Drum (SS-228)

1941–1968

A bottom-dwelling fish of the family Sciaenidae, known for making a drumming or croaking noise by using muscles associated with its air bladder.

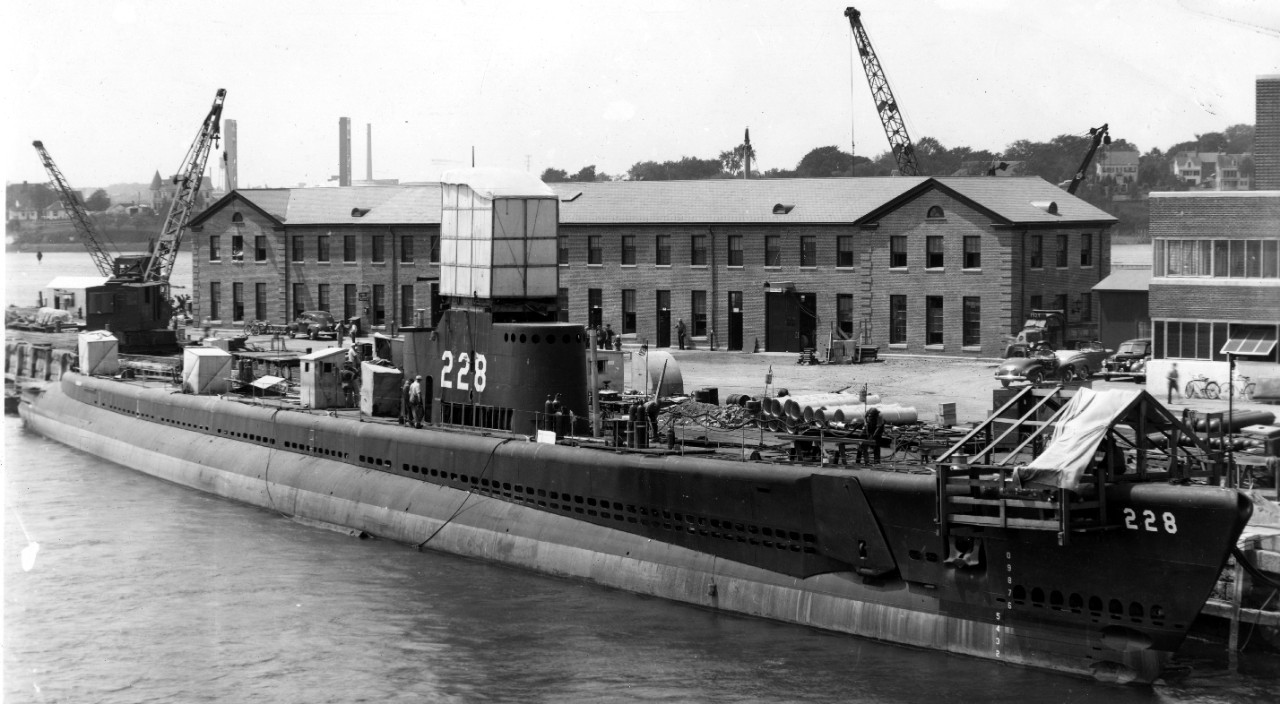

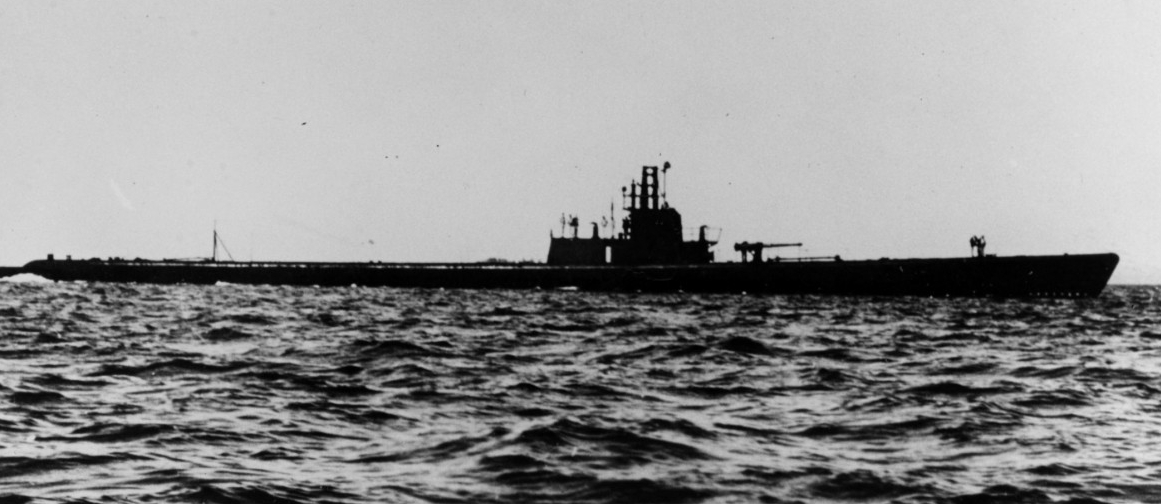

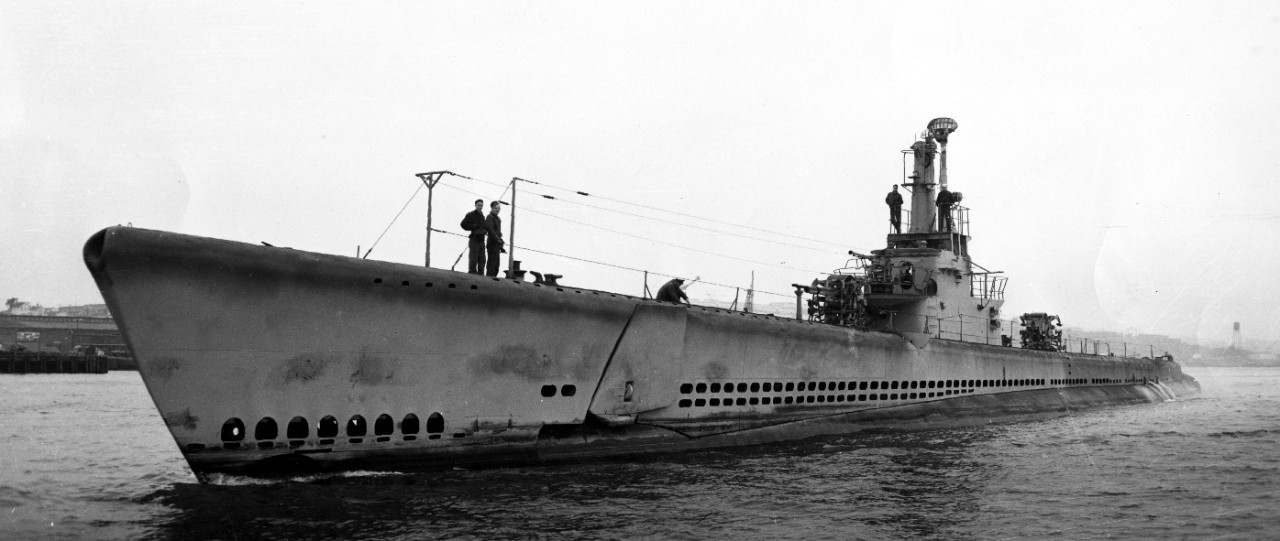

(SS-228: displacement 1,526 (surface); length 311'8"; beam 27'4"; draft 15'3"; speed 20 knots (surface); complement 60; armament 1 3-inch, 2 .50 caliber machine guns, 2 .30 caliber machine guns, 10 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Gato)

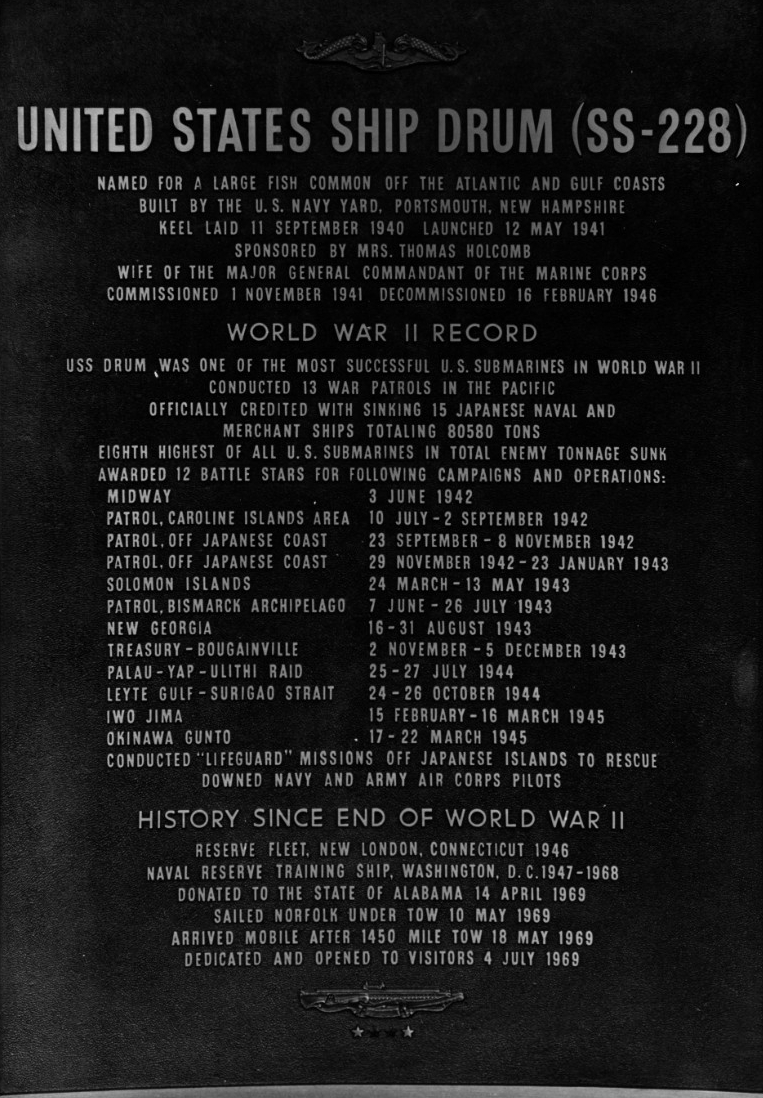

Drum (SS-228) was laid down on 11 September 1940 at Portsmouth [N.H.] Navy Yard, N. H.; launched on 12 May 1941; and sponsored by Mrs. Beatrice M. [Clover] Holcomb, the wife of Maj. Gen. Thomas Holcomb, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps and daughter of Rear Adm. Richardson Clover (Ret.).

Commissioned at her building yard on 1 November 1941, Lt. Cmdr. Robert H. “Bob” Rice (USNA 1927), in command, Drum conducted her shakedown between 1 November and 7 December 1941, during which she trained and ran trials out of New London, Conn., Key West, Fla., and Balboa, C.Z. Following the devastating Japanese surprise attack on U.S. naval and military forces on Oahu on 7 December 1941, Drum immediately underwent voyage repairs and completed additional training in anticipation of a deployment to the Pacific.

She proceeded to Pearl Harbor, arriving there on 1 April 1942, to be immediately entrusted with a mission of the utmost emergency. Shortly after her arrival, Drum received an order to take “certain critical stores from Pearl Harbor to Corregidor Island and conduct offensive patrol in area eleven.” Dutifully, she took on her “critical stores,” that consisted of Army medical supplies and some “foul smelling vitamin pills” and shipped out. Her mission, in addition to the delivery of the stores, also directed her to assist the recently commissioned cargo ship Thomas Jefferson in running the Japanese blockade.

On 6 April 1942, Drum departed Pearl and set a course for the first stop of her mission, Midway atoll, located near the western end of the Hawaiian archipelago. At midday, Drum arrived at Midway and moored. The recent surrender of U.S. forces in Bataan, however, resulted in the mission being scrapped and only a few hours after arrival she received orders to return to Pearl. On 14 April, the submarine reached Oahu and made contact with her escort Litchfield (DD-336) and proceeded in company to Pearl.

Once moored, Drum offloaded her special stores, topped off her fuel bunkers, and took on a full allowance of torpedoes in preparation for her first war patrol that began on 17 April 1942 when she cleared Pearl and set course for the west coast of Japan in the vicinity of Nagoya. In the days immediately following her departure, the boat conducted ship and fire control drills, as well as several training dives. She moored and refueled at Midway on 21 April, then continued on her way that same day. On 25 April, approximately 500 miles north of Wake Island, Drum made her first recorded contact with Japanese forces when radar detected an object, later identified as a large aircraft, which closed to within two miles of her. Before the plane sighted her, the ship conducted her first emergency dive.

On 1 May 1942, Drum arrived at her assigned station. In the early morning hours of 2 May, she initiated her first direct attack on enemy forces. Having sighted Mizuho (Capt. Okuma Yuzuru, commanding) a 9,000-ton Japanese seaplane tender, Drum swung to port in order to close and attack. She fired two torpedoes at a range of 1,000 yards, at least one of which was believed to have made contact. Confirmation of the hit was based on an audible explosion heard roughly 35 seconds after the launch. Following the firing of the second torpedo an enemy destroyer appeared and began closing fast. Drum turned to starboard and dove. In so doing, she avoided a potential ramming and managed to simultaneously fire a torpedo at the oncoming destroyer a shot which failed to hit. The boat remained submerged for 22 hours while the enemy hunted for her and dropped numerous depth charges, her adversaries eventually giving up pursuit. At the close of her first engagement, the submarine surfaced, recharged her batteries and gave her crew some much needed rest. Mizuho, despite energetic damage control efforts, was abandoned shortly after the end of the mid watch the following morning, with the loss of 7 officers and 94 men.

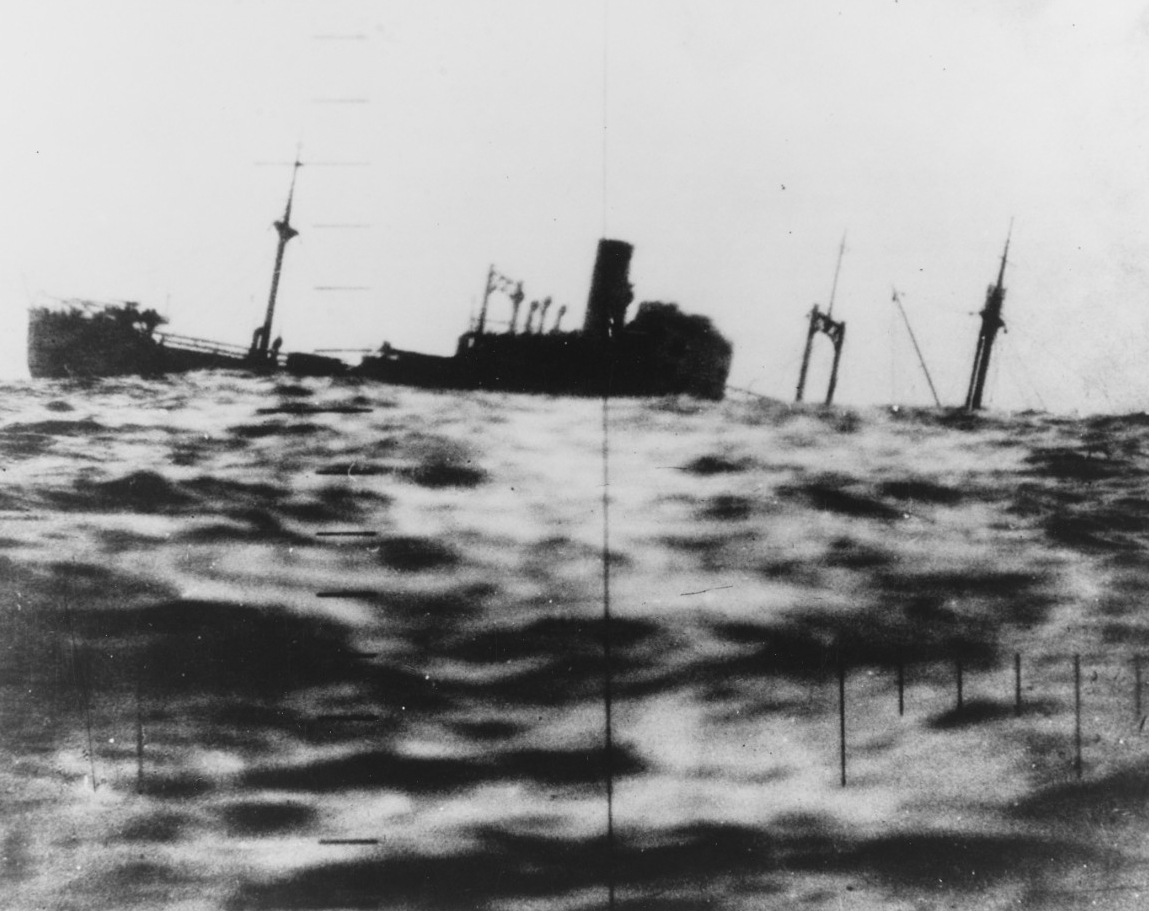

While patrolling off Kantori Zaki on 9 May 1942, Drum encountered a 6,000-ton Japanese cargo vessel near 33°48'N, 136°08'E. She fired four torpedoes, one of which managed to sink the enemy vessel. Only a few days later on 13 May, while submerged off the coast of Tsumeki Saki, Drum sighted smoke from the 6,000-ton Japanese cargo steamer Shonan Maru. The submarine fired one torpedo from her bow tubes and hit the steamer directly amidships, splitting her in half. Drum struck again on 25 May, near 34°58'N, 140°04'E, where she sank the 3,000-ton Japanese cargo vessel Kitakata Maru, and again used only one torpedo to do the job.

The sinking of Kitakata Maru capped off Drum’s first war patrol. After 56 days at sea, 36 of which were spent on station, she arrived back at Pearl on 12 June 1942, for refitting and training. In total, she sank four enemy vessels consisting of 24,000 tons, as well as gathered intelligence on Japanese coastal defense protocols and antisubmarine warfare practices. Overall, the operation was deemed a success and the crew received the honor of wearing the submarine Combat Insignia Award.

Re-fitted and her crew rested, she began her second war patrol on 10 July 1942. She departed Pearl and set a course for her assigned station between the islands of Turk, the Carolines, and New Ireland. Only a few days into her voyage, on 12 July, Drum received orders from Commander Task Force (CTF) 7 to investigate a Japanese ship possibly aground in the area of the Rongelap atoll. She increased speed to full on two engines and arrived approximately 25 miles off the northern edge of Rongelap on the morning of 18 July. Upon her arrival, Drum submerged and after making landfall reconnoitered the area. While doing so, she sighted the masts of a grounded vessel but upon further inspection, Bob Rice decided that the situation did not present a promising opportunity. On 19 July, the boat continued on to her assigned area.

Drum entered her designated patrol zone on 24 July 1942. The patrol was certainly not without its excitement but in the end, she sank no enemy ships. Despite that fact she did, during the intervening weeks, come into close contact with the enemy numerous times but unfortunately found her efforts consistently hindered, either by unfavorable circumstances or the poor performance of her Mk. 15 torpedoes. Her closest scrape with the enemy occurred on the morning of 6 August, when she sighted an enemy cargo ship. The crew manned their battle stations and she approached the Japanese vessel in preparation for an attack. Confident of her position the submarine fired three Mk. 15 torpedoes from her stern tubes; at least one of the torpedoes was a confirmed hit but no positive evidence of damage was detected. As Drum attempted to observe the enemy a bomb splashed only a short distance from her periscope. The submarine dove rapidly.

Drum remained submerged for some time, running silently and listening carefully to the distant sounds of depth charges above. Whatever, damage she had done to the enemy she could not account for it and the attack was the closest she came during that patrol to sinking an enemy vessel. Indeed, Drum also encountered two enemy destroyers on 20 and 21 August 1942, but was unable to reach a favorable firing position. With her arrival at Midway on 2 September, she ended her second war patrol at Midway. Although the 52-day [patrol] was deemed unsuccessful she gathered intelligence and her crew emerged no more the worse for wear upon arrival.

Following a refit at Midway, Drum again put her out to sea on 23 September 1942, for her third war patrol. Bound for the eastern coast of Kyūshu, Drum conducted ship, gun, and fire control drills en route. While submerged approximately four miles off Kiki Saki on 8 October, Drum sighted smoke. A tense 15 minutes passed until at last she sighted an enemy convoy of four freighters with air cover. Once in position she immediately fired two torpedoes but both missed. She let loose another salvo aimed at a second ship and scored at least one hit. In another moment, she had fired again at the third ship but neither torpedo made their mark. Initial observations confirmed that the second ship a 5,339-ton passenger-cargo vessel Hauge Maru, was dead in the water and set ablaze near 34°06'N, 136°22'E. The time taken for observation of the action was fraught with risk, as Japanese planes had been dropping bombs in Drum’s vicinity since the conclusion of her last salvo. Thus engaged, Drum made a quick departure.

On 9 October 1942, Drum encountered Yawatasan Maru, a 7,000-ton Japanese freighter, off southern Honshu and fired three torpedoes. The first exploded prematurely and the second missed. In the intervening time, Yawatasan Maru had time to open fire on Drum, but the third torpedo made a direct hit and the vessel sank in a matter of minutes. Before the end of the patrol, Drum executed one more successful strike against the Empire in the late afternoon of 20 October, when she engaged and sank the 7,200 ton Japanese cargo vessel Ryunan Maru of southern Honshu and damaged one other 6,700-ton Japanese freighter near 34°08'N, 136°46'E.

Drum stood in to Pearl Harbor on 8 November 1942, and thus ended her third war patrol. During her 46 days, of which 29 were spent on station, she sank 19,539 tons of enemy shipping and damaged 6,700 tons more. Drum and her crew remained in good shape, and in return for their valiant efforts they received a battle star.

Lt. Cdr. Bob Rice was relieved by Lt. Cmdr. Bernard F. “Mac” McMahon (USNA 1931) on 14 November 1942. During her time in port, Drum was also refitted and had an SJ radar installed. After only a few weeks of rest and with a new commanding officer, Drum set out for her fourth war patrol on 29 November. Her mission this time was not as straightforward as it had been in the past, as she was tasked with the responsibility of mining the Bungo Suido, a heavily traveled channel between the Japanese islands of Kyushu and Shikoku.

Before reaching her operating area, however, Drum encountered the 7,600 ton Japanese carrier Ryūhō (Capt. Soma Nobishiro), that had recently completed conversion from the submarine depot ship Taigei (and whose construction had been interrupted by the Halsey-Doolittle Raid of 18 April 1942). On 12 December 1942, she detected a plane on her radar and quickly submerged. A short time later, she cautiously surfaced and scouted the area. After investigation, she sighted the carrier Ryūhō, which contained a deck load of 20 planes, and was being escorted by the destroyer Tokitsukaze. Drum lay in wait, allowing the enemy escort to pass and then at high speed fired four torpedoes at Ryūhō. Reverberating explosions could be heard and when she at last raised the periscope she saw the “carrier listing to starboard and down by the bow.” Ryūhō listed to the point that her entire flight deck became visible. Ryūhō then fired her guns on Drum’s exposed periscope, but to no effect. The destroyer escorting the carrier was still in close proximity and was moving close abroad. Drum took immediate evasive action and initially dove to 200 feet, her port shaft going out of commission as the depth charges began exploding around her, some directly overhead. Nonetheless, the boat managed to escape unscathed; Ryūhō made it to Yokosuka with moderate damage; Drum had kept her out of business until early February of 1943.

Drum continued on patrol and on 16 December 1942, arrived in her operating area—the Bungo Suido. Once on station she encountered numerous patrol boats which initially hindered her mining activities as she endeavored to keep her distance from them. In one particular instance on 21 December, Drum sighted a Japanese patrol boat approximately 5,000 yards out. The boat attempted to signal and Drum, not recognizing the sign, improvised a response while keeping her distance. Oddly, the patrol boat twice reciprocated Drum’s response and then turned away. Despite numerous such interactions with various patrol boats in the area Drum successfully planted her mines. She also did damage to at least one 8,000-ton tanker and after a total of 56 days on patrol, 29 of them in her assigned area, Drum arrived back in Pearl on 24 January 1943. Successful in her mission and having inflicted a combined total of 15,600 tons of damage upon the enemy, she received another battle star. From the date of her arrival at Pearl through 24 March, the boat underwent a thorough overhaul.

Drum left Pearl on 24 March 1943, and commenced her fifth war patrol, bearing full ahead towards the vicinity of the equator south of Truk [Chuuk] Lagoon. Prior to entering her assigned patrol area Drum conducted photographic reconnaissance of Nauru Island, but observed no military targets. She then carried on to her assigned offensive patrol area. On 9 April, near 00°32'N, 150°05'E, attacking a convoy, she sank the 3,809-ton Japanese army cargo ship Oyama Maru north-northwest of Kavieng, New Ireland. The escort, the submarine chaser Ch-39, responded with depth charges but Drum emerged unharmed from the encounter. The next day, on 10 April, near 01°37'N, 149°20'E, she spotted a column of Japanese cargo ships and fired three torpedoes at them. Her efforts sank the last ship in the column, the 5,000-ton ammunition ship Akagisan Maru.

Later in her final action of the patrol, on 18 April 1943, Drum sank yet one more enemy cargo ship, the 6,380-ton Nisshun Maru, near 1°55'N, 148°24'E. Ch-18 rescued the vessel’s survivors (who included a number of Army prostitutes). In sum, her efforts culminated in the sinking of a total of 15,874 tons of enemy shipping, and earned her another battle star. With her 50-day patrol successfully completed, Drum was ordered to Brisbane, Australia, for refit and recreation—she arrived at that port on 13 May.

Again, ready for the high seas, Drum set out on her sixth war patrol on 7 June 1943, headed towards the northern waters of the Bismarck Archipelago, entering her assigned area on 15 June, and quickly brought the fight to the enemy. On 17 June, in the area of 2°310'N, 153°4410'E, she sighted two Japanese freighters being escorted by a Mutsuki-class destroyer. Battle stations manned, she fired four torpedoes at the enemy column and commenced evasive maneuvers by going deep. At least three of her torpedoes made it to their target but the submarine remained hesitant to leave the protection of the deep, as explosions sounded above her. It was several hours before she was able to resurface and in so doing she saw nothing of her action. U.S. aerial reconnaissance later confirmed she had indeed sunk her target, relieving the Empire of Japan of the 8,666-ton cargo ship Myōko Maru. The victory proved to be her singular success of that particular patrol, which ended with her return to Brisbane on 26 July. In total, she was 49 days at sea and with her efforts deemed a success she earned yet one more battle star for the patrol.

Replenished at port, Drum set out to war a seventh time on 16 August 1943, her destination the seas between the Admiralty Islands and the northern coast of New Guinea. On 27 August, enroute to her assigned patrol zone Drum sighted a convoy but was ultimately unable to engage. Later that same day she encountered a large convoy consisting of five medium freighters and two escorts. Drum conducted a nighttime surface attack and in so doing launched six torpedoes. At least three hits were heard but the extent of the damages inflicted upon the enemy could not be confirmed as the reprisal of the convoy’s escorts forced her to take evasive action.

The most significant action of Drum’s seventh patrol commenced in the early afternoon of 8 September 1943, in the area of 2°44'S, 141°36'E. At 1158, Drum sighted smoke from the 2,900-ton Japanese cargo vessel Hakutetsu Maru. With three torpedoes, she left Hakutetsu Maru in a sinking condition and observed at least 100 of her survivors in rafts. Mac McMahon, Drum’s commanding officer, observed the turmoil on the life rafts and recalled seeing “one irate member of the torpedoed ship’s company kick one of his shipmates over the side of a lifeboat.” The submarine continued to monitor the wreckage and observed the approach of another Japanese freighter, which ultimately declined to aid her stranded companions. The action was concluded without further exploits, and the day ended with all hands partaking in an eight-layer birthday cake served for one of the crew’s officers.

On 23 September 1943, Drum departed her patrol area and put into Tulagi Harbor, in order to repair the submarine’s gyroscope. After completing repairs, she continued on and at last arrived in Brisbane on 6 October. In total, she sank three Japanese vessels, totaling 12,900 tons. Her patrol was deemed a success and the ship received another battle star for actions between 16 and 31 August.

Shortly after her return to Brisbane, Mac McMahon, having taken the boat on five war patrols, turned over command to Lt. Cmdr. Thomas K. Kimmel, who served as commanding officer until relieved by Cmdr. Delbert F. Williamson (USNA 1927), a classmate of her commissioning commanding officer and a man remembered by his classmates at the Academy as “strong, good-natured, and frank.” On 2 November 1943, with “Bill” Williamson at the helm, the submarine set out on her eighth war patrol, setting a course for the area between the Bismarcks and the Caroline Islands and arrived on station on 9 November.

In the early morning hours of 11 November 1943, Drum sighted a Japanese convoy of what appeared to be three large transports and three escorting destroyers. Eager for battle, the crew manned their battle stations and the boat submerged in preparation for an attack, firing a barrage of six torpedoes at an 11,960-ton transport. The attack caught the Japanese convoy completely off guard and at least two of the torpedoes struck home. Keen to avoid retaliatory fire from the escorting destroyers, she dove. Depth charges exploded close aboard, but resulted in no damage. After surfacing, she detected no wreckage or oil and so cleared the area.

On 17 November 1943, in choppy seas in the area of 1°48'N, 148°24'E, Drum executed a successful attack against the 4,700-ton Japanese submarine depot ship Hie Maru – the vessel that had eluded her on the 11th – and, this time, sent her to the bottom. Drum followed up the exploit with another assault on the enemy on 22 November. Unfortunately, the attack proved to be more costly than beneficial. Having sighted smoke from three ships, at least two of which proved to be Japanese patrol boats. Drum fired four torpedoes and then immediately dove. In close pursuit, the enemy delivered a series of punishing depth charge attacks which eventually led to a “clean crack” in the plating of the boat’s conning tower. Drum survived, but received orders to return to Pearl, where she arrived on the morning of 5 December. From Pearl, she was then sent to the Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif., on the west coast of the U.S., to receive a new conning tower and undergo a thorough overhaul. The ship’s eighth patrol was deemed a success and her crew awarded a battle star for her actions between 2 November and 5 December.

A few months after undergoing repairs, Drum returned to the Pacific theatre and arrived at Pearl on 29 March 1944. On 9 April, the boat departed on her ninth war patrol with a course set for the Bonin Islands including Iwo Jima, Hara Jima, and Chichi Jima. Shortly after her departure Drum’s crew located a twelve-inch crack in a metal plate located in the hull of the engine room. On 11 April, she moored at Johnston Island in order to repair the damaged hull. She put back out to sea on 12 April and continued on to her assignment.

After arriving on station on 22 April 1944, Drum encountered numerous Japanese planes but ultimately engaged no enemy ships. In fact, she fired no torpedoes and did no physical damage to the enemy whatsoever; a circumstance which was notably distressing to her crew, many of whom were ‘green’ and wanted experience. Nonetheless, the boat diligently patrolled her assigned waters and carried out a valuable reconnaissance mission of Chichi Jima, which aided U.S. surface ships in its bombing. After 31 days on station, she charted a course for the Majuro Atoll in the Marshall Islands. She reached Majuro on 31 May, concluding her patrol, which although true in spirit was deemed as “not successful” for the award of the submarine Combat Insignia. Once at port, Drum required a two-week refit period to fix ongoing mechanical issues.

On 14 June 1944, shortly after Drum arrived at Majuro, command again changed hands, with Lt. Cmdr. Maurice H. “Mike” Rindskopf (USNA 1938), a plank owner, taking charge. On 24 June, Drum set out on her tenth war patrol, bound for the Palaus, and charged with the primary mission of lifeguard duty for USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberators flying over Yap Island; as well as a raid conducted between 26-27 July by the fast carrier task force (TF 58) under Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher. On 3 July, while on a surface patrol south of Yap, Drum had a close scrape with several Japanese planes that managed to machine gun her wooden deck but caused no appreciable damage to the durable Portsmouth Navy Yard boat.

On 4 July 1944, Mike Rindskopf decided to “include Japanese forces on Fais Island in her celebration of American Independence.” At approximately 2130, Drum began a bombardment of the island. Having surfaced off the coast of Refinery Point, Drum manned her battle stations, closed on the enemy outpost and with her .50 cal. machine guns opened fire at 4,000 yards. At 1,500 yards, she added her 20 millimeter and .30 caliber machine guns to the assault. The submarine ceased fire at 2240 and although she unable to determine the extent of the damage inflicted, Drum left the enemy in a bad state, for as she departed, she jammed several frantic radio calls being sent out by surviving Japanese forces.

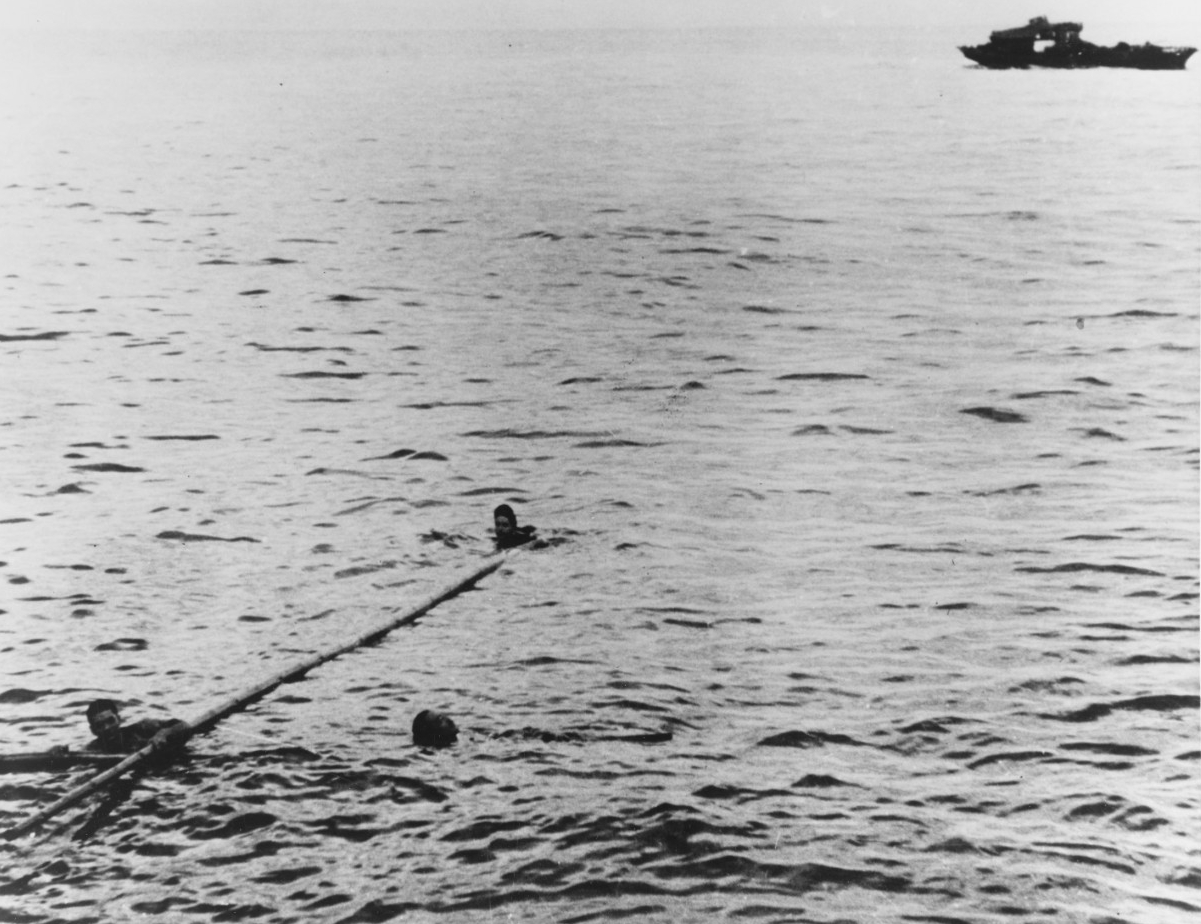

From 26-27 July 1944, Drum observed and supported a U.S. raid, but her primary action of the patrol occurred on 29 July, when she spotted two unarmed sampans. She surfaced to engage them with all guns. With the 25-ton sampan ablaze, she observed numerous survivors in the water. Drum approached the remaining men, only two of whom could be coaxed on board to be taken prisoner. On 10 August, the ship departed her patrol area and set a course for Pearl where she arrived on the 14th. Drum completed a successful 51-day patrol, with 31 days spent in her assigned area. For her efforts during the patrol the crew was granted the submarine Combat Insignia Award.

On 9 September 1944, Drum departed Pearl for her eleventh war patrol in a coordinated attack group or “wolf pack,” which included Sawfish (SS-276), Icefish (SS-367), and Rock (SS-274). Cmdr. Alan B. Banister, Sawfish’s captain, led the wolf pack. At 1900, Rock and her escort parted company, and Drum continued to Saipan with Sawfish and Icefish. On 24 September, Drum was ordered to set course for Surigao Strait. From 28 September to 13 October, she made no aircraft or ship contacts. On 14 October, in support of a move by the carrier task force that conducted landings on Leyte, Drum set course for the Luzon Straits, or as it was also known “Convoy College.” On that same day, the crew was planning to celebrate her 1,000th dive when they were sighted by an enemy aircraft and had to take evasive maneuvers.

Drum reached her assigned area on 16 October 1944, and commenced scouting the Luzon Straits area of the South China Sea. On 18 October, Drum while continuing her patrol of the area, formed a wolf pack with Sawfish and Icefish. On 22 October, Drum located an Asashio-class destroyer but was unable to take a shot at her, which greatly frustrated the crew. The next day, she encountered a convoy of four enemy ships with at least three escorts. One of the latter closed in on Drum, who prepared to attack. However, astoundingly, even at 2,700 yards the enemy proved apparently still unable to locate Drum who initiated her own attack from the port flank by firing four torpedoes—none of which found their mark. Snook (SS-279), which was also involved in the action managed to hit the convoy with at least two torpedoes. Meanwhile, Drum assumed a ready but cautious posture as she was being surrounded on three sides by the convoy’s escorts, preventing her from launching an attack and the arrival of a fourth enemy ship threatened to box her in completely, so endeavoring to live to fight another day she evaded the enemy.

Drum outpaced her pursuers and a short time after doing so she happened upon yet another enemy freighter, the 6,700-ton Shikisan Maru in the area of 20°27'N, 118°31'E. The enemy freighter was also in company with an Asashio destroyer. Eager to make the day a success, Drum engaged Shikisan Maru and struck her with two torpedoes. Drum observed an additional freighter as well but could not attain an appropriate attack position. Meanwhile the former ship’s escort was closing on Drum, which initiated timely evasive maneuvers, as shortly thereafter 13 depth charges exploded in her immediate vicinity.

Drum sighted another large enemy convoy, MOMA-05 on 26 October 1944, consisting of ten freighters and three escorts, off the northwestern coast of Luzon. She closed in and with “an escort dead ahead,” commenced firing. The failure of the convoy’s escorts to notice her at the outset allowed her to launch a second foray. In the area of 19°21'N, 120°50'E, she sank the 7,500-ton freighter Taisho Maru, the 6,900-ton cargo vessel Taihaku Maru, and damaged two transports, Aoki Maru and Tatsura Maru. Her initial spread was enormously successful but the convoy’s escorts finally managed to position themselves between Drum and the remaining cargo ships in order to thwart any additional assaults. Unable to reengage she eventually broke off the attack. After she left her patrol area, the submarine spent three days conducting lifeguard duty, searching for downed aviators in the Luzon Strait—without success. Despite such disappointments, she could take solace in the knowledge that the convoy she attacked was being sent to reinforce Japanese forces during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which took place between 23 and 26 October.

On 8 November 1944, Drum stood in to Majuro, thus ending her eleventh war patrol. In total, she sank 25,100 tons of enemy shipping and was deemed successful in her undertakings against the enemy. For her exploits between 24 and 26 October, she was also awarded a battle star. On the same day as her arrival to port, Drum’s captain was relieved by Lt. Cmdr. Frank M. Eddy, who, one classmate (USNA 1937) described as having a “modest, easy-going disposition with a philosophic outlook on life.”

For all her many incursions in the war, Drum’s twelfth war patrol proved substantially less eventful than many of her others. She departed Majuro on 7 December 1944, in company with the veteran Sargo (SS-188), and arrived alone in her assigned area around Nansei Shoto. She engaged the enemy only once during the course of the patrol, when on 30 December, she encountered a large convoy with several escorts. With good visibility but choppy seas, Drum positioned herself to fire on the largest ship of the lot. At a range of 2,000 yards she fired a spread of six torpedoes from her bow tubes, but to no avail. An aggressive enemy escort gave Drum no choice but to dive and evade. It was the singular direct action of her patrol. After 41 days at sea, with 25 of them spent on station, Drum ended her twelfth patrol on 17 January 1945, with her arrival at Apra Harbor, Guam. During her stay she was drydocked for bottom work and sea valve repair.

On 11 February 1945, Drum cleared Guam on her thirteenth war patrol and set a course toward Nansei Shoto and Nanpo Shoto. She originally departed in the company of Piranha (SS-389), Puffer (SS-268), Sea Owl (SS-405), and escort craft Roe (DD-418). She arrived in the Nansei Shoto on 16 February and later, from 13 to 22 March, patrolled Nanpo Shoto. In addition to her patrolling, Drum provided lifeguard services for a carrier strike on Okinawa and for USAAF Boeing B-29 Superfortress raids at Honshu on the Japanese mainland. During her lifeguard duties she searched for several downed U.S. aviators but located none. Indeed, after 50 days on patrol she not only conducted no rescues but was unable to locate any viable enemy targets because of the dwindling Japanese merchant marine.

However, not all of a war patrol’s issues can be counted in rescues lacking or targets undeveloped. Early in the voyage the crew experienced several cases of food poisoning, believed to be the result of some poorly packed orange juice produced by K&R Fruit Products. If as the proverb goes ‘armies march on their stomachs,’ then surely sailors sail on them. As such, issues with regard to the submariners’ food supply and food quality tend to be no small matters. In the ship’s war patrol report her commanding officer not only lamented the quality of the food but also the skill of the cooks. As the logs, memorably recounted “The performance of the cooks was not up to par. They are in a rut. Cooks are born and not made.” Issues of food aside—although the patrol was technically deemed “unsuccessful” Drum earned a battle star for the patrol, which ended with her arrival at Pearl on 2 April 1945. From there she traveled to Hunters Point, Cal., for drydocking, after which she then departed Hunters Point and between 25 July and 9 August, underwent repairs and conducted training out of Midway.

An intrepid but certainly war weary Drum departed from Midway on 9 August 1945, for what would have been her fourteenth war patrol. However, shortly after she set out, on 14 August, Drum received a typed radio message notifying the crew of Japan’s surrender. After Drum received the notification she was sent to Saipan, arriving there on 18 August and was very soon thereafter ordered to Pearl, where she arrived on 29 August. Drum briefly took on fuel and then set out from Pearl on 31 August. She arrived at Balboa, C.Z. on 17 September. Then, at long last, after four years at war, Drum arrived back at her home station Portsmouth, on 15 September 1945.

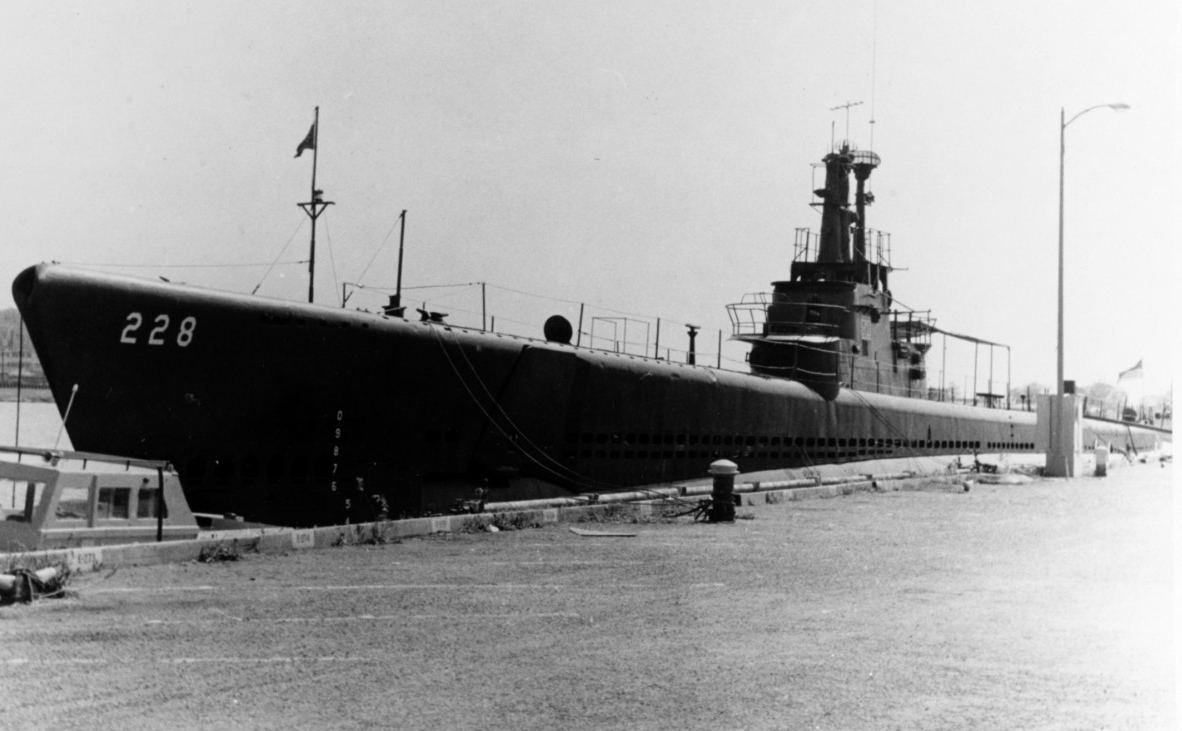

Drum was decommissioned on 16 February 1946, at New London, Conn., and a little over a year later, on 18 March 1947, was turned over to the District of Columbia’s Naval Reserve program and moored to a pier alongside the Naval Gun Factory [the current Washington Navy Yard]. There she was used for training in the Potomac River Naval Command until 6 November 1962, when she was reclassified as an auxiliary submarine AGSS-288.

Stricken from the Naval Vessel Register on 30 June 1968, the boat was donated on 14 April 1969 to the USS Alabama Battleship Commission. She is currently at Battleship Park in Mobile, Alabama. She is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and was designated a National Historic Landmark on 14 January 1986.

Drum received twelve battle stars for her World War II service. She put out to sea 13 times to conduct war patrols against the Empire of Japan and received credit for sinking15 enemy ships totaling 80,580 tons. Her legacy in numbers is impressive but such statistics are ultimately no more than a reflection of the tireless and valiant efforts of her sailors, volunteers all, who braved not only the ocean’s depths but fought a tenacious foe.

| Commanding Officers | Date Assumed Command |

| Lt. Cmdr. Robert H. Rice | 1 November 1941 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Bernard F. McMahon | 14 November 1942 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Thomas E. Kimmel | 7 October 1943 |

| Cmdr. Delbert F. Williamson | 18 October 1943 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Maurice H. Rindskopf | 24 June 1944 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Frank M. Eddy | 15 November 1944 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Horace P. McNeal | 4 January 1946 |

Jeremiah D. Foster

9 February 2018