Oglala (CM-4)

1917–1946

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the sixth of the original thirteen American colonies to be officially given statehood to the United States of America, which was granted on 6 February 1788. The commonwealth was named after the Massachusetts Bay Colony. King Charles I issued a royal charter to the Massachusetts Bay Company that established the colony , on 4 March 1629. The colony was named was for the indigenous people, the Massachusetts.

(Id. No. 1255, displacement 400; length 375'; beam 52'2"; draft 16'; speed 20 knots)

Massachusetts was laid down in 1907 by the William Cramp and Sons Ship & Engine Building Company at Philadelphia, Pa. for the Maine Steamship Company. Once construction was complete, she joined her sister ships Bunker Hill and Old Colony ferrying passengers between New York, N.Y., Boston, Mass., and Portland, Maine. In 1911, the Maine Steamship, Metropolitan Steamship, and the Eastern Steamship companies merged to create the Eastern Steamship Corporation. Massachusetts and Bunker Hill returned to the Cramp & Sons shipyard for conversion from coal to fuel oil in 1912. Financial difficulties forced Eastern Steamship Corporation into receivership in 1914 and it emerged three years later as the Eastern Steamship Lines. That same year, on 2 November 1917, Massachusetts and Bunker Hill were purchased by the Navy and sent to the Boston Navy Yard for conversion to minelayers. Massachusetts was commissioned on 7 December 1917, Capt. Wat T. Cluverius, in command.

Before Massachusetts completed her conversion she was renamed Shawmut, the name of the promontory on the St. Charles River that is home to Boston (you already located the city). She is the second ship in the Navy to carry the name. The name is believed to be a derivation of the Algonquian word mashauwomuk used by the local Massachusetts tribe of Native Americans. There are many different opinions over the literal translation of mashauwomuk. In The Indian Names of Boston, and Their Meanings (1886), Eben N. Horsford claimed the definition to be “canoe place.” Other scholars have translated it to mean “where they go by boat.” Her sister, Bunker Hill, was also renamed Aroostook (CM-3).

In April 1917, the Allies formulated a plan to lay massive minefields in the North Sea to counter German U-boat attacks on commercial and military ships in the Atlantic. Early studies indicated that the minefields should stretch between the northeast coast of Scotland, near Aberdeen, and the southwestern coast of Norway. Allied planners believed that this would effectively cut on the German submarines’ access to the Atlantic from the North Sea. President Woodrow Wilson approved the plan in October, and steps began to make the Northern Barrage a reality. This plan involved the creation of a new generation of minelayers of which Shawmut was included.

After her extensive conversion from a passenger steamer to a minelayer, Shawmut departed the Navy Yard at Boston on 11 June 1918. She completed her sea trails in Presidents Roads, Mass., before steaming to Naval Base 17 at Invergordon, Scotland. Prior to the Northern Barrage, the U.S. Navy Mine Force had been practicing laying and recovering mine fields off of the coasts of Long Island and New Jersey, often without public notification. The forces had also strewn anti-submarine nets in Chesapeake Bay, Long Island Sound, and the entrance of Narragansett Bay at Newport, R.I. The Navy had yet to deploy minefields of any scale as part of the war effort.

During sea trials, the evaluators discovered that Shawmut and Aroostook consumed fuel at a higher rate than expected. This bought about a great deal of concern that the new minelayers would be unable to make a non-stop trans-Atlantic voyage. Undeterred, Capt. Cluverius and Cmdr. Roscoe C. Bulmer devised a plan to refuel both ships while underway with hoses from the destroyer tender Black Hawk (AD-9). Although this technique was not commonplace at the time, and was done during a gale, both ships successfully refueled.

Shawmut anchored at Base 17 on 30 June 1918. Over the next several months the Mine Force busily planted mines in the North Sea along with their Allied counterparts. During this time period, Shawmut took part in ten minelaying excursions placing 2,970 mines for the barrage. From March to early November 1918, American and British ships laid 70,117 mines. With the cessation of hostilities on 11 November 1918, Shawmut loaded 310 mines from Base 17, and began her long journey back to the United States on 30 November. After a port call at Portland, England (5–14 December), she was underway with minelayers Quinnebaug (Id. No. 1687), Aroostook, Housatonic (Id. No. 1697), Saranac (Id No. 17020), and Canadaiqua (Id. No. 1694). After stopping at Ireland Island, Bermuda on 24 December, Shawmut returned to Hampton Roads Naval Operations Base (NOB), Norfolk, Va., on 27 December 1918.

No longer needed in peacetime to lay minefields, Shawmut returned to the Boston Navy Yard to be refitted for a new mission. She was reassigned to the U.S. Air Detachment to serve as an aircraft tender. The ship carried out the majority of her duties tending the amphibious aircraft off the eastern seaboard of the United States from Key West, Fla., to Narragansett Bay, R.I. Her voyages frequently took her to foreign ports including: Guantánamo Bay, Cuba; Kingston, Jamaica; Samana Bay, Dominican Republic; and Trujillo, Panama. On 17 July 1920, she was reclassified to CM-4. In June and July 1921, Shawmut participated in an event that is a major milestone in military aviation history.

World War I had introduced the use of aircraft to military operations and naval aviation was also still in its infancy. Brig. Gen. William Mitchell, USA, had emerged as an outspoken advocate for the use of aircraft in military operations. Although the use of airborne platforms, such as hot air balloons, blimps, and dirigibles gained increasing acceptance among the armed forces of the world, winged aircraft were a new technology whose effectiveness as a weapon had yet to be proved. While serving in France during 1917, Mitchell encountered Sir Hugh Trenchard, commander of the Royal Flying Corps. Trenchard held the belief that an independent air force could be a highly effective weapon against an enemy. In September 1918, when he led 1,481 American and Allied aircraft, Mitchell effectively put Trenchard’s concept into action. At St. Mihiel, France, American and Allied planes decimated their German counterparts to establish air superiority, and then proceeded to take part in the destruction of the German forces on the ground. For his actions during the war, Mitchell received multiple accolades for foreign governments, along with the Distinguished Service Cross and the Distinguished Service Medal from the U.S. Army.

After the war, Mitchell continued to argue for the establishment of an independent air force and expanding the use of winged aircraft. His undiplomatic style failed to win over his colleagues. One long held belief was that aircraft would be ineffective as weapons against contemporary military vessels. Mitchell was determined to prove them wrong.

In the summer of 1921, a series of bombing exercises were scheduled to take place in the Hampton Roads off the coast of Virginia. As part of the effort to document the first of these exercises, two U.S. Army photographers from Langley Army Air Field were embarked in Shawmut on 20 June. At 0400 the following morning, she lay close to the captured German U-boat, U-117, that was to be used as the first target. Four hours later she began to steam circles around the intended target. Approximately two hours and twenty minutes later three airboats, No. 74, No. 92, and No. 94 appeared into view. The aircraft began their bombing run at 1022 then returned for a second run at 1031. Seven minutes later, U-117 slipped beneath the waves.

The bombing test continued in July 1921 using three former German warships; the destroyer G-102, light cruiser Frankfort, and the battleship Ostfriesland. The first to meet the bombers was G-102 on 13 July 1921. At 0930 11 Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5, 15 Martin MB-1, 15 Airco DH.4 bore down on the ex-destroyer along with three Army dirigibles. G-102 sank to the bottom an hour and ten minutes later. Five days later (18 July), Frankfort was dispatched to the deep when Army MB-1s scored two direct hits on her. She disappeared below the surface in thirty minutes. The grand finale of the test came against Ostfriesland on 21 July.

Although the Navy had requested that restrictions be placed on the pace of the bombing of Ostfriesland, Mitchell had the Army press a full and immediate attack. The first attacks were made by aircraft carrying 1000 pound bombs and second wave of aircraft armed with 2000 pound bombs. Although there were no verified direct hits on the ship, she sank in twenty minutes as a result of the bombing. Navy officials lodged formal protest that the pace of the attack prevented their engineering experts from examining the damage to the ship. Despite the controversy, Mitchell had proven his supposition that land based aircraft could be deadly when used against enemy ships far at sea. Mitchell’s career continued to be filled controversy from stating that the Pacific Fleet was vulnerable to attack from the air by Japan and accusing his superiors to be incompetent. He was later convicted by a court-martial for insubordination and suspended from active duty for five years without pay. Mitchell chose to resign instead in February 1926.

After participating in the bombing exercises, Shawmut returned to her routine as an aircraft tender for the rest of summer of 1921. She entered the Philadelphia Navy yard for an overhaul on 31 October where she remained until 5 January 1922. In the New Year, she returned to her primary duties as a minelayer but also continued to provide services to Navy planes. Her duties took Shawmut back to the Caribbean as well as operating along the U.S. east coast for battle practice, gunnery and mining exercises. In early November 1922, after she had finished maintenance and repair at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Shawmut was ordered to Honduras for a mission of diplomatic importance.

On 1 November 1922, Dr. Don J. Antonio Lopez Gutierrez, Ambassador to the United States for Honduras, passed away in Washington, D.C. Shawmut was moored at Hampton Roads NOB (9–11 November) while members of her crew attended radio school. On 11 November, she embarked the body of Ambassador Gutierrez, and his son Lopez Gutierrez, with orders to carry the deceased to Honduras. She arrived at the Panama Canal on 18 November where American and Honduran dignitaries serving in Panama paid their respects in placing wreath on the casket. After transiting the canal, Shawmut proceeded to Amapala, Honduras for the official state funeral (22 November 1922) that was attended by his brother, Rafael López Gutiérrez, the President of Honduras. The deceased was returned to Shawmut and then taken to the Ambassador’s final resting place at La Libertad, El Salvador (22–23 November). Shawmut then reversed her course getting underway to return to Philadelphia for more upkeep and repair (6 December 1922–3 January 1923).

In February 1923, Shawmut retuned to Panama making a port call at Fernandina (13–19 January), then visited Key West (21–28 January) as well as Belize, British Honduras (30 January– 5 February 1923). She transited the Panama Canal from Bocas del Toro to Balboa, Panama, on 15 February.While at Panama, Shawmut participated in battle practice and tactical movement exercises in the Gulf of Panama. She also took part in exercises testing an experimental practice torpedo designed to help ships sharpen their targeting skills.

On 6 April 1923 Shawmut set out for Philadelphia (8–26 April) where she was reassigned to Mine Squadron One of the U.S. Scouting Fleet (1 March 1923). As a member of the Scouting Fleet, she began a continual cycle of training operations and deployments along the Eastern United States, the Caribbean Sea, and the Gulf of Panama at Balboa. Her operations along the U.S. coast typically involved the deployment and recovery of minefields in the Chesapeake and Ipswich bays. While operating in the Caribbean, Shawmut’s duties involved tending aircraft, gunnery drills, tactical maneuvers, and participation in fleet scale exercises. Quite often her crew was treated to liberty at locations such as St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, Kingston, Guantánamo, and Havana, Cuba. She also made annual deployments back to Balboa and the Gulf of Panama for battle practice and to participate in torpedo targeting training exercises. In November 1924, Shawmut began annual visits to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md., to use the academy rifle range to sharpen her crew’s small arms skills. Her presence also provided the opportunity for Midshipmen to witness life onboard an active minelayer and aircraft tender. These visits where usually topped off by several days of liberty in Baltimore, Md., before returning to her routine.

In April 1925, there was a break in Shawmut’s typical schedule. On 3 January, she was underway to Pearl Harbor, T.H., via the Panama Canal (18 January) and San Diego, Calif. (9 March) for the first time. She departed San Diego on 4 April 1925 for Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii (T.H.) after a brief visit to San Francisco, Calif. (5–15 April). The battleship Wyoming (BB-32) accompanied her on the voyage to Hawaii. She reached Pearl Harbor on 28 April and remained in port until 7 May. For nearly the entire month of May, Shawmut was at sea steaming with the Pacific Fleet (8–30 May) before putting into Hilo, T.H., on 31 May. After a brief return to Pearl Harbor, she was underway steaming back to San Diego (17–22 June) and Balboa (3–5 July) before mooring at Boston (13 July 1925) for maintenance and repairs.

After her maintenance was completed at Boston, Shawmut returned to her routine schedule once again with limited variation for the next two years. On 1 October 1927, she returned to Boston to undergo an extensive overhaul and engine modifications. Her engine changes involved the installation of a new boiler system that also modified her exterior appearance. With the new changes installed, Shawmut emerged from the yard on 30 November 1927 with a new single stack instead of her original twin stacks. It was also during that time frame that a situation arose that facilitated another change. It had been determined that her name might easily be confused in communications with the transport Chaumont (AP-5). In October, Adm. Edward W. Eberle, Chief of Naval Operations, forwarded his endorsement of the recommendation that Shawmut’s named be change to Oglala -- the name of a sub-band of the Lakota Nation, more commonly known as the Sioux Nation -- to Secretary of the Navy Curtis D. Wilbur, who approved the change, effective 1 January 1928.

The Oglala are members of the Lakota Nation most commonly known as the Sioux Nation. The nation consists of seven large bands known collectively as the Seven Council Tribes, Očhéthi ŠakŠówiŋ. The Oglala are a sub-band of the Thítȟuŋwaŋ, People of the Plains, who once occupied a large area around the Black Hills of South Dakota. Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Red Cloud are probably the most well know members of the Oglala band. The aforementioned are mostly known for leading the indigenous resistance to the American western expansion during the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. It was during this conflict that the 7th Cavalry Regiment, under the command of Lt. Col. George A. Custer, was decimated at Little Bighorn. In 1877 Crazy Horse was arrested by the US Army in northwest Nebraska with the assistance of his former allies American Horse and Red Cloud. He was later killed trying to escape from Fort Robinson on 5 September 1877. Sitting Bull was killed on 15 December 1890, during a dispute with Indian agents over the performance of the traditional “Ghost Dance,” at Standing Rock Reservation.

In subsequent years the Lakota territories were slowly eroded from the boundaries established by the Treaty of Laramie (1851). The Oglala were eventually placed on the Pine Ridge Reservation in southwestern South Dakota. The people that once occupied great swathes of land were relegated to dwell upon 3,500 square miles. The Oglala still remain at Pine Ridge where they struggle to maintain their language, traditions, and culture.

On 1 January 1928, the newly renamed Oglala was underway from Boston to the Gulf of Panama (10–16 January). Although she carried a new name and a new look, her routine continued as before. She steamed between Boston and Balboa, to the Caribbean and along the U.S. east coast planting and recovering her mines. She continued this pattern until 1931 her home port was shifted to Pearl Harbor. Oglala transited the Panama Canal on 31 January to participate in a fleet exercise (17–22 February 1931) along the western coast of Central America before proceeding to San Diego (23 March). After two weeks in port, she was underway to her home with submarines S-23 (SS-128), S-22 (SS-127), S-25 (SS-130) and the minesweeper Lark (AM-21) on 25 April 1931. Upon her arrival, she was assigned to the Minecraft Battle Force of the Pacific Fleet.

Just as when she was operating with the Atlantic Fleet, Oglala’s schedule settled into a fairly regular routine for the next several years. She continually engaged in battle practice, gunnery exercising, and mining rehearsal between the islands of Hawaii, Oahu, Maui, Kauai, and French Frigate Shoals. Oglala also participated in three joint Army-Navy exercises during on 31 October–1 November 1932, 28–29 March, and again on 18 August 1933. In January 1934 she underwent an overhaul until 28 March. Oglala spent several days conducting mining operations off Oahu (1–7 April 1934), and then continued her overhaul in the Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash.

After the completion of her overhaul on 11 May 1934, Oglala got underway to the Bering Sea to take part in the 1934 Aleutian Island Survey Expedition under the command of Rear Adm. Sinclair Gannon. Oglala, along with oiler Ramapo (AO-12), minesweepers Kingfisher (AM-25), Gannet (AM-41), Swallow (AM-4), Quail (AM-15), and Tanager (AM-5), placed sounding stations on several Aleutians to conduct hydrographic surveys. The conditions in the Bering Sea did not always prove hospitable to their efforts, and ships often postponed their operations due to hazardous weather. Oglala also tended planes that participated in the survey expedition.

Although the weather often hampered operations, the conditions in the Aleutians proved very hazardous even on good days. On 18 July 1934, one of Oglala’s dinghies carrying six sailors was caught in heavy surf near Igitkin Island. The small boat capsized and the occupants were tossed into the sea. The bluejackets scrambled ashore but they were by no means out of harm’s way. Oglala immediately dispatched her motor whale boat to rescue her crewmen. The castaways were safely recovered and an attempt was made to retrieve the dinghy. It was determined the boat was beyond repair after being repeatedly bashed against the rocky shore. The rescue party returned to Oglala without the dinghy. Back on board, the men were examined by the ship’s medical staff. The ship’s medical people treated the sailors for exposure to the elements.

It was not all work for the men of the expedition. Even the senior officers were given opportunities to embark on their own adventures. On 29 July 1934, Rear Adm. Gannon, accompanied by Oglala’s commanding officer, Capt. William T. Mallison hiked 1,000 feet to the rim of the Kasatochi Volcano. Once the men reach the top, they discovered the crater held a tiny lake.

The enlisted men also shared some adventures but not all ended as planned. While on a recreational hike on Great Sitkin Island (30 July), one of Oglala’s sailors lost his footing and fell off a cliff. A medical officer was sent ashore to treat the injured man, who suffered from shock and multiple contusions and lacerations, the most serious of which was a slice to his scalp that required stitches. He was returned to Oglala and placed in the infirmary. That same day, several men failed to return to Oglala after hiking on the island. At 2108, two of the missing men were spotted on shore and returned to the ship. The men stated that they became lost in low cloud cover and were unable to locate the pathway leading to the designated beach to be picked up. The search for the remaining sailors continued into the night. To help guide them, the search party started a signal fire on beach. By 0545 the next day, the remaining hikers had been located and were safely in Oglala. Their accounts echoed the statements of the other men claiming low clouds or fog had caused them to become lost.

On 6 September 1934, Oglala’s first Aleutian expedition came to a close and she was underway to Bremerton. By mid-October, she settled back into her regular routine at Pearl Harbor. Oglala underwent maintenance at Puget Sound (1 March–23 April 1935) and then returned to the Aleutians on 2 May 1935. She spent the first month tending planes before participating in her second survey expedition for two months with Gannet, Kingfisher, Tanager, and Quail. Oglala returned to Puget Sound (5 August) before getting underway for Pearl Harbor (18 August 1935). Beginning on 1 September 1935, she completed maintenance and repair for the rest of the year, with the exception of a brief visit to Lahaina, T.H. (departing from Hawaiian waters on 2 December 1935).

After spending the first three months of 1936 either in port at Pearl Harbor or involved in battle practice at Lahaina (22–24 January), Oglala got underway for Pearl and Hermes Reef, T.H., to conduct hydrographic surveys (31 March) accompanied by Minecraft Battle Force. Although this survey was conducted in a warmer, more hospitable climate, it was not without hazards (6–17 April 1936). On the second day of the survey (7 April), one of the participating aircraft clipped one of its wings on a sounding platform mounted on a motor launch from Quail. The plane came to rest on nearby Green Island, Kure Atoll, T.H. The impact cut away one of the platform support members which struck a sailor manning the station in the head causing a contusion. The crew of the aircraft suffered no injuries. With the survey concluded, Oglala returned to her usual duties operating throughout the Hawaiian Islands before entering the shipyard at Pearl Harbor for another overhaul on 1 January 1937.

Oglala completed her overhaul in late April 1937. After finishing see trails in May, she was returned to full duty in June. On 4 October, Oglala had returned to Puget Sound for more maintenance and upkeep (4 October–2 November) then proceeded to the Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif., to continue her repairs (5 November–12 December 1937). Steaming with Minecraft Battle Force, Oglala returned to Pearl Harbor on 20 December in time to celebrate the holidays.

In 1938, a new task was added to Oglala’s routine. In addition to the usual battle practice, gunnery drills, mining operations, etc., Oglala made her first voyage to Midway Island, T.H. (18 April) to deliver passengers and cargo. She made several journeys to Midway in 1939. In 1940, she added Johnston and Palmyra islands to her cargo and passenger circuit (10–20 June 1940). In between her new task, Oglala participated in exercises (15–20 April 1940) and tactical maneuvers (10–14 September 1940). She ended 1940 in port at Pearl Harbor following a brief visit to Kahului, T.H (4–5 December).

Oglala began 1941 undergoing maintenance and upkeep (1–29 January) before returning to her usual duties. Perhaps due to the increasing threat of the Japanese Empire, by mid-Summer her voyages to the western extremes of American territory had steady deceased. In July 1941, she began to operate mostly in the operational areas close to main islands of the Hawaiian territory and conducting mining training in Pearl Harbor. In the late fall, Oglala steamed to San Francisco for maintenance (30 October–12 November 1941). With the approach of the holiday season, Oglala remained moored at Pearl Harbor after returning from San Francisco.

On the morning of 7 December 1941, Oglala lay moored outboard of light cruiser Helena (CL-50) alongside Ten Ten Pier, Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. Around 0755 on that bright blue Sunday morning, she was called to general quarters. Her sailors immediately manned her guns and began firing on the attacking Japanese aircraft. An enemy Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 carrier attack plane bore down at a low altitude and released a torpedo toward her midships. The weapon detonated near her port side in between Oglala and Helena, rocking her violently. The blast ruptured her port hull and lifted fireroom floor plates, causing her to immediately take on water. Almost simultaneously, Japanese planes strafedOglala. Since the ship was receiving power from the dock, the crew was unable to start her pumps to fight the deluge. Approximately five minutes into the attack, a bomb fell into the water between Oglala and her companion cruiser, detonating near her fireroom. With the lack of power to run the pumps and the rate at which she was flooding, it became clear the Oglala would not remain afloat. The ship began to list five degrees to port. Cmdr. Edmund P. Speight, her commanding officer, was ashore and Cmdr. Roland E. Krause, the executive officer, had taken command and he decided to move the ship clear of Helena and secure her directly to the pier. Although Helena had been severely damaged, her crew prevailed and kept her afloat, and by around 0900 secured her aft of Helena. Thirty minutes later her list had increased to twenty degrees and the order was given to abandon ship. Sometime around 1000, she rolled toward the dock knocking off her bridge structure and main mast as she settled to the bottom on her port side. Oglala remained in that position while the Pacific Fleet began preparing to take the fight to the Japanese.

Despite the fact that the Japanese had sunk Oglala, thankfully none of her crew was killed in the attack. Only three of her sailors received injuries. The most seriously injured was Sea1c Howard A. Poler. While in the ship’s Bake Shop, Poler was shot through the face while securing the fires in the bake oven. Sea1c “R” “J” Hodnett received wounds to his right hip by fragments of an explosion. The third crewman to be injured was not on Oglala at the time. CM3c Lowell Powellwas hit in the right knee with a shell fragment while helping man a 3-inch anti-aircraft battery on board the battleship Pennsylvania (BB-38).

In his after action report, Cmdr. Speight commended the entire crew for performing in accord to the “highest tradition of the Navy,” but particularly singled out two sailors. F2c Jerald "E" Johnson took decisive action in the immediate aftermath of the attack. Johnson secured the boiler and fireroom preventing the chance of a boiler explosion and curtailing some the flooding of the ship. CBM Anthony Zitowas able to quickly get Oglala’s 3-inch anti-aircraft gun into action to fire on the approaching Japanese planes. After the order was given to abandon Oglala, Zito commandeered a drifting motor launch and two of his shipmates then sped to give assistance to the ships on Battleship Row.

Oglala lies on her side following the devastating Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, T.H., on 7 December 1941. (Unattributed U.S. Navy Photograph 80-G-32537, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, Md.)

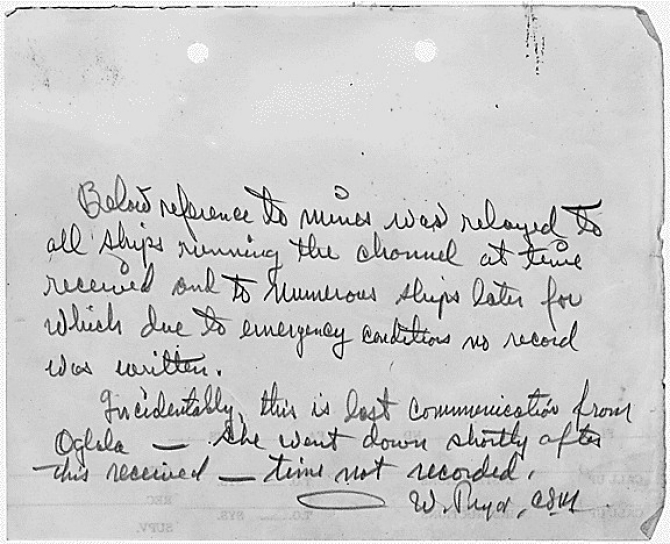

The ship sends this final message on that fateful day. (Unattributed U.S. Navy Photograph 37-0763a, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, Md.)

The effort to salvage Oglala began on 12 December 1941. The first attempt to refloat her by blowing compressed air into her hull proved to be ineffective. Several plans for her future were considered including floating her enough to drag her ashore. Once on dry land, she would be dismantled. After a reexamination of the situation, a plan was formulated to raise and refit her. By the early spring of 1942 the salvage operation was underway. It was decided that using ten 80 ton submarine salvage pontoons in concert with anchor chains and the aforementioned air bubble technique to right her. The hope was that Oglala could be brought to rest on her bottom. At low tide, she would still be lying in approximately 45 feet of water, and a 10 degree list, but the salvage work could begin in earnest. A date of 11 April 1942 was set to begin inflating the pontoons and begin the process. On 22 April, the crane barge Gaylord, of the Hawaiian Dredging Company, was rigged to Oglala to pull her over, if needed, as she was righted the following day. The operation was a success and Oglala came upright to rest on her bottom.

In June 1942, the reconstruction of Oglala began. Finally, on 23 June, after six months with her port side beneath the surface, she was floated. The salvage crew was unable to bring her to the draft depth required by the keel blocks in the dry dock, however, and the ship was unsteady. Work began to increase draft and improve her stability but she faced another stumbling block. During the night of 25–26 June 1942, the pumps fighting to keep Oglala afloat were overwhelmed by an influx of water and she settled to the bottom again. An investigation revealed that the fuel line for the main gasoline powered pump had become clogged overnight. There was an electrical back-up pump but the water level did not rise high enough for it to be effective. While attempting to refloat her again on 29 June, a failure to the cofferdam in aft section caused her to settle down again. It was determined that the field crew had not built the cofferdam to the proper specifications. It was the second time this costly mistake had been discovered. The cofferdam was removed, repaired properly and reinstalled within 24 hours. She was floated for a third time on 1 July. Sadly her dockside troubles were not behind her. On the same day, sometime between 1815 and 1830 while the pump in her bow was being refueled, gasoline was spilled on the hot exhaust manifold causing a flare-up. This resulted in fuel being splashed on the bow cofferdam and an open five gallon fuel bucket to be dropped in the water. The fire watch on board responded quickly as did the crew of the submarine rescue vessel Ortolan (ASR-5), the yard fire department, and men from other surrounding ships. The effort extinguished the blaze in 30 minutes, before it could cause any serious damage. When Oglala was finally towed to the dry dock, the bow was the only part of her above the waterline. Once she was settled into the keel blocks, the refitting work began.

On 23 December 1942, Oglala was sea worthy and underway to Mare Island (2 January1943) where she remained as her reconstruction plans were finalized. Once her plans were complete, she stood out of San Francisco Bay for the shipyard at Terminal Island Naval Dry Docks, Calif. (23 January). When she arrived there (25 January 1943), Oglala remained moored at Terminal Island awaiting availability in the shipyard. After lying sedentary for the entire month of February, she was moved into the shipyard on 1 March 1943. Upon entering the shipyard, Oglala’s days as a minelayer came to a close. Her refitting included a complete conversion into an engine repair ship with a tentative completion day of 1 February 1944. On 15 June 1943, Oglala was reclassified to an internal combustion engine repair ship (ARG-1). While she was undergoing conversion, Oglala remained assigned to Mine Squadron (MinRon) 1 in the Service Squadron (ServRon) within the Pacific Fleet. In November she received word that her assignment would be shifted to the Seventh Fleet when she completed converting.

Due to construction delays, Oglala’s conversion missed the initial completion date of 1 February 1944. She had been scheduled to begin dock trails on 17 February, but the lack of progress by the construction crews caused them to be cancelled. On 28 February she was moved under tow to a berth at the Naval Supply Depot, San Pedro, Calif., to begin loading the ship’s stores and continue the conversion. She began preliminary acceptance dock trials on 2 March. Oglala was accepted into service on 16 March. After completed her sea trials (21–26 March), she reported ready for duty on 30 March and was independently underway to her new home at Milne Bay, New Guinea the following day. Oglala reported for duty at Milne Bay on 24 April and began receiving ships alongside for repair work on 29 April.

In the wake of Operations Reckless and Persecution in the late spring (May–June 1944) that pushed the Japanese out of Hollandia, New Guinea, Oglala got underway in the early dawn hours of 1 July to provide repair services at Humboldt Bay, New Guinea. That night, at 2200, Oglala’s radar picked up several small vessels off of her port bow at approximately 3300 yards. Thirteen minutes later the boats where 200 yards off of her port beam. It appeared as if they would pass clear. Suddenly the lead craft made a turn to port and attempted to cross Oglala’s bow. Oglala put her rudder hard to port and her engine to full stop in an attempt to avoid a collision. One of the picket boats struck her stem and a mechanized landing craft (LCM) struck the port bow frame. The LCM capsized, dumping her occupants into the sea, and the picket boat sank in approximately one minute. Oglala dispatched her whale boat and trained floodlights on the water to search for survivors. The whaleboat returned with 1st Lt. J.T. Barron, USA, of Company B, 533rd Engine Boats and Shore Battalion, who informed Oglala’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Henry K. Bradford, that all of the men were safely pulled from the water. Barron was asleep in the picket boat at the time of the collision and could not provide an explanation as to why it made a sudden course correction. The formation was underway to Milne Bay from Finschhafen, New Guinea. The young officer was provided with new navigation charts having lost his copies when the picket boat sank and sent on his way. Oglala safely arrived at Humboldt Bay on 6 July 1944. She shifted her berth to Imbi Bay at Hollandia the next day.

With more successful Allied campaigns moving the Japanese off of more territory, Oglala was underway once again to provide support. On 14 December, in the waning days of the Battle of Leyte (17 October–26 December 1944), she was ordered to San Pedro Bay, Leyte, Philippine Islands. Oglala lay at San Pedro Bay, tending various types of small craft, when she received word of the Japanese surrender, on 15 August. She remained in those waters until ordered to return to San Francisco in January 1946.

On 9 January 1946, Oglala sailed for the U.S., setting course to proceed via Guiuan, Philippines (10 January) and Pearl Harbor (30 January–2 February 1946). She dropped anchor in San Francisco Bay on 10 February 1946. Upon her arrival Oglala was attached to the Assistant Industrial Manager, Western Sea Frontier, Service Force, Pacific Fleet, for decommissioning. On 28 March 1946, infantry landing craft LCI-43, LCI-704, LCI-706, and LCI-808 came alongside to begin striping her of material in preparation to join the National Defense Fleet, Suisun Bay, Calif. Five months later, the venerable vessel’s official life came to a close when she was decommissioned on 8 July 1946. She was stricken from the Naval Register on 11 July 1946. As his last official duty as a member of the Oglala crew, Lt. James T. Gehrig accompanied her as she was towed to Mare Island.

Transferred to the Maritime Commission on 12 July 1946, the day after she was stricken, Oglala remained with the “mothball fleet,” berthed in the Reserve Fleet at Suisun Bay, Calif., for almost two decades. She was sold to Nicolai Joffe Corp., Beverly Hills, Calif., on 2 September 1965 to be broken up for scrap.

Commanding Officers |

Date Assumed Command |

Capt. Wat T. Cluverius |

7 December 1917 |

Capt. George W. Steele Jr |

3 February 1919 |

Cmdr. Damon E. Cummings |

27 April 1919 |

Capt. George W. Steele Jr |

17 June 1919 |

Capt. Alfred W. Johnson |

1 September 1920 |

Capt. William D. Leahy |

24 December 1921 |

Capt. John W. Greenslade |

30 June 1923 |

Capt. Harry. L. Brinser |

17 June 1925 |

Capt. William S. Pye |

2 May 1927 |

Capt. Donald C. Bingham |

5 December 1928 |

Capt. Joseph V. Ogan |

15 November 1930 |

Capt. Paul E. Speicher |

14 April 1931 |

Capt. William. T. Mallison |

21 June 1932 |

Capt. Francis Cogswell |

12 September 1934 |

Capt. Roy C. Smith |

10 June 1936 |

Lt Cmdr. Fred W. Connor |

3 May 1937 |

Cmdr. John W. McClaran |

25 June 1937 |

Cmdr. James G. Atkins |

26 June 1939 |

Cmdr. C. D. Edmunds |

13 February 1941 |

Cmdr. Edmund P. Speight |

18 April 1941 |

Cmdr. Henry K. Bradford |

30 June 1942 |

Lt. Cmdr. Alfred Nelson |

5 May 1945 |

Lt. Henry H. Frye |

20 December 1945 |

John W. Watts, Jr 19 December 2016