Hansford (APA-106)

1944-1946

A county in Texas.

(APA-106: displacement 8,100; length 492'7 ½"; beam 69'6"; draft 26'6"; speed 16 knots; complement 479; troops 1,500; armament 2 5-inch, 8 40 millimeter, 18 20 millimeter; class Bayfield; type C3-S-A2)

Gladwin was laid down on 10 December 1943 at San Francisco, Calif., by Western Pipe & Steel Co., under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull No. 1551); launched on 25 April 1944, sponsored by Mrs. Edward C. Cahill; transferred to the Navy; renamed Hansford (APA-106) on 25August 1944; and commissioned at Pier 27 San Francisco on 12 October 1944, Cmdr. William A. Lynch in command. 1

The prospective crew assembled at the Pre-Commissioning Training Center, Treasure Island, Calif., during September and October 1944. Cmdr. Lynch also maintained an office at the Central Commissioning Detail, West Coast, where he carried out many of the details necessary to commission the ship. Hansford concluded her final drydocking prior to commissioning at Hunters Point Naval Drydock, San Francisco, on 5 October, and successfully completed her sea trials on 9 October.

The ship’s designed boat capacity consisted of 22 landing craft, vehicle, personnel (LCVP); one landing craft, support (small) (LCS), not initially differentiated in the ship’s Command History Report between Mk I or Mk II, but later exchanged for an additional LCVP, one landing craft, personnel, ramped (LCPR); one landing craft, logistic (LCL); and four landing craft, mechanized, Mk III (LCM(3), later exchanged for four LCM(6)s). The vessel also initially carried 44 life rafts with a capacity of 60 men each.

Following the ship’s commissioning ceremony that began at 1500 on 12 October 1944, Hansford made for Naval Supply Depot, Oakland, where she spent four days outfitting. While the ship moored at Oakland, the three officers and 39 enlisted men of her Beach Party, Lt. Cmdr. James H. Ottley, USNR, commanding, reported on board.

Hansford loaded ammunition in San Francisco Bay on 16 October 1944. The following evening, the attack transport underwent deperming and degaussing tests at Pier 31 San Francisco. She swung for compass compensation and calibration on 18 October. The ship lay at anchor in the bay for the next week, with the exception of completing her radar calibration at Hunter’s Point on the morning of 20 October. On 23 October, the attack transport reported for her shakedown off San Pedro, Calif. She carried out structural firing tests on all her guns during the voyage, and operated under the command of the San Pedro Shakedown Group from 24 October to 10 November. The ship carried out a variety of drills and maneuvers during her shakedown, including speed runs, tests for tactical data, gunnery exercises, and damage control drills. Hansford completed boat drills and landing exercises as part of the amphibious portion of her shakedown, in the vicinity of San Diego, Calif., from 4 to 10 November.

She then completed her post shakedown availability at Terminal Island Navy Yard, Long Beach, Calif., from 11 through 19 November 1944. The work included a number of alterations and repairs, as well as camouflaging the exterior of the ship. Hansford completed her shakedown and then sailed for San Francisco on 20 November, arriving the following day. The ship loaded 2,400 tons of naval cargo at Navy Pier 2 Oakland, and on 25 November embarked 220 naval passengers at Pier 56 San Francisco. Hansford sailed for Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands in company with three other ships and one escort on the afternoon of 25 November. These ships steamed as part of Task Unit (TU) 16.1.16, Hansford assumed tactical command. The convoy rendezvoused with three additional ships and two escorts from a detachment of the task unit that sailed from Port Hueneme, Calif., the following day. Attack transport Napa (APA-157), which embarked Seabees and cargo of the 30th Naval Construction Battalion, assumed tactical command of the combined convoy. One of the escorts prosecuted an apparent underwater sound contact, that did not develop, on 28 November. The voyage otherwise proved uneventful, and the ships carried out gunnery target practice while en route to Hawaiian waters.

Hansford disembarked her passengers and unloaded her cargo at Naval Supply Depot, Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii (T.H.), on 2 December 1944. The ship remained moored at the depot through 5 December, when she shifted to mooring buoys in the harbor. While in Hawaiian waters, Hansford sailed as part of TU 13.10.8 during an intensive training program emphasizing landing exercises during daylight and maneuvering while in formation at night, in the vicinity of the islands of Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Maui. The ship carried out those exercises under simulated battle conditions, including air attacks, as well as practicing streaming paravanes, generating protective smoke, and passing mail. In addition, she conducted antiaircraft practice while steaming to and from the exercises.

The ship moored to buoys at Pearl Harbor from 17 to 28 December 1944. Crewmen enjoyed regular recreation and liberty excursions ashore. The ship’s orchestra and a series of skits performed by crewmembers entertained the crew during a special Christmas Eve program, and the following day they further celebrated Christmas with worship services and a turkey dinner. The vessel also arranged for nightly showing of films for the crew while in port. During this period, the ship served within Transport Squadron 16 as part of Transport Division 47, whose flags flew in attack transports Cecil (APA-96) and Rutland (APA-192), respectively.

Hansford proceeded to Hilo, T.H., and embarked 1,055 Marines and their assigned hospital corpsmen and 595.44 short tons of the 1st Battalion Landing Team, 27th Regiment, 5th Division, on 28 December 1944. The ship and her embarked Marines then carried out amphibious training in the vicinity of Maui from 31 December 1944 to 2 January 1945. From 3 to 12 January 1945, the attack transport moored at Pearl Harbor. She then sailed as part of Transport Group Able, Task Force (TF) 53.1, for further training maneuvers in the vicinity of Maui from 12 to 18 January. Those exercises were similar to the previous training undertaken by the ship, but on a larger scale. The ship returned to Pearl Harbor.

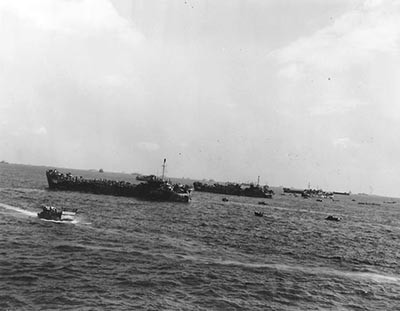

Hansford sailed as part of Transport Group Able, TF 53.1, for Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands on 27 January 1945. The ship arrived at Eniwetok on 5 February, having dropped a day in crossing the International Date Line. Hansford conducted target practice and damage control drills during the voyage, and accepted a patient transferred from a destroyer for further medical treatment. The ship fueled and provisioned while at Eniwetok, and two days later made for the Marianas Islands, arriving off Saipan on the morning of 11 February in the staging area for Operation Detachment, amphibious landings on lō-tō (Sulfur Island, identified by the Americans as Iwo Jima) in the Kazan Rettō (Volcano Islands) by the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions. The attack transport took part in the final rehearsal for the landings while at Saipan, shifting men and gear between several tank landing ships (LSTs). A Japanese air raid struck the area while the ship operated at Saipan, but the enemy did not attack Hansford.

The ship sortied with TF 51 on 16 February 1945. Navy Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberators and USAAF Boeing B-29 Superfortresses flying from the Marianas augmented carrier air patrols that swept the seas ahead of the ships to prevent their discovery. During that operation, the ships of TF 58, Vice Adm. Mark A. Mitscher commanding, including nine fleet and five small carriers, and a night group of two fleet carriers, also launched the first carrier attack against Honshū, Japan. The raid served as a diversion for the landings on Iwo Jima, and to weaken the Japanese air strength sufficiently to preclude their counterattacks against the invasion armada.

Planes bombed Japanese aircraft factories, airfields, and ships around the Tōkyō area. Heavy clouds and snow and rain squalls impeded operations, but a momentary break in the weather enabled scores of U.S. and Japanese fighters to mêlée east of the capital. Foul weather persuaded Mitscher to cancel attacks and return to support the landings on 17 February 1945. Planes also flew neutralization strikes against the Bonins.

Previous carrier raids and USAAF B-24 Liberator and Superfortress missions flown from the Marianas had weakened but warned the Japanese defenders, and the garrison prepared extensive defenses utilizing the island’s caves. The volcanic terrain limited the effectiveness of all but direct hits against those positions, and the Marines consequently sustained appalling casualties. The initial assault waves that stormed the beaches of Iwo Jima included men landed from Hansford on 19 February 1945. The sky was overcast by low clouds but with good visibility, and a light northeast breeze touched the morning, shifting to the southeast in the afternoon. The weather provided nearly ideal conditions for the landings. The sun rose at 0707 and set at 1831.

At times during the Battle of Iwo Jima, the ships and boats operating in the roadstead contended with Japanese fire from shore, aerial counterattacks including kamikaze (God wind, commonly translated as divine wind) suicide planes, and submarine attacks including kaiten (Return to the Sky) manned suicide torpedoes. Hansford steamed as part of TF 53.1.2 within TF 53, the Attack Force, Rear Adm. Harry W. Hill commanding. Vice Adm. Richmond K. Turner held the overall command of the landing forces within TF 51, the Joint Expeditionary Force.

The ship set General Quarters at 0500 and nine minutes later set Condition One-Able. She arrived in the transport area about 18,000 yards off the southeast beaches of Iwo Jima at 0630, and seven minutes later commenced launching boats, debarking Marines of the assault waves and their equipment, as well as the ship’s beach party. Hansford maneuvered throughout the day to keep position on Rutland, the division flagship. The ship received her first casualties evacuated from the beach at 1700, and then retired from the transport area for night, maneuvering in the vicinity of Iwo Jima and Minami-lō-tō (South Sulfur Island).

Hansford continued to land men and equipment during the fighting, often closing to within 1,000 yards of land in spite of enemy fire. At one point, the attack transport avoided damage from mortar rounds that splashed within a few hundred yards of her. In addition, the soft sand and volcanic ash of the island bogged down vehicles, and in combination with a steep, quick-breaking single line of breakers averaging four feet in height, shell holes, and tank traps, impeded the landing. Hansford lost two LCVPs and two LCMs operating from the ship.

Hansford’s beach party fought ashore from the morning of 19 February 1945 to 0915 on 23 February. Japanese mortar and small arms fire pinned them down on the first day of the landings, and a mortar round struck part of the command post, destroying an [Army] Signal Corps Radio 610 set. The intense enemy fire prevented the men from working cargo, and they succeeded only in unloading some of the boats in order to use them to evacuate casualties before nightfall. The beach party suffered 15 casualties, including four dead, on D-day.

The Marines pushed further inland on D plus 1. The Japanese fire consequently lessened, and the men on the beach worked in between the spasmodic mortar and sniper fire. The casualties to date, however, required the reorganization of the beach party. In addition, the men labored to clear the water’s edge of cargo and stalled vehicles, in order to unload boats. The chaotic conditions imperiled the process, and arriving coxswains received orders to avoid the beach until summoned by the Beachmaster. Only boats carrying high priority cargoes landed, principally those carrying limited amounts of small arms ammunition, mortar ammunition, flame throwing material, water, and rations. Some of the boat crews anxiously attempted to escape from the carnage as quickly as possible and unloaded their cargoes without line handling or shore party teams. Their actions added to the casualties and to the wreckage cluttering the area. At 1600 the ship succinctly reported that such materials “clotted” the beach.

Lt. Comdr. Ottley of the beach party subsequently received the Bronze Star for his actions as Beachmaster during the fighting on Red Beach Two from 19 to 23 February, when “…despite the heavy enemy mortar and automatic weapons fire, which had caused severe casualties among his group,” Ottley had “voluntarily remained on the beach after the balance of his party had been relieved and, by his cool and capable direction, continued to direct the landing of vital cargo on the beach,” demonstrating laudable “ leadership, courage and devotion to duty”2

The ship’s Beach Party suffered a total of 17 casualties (all USNR) during the Battle of Iwo Jima: Lt. John H. Dunn while serving as the Beach Party Assistant Beachmaster, Radioman 3d Class Charles S. Anderson, Radioman 3d Class Donald S. Hansen, and Seaman 1st Class Henry Brozozowski killed; one bluejacket, Coxswain William Schiefer, missing; and 12 men wounded; Lt. Edwin D. Richards (MC), Chief Boatswain Mate Charles H. Pryor, Shipfitter 1st Class Howard W. Lee, Boatswain Mate 2d Class Roland P. Olsen, Carpenter’s Mate 2d Class Ray W. Scott, Carpenter’s Mate 3d Class William L. Alvey, Radioman 3d Class Leo J. Kepka, Seaman 1st Class Rosario Bucini, Seaman 2d Class Dean R. Broach, Seaman 2d Class Joseph R. Johnson, Seaman 2d Class Alvin N. Kittle, and Seaman 2d Class Earl J. Mitchell. In addition, three members of the boat group suffered wounds; Motor Machinist’s Mate 3d Class David L. Lutes, Seaman 1st Class Benjamin Bromgard, and Seaman 2d Class John F. Griffin.

“The beach condition at Iwo Jima stressed the weakness of our present beach party organization,” an observer later wrote in COMINCH P-0012 Amphibious Operations Capture of Iwo Jima 16 February to 16 March 1945, “Practically all members of the beach parties were engaged in their first combat experience. The beach conditions were unusually tough and would have challenged the resourcefulness and efficiency of the most highly trained organization…” The calm weather during the initial landings facilitated the establishment of the perimeter ashore, heavy surf would have swamped many of the bogged down landing craft and added to the casualties

Hansford’'s proximity to shore enabled her men to observe the carnage at close hand. Each day while Hansford lay anchored offshore, she also embarked and cared for wounded evacuated from the beaches. The attack transport received 59 combat casualties during the forenoon watch on 23 February, followed by 63 additional wounded during the afternoon watch. The ship transferred 200 rounds of 5-inch/38 cal. antiaircraft ammunition to infantry landing craft LCI-624 for redistribution to destroyers during the forenoon watch on 24 February. Later that evening, she embarked 54 wounded evacuated from the fighting ashore.

At 1237 the following day [24 February 1945], LCI(L)-347 struck Hansford’s port side while she came alongside. The impact ruptured a plate on the attack transport and caused a hole in the hull, which the crew subsequently repaired. Meanwhile, the ship anchored and transferred 74 ambulatory casualties to attack transport Lenawee (APA-195), along with 23 more wounded , beginning at 1523. A further seven wounded arrived on board during the afternoon watch.

The attack transport sailed as part of TU 51.16.4 for Saipan on the afternoon of 25 February 1945, the following day burying at sea three Marines wounded ashore but who died on board. An escort prosecuted two underwater sound contacts but did not attack the suspected submarine on 26 February. The ship transferred 127 casualties to an Army hospital upon her arrival there three days later on 28 February. A crippled B-29 named Dinah Might made the first of more than 2,251 Superfortress emergency landings on the island by the end of the war, on 4 March. The U.S. declared Iwo Jima secured on 16 March.

Hansford meanwhile departed in company with ships of Transport Squadron 16 for Tulagi in the Solomon Islands on 5 March 1945. During the voyage, escorts made two contacts on apparent submarines, but neither resulted in battles. The ship also crossed the equator while en route on 9 March 1945, engaging in the traditional ceremonies wherein “all found worthy were inducted into the ancient Order of Shellbacks.”

The attack transport reached Tulagi on 12 March 1945. While at Tulagi, the ship replaced the boats she had lost at Iwo Jima. She sailed for the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) the following day, anchoring at 1240 on 15 March in Berth 9, Segond Channel, Espiritu Santo. At 1355, the ship shifted berths, mooring starboard side to Dock 5 Chaverst Point at 1435. Hansford then embarked 1,164 soldiers and 1,044.18 short tons of cargo of the Army’s 2d Battalion Landing Team (BLT), 105th Regiment, 27th Infantry Division, on 18 and 19 March. While at Espiritu Santo, Hansford readied herself for further combat, though the ship’s historian also noted that “the supply of beer carried aboard for the use of the ship’s company ashore was especially needed and used.” On 25 March, the ship sailed in company with Task Group (TG) 51.3 for Ulithi atoll, the staging area for Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa in the Ryūkyū Islands. Cecil served as the convoy’s guide. Hansford practiced antiaircraft gunnery on 25 March, and during the voyage the convoy’s escorts reported a total of six submarine contacts, though none proved to be identifiable to warrant antisubmarine actions. The attack transport anchored at Berth J. Ulithi at 1155 on 3 April, and fueled and provisioned.

At 0555 the following day, Hansford went alongside oiler Schuylkill (AO-76) in Berth 18, moored starboard side to her at 0614, and received fuel. At 0838, Hansford sortied with TG 51.3, in obedience to Operational Plan A5-45X of 3 April 1945, to the Ryūkyūs to take part in the follow up phases of the invasion of Okinawa. Destroyer escort Connolly (DE-306) reported a surface contact at 2303. The ships of the convoy carried out emergency maneuvers, but the target proved to be a derelict landing craft. The escorts sank the vessel with gunfire to prevent her from becoming a hazard to navigation. En route, the task group also encountered three submarine contacts, as well as numerous floating mines that necessitated emergency maneuvers. Hansford anchored in Kerama Rettō on 9 April 1945.

Hansford lay initially at the northwest anchorage and then shifted to the inner harbor. The following day, the ship steamed to the Hagushi beaches at Okinawa, acting as Officer in Tactical Command and guide for four other ships of Transport Division 47: attack transports Carteret (APA-70) and Sandoval (APA-194), and attack cargo ships New Hanover (AKA-73) and Yancey (AKA-93). Hansford anchored in Berth H-157 Hagushi Anchorage at 1136. At 1455, she began to unload troops and cargo. While the ship lay off Hagushi, she also embarked casualties from the beach.

As the ships steamed toward the battle, the Japanese launched an aerial counteroffensive, consisting of a series of ten massed kamikaze attacks, interspersed with smaller raids and named Kikusui (Floating Chrysanthemum) No. 1, against the Allied ships operating off Okinawa. The first such raid occurred on 6 April 1945, partially in combination with Operation Ten-Go, the dispatch of the First Diversion Attack Force, including battleship Yamato, across the East China Sea toward Okinawa to lure U.S. carriers from the island, and to facilitate kamikaze attacks. In total, the Japanese utilized an estimated 1,465 aircraft during those strikes through 28 May.

Men on board Hansford repeatedly sighted Japanese planes that attacked ships in the area during a series of 20 air raids that took place that week. The crew went to General Quarters three times during their first full day at Hagushi, from 1023 to 1045, 1343 to 1354, and 2025 to 2110 on 11 April. The following day, Japanese planes raided the ships in the roadstead heavily. Hansford sounded General Quarters from 0047 to 0104, 0340 to 0617, 1405 to 1718, and 1948 to 2215. The enemy incessantly harried the ships off Hagushi, and the ship’s gunners fired their 20 millimeter and 40 millimeter antiaircraft guns at single Japanese planes that twice passed close aboard at extremely low altitudes at 0417 and again at 0451, though without apparent effect. The ship’s company suffered their only casualty during the Battle of Okinawa when the barrel of a 20 millimeter gun exploded during this air raid, wounding Seaman 1st Class Marvin L. Craft, USNR. The attack transport disembarked some of her troops during the afternoon watch, and that evening embarked ten casualties evacuated from the fighting ashore.

The enemy air raids continued, and Hansford manned her Battle Stations from 0315 to 0545, 1749 to 1803, 1933 to 2012, 2111 to 2144, and 2208 to 2237 on 13 April. No enemy planes approached the ship directly, but her crew witnessed the desperate plight of other ships under attack during many of these raids. During the air raids that occurred at night, Hansford and her boats generated smoke. The ship assigned a boat each evening to cover one of the other ships in the roadstead with smoke.

Hansford sailed from the Okinawa area in company with TU 51.29.16 with 51 casualties on board on 16 April. A large force of Japanese planes attacked the ships off Okinawa during the convoy’s departure. An enemy Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 land attack plane approached the formation, but USMC Vought F4U Corsairs splashed the Betty. During the voyage, the escorts also gained Sound Navigation And Ranging (SONAR) echoes on two separate occasions, but did not develop the potential submarine contacts.

The ship transferred her embarked wounded to an Army hospital upon arrival at Saipan, during the afternoon watch on 20 April 1945. The next day she stood out with Transport Squadron 16 for Ulithi, where she anchored on 23 April to commence a month of training for future operations against the Japanese home islands. The ships of the squadron held an antiaircraft target practice competition; and at one point Hansford’s gunners won a consignment of beer from the other ships by demonstrating their proficiency against the target sleeves. Japanese planes raided the atoll twice during this period, but neither raid approached the area where Hansford lay anchored.

The attack transport sailed from Ulithi on 22 May 1945, reaching Guam the next day. The ship acquired four LCM(6)’s, and at 1550 on 23 May, proceeded to the Philippines, anchoring at Berth 415 San Pedro Bay, Leyte Gulf, at 0814 on 27 May. During the subsequent weeks, Hansford continued her preparations for the invasion of Japan, often as part of Transport Squadron 16.

Hansford sailed from San Pedro Bay in company with ships of Transport Squadron 16, at 0702 on 29 May 1945. Cecil again operated as the guide and Officer in Tactical Command (OTC). Hansford anchored at Berth 57 Subic Bay at 0937 on 31 May. The attack transport experienced two Japanese air raids while at that port, but no enemy planes appeared within visual range of the ship. The crewmembers otherwise pursued liberty ashore, and softball teams from Hansford competed against teams from other ships.

The ship then sailed with a convoy for Manila at 0653 on 13 June 1945, Rutland acting as the guide and OTC. Hansford conducted antiaircraft target practice during the morning watch, firing 27 rounds of 5-inch/38 caliber; 130 cartridges of 40 millimeter; and 484 cartridges of 20 millimeter ammunition. The ship anchored at Berth 30 Manila at 1712 that day. Hansford served with Transport Division 47 while at Manila, and recorded a Japanese air raid, but again did not spot enemy planes overhead. She stood out of Manila Bay on 17 June, returned to Subic the next day, on the morning of 21 June carried out a landing exercise, and then made for Leyte Gulf at 0748 on 26 June. Rutland again served as the guide and OTC of the convoy.

Upon the ship’s arrival at Leyte Gulf two days later, she operated with Transport Division 47, and practiced with soldiers of the Army’s 81st Infantry Division. The ship commenced her training with the men of the 1st and 3d BLTs, 321st Infantry, followed by the 3d BLT, 323rd Infantry, and then the 3d BLT, 322d Infantry. During these exercises, the vessel embarked the soldiers and their gear at Tarraguna, and carried out the training at Hinunangan Bay in southern Leyte. The ship got underway at 1055 on 17 July 1945, and at 1332 anchored in Berth NN Silago Cove, Leyte.

Hansford sailed to San Pedro Bay at 0622 on 22 July 1945, stopping en route at Guiuan in eastern Samar at 1043 to receive four LCM(6)s. The ship then stood out at 1649, anchoring in Berth 107 San Pedro Bay at 1950. The attack transport made for Iloilo City, Panay, in the Western Visayas, at 0745 on 26 July, arriving the following day. While there, she trained with soldiers of the Army’s 40th Infantry Division. The ship anchored east of Miagao Point on the south coast of Panay at 1125. The advanced echelon of the 2d BLT, 108th Infantry Regiment, embarked during the first of the exercises, at 1810 on 29 July. The following morning, the ship loaded cargo for these men, as well as her own beach party, and then the remaining men during the afternoon.

The ship sailed at 1256 on 31 July 1945, anchoring at 1700 in Panay Gulf off Diut Point, Negros Island. At 0634 the following day, Hansford steamed into the T-4 landing exercise. Rutland coordinated the action as OTC. Hansford began to land her embarked soldiers at 0737, and they seized a beachhead near Cauayan on the north coast of Negros Island. The ship proceeded independently at 1245, anchoring in her previous berth off Diut Point at 1337. She conducted additional landing exercises off Miagao Point during the succeeding days, at one point landing soldiers of the 2d BLT, 160th Infantry. Hansford returned independently to Manila on 13 August, arriving the following day.

The Japanese accepted the terms of unconditional surrender on 15 August 1945—14 August in the U.S. President Harry S. Truman announced the end of the war in the Pacific, and the Allies celebrated V-J [Victory in Japan] Day. Hansford embarked Rear Adm. John L. Hall, Jr., Commander Amphibious Group 12, and his staff of 62 officers and 218 bluejackets, on 16 and 17 August.

The attack transport embarked 911 soldiers and loaded 541.8 short tons of cargo for their passage to commence occupation duty in Japan, on 19 August 1945. The following morning at 0845, she moored starboard side to Pier 5. Hansford then embarked additional soldiers. In total, the men she embarked during these two loading evolutions originated from a variety of commands—primarily of the XI Corps—including the Headquarters of the 68th Antiaircraft Artillery Brigade; Headquarters of the 35th Antiaircraft Artillery Group; 161st and 382d Antiaircraft Artillery Battalions; and the Counter Intelligence Corps.

The ship steamed to Batangas Bay, Luzon, at 0555 on 24 August 1945, anchoring there at 1347. The attack transport sailed with TF 33 for Tōkyō Bay at 0819 the following day. Hansford held the tactical command of the force. The convoy rendezvoused with Transport Division 65 at 1645, but at 2310 the combined ships came about and returned to Subic Bay because of Typhoon Ruth, which swept across the area with winds reaching a recorded peak of 130 knots. Hansford resumed her voyage to Japanese waters at 0857 on 27 August, the ship again acting as the guide and OTC. Her lookouts occasionally sighted floating mines—which the ship passed at a safe distance. On that date ships of the Third Fleet, Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr., commanding, steamed into Sagami Wan outside the entrance to Tōkyō Bay. Aircraft carriers protected the vessels by launching planes that flew reconnaissance missions over the Japanese homeland, while the carriers steamed outside the bay.

The Japanese formally surrendered on board battleship Missouri (BB-63)in Tōkyō Bay on 2 September 1945. Early that morning, Hansford sailed as part of the Allied armada that entered the bay, passing Missouriabeam to starboard as the surrender ceremonies commenced. The following day, Hansford disembarked occupation troops at Yokohama. The ship remained either alongside a dock or at a mooring buoy during the succeeding days. On one night, the ship provided quarters for several hundred former Allied prisoners-of-war liberated from the Japanese. These men emerged from their captivity emaciated and weakened from enemy neglect and brutality, and thus required compassionate care from the crewmembers. While moored alongside the Customs House Pier at Yokohama, the ship also converted a building at the pier into what her crewmembers dubbed ‘The Eager Beaver Tavern.’ The attack transport reported that the establishment provided “copious quantities of beer” for the ship’s company and staff members on liberty. Hansford shifted to reserve status in the Pacific Fleet on 11 September.

Hansford berthed at Wakayama, Honshū, on 2 October 1945. Amphibious force flagship Auburn (AGC-10) served as a flagship for amphibious forces during this period, arranging ship-to-shore communications and facilities for occupation troops. The ship arrived alongside Hansford at 0909 on 4 October, and Adm. Hall transferred from Hansford to Auburn. At 1441, Auburn cast off, and at 1625 Hansford began receiving passengers for their return to the U.S. At 0701 the following day, the ship shifted her berths to avoid an approaching storm, anchoring in Berth T-12 at 0800. The attack transport sailed with seven officers and 520 enlisted passengers embarked for Yokohama at 0652 on 7 October, anchoring south of Berth E-94 Tōkyō Bay, at 1327 the following day.

In 1944 and 1945, the U.S. devised a point system intended to facilitate the transition of millions of veterans from their military service to civilian life. Veterans received a certain number of points based upon their combat experiences, months in service, time spent overseas, and so forth. The efforts to arrange for the return of these men thus produced an enormous logistics burden, stripping commands of experienced servicemembers and re-routing others to replace them—many of whom bitterly resented the orders that prevented their return home.

Operation Magic Carpet commenced—the return of these veterans from the war zones by ships and planes. Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, announced the assignment of aircraft carrier Saratoga (CV-3) and 18 small and escort aircraft carriers to troop transport duty across the Pacific on 7 September 1945. An additional 40 small and escort aircraft carriers and 197 attack transports were scheduled to embark returning veterans, following the release of these ships from moving planes and troops from the Philippines, Marianas, and Ryūkyūs into Japan. The notice added 256 ships to the 48 large transports already earmarked for Magic Carpet. The vessels that eventually transported returning veterans included some of the Essex (CV-9) class aircraft carriers and Iowa (BB-61) class battleships.

Hansford began to receive passengers as part of Magic Carpet at 0957 on 9 October 1945. The ship put to sea with 79 officers and 1,320 enlisted passengers for San Francisco at 0658 on 13 October. She sailed by a Great Circle Route, changed course during the voyage, and disembarked her passengers in San Pedro on 26 October. The attack transport completed repairs in drydock at Consolidated Steel Corp., Wilmington, Calif., from 31 October to 18 November. On that date, the ship departed for her return to Japanese waters, destroying a mine with gunfire on 1 December, and arriving at Nagoya on 4 December. The attack transport then set out with another load of troops on 7 December, disembarking the men when she moored in Seattle, Wash., on 19 and 20 December 1945. The ship completed repairs to her propeller in drydock at Todd Shipyards of William H. Todd Corp., Seattle. Hansford sailed without passengers from Seattle on 5 January 1946, anchoring in Tōkyō Bay in the vicinity of Yokosuka on 20 January.

The ship embarked 850 men who had received orders to relieve veterans who possessed sufficient points to discharge from the armed forces, setting out for Chinese waters on 1 February 1946. The attack transport disembarked her passengers in Shanghai on 4 February, sailing from that port with a handful of naval officers as passengers on 12 February. The following day, the ship disembarked her passengers at Sasebo, Kyūshū, Japan. Hansford then stood out of Sasebo, carrying what Ensign Robert Praver of the ship’s company afterward recalled as “a full capacity of Marine passengers” on 26 February.

The Navy originally intended to decommission Hansford and redeliver her to the War Shipping Administration (WSA) at the New York Naval Shipyard. Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, Commander in Chief Atlantic Fleet, however, ordered the ship diverted to Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Va., on 4 March. The attack transport concluded her Magic Carpet duty with the disembarkation of Marines at San Diego on 13 March.

On 15 April 1946, Hansford sailed from San Diego for her decommissioning at Norfolk. The ship headed for the Panama Canal Zone, reaching Balboa on 23 April. The attack transport sailed from the Canal Zone on 27 April, and arrived at Norfolk on 2 May. Hansford was decommissioned at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, Portsmouth, Va., on 14 June 1946. The ship was stricken from the Navy List on 3 July 1946, redelivered to the WSA the following day, and on 20 May 1947 sold to Isthmian Lines. The shipping company renamed Hansford as Steel Apprentice, and the vessel continued to ply the global trade routes during the post-war period.

A boiler fire in January 1949 required the subsequent renewal of four boiler economizer tube elements, and the partial renewal of casings and brickwork, totaling $10,235 in repairs. The ship collided with a barge in July the following year, necessitating repairs to the propeller and shaft renewal costing $17,000. Steel Apprentice damaged the propeller when she struck a fender on 16 January 1951. The vessel completed repairs—including fit spare and draw shaft—at Baltimore, Md. Steel Apprentice made for Belawan, Sumatra, Indonesia, but collided with steamship Ninfeasa at Saigon, French Indochina (Vietnam), on 6 February 1952. Neither ship sustained serious damage. Steel Apprentice damaged her propeller when she struck a dock on 18 September 1952. The following summer, the ship completed repairs that included reconditioning the propeller and replacing the tailshaft while in drydock at Baltimore.

Steel Apprentice then sailed to the Persian Gulf. The ship incurred two noteworthy problems during her return voyage carrying a load of ore to Baltimore. The former attack transport ran aground at Bandar Shahpur, Iran, on 8 October 1953. The ship then made for Philadelphia, Penn., but encountered thick fog in Delaware Bay on 20 October. Steel Apprentice reduced her speed and passed Miah Maull Lighthouse, but in the dense fog the bridge crew failed to spot Elbow of Cross Ledge Light at Fortescue, N.J.—the ship’s radar was also apparently inoperable.

Steel Apprentice collided with the lighthouse, toppling the upper two-thirds of the structure into the bay and damaging the caisson. Mack Construction of Cape May, N.J., demolished the debris of the lighthouse and installed a skeleton tower atop the caisson foundation, completing the project the following year. Steel Apprentice suffered substantial damage to 16 plates and 68 frames. The ship completed repairs at Baltimore, from 24 November 1953 to 3 March 1954. The repairs included the renewal of the damaged frames and plates, as well as to the rudder stock, and work on the open high pressure turbine.

The ship spent the rest of the year plying her trade along the East Coast, but her propeller accidentally tore open the side of tug Eugene T. Meseck, when she pinned the tug against the sea wall in Erie Basin on 21 December 1954. Tug Mary Moran took Eugene T. Meseck in tow to Pier A, but the stricken vessel sank in 30 feet of water. All of the crewmembers survived the sinking. Steel Apprentice sailed that night for Philadelphia and then Norfolk. Derrick barge Monarch subsequently raised and salved Eugene T. Meseck.

Steel Apprentice sailed without major incident during the following two years, though the collision with the tug required her to undertake repairs that included the renewal of one side plate, frames, and brackets at Baltimore in July 1955. On 8 February 1956, Steel Apprentice entered Suez Roads, Egypt, while en route from Manila to New York. At 2153 the ship collided with merchant vessel Jalazad, en route from Bombay, India, to the United Kingdom. The impact slightly damaged the bow of Steel Apprentice, but heavily damaged the hull of Jalazad, which temporarily suspended her voyage while affecting repairs at Suez. Steel Apprentice thus continued onward as part of a night convoy, passing through the Suez Canal. The ship completed temporary repairs at Port Said on 13 February, attained a seaworthy certificate, and sailed for Halifax, Canada, and from there to New York. The vessel completed repairs at New York that included the renewal of five bow plates and partial renewal of three more.

Heavy seas damaged Steel Apprentice while she sailed from New York to Houston, Tex., overnight on 16 and 17 April 1958. The ship completed repairs at Baltimore the following January, including the renewal of three bottom shell plates, but the surveyor evaluated the damages to the ship as “cumulative”—resulting from years of steaming upon the high seas. She undertook additional repairs in July at Brooklyn, New York. Steel Apprentice spent the next seven years sailing in relatively uneventful global trade.

Motor tank barge Sikatuna collided with Steel Apprentice while moving alongside the ship to bunker her at an outer anchorage at Manila on 7 June 1966. Steel Apprentice subsequently returned to Baltimore, and then sailed for Penang, Malaysia. Steel Apprentice put into Philadelphia while en route, and tugs Saturn and Venus assisted the loaded ship to a pier, but the shipstruck the pier on 19 September 1966. The following month, the ship completed repairs at New York. The former attack transport again undertook repairs at New York, in conjunction with the damage sustained during her collision with Sikatuna, commencing on 6 February 1967, followed by additional work resulting from the damage sustained from her impact with the pier at Philadelphia, which occurred at New York starting on 31 May.

Steel Apprentice next took part in the U.S. build-up of forces in Southeast Asia. The former attack transport sailed from Galveston, Tex., but collided on her port side with steamer Sylvia Lykes, registered with the Lykes Brothers Steam Co., while maneuvering in the Sông Sài Gòn (Saigon River) at Saigon, South Vietnam, on 27 July 1967. A survey subsequently carried out at Coos Bay, Ore., and Seattle, revealed severe damage to the port side upper shell plating and “internal parts.” The following month, Steel Apprentice completed repairs at Yokohama, including setting in nine port side shell plates in way of Nos 3 and 4 holds, and work on buckled bulkheads between No. 3 hold and the refrigerator-room.

The Communists launched a major offensive against the Americans, South Vietnamese, and their allies, that coincided with the Vietnamese lunar holiday of Tet on 30 and 31 January 1968. The enemy followed this push with additional operations, including an offensive on 4 May. Americans veterans referred to that further fighting as ‘Little Tet,’ but despite the diminutive name, fierce fighting raged across Southeast Asia. The attackers focused on Saigon and on the eastern section of the Demilitarized Zone between the North and South Vietnamese borders, but throughout May attacked more than 100 installations and cities, including almost nightly rocket and mortar salvoes and perimeter probes. The U.S. countered with spoiling attacks, and the fighting continued into the summer.

Throughout this period, the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) repeatedly attacked ships while they transited the 35-mile channel between Saigon and the South China Sea. At one point, the Military Sea Transportation Service issued a list of 48 precautions to be taken by crewmembers of these ships, including: bridge watchstanders were to wear helmets and flak vests; sailors were to stack sandbags around the bridge for protection but to leave the wheelhouse doors and windows open; secure grenade screens to portholes; ready tow wires for tow without the assistance of the crewmembers (a sobering realization of their likely plight in such an event); ready anchors for dropping; ready fire-fighting equipment; warm-up bilge and ballast pumps; the purser was to stand by with a full medical kit; and off duty sailors were to spread out in alleyways, in order to reduce casualties when the ships sustained damage. Whenever the enemy attacked, the engineers were to go to full engine speed, without notifying the bridge.

The PLAF fired rockets—most likely B-40s (RPG-2 manually operated antitank grenade launchers)—at Steel Apprentice and Gretna Victory while the ships lay in the Saigon River on the morning of 5 June 1968. The attack seriously wounded six dockside workers, damaged the hull of Steel Apprentice, and broke the port boom No. 2 hatch and damaged rigging on board Gretna Victory. The insurgents disengaged and fled, and both ships subsequently completed repairs.

Steel Apprentice continued to ply the world’s oceans until she collided with merchant vessel Arcadia Wien while en route from Kolkata (Calcutta), India, to Houston, on 3 February 1972. Isthmian Lines had the ship surveyed, and the surveyor evidently considered that the years of operation and damage sustained from accidents to preclude further salvage or operations. The ship consequently sailed from Houston for Asian waters, arriving at Yokohama on 5 April 1973, and on 21 April at Kaohsiung, Taiwan. The company sold Steel Apprentice to Tai Kien Industry Co., Ltd., on 4 May. The following month, Isthmian Lines reported the sale of Steel Apprentice to the Republic of China, and the subsequent scrapping of the ship.

Hansford earned two battle stars for her World War II service, as well as the Navy Occupation Service Medal, Asia (2 September–12 October 1945, and 3–8 December 1945), the China Service Medal, and the Navy Occupation Service Medal (19 January–26 February 1946).

Rewritten and expanded by Mark L. Evans

1. Lynch -- born in Boston, Mass., on 25 October 1895 -- enlisted in the U.S. Navy on 20 January 1912. He served during the Mexican Expedition in 1914, on board Pennsylvania (Battleship No. 38) and mine planter Shawmut (Id. No. 1255) during WWI, and on board 12 ships and submarines and at seven shore establishments during the 1920s and 30s. He thus brought more than two decades of naval service and experience to the command of Hansford. Lynch accepted an appointment as ensign on 6 June 1919, lieutenant junior grade on 31 December 1921, lieutenant commander on 1 July 1939, and commander on 17 July 1942. Following WWII, he attained the rank of captain on 10 December 1945. Lynch retired from the Navy on 1 December 1950, and died from cardiac failure due to coronary arteriosclerosis, at Oakland, Calif., on 5 October 1970, survived by his wife, Ruth I., and four sons (William A., Jr., Richard B., Jerome, and John) and a daughter (Patricia).

2. Ottley -- born in New York City on 22 April 1903 -- attained the ranks of lieutenant junior grade on 5 December 1940, lieutenant on 15 June 1942, and lieutenant commander on 29 July 1943; Following the war, Ottley was discharged from active duty on 3 March 1946, transferred to the Retired Reserve of the Naval Reserve as a commander on 1 November 1953, and died—while not serving on active duty—on 30 April 1966.