McDougal I (Destroyer No. 54)

1914-1934

David McDougal -- born in Ohio on 27 September 1809 -- was appointed midshipman on 1 April 1828 and accepted his appointment on 29 May of the same year. He received orders to report to Commodore Isaac Chauncey at the Naval School in New York in August 1830 and again to report to the Commodore for service on board the sloop of war Boston in the Mediterranean squadron in April 1831. On 4 September of the same year, McDougal reported to the frigate Brandywine where he served on the ship as it transported U.S. envoys to Naples in an attempt to recoup indemnities owed to the United States by the kingdom for seizure of U.S. ships during the Napoleonic wars. After returning to the U.S. and taking leave he returned to naval school in Brooklyn on 4 October 1833. He sat for an examination of midshipmen at Baltimore in May 1834 and returned to New York by order of the President of the Board of Examiners. In June 1834 he was warranted passed midshipman.

After a long stint of leave, McDougal reported on board Natchez of the West Indian squadron on 1 July 1836, and operated in the Caribbean. While on board Natchez he dove into shark infested Pensacola harbor order to save a man who had fallen overboard. His next station was the schooner Grampus on 30 November 1838, an assignment that kept McDougal in the Caribbean. In March 1839 he was ordered to duty on board the navy receiving ship North Carolina at New York. Following this station he reported to the brig Consort in December 1839 preparing to engage in a survey of southern harbors. He continued with these duties until October 1840 when he detached from the brig in order to construct charts from the surveys. After completing this assignment in February 1841, McDougal earned appointment to lieutenant on 25 February.

On 19 May 1841, the new lieutenant was ordered to report to Commodore James Renshaw for duty on board the steamer Fulton. He had a short stay on the steamer ended by orders to report to Commodore Matthew C. Perry and serve on board Falmouth on 6 December 1841. The lieutenant stayed in the sloop of war Falmouth as she sailed with the Home Squadron until returning to New York due to ill health in March 1843. After a short return to Falmouth, McDougal travelled north to the Great Lakes to serve in the steamer Michigan.

McDougal was still attached to Michigan when Congress declared war on Mexico on 13 May 1846. In January 1847, the officer was detached from the lake steamer to serve on board the side-wheel frigate Mississippi of the Home Squadron. In March, Mississippi participated in the blockade and later siege of Vera Cruz when sailors manned naval guns dispatched to the Army’s siege works surrounding the city. In late April, she also participated in the expedition against Tuxpan, destroying the fortresses near the town and recovering the earlier captured guns of the stranded and burned American brig Truxtun. McDougal’s war ended in June 1847 with an ankle injury that sent him home.

In February 1848, Lt. McDougal reported to the sloop-of-war St. Mary but transferred to the brig Bainbridge one month later. Bainbridge engaged in anti-slave trade patrols off the coast of Africa. He was detached from that ship, and after a year of leave and awaiting orders, he returned to Michigan on the lakes. From the Great Lakes, the Department of the Navy authorized him to make the long voyage to San Francisco on 6 February 1854 to take command of the station ship Warren. McDougal ultimately reached Mare Island Navy Yard on 10 August where the ship tied up.

From February to August 1856, McDougal commanded the steam tug John Hancock. The vessel steamed in support of the war fought by Washington Territorial Militia and U.S. Army troops against Native American tribes in the vicinity of Puget Sound. On 24 January 1857, Lt. McDougal was promoted to commander after nearly 30 years of service.

Following the outbreak of the Civil War, Cmdr. McDougal was detached from Mare Island and ordered to New York. On 27 May 1861, the Navy named him commanding officer of the steam frigate Wyoming, a post that he assumed on 9 August. On 16 June 1862, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles ordered the veteran officer to the Far East with Wyoming, to guard against Rebel attempts to attack trade in the Far East and the East Indies and transport the new Minister of Japan to his station.

Word of the Union ship’s subsequent appearance in Far Eastern waters spread fast and far. In the Strait of Sunda, off Java, Capt. Raphael Semmes, the commanding officer of Confederate cruiser Alabama, learned from an English brig of Wyoming’s arrival in the East Indies; and a Dutch trader later confirmed this report. On 26 October, Semmes wrote confidently in his journal that “Wyoming is a good match for this ship,” and “I have resolved to give her battle. She is reported to be cruising under sail—probably with banked fires—and anchors, no doubt, under Krakatoa every night, and I hope to surprise her, the moon being near its full.”

Although Wyoming and Alabama unknowingly came close to each other, they never met, and it would be up to another Union warship, the sloop Kearsarge, to destroy the elusive Confederate raider. Yet, despite being unsuccessful in tracking down Confederate cruisers, Wyoming did render important service to uphold the honor of the American flag in the Far East in 1863.

While the U.S. was embroiled in a Civil War, the Feudal dominions of Japan were undergoing their own internal struggle. The Tokugawa Shogunate that had ruled Japan for over 250 years was challenged by rebellious clans that wanted to invest power in the previously apolitical Japanese Emperor, and expel all foreigners from Japanese territory. In May 1863, Wyoming lay at the port of Yokohama, the locus for foreign trade with Japan, to protect American lives and property against anti-western agitation.

Outside of Yokohama, however, the situation was worsening for foreigners in Japan. The Daimyo, or feudal lord, of the Mori clan who ruled the Choshu domain was among the most ardent supporters of the Emperor and expulsion. The Choshu domain also held a commanding position on the northern bank of the Shimonosheki Straits, an important waterway for navigation from the west to China, Korea and east to the Japanese inland sea and the wider Pacific. When the Emperor issued a decree expelling all foreigners from Japan, the Daimyo resolved to deny the straits to foreign ships.

At 0100 26 June 1863, one day after the decree to expel foreigners took effect, Choshu vessels illegally flying the colors of the Shogunate fired on the U.S. merchant steamer Pembroke in the straits. No one was injured on the vessel and she escaped, continuing to Shanghai. Choshu forces using shore batteries and American-gifted vessels later fired on French and Dutch warships, driving the western vessels from the straits. The news of the attack on Pembroke reached Yokohama from Shanghai on 10 July. Cmdr. McDougal conferred with the U.S. minister resident to Japan, and they agreed that the offense to the American colors should be avenged and further aggression deterred by a show of force. Wyoming stood out for the straits on 13 July arriving at the eastern end on the morning of 16 July.

At 10:45 a.m., Wyoming entered the straits, greeted by an alarm raised from a signal gun. Choshu batteries began firing when she came within range as Wyoming ran up her colors. The Daimyo’s strength soon presented itself, six batteries of artillery on shore and three vessels, a steamer, a brig and a bark preparing to get underway close to shore. The intrepid sloop steamed directly for the enemy vessels under fire from both sea and shore. She returned fire at the batteries along the way and inflicted damage on several.

McDougal took a treacherous route through the straits, ordering his ship close to shore in order to foil the Choshu batteries trained on the typical mid-channel route. The wisdom of this decision was readily apparent by the torn up rigging above the her deck. After aggressively maneuvering between the brig and bark on the starboard side and the steamer on the port, the risky course seemed to backfire when after trading broadsides with the brig, Wyoming ran aground.

With the American caught in the shallows, the Japanese steamer began to get underway to join the battle. The U.S. vessel freed herself from her predicament in time to put two 11-inch shells and a 32-pound shot into the steamer, exploding her boiler, disabling her and leaving her in sinking condition. The gun crews also placed several shots into the bark causing serious damage as the crippled brig slowly settled into the water. With the steamer and brig in sinking condition and the bark effectively rendered harmless, Wyoming steamed back past the weakened batteries and out of the channel.

The battle lasted seventy minutes, four sailors on board Wyoming died and seven were wounded, at least one who later died of his wounds. The ship was hulled 11 times and there was extensive damage to the rigging and smokestack. The steam sloop’s guns, however, had delivered a serious blow to the Daimyo as the first foreign ship to take the offensive to uphold treaty rights in Japan. Commander McDougal wrote in his report to Gideon Welles on 23 July, “the punishment inflicted and in store for [the Daimyo] will, I trust, teach him a lesson that will not soon be forgotten.” While the Daimyo had cause to remember McDougal’s actions, many in the U.S. took little notice with the Civil War at its height.

Wyoming continued to search for Alabama and other Confederate raiders throughout the Pacific without any success. During this epic search he was commissioned captain from 2 March 1864. By February 1864 the worn state of Wyoming’s boilers compelled the ship to return to the East Coast for repairs, arriving in Philadelphia 13 July 1864. The commandant at Philadelphia ordered the weary crew back to sea immediately to search for the CSS Florida, reported off the East Coast. After five days, however, the ship’s leaky boilers forced the sloop back to Philadelphia on 19 July. Capt. McDougal was detached from Wyoming the following day.

On 26 July 1864, McDougal obtained permission from the Navy to return to California. After a period of leave he again took command of the Navy Yard at Mare Island. He was relieved of this duty in the summer of 1865 and took command of the steamer Pensacola of the North Pacific squadron in April 1867. McDougal detached from Pensacola on 17 July 1867. He was in command of the Sloop Jamestown at Sitka, Alaska, on 18 October 1867, when the Russian flag was hauled down at the Government House and replaced by the Stars and Stripes in a ceremony attended by troops and dignitaries of both nations. The action signified the transfer of the former Russian colony to the U.S. as the Department of Alaska.

On 14 January 1868. McDougal assumed command of the side wheel steam frigate Powhatan, Rear Adm. John Dahlgren’s flagship of the South Pacific Squadron, and on 12 June 1869, he was promoted to commodore. In December of the same year, he relieved Dahlgren and took command of the South Pacific Squadron. On 27 September 1871, he was placed on the retired list. Detached from command of the South Pacific Squadron and returned to his residence in Oakland, Calif. On 5 July 1876, he was commissioned rear admiral on the retired list.

On 7 August 1882, McDougal died at his residence in South Park, San Francisco, and was buried in the Mare Island cemetery, later moved to the Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland.

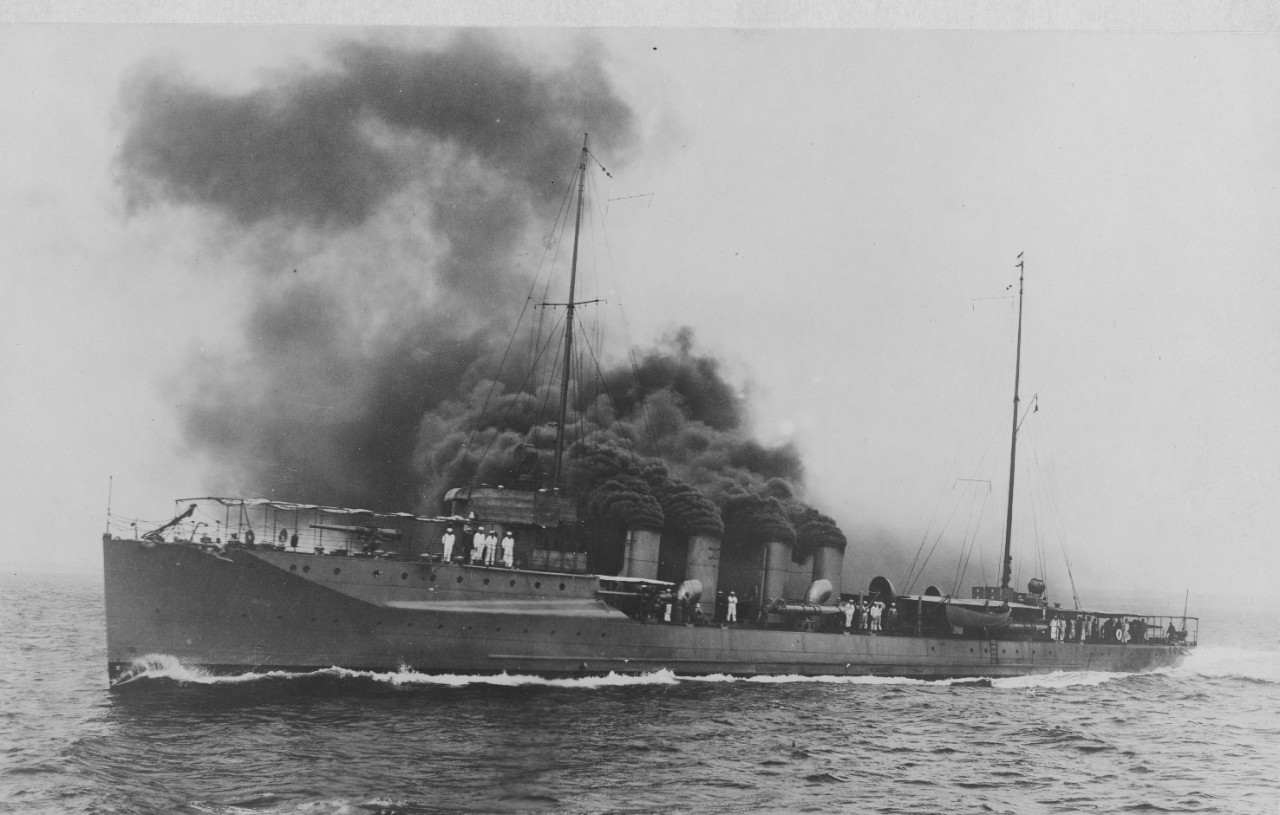

(Destroyer No. 54: displacement 1,020 (standard); length 305'3", beam 30'6"; draft 9'3½"; speed 30.70 knots; complement 103; armament 4 4-inch guns, 8 21-inch torpedo tubes; class O’Brien)

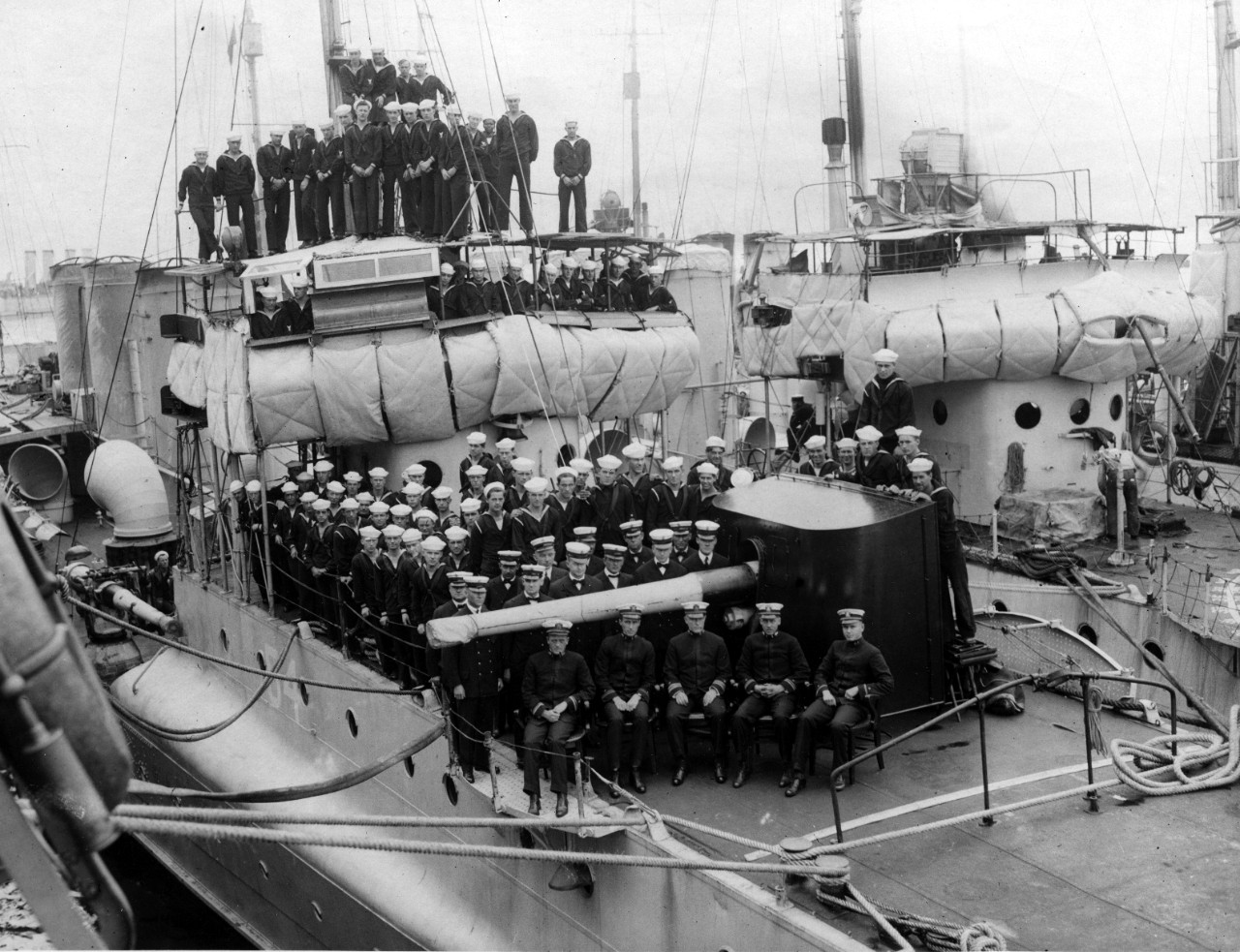

The first McDougal (Destroyer No. 54) was laid down on 29 July 1913 at Bath, Maine, by Bath Iron Works; launched on 22 April 1914; sponsored by Miss Marguerite S. LeBreton, granddaughter of Rear Adm. McDougal; and commissioned on 6 June 1914 at the Boston Navy Yard, Lt. John H. Hoover in command.

After commissioning, McDougal was assigned to the Seventh Division, Torpedo Flotilla, U.S. Atlantic Fleet where she flew the broad pennant of the senior officer of the division when Lt. Cmdr. Leigh C. Palmer relieved Lt. Hoover on 27 July 1914. In April 1916, she was reassigned to the Sixth Division of the Torpedo Flotilla. In June 1916, the Torpedo Flotilla was renamed the Destroyer Force under which McDougal’s Sixth Division was placed in the Third Flotilla.

McDougal damaged her starboard propeller on 23 July 1916, while departing from alongside the oil dock at Melville, R.I. A board of investigation decided that no one on board was responsible for the accident. Her unfortunate summer continued, however, when she sideswiped Oklahoma (Battleship No. 37) on 1 August 1916, although the damage was superficial.

Reports reached Newport, R.I., that U-53 (Kapitänleutnant Hans Rose, commanding) was sinking five foreign merchant vessels off the Massachusetts coast on 8 October 1916, McDougal stood from Newport to assist with the recovery of survivors, putting to sea on such short notice that she left half of her crew ashore. The undermanned destroyer located the Dutch turret-hull steamer Blommersdijk as she was hove to close to the U-boat with the Germans warning her to abandon ship. The British steamship Stephano, bound for New York, also lay nearby. The two steamers transferred their crews and passengers to the neutral U.S. destroyers and McDougal received several crewmembers from the Dutch vessel. After the survivors were secured, the Americans watched as U-53 carefully sank the two merchant vessels with torpedoes. McDougal returned to port to disembark the survivors arriving early on 9 October. Soon thereafter, she departed Newport on a reconnaissance mission to scout the coast of Maine from Bar Harbor to the Kennebec River (12-16 October).

On 25 March 1917, the Navy ordered the Atlantic Fleet to assemble in Chesapeake Bay where the fleet stationed itself in the York River to protect from potential U-boat attacks. Following the U.S. declaration of war (6 April 1917), Division Eight of the Destroyer Force, including McDougal, received orders to prepare for distant service. She sailed for New York under Lt. Cmdr. Arthur P. Fairfield, leaving the York River on 14 April in company with Wainwright (Destroyer No. 62), Conyngham (Destroyer No. 58), and Davis (Destroyer No. 65). The squadron was joined by Wadsworth (Destroyer No. 60) and reached New York at 6:00 p.m. on the same date. The following day, the destroyers were ordered to fit out for distant service, steaming to Boston, arriving on 16 April where Porter (Destroyer No. 54) joined them. McDougal went into dry dock for repairs and alterations that were completed in time to join the division when it cleared Boston.

Designated the flagship of the six-ship Special Service Division (later designated Eighth Division), Wadsworth stood out of Boston, leading Porter, Davis, Conyngham, McDougal, and Wainwright on 24 April. One day out, Cmdr. Taussig opened his sealed orders directing him to proceed to Queenstown [Cobh], Ireland, and to report “to the Senior British Naval Officer present, and thereafter cooperate fully with the British Navy.” While en route on 3 May, destroyer HMS Mary Rose met the division and fell into formation, escorting it into Queenstown (Base Six) on 4 May. The arrival of the destroyers was popularly hailed as the “Return of the Mayflower” and the people of Queenstown and the ships then in the harbor accorded them a rousing welcome. Upon arrival all the destroyer commanding officers called on the American consul, Vice Adm. Sir Lewis Bayly, RN, Commander of the Naval Forces on the Coast of Ireland, and the brigadier general commanding the British Army forces at Queenstown.

Early patrols produced a number of alleged submarine sightings. On 15 May 1917, McDougal was on patrol when she sighted a conning tower of a submarine 8,000 yards away. She closed on the enemy but the vessel submerged after the U.S. destroyer progressed 1,000 yards. An eagle-eyed crew member then spotted a sub at 11,000 yards which submerged long before the destroyer could reach her position. Before nightfall the alert vessel sighted a periscope at 200 yards which immediately retracted below the surface. On 19 May, while escorting the British steamship Cassandra, Mac opened fire on two supposed periscopes that turned out to be floating spars.

At 8:45 p.m on 5 June 1917, McDougal was steaming on the starboard bow of a convoy when a torpedo from U-66 (Kapitänleutnant Thorwald von Bothmer) struck the British steamer Manchester Miller on her port side. The escort swung around the stricken merchantman searching unsuccessfully for the origin of the torpedo. The torpedo’s explosion killed second engineer and seven men in the engine room but McDougal rescued the other 32 members of the crew. The British sloop HMS Camellia responded to the reports of the torpedoing and attempted to tow the listing steamer to port, but soon realized the ship was lost. Manchester Miller sank bow first at 9:34 p.m.

A little over a month later, McDougal joined Benham (Destroyer No. 49) in escorting merchant ships and engaged in anti-submarine maneuvers at 4:04 a.m. on 13 July 1917. McDougal guarded the British steamer Pentwyn while her escort continued to hunt the alleged submarine. As Benham continued the search, McDougal relieved her of escort duty and handed the convoy over to the next scheduled escort, British sloop HMS Primrose. Exactly two weeks later, the U.S. destroyer picked up 24 survivors from the Spanish steamship Begona No.4 which had been sunk by the gunfire of U-35 (Kapitänleutnant Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière) an hour earlier, transferring them to a tug on 31 July.

On 20 August 1917, McDougal was drydocked at Royal Dockyard in Chatham, England. There, she remained, refitting, until 1 September 1917, when cleared Chatham and set course to return to Queenstown.

While McDougal was escorting a mercantile convoy on 8 September 1917, an alert lookout spotted a submarine on the starboard bow at 1:21 a.m. McDougal charged through the darkness and closed to within 500 yards of the vessel before her target submerged. She dropped two depth charges after reaching the spot where her adversary had gone under. The destroyer circled and noticed an oil slick but darkness precluded any further investigation. As McDougal dropped her depth charges she noticed another convoy ahead of the submarines former position only half a mile away. At 11:00 a.m., she conducted a more thorough investigation of the site and noticed an oil slick one mile in diameter but no wreckage to indicate the destruction of a submarine. Vice Adm. Bayly later commended the crew and concluded that if McDougal had not intervened the convoy would have likely suffered serious damage. The Navy later mentioned the action in the Navy Cross citation for Cmdr. Fairfield.

On 19 October 1917, McDougal was escorting a convoy (H.D. 7) led by the British armed merchant cruiser Orama. At 5:51 p.m., escort leader Conyngham was exchanging signals with the Orama attempting to convince the convoy commodore to change course due to reports of enemy submarines ahead. While engaged in the exchange, Orama was struck by a torpedo fired by U-62 (Kapitänleutnant Ernst Hashegan) fired from within the confines of the convoy. McDougal joined Conyngham in hunting for U-62 at full speed until the latter dropped a depth charge, bringing oil and debris to the surface.

As other destroyers saved the crew of the sinking Orama, McDougal believed she sighted another submarine wake and dropped a depth charge. The violent explosion of the underwater ordnance, however, convinced some on the nearby British merchant vessel Clan Lindsay that she was torpedoed and one boat full of panicky crewmembers abandoned ship. McDougal located and towed the lifeboat, with its temporarily subdued occupants, safely back to the merchantman, but as the lifeboat’s people continued to resist the boat was accidently smashed between the destroyer and the British freighter. No one on board was harmed in the initial crash, which only damaged the lifeboat, but two panic-stricken individuals jumped overboard and were not recovered. McDougal helped recover the remainder of the boat’s occupants without further incident.

Lt. Cmdr. William T. Conn relieved Cmdr. Arthur P. Fairfield on 3 December 1917, and before the month was out, on 22 December, McDougal was at sea escorting the troop transport Leviathan (Id. No. 1326). Zig-zagging at 20.5 knots to keep up with the fast liner proved too much for the destroyer in the heavy seas through which the convoy was traveling. Two swells washed over McDougal’s deck in immediate succession, inflicting damage on the destroyer.

Soon thereafter, three days after Christmas, 28 December 1917, McDougal was dispatched from Queenstown to convoy the torpedoed American “Q-Ship” Santee back to Queenstown. At 7:10 a.m. she was detached from escort duty and ordered to begin a patrol. Three hours later, she spotted a torpedo approaching three points on the port bow. The attack failed and McDougal changed course closing on the source of the torpedo. After reaching the alleged source the crew could not find any indication of a submarine. Later, the commanding officer admitted that the torpedo sighting was probably mistaken. The following day, McDougal was on patrol when she spotted an oil slick, 16 miles long, and dropped two depth charges after locating bubbles at what appeared to be the perceived source, but did not observe any results.

On 16 January 1918, McDougal entered dry dock at the Cammell-Laird yard, Liverpool, England, where workmen carried out repairs and alterations. Among the additions were racks that allowed the vessel to carry more depth charges, and two Thorneycroft depth charge projectors that allowed the destroyer to fire depth charges to port and starboard. Work was completed on 27 January.

While steaming in the Irish Sea on escort duty at 3:55 a.m., shortly before the end of the mid watch on 4 February 1918, lookouts in McDougal sighted two white lights on her port beam and port bow. Unknown to McDougal, convoy H.G. 49 had steamed into a collision with the U.S. escort’s convoy. Due to the low visibility, McDougal slipped into a precarious location between two columns of the encroaching convoy, and turned on her running lights to advertise her position to the two vessels but spotted a third light ahead on the starboard bow. The officer-of-the-deck maneuvered McDougal to avoid that vessel but immediately ordered right full rudder and full speed ahead to avoid a large steamer then sighted 300 yards away closing on McDougal’s port bow. Soon, however, the destroyer was forced to go full astern to avoid the vessel on the starboard bow and was rammed on the port side by the large British steamer Glenmorag. The collision cut off a portion of the destroyer’s stern, and a sailor who had been asleep in the aft compartment claimed that the hull of the steamer left a scuff mark on his jacket. The ship providentially avoided tragedy, however, and the crew suffered no casualties. Reeling but not deterred, McDougal’s complement sprang into action and kept the vessel afloat. Paulding (Destroyer No. 22) stood guard as the crippled destroyer lay dead in the water until British armed yacht Beryl attached a line and towed her to Liverpool. She arrived on 6 February and put into the Cammell-Laird wet basin. A subsequent board of investigation found no fault on the part of McDougal.

While waiting transfer to dry dock on 11 February 1918 at Liverpool, an officer from the British armored cruiser HMS Shannon visited the damaged destroyer, and explained that the crews of Russian patrol boats in the port, Rasveet and Probiet, had mutinied in support of the Bolshevik revolution and threatened to kill their officers. The British officer, leading a boarding party to capture the mutineers, initially requested rifle ammunition, but after realizing the U.S. ammunition would not fit his crew’s weapons, he instead requested an American machine gun crew from McDougal participate in a joint boarding action. Consequently, a seven man machine gun crew armed with a Benet-Mercier joined 25 Royal Marines with fixed bayonets boarding Rasveet. The boarding party arrested 50 of the crew without a fight. The combined British-American force next boarded the Probiet and similarly arrested the crew. The actions caused no casualties on either side, and neither the British-American force nor the Russian crews fired their weapons. McDougal transferred to the dry dock for repairs on 16 February 1918.

On 26 March 1918, Cmdr. Conn was relieved by Lt. Cmdr. Vaughn K. Coman. While under repairs, workers fitted McDougal with a “K-Tube,” a primitive anti-submarine listening device that purported to allow destroyer crews to hear and locate submarines underwater. The ship still lay drydocked when the workers of the Cammell-Laird shipyard struck on 27 May, performing no work until 30 May.

McDougal completed repairs on 20 July 1918, and soon thereafter steamed to Brest, France, for convoy duties. She steamed for Brest on 23 July after a stop at Queenstown. While on the solitary cruise from Queenstown to Brest on the same date, lookouts spotted a dark slate-colored object six miles away. McDougal went full ahead and closed at 29 knots, but what they had sighted disappeared two minutes later. The destroyer dropped two depth charges on a slight oil slick, but was unable to determine where the submarine submerged and retired after a short search of the vicinity.

McDougal received an S.O.S. from the cargo ship Westward Ho (Id. No. 3098) on 8 August 1918, after the Naval Overseas Transportation Service ship had been torpedoed by U-62 (Kapitänleutnant Hashegan). At 12:55 p.m., lookouts spotted a periscope on the starboard bow that soon dipped beneath the waves. The destroyer closed on the spot of the sighting and dropped a barrage of ten depth charges. Roe (Destroyer No. 24) and Fanning (Destroyer No. 37) joined the hunt and dropped patterns of their own. There was no indication of success and McDougal embarked survivors who were later returned to the cargo ship when she stayed afloat. Three days later, while still guarding the damaged vessel, Connor (Destroyer No. 72) sighted a submarine and both she and McDougal closed on the sighting. The latter was forced to break off her approach, however, when a pattern of depth charges thrown from Connor exploded 200 yards from her causing slight damage. The destroyers did not locate any indication of a submarine in the area.

On 19 October 1918, McDougal sighted a periscope two points on her starboard bow 400 yards ahead. The ship rang up full speed and closed on the target, dropping a pattern of seventeen depth charges after the periscope slipped under the surface. Lt. Cmdr. Coman believed that one charge fired starboard from the Thorneycroft depth charge thrower landed close to the submarine. McDougal searched the area for two hours utilizing the ship’s “K-tube” to no effect.

That proved to be McDougal’s last reported engagement before the Armistice ended the World War on 11 November 1918. Following the Armistice, she served as part of the escort for troop transport George Washington (Id. No. 3018) when the transport arrived at Brest on 13 December with President Woodrow Wilson on board.

On 22 December 1918, McDougal left with 11 other American destroyers for the United States. After touching the Azores and Bermuda, the vessel returned to the New York Navy Yard on 3 January 1919. There, she refitted and received repairs in dry dock. She then assisted in the transatlantic flight of Lt. Cmdr. Albert C. Read’s crew in flying boat NC-4 in May 1919.

Steamship William O’Brien reported that she was in distress 18 April 1920. After the ship likely foundered, McDougal took part in the search for survivors that was called off on 26 April. On 1 July 1920, McDougal was re-designated as DD-54. In May 1921, she took part in depth charge experiments, and on 26 May 1922 she was put out of commission at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

The passage of the 18th Amendment, Prohibition, had spawned a thriving traffic in smuggling alcoholic beverages by 1924. The Coast Guard’s small fleet, charged with stopping the illegal maritime importation of liquor, was unequal to the task. Consequently, President Calvin Coolidge proposed to increase that fleet with the Navy’s inactive destroyers, and Congress authorized the necessary funds on 2 April 1924. McDougal transferred from the Navy Department to the Treasury Department at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 7 June.

Coast Guardsmen and Navy yard workers went to work and overhauled McDougal’s hull and stripped her of depth charge gear and torpedo tubes. Adapting the vessel for law enforcement service was thought to be less costly than building new ships, but in the end, the rehabilitation of the destroyer became a saga in itself because of the exceedingly poor condition of the war-weary ship. Regarding the rehabilitation of the destroyers for active service, historian Malcolm F. Willoughby noted, “The winter of 1924-25 was exceptionally severe. Work on destroyers went on day after day in close to zero weather often without the vestige of heat. Some boilers and engines were in fairly good condition, while others were in a deplorable state. It took nearly a year to rehabilitate these vessels in order to bring them up to seaworthiness and operational capability. Additionally, the destroyers were by far the largest and most sophisticated vessels ever operated by the Coast Guard; trained crewmen were nearly non-existent. As a result, Congress subsequently authorized hundreds of new enlisted billets. It was these inexperienced recruits that generally made up the destroyer crews.”

As part of her preparation for operational deployment, McDougal received orders to calibrate her radio compass on 22 February 1925. Initially, intended to be stationed at Cape May, N.J., McDougal received orders on 2 April to be homeported at New York, subject to the Commander, Destroyer Force based on board the Coast Guard cutter Redwing at New London, Conn. Maintaining her name, but having been re-designated CG-6, she was commissioned into the Coast Guard on 13 May 1925 at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Lt. Cmdr. Stanley V. Parker, USCG, in command.

While capable of well over 25 knots, seemingly an advantage in the interdicting of rum runners, McDougal and her fellow destroyers were generally easily outmaneuvered by smaller vessels. As a result, the destroyer picketed the larger supply ships (“mother ships”) on Rum Row in order to prevent them from off-loading their illicit cargo onto the speedier contact boats that ran the liquor into shore to be transferred to waiting trucks.

Within a year of entering operational service with the Coast Guard, McDougal was on the drilling ground conducting gunnery exercises for the Gunnery Year 1925-1926. In the only year in which the destroyers and cutters competed directly, McDougal stood ninth among the 22 ships which fired the short-range battle. McDougal fired 17 shots with 4 hits. After her gunnery training, McDougal departed New York on 21 March 1926 bound for service with the Norfolk (Va.) Division. Having made her way to the Virginia capes, she was detached from her temporary service on 3 April, and made her way back to her regular patrolling area based from New York.

The destroyer seized the vessel Rook ten miles off Montauk Point, N.Y. on 22 June 1926, and two days later, she seized the British-flagged schooner Rosie M.B., out of Halifax, N.S. This second seizure was made between Montauk Point and Block Island, R.I. The vessel was within the 12-mile limit of U.S. territorial waters and was carrying 83 cases of Scotch malt whisky. The schooner was taken under tow, brought into New York, and turned over to U.S. Customs officials for adjudication.

During Gunnery Year 1926-1927, McDougal and the other destroyers conducted both short-range and long-range battle practices. She stood first after the short-range practice, but only managed to rate ninth in the long-range. In the end, she finished 6th among the 16 destroyers in the competition. Later, from 25-28 June 1927, McDougal’s crew conducted small arms training and then returned to the New York Navy Yard on the morning of the 29th. Only 12 members of the 60-man crew qualified as marksman, sharpshooter, or expert. After her time on the range, McDougal and her crew returned to her regular duties patrolling the waters along the Eastern seaboard.

The target shoots for Gunnery Year 1928-1929 were based from three Southern locales, Charleston, S.C., Brunswick, Ga., and Fernandina, Fla. McDougal departed New York for target practice at Charleston, S.C. on 8 March 1929. The destroyer arrived on the training grounds on the 11th. Firing her short-range practice first, McDougal shot poorly, rating 20th among the 24 destroyers in the fleet. Her final position was raised to 10th overall after her 6th place standing in the long-range practice. McDougal stood out of Charleston bound for New York on 7 April; she arrived the next day. Upon her return to New York the destroyer continued her regular patrolling and interdiction operations.

McDougal entered the New York Navy Yard for maintenance during the winter of 1930. Those repairs were completed on 26 March and three days later, she got underway and returned to the Stapleton CG Station. After conducting additional maintenance subsequent to her yard period, she departed for target practice at Pensacola, Fla., on 6 April. After arriving on the drill grounds, the ship conducted her annual gunnery exercises and competed against her fellow destroyers. Her standing for the Gunnery Year 1929-1930 competition saw a considerable drop off from previous years. McDougal finished second to last among the 19 destroyers in the annual shoot. After the gunnery exercises at Pensacola, the destroyer remained in Southern waters through the spring. On 4 May, she left St. Petersburg, Fla. bound for Charleston, from whence she operated into late June. After several months away, McDougal stood out of Charleston on 26 June for a return to her home station at Stapleton. The destroyer made two seizures in the latter months of 1930. First, she seized the Canadian oil screw Rex II of Digby, N.S., on 22 October 1930 for running without her lights at night trying to avoid surveillance and for suspicion of engaging in the smuggling trade. Later, she seized the Canadian oil screw, Isabel H of Yarmouth, N.S., for like violations.

Continuing her routine interdiction patrols into 1931, McDougal departed Stapleton on 17 April for target practice at St. Petersburg and arrived at Egmont Key, Fla., on 22 April. The ship’s performance under Ens. Marius DeMartino, her gunnery officer, was a marked improvement from the preceding gunnery year. Finishing fourth in both battle practices saw the ship rate fifth among the 13 destroyers. Having contributed to Division Two’s top standing among the three destroyer divisions, McDougal departed St. Petersburg on 21 May and stood into Stapleton three days later. While on patrol in the fall, McDougal seized the speedboat Greyhound with contraband fifteen miles from the Shinnecock (N.Y.) Light on 16 October. Arresting four prisoners, the destroyer was directed to deliver them to Customs officials at New York City.

Shortly after New Year’s Day, on 16 January 1932, McDougal got underway from Stapleton bound for Norfolk. The ship finally arrived at St. Petersburg for the Gunnery Year 1931-1932 exercises on 20 February. The ship’s standing remained fairly consistent with that of the previous year as the ship stood fourth overall. With the completion of the gunnery training, McDougal left St. Petersburg on 22 March and moored at Stapleton on the 25th. After returning from Florida, McDougal was damaged while moored at Pier 17, Stapleton CG Station, on 3 May 1932. The subsequent investigation saw the commanding officer and executive officer receive letters of admonition for their respective roles in the incident. Despite the damage, the ship carried on her patrolling operations through the end of the year.

Still based from Stapleton on 1 January 1933, McDougal departed the CG Station on 16 January for the Gunnery year 1932-1933 target practices which were again conducted at St. Petersburg. Arriving on 20 January, McDougal was among only six destroyers that competed in the annual shoot, Shaw (CG-22), Porter (CG-7), and the flush-deckers, Abel P. Upshur (CG-15), Hunt (CG-18), and Semmes (CG-20) being the others. In this small group, McDougal placed fourth overall with a fifth place in the short-range practice and a third place in the long-range. With her gunnery training concluded, she left St Petersburg for Stapleton on 22 February and arrived at her home station on 24 February.

McDougal was anchored off Sandy Hook, N.J., on 4 April 1933, when she intercepted a radio message concerning the Navy airship Akron (ZRS-4). She received further orders to get underway and proceed at “all possible speed” to a position 20 miles from Barnegat Light, N.J., to assist the downed airship with Rear Adm. William A. Moffett embarked. At 0700, the heavy cruiser Portland (CA-33) took charge of search operations. McDougal operated under her direction through the remainder of the day, but at 1821, she received permission to proceed to port to replenish fuel and supplies. She later moored at Stapleton at 1152. She returned to the search on 6 April and continued until ordered to return to port, which she did at 2037 on 8 April.

McDougal’s grueling anti-smuggling interdiction duties eventually wore on her and over time she, along with her fellow former Navy destroyers, had become unfit. McDougal arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 26 May 1933 and the Coast Guard decommissioned her, along with Tucker (CG-23), Porter, Davis (CG-21), Shaw (CG-22), Cassin (CG-1), and Conyngham (CG-2), on 5 June. Turned over to the responsibility of the Coast Guard representative at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, the destroyer was returned to the Navy Department on 30 June.

The Navy stripped the vessel of her name for use on a new destroyer, leaving her to be known only by her identification number, DD-54. On 5 July 1934, DD-54 was stricken from the Navy Register and sold for scrap.

S. Matthew Cheser and Christopher B. Havern, Jr.

3 May 2017