Kearsarge II (Battleship No. 5)

1896–1955

The second U.S. Navy ship named for the mountain that rises in the White Mountains in Merrimack County, N.H.

(Battleship No. 5: displacement 11,540; length 375'4"; beam 72'3"; draft 23'6"; speed 16 knots; complement 553; armament 4 13-inch; 4 8-inch, 14 5-inch, 20 6-pounders, 4 1-pounder automatic guns, 4 1-pounder rapid-fire guns, 4 M1895 Colt-Browning machine guns, 2 3-inch rapid-fire field guns [landing force], 4 18-inch torpedo tubes; class Kearsarge)

“Of the old wooden vessels of the Navy which were in active service at the date of my last report,” Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert observed in his annual report for the year 1894, “one, the Kearsarge, was wrecked in February last, and her name has since been regretfully stricken from the Navy list…There is still a feeling, deep-seated, widespread, and fully shared by the Navy Department, that Kearsarge is a name that ought not to be permitted to die out of the Navy list. I respectfully suggest that you recommend Congress to authorize the construction of a battle ship to perpetuate this name. The Department, it is true, approves the policy heretofore adopted of naming our battle ships for States—the pillars of the Union; but the propriety of making an exception to this rule in favor of the Kearsarge would, I believe, be universally recognized.”

Congress authorized the construction of the two ships of the class, Kearsarge and Kentucky (Battleship No. 6), on 2 March 1895. On 2 January 1896, the Navy signed the contract for the second Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5), which was laid down on 30 June 1896 at Newport News, Va. by the Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co.

Kearsarge was sponsored by Mrs. Herbert Winslow, wife of Lt. Cmdr. Herbert Winslow and daughter-in-law of Adm. John A. Winslow, who -- then captain -- had commanded the first Kearsarge, a sloop-of-war, when she sank Confederate raider Alabama on 19 June 1864. Kearsarge was launched on 24 March 1898, alongside Kentucky during a surge of patriotism following the sinking of second-class armored battleship Maine in Havana, Cuba, on 15 February 1898. An estimated 20,000 people converged on Newport News for the launching, taxing the area’s accommodations and communications. The Chesapeake & Ohio Railway ran several excursion trains to help alleviate the crush, and chartered Chesapeake Bay steamers carried additional people from Baltimore, Md., and Washington, D.C. Crewmen on board Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3) and monitor Puritan viewed the ceremony from the ships when they anchored nearby, and people packed the shipyard piers and spilled over onto the river bluffs and watched as the two battleships slid down the ways, Kearsarge first, followed by her sister. Kearsarge was commissioned on 20 February 1900, Capt. William M. Folger in command.

Kearsarge became flagship of the North Atlantic Squadron on 1 June 1900, and sailed along the Atlantic seaboard and in the Caribbean, and then (3 May–3 June 1902) completed an overhaul in dry dock at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y. Following the yard work, Kearsarge rejoined the squadron for a series of training cruises in New England waters. The ship lay to in Gardiner’s Bay, L.I. (16–17 July 1902), and operated off Menemsha Bight off Martha’s Vineyard, Mass. (17–18 and 24–25 July, 29 July–1 August, 8–9, 11–13, and 24–31 August), Woods Hole, Mass. (26–29 July, 4–7 and 13–15 August), New London, Conn. (1–4 and 9–11 August), Great Point, Mass. (15–16 August), Rockport, Mass. (16–20 and 24 August), Cape Ann, Mass. (20–24 August), Block Island, Mass. (1–2 [lay to overnight off Cerberus Shoal], 3–4, and [via Newport, R.I.] 6–7 September), and Rocky Point, L.I. (4–5 September). The ship completed her voyage and stood in to Tompkinsville [Staten Island] on the 8th, and then (8 September–7 November) underwent repairs at the New York Navy Yard.

The flagship coaled and provisioned at Old Point, Va. (10–15 November), and then (20–21 November) turned her prow toward warmer southern climes and visited San Juan, P.R. Kearsarge followed that port call by taking part in a fleet search problem, primarily in the waters off Culebra Island, P.R. (21 November–4 December), lay to off Mayagüez Island, P.R. (9–10 December) and finished the problem off Culebra (10–19 December). The ship rounded out the year by spending Christmas at Port of Spain, Trinidad (21–27 December) and Port Castries, St. Lucia (28–29 December), before resuming training off Culebra (30 December 1902–1 February 1903). Kearsarge stood in to Basseterre, St. Kitts (2–5 February 1903) and Ponce, P.R. (6–11 February), and then departed those tropical waters and visited Galveston, Texas (18–26 February). The battleship carried out target practice off Pensacola, Fla. (28 February–3 April), and then (18–23 April) cruised in the squadron around the tip of Florida and back to the Southern Drill Grounds off the Virginia capes (28–30 April). Kearsarge required additional repairs after her sail and reached Tompkinsville (1–3 May), from which she then (3 May–3 June) crossed the busy harbor and completed work in dry dock at the New York Navy Yard.

Rear Adm. Albert S. Barker meanwhile received orders to proceed to Washington, D.C., and report to the President of the General Board on 25 April 1903. Three days later he boarded armed yacht Mayflower and steamed down the Potomac River and out to the Southern Drill Grounds, where on 29 April he inspected ships of the fleet including Alabama (Battleship No. 8), Illinois (Battleship No. 7), Iowa (Battleship No. 4), Kearsarge, Massachusetts (Battleship No. 2), battleship Texas, Olympia (Cruiser No. 6), transport Prairie, several destroyers, a supply steamer, a collier, and some smaller craft. Barker relieved Rear Adm. Francis J. Higginson as Commander-in-Chief, North Atlantic Fleet, and broke his flag in Kearsarge on 30 April. The admiral then attended the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration in New York, and upon returning to New York Navy Yard received orders to shift his flag to Mayflower while Kearsarge served briefly as Adm. Charles S. Cotton’s flagship as he took the European Squadron on a cruise to those waters (3 June–29 July).

The battleship passed Sandy Hook, N.J., at about 1:00 p.m. on the 3rd as she set out across the Atlantic, and visited Southampton, England (14–17 June 1903). Kearsarge then turned her prow further eastward and visited Nyborg, Denmark (19–23 June), and then (23–30 June) took part in a regatta week at Kiel, Germany. The German Kaiser, Wilhelm II, personally steered the imperial barge along Kearsarge’s starboard side and boarded the U.S. flagship on the 25th, attended by Capt. Ferdinand von Grumme-Douglas. Meanwhile, a second vessel brought additional members of the imperial entourage alongside the ship to port, including Adm. Alfred von Tirpitz, State Secretary of the Imperial Navy, Adm. Gustav von Senden-Bibran, who led the Marinekabinett, Philipp F. Alexander, Fürst zu Eulenburg und Hertefeld, Graf von Sandels, and Generalleutnant Hans von Plessen. Adm. Cotton, Capt. Joseph N. Hemphill, Kearsarge’s commanding officer, and their officers greeted their guests.

After exchanging formalities the Kaiser remarked to Hemphill: “Now, Captain, I want to see your ship.” The commanding officer thereupon led the imperial suite on a tour of the battleship, and at one point, the Kaiser paused and jokingly asked an older sailor of the ship’s company how long he had served. “Twenty-four years,” the man replied. “That is long enough to be an admiral,” the Emperor observed wryly. As the visitors prepared to depart, Cotton assembled the crew and ordered them to give three hearty cheers for the Kaiser.

“It was a very happy and kind inspiration on your part to send the squadron to Kiel for the week,” the Emperor cabled President Theodore Roosevelt, “and, thanks to this fact, I was able to inspect the magnificent flagship Kearsarge to-day, when I was able to compliment the Captain in the exceptionally good state of efficiency and neatness of the ship and the fine appearance of his gallant crew.”

The Germans reciprocated the Americans’ hospitality and hosted a dance on board armored cruiser Prinz Heinrich, beginning that afternoon at 4:00 p.m. Following the soirée later that evening the Kaiser gave a dinner to Cotton, the U.S. captains, U.S. Ambassador to Germany Charlemagne Tower Jr., and Lt. Cmdr. Templin M. Potts, the U.S. Naval Attaché, on board imperial yacht Hollenzollern. Additional German guests joined the festivities including Prince Henry of Prussia and Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow.

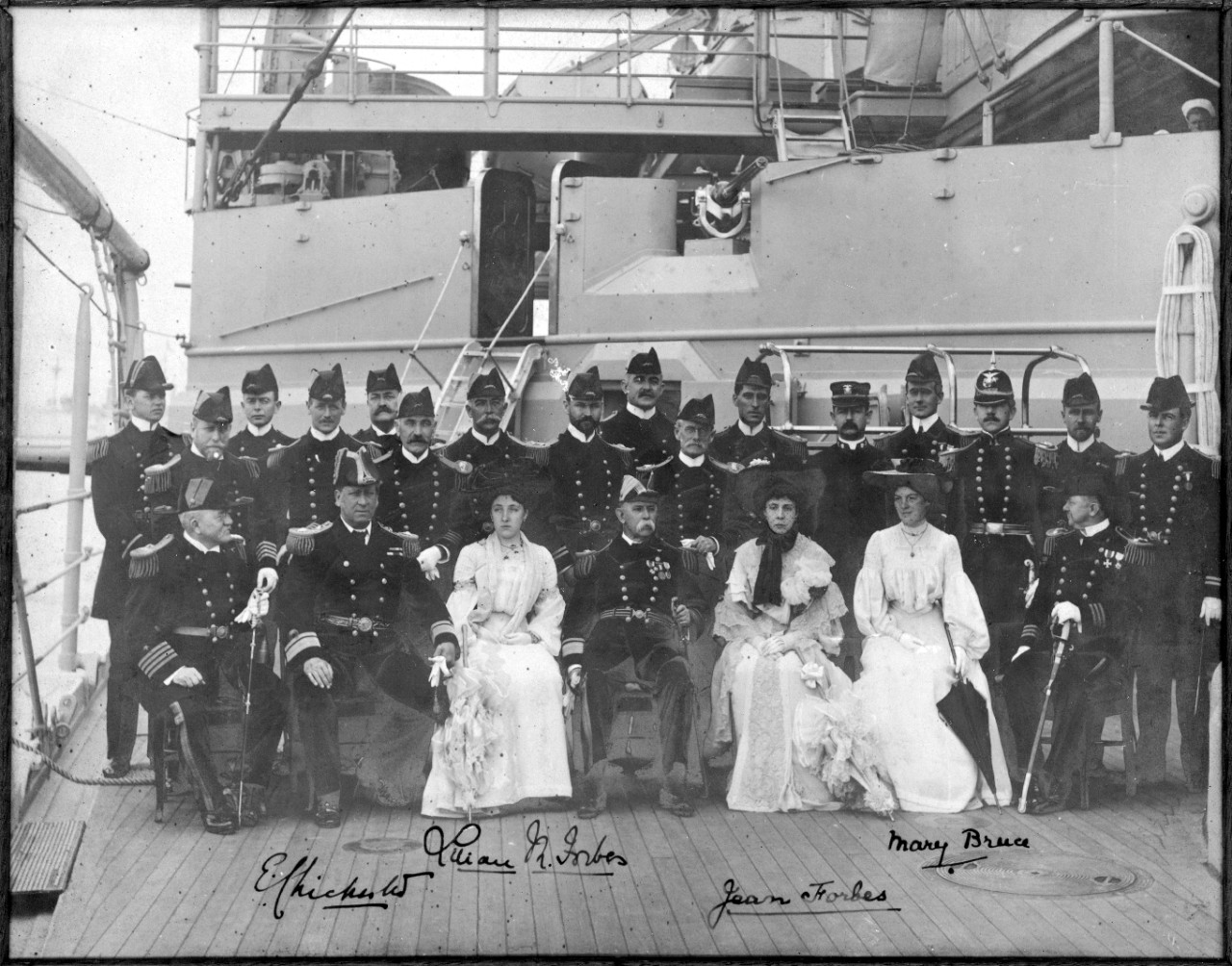

Kearsarge came about for Portsmouth, England, where the Prince of Wales -- who was subsequently crowned as King George V -- toured the battleship on 13 July 1903. Kearsarge and all of the vessels in the harbor, as well as those of the British Channel Fleet gathered off Spithead, dressed ship as royal yacht Victoria and Albert steamed through the armada. Kearsarge signaled the U.S. vessels and their bands, sounded drums and bugles in “four flourishes” in response to the flagship’s signal and fired a 21-gun salute, and Kearsarge hoisted the royal standard at the main as Victoria and Albert closed the flagship and the Prince of Wales boarded the American battlewagon. Cotton, Hemphill, and their officers greeted the Prince on the quarterdeck, and the party walked aft to inspect the ship’s marine guard, and then descended to the admiral’s cabin for breakfast.

The guests at the meal included Lord Selbourne, First Lord of the Admiralty, Adm. Lord Walter Kerr, RN, First Naval Lord, Field Marshal Lord Frederick S. Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, Vice Adm. Charles Beresford, RN, Commander-in-Chief, Channel Fleet, Adm. Sir Charles F. Hotham, RN, Commander-in-Chief, Portsmouth, Rear Adm. Reginald F.H. Henderson, RN, Admiral-superintendent, Portsmouth, Rear Adm. Sir Edward Chichester, RN, Capt. Sir Archibald B. Milne, RN, Flag Officer Commanding H.M. Yachts, and U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom Joseph H. Choate. Following their meal, the party toured the ship, and the Prince then departed amidst a further royal gun salute and took a train for London. Kearsarge returned to the U.S. at Bar Harbor, Maine (17–29 July 1903), and assumed duties as flagship of the North Atlantic Fleet.

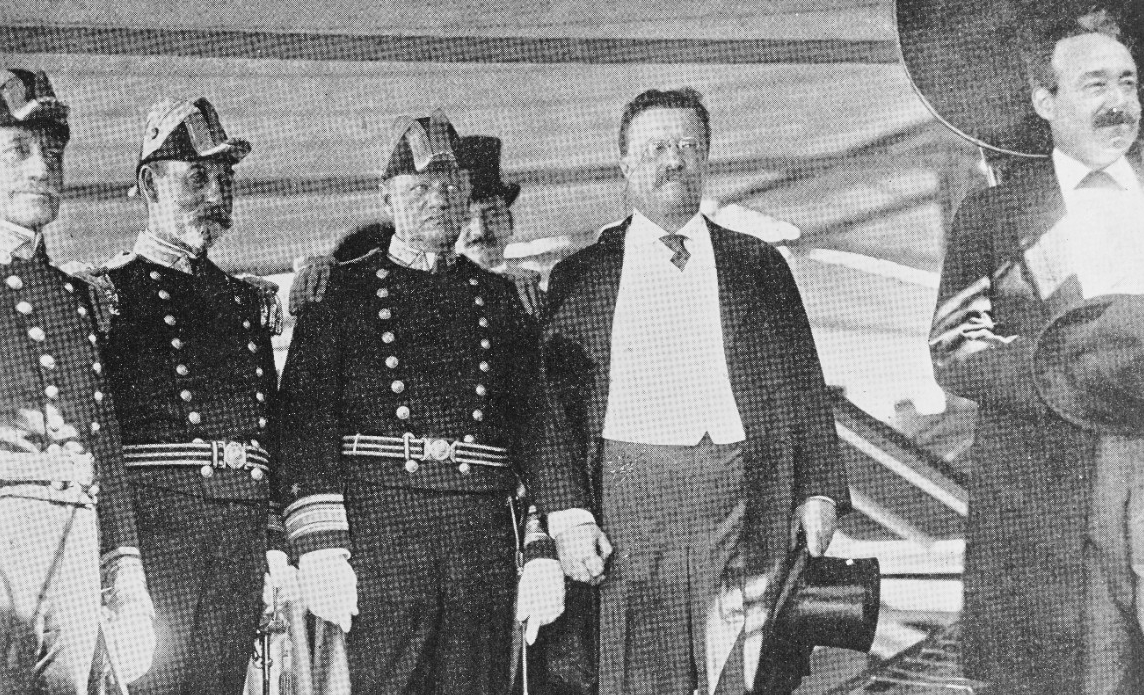

Rear Adm. Barker led the ships of the fleet in a series of “problems” [maneuvers] in New England waters following which many of them anchored in Smithtown Bay, L.I., on 14 and 15 August, and then (15–17 August 1903) took part in a Naval Review at Oyster Bay. The foreign naval attachés embarked on board Kearsarge, and Barker recalled the weather on 17 August as a “perfect day” as President and Mrs. Roosevelt and their daughter Alice, on board Mayflower, started on time and passed down between the columns of battleships and a division of destroyers. Each battlewagon in turn fired a 21-gun salute just before the presidential yacht passed, and their bluejackets manned their rails, bands played, and marine guards stood to attention. Mayflower came about following the review, and the flag officers and commanding officers of the participating ships and the foreign naval attachés then boarded the vessel and paid their respects to the chief executive. Kearsarge sailed from New York on 1 December for Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, where the United States formally took possession of that enclave on 10 December 1903.

President Roosevelt intended to project U.S. naval power into European waters, especially within the Mediterranean Sea, and directed the Navy to deploy several squadrons across the Atlantic during the winter of 1903 and 1904. The ships gathered and trained in the Caribbean, and on 9 May 1904 reached Guantánamo Bay and began coaling. The vessels mostly operated with fouled bottoms and required work in shipyards, but the Navy directed Barker to deploy the North Atlantic Battleship Squadron, consisting of Kearsarge -- again his flagship -- Alabama, Illinois, Iowa, Maine (Battleship No. 10), and Missouri (Battleship No. 11), across the Atlantic to Lisbon, Portugal. Illinois, Maine, and Missouri suffered accidents, however, that delayed their arrival, halving Barker’s strength.

Missouri’s steering gear broke down with the fleet carried out target practice on 11 March 1904, and Illinois and Missouri collided. Ill fortune hounded Missouri and while she conducted target practice on 13 April, an explosion in the port 12-inch gun in her after turret killed 36 men. Some of the survivors swiftly prevented the fire from spreading to her magazines and saved the ship, and three men received the Medal of Honor for braving the flames to extinguish the blaze — Chief Gunner Robert E. Cox, GMC Mons Monssen, and GM1c Charles S. Schepke. Missouri completed repairs at Newport News. The Navy continued to experience catastrophic problems with powder charges (see 13 April 1906).

Moroccan Sharif Mulai A. er Raisuni, known as “The Raisuli” to most Americans, kidnapped a man and a boy he erroneously believed to be U.S. citizens, Ion H. Perdicaris and Cromwell O. Varley, from Perdicaris’ villa in Tangier, Morocco, on 18 May 1904. The British, French, Germans, and Spanish all vied for control of Morocco, alternatively presenting extravagant gifts to Sultan Abdelaziz, in the hope of gaining coaling concessions for their ships. Raisuni resented the foreigners’ influence and apparently sought to embarrass the sultan, demanding a ransom for the safe return on his hostages. “Situation serious,” U.S. Consul Gen. Samuel R. Gummeré telegraphed to the State Department the following day, “Request man-of-war to enforce demands.”

The U.S. initially sent the South Atlantic Squadron, Rear Adm. French E. Chadwick in command, to Tangier to compel the release of the hostages. Chadwick wore his flag in Brooklyn and the squadron also consisted of Castine (Gunboat No. 6), Machias (Gunboat No. 5), and Marietta (Gunboat No. 15). Rear Adm. Theodore F. Jewell in the meantime relieved Cotton in command of the European Squadron, and received orders to reinforce Chadwick. Jewell directed the squadron to set course for Tangier, and Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland (Cruiser No. 19) reached that port on the first of the month, raising the number of U.S. warships there to seven.

Kearsarge led the other battleships of the squadron to Lisbon, where she entertained King and Queen Carlos I and Amélie and members of the court on 11 June. The presence of Barker’s battleships anchored in the Tagus roused Portuguese fears of U.S. expansionism, and the Navy instructed the admiral to lay to off Lisbon until 16 June, but extended his stay for two days. Their time at that port proved less arduous than feared as the admiral and his officers made the rounds of repeated soirees, Barker diplomatically observing that the queen so “charmed” him that he did not notice whether or not she wore jewels. The admiral added that he and his men “were pretty well tired out when all was over” before they set out for Gibraltar. Following a flurry of negotiations Raisuni received the ransom and returned Perdicaris and Varley on 21 June, and on 27 June the ships came about. The motion picture The Wind and the Lion, released in 1975, dramatized the incident.

The Navy originally planned to send the South Atlantic Squadron into the Mediterranean but instead dispatched the squadron down the west coast of Africa. The European Squadron spent Independence Day and some days afterward coaling and taking on stores at Gibraltar, where Illinois and Mayflower joined them, and Jewell then took them into the Mediterranean to Trieste in Austria-Hungary. Barker meanwhile deployed his ships into the Mediterranean, Missouri having been delayed by repairs after the collision with Illinois and following the squadron.

Beginning in September 1902, the U.S. Legation at Constantinople [Istanbul] had addressed a note to Ottoman Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II requesting that the Sublime Porte grant the same rights and privileges to American educational, charitable, and religious institutions that the Turks granted to a number of the European powers, basing the demand upon the favored-nation clause of the treaty between the U.S. and the Ottoman Empire. The sultan and his representatives repeatedly avoided the issue, however, and in April 1904, the U.S. Minister to Turkey, John G.A. Leishman, reported that the Turks finally refused the request on the grounds that “in regard to the schools and religious institutions, no difficulty being raised on their behalf, there is no reason for their confirmation.” Both governments alternatively postured, and in May Secretary Hay wrote to Leishman that “an imposing naval force will move in the direction of Turkey. You ought to be able to make some judicious use of this fleet in your negotiations within committing the Government to any action”.

The Americans selected Athens, Greece, as a strategic port that brought their ships within a day’s passage of the Dardanelles or Smyrna [Izmir] without making their actions too obvious — and avoiding insulting the sultan. Kearsarge, Alabama, Iowa, and Maine consequently anchored in Phaleron Bay at Piraeus, near Athens (30 June–6 July 1904). Missouri joined them on 3 July, and the American officers made the rounds of their Greek counterparts, and received King George I, Prince Andrew, and Princess Alice on board the flagship on the 4th of July. A number of European diplomats and journalists expressed their concern about the possibility of the crisis escalating. The Russians, in particular, considered the Turks to fall within their sphere of influence and their Ambassador to the U.S., Count Arthur P.N. Cassini, protested the battleships’ arrival. Barker nonetheless followed the visit by exercising the ships in the Aegean Sea, but their departure from port backfired when the sultan cancelled an audience with Leishman on 8 July. That day the battleships stopped briefly at Corfu in the Ionian Islands and the following day entered the Adriatic Sea, where they made port at Trieste (12–24 July). Baltimore, Cleveland, Olympia, and Mayflower joined them from Gibraltar. While there typhoid fever broke out among Kearsarge’s crew, which apparently began during her short-lived sojourn at Athens, and a number of men of the ship’s company convalesced at a hospital ashore.

The European Squadron rendezvoused with Illinois, which had steamed from Gibraltar, and thus reached Trieste a day behind Barker. The fleet then separated again, and the cruisers sailed to Corfu, while Barker signaled “Good Bye” to them and the battleships rounded the Istrian Peninsula and visited Fiume (25–30 July 1904). The absence of the fleet apparently emboldened the Turks and they twice more refused to grant Leishman an audience, both times scarcely hiding their disdain. The Americans grew exasperated, and on 16 July the State Department instructed Leishman to inform Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahmet Tevfik Pasha that it “failed to understand the delay in according him [Leishman] the treatment due to the friendly relations of the two countries”, and to demand an appointment at a fixed time and date. The acrimonious tone of these communiqués carried an implicit threat and on 29 July Leishman conferred with the sultan, who told him he would reply on the school question within four days. The State Department decided to play a strong hand, however, and informed the minister that Barker, who took his battleships through the Strait of Messina on 2 August and six days later back to Gibraltar, would be directed to hold his squadron “in readiness subject to orders.” Jewell brought his cruisers to Villefranche, France, where he received similar messages (3–7 August).

Roosevelt meanwhile on 5 August 1904 impatiently gathered the cabinet in a special session and ordered Jewell to deploy the European Squadron to Smyrna, and directed Barker to continue to maintain his battleships at Gibraltar. Leishman cabled Hay from Pera [Beyoğlu — a district in Constantinople] on 8 August, noting that the Turks had not replied or apologized, and recommending that “unless strong measures are adopted, matters may continue to drag along indefinitely.” Hay responded that Jewell and his ships steamed en route and would reach Smyrna “in a few days,” instructed him to obtain a satisfactory answer from the Turks before the fleet arrived, but added that if the Ottomans failed to “grant the moderate and reasonable requests of this Government”, then Leishman was to take an indefinite leave and depart on board one of Barker’s ships. These types of actions typically presaged fighting, and tensions correspondingly rose, and Leishman pointedly observed that the Turks preferred to negotiate the issue without confronting the fleet. When Hay returned from a meeting with Roosevelt that day, he found Turkish Minister to the United States, Chekib Bey, filled with “great perturbation about the fleet.” Hay attempted to calm Bey but added that the crisis arose largely because of Turkish intransigence. Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland visited Smyrna (12–15 August) and the Turks finally capitulated to the Americans’ demands. Barker then came about for U.S. waters, refueling and victualing at Horta at Fayal in the Azores (18–20 August) and returning to Menemsha Bight on 29 August. Jewell subsequently followed, concluding the momentous naval deployment to European waters.

Kearsarge and Alabama trained off Newport on 1 September 1904 and into the next day fired at targets off Menemsha Bight and Nomans Land, a tiny island located several miles to the southwest of Martha’s Vineyard. Kearsarge worked in the area until the 17th, and then waited at Tompkinsville until the 22nd, when a berth became vacant at New York Navy Yard so that she could complete an overhaul (22 September–28 December). The battleship repeated her winter sojourn southward and greeted the New Year at Hampton Roads, Va. (29 December 1904–9 January 1905), before she charted southerly courses to the Caribbean. Kearsarge trained off Culebra (14 January–17 February 1905) and then (19 February–22 March) off Guantánamo Bay. The experienced ship lay to at Pensacola (27 March–1 April), and on 31 March Maine relieved Kearsarge as the squadron flagship. Kearsarge fired at targets on the range at Pensacola (1–8 April), and following her gunnery practice rejoined her cohorts and steamed in the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida, and up the east coast to Virginian waters (8 April–2 May). The ship coaled at Old Point (7–8 May), and into the summer (15–19 and 23–26 May and 31 May–2 June) participated in exercises off the Southern Drill Grounds, breaking her times at battle stations by returning to Old Point.

The march of time caught up with Barker and he neared his retirement age, so Rear Adm. Robley D. Evans relieved Barker while the band played “Auld Lang Syne” during a ceremony on board Kearsarge on 31 May 1905. “The hauling down” of the admiral’s flag, the Army and Navy Journal observed, “was the occasion for a display of the esteem and appreciation in which he is held by the officers and men of late under his command.” Kearsarge continued to operate with the fleet and shaped a course for the Northern Drill Grounds off New York (6–8 June), after which she stood into that port on the North River, at times in company with her sister ship Kentucky (8–11 June). Kearsarge had her bottom cleaned and painted with two coats of Rahtgen’s paint while in Dry Dock No. 2 at the New York Navy Yard (11–21 June).

Kearsarge steamed with the squadron in New England waters that summer, and celebrated Independence Day at Provincetown, Mass. (1–12 July 1905). The work included standardizing her screws on the Measured Mile, a nearby range consisting of three towers that enabled navigators to cut fixes at the beginning, middle, and end points to determine their speed made good. The ship then (13–19 July) took part in a search problem with other ships off Newport, and returned briefly (22–26 July) to the waters of Hampton Roads for speed trials. Following that cruise she rejoined the squadron and set her bow northward again to New York (27 July–1 August), and after visiting that metropolis the squadron continued up the New England coast and visited Bar Harbor and Portland, Maine (3–11 and 11–15 August, respectively). The ships came about and made for Provincetown (15–17 August), and trained off Newport and Watch Hill, R.I. (19–25 and 25–28 August, respectively). Kearsarge returned to Provincetown (29 August–12 September), carried out preliminary gunnery practice off Target Range No. 3 nearby (12–29 September), and then (29–30 September) lay to off Provincetown. Following those exercises the battlewagon steamed to the Delaware River for some time (2–5 October) at League Island, Philadelphia. She came about for New York (7–12 October), and through the end of the month back to Hampton Roads, and visited the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md. (30 October–7 November). Kearsarge visited New York (8–20 November) and then (21 November–27 December) spent the holidays at Philadelphia, before wrapping-up the year with work at New York Navy Yard (28 December 1905–6 January 1906), where all of her 18-inch torpedo tubes were removed except for the forward starboard tubes. The ship steamed in company with Alabama, Illinois, and Maine, and then (8–17 January) took part in a wireless test with thye Dewey steel floating dry dock off Hampton Roads.

The battleship chartered southerly courses and trained with the First Division and Second Torpedo Flotilla off Culebra (22 January–6 February), and then (8–14 February) took part in a scouting problem off Port of Spain. Following those exercises the ship came about and trained off Guantánamo Bay, with brief visits to that harbor (19 February–31 March). Shen then set out for target practice on the target grounds in Cuban waters (1–13 April).

While Kearsarge shot at targets off Cape Cruz, Cuba, on the afternoon of 13 April 1906 -- exactly two years to the day after Missouri’s tragic fire -- a flash fire erupted in her forward port 13-inch gun turret. The gunners left the gun loaded at the end of a run over the target range, but a short circuit for supplying the current to the electric rammer heated the compartment. Molten metal ignited three sections of powder that they had lain on the deck and cooked-off the powder, killing two officers and eight men, and seriously injuring five others.

Swedish immigrant BMC Isidor Nordstrom was one of the first men to courageously enter the turret and helped bring out the wounded crewmen, actions for which he afterward received the Medal of Honor. Burning powder fell into the 13-inch handling compartment below the turret, and Seaman George Breeman, who manned a battle station in the adjacent powder magazine, quickly entered the compartment and stamped out the burning powder. He then returned to the magazine, closed the hatch to the handling room, and replaced the covers on the open powder tanks. For Breeman’s bravery and intrepidity he was awarded the Medal of Honor and, in addition, received a $100 gratuity. Escort ship Breeman (DE-104) was named in his honor and served from 1943–1948.

“The commander-in-chief,” Rear Adm. Evans cabled to the New York Herald from Caimanera, Cuba, on the 20th, “extends to the captain, officers, and men of the Kearsarge his sympathy at the loss of life and injuries sustained on board that ship. The circumstances immediately following the disaster, however, gave such an exhibition of discipline, self-sacrifice and heroic conduct that one must be proud of belonging to a service which furnishes such officers and such men.”

Kearsarge came about and completed temporary repairs at Guantánamo Bay (14–28 April 1906), briefly returning undauntedly to Cape Cruz on the 24th to complete her shooting. The ship returned northward with the squadron, and lay to off Tompkinsville (3–4 May) while awaiting her turn to proceed into the North River (4 May–1 June). Kearsarge standardized her screws off Provincetown (2–3 June), and accomplished some work in Dry Dock No. 2 at League Island [Philadelphia] (5–22 June). The ship required additional repairs, however, and entered Dry Dock No. 3 at New York Navy Yard (25 June–6 July). She returned to Norfolk through the 14th.

Kearsarge resumed her summer routine when she returned with the squadron to the northern operating areas. The ship trained off or visited a number of increasingly familiar ports: Rockport (16–30 July and 9–18 August 1906), Newport (31 July–7 August), North River (19–25 August), and Rockland and Camden, Maine (27–29 and 29–30 August, respectively). Kearsarge hove to off Smithtown Bay on Long Island Sound, N.Y. (1–2 September), while she prepared for a presidential review off Oyster Bay on the sound (2–4 September). Following the chief executive’s review, the ship turned northward and operated off Bar Harbor and Provincetown (6–23 and 24–27 September, respectively). The battleship then blasted away at targets on the range in Cape Cod Bay (27 September–14 October), but required repairs in dry dock at Norfolk Navy Yard and in New York Navy Yard (16 October–16 December and 17–29 December, respectively). Kearsarge rejoined the squadron at Hampton Roads in time for New Year’s Eve on 31 December 1906.

The ship charted southern courses to the Caribbean early in 1907 and took part in maneuvers and exercises, as well as gunnery practice, off Guantánamo Bay (7 January–10 February, 17 February–10 April 1907), broken by a transitory period off Mayagüez Island (12–15 February). Kearsarge returned to Hampton Roads and participated in a portion of the Jamestown Exposition, commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Jamestown Colony, held at Sewell’s Point, Hampton Roads (15 April–13 June). Her participation included a Presidential Naval Review off the roads (7–10 June), after which (14 June–8 August) she completed repairs in dry dock at League Island. Kearsarge steamed to New England waters and recorded her progress off Bradford, Jamestown, and Newport, R.I. (9–10, 10–11, and 11–12 August, respectively), and then (15–22 August) Provincetown. The ship came about and returned to Hampton Roads to prepare for a voyage that would carry her around the world. She worked-up on the Southern Drill Grounds (3–4 September), thrust northward to Rockport (8–13 September), and shot at targets in Cape Cod Bay (13 September–6 October), and then (8 October–5 December) completed some last minute repairs and upkeep at League Island.

Kearsarge sailed in the Second Squadron as one of the 16 battleships of the “Great White Fleet.” President Roosevelt dispatched the fleet on a global circumnavigation to serve as a deterrent to possible war in the Pacific; to raise U.S. prestige as a global naval power; and, most importantly, to impress upon Congress the need for a strong navy and a thriving merchant fleet to keep pace with the United States’ expanding international interests and far flung possessions. In addition, the President wanted to discover what condition the fleet would be in after such a transit, noting before the fleet sailed: “I want all failures, blunders and shortcomings to be made apparent in time of peace and not in time of war.” Rear Adm. Evans stated earlier that his ships put to sea “ready at the drop of a hat for a feast, a frolic or a fight.”

President Roosevelt reviewed the fleet as Kearsarge and 15 battleships steamed past presidential yacht Mayflower off Hampton Roads on 16 December 1907. The ships visited Port of Spain, Trinidad (23–29 December), crossed the equator on 6 January 1908, and anchored at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where a brawl between sailors from Louisiana (Battleship No. 19) and longshoremen marred the visit (12–22 January). Kearsarge battled heavy wind and navigated through dense fog while passing through the Strait of Magellan, and visited Possession Bay (31 January–1 February) and Punta Arenas, Chile (1–7 February), and Callao, Peru (20–29 February). The Great White Fleet then carried out gunnery practice at Magdalena Bay, Baja California, Mexico (12 March–11 April).

“Our ship held about 2,000 tons of the stuff,” a member of the ship’s company in Connecticut (Battleship No. 18) described coaling day. “All the deckhands would go down into the collier (coal supply ship) and fill these big bags with about 500 pounds. Then they'd hoist ‘em over to us down in the coal bunkers and we'd spread out the coal with shovels until all the bunkers -- about 20 -- were full to the top.”

Kearsarge steamed with her consorts along the west coast and visited Californian ports: Coronado (14–18 April 1908); San Pedro (18–19 April); Redondo Beach (19–25 April); Santa Barbara (25–30 April); Monterey (1–4 May); Santa Cruz (4–5 May); and San Francisco (6–18 May). Rear Adm. Charles M. Thomas relieved Evans while the fleet put into San Francisco, and Rear Adm. Charles S. Sperry subsequently relieved Thomas. Kearsarge meanwhile sailed in company with some of the ships and visited ports in Washington State: Port Townsend (21–23 May); Seattle (23–27 May); and Bremerton (27–28 May). Kearsarge returned to San Francisco on 31 May, and made the rounds of the bay area, stopping at San Francisco (1–2 July), Mare Island Navy Yard (2–4 July), California City Point (4–6 July), and back to San Francisco.

The Great White Fleet set out across the Pacific (7–16 July 1908). Kearsarge visited Honolulu in the Hawaiian Islands (16–22 July), Auckland, New Zealand (9–15 August), and three Australian ports: Sydney (20–27 August); Melbourne (29 August–5 September); and Albany (11–18 September). A cholera epidemic prevented crewmen from going ashore when Kearsarge and her consorts reached Manila, Philippines (2–10 October), but the sailors and marines received some consolation when their mail caught up with them.

The fleet made for Japanese waters but a typhoon slammed into the ships while they crossed the South China Sea. “The typhoon happened right off Formosa [Taiwan],” a sailor from one of the ships afterward recalled. “All you could see, when a ship was in trough, was the trunk of its mast above the wave tops. That was all you could see of an entire battleship. Then our turn would come to go into a trough, and we couldn't see anything for a while.”

Kearsarge visited Yokohama, Japan (18–25 October 1908). She joined seven of the other battleships and visited Amoy [Xiamen], China, following which, they returned to Philippine waters and visited Cavite and Manila Bay (7–8 and 12–14 November), and called briefly (8–12 November) at Olongapo on Subic Bay. Kearsarge and a number of the ships carried out target practice on the range in Manila Bay (14 November–1 December). The battleships finished shooting and rendezvoused with the rest of the fleet to continue the voyage across the Indian Ocean, and put into Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka], where tea merchant and yachtsman Sir Thomas J. Lipton hosted the men with complimentary tea (13–20 December).

The ships reached Suez, Egypt (3–4 January 1909), passed through the Suez Canal, and visited Port Said (5–6 January). They then divided into different groups to visit ports across the Mediterranean. Kearsarge cruised with the Fourth Division and reached Valetta, Malta (14–19 January) and Algiers (21–30 January), and then visited Gibraltar while the ships rendezvoused to reform the fleet (31 January–6 February).

The Great White Fleet crossed the Atlantic from Gibraltar and returned to the United States (6–22 February 1909), where President Roosevelt reviewed the ships at Hampton Roads (22–26 February). Kearsarge reached Philadelphia Navy Yard for voyage repairs on 7 March, where, on 31 March 1909, she was also placed in reserve. Shortly afterward (4 September 1909–17 June 1912) the battleship was decommissioned for modernization. The work gave the ship cage masts, new water-tube boilers, and another four 5-inch guns, and removed the 1-pounder guns and 16 of the 6-pounders. She was initially placed in commission with the second reserve following her yard work, but entered the first reserve with the Atlantic Reserve Fleet at Philadelphia on 30 September 1912. Kearsarge carried out a shakedown cruise (5–9 October), following which (10–15 October), she participated in a naval review in New York. On the following day Kearsarge passed the Delaware Breakwater and stood up the river to Philadelphia Navy Yard, where she was placed in ordinary on 31 May 1913.

Revolution tore Mexico apart as disparate groups lunged vengefully at each other and Gen. Victoriano Huerta, one of the strongmen, ruthlessly eliminated rivals and ambitiously amassed power among the Federales (government troops). The chaos endangered Americans caught in the midst of the war and President Woodrow Wilson called on U.S. warships to protect, and if necessary, evacuate them.

The seasoned battleship was re-commissioned on 23 June 1915, and during the summer operated along the Atlantic coast. She cruised with the naval militia on 2 July, and on 17 September stood out of Philadelphia in order to land a detachment of marines at Vera Cruz, Mexico. The ship embarked the marines at Pensacola on the 24th, and lay to off Vera Cruz (28 September 1915–5 January 1916). Kearsarge then carried marines of the Eighth Company to New Orleans, La., trained naval militia sailors from Massachusetts at Boston in January 1916, and on 4 February joined the Atlantic Reserve Fleet at Philadelphia. She then (1–12 August 1916) trained naval militia sailors from Massachusetts and Maine but otherwise remained mostly in port until the U.S. entered World War I on 6 April 1917.

That momentous day found Kearsarge at Boston Navy Yard where she assisted in seizing German ships Amerika, Cincinnati, Köln, and Wittekind of the Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft (Hamburg America Line), along with Deutsche Dampfschiffahrts-Gesellschaft Hansa (German Steamship Company Hansa) steamer Ockenfels. The German vessels had been interned in Boston, where Revenue Cutter Service-manned harbor tug Winnisimmet, which later became a Coast Guard vessel (WYT-84), faithfully watched the vessels during much of their stay. A number of the German crewmen went ashore during their internment, became Americans and found jobs, and some of their musicians put together a combined band and toured New England towns.

Boston Harbor Police steamer Guardian, manned by a captain, lieutenant, and three patrolmen, conveyed 123 federal officers of the Treasury Department at 3:30 a.m., and during the mid watch and morning watch they boarded and seized the German ships, which lay at East Boston, before they could escape. Guardian then made two return trips, carrying 273 German crewmen of the foregoing steamships to Long Wharf for internment, all under Kearsarge’s guns.

The prizes were transferred to the U.S. Shipping Board and all served under U.S. colors during the war: Amerika as the Navy’s transport Amerika and then America (Id. No. 3006), followed by Army transport America, and, in World War II as the Army’s Edmund B. Alexander; Cincinnati as Navy transport Covington (Id. No. 1409); Köln as Army transport Amphion and then Navy Amphion (Id. No. 1888); Wittekind as Army transport Iroquois and then Navy Freedom (Id. No. 3024); and Ockenfels as Navy cargo ship Pequot (Id. No. 2998). Some returned to civilian service following the war.

Two days later at 12:15 p.m., Guardian repeated her surprise attack and manned by her captain, a sergeant, and five patrolmen, augmented by a detail of ten men from that city’s Division 1, moored at Long Wharf, where the collector of the port and ten customs guards boarded. The busy vessel then crossed to Chelsea and her boarders seized Austro-Hungarian steamship Erny for the Treasury Department, and returned with four prisoners to Long Wharf.

Kearsarge began training thousands of armed guard crews and naval engineers in coastal waters ranging from Boston to Pensacola. The first of these men boarded the ship at Boston and she then (27 April–1 May 1917) set out for Base 2, the Navy’s designation for its expanding facilities at Yorktown, Va. Kearsarge spent most of the summer operating between Yorktown, Base 1 at Tangier Sound in Chesapeake Bay, and Base 3 at Hampton Roads. The ship accomplished some repairs at Norfolk Navy Yard (26–29 May and 12–13 July), but otherwise continued that training regimen and patrols through the summer and into the fall, when (13–14 and 20–21 June, 30 July–2 August, and 17–19 October) she also lay to off Base 4 at Wynne, Md., and off Base 5 at Solomon’s Island, Md. (24–25 May and 23–24 July). Additionally, the battleship steamed off Cape Charles, Va. (26–27 July), and then (19 August–1 October) turned her prow northward and operated from Base 10 at Port Jefferson, Long Island. Following those patrols, Kearsarge came about and resumed her training routine in Chesapeake Bay into the winter. The ship modified her schedule and lay to off Lynnhaven Roads, Va. (4–6 December), and also completed work at Norfolk Navy Yard into the New Year (15 December and 26 December 1917–1 January 1918). She then (9–23 January 1918) steamed to Boston Navy Yard, and returned to train in Chesapeake Bay into the spring, also touching at the mouth of the York River (15–16 March, 19 May, and 19–20 July). Kearsarge enjoyed a warmer visit to Boston that spring (15 April–8 May), and after participating in exercises in Chesapeake Bay shaped a southerly course, stopping at Charleston Navy Yard, S.C. (13–14 June), Key West and Pensacola, Fla. (17–18 June and 20 June–3 July, respectively), and during her return voyage northward at Charleston again (8–9 July).

German U-boats [submarines] wreaked havoc with Allied ships during the Battle of the Atlantic and on 17 August 1918, U-117, Kapitänleutnant Otto Dröscher in command, sank Nordhav about 120 miles northeast of Cape Henry, Va. Nordhav, a 2,846 ton steel-hulled four-masted bark, was operated by Bechs Rederi A/S (Carl Bech & Co.) of Tvedestrand, Norway, and carried a cargo of linseed from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to New York. Dröscher stopped Nordhav, and a boarding party planted charges on board and scuttled the vessel while her crew abandoned ship. The following evening Kearsarge reached the area and rescued all 26 survivors of the ship’s company, and returned them to safety at Boston, where the battleship operated for some time (20 August–26 October). U-117 surrendered to the Americans on 21 November 1918 (Dröscher, too, would survive the war) and in 1921 the U.S. services began a series of bombing tests off the Virginia capes. Three U.S. Navy Felixstowe F-5L flying-boats initiated the evaluations on 21 June of that year when they dropped a dozen bombs from 1,100 feet that sank U-117 in 12 minutes after the first hit.

Kearsarge -- Cmdr. George E. Gelm, her commanding officer, later received the Navy Cross for his “exceptionally meritorious service in a duty of great responsibility” for his command of the ship during the war -- joined multiple ships in New York harbor as Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels reviewed them from Mayflower’s deck, and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt reviewed them from Aztec (S. P. 590), the day after Christmas 1918.

Kearsarge continued as an engineering training ship, and accomplished repairs in dry dock at Boston Navy Yard (23–28 April 1919). Following that work, she set out for the Naval Academy (16–29 May), where she embarked midshipmen for training in the West Indies (7 June–27 August). On 9 June the battlewagon took station in a column with Alabama, Illinois, Kentucky, Maine, and Wisconsin (Battleship No. 9) as they charted courses into warmer climes. The squadron visited Guantánamo Bay (16–22 June) and St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands (25 June–1 July). They then turned westward, celebrated Independence Day at sea, and reached Colón at the Panama Canal on 5 July, and into the 7th passed through the canal to Balboa. Following the ships’ brief sojourn into the Pacific, they came about and returned through the Panama Canal into the Caribbean, and arrived back at Guantánamo Bay for another fleeing stop (12–17 July). The battleships then sailed for New York, which they reached on the 26th, and Kearsarge and additional ships continued on to Provincetown and then swung around for New York (28 July–8 August 1919). On the 11th Kearsarge and her cohorts stood out of that bustling port for the Southern Drill Grounds, where she trained the midshipmen in gunnery practice, and the battlewagons wrapped-up their shooting and returned the midshipmen to the Naval Academy, where they disembarked two days later. Kearsarge proceeded to Philadelphia Navy Yard, where she was placed out of commission on 10 May 1920.

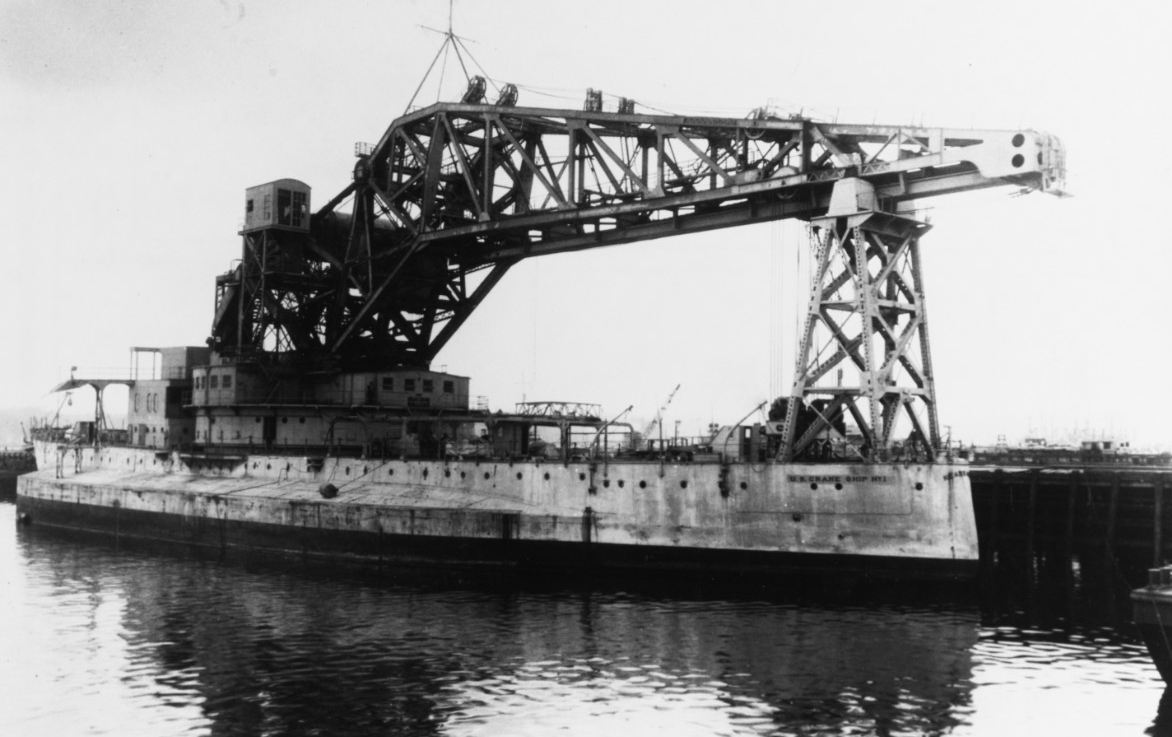

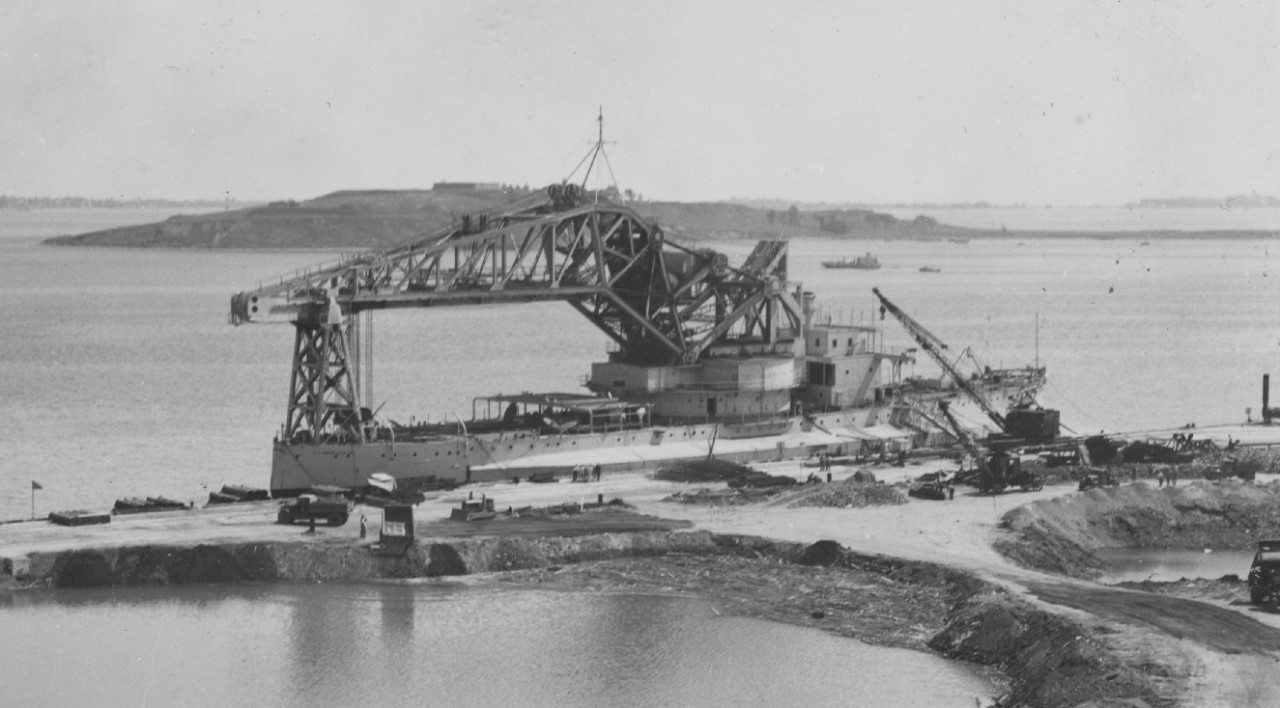

While at Philadelphia, Kearsarge was converted to a crane ship and on 5 August 1920 was renamed Crane Ship No. 1 (AB-1), which received a large revolving crane with a rated lifting capacity of 250 tons, as well as ten foot wide hull blisters which gave her more stability.

The 10,000 ton crane ship served at Boston until 1926, when ocean tug Sonoma (AT-12) took her in tow to Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash. (15 June–21 August 1926). During the following years, the ship assisted in rearming a number of battleships and heavy cruisers, helped disarm other heavy cruisers to conform with treaty limitations, and supported the navy yard as it dismantled auxiliaries.

Ten years later, however, as battleship building contracts emerged Navy planners determined that the crane ship would admirably help with the construction of new dreadnaughts on the east coast. Minesweeper Kingfisher (AM-25) moved Crane Ship No. 1 to Useless Bay at nearby Whidbey Island, and cargo ship Sirius (AK-15) then (14 May–21 June 1936) took the crane ship in tow back to New York Navy Yard, where the yard reported that it maintained her in “decommissioned status.”

Crane Ship No. 1 then shifted to Boston Navy Yard for work there, and reclassified to an auxiliary crane ship on 15 April 1939. On 21 October 1940, the vessel was assigned to the Third Naval District at New York. Capella (AK-13), Iuka (AT-37), and Sciota (AT-30) took Crane Ship No. 1 under tow to the navy yard at Boston in late July 1941.

Many people continued to fondly call her Kearsarge, however, and on 6 November 1941, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox authorized the service to drop the name Kearsarge and for her to be known only as Crane Ship No. 1. The service continued to shuttle the ship between different stations as needed and on 21 November 1941, the office of the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) authorized her to be transferred from the First Naval District at Boston to the Fifth Naval District, where the vessel was to work at Newport News Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. Capella, Sciota, and Wandank (AT-26) were to take her in tow, but Keywadin (AT-24) relieved Sciota for the trip just before Christmas 1941.

Reassigned to the Fifth Naval District on 7 May 1942, she was berthed at Norfolk on the 14th. Crane Ship No. 1 continued her service throughout World War II by handling guns, turrets, and armor for new battleships such as Alabama (BB-60) and Indiana (BB-58), heavy cruiser Chicago (CA-136), new rifled guns for the veteran Pennsylvania (BB-38), repairs to Intrepid (CV-11) and light cruiser Savannah (CL-42), and assisted in the construction of Boxer (CV-21). She was further assigned to the Fourth Naval District at Philadelphia in September 1943.

The Army required Crane Ship No. 1’s lifting services to support tugs and harbor vessels operating in New York, so early in the New Year (26–27 January 1944), War Shipping Administration (WSA) tug Hillsboro Inlet took her in tow to a berth at South Side Pier 14 on Staten Island, N.Y. Following the crane ship’s work at New York, tugboat Rescue took her in tow back to Philadelphia (13–14 May). The next month she resumed her demanding work and returned to New York, where WSA tug Rescuer took the vessel in tow back to Philadelphia. The CNO’s office reassigned her from the east to the west coast on 20 December 1944, and just after the holidays in January 1945, rescue tug ATR-84 and Trinidad Head, a tug operated by Moran Towing & Transportation Co., of New York, brought Crane Ship No. 1 through the Panama Canal to the Eleventh Naval District at San Diego, and she subsequently reached the San Francisco area.

The ship was nonetheless placed out of service at San Francisco Navy Yard’s Naval Drydocks Hunters Point on 31 April 1945, so as to free her crewmen for duties elsewhere, and civilian mariners manned the aging vessel. Crane Ship No. 1 was assigned to the Twelfth Naval District at Mare Island on 1 May 1946. On 14 May 1947, she was directed to operate from Long Beach Naval Station, Terminal Island, Calif. A flurry of activity took place as the ship shifted once again to active naval service on 6 October 1947, and on 2 April 1948, she was reassigned to the First Naval District and directed to return to the east coast and finish her career at Boston Naval Shipyard. That summer the vessel was consequently towed through the Panama Canal into the Caribbean, where fleet ocean tugs Alsea (ATF-97) and Salanin (ATF-161) rendezvoused with the ship as she rounded Cuba, and they exchanged tows and took her through the Windward Passage, reaching Boston on 23 August 1948.

Joseph McDonald, a master rigger, described Crane Ship No. 1 as “a big gray hulk of a thing” which was “pulled around by two or three tugs…But the old girl has brought millions of dollars’ worth of business to Boston. Without her we would never have been able to do many of the big jobs that cost millions of dollars.”

The former pre-dreadnaught battleship demonstrated her continued usefulness following a tragic accident on the clear calm night of 28 November 1951. At 1630 that evening fishing trawler Lynn cast off her lines from Boston’s Fish Pier, bound for the Georges Bank. Lynn was a 164-ton steel-hulled diesel-powered vessel built at Bethlehem Steel’s Fore River yard in Quincy, Mass., in 1941, and operated by R. O’Brien Co., Inc., of Boston. The Navy then (6 February 1942–15 April 1946) purchased the boat for service during World War II, and she operated along the Eastern Sea Frontier, first as coastal minesweeper AMc-201, and then as YP-388 while she worked as a district patrol vessel. The trawler returned to civilian service following the war. Another fishing trawler, Bonnie, preceded Lynn, and a third boat, Ballard, followed. All three vessels steered a course about a half mile distance between each other, and made about eight to nine knots as they approached Broad Sound.

Meanwhile at 1530, Ventura, a 10,500-ton T2 motor tanker owned by the Ventura Corp., and operated under a bare boat charter by The Texas Company, set out from the Union Oil Dock in Chelsea, bound for Eagle Point on the Delaware River in New Jersey. Ventura dropped her undocking pilot and discharged her tugs an hour later, and then continued with a qualified coastwise pilot on board, overtaking Ballard at a speed of just over 13 knots. The tanker sounded a whistle blast to Ballard, which heard it but did not answer. At about the same time, Ventura’s pilot sighted Lynn as she turned to starboard around Buoy No. 1 at the southerly side of the North Channel and shaped a course through Broad Sound toward the whistling buoy north of The Graves.

Ventura sounded her whistle twice as she overtook Lynn, which did not respond, and the tanker attempted to pass Lynn on the fishing trawler’s port side but sliced into Lynn’s port side about 24 feet forward of her stern post. The impact sheered Lynn around and Ventura had way on and continued through the collision. The trawler filled with water and sank so quickly that 13 of her 17 crewmen, who were eating supper or were otherwise below deck, were unable to escape and died. The collision threw the four men in the pilothouse into the water, but only two of them, Carl McNamara, the master, and John L. King, the helmsman, survived. The other two, Mate Jim Hayes and crewman John Rogers, entered the water but succumbed to their injuries after being rescued. Coast Guard investigators cited the tanker as in error. The Navy assisted salvage efforts the following year (4–5 September 1952) when Crane Ship No. 1 worked with Coast Guard buoy tender Cactus (WAGL-270) and commercial tug Juno of Boston Towboat and raised the sunken trawler. The salvors returned Lynn initially to South Jetty at the South Boston Annex of the Boston Naval Shipyard.

Secretary of the Navy Charles S. Thomas authorized Crane Ship No. 1’s disposal on 8 March 1955. She was stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 22 June 1955, and on 9 August 1955 sold for scrap to Patapsco Scrap Corp., of Baltimore.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Capt. William M. Folger | 20 February 1900 |

| Capt. Bowman H. McCalla | May 1901 |

| Capt. Joseph N. Hemphill | 10 May 1902 |

| Capt. Raymond P. Rodgers | 30 April 1904 |

| Capt. Herbert Winslow | 17 October 1905 |

| Capt. Hamilton Hutchins | 1 November 1907 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Nathan C. Twining | 6 February 1909 |

| Capt. Benjamin Tappan | 9 June 1909 |

| Lt. Charles H. Bullock | 21 October 1911 |

| Lt. Levin J. Wallace | 1912 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Walter G. Roper | 31 May 1913 |

| Cmdr. Julian L. Latimer | 1 January 1914 |

| Cmdr. Harley H. Christy | 23 June 1915 |

| Cmdr. Louis R. de Steiguer | 7 January 1915 |

| Cmdr. George E. Gelm | 26 June 1916 |

| Capt. John D. Wainwright | 6 March 1919 |

| Cmdr. Emil P. Svarz | 1 December 1919 |

Mark L. Evans and Paul J. Marcello

6 December 2017