cost during the earlier battles of World War II. Controversy also arose over the efficacy of patrol plane attacks on carriers and other ships, and that the principal that patrol aircraft were to operate as scouts required emphasis. In addition, evaluators recommended the necessity of fast battleships to supplement cruisers in carrier task forces. Enterprise and Yorktown afterward visited Fort-de-France, Martinique (6–9 March 1939). Following the maneuvers, Savannah visited her namesake city of Savannah again (12–20 April).

Savannah embarked at times a total of four SOC-3s, and she received one of these Seagulls (BuNo. 1143) (25 May–August 1939) while she was transferred back to the Pacific Fleet. The following day on 26 May, the ship stood out of Norfolk; passed through the Panama Canal on 1 June; anchored at San Diego, Calif., on the 17th; and soon shifted to Long Beach, Calif. The light cruiser continued to train her crew in Californian waters out of Long Beach, nearby San Pedro, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

The warship took part in Fleet Problem XX (1 April–17 May 1940), which consisted of two separate phases around the Hawaiian Islands and eastern Pacific, and involved coordinating commands, protecting a convoy, and seizing advanced bases to bring about a decisive engagement. Savannah set out from Los Angeles for Pearl Harbor, T.H., for the final part of the exercise (15–21 May). The lessons learned during the problem included: the ability of carriers to alter the caliber of their aircraft weapons by changing squadrons; the tendency of commanders to overlook carriers’ limitations and assign them excessive tasks; the necessity for reliefs for flight and carrier crews under actual war conditions; the success of high altitude tracking by patrol aircraft; and the lack of success of low level horizontal bombing attacks.

Savannah conducted battle readiness and training operations with the other ships of Cruiser Division (CruDiv) 8, Philadelphia (CL-41 — the flagship), Brooklyn (CL-40) and Nashville (CL-43), in Hawaiian waters until 8 November 1940. At that time, she embarked four SOC-3s of VCS-8, the squadron led by Lt. Cmdr. Cameron Briggs, which deployed additional Seagulls to the other cruisers. The light cruiser returned to Long Beach on 14 November and soon thereafter completed an overhaul in Mare Island Navy Yard at Vallejo, Calif. She returned to Long Beach, from where she steamed back into Pearl Harbor (20–27 January 1941).

When Japanese aggression had increasingly threatened the Pacific Rim in 1938, a committee under Rear Adm. Arthur J. Hepburn, commandant of the Twelfth Naval District, had investigated possible naval base sites on the coasts of the United States, its territories, and possessions. The Hepburn Board, as it became known, ranked Midway Island as a strategically vital bastion, and recommended expanding the defenses there. Ships deployed the Third Defense Battalion of marines (Lt. Col. Robert H. Pepper, USMC) to the island, and Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Savannah, together with stores issue ship Antares (AKS-3), reached Midway with the balance of the battalion on 13 February 1941.

As war with the Japanese loomed the United States also expanded its naval presence in the Pacific and sought closer ties with prospective allies. Rear Adm. John H. Newton, Commander Cruisers Scouting Force, broke his flag in Chicago (CA-29) in command of a composite squadron that set out from Pearl Harbor with little fanfare or advanced planning on a voyage to the south Pacific on 3 March 1941. “I never could quite figure that [the purpose of the cruise] out,” Capt. Bernhard H. Bieri Jr., her commanding officer, observed, “unless they sort of timed it with the adoption of the signing of the Lend-Lease Act. They wanted to let the Australians know that they weren’t being left out on the limb, I suppose.” On 11 March the U.S. Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act; which, in particular, changed the “cash and carry” provisions of the Neutrality Act of 1939 to permit the transfer of munitions to the Allies.

Chicago sailed in company with Portland (CA-33), Brooklyn and Savannah, and the ships of Destroyer Division (DesRon) 5: Case (DD-370), Cassin (DD-372), Clark (DD-361), Conyngham (DD-371), Cummings (DD-365), Downes (DD-375), Reid (DD-369), Shaw (DD-373), and Tucker (DD-374), and oiler Sangamon (AO-28). Savannah’s crew entered the Ancient Order of the Deep when the ship crossed the equator at 166°17'W, on 7 March 1941. The squadron hove to without warning off Pago Pago, Samoa, and surprised Capt. Laurence Wild, the island’s commandant, when the ships visited that American enclave (9–12 March). Task Group (TG) 9.2, Capt. Ellis S. Stone in command, and consisting of Brooklyn and Savannah, and Case, Cummings, Shaw, and Tucker then (17–20 March) visited Auckland, New Zealand, and from there put in to Tahiti (25–27 March), before returning to Pearl Harbor. Chicago, Portland, Cassin, Clark, Conyngham, Downes, and Reid meanwhile continued separately into the southern latitudes, and returned to Pearl Harbor on 10 April.

Savannah completed voyage repairs and maintenance, and embarked a different set of planes from VCS-8 — three Naval Aircraft Factory SON-1 Seagulls and a single SOC-3. Commander, CruDiv 8, shifted his flag from Philadelphia to Savannah on 16 May 1941. On 19 May, Savannah transferred from the Hawaiian Sea Frontier to the east coast, in order to respond to the growing threat from across the Atlantic as the war in Europe spread. The cruiser set a course for the Panama Canal and passed through the vital waterway on 3 June, almost two years to the day after her first voyage through the canal. The ship crossed the Caribbean via Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, turned up along the east coast, and reached Boston, Mass., on 17 June.

On 4 September 1939, Adm. Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, had directed Rear Adm. Alfred W. Johnson, Commander, Atlantic Squadron, to maintain an offshore patrol to report “in confidential system” the movements of all foreign men-of-war approaching or leaving the east coast of the United States and approaching and entering or leaving the Caribbean. U.S. Navy ships were to avoid making a report of foreign men-of-war or suspicious craft, however, on making contact or when in their vicinity to avoid the performance of unneutral service “or creating the impression that an unneutral service is being performed.” The patrol was to extend about 300 miles off the eastern coastline of the United States and along the eastern boundary of the Caribbean. Furthermore, U.S. naval vessels were to report the presence of foreign warships sighted at sea to the district commandant concerned. President Roosevelt subsequently extended the boundaries of the Neutrality Patrol — on more than one occasion.

As CruDiv 8’s flagship, Savannah carried out Neutrality Patrols in waters ranging south to Cuba and back up the seaboard to the Virginia capes. TG 2.7, comprising Philadelphia, Savannah, Lang (DD-399), and Wilson (DD-408), stood out of Hampton Roads, Va., and accomplished Savannah’s maiden neutrality patrol during a 4,762-mile voyage that concluded at Bermuda (25 June–8 July 1941). Gwin (DD-433) and Meredith (DD-434) faithfully shepherded Philadelphia and Savannah when TG 2.7 carried out a 3,415-mile neutrality patrol from Bermuda and back to that island (16–25 July). Savannah then (3–5 August) trained with TF 17 off New River, N.C.

Rear Adm. H. Kent Hewitt took TG 2.6, built around Wasp (CV-7), and also consisting of Savannah, Gwin, and Meredith, to sea from Hampton Roads on a neutrality patrol as far as Trinidad and the Martin Vaz Islands to Bermuda (25 August–10 September 1941). The task group then swept north from Bermuda to Argentia, Newfoundland, where Savannah arrived on 23 September.

Hewitt’s TG 14.3 comprised Yorktown (CV-5), New Mexico (BB-40), Quincy (CA-39), Savannah, and DesRons 3 and 16, and chartered a course from Argentia for Casco Bay, Maine (10–13 October 1941). Heavy seas battered the ships en route, and Yorktown, New Mexico, Quincy, Savannah, and Anderson (DD-411), Hammann (DD-412), Hughes (DD-410), Mayrant (DD-402), Rhind (DD-404), Rowan (DD-405), Sims (DD-409), and Trippe (DD-403) all suffered damage before they reached safe haven at Casco Bay.

On 25 October 1941, Hewitt’s TF 14, formed around Yorktown, New Mexico, Savannah and Philadelphia, and nine destroyers, set out from Portland, Maine, to escort “Cargo,” the code name for a convoy of British merchantmen. The carrier embarked 18 Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats of Fighting Squadron (VF) 5, 18 Douglas SBD-3 Dauntlesses of VB-5, 19 SBD-3s and a pair of North American SNJ-2 Texans of VS-5, and 18 TBD-1 Devastators of VT-5, along with one F4F-3A, the air group commander’s SBD-3, and the planes of the Utility Unit — a single Curtiss SOC-1, and one Grumman J2F-1 and one J2F-4 Duck. In addition, she carried an SB2U-1 Vindicator in storage. Savannah steamed with TG 14.3 as the Americans screened their charges to within a few hundred miles of the British Isles, before they passed them off to the British on 20 November.

Savannah returned to the United States to complete voyage repairs at New York Navy Yard (24–26 November 1941), and then shifted berths to New York Harbor, where she lay when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. She sailed that momentous day for Casco Bay, and thence made for Bermuda with TG 2.7. Savannah turned her prow to sea in company with Lang and Rhind as the trio screened Ranger while the carrier practiced flight operations on Christmas Eve, and returned to the Allied-held island during heavy rain the following day.

Early in the New Year 1942, the ship joined TG 3.7 and set out on a cruise to assure people of the southern climes of the Western Hemisphere of their continued security that took her to Pernambuco, Brazil (12 January); Montevideo, Uruguay, and Buenos Aires, Argentina (19–24 January); and Santos, Brazil (30 January–2 February). The ship ran low on fuel and the task group staff calculated that she could not return home without dropping to a dangerously low speed while operating in U-boat (German submarine)-infested waters. As a result, Savannah refueled at Port of Spain, Trinidad, on 11 February, before returning to Bermuda on the 14th.

Heavy rain squalls swept through Bermuda a half-hour into the afternoon watch on 22 February 1942, when TG 2.7, comprising Ranger, Augusta (CA-31), Savannah, Lang, Wainwright (DD-419), and Wilson stood out to sea and charted a southerly course to monitor the Vichy French at Martinique in the West Indies.

As the Battle of France had raged (10 May–25 June 1940), a French task group, Rear Adm. Pierre Rouyer in command, loaded $305 million of the Bank of France’s gold reserves and spirited the gold to safety in Canada. Aircraft carrier Béarn brought some of the gold on board at Toulon, France, and the cruisers did so at Brest in that country. The three ships then rendezvoused in the Atlantic and set a course for Canadian waters. On 16 June 1940 the trio set out from Halifax, Nova Scotia, with aerial reinforcements bound for Brest. The ships carried approximately 106 planes: Béarn loaded about 44 Curtiss CW.77 (SBC-4) Helldivers, 17 Curtiss Hawk H-751 (75-A4s), six Brewster B-339B Buffalos -- slated for the Belgians -- and 25 Stinson Model 105 Voyagers. Jeanne d’Arc carried six Hawks and eight Voyagers. The Anglo-French Purchasing Commission bought these aircraft in the United States.

The French and the Germans signed the Armistice, however, as the ships steered an easterly course across the Atlantic. French naval officers considered it imperative that the ships and their valuable cargoes should not fall into German hands, and consequently diverted the convoy to Fort-de-France, Martinique, which the vessels reached on the 27th. Two days later Jeanne d’Arc shifted to Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe. The French initially disembarked the aircraft ashore, some to a warehouse but many to an open field near Pointe des Sables on Martinique, where H. Harward Blocker, the U.S. Vice Consul, recorded that they were exposed to the elements and suffered accordingly with limited maintenance.

The Allies feared that these vessels could potentially fall into enemy hands, and Rear Adm. John W. Greenslade, Commander, Twelfth Naval District and Pacific-Southern Naval Coastal Frontier, negotiated their fate with French Adm. Georges A.M.J. Robert, High Commissioner for the French Territories in the Western Hemisphere and Commander-in-Chief, Western Atlantic Naval Force. The resulting Robert-Greenslade Agreement (5 August–November 1940) guaranteed the non-belligerency of the French ships and the maintenance of the status quo in terms of French sovereignty over their colonial possessions. An American naval observer was to augment Blocker to ensure French compliance, and to monitor the movement of their vessels. The French could purchase food and other supplies from the United States.

Additional vessels including about 20 tankers, transports, merchant cruisers, and torpedo boats joined them at times until by February 1942, an estimated 140,000 tons of Vichy French shipping gathered in the islands. Furthermore, American intelligence analysts feared that the French service de renseignements at Fort-de-France monitored U.S. fleet movements across the Atlantic, and in February the French expanded the detachment for that purpose. The U.S. task group thus steamed off the islands and carefully watched their French counterparts, the ships at one-point closing to within 12 ½ miles as a show of force, steamed off St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, and then came about and returned to Bermuda on the afternoon of 17 March.

Upon Savannah’s return, Greer (DD-145) and Tarbell (DD-142) reported to TF 22 primarily as a screen for the cruiser when required. Savannah lay at Bermuda on 16 April 1942, and during the month also reported her armament as 15 6-inch guns in five triple turrets, eight single 5-inch, two single 3-inch, 12 20 millimeter, and eight .50 caliber machine guns. The ship then (8–21 May) turned her prow southward and operated with Juneau (CL-52) and Lansdale (DD-426) of TG 22.7 off San Juan. Savannah required some work after the nearly constant patrols and thus departed Shelly Bay, Bermuda, on 7 June 1942, and two days later entered Boston Navy Yard for an overhaul. The work included correcting her propeller blades and she completed the overhaul by 15 August. Savannah then sailed for readiness exercises in the Chesapeake Bay to prepare for Operation Torch — the Allied invasion of North Africa. The warship trained with TG 33.1 off Cove Point and Drum Point, and the following month accomplished some additional work while in dry dock at Portsmouth, Va.

The cruiser joined Adm. Hewitt’s Western Naval Task Force, which was to land some 35,000 soldiers and 250 tanks at three different points on the Atlantic coast of French Morocco. As part of the Northern Attack Group, commanded by Rear Adm. Monroe Kelly, Savannah embarked no less than five planes when she hauled on board a trio of SON-1s, an SOC-2, and an SOC-3 of VCS-8. She stood out to sea from Norfolk on 24 October and four days later rendezvoused with the force at a point about 450 miles south southeast of Cape Race. The task force, including the outer screen, covered an area approximately 20 by 30 miles, making it an enormous armada with difficult navigation and security problems. TG 34.2, Rear Adm. Ernest D. McWhorter in command, provided much of the air support and included Ranger (CV-4), Sangamon (AVG-26), and Suwannee (AVG-27) -- commanded by Cherokee Native American Capt. Joseph J. Clark -- and Santee (ACV-29).

Shortly before midnight on 7–8 November 1942, three separate task groups closed on three different points on the Moroccan coast to begin Operation Torch. Savannah's Northern Attack Group was to land the 9,079 men of Sub-TF Goalpost, led by Brig. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott Jr., USA. The assault troops included the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Battalion Landing Teams, 60th Infantry Regimental Combat Team, 9th Infantry Division; 65 M-5 light tanks of the 1st Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, 2nd Armored Division, and the 70th Tank Battalion (Separate); the 1st Battalion, 540th Engineer Shore Regiment; seven coast artillery batteries; and supporting elements.

TG 34.8 comprised cargo ships Algorab (AK-25) and Electra (AK-21), and transports Anne Arundel (AP-76), Florence Nightingale (AP-70), George Clymer (AP-57), Henry T. Allen (AP-30), John Penn (AP-51), and Susan B. Anthony (AP-72). Capt. Augustine H. Gray broke his flag in command of the transports in Henry T. Allen, and was charged with landing the soldiers on multiple beaches (Red, Red 1, Green, Blue, and Yellow) along a nine-mile front on either side of Mehdia — with the first waves scheduled to hit the shore between 0400 and 0500. The soldiers were to seize Port Lyautey and its environs, which included an all-weather airfield. Texas (BB-35), Savannah, and Ericsson (DD-440), Kearney (DD-432), and Roe (DD-418) would provide fire support. Eberle (DD-430), Livermore (DD-429), and Parker (DD-604) were to screen and support the transport area, and maintain antisurface, antisubmarine, and air patrols. A pair of minesweepers, Osprey (AM-56) and Raven (AM-55), also supported the task group.

The Vichy French deployed substantial forces to defend Morocco, including their incomplete battleship Jean Bart, which lay at Casablanca, along with light cruiser Primaguet, two flotilla leaders, and as many as seven destroyers, eight sloops, 11 minesweepers, and 11 submarines. They counted more than 150 army and navy planes in their aerial arsenal, though not all were operational. Four divisions of varying strength, consisting of a mix of European and African troops, garrisoned Morocco.

The French 2ème Escadre Légère (2d Light Squadron), Contre-Amiral Raymond Gervais de Lafonde in command, valiantly attempted to disrupt the landings off Casablanca on 8 November 1942. Naval spotting planes reported the French counterattack and naval gunfire and bombing and strafing attacks including F4F-4 Wildcats from VFs 9 and 41 and SBD-3 Dauntlesses from VS-41 from Rangeroverwhelmed the French. Air attacks sank four submarines, and damaged Primaguet, three destroyers, and a submarine. Wildcats from VF-41 fought French Dewoitine D.520s and Hawk 75As of Groupes de Chasse I/5 and II/5. Planes spotted the fall of shot for ships against coastal emplacements. Massachusetts (BB-59) and bombing and strafing runs by naval aircraft including Wildcats from VF-41 damaged Jean Bart.

Allied planners had developed a bold plan to seize the strategic airfield near Port Lyautey, which lay about nine miles up the shallow Oued Sebou [Sebou River]. Dallas (DD-199), Lt. Cmdr. Robert Brodie Jr., was to carry 75 Army raiders, including a platoon of Company C of the 15th Engineer Battalion, up the narrow and obstructed river to seize the airfield. The channel ran near the south jetty, which compressed the ship into a killing zone. The French also stretched a wire and net boom to block entry into the Sebou, and so George Clymer dispatched her scout boat, led by 1st Lt. Lloyd E. Peddicord, USA, to cut the boom, a half-hour after midnight on the 8th.

The French fortified the Sebou riverbank with two batteries. Batterie Ponsot consisted of two 138.6 millimeter guns and commanded the sea approaches to the river. Défense des Passes, two 75 millimeter pieces on flat cars, covered the ground on the river’s edge below the fortress. In addition, the Kasba, an old masonry fortress that the Portuguese had built centuries before, rose on the edge of a cliff about the river’s mouth, about a mile from the jetties. The fortress blocked the approach to Mehdia and the airfield upriver, and although the French stationed a minimal garrison in the place, they could observe the surrounding area and call down fire on the landing troops — and other troops in the area could reinforce them.

While the drama unfolded off Casablanca that morning of 8 November 1942, the Northern Attack Group approached the northern transport area, about eight miles off the Sebou’s mouth. The ships steamed in two columns, with Savannah leading the left-hand one and Texas the right-hand column. Osprey and Raven (respectively) swept ahead of the columns, and planes flying from Ranger and Sangamonsupported the landings. Chenango (ACV-28) sailed some miles behind the assault forces, and carried 76 USAAF Curtiss P-40F Warhawks of the 33rd Fighter Group, which were to operate from Port Lyautey.

The three U.S. battalions incurred delays but stormed the five assault beaches against mounting resistance on the morning of 8 November 1942. The French opened fire as the Americans worked to cut the boom, delaying their progress, and rushed reinforcements to the fighting, including Foreign Legionnaires and soldiers of the 1er and 7e régiments de tirailleurs marocains [French-led Moroccan soldiers]. The Americans of the 3rd Battalion Landing Team scrambled inland, lugging weapons and equipment five miles to their assigned position. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion Landing Team did not arrive at its intended starting point until about 1000, and, on its way to Port Lyautey, it skirmished with a French battalion. Inter-service coordination broke down several times as different ships insisted on utilizing naval gunfire, while soldiers preferred their own artillery. Inexperienced troops froze under friendly naval gunfire and artillery at several points, holding up infantry attacks.

While the soldiers struggled to establish their beachheads, the French guns near the Kasba opened fire at Eberle, at 0606 on 8 November 1942. At 0630 the enemy increased fire against Roe and straddled her four times. The destroyer rang up 30 knots and beat a hasty retreat to open the range. Savannah supported Roe and fired at the Vichy guns near the Kasba, temporarily teaming with Texas to silence a battery. French planes took off from Rabat-Salé and at 0630 on 8 November 1942, bombed and strafed some of the landing boats. A pair of Dewoitine D.520s considered an American cruiser and her consort to be tempting targets and about 20 minutes later strafed Savannah and Roe, though without inflicting damage.

Savannah’s gunfire against one of the French shore batteries undermined the 2nd Battalion Landing Team’s surprise assault on the river fortress. The French fought defiantly and the cruiser blasted them from their positions and the crew believed that she knocked-out the enemy artillery, only to shift salvoes and learn to their dismay that the French re-manned their guns and continued the battle. Savannahfired 1,196 rounds of 6-inch ammunition and 406 5-inch shells by nightfall. Most of Brig. Gen. Truscott’s troops were ashore, but much of the heavy equipment had not been unloaded, rendering them vulnerable to French counterattacks. The invaders held precarious positions miles from the airfield and without control of the river. Bracing for enemy counterattacks with only seven M-5 light tanks and Savannah’s 6-inch guns, Truscott sent reserves to reinforce the men in the fortress area.

“The combination of inexperienced landing craft crews,” Truscott reported in his Summary of Plans and Operations, “poor navigation, and desperate hurry from lateness of hour, finally turned the debarkation into a hit-or-miss affair that would have spelled disaster against a well-armed enemy intent upon resistance.”

By the next morning, 9 November 1942, Savannah’s 6-inch guns scored a direct hit on one of the two 138.6 millimeter guns in fortress Kasba and silenced the other. Americans who inspected the battery following the French capitulation recorded that Savannah’s direct hit knocked-out that gun, though the other remained salvageable. Nonetheless the fighting continued and 14 French Renault R35 light tanks of the 2c groupe mixtes, 1er régiment des chasseurs d’Afrique, counterattacked along the road to Rabat. Three naval gunfire liaison officers had landed with the first wave of infantry the day before, and they coordinated the cruiser’s shooting as gunfire from Savannah and M-5 tanks, backed-up by aerial runs, defeated the armored thrust, the warship blasting a wood where the French assembled.

Lt. Mark Starkweather, USNR, led a special team to the mouth of the Sebou and cut the net that the French strung across the estuary to block ships from entering the river, during the mid watch on 10 November 1942. At 0400, Dallas turned her prow toward the mouth of the river under the masterful guidance of René Malavergne, a French civilian pilot. Savannah moved clear to enable Dallas to dash up the river, but French guns from the citadel of the Kasba still dominated not only Mehdia but the whole low-lying countryside, and poured a withering fire into Dallas.

Seventy-five millimeter, machine gun, and small arms fire tore into the stripped-down destroyer, but she plowed through mud and shallow water, narrowly missing a pair of river steamers that the defenders sank in order to block the channel, and other obstructions, and sliced through a cable crossing the river and landed the soldiers, who paddled ashore in rubber boats without a casualty. The raiders rendezvoused with men of the 3rd Battalion Landing Team, which advanced overland toward the area, and together they captured the airfield. Savannah supported Dallas while she made her epic thrust into the enemy defenses, and the cruiser stood in and fired 892 6-inch and 236 5-inch rounds at the French batteries for four hours.

During that same day, Savannah’s scout planes set a new style in warfare by successfully bombing tank columns with depth charges, whose fuses had been altered to detonate on impact. The scout planes, maintaining eight hours of flying time daily, struck at other shore targets, and also kept up antisubmarine patrol. One of Savannah’s planes located an enemy 75 millimeter battery which had been firing on Dallas and eliminated it with two well-placed depth charges. The cruiser added to the carnage when one of her 5-inch salvoes touched off a nearby ammunition dump. This action aided Dallas in winning the Presidential Unit Citation.

A provisional assault company of engineers made up of detachments from Company C, 15th Engineer Combat Battalion, the 540th Engineer Shore Regiment, and the 871st Engineer Aviation Battalion participated in an attack on 10 November on the Kasba. Shouting French defenders stood on the walls firing down at the Americans, but U.S. infantry attacks along the ridge and engineer attacks along the river took the Kasba. A small detachment from Company C of the 15th Engineer Battalion rendered the fort’s guns useless. Chenango launched her P-40s and the first Warhawks landed at Port Lyautey at 1030 on 10 November.

The fighting fittingly ended on Armistice Day, when, at 0400 on 11 November 1942, a cease-fire went into effect, the terms of which brought all Goalpost objectives under American control. Through the cease-fire, 172 U.S. carrier aircraft flew 1,078 combat sorties. Forty-four planes were lost but most of their crewmembers survived. These aircraft claimed the destruction of 20 of the estimated 168 French planes deployed to Morocco. That day Barnegat (AVP-10) unloaded more naval aviation supplies for 11 Consolidated PBY-5A Catalinas of Patrol Squadron 73, which flew from Ballykelly, Northern Ireland, to Port Lyautey.

Four days later, Savannah headed home in company with Texas, Sangamon, seven destroyers, Kennebec (AO-36), and four transports, and reached Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk on the last day of November. During the following weeks, the ship reported operating a mix of Naval Aircraft Factory SON-1 and SOC-2 and SOC-3 Seagulls of VCS-8. Savannah trained with Benson (DD-421), Gleaves (DD-423), and Plunkett (DD-431) just before the holidays.

After brief voyage repairs at New York, Savannah sailed in company with Kearney from NOB Norfolk on 25 December to join TF 23 in the South Atlantic Patrol to hunt German blockade runners. The pair rendezvoused with Ericsson (DD-440) and the trio celebrated New Year’s Eve at Trinidad (30 December 1942–2 January 1943), and reached Recife, Brazil, on 7 January.

Teaming with Santee and a destroyer screen -- that included Moffett (DD-362) -- as TU 23.1.6 (12 January–14 February 1943), Savannah returned to sea on an arduous patrol that brought no results. The cruiser put back into Recife, and then steamed out again to search for blockade runners as part of TG 23.1, Rear Adm. Oliver M. Read (21 February–4 March). The group comprised Santee, Savannah, Eberle, and Livermore, and Santee embarked Carrier Air Group (CVG) 29, consisting of 11 F4F-4s of VF-29, and eight SBD-3s and seven Grumman TBF-1 Avengers of Composite Squadron (VC) 29. Savannahfollowed that patrol with a cruise that involved the ship in the pursuit of three blockade runners.

German Hilfskreuzer (auxiliary cruiser) Komet, commanded by Kapitän zur See Robert Eyssen, seized Kota Tjandi, also known at times as Kota Nopan, a 7,322 ton Dutch freighter, and the enemy crew renamed her Karin. The prize ship, Kapitän zur See Klippe in command, set out from Bordeaux in German-occupied France to run the Allied naval blockade in October 1942. On 30 December of that year, Karin reached Singapore, and stood out of that Japanese-occupied port on 4 February 1943, bound again for Bordeaux.

The Germans sailed other blockade runners fully aware of the tight net that the Allies cast about the Third Reich, and directed two other such ships northward through the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland, and on to Stettin in Germany. Enemy submarines including U-191, U-174, U-469, and U-635 were to support the operation. Once the ships passed through the strait, they would rendezvous with the 6th Destroyer Flotilla in Norwegian waters, which would slip the blockade runners and their precious cargoes into enemy-held ports.

Irene, Kapitän zur See Wendt in command, was a prize, ex-4,793 ton Dutch Henry T. Tankreederei’s freighter Silvaplana. German Hilfskreuzer Atlantis, Kapitän zur See Bernhard Rogge, seized her in the South Pacific on 10 September 1941. The ship carried 2,100 tons of valuable rubber for the German war effort, as well as 500 tons of tin, 45 tons of coffee, wax, vanilla, teak — and 50 cases of Balinese souvenir idols.

The third blockade runner, 8,068 ton freighter Regensburg, Kapitän zur See Harder, set out with a cargo of 4,500 tons of rubber and 3,785 tons of whale and coconut oil, as well as 500 tons of tin, 100 of tungsten ore, 100 of tea, and 15 tons of quinine bark from Singapore on 30 January 1943, loaded the quinine bark at Batavia [Jakarta] on Java, and sailed for home in company with Weserland, a 6,528 ton blockade runner, on 6 February. The two parted company at one point because of Weserland’s slower speed, and Regensburg continued homeward.

The Allies searched for these and other blockade runners and on the afternoon of 11 March 1943, TG 23.1 steamed 087° at 15 knots when several of the Wildcats and Avengers sighted a ship about 17 miles from the group, in the South Atlantic about 400 miles west northwest of Ascension Island near 07°21'N, 20°32'W. The vessel steered 320° at 12 knots and showed Dutch colors but the Americans considered her suspicious, primarily because of her specially painted masts. “Never mind Dutch flag, pile in there, this is a runner,” Read directed Savannah and Eberle as they turned and investigated. Both ships manned their battle stations, set a course of 000° and increased to flank speed to intercept the ship, ringing up more turns until they crashed through the swells at 31 knots. Savannah catapulted Plane No. 13 to check out the smuggler, and the two warships fired shots across Karin’s bow.

The Germans stopped Karin’s engines and began to abandon ship. They also set her ablaze in the engineering spaces and some other locations, however, and set four scuttling charges — three of 50 kg and one of 25 kg, with fuse delays of seven to nine seconds. The Seagull swooped down along Karin’s starboard side and fired about 50 machine guns rounds into the water below the boats to prevent the Germans from abandoning ship, but the plane’s gun jammed. Eberle lowered her boarding party in a boat to retrieve intelligence documents at 1647, and as the men approached Karin the flames spread and engulfed the blockade runner amidships. Savannah’s boarding and salvage party left the cruiser at 1654, and she called away the fire and rescue party to battle the blaze.

The boarding party from Eberle arrived alongside, but as they did so three of the powerful time bombs, two planted midships and one aft just before Karin’s four lifeboats got underway, exploded at 1656. The blasts killed 11 boarders and wounded two others. S2c Carl W. Tinsman served in the boarding party and valiantly attempted to save the prize until the explosion ended his life. He received the Silver Star posthumously, and escort ship Tinsman (DE-589) was named in his honor. A Savannah boat rescued an officer and two enlisted men after the explosions blew them into the water. One of the men suffered a badly mangled leg and required medical treatment in the cruiser’s sick bay. Karin sank by the stern in barely a minute and only oil drums, bales of rubber, and other miscellaneous debris floated in the vicinity to mark where the ship took her final plunge. Large numbers of sharks appeared and swam around the area.

The cruiser moved to round up the German lifeboats and capture their occupants, some of whom threw optical gear and weapons overboard as soon as they saw that the Americans intended to pick them up. Savannah took on board the 72 German survivors, 24 naval prisoners and 48 merchant crewmen, and their captors searched and placed the POWs under guard below decks. One of the men had a broken leg in a cast, and another acute arthritis, and both were separated and taken to sick bay under guard. Eberle reported a sound contact at 1800, and Savannah went to 22 knots to escape the apparent U-boat, but 11 minutes later the destroyer’s sonar team evaluated the contact as false echoes. At 1833 Savannah lowered her colors to half-mast in respect to Eberle’s fallen. The cruiser returned to New York on 28 March, where she turned over the prisoners to an intelligence team for interrogation.

The sweep that Savannah and Eberle participated in bore further fruit for the searchers. On 27 March the Germans directed U-174, a Type IXC boat commanded by Oberleutnant Wolfgang Grandefeld, to intercept Karin and Regensburg in a 200 mile wide strip in the North Atlantic. Foul weather delayed the rendezvous between Regensburg and another submarine, most likely U-161, but after they met and while Regensburg steamed toward the Denmark Strait on 30 March 1943, British light cruiser Glasgow (C.21) sighted the blockade runner and the Germans scuttled her near 66°41'N, 25°31'W. Only six of her 118 men survived the heavy seas and bitter northern weather. Irene rendezvoused with U-174and the submarine passed on special orders, charts, instruments, and men on 6 April, but four days later British minelaying cruiser Adventure (M.23) discovered Irene and the enemy scuttled her near 43°18'N, 14°30'W.

Savannah completed an overhaul to ready her for a Mediterranean assignment, and departed Norfolk on 10 May 1943 to protect troop transports en route to Oran, Algeria. She arrived there on 23 May and began preparing for Operation Husky — the Allied invasion of Sicily. The ship joined Boise (CL-47) and Philadelphia in CruDiv 8, and they were to help elements of the 1st Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr., USA, in command, and the 1st and 4th Ranger Battalions, some 19,250 soldiers of the II Corps, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, USA, Seventh Army, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr., USA, land in the sector near Gela. The 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne Division would drop behind the enemy lines near Piano Lupo. Rangers were to assault multiple objectives, including a 900-foot pier at Gela. Additional troops of the Seventh Army landed elsewhere, as did the British Eighth Army, Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery, to the eastward. Savannah was to support TF 81 Gela Attack Force (Dime), Rear Adm. John L. Hall, who broke his flag in attack transport Samuel Chase (APA-56).

The rugged coast precluded large scale landings, however, and enemy coastal defense batteries topped some of the cliffs. The primary beach consisted of a 5,000-yard stretch of shore about a mile east of the mouth of the Gela River. Enemy planes that could counterattack the landings included German Messerschmitt Bf 109G-6s, Focke-Wulf Fw 190F-2s, and Junkers Ju 88As of Luftflotte (Air Fleet) 2, Generalfeldmarschall Wolfram Freiherr von Richtofen, and fighter-bombers and Savoia-Marchetti SM 79s of the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force). Panzer Division Hermann Göring, Generalmajor Paul Conrath in command, a Luftwaffe (German Air Force) division newly reconstituted following its capture in the Tunisian Campaign, stood poised near the area to repel any invaders. Additional German soldiers included elements of the 15th Panzergrenadier Division, and the 2./Schwere Panzer-Abteilung (Heavy Tank Battalion) 504 -- attached to Panzer-Abteilung 215 -- a company of PzKpfw VI Ausf. E Tiger I heavy tanks. The Italian XVIII Coastal Brigade defended the beaches from behind a series of concrete pillboxes and fighting positions, and strung barbed wire entanglements in front of their lines. The Italian 4th Livorno Mountain Infantry Division and the Fiat 3000 tanks of Mobile Group E could reinforce these troops.

Birmingham (CL-62), Boise, Brooklyn, and Savannah joined the invasion formation at 1100 on 9 July 1943. The wind and sea were making up and rose till a fresh breeze drove some tank landing craft behind the formation. Rear Adm. Richard L. Conolly, who led TF 86 Licata Attack Force (Joss), reported that the stragglers experienced great difficulty in keeping up with the formation, and many of the troops struggled with seasickness. Off the Maltese island of Gozo, Rear Adm. Hall divided his ships into three columns, with Savannah to the fore. At 1914 Hall signaled Savannah to take up her approach disposition and to assume tactical command of the Gela Attack Force. Darkness fell and the ships experienced difficulty identifying each other and their assigned positions. Just before midnight, however, Savannahrecognized blue lights that Cole (DD-155) and British submarine Shakespeare (P.221) signaled at a range of about five miles, which aided maneuvering, as did Cole’s utilizing her IFF-3 (identification friend or foe).

Savannah and Shubrick (DD-639) steamed on the left of the invasion area and Boise and Jeffers (DD-621) on the right on the morning of 10 July 1943. Savannah began the battle patrolling her assigned Fire Support Area No. 1 for enemy aircraft, E-boats (motor torpedo boats), and submarines from a distance of 8,000–12,000 yards offshore. Boise and Savannah opened fire on enemy searchlights and shore batteries at 0300. At 0345 the first wave of soldiers hit the beach, and 15 minutes later the pair of cruisers recorded first light and shifted their fire to prearranged targets. “There is continual firing,” Savannah logged at 0400, “all around us at this time.” High winds wreaked havoc with the paratroopers and scattered them over wide drop zones.

A searchlight near Gela suddenly illuminated the boat lanes until Shubrick knocked it out with gunfire. A battery on Long Hill west of Cape Soprano fired several times at the landing craft until Savannah took the guns under fire, at which point the artillery ceased shooting. The ship then shifted to harassing fire on pre-arranged targets until she established communications with a shore fire control party at about daylight.

Axis aircraft dropped flares and attacked Allied ships at 0424. German Bf 109s and Fw 190s flew hit and run raids throughout the landings, strafing the troops on the beaches and the craft offshore, though causing minimal damage. The enemy planes sank Maddox, minesweeper Sentinel (AM-113), and tank landing ship LST-313. Collisions in the crowded waters off the beaches accounted for damage to Roe, Savannah’s companion from Torch, and Swanson (DD-443), and LST-312, LST-345, and submarine chaser PC-621 were among the vessels that sustained damage.

A Ju 88A flew toward Savannah from the west of the cruiser at 0513, and a minute later the ship opened up 20 millimeter and 40 millimeter barrage fire. The Junkers crossed the ship from her starboard bow to port quarter at a height of about 1,000 feet, and some of the ship’s company surmised that the Germans may not have seen the vessel in the dim early morning twilight. Savannah’s gunners and those of nearby ships poured it into the aircraft and dense smoke emerged from the bomber at it crashed toward land. Despite the other ships that shot at the plane, Savannah claimed that she “knocked it down.”

The sun rose at 0530, and at 0606 Savannah launched two of her SOC-3As to spot the fall of shot. Lt. Charles A. Anderson, the pilot of one of the Seagulls (BuNo. 1091), reported no activity on the road or railroad in the ship’s sector at 0628. Savannah and Shubrick meanwhile gamely silenced several shore batteries. At 0641 they were directed to destroy an enemy battery in the Dime landing area that had just begun firing at the invaders.

Out of the blue Bf 109s pounced on both of the Seagulls and shot the first one down, killing Anderson, who received the posthumous award of the Distinguished Flying Cross. Edward J. True, his aviation radioman, landed the perforated plane on the water and escaped before it sank. The Messerschmitts savaged the second Seagull (BuNo. 1097) as well, flown by Lt. (j.g.) John G. Osborn and his radioman, Schradle. The soldiers fighting their way ashore required fire support, so Capt. Robert W. Carey, the ship’s commanding officer and a recipient of both the Medal of Honor and Navy Cross for his WWI service, undauntedly sent the second pair of spotters aloft at 0827. Enemy fighters roamed across the area, and shot down one of those planes and drove the other one off.

Ludlow (DD-439) rescued the crew of one of the Seagulls, Lt. (j.g.) George J. Pinto Jr., USNR, and ARM1c Maples, and pulled True from the water, and returned the three men to the cruiser. Barnett(APA-5) rescued Osborn and Schradle and brought them back to their ship. Savannah afterward observed that the ship could not determine the effectiveness of her fire because she was “unable to keep spotting planes in the air in the face of enemy opposition.” In all, the morning cost Savannah three of her SOC-3A scout planes (BuNos 1091, 1097, and 1146). German planes also shot down of Philadelphia’s spotters, an SOC-3A (BuNo. 1130), killing Lt. Cmdr. Richard D. Stephenson, the pilot, and one of Boise’s, killing ARM2c Douglas W. Pierson.

Another battery laid down accurate barrages on Dime Red 2 Beach, so Boise and Savannah swung their guns around at 0940 and dueled with the enemy artillery. Italian Fiat 3000 tanks spearheaded an enemy counterattack against the beachhead during the forenoon and afternoon watches. Rangers and infantry resisted the onslaught and directed Boise, Savannah, Shubrick, and the 15-inch guns of British monitor Abercrombie (F.109) to fire against the enemy columns during the seesaw battle. The Italians thrust toward the beaches, fell back and regrouped, and determinedly counterattacked again. The Germans then pushed toward the beaches, but the troops ashore and naval gunfire defeated their thrust.

The weather was fair with cloud cover over barely a third of the sky on the morning of 11 July 1943, but at 0635 a flight of 12 SM 79s roared in toward the transports offshore. The planes dropped a bomb that damaged Barnett, killing seven soldiers and wounding 35 more, and fragments from near misses gashed Joseph T. Dickman (APA-13) and Orizaba (AP-24). At 0820 Savannah sadly reported the loss of all of her operational spotting planes.

Heavy surf and the poor beaches impeded the unloading of troops and equipment on the beaches at Gela, and the Italians had damaged the pier the day before. Most of the tanks they managed to land got bogged down in the dunes, and the men ashore thus fought at a tactical disadvantage when the Germans and Italians launched further counterattacks including Tiger tanks. Naval gunfire again supported the soldiers as they repulsed the enemy.

Savannah responded to a call for naval gunfire at two points on a road leading into Gela. She damaged several tanks before shifting her fire to the Butera road to aid advancing American infantry. The heavy salvoes rent the ground around the Italian soldiers, and eyewitnesses described men’s bodies thrown into trees by the detonations. Enemy soldiers desperately sought shelter behind walls and hedges as the steel rained down on them.

The wind veered toward the north during the afternoon watch. At 1355 a flight of an estimated 35 Ju 88As attacked the transports. Savannah steamed at the northwestern corner of the area as the bombers approached from an altitude of 9,000 feet. The Luftwaffe planes flew over the cruiser and as they reached their release point, dropped their bombs and throttled their engines to greater speed to escape the battle. Two of the bombs splashed in the churning waters aft of the ship as she maneuvered and a third ahead but all missed, none of them closely.

Another bomb struck U.S. freighter Robert Rowan at 1545, however, and as the Liberty ship was carrying ammunition she exploded with a devastating blast that shook the anchorage. McLanahan (DD-615) attempted to sink Robert Rowan with gunfire to extinguish the flames from the burning vessel, but shallow water frustrated her efforts and the abandoned merchantman would not sink. Navy landing craft and Orizaba, however, rescued all hands: 41-man merchant complement, 32-man Armed Guard, and 348 troops.

The flames from the stricken vessel nonetheless illuminated the area for some time, and facilitated the next attack by Axis planes when they lunged at the ships offshore. Two of their bombs splashed not far from Savannah as she operated on the outer western edge of the transport area during the raid, which she recorded as the “heaviest bombing attack” of the battle. Allied transport planes carried paratroopers into the fray but they flew through the gathering darkness and the smoke rising from Robert Rowan, which caused confusion among the ships in the roadstead. “As a result,” Savannah sadly noted, “there was much indiscriminate firing. One transport plane was shot down and crashed about two hundred yards from [SAVANNAH], its survivors being rescued by a destroyer.”

The Americans finally landed some M-4 Sherman medium tanks, but soon friend and foe became so enmeshed in the battle that naval gunfire could no longer intervene. Savannah hit more enemy tanks and soldiers but as the battle raged at 1510, Savannah requested that TF 81 notify all ships that U.S. tanks were tangling with the enemy and that vessels should take care to distinguish “friend from enemy.” The cruiser finished out the remaining hours of daylight by helping the Rangers repel an Italian infantry counterattack. Savannah shot more than 500 rounds of 6-inch projectiles by nightfall, gave medical attention to 41 wounded infantrymen, hit enemy troop concentrations inland, and shelled their batteries in the hills.

On 13 July 1943, Savannah had but one call for naval gunfire, and answered by hurling several salvos on the hill town of Butera. Before the 1st Infantry Division pressed on into the interior, it thanked Savannah for “crushing three infantry attacks and silencing four artillery batteries,” as well as for demoralizing the Italian troops by the effect of her fire. The division thanked Savannah in total for “crushing three infantry attacks and silencing four artillery batteries.” Savannah fought at general quarters for nearly 97 hours, and fired 1,890 6-inch rounds before she sailed for Algiers the next day, carrying but a single remaining SON-1 of VCS-8. Conrath later cited naval gunfire as one of the reasons why the Hermann Göring Division failed to drive the invaders into the sea.

While Norwegian cargo ship Bjørkhaug loaded Italian landmines in the harbor of Algiers on 16 July 1943, one of the mines exploded. The blast effectively destroyed the ship, and inflicted hundreds of casualties on people in the area. The flames threatened British cargo ship Fort Confidence, which carried a load of oil, and Dutch tug Hudson bravely took her in tow out to sea, where the crew beached her to prevent further loss. Savannah stood by to render assistance during the fiery ordeal.

Savannah returned to Sicily on 19 July 1943 to support the Seventh Army’s advance along the island’s northwest coast between Santo Stefano di Camastra and Capo d’Orlando (29 July–8 August), and to prevent the enemy from filtering supplies to their troops. The ship carried two SON-1s, an SOC-2, and an SOC-3 of VCS-8. On 30 July, flying the pennant of Rear Adm. Lyal A. Davidson, the fighting ship arrived at Palermo, Sicily, to provide daily fire support. Barrage balloons protected the harbor at an altitude of 2,500 feet, but their defense proved illusory when the Luftwaffe struck.

Her guns helped to repel enemy aircraft raiding the harbor of Palermo on 1 and 4 August 1943. Just before dawn on the 1st, a dark night without moon or clouds, a German Dornier Do 217 bomber flew “high and fast” from an initial detection altitude of 15,000 feet over Palermo. Savannah manned her battle stations and fired 40 5-inch rounds that damaged the plane and killed its rear gunner as the aircraft passed from port to starboard over the ship. The Dornier dropped a bomb that splashed about 500 yards astern of the cruiser, but American-manned Supermarine Spitfires rose to give battle, and the nimble planes intercepted and shot down the bomber. The pilot bailed out and was captured, and upon interrogation described Savannah’s antiaircraft fire as “very accurate.” Nonetheless, the gunners evaluated about 20% of their rounds as “prematures.”

The Dornier may have operated as a pathfinder, however, because a second wave of up to (an estimated) three squadrons of bombers swept in over the harbor just before sunrise that morning. The Germans surprised Savannah and her lookouts suddenly sighted flares at a range of less than five miles and the attackers lumbered in, “low and slow.” The ship shot 300 rounds of 5-inch and 1,200 40 millimeter rounds, but despite the intruders dropping in altitude and speed, her guns fired without scoring a single confirmed hit, as the ship never detected the attackers by radar or visually. Savannah weighed anchor and stood out to sea to escape the risk of further air raids, but returned again and anchored.

Savannah’s SC-2 radar detected German bombers attempting to slip past the Allied defenses and bomb Palermo at an initial detection range of 21 miles on the night of 4 August 1943. The crew manned their battle stations and fired 81 5-inch and 528 40 millimeter shells to port at the bombers, which roared over the harbor. The enemy damaged Mayrant, which had already been hit by Luftwaffe dive bombers while on antiair patrol off Palermo on the 26th. A near miss, only a yard or two off her port bow, during that attack caused extensive damage, rupturing the destroyer’s side and flooding her engineering space, and she was taken in tow into Palermo with five dead and 18 wounded. Mayrant was taken in tow to Malta, where she completed temporary repairs (9 August–14 November).

A 500-pound bomb hit Shubrick amidships, which caused flooding of two main machinery spaces and left the ship without power. She lost nine killed and 20 wounded in the attack. The damaged destroyer was taken in tow into the inner harbor for emergency repairs and then to Malta for drydocking. Using one screw, the ship returned to the United States, arriving in New York on 9 October for permanent repairs. The defenders shot flares to illuminate their fire, but the German planes winged off out of range. The ship also shot at one of the flares in the confusion, her gunners presumably believing it to be dropped by the enemy, and the gunfire “accelerated” its descent. Savannah again weighed anchor after the battle and stood out to sea.

Savannah resumed her duties supporting the Seventh Army’s advance and carried out close and deep supporting fire, interdiction, and harassing fire on call targets in direct support, and interdiction and harassing fire on roadway intersections and strong points well in advance of the soldiers. Army observation planes spotting the ship’s fall of shot during the direct fire support calls, but the ship fired generally without observers when she fired in advance of the troops.

Enemy mobile field artillery fired at the ship during the battles on the 3rd, 4th, and 5th, and her crewmen estimated the guns to range in caliber from 6-inch to 8-inch. The enemy artillerymen knew their job because neither the ship, any of her planes or Army observers, or the troops ashore ever spotted the guns. The best that her men could surmise was that a single gun fired sporadically at the ship on 3 and 5 August, and at least three shot at her on the 4th, apparently from different positions, hurling 27 one to three-gun salvoes at the cruiser. The ship deftly dodged the salvoes without getting hit, though at least one splashed a scant 50 yards away as the enemy gunners found their mark. Savannah nonetheless eluded damage and continued the battle. “The fire of these batteries,” the ship reported to Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, on 24 August, “was annoying but not considered a serious menace.” Having said that, however, Savannah added that the fire from ashore and the location of a minefield “served to keep us at approximately maximum range from our targets for brief periods but not out of range.”

Savannah’s own planes spotting her shooting while flying protected by USAAF fighters on the 2nd and 5th, the only time that she succeeded in arranging fighter escorts with the XXII Air Support Command. During the first few days of the fighting, the ship operated without a means to communicate directly with the fighters. In addition, in accordance with the XXII’s policy, they did not furnish information about when they intended to withdrawal the planes, even after Savannah installed the required radio equipment. Planners did this in order to prevent the enemy from learning by interception whenever the task group steamed unprotected and thus inviting aerial attack. On at least two occasions, however, the policy left the ship’s vulnerable seaplanes in the air for some time over enemy lines without fighter escorts. Heavy and accurate enemy antiaircraft fire compelled the spotting planes to fly a considerable distance to seaward. The aircrewmen thus picked out likely target areas, such as bridges or road intersections, and not specific objectives.

The fighter escorts proved crucial because Savannah’s fire support operating area spread within a range of about 200 miles from 15 German and Italian airfields, four of which lay within 60 miles until Allied troops liberated Catania on the 5th, which cleared two of those four fields from the enemy’s order of battle. “The continuity of air coverage,” the captain succinctly evaluated, “was inadequate to protect the ships proceeding to and from, and while in, support areas…This was apparently due to an inadequate number of fighter planes to meet all air requirements.” In addition, Savannah experienced difficulty identifying friendly planes “due to lack of familiarity with types and inability to identify, and due to action of planes. In one instance, three Allied fighters made a dive toward this ship from a high altitude, and were fired on before they could be identified.”

On 8 August 1943, her task force supported the 30th Regimental Combat Team, including artillery and tanks, when the soldiers landed on a beach nine miles east of Monte Fratello.

“During the day naval guns from the [PHILADELPHIA] and [SAVANNAH][RC1] continued to hit road and railway objectives with marked effect,” is how the Western Naval Task Force summarized the cruiser’s role during the day’s fighting.

The ship came about and, in company with Philadelphia and Abercrombie pounded Agrigento and Porto Espedocle on 16 August 1943 until the enemy garrison surrendered. The Allies captured Messina on 17 August, and that night Savannah and a mixed force of cruisers and destroyers bombarded the Italian mainland near Scilla, near the northern entrance to the Strait of Messina.

“The character of the target was generally unknown at the times of the firing,” Savannah reported to Adm. King, “and the results only occasionally known through information received from the Shore Fire Control Party, or later other Army sources. Such reports indicated the fire was effective and one report from Seventh Army Headquarters credited us with knocking out an eight-inch battery. This was possibly one of the batteries that had been firing at us.”

The crew attempted to overcome difficulties with whatever equipment they could use, at times ingeniously. A transmitter trunk failure caused issues with the ship’s SCR-522A fighter director voice radio, which they had especially installed following the initial landings in Sicily, in order to avoid the communications problems they experienced in that fighting. The men compensated by jury-rigging the broken insulators by tying them up or hanging them with dry clothes line. The crew’s “conduct and discipline” during these actions, Savannah’s commanding officer summarized, “were excellent.”

Savannah returned to Algiers on 10 August 1943 to train with the Army for Operation Avalanche — an assault by the Anglo-American troops of the U.S. Fifth Army on the Gulf of Salerno, Italy. The Italians grew increasingly weary of the war and a coup overthrew Benito Mussolini in July 1943. The Italians negotiated with the Allies to surrender and leave the conflict, and Allied planners thus hoped that by invading the Italian mainland they could induce the Italians to surrender, and trap the German troops deployed to the area. The Allies and the Italians signed an armistice on 3 September 1943, and five days later announced the agreement over the radio. Italian King Victor Emmanuel III, a number of the members of the cabinet, and much of the fleet escaped into Allied hands. They fled without issuing proper instructions to their armed forces to resist, however, and the Germans reacted decisively and launched Fall Achse [Case Axis] — disarming many of the Italian troops and occupying their positions, and in some instances brutally murdering the prisoners after they surrendered. At Salerno Generalmajor Rudolf Sieckenius deployed his 16th Panzer Division in four combined arms battlegroups to counter the landings, and positioned most of his artillery on the high ground, from which the guns dominated the area.

“Effective fire support is almost entirely depending upon the abilities of the Shore Fire Control Parties,” the ship reported to Adm. King on 26 September 1943. “They must be relied upon one hundred per cent to furnish correct information from the beaches, and full faith must be placed in their designation of targets, and spotting. Their responsibilities are so great that it would seem mandatory that prior to any planned operation a thorough understanding exist between them and the ship. With this end in view, SAVANNAH had both the Army Artillery Officers and Naval Liaison Officers on board ship several times prior to sailing. This provided the opportunity for full discussion and permitted the Shore Fire Control Parties to understand the shipboard problems. The Army radio operators were also brought on board, and frequent drills arranged with them. It was unfortunate, that, at the last minute, the task group organization was changed so that SAVANNAH did not work with the party originally scheduled. However, it is believed that such conferences should precede every scheduled operation.”

Leaving Mers-el-Kébir harbor near Oran on 5 September, Savannah operated as part of Task Unit (TU) 81.5.1 in the Southern Attack Force. The ship steamed initially with Fire Support Group 3, however, Boise detached for other duty while en route to the assault area, and Savannah was then directed to relieve her in Fire Support Group 1. The warship received the broadcast of the armistice with the Italians at 1830 on 8 September 1943. Despite the widespread relief that many of the men felt, officers felt it prudent to warn the crew that they still had to fight the Germans.

Savannah went to general quarters at 1905 that evening, and Allied intelligence analysts had identified enemy minefields in the area, so the ship streamed paravanes against the deadly menaces at 2000. At 2117 Luftwaffe planes, some of them carrying torpedoes, attacked vessels and tank landing ships of the Northern Attack Group as they joined up with Savannah and her consorts from the northwest. The ship observed heavy antiaircraft fire and flares during the raid, which lasted for nearly 45 minutes and ended the chances of attaining surprise — if they ever existed. Successful use of smoke disrupted the attackers and the Allies splashed five or six Ju 88s. The light cruiser made good speed and entered Salerno Bay just before midnight at 2315 on the 8th.

Bright moonlight illuminated the night of 9 September 1943, and a calm to moderate breeze varying in direction from south southeast to the southwest touched the air. The sea rolled deceptively calm as the Allied ships approached their designated sectors. Allied planners still hoped to surprise the enemy and decided not to open fire on the defenders unless they lost the element of surprise. Savannah therefore patrolled the outer limits of the fire support area southeast of the transport area, about 20,000 yards off the beaches on the alert for enemy air, surface, or submarine attacks. Cmdr. Alfred H. Richards led TG 81.8 Minesweeper Group, which included 12 auxiliary motor minesweepers and only ten small motor minesweepers, and at 0240 the group reported that the minefields proved more extensive than initially reported — adding that some mines drifted into the boat lanes. Their crewmen set to work but the necessity for sweeping the area clear delayed closing the beaches.

The Luftwaffe persistently returned at 0325 and raided the ships in the Northern Attack Area. The minesweepers continued to sweep but at 0410 reported that they spotted many mines drifting near the assault beaches, and required until daylight to “sweep them up.” The delay proved costly when German planes began dropping flares that burst around and over the assault areas at 0430, and at 0505 the minesweepers signaled that they required even more time to clear the channels, and warned all of the invasion ships to stand clear unless escorted by minesweepers.

The sun rose at 0626 on 9 September 1943, and at 0715 the Luftwaffe returned and Allied fighters intercepted enemy bombers as they approached the invasion armada from the north. A radio message at 0740 warned Savannah that a lone Heinkel He 111 attacked some transports, though the cruiser’s lookouts did not sight the intruder. Enemy planes flew above the clouds at times and four minutes later bombs splashed scarcely 500–1,000 yards from the ship.

The Army dispatched two flights of North American P-51 Mustangs at a time to spot naval gunfire that morning (0800–1000). The planes flew at long range, however, which reduced their loiter time over the beaches to barely 30 minutes. “In thirty minutes,” the ship reported, “the pilot is just becoming oriented and has obtained some conception of the situation on the ground. It is then time for him to be relieved by another pilot who must in turn go through the same process. Thus, there is no continuity of effort, and the pilot never attains a sufficient grasp of the situation to designate targets of opportunity.” Savannah averaged 15–30 minutes to accomplish her fire objectives during each call, which approximated the Mustangs’ time over the battle.

Rear Adm. Lyal A. Davidson, who led TG 81.5 Fire Support Group, disagreed, however, and observed that he was “not fully in accord with the views expressed relative to the use of the P-51s for spotting.” The admiral noted that the Mustangs permitted Abercrombie and Philadelphia to control their shooting when the shore fire control parties “failed to function” because they were “out of communication.” The planes also “furnished valuable reconnaissance data.” He furthermore acknowledged that one of Philadelphia’s Seagulls spotted for her from 1000 to sunset on a following day, and the plane proved of “inestimable value in routing a group of enemy tanks and a field gun in hiding in a brush area north of Fiume Sele between the North and South assault areas and in indicating targets of opportunity.”

Shore Fire Control Party No. 10, consisting of FC10, an Army observer, and NL10, his naval counterpart, spoke to Savannah by radio from separate observation posts. Their dispersal caused confusion on several occasions, and in one such case, one of the observers designated a town as a target just after the other man said that Allied soldiers captured the position. In a further instance, they simultaneously called down fire on two different targets, and every time a salvo landed they both attempted to spot their target. “While it is possible that this was the result of enemy deception,” the ship observed in her report, her radiomen “were positive it was the same persons sending at this time.”

The Germans sent a punishing fire on the Allies and notwithstanding the danger the mines poised, at 0820 on 9 September 1943, Savannah began to stand in 4,000 yards closer to the beaches to aid the hard-pressed soldiers. While the ship did so, however, she recorded “intense aerial activity” as Allied and German planes fought a swirling mêlée about 30 miles to the northward. Savannah nonetheless swung her 6-inch guns around in answer to the shore party’s request and from a range of 22,250 yards fired a three-gun salvo against the three 132 millimeter guns of a railway battery at 0914. The observers called “Cease Firing” after that salvo, most likely to determine the effects of the shooting, and then directed the ship to resume firing on that or another battery (they received Target Nos N 857015 and N 856015, respectively). Savannah laid it on with 19 three-gun salvos from a range of 18,500 yards, and knocked out the enemy rail-mounted artillery (0937-1000).

“Fire support of troops by cruisers,” Rear Adm. Davidson reported to King on 13 October, “primarily a team performance, affords little opportunity for the display of personal prominence by the individual. It is considered, however, that the action of the Commanding Officer, SAVANNAH in closing the range in order to bring fire on an assigned target, despite the several broadcasts of danger from mines and the specific warning from a YMS [auxiliary motor minesweeper], was justified by the situation and showed commendable courage and disregard of personal danger.”

Enemy aircraft attempted to penetrate the Allied CAP and ship screens more than once, yet, the troops needed naval gunfire support, and despite another group of German planes reported inbound from the west at a distance of nine miles at 1050, Savannah moved in toward the beaches an additional 2,000 yards. German PzKpfw IV medium tanks and Sturmgeschütz III assault guns thrust toward the beachhead just before noon, and the shore party anxiously called for naval gunfire. Savannah fired 40 three-gun salvoes and four six-gun salvoes from a range of 17,450 yards that, together with the fire from other ships and the troops ashore, turned back the armored counterattack (1132–1239).

As the fighting continued with unremitting savagery into the afternoon watch, the cruiser unleashed seven three-gun salvoes from 17,050 yards against enemy troops (1321–1339), and then (1419–1437) 18 three-gun salvoes against an observation post. Savannah again answered frantic pleas for help from the men struggling on the beaches. The ship closed in to 12,000 yards at 1355, passing minesweepers that worked to either side of her to clear channels. Savannah launched a pair of Seagulls for a single flight to spot for Philadelphia, Rear Adm. Davidson’s flagship, and the planes searched the area for mines, and reconnoitered over the beaches. Although the Luftwaffe did not attack them, the ship’s company bitterly recalled the debacle in Sicilian waters. “The fact still remains,” Savannah reported to King, “that they are entirely unsuitable for this type of task because of their vulnerability.”

Undaunted, the 16th Panzer Division again attempted to oust the invaders, and Savannah closed to 13,200 yards and shot a trio of three-gun salvoes (1449–1508), until the shore party informed the ship to “cease firing, target has disappeared.” Next (1535–1603)), an artillery battery felt the weight of Savannah’s ire as the ship fired 13 three-gun salvoes from 16,400 yards. The ship maneuvered at a range of 19,900 yards from the little town of Capaccio, from which the routes to the east could be controlled, as the 36th Infantry Division’s 143rd Regimental Combat Team advanced on the settlement. She fired three two-gun salvoes (1654–1708) at enemy troops near the town, and the Germans pulled out and the soldiers captured it without further opposition.

German artillery bracketed the beachhead and Savannah blasted one such position from a range of 11,250 yards with 30 three-gun salvoes (1716–1757), until the shore party understatedly reported “area covered.” Allied ships answered calls for fire support while maneuvering through the treacherous minefields, but at 1723 Abercrombie struck a mine that caused such serious damage to the monitor that she required repairs into December. Savannah recovered her two Seagulls a couple of minutes later, but the ships endured unrelenting German aerial attacks as planes dive bombed tank landing ships and struck transports.

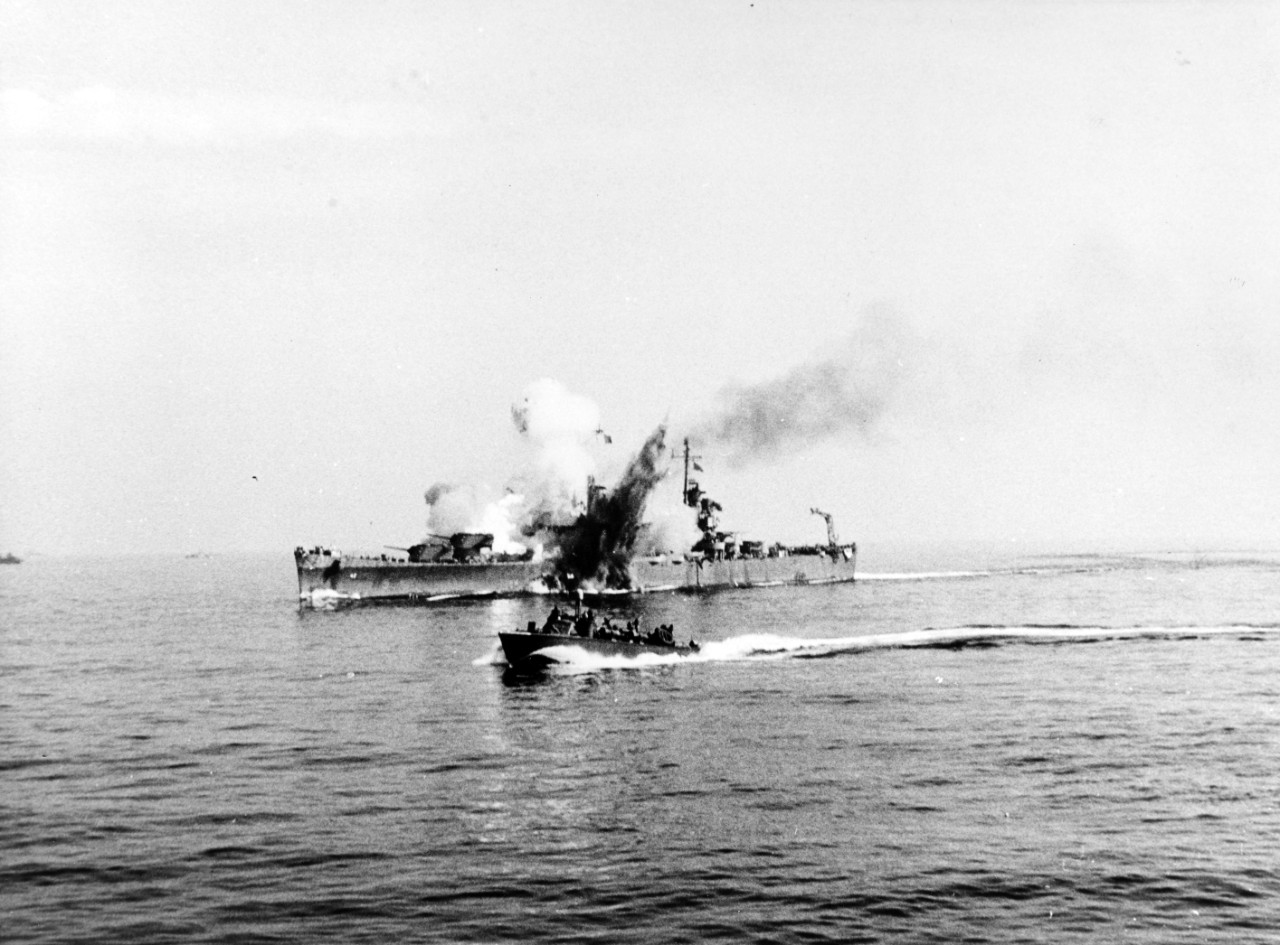

Savannah shot from 17,300 yards and sent 31 three-gun salvoes hurtling toward another battery (1806–1821) until the observer again radioed “area covered.” Allied officers sought to impede enemy movements and their ability to reinforce their troops, so an observer directed the ship to blast roads leading into the beachhead, and she responded from 12,650 yards with 23 three-gun salvoes (1842–1903). The sun set at 1924, and the cruiser moved out to the transport area to wait out the night.