Cleveland II (CL-55)

1942–1959

A city in Ohio.

(CL-55: displacement 10,000 tons; length 610'1"; beam 66'6”; draft 20'; speed 33 knots; complement 992; armament 12 6-inch, 12 5-inch, 8 40-millimeter, 15 20-millimeter; class Cleveland)

The second Cleveland (CL-55) was laid down on 1 July 1940 at Camden, N.J., by the New York Shipbuilding Corp.; launched on 1 November 1941; sponsored by Mrs. Selma Florence Smith Burton, wife of Senator Harold H. Burton (former three-term mayor of Cleveland, Oh.); and commissioned at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pa. on 15 June 1942, Capt. Edmund W. Burrough in command.

Cleveland fitted out and conducted her shakedown in the Chesapeake Bay through 15 September 1942. Adm. Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), made the ship available for testing prototype Mk. 32 5-inch/38 anti-aircraft projectiles with radar-enabled proximity fuses, technology under secret development at The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in nearby Baltimore, Md. Cmdr. William S. “Deke” Parsons, coordinating the effort for the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance, oversaw the tests. Cleveland required fewer than 10 Mk. 32 rounds to splash two radio-controlled drones simulating torpedo attacks over the Chesapeake on 12 August. She quickly shot down another drone flying a mock high-altitude bombing run the next morning. The successful tests enabled full-scale production of Mk. 32 ammunition to begin in September and initial delivery to the fleet in November.

Propulsion system difficulties required Cleveland to put into Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., for “urgent and necessary” post-shakedown repairs (28 September–2 October) before joining the fleet. Following maintenance, Adm. Royal E. Ingersoll, Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANT), allocated Cleveland to Operation Torch, the combined U.S.-British invasion of Vichy French North Africa, scheduled to begin in early November. He assigned her to Task Group (TG) 34.2, Center Air Group, under the command of Rear Adm. Ernest D. McWhorter. Its mission was to provide air support for joint amphibious landing operations with U.S. Army troops against Vichy forces defending Fedhala, French Morocco [Mohammedia, Morocco]. Cleveland joined Task Unit (TU) 34.2.1, also commanded by McWhorter, which included aircraft carrier Ranger (CV-4), auxiliary carrier Suwanee (ACV-27), and five destroyers.

Clearing Naval Operating Base, Norfolk, Va., on 10 October 1942 with McWhorter and his staff embarked, Cleveland sailed for the Bermuda Islands to join the rest of TG 34.2, escorted by destroyer Hobson (DD-464). Cleveland and Hobson zigzagged during periods of clear visibility to thwart potential enemy submarine attacks. Upon anchoring in Great Sound, Bermuda, on 12 October, McWhorter shifted his flag to Ranger. Based on recent battle experience from the Pacific theater, Cleveland’s bluejackets prepared their ship for wartime combat conditions by stripping all non-essential flammables including linoleum, furniture, and paint, to minimize fire hazards. On 21 October, Center Air Group conducted its only dress rehearsal for Torch while Cleveland stood out for independent anti-aircraft exercises.

Center Air Group sailed on 25 October 1942 to rendezvous with Task Force (TF) 34, Western Attack Force (Rear Adm. H. Kent Hewitt), in the mid-Atlantic on 28 October. Cleveland and Ranger alternated as formation guides for Center Air Group, which took station about five to ten miles behind TF 34’s main body, steaming on southeasterly courses for Africa. Cleveland’s detachment of Curtiss SO3C Seamew scout observation seaplanes from VCS (Cruiser Scouting Squadron) 12 participated in the group’s daylight anti-submarine patrols. At night, her communications department monitored repeated medium frequency homing transmissions from suspected German Navy submarines along the Western Attack Force’s intended course. Cleveland’s radiomen also discovered enemy radio stations doing direction finding of their own, critical intelligence passed directly to Rear Adm. McWhorter. Western Attack Force closed on the coast of French Morocco on 7 November, and despite conflicting weather forecasts, Hewitt ordered Torch to begin the next day. Center Air Group shaped course during the afternoon watch for its assigned operations area, 30-50 miles west of Casablanca, French Morocco [Morocco].

Cleveland screened Ranger and Suwanee as they launched aircraft in moderate weather at 0615 on D-Day, 8 November 1942. Ten minutes later, Hewitt signaled “Play Ball,” and Ranger’s planes commenced their planned attacks in support of the Center Attack Group’s landings. Cleveland’s floatplanes flew continuous anti-submarine patrols while she kept formation with Ranger throughout the next two days. She sighted no enemy forces, recording both days as “uneventful” in her war diary. This changed on the morning of 10 October. At 0900, lookouts sighted two torpedoes closing broad on the port bow. The French Navy submarine Le Tonnant, which had escaped Casablanca harbor on 8 November, likely fired them. With Cleveland swinging to starboard as she followed Ranger into a turn, Capt. Burrough made the split-second decision to parallel the incoming projectiles rather than comb them head on. He ordered hard right rudder and all engines ahead emergency. As the ship heeled, Burrough backed the starboard engine full, completing the turn. Spotters then found two more torpedoes to the left of the initial pair. One missed ahead by 500 yards while a second just cleared the bow and the third sliced by astern. As the fourth approached, Cmdr. Charles B. McVay III, executive officer, remarked, “That one can’t possibly miss us, Captain.” The torpedo instead passed under the ship aft of the seaplane hangar without detonating. Corry attacked Le Tonnant with depth charges but the submarine managed to creep away to safety. Being a superstitious lot, Cleveland’s sailors took their seemingly miraculous escape as foretelling a charmed existence for their ship.

Hewitt directed Cleveland to join battleship New York (BB-34) and heavy cruiser Augusta (CA-31) to provide gunfire support for a ground assault on Casablanca scheduled for 0730 on 11 November 1942. Cleveland reached Center Attack Group during the afternoon watch and patrolled outside Fedhala through the next morning. As she steamed into firing position with the bombardment force, Hewitt ordered a cease-fire upon word that Vichy forces were negotiating surrender. Cleveland returned to Fedhala anchorage instead and at dawn the next day she sailed to rejoin Center Air Group, not yet having fired a shot in combat.

Hewitt released McWhorter’s task group from the operation on 14 November 1942. While steaming back to Bermuda in company with TG 34.2, Cleveland received orders assigning her availability in Norfolk Navy Yard. Anchoring overnight in Great Bay, Bermuda on 21-22 November, she proceeded onward, reaching Norfolk on 24 November. Cleveland then immediately entered drydock for emergency alterations to prepare her for service in the Pacific theater. The ship’s company received 72 hours liberty ashore.

With work completed on 5 December 1942, Cleveland stood out in company with a task force under the command of Rear Adm. Robert C. Giffen, bound for the Pacific via the Panama Canal. She and her consorts anchored in Nouméa, New Caledonia Island, on 4 January 1943 before moving to their operational base in Havannah Harbor, Efate Island, New Hebrides [Republic of Vanuatu] on 15 January. There, Cleveland joined sister ships Columbia (CL-56) and Montpelier (CL-57) in the newly formed Cruiser Division (CruDiv) 12, under the command of Capt. Aaron S. Merrill. CruDiv 12 formed TU 18.1.2 within TF 18, under Giffen’s command, which also included heavy cruisers Wichita (CA-45), Chicago (CA-29), and Louisville (CA-28), auxiliary carriers Suwanee and Chenango (ACV-28), and eight destroyers.

Cleveland’s arrival in the South Pacific coincided with the end of the long, costly campaign to retake Guadalcanal Island, Solomon Islands, from Japanese control. In January 1943, Adm. Yamamoto Isoruku, commanding the Imperial Japanese Navy’s Combined Fleet, bolstered air and naval forces in the area to execute Operation Ke, the evacuation of Guadalcanal. Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr., commanding U.S. South Pacific Force, interpreted Ke as an attempt to reinforce the island and committed most of his ships and planes to prevent it. On 27 January, TF 18 departed Efate to rendezvous with a destroyer squadron for a sweep through the lower Solomons, known as “the Slot,” to cover a transport convoy delivering troops to Guadalcanal. After a patrol plane sighted TF 18 on 29 January, the Japanese redirected submarines to the vicinity of Rennell Island, Solomon Islands, southwest of Guadalcanal. They also scrambled two air groups from Rabaul, New Britain Island, New Guinea [Papua New Guinea], proficient in nighttime torpedo tactics to attack the task force. Chenango and Suwanee, detached in the afternoon to maintain the rendezvous schedule, provided air cover for Giffen’s main body until approaching darkness forced the aviators to return to their carriers.

In twilight about thirty minutes after sunset, TF 18 zigzagged at 24 knots on northwesterly courses 50 miles north of Rennell Island on a smooth sea, under mostly overcast skies with a cloud ceiling of 2,000 feet. Gunfire coming from destroyer Waller (DD-466) and the heavy cruisers, all sailing to starboard, alerted Cleveland at 1925 to 15 incoming Japanese Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 (Betty) land-based attack planes of 705 Kōkūtai. TF 18 had tracked aircraft by radar all day but uncertainty about the identity of the approaching contacts impeded timely preparation for an attack. Cleveland’s startled lookouts spotted an approaching Betty just 1,500 yards on the port quarter. With the ship already at General Quarters, her radar directed 5-inch guns engaged within seconds, followed by her 40-millimeter Bofors and 20-millimeter Oerlikon anti-aircraft batteries. Other ships saw torpedoes launched and some maneuvered individually to evade, but none were hit. The attack lasted only a few minutes. Giffen elected to press on as planned and ordered zigzagging ceased when 16 Mitsubishi G3M3 Type 96 (Nell) land-based attack planes of 701 Kōkūtai commenced another run on TF 18 from the east. Under a backdrop of illumination from Japanese flares, burning downed aircraft, and blinding flashes from the task force’s large caliber anti-aircraft guns, Cleveland’s gunners marked just three more aircraft and they claimed no kills that evening. The Nells torpedoed Chicago twice at 1940, leaving her dead in the water. Detailing Waller to stand by Chicago, Giffen directed the rest of TF 18 to reverse course and cut speed to 15 knots, shaking off the remaining pursuers. The task force extracted a price for the first successful Japanese nighttime aerial torpedo strike of the war by splashing three of the 31 attacking planes.

As Louisville rigged to tow Chicago, Giffen detached Merrill’s cruisers and destroyers Chevalier (DD-451) and Taylor (DD-468) at 2029 to screen TF 18’s northwest flank through the night. Chenango, Suwanee, and Enterprise (CV-6) placed combat air patrols (CAP) over TF 18 at daylight on 30 January 1943. Giffen reformed his force to escort Chicago, now towed by the tug Navajo (AT-64), to Espíritu Santo, New Hebrides [Republic of Vanuatu]. Amid reports of shadowing Japanese snoopers, submarines, and more inbound strike planes, however, Halsey ordered TF 18’s undamaged cruisers to shape course back to Efate instead. Leaving six destroyers to escort Chicago and Navajo, Giffen directed the rest of his force east at 1500. TU 18.1.2 intercepted a radio dispatch two hours later stating Chicago had been sunk and a destroyer damaged by enemy torpedo planes. Burrough’s report of the action briefly recounted factual details; McVay added only “The conduct of the officers and crew left nothing to be desired.”

The Battle of Rennell Island dispirited Cleveland and her consorts but they had little time to reflect upon it because a major combat engagement appeared imminent. TF 18 refueled at Efate on 31 January 1943 and then sailed northward to combine with TF 69 (Vice Adm. Herbert F. Leary, commanding battleships New Mexico (BB-40), Mississippi (BB-41), Colorado (BB-45), Maryland (BB-46), and escorting destroyers) on 4 February to patrol to the north and east of the Santa Cruz Islands, Solomon Islands. As U.S. forces secured Guadalcanal following the Japanese withdrawal, Halsey ordered the task forces back to their bases on 10 February. Determined to build unit cohesiveness, Merrill kept Cleveland and CruDiv 12 at sea for additional exercises before anchoring in Havannah Harbor during the afternoon watch on 14 February. That evening Merrill received notification of his promotion to rear admiral and broke his new flag at Montpelier’s main.

Halsey soon put Cleveland and her sisters to work, constituting them as TF 68 to cover Operation Cleanslate, the occupation of the Russell Islands, Solomon Islands, set for 21 February 1943 by a joint Navy-Marine-Army amphibious force. Joined by the newly arrived Denver (CL-58), CruDiv 12 and four destroyers put out of Havannah Harbor on 19 February to rendezvous with the landing force in Port Purvis Anchorage, Florida Islands [Nggela Islands], Solomon Islands. Merrill continually drilled his ships on radar tracking and gunnery, night fighting, and anti-aircraft protection while patrolling between the Russells and Guadalcanal. TF 68 rejoined Giffen’s TF 18 on 26 February to provide distant cover for Cleanslate between Guadalcanal and Efate. While underway, Cleveland conducted special burst firing tests of Mk. 32 proximity fuse ammunition under the eye of Cmdr. Parsons, embarked to observe its use in combat.

Merrill’s task force returned to Espíritu Santo on 3 March 1943 under Halsey’s orders to prepare for an ambitious night bombardment of Japanese airfields on New Georgia and Kolombangara Islands, Solomon Islands, deep within Japanese-controlled waters. After detailed planning with South Pacific Force staff representatives, Cleveland and TF 68—without Columbia, undergoing engine repairs—departed Espíritu Santo on 4 March. The ships threaded their way up the “Slot” the next day at 26 knots under an air umbrella of search planes, torpedo bombers, anti-submarine patrols, and escorting fighters. During the first dog watch, the cruisers sent all of their seaplanes to Tulagi Island, Solomon Islands, for the night. Four Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina “Black Cat” flying boats took station over TF 68 during the second dog watch to scout and spot for the bombardment. At 2000, four of the task force’s destroyers silently left the formation per plan to strike Munda Point on New Georgia. Shortly before midnight, TF 68 intercepted a radio report from Guadalcanal that a search plane had spotted two Japanese light cruisers or destroyers moving at high speed south from Shortland Island, Solomon Islands three hours previously. Not knowing if his force had been located or if the spotting report was accurate, Merrill continued, assuming the enemy might attempt an ambush.

Cleveland steamed south into Kula Gulf between New Georgia and Kolombangara at 0010 on 6 March 1943 at 20 knots, in column between Montpelier and Denver. Destroyers Waller and Conway (DD-507) led the way while Cony (DD-508) screened the port flank against submarines and light attack craft. The night was cool and calm with visibility impaired only by the moonless darkness, which forced TF 68 to navigate via SG search radar. At 0055, Cleveland’s radar operators identified a surface contact to the southwest at 16,100 yards. Two minutes later this resolved into two separate “pips,” headed north across the bay from TF 68. These were the Japanese destroyers Murasame and Minegumo, returning to base after offloading cargo for the garrison on Kolombangara. Merrill relayed a contact report to his force with instructions to stand by. When the range shrank to 10,000 yards, he gave the order to fire. Montpelier’s batteries opened up at 0101 and Waller loosed a spread of five torpedoes. Cleveland’s starboard 5-inch guns joined in moments later, followed by her main battery. All three cruisers aimed at Murasame, the closer and clearer target on their radar displays. Earlier experience with American ships bearing rapid firing 6-inch guns led the Japanese to refer to them as “machine gun cruisers.” In just seven minutes, Cleveland alone fired 120 6-inch and 60 5-inch rounds. A torrent of shellfire engulfed Murasame in splashes and the sixth salvo delivered the first hit. Taken by surprise, the Japanese returned fire slowly in a ragged and inaccurate fashion that failed to strike any targets. Cleveland’s lookouts observed a fire start in Murasame’s after gun mount which suddenly blossomed into an explosion—possibly due to one of Waller’s torpedoes—that threw flame 150 feet into the air. Her batteries shifted to rake Minegumo with 28 5-inch and 47 6-inch shells in three minutes before Burrough ceased firing. Minegumo sailed on for four miles before coming to a stop. Sent to finish the enemy ships off, Waller reported that both had foundered; 176 survivors swam to Kolombangara the next morning.

Knowing that he had lost the element of surprise, Merrill ordered the southern end of Kula Gulf illuminated with starshells to make sure no other enemy ships lurked in the darkness. Finding nothing, the formation proceeded onto a course due north and slowed to 15 knots. The bombardment began at 0127 and Cleveland fired a two-round ranging salvo before delivering the weight of her main and port-side secondary batteries continuously onto pre-set targets at Vila airfield and adjacent bivouac areas. Japanese coastal guns straddled her with three or four shots before the 5-inch guns of the cruisers and destroyers silenced them. Capt. Burrough thought the barrage was “not spectacular,” though Cleveland’s Black Cat spotter saw an ammunition dump burning and several guns knocked out. Another aerial observer deemed it “highly devastating.” Cleveland ceased firing after 11 minutes, having dispensed an astonishing 628 5-inch and 618 6-inch shells.

Untouched by enemy fire, TF 68 increased speed to 30 knots and retired north back through Kula Gulf. The cruisers observed flares behind them of the type that had preceded the night torpedo attack at Rennell Island but no aircraft appeared on radar. The destroyer detachment, which had successfully worked over Munda airfield, rejoined TF 68 shortly before it anchored in Point Purvis during forenoon watch on 6 March 1943. Still thinking his ships had engaged a heavier force, an elated Merrill reported to Halsey, “Sank two light cruisers. What is the 1943 bag limit on those bastards? Bombardment completed.” (This engagement had no official name, but came to be known informally as of the Battle of Blackett Strait.) Of his ship’s performance, Burrough reported, “This initial night surface engagement provided a needed test of unseasoned personnel and material. It was gratifying to have each officer, man and instrument function more effectively than during exercises and target practices.” Burrough received the Legion of Merit, with Combat “V,” for exceptionally meritorious service for the action on 5-6 March, and for his conduct during the Battle of Rennell Island. Cmdr. McVay was awarded a Silver Star for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity.

Following the occupation of the Russells, Halsey’s command (now designated Third Fleet) temporarily paused offensive operations. From early March through late June 1943, Cleveland and CruDiv 12 alternated between routine drills and upkeep at anchor in Havannah Harbor and brief patrols and more exercises at sea. Merrill’s cruisers held high speed maneuvering and anti-aircraft tracking exercises for a day in March with 60 planes practicing attack runs out of Espíritu Santo. They briefly served in the screens of aircraft carriers Enterprise in April and Saratoga (CV-3) in May. By June, Halsey was ready to undertake the next phase of Operation Cartwheel, the campaign plan developed by General Douglas MacArthur, commanding Southwest Pacific Area, to seize the strategically located Bismarck Archipelago. While MacArthur’s forces reconquered mainland New Guinea, the Third Fleet would advance up the Solomon Islands chain, aiming to meet at Rabaul, the main Japanese air and naval base in the south Pacific.

Halsey instructed Merrill to conduct a diversionary raid in support of Operation Toenails, the invasion of New Georgia Island, Solomon Islands, scheduled for 30 June 1943. Capt. Andrew G. Shepard relieved Burrough as Cleveland’s commanding officer on 19 June. He had only a few days to get to know his new ship and its company before he led them into action. During the forenoon watch on 27 June, Merrill’s force, designated TG 36.2 (Cleveland, Montpelier, Columbia, Denver, and four destroyers), stood out of Havannah Harbor to bombard Kolombangara and the Shortlands. Warned of an incoming air attack while en route to Tulagi on 28 June, TG 36.2 joined with Sangamon and her screen to protect a transport convoy before steaming on at sunset after enemy planes failed to appear. Cleveland and TG 36.2 briefly stood into Purvis Bay to refuel on 29 June, where a destroyer minelayer group assigned to sew a minefield off the Shortlands during the bombardment joined them. Concerned about air attack and lurking enemy ships as it passed through the confined waters of the Slot at 26 knots, Merrill’s force enjoyed the lucky arrival of cloud cover, driving rainfall, and near zero visibility. Two destroyers steered at sunset for a repeat shelling of Vila airfield. On approach to the Shortlands, the destroyer minelayers split off at 0030 on 30 June to complete their mission and then retire separately. Merrill had assigned each remaining ship a designated area to strike; Cleveland’s was Korovo Point, at the eastern end of Shortland Island. Navigating and aiming via radar in rain so heavy that it obscured any observation of the objective, she slowed to 15 knots and opened fire to starboard at 0156 on a target area 750 yards in diameter. Over the next 15 minutes, Cleveland delivered 944 6-inch and 509 5-inch rounds through gun flashes both intensified and muffled by the dense precipitation. Capt. Shepard reported that “all hands performed their duty as if in target practice” and he expressed his “appreciation for the state of training to which Captain Burrough had brought the ship.” For his actions during the raid, Shepard received the Bronze Star. Mission accomplished, Cleveland and the rest of TG 36.2 rendezvoused with the minelaying force before shaping course south of New Georgia back to Purvis Bay.

On 1 July 1943, while the rest of TF 68 sailed for replenishment in Espíritu Santo, Cleveland, Denver, and two destroyers formed a new bombardment force in the Coral Sea with the fast battleship North Carolina (BB-55) and its screen. By the time the rest of Merrill’s force arrived on 5 July, however, North Carolina had left on another assignment and Halsey redirected TG 36.2 to Purvis Bay instead. The task group steamed up the Slot to Kula Gulf during the night of 6–7 July to cover two destroyers searching for survivors from light cruiser Helena (CL-50), torpedoed and sunk by the Japanese the night before. No enemy forces appeared and the destroyers rescued 81 sailors. Merrill’s force swept north of Kula Gulf on the night of 7–8 July. Cleveland’s anti-aircraft batteries briefly engaged an unidentified plane after it dropped flares astern of the formation but made no other contacts. After a short respite, Halsey sent TG 36.2 to patrol Kula Gulf, again uneventfully, on the night of 10–11 July.

Cleveland and her consorts stood out from Purvis Bay during the afternoon watch on 11 July 1943 to provide bombardment support for an Army ground assault on Munda Point that night. Reinforced with six additional destroyers to screen against air, surface, and submarine threats, CruDiv 12 steamed line ahead northwest through Blanche Channel during the mid watch on 12 July. Under partially overcast skies with a light breeze, Cleveland, fourth in column, slowed to 10 knots at 0304 and her 5-inch and 6-inch batteries fired upon designated targets 4.7 miles away. Aloft in a circling Black Cat, Lt. Occo D. Gibbs, Cleveland’s senior aviator, spotted for his ship and Denver. He reported that Cleveland’s sixth salvo had detonated an ammunition dump. Shepard thought the cruisers’ gunfire sufficiently accurate to strike targets as close as 300 yards to attacking Army forces, instead of the mile-wide buffer upon which they had insisted. Altogether, Cleveland delivered 37.2 tons of 6-inch and 28.5 tons of 5-inch ordnance that left multiple fires burning before her barrage ceased at 0333. The response from shore had been weak, erratic, and brief. She tracked Japanese snoopers harassing the column with flare illumination but no air attacks followed. Her anti-aircraft batteries drove off one plane that approached too brazenly. Shortly thereafter TG 36.2 retired to Guadalcanal.

While en route to Espíritu Santo on 13 July 1943 for replenishment, Merrill received orders from Halsey to reverse course and execute a night patrol off the coast of Rendova. Japanese destroyers had damaged three allied light cruisers with torpedoes in the Battle of Kolombangara the night before. For the next several weeks, Cleveland and CruDiv 12 and the Third Fleet’s destroyer and motor torpedo boat (PT) squadrons shouldered responsibility for naval surface operations in the Solomons. Merrill began splitting his cruisers into pairs to maximize their tactical flexibility and operational availability. Cleveland, Montpelier, and three destroyers steamed to Visu Visu Point off Kula Gulf during the night of 23–24 July to cover transports landing supplies and taking off wounded soldiers on New Georgia. The mission went off without a problem and Merrill’s force retired with the convoy. At 0545 on 24 July, two bogies closed on the formation and Cleveland and a destroyer took them under fire and drove them off. After refueling in Purvis Bay later that day, the two cruisers and their screen departed during the first dog watch to patrol east of San Cristobal Island.

For most of August, Cleveland spent time drilling at anchor in Segond Channel in Espíritu Santo or in underway exercises at sea. On 3–4 August 1943, a reunited TG 36.2, with Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia temporarily attached, practiced new fleet tactics in the Coral Sea with TG 36.3, Rear Adm. Forrest C. Sherman, commanding, which included Saratoga and Rear Adm. Harold W. Hill’s battleships Maryland, Colorado, North Carolina, and Massachusetts (BB-59) and their screens. Merrill’s force, now named TF 39, conducted fleet exercises again with Sherman’s and Hill’s commands from 30 August through 4 September. Third Fleet authorized ten days of rest and recreation in Sydney, Australia, for each of Merrill’s cruisers; Columbia departed first on 6 September. On 10 September, Cleveland began a seven-day availability to repair her No. 2 boiler, which entailed partially retubing it. The complexity of the repair required extending the availability until 22 September.

On 20 September 1943, TF 39 less Cleveland and Columbia (en route to Nouméa from Sydney) steamed from Espíritu Santo per Halsey’s orders to block the Tokyo Express from rescuing the garrison on Kolombangara. Three days later, Halsey directed Cleveland and two destroyers to form TG 39.2 and rendezvous with Columbia and her escorts in the Coral Sea. After refueling at sea, the task group shaped course to the northeast to sail around Vella LaValla and then back down the eastern coast of New Georgia during the night of 25–26 September to set a “mouse trap” ambush with TF 39 advancing up the Slot from Guadalcanal. The hunters became the hunted, however, as the Japanese had anticipated their arrival. At 0100 on 26 September, radar detected four unidentified aircraft closing on TG 39.2. Cleveland’s anti-aircraft fire drove off one that approached within 7,200 yards and while Columbia and the destroyers engaged the others. The snoopers followed them, hovering beyond gun range. Columbia reported sighting a torpedo wake off her starboard quarter at 0312 and the ships accelerated to 32 knots. Another torpedo passed astern of Cleveland. One of the destroyers fired upon a surface contact at 0334, which turned up on Cleveland’s radar two minutes later. Her starboard 5-inch guns took the target under fire until it disappeared from the screen. TG 39.2 joined up with the rest of TF 39 at 0600 and all stood in to Tulagi Harbor. TG 39.2 refueled and departed during the first dog watch to repeat the sweep up the Slot that night before Halsey thought better of it and recalled the ships a few hours later.

Cleveland returned to Espíritu Santo on 3 October 1943 and set course during afternoon watch the next day for Australia with Sterrett (DD-407) as escort. She moored in Sydney’s Woolloomooloo Bay on 8 October. On their first real break since arriving in the Pacific, Cleveland’s crewmembers mostly passed over rest in favor of recreation. They took advantage of the opportunity to blow off steam, drink Australian beer, and become acquainted with their allies “down under.” Two ship’s dances held at Sydney’s municipal auditorium highlighted the visit. As they later recalled, “A fine orchestra, free beer and soft drinks, an excellent floor show, and, of course, the charming Australian girls, combined to make these memorable occasions.” After ten short days, Cleveland and Sterrett stood out of Sydney for the return voyage to Espíritu Santo, where they anchored during the first dog watch on 22 October.

The Third Fleet had geared up for Operation Cherryblossom, the invasion of Bougainville Island, New Guinea [Papua New Guinea] by Halsey’s amphibious forces on 1 November 1943. The U.S. and British Combined Chiefs of Staff had agreed to bypass Rabaul and neutralize it instead using airpower staging from Bougainville. As a preliminary, Halsey called upon TF 39 to cover Operation Goodtime, the invasion of the Treasury Islands south of Bougainville, slated for 27 October. With Merrill and Montpelier en route from Sydney and Colombia under repairs in Espíritu Santo, Halsey designated Capt. Shepard to lead TG 39.3—Cleveland, Denver, and Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 23, comprising five destroyers commanded by Capt. Arleigh F. Burke. Sailing from Espíritu Santo to Purvis Bay, Tulagi, on 24–25 October, TG 39.3 sortied during the forenoon watch on the 26th to take station west of Ganongga Island [Ranongga Island], Solomon Islands. Shepard’s force tracked Japanese snoopers through the early hours of 27 October and one dropped two bombs near Denver at 0359. When the Goodtime invasion force and friendly air cover arrived at dawn, Cleveland and her consorts returned to Tulagi.

Halsey gave TF 39 multiple tasks on Cherryblossom’s D-Day: first, a bombardment of Japanese airfields on northern Bougainville early on 1 November 1943; followed by a diversionary barrage of the Shortland Islands at 0630; and then back north to protect the landing force assaulting Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay. Cleveland sortied from Purvis Bay at 0220, 31 October, in company with TF 39, comprised of CruDiv 12 and Capt. Burke’s DesRon 23 “Little Beavers,” which included Burke’s own Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 45 (Charles Ausburne (DD-570), Dyson (DD-572), Claxton (DD-571), and Stanly (DD-478)) and DesDiv 46 (Spence (DD-512), Foote (DD-511), Thatcher (DD-514), and Converse (DD-509)), led by Cmdr. Bernard L. Austin. Merrill’s force steamed up the Slot, west into the Solomon Sea, and then northwest to Bougainville. Tracking enemy snoopers, radar emissions, and a surface contact, TF 39 turned vigilantly onto the firing course at 2352. Beginning at 0023, 1 November, Cleveland hurled 750 6-inch and 493 5-inch rounds in 14 minutes onto pre-plotted targets on Buka airfield and adjacent supply and troop areas, setting off multiple large blazes. Soon after, her radar and lookouts spotted simultaneously two enemy small craft approaching at high speed, 500 yards off the port quarter. As the warship’s 40-millimeter guns opened fire, they abruptly reversed course. The after lookouts passed unconfirmed reports of torpedo wakes. Shepard ordered the rudder hard to port nevertheless and passed on the sighting report. TF 39 completed its fire mission and retired to the west while continuously engaging unidentified aircraft and surface targets (later suspected to be radar returns from clashing high-speed wakes). Enemy shore fire proved late and ineffective until a flare illuminated the cruisers and Montpelier suffered a near miss. A barrage from Cleveland’s 5-inch guns silenced the offending artillery. The task force changed course to the south and accelerated out of range. At dawn, U.S. fighters arriving over Bougainville found that TF 39 had rendered the airfields effectively inoperative.

The remainder of the night passed quietly as Merrill’s crews cleared decks cluttered with spent shell casings and empty powder cans, brought up fresh ammunition, and repaired blast damage. Cleveland and her consorts then closed on the Shortlands from the west to execute the first U.S. daylight naval bombardment in the Pacific. At 0619, enemy guns at Shortland Island’s southern tip opened up on the destroyers in the van, which silenced them. Unlike the previous barrage, Cleveland had no preset targets, but engaged shore guns—whose general locations her gunners already knew—at Shepard’s discretion. She also spotted with optics, not radar. At 0623, the captain gave the 5-inch battery permission to open fire, joined by the main battery six minutes later. For 35 minutes under clear and sunny skies, Cleveland peppered the islands with 1,250 5-inch and 493 6-inch shells. Straddled repeatedly by two-gun salvos from shore, she successfully evaded any hits. Of 16 guns observed shelling her, her gunfire neutralized all but four. At 0657, TF 39 retired to the east at 30 knots.

TF 39 slowed to loiter off Vella LaVella as the Bougainville landings commenced. During the forenoon watch, Merrill detached Burke’s DesDiv 45 to refuel in Hathorn Sound, 108 miles distant in Kula Gulf. The evening before, a reconnaissance plane had sighted Japanese cruisers and destroyers near Rabaul, heading north. That morning, the landing task force commander asked Merrill to intercept them should they turn south. Unknown at the time, the Japanese force, commanded by Vice Adm. Ōmori Sentarō, had attempted to surprise TF 39 in the Slot the night before. Having missed Merrill’s ships, Ōmori’s group returned to Rabaul where scout planes had spotted it, but it sortied again unobserved to attack the landing forces in Empress Augusta Bay. Anticipating Ōmori’s gambit, Merrill ordered his command northwest, recalled Burke’s destroyers, and asked for special reconnaissance of the enemy ships. Tracking planes verified two heavy and two light cruisers and six destroyers heading southeast from Rabaul. Merrill charted a course to intercept at 15 knots, slow enough to minimize detection but still ambush Ōmori off Cape Torokina. He planned a night engagement initiated with independent destroyer torpedo attacks followed by cruiser gunfire from the edge of enemy effective torpedo range. With CruDiv 12 Third Fleet’s sole heavy night fighting force available and the proven lethality of Japanese torpedoes, Merrill deemed it more prudent to bar the enemy from the landing forces rather than risk a battle of annihilation through close combat. The stage had been set for the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay.

As darkness descended, Cleveland and TF 39 steamed on smooth seas, with a light breeze from the south-southwest, detached clouds with ten percent cover, and visibility of six miles. An early moonset left the skies very dark. Merrill deployed his cruisers in line of battle, with Cleveland in her usual position astern of Montpelier, followed by Columbia and Denver. DesDiv 45 reunited with the task force at 2315 and worked its way into the van, while DesDiv 46 closed the column astern. A recon report at 0124 on 2 November 1943 placed the Japanese 83 miles away, steaming southeast at 25 knots. Merrill increased speed to 28 knots and predicted contact at 0230. A destroyer minelayer task group retiring on an opposite course warned TF 39 of a Japanese snooper following them. At 0227, Montpelier’s SG radar picked up the first of Ōmori’s ships off the port bow at range 22 miles. These gradually resolved into three groups sailing abreast to the southeast. Light cruiser Sendai led destroyers Shigure, Samidare, and Shiratsuyu to the north; heavy cruisers Myoko and Haguro formed the center; light cruiser Agano and destroyers Naganami, Hatsuzake, and Wakatsuki comprised the west wing.

Cleveland’s SG radar detected the Sendai group at 0232 and her main battery tracked the largest blip. Merrill released DesDiv 45 to attack and signaled Austin to countermarch to lead the cruiser column south at 0238. A minute later, he ordered CruDiv 12 to execute simultaneous 180˚ turns. As more enemy ships emerged on radar, Merrill sent Austin’s destroyers in at 0245. At 0247, Burke reported that DesDiv 45’s “guppies are swimming”—torpedoes away. While waiting for them to hit, Cleveland observed the Sendai group turn hard to starboard. A snooper—perhaps the one identified earlier—had dropped a flare that revealed the Americans bearing down. Evading DesDiv 45’s attack, the Japanese aimed a spread of over 20 of their own deadly Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedoes at CruDiv 12 as they turned. Now sighted, Merrill ordered his cruisers to commence firing at 0250 and turn abreast to the south-southwest. Cleveland hurled a laddered ranging salvo from her main battery at her target, now 11.25 miles to the northwest. As in Kula Gulf in June, all of CruDiv 12 targeted the nearest large radar return, which was Sendai. A blizzard of 6-inch shells set her afire and jammed her rudder. Ōmori’s force immediately returned fire but their tight salvos and illuminating starshells fell 2-3,000 yards short and ahead of the cruisers. As the northern group slowed and reversed course to dodge, Samidare and Shiratsuyu collided. Seeing the enemy turn away, Merrill steered CruDiv 12 to the southwest to maintain range. Cleveland’s main battery cycled to rapid fire but ceased altogether at 0256 as Sendai receded out of reach.

Cleveland then homed in on one of the heavy cruisers 11.8 miles to the west and Shepard resumed firing at 0302. Merrill ordered another simultaneous turn due north to close with the fleeing Sendai group and to clear DesDiv 46, which had crossed into the line of fire. Amid the din of battle and enemy fire, Cleveland and her sisters executed these intricate maneuvers by voice command alone (to their “everlasting credit” Merrill wrote later). Firing through the turn, Cleveland’s targeters reported an explosion and flames on her quarry and Shepard again held his fire at 0306. Hatsukaze blundered into Myoko’s path while evading incoming shells and lost a chunk of her starboard bow in the ensuing collision. At 0308, Foote reported taking a torpedo hit—one of the fish the Japanese had fired approximately 15 minutes earlier from over 12 miles away—that left her dead in the water. Moments later, a fortunate flash from either Montpelier’s guns or lightning revealed a ship missing most of her stern broken down right under Cleveland’s bow. Shepard ordered hard right rudder and avoided colliding with Foote by just 100 yards. As Cleveland passed through smoke and steam surrounding the disabled destroyer, bluejackets on deck smelled a chlorine-tinged odor that triggered a momentary poison gas alarm.

With Sendai burning and her escorts fleeing, Merrill ordered a simultaneous turn due south at 0312 to close on the Myoko and Agano groups. Enabled by starshell and flare illumination, the gunfire from Ōmori’s ships improved in accuracy. Several projectiles impacted just under Cleveland’s forefoot, dousing her with water. One salvo straddled her abreast the forward engine room and one or more shells struck below the waterline but failed to penetrate her armored belt. At 0316, Cleveland recommenced salvo fire on the heavy cruiser she had engaged previously. As the opposing formations charged down converging courses, Myoko and Haguro launched torpedoes at CruDiv 12 at 0318. An 8-inch shell hit Denver at 0320 that fortunately did not explode. Merrill ordered his cruisers to fire starshells to counter-illuminate the enemy line and then turn to course 200˚ to throw off their targeting. Denver was hit twice more by 8-inch dud rounds, one of which opened a hole on her waterline forward that forced her out of the battle line. Now well within enemy torpedo range, Merrill ordered CruDiv 12 to make smoke and turn away to the northeast at 0326. The U.S. cruisers’ sudden disappearance from view led Ōmori to think his Long Lances had sunk them. He ordered his force to retire to the northwest at 0329, believing he had successfully engaged seven enemy cruisers and sixteen destroyers. Cleveland ceased firing at 0330 and unloaded her main battery “through the muzzles” by firing harmlessly at the sea. As Merrill maneuvered his cruisers onto a southwesterly course, Denver rejoined the formation. The destroyers pursued until 0457, finishing off Sendai and the hapless Hatsukaze along the way. Although Burke wanted to keep going, Merrill ordered him to collect his squadron and rejoin the cruisers, having fulfilled the mission of protecting the landing forces in the bay.

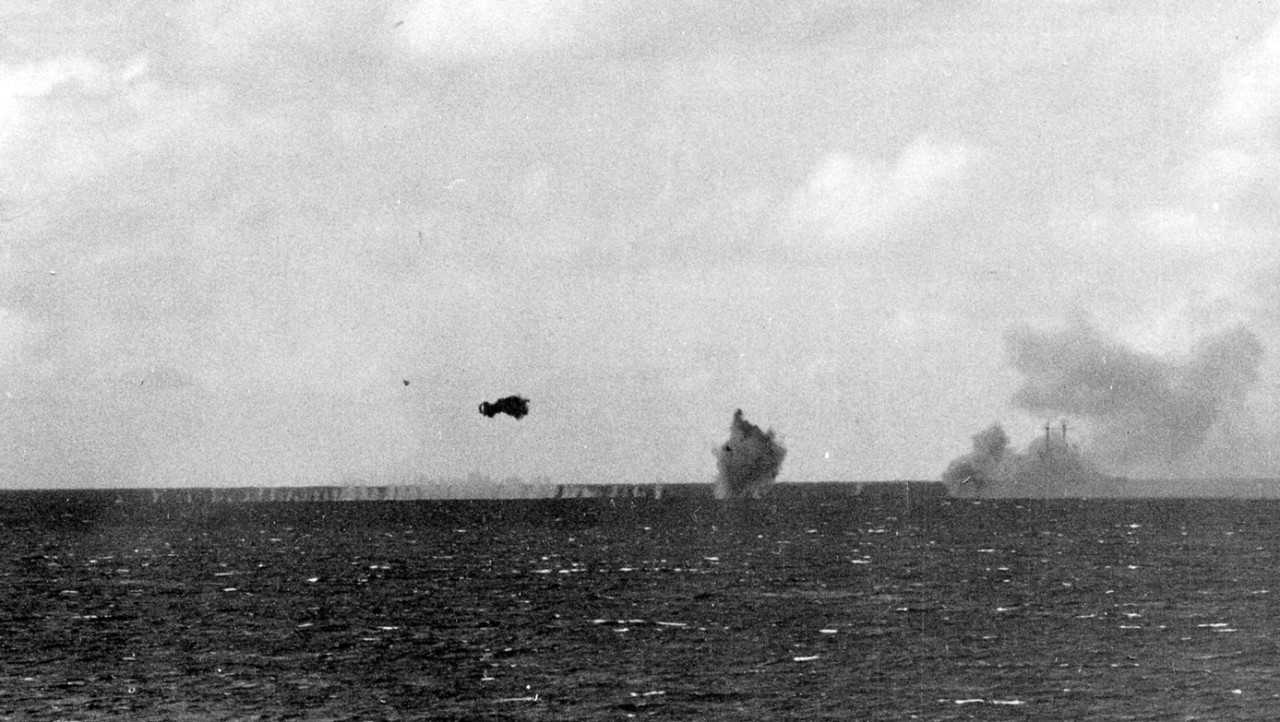

A Japanese scout plane approached TF 39 at 0559 as it returned to Foote and Merrill requested friendly air cover. He detached Charles Ausburne and Thatcher to escort Foote, which had been taken under tow by Claxton. The rest of the force steamed toward Empress Augusta Bay. Under clear skies and smooth seas, Merrill ordered his ships into a circular anti-aircraft formation and then to General Quarters. At 0745, he radioed his captains that radar had picked up “many bogies” 59 miles out, approaching from the northwest. These were 18 Aichi D3A Type 99 (Val) carrier bombers and 80 Mitsubishi A6M Zero-Sen Type 0 (Zeke) carrier fighters from the Zuikaku, Shōkaku, and Zuiho air groups temporarily based in Rabaul. Cleveland’s fire control radar began tracking them at 0758. As a group of 28 enemy aircraft arrived overhead along with friendly CAP, Merrill ordered the task force to execute a series of simultaneous emergency 360˚ turns to spoil the attackers’ aim. Cleveland’s anti-aircraft battery commenced firing at 0804. Three minutes later, a group of three Vals lined up on her and nosed over into shallow dives from 12,000 feet. Two bombs landed to starboard and one exploded amidships to port, throwing water and fragments on board. They caused no damage but did trip four circuit breakers that electricians reset so quickly that few even noticed losing power and light. The attack lasted just 13 minutes and scored only two bomb hits, both on Montpelier’s starboard catapult. Cleveland’s 40-millimeter gunners claimed two kills and her 5-inch battery shot down another with a mixture of Mk. 32 and regular ammunition. TF 39 reported downing 10–15 enemy planes altogether. The attackers reformed for another run but additional U.S. fighters vectored out from the director station at the beachhead chased them off, splashing eight more aircraft.

With his crews exhausted, ammunition running low, and Austin’s destroyers urgently needing to refuel, Merrill wanted to return to base but Halsey sent TF 39 back to Empress Augusta Bay to cover another wave of transports. A front brought foul weather to the area, decreasing the potential for Japanese air attack and at 1930, Merrill handed off the transports to light cruiser Nashville (CL-43) and destroyer Pringle (DD-477) and shaped course for Port Purvis. Arriving back during the first dog watch on 3 November 1943, all hands enjoyed sleep for the first time in nearly four days. The tug Sioux (AT-75) towed Foote into port that afternoon to cheers and yawns from TF 39’s sleepy crews.

Of the service of his officers and crew over those four memorable days, Capt. Shepard wrote simply “[A]ll hands performed their duties in accordance with the high standard expected of them.” For their roles in the actions of 1-3 November, Shepard received the Navy Cross and Cmdr. Ernest St. C. Von Kleeck, Jr., executive officer, was awarded the Legion of Merit. Letters of commendations were given to several officers for their performance of duty: Cmdr. Earl V. Sherman, navigation officer; Lt. Cmdr. John H. Carmichael, gunnery officer; Cmdr. William V. McKaig, engineering officer; Lt. Cmdr. L. A. Harrison, Jr., communications officer; Lt. (jg) Amos J. Hobson, electrical officer; Lieutenant Gervis G. Morrison, commanding the secondary battery; Electrician (T) Melvin Bouslog, assistant electrical officer; Lt. (jg) Bruce M. Thompson, radar officer; and Lt. Thomas J. Rudden, Jr., main battery spotter. Among the crew, CBM (AA) Clarence H. Craver; CFC (AA) Paul Hood; BM1c Lavern King; S2c Marvin D. Massey; GM3c Joseph G. Day; and RdM1c Thomas L. Conway also received commendation.

With Nashville temporarily replacing the damaged Denver, TF 39 departed Purvis Bay at 1800 on 4 November to continue escorting landing echelons to Empress Augusta Bay. Merrill sent Cleveland, Nashville, and three destroyers to refuel in Hathorn Bay on the night of 6–7 November. Early on 7 November, he recalled his detachment and steamed with the rest to intercept a reported Japanese force of two light cruisers and five destroyers north of Bougainville. Unable to locate the enemy, TF 39 reassembled northwest of Treasury Island during the forenoon watch. Relieved by Rear Adm. Laurence T. DuBose’s CruDiv 13 that evening, Merrill’s ships returned to Tulagi early the next morning.

After this flurry of activity, Cleveland experienced several weeks of relative quiet resting her crew at anchor in Purvis Bay while ground forces secured Bougainville. With Denver bound for repairs and refitting in the U.S. after taking a torpedo off Cape Torokina on 13 November 1943, Halsey approved the installation of her state-of-the-art fire control radar in Cleveland early in December. TF 39 sortied on 7 December to confront a suspected Japanese task force sailing from Rabaul, but returned to base on 9 December after making no contacts. The effects of inactivity showed up when Merrill’s force conducted a diversionary bombardment on northern Bougainville early on Christmas Eve. Under clear but slightly overcast skies and a moonless night, Cleveland commenced her part of the barrage at 0041 but her new radar went out of commission four minutes later. Although she still put 858 6-inch and 869 5-inch rounds on target in 10 minutes, gun blindness caused her overanxious secondary gun crews to fumble while loading, slowing their rate of fire. Shepard attributed this to the lack of underway training over the previous six weeks.

CruDiv 12 marked its first year in the Pacific with another extended period of upkeep, recreation, and training in Espíritu Santo (4–27 January 1944), which included three days for Cleveland in the advanced base sectional dock ABSD-1 undergoing routine overhaul (12–14 January). Merrill began shaking the rust off his crews with a series of daily underway exercises. TF 39 sailed on 27 January to return to Purvis Bay and conducted night battle exercises en route with Rear Adm. Walden L. Ainsworth’s TF 38.

By mid-February 1944, the Third Fleet stood ready to complete Operation Cartwheel. TF 39 departed from Tulagi during the first dog watch on 13 February to provide distant coverage for Operation Squarepeg, the invasion of the Green Islands, New Guinea [Papua New Guinea] by combined U.S. and New Zealand forces. To keep the Japanese in the dark about its presence, Merrill’s force operated under strict radio and radar emissions discipline to arrive on station undetected. Cleveland and her consorts patrolled off the coast of Green during the nights and retired seaward during the day. The mission proved uneventful as TF 39 encountered no enemy aircraft or ships. Halsey ordered CruDiv 12 to return to Purvis Bay on 17 February while Burke’s DesRon 23 conducted an anti-shipping sweep around Kavieng.

Following another stretch at anchor in Purvis Bay (19 February–4 March 1944), Cleveland and TF 39 put to sea on 5 March for an anti-shipping sweep off New Ireland between Kavieng, Rabaul, and Truk. Adm. Merrill’s ships exercised and drilled underway while again operating under radio and radar discipline. CruDiv 12’s scout planes searched for enemy shipping but found the seas cleared of targets. Merrill’s force returned empty handed to Tulagi on 11 March. After rehearsing shore bombardment off Guadalcanal on 15 March, TF 39 got underway from Port Purvis two days later, assigned to provide close in cover and fire support landings on Emirau Island, St. Mathias Islands, New Guinea [Papua New Guinea] on 20 March, the final operation to isolate Rabaul. U.S. Marines arrived ashore unopposed so Merrill’s force was released to hunt shipping in the Truk-Rabaul-Kavieng area. Finding nothing, Halsey sent TF 39 back to Tulagi on 22 March.

The officers and crews of CruDiv 12 said goodbye to “Tip” Merrill on 26 March 1944, who was relieved by Rear Adm. Robert W. Hayler. On 4 April, Columbia sailed for overhaul at Mare Island Navy Yard in California, reducing CruDiv 12 to only Cleveland and Montpelier. The next day, the two cruisers, screened by five destroyers, sailed for Sydney for ship repairs and recreation (9–17 April). Hayler’s task force returned to Purvis Bay on 17 April, where it remained at anchor, expect for underway drills (26 April) and exercises at sea (1–3 May).

CruDiv 12 steamed to Hathorn Bay on 6 May 1944, to report for duty with Fifth Fleet under Vice Adm. Raymond A. Spruance and prepare for Operation Forager, the invasion of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, in the Mariana Islands [Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands]. For the rest of the month, Hayler’s ships engaged in intensive bombardment exercises at various locations in the Solomon Islands. On 20 May, Cleveland unexpectedly ran up against an old adversary: the Japanese garrison on Shortland Island, bypassed months earlier. Following a practice barrage from her 6-inch main battery, surprised observers spotted a five-gun return salvo from shore that straddled Cleveland’s track 50 yards ahead. The guns straddled her twice more abreast the foremast. As she returned fire, Shepard turned his ship toward the guns and increased speed. The next enemy shells landed 500 yards over as Cleveland reached 30 knots and then veered away sharply. Four more enemy salvos missed short. The Japanese straddled Montpelier several times and hit her once, wounding six and inflicting superficial damage. Taking up position just outside enemy gun range, Cleveland pummeled her antagonists until their fire slackened and then ceased. In all, she expended 1,041 6-inch and 135 5-inch rounds before the exercise ended.

On 4 June 1944, CruDiv 12 proceeded to Kwajalien Atoll where it joined TF 52 Northern Attack Group, led by Vice Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner, the overall commander of Forager’s amphibious forces. Turner assigned Hayler to lead TU 52.17.5 Fire Support Unit Five, comprising Cleveland, Montpelier, and three destroyers, part of Rear Adm. Jessie B. Oldendorf’s TG 52.17 Fire Support Group 1. Cleveland and her consorts departed Kwajalein at 0750 on 10 June, bound for Saipan Island in the Marianas. Upon arrival on 14 June, D-1, Cleveland and Montpelier split up to bombard identified enemy gun emplacements and counterbattery targets of opportunity on the eastern and southern shores. Strict Japanese fire discipline and effective camouflage left the impression the defenders had abandoned the island until Cleveland observed an impatient gun crew open up on Montpelier in the early evening only to be smothered by her rapid-fire response. Cleveland supplied harassing fire through the night. The landings commenced on 15 June and for the next two days, she shelled preset locations and targets of opportunity during daylight, and serviced call for fire requests from troops ashore and harassment barrages through the night. Hayler commended the “smooth performance” of his cruisers, attributing it to the “intense training program during an adequate preparatory period.”

Cleveland’s mission changed abruptly on 17 June 1944. Warned by submarines that units of the Japanese First Mobile Fleet, commanded by Vice Adm. Ozawa Jisaburō, were moving east from the Philippines, Spruance elected to concentrate the available fast battleships in anticipation of a night surface engagement. To substitute for them, Turner attached CruDiv 12 to Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher’s TF 58 Fast Carrier Task Force to screen TG 58.3 Carrier Task Group Three, commanded by Rear Adm. John W. Reeves, comprised of carriers Enterprise, Lexington (CV-16) [with Mitscher embarked], San Jacinto (CVL-30), and Princeton (CVL-23), heavy cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35) [with Spruance embarked], light cruiser Reno (CL-96), and 13 destroyers. After replenishing ammunition that morning, Cleveland took her station in the carrier formation at 1815. TG 58.3 sailed west from the Marianas into the Philippine Sea conducting air searches throughout the daylight hours on 18 June, but after failing to locate any Japanese forces, it retired eastward after dark.

As TF 58’s carriers turned east into the wind to launch aircraft on the morning of 19 June 1944, the weather broke fair and clear, with few clouds and unlimited ceiling and visibility. Cleveland’s air search radar picked up several large groups of unidentified contacts approaching from the west at range 140 miles at 1007. This raid, one of four launched by the First Mobile Fleet that day, consisted of 109 Yokosuka D4Y Suisei (Judy) carrier dive-bombers, Nakajima B6N Tenzan (Jill) carrier torpedo-bombers, and Zeke fighters sent from the carriers Taihō, Shōkaku, and Zuikaku. TG 58.3’s carriers launched all planes on deck and the formation went to General Quarters at 1038. Fighter directors vectored the task group’s CAP onto the oncoming enemy planes, virtually annihilating them. (Reeves’ fighters claimed 95 of over 350 Japanese planes shot down that day, known thereafter as “The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”) Only four Jills reached the formation and three attacked on Cleveland’s side. She maneuvered evasively on signal as the first Jill started its run. Her starboard anti-aircraft batteries opened fire at 1159 at a range of 2,500 yards and combined with Princeton to bring the target down in flames. Cleveland’s gunners claimed a second Jill, which caught fire and splashed 2,000 yards on the starboard quarter. Ships in her line of fire prevented Cleveland from engaging the third but Princeton splashed it on her own. Montpelier brought down the fourth. “The performance of [Cleveland’s] personnel was excellent,” Shepard observed in his report.

TF 58 finally located the First Mobile Fleet’s aircraft carriers on the afternoon of 20 June 1944 and Mitscher ordered a late day air strike that required his pilots to make risky night landings upon returning. U.S. submarines had sunk carriers Taihō and Shōkaku the day before; Mitscher’s aviators sent Hiyō to the bottom and damaged carriers Zuikaku, Junyō, and Chiyoda and battleship Haruna. They also left the First Mobile Fleet with just 35 operational aircraft. TF 58’s strike planes began to arrive back at 2000. Mitscher ordered Cleveland and all his capital ships to turn on lights and fire star shells to guide in the planes. TF 58 pursued the retreating Japanese through 21 June but could not close enough for more attacks. Spruance continued the chase with the fast battleships and one carrier task group while the rest of TF 58 turned east during the first watch that night to rendezvous with tankers, bringing the Battle of the Philippine Sea to a close.

Hayler’s cruisers returned to Saipan on 25 June 1944 where they resumed harassment fire and on-call gunfire support duties. Turner temporarily detached CruDiv 12 to TF 53 Southern Attack Force (Rear Adm. Richard L. Conolly) on 20 July to augment bombardment support for the invasion of Guam. As the landings commenced the next morning, Cleveland fired upon targets of opportunity and responded to calls for fire before steaming back to Saipan with Montpelier that night.

Turner again detached Cleveland to support the invasion of Tinian scheduled for 24 July 1944. She joined TU 52.17.3 Fire Support Unit Three (Rear Adm. Theodore D. Ruddock, Jr., commanding, with battleship Colorado, and destroyers Remey (DD-688), Wadleigh (DD-689), Norman Scott (DD-690), and Monssen (DD-798)) to conduct preliminary bombardment on the southwest part of the island on 23 July. At 0742 on D-Day, 24 July, a previously unseen large-caliber shore battery south of Tinian Town hit Colorado 22 times, killing 43, wounding 196, and leaving four missing. Japanese gunners then struck Norman Scott six times in rapid succession, killing her commanding officer and 18 others, and wounding 63. Cleveland’s main and secondary batteries responded promptly, finding the target with her second salvo. As they shifted to rapid fire, her 20-millimeter and 40-millimeter guns joined in. The sheer volume of her own gunfire enveloped Cleveland in smoke, leading nearby light cruiser Birmingham (CL-62) to report that the Japanese had hit her as well. Shepard happily refuted the claim and declared the enemy batteries silenced at 0759. For meritorious conduct as the officer in charge of Cleveland’s forward main battery that day, Lt. Thomas J. Rudden, Jr. received a Gold Star in lieu of his second letter of commendation.

Cleveland reported to Adm. Conolly’s Southern Attack Force on 29 July 1944, which assigned her to TU 53.5.3 (Rear Adm. C. Turner Joy, commanding, comprising heavy cruisers Wichita and Minneapolis (CA-36), light cruiser St. Louis (CL-49), and screen). She serviced calls for fire from shore and tackled targets of opportunity in support of ground forces on Guam though 9 August, which was declared secure the next day. Except for her stint screening carriers, Cleveland had provided nearly seven weeks of fire support, a demanding and tedious, yet indispensable, task. “Throughout, from start to finish, every officer and man turned in a first class, professional performance,” Capt. Shepard reported. He singled out Cmdr. von Kleeck and Lt. Cmdr. Carmichael once more as most responsible for this. Shepard was awarded the Silver Star for his performance in the Marianas invasions and the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Cleveland’s aviation detachment received recognition for its contribution. SOC-1 Seagull seaplane pilots Lt. Donald Allison and Lt (jg) Frank J. Butler, Jr. received Air Medals for meritorious achievement, and ARM2c Willis A. Barber and ARM3c Robert P. Sims were given commendations for excellent service.

Cleveland rejoined CruDiv 12 in Eniwetok on 12 August 1944. Hayler’s pennant flew in the repaired and refurbished Denver as Montpelier returned to the U.S. for refitting. A 100-man party spent the next day on Runit Island, the first recreation ashore Cleveland’s company had enjoyed since early June. On 14 August, Capt. Herbert G. Hopwood relieved Shepard as commanding officer, and as he became acquainted with his new command, CruDiv 12 put to sea on 18 August to return to Purvis Bay. Underway exercises en route revealed that Cleveland’s anti-aircraft proficiency had fallen off during bombardment duty. Upon arrival on 22 August, CruDiv 12 reported for duty once again with Adm. Halsey’s Third Fleet. Columbia returned from stateside overhaul on the 23rd and joined her sisters in intensive rehearsals for landing fire support operations to prepare for Operation Stalemate II, the invasion of Peleliu and Angaur Islands, Palau Islands [Republic of Palau].

Assigned to TU 32.12.1 Fire Support Unit 1 (Rear Adm. Howard F. Kingman, commanding, with Tennessee (BB-43), Minneapolis, and 5 destroyers), Cleveland arrived off Anguar on 12 September 1944 and commenced shore bombardment on schedule at 0630. Her war diarist recorded that “There was no sign of life on the island and no return fire was received.” She provided covering fire for Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) reconnoitering and clearing beach obstacles. That night and for several thereafter, she retired to open water with the task unit before returning to station in the morning. Cleveland took on 2 officers and 74 crewmen from destroyer minelayer Perry (DMS-17) which had been sunk by a mine on 13 September. After Cleveland’s doctor examined them, they received a meal, clothing, toilet articles, cigarettes and medicinal brandy, bunks and lockers. She fired barrages in support of the landings on 15 September and provided on-call fire until organized resistance ended three days later. Reassigned to TF 32 (Rear Adm. George H. Fort) on 24 September, Cleveland began firing in support of ground forces on Peleliu. Her rusty anti-aircraft batteries drove off a lone Japanese snooper on the 26th. She provided bombardment support for a marine assault on nearby Ngesebus Island on 27–28 September. Released from her duties the next day, Cleveland proceeded on to Manus Island, Admiralty Islands [Papua New Guinea] in company with a task unit under Rear Adm. Ainsworth, where she dropped anchor on 1 October.

Cleveland departed on 5 October 1944, bound for a long-anticipated overhaul in the U.S. Mooring overnight in Pearl Harbor on 14–15 October, she arrived at Terminal Island, San Pedro, California, on 21 October. Her return proved a momentous occasion for all on board. To their disappointment, Cleveland’s complement received only 23 days of leave after two years away, but they were needed to participate in her extensive refit. In dry dock from 25 October to 6 December, workers upgraded her radar and fire control systems and installed a modern Combat Information Center (CIC). They regunned all of her batteries and doubled the heavy machine guns on board. With work completed, Cleveland took on ammunition and stood out for post-repair sea trials off the southern California coast on 12 December. She took part in various sea exercises through the end of the month but spent Christmas at anchor in San Pedro with the venerable battleships New York, Nevada (BB-36), and Arkansas (BB-33).

On 3 January 1945, Cleveland departed for her second tour of duty in the Pacific with a handful of new officers and 200 raw draftee crewmembers. Underway gunnery drills and tactical exercises helped teach the new sailors and reacquaint her veteran bluejackets with their combat responsibilities. Arriving at Pearl Harbor on 9 January, she stood out again on the 14th in company with Indianapolis, commanded by Capt. Charles B. McVay III, Cleveland’s former executive officer, and with Vice Adm. Spruance embarked. Anchoring overnight in Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands [Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia] on 25–26 January, Cleveland arrived in San Pedro Bay, Leyte Island, Philippine Islands [Republic of the Philippines] on the 28th. The next day she cruised to Mangarin Bay, Mindoro Island, Philippine Islands, where she anchored with CruDiv 12 (less Columbia), now under the command of Rear Adm. Ralph S. Riggs. Army forces under General MacArthur had landed on Luzon Island, Philippine Islands, on 9 January and were advancing on the capital city of Manila. Cleveland and her sisters, now assigned to Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid’s Seventh Fleet, shifted to Subic Bay, Luzon, on 9 February to support amphibious landings to occupy Corregidor Island and the southern Bataan Peninsula.

Constituted as TU 77.3.2 Fire Support Unit “B” under Riggs, Cleveland, Denver, Montpelier, and five destroyers guarded minesweepers operating in Manila Bay and bombarded targets on Corregidor beginning on 13 February 1945 while returning to Subic Bay each night. The Japanese initially exhibited strict fire discipline and betrayed little evidence of their presence. When shore guns on the smaller islands in the bay began targeting the minesweepers on the 14th, Cleveland supplied suppressive counterbattery fire. She bombarded Corregidor again on 15 February as assault forces landed in Mariveles Harbor across the bay that morning to little opposition. At 0800 on 16 February, Cleveland took station off Corregidor, where she observed Army transport planes begin dropping paratroopers 30 minutes later. She commenced bombardment at 0949 and amphibious landing troops from Mariveles Harbor arrived at the beaches at 1030. After spending 17 February moored in Subic Bay, Cleveland returned to Corregidor on 18 February but only contributed one of her scout planes for observation to the battle. Capt. Hopwood received a letter of commendation for excellent service in support of these operations in Manila Bay.

Released from support duty, CruDiv 12 departed for Mangarin Bay on 24 February 1945 to provide fire support for Operation Victor III, the invasion and occupation of Puerto Princessa, Palawan Island, Philippines Islands. Organized as TG 74.2 under Rear Adm. Riggs’ command, CruDiv 12 and four destroyers arrived off Puerto Princessa on the morning of 28 February and commenced a scheduled preparatory bombardment at 0713. The first landing wave reached shore at 0849 to no opposition. Its participation no longer needed, TG 74.2 retired to Subic Bay during the first dog watch that evening. Riggs’ task group shifted to Mangarin Bay on 9–10 March to stand by to support ongoing operations on Mindanao, but was redirected to Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, instead on 11 March to join in the forthcoming Operation Victor I landings in Iloilo, Panay Island, Philippine Islands. Riggs’ ships reached Mangarin Bay on 15 March, where it was determined that only one cruiser was necessary for Victor I. On 17 March, Cleveland and destroyers Conway, Eaton (DD-510) and Stevens (DD-479), constituted as TU 74.2.2 with Capt. Hopwood in command, set out for southern Panay. Reaching her designated station at 0658 on 18 March, Cleveland catapulted two scout planes into the air to conduct reconnaissance and observation. The first assault wave landed without opposition and she received no calls for fire support. After two more quiet days, TU 74.2.2 departed to rejoin CruDiv 12 in Mangarin Bay on 20 March. TG 74.2 returned to Subic Bay on 22 March.

Cleveland sailed to Manila Bay on 4 April 1945 to allow a group of officers and crew to undertake a six-hour guided sightseeing walking tour of the city, once beautiful and historic, now with many sections reduced to rubble. At 0300 on 8 April, CruDiv 12 sortied with TF 74 (Rear Adm. Russell S. Berkey, commanding) from Subic Bay to intercept a Japanese heavy cruiser and destroyer reportedly sailing south from Formosa. When no enemy contacts or follow on reports turned up, the task force returned to base at 0910.

While at sea on 10 April 1945 conducting gunnery and tactical exercises with TF 74, Riggs’ TG 74.2 received orders to divert to Mangarin Bay to stage for the forthcoming Operation Victor V landings in the Malabang-Cotabato area of Mindanao. With flags at half-staff on news of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death, TG 74.2 departed on 14 April en route to Illana Bay, Mindanao. Cleveland and two destroyers, designated Fire Support Unit 3, proceeded to their assigned firing area during the mid watch on 17 April. She fired her scheduled bombardment near Cotabato City from 0640–0806. Once again, the landings were unopposed and Cleveland received no calls for fire support that day. Fire Support Unit 3 returned the next morning to deliver another planned bombardment. Cleveland did provide 5-inch battery fire at 0925, but the rest of the day was quiet. When the 19th proved uneventful as well, Riggs released Cleveland to return to Subic Bay. From 30 April to 6 June, Cleveland and TG 74.2 conducted various drills, training exercises, and tactical problems while awaiting a new mission. TG 74.2 set course for Brunei Bay, British North Borneo [East Malaysia, Malaysia] on 7 June to provide distant cover for Oboe VI, landings by Australian forces scheduled for 10 June. Cleveland anchored in Brunei Bay on 11 June while her scout planes flew reconnaissance and gunfire spotting missions for the landing forces through the 14th.

On 15 June 1945, Cleveland shaped course back for Subic Bay with a special assignment, to carry MacArthur to observe Operation Oboe II, the allied invasion and occupation of Balikpapan, Dutch Borneo [Kalimantan, Indonesia]. She embarked the general and his staff in Manila Bay during first dog watch on 27 June. Escorted by two destroyers, Cleveland stopped briefly at Tawi Tawi, Philippine Islands on 29 June to receive the general’s mail. After reporting for duty off Balikpapan on 30 June, Cleveland took her assigned station the next morning and performed a bombardment mission from 0700–0925. During the forenoon watch, Vice Adm. Daniel E. Barbey, Commander, Amphibious Force, Seventh Fleet; and Australians Lt. Gen. Leslie J. Morshead, Lt. Gen. Edward J. Milford, and Vice Air Marshal William D. Bostock, embarked for an official call on MacArthur. The party debarked for an inspection tour of landing area at 1129 and returned at 1504. By 1551, Cleveland and escorts were shaping course back for Manila. After rendezvousing with a courier plane at Tawi Tawi, Cleveland anchored in Manila Bay during afternoon watch on 3 July and disembarked MacArthur with all honors except no salute was fired. That same day, Capt. Charles J. Maguire relieved Hopwood as commanding officer. (Hopwood was awarded a Gold Star for exceptionally meritorious conduct for his tenure as Cleveland’s skipper.) Maguire ordered his ship to sea shortly thereafter to rejoin TG 74.2 and steam to San Pedro Bay, where she anchored on 5 July.

Cleveland stood out during the morning watch on 13 July 1945 in company with TF 95, commanded by Rear Adm. Francis S. Low. This fast, hard-hitting force, which included all four ships of CruDiv 12, CruDiv 16 (large cruisers Alaska (CB-1) and Guam (CB-2)) and nine screening destroyers, had orders from Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, to conduct an anti-shipping sweep in the East China Sea. While proceeding on northerly courses, Low put his command through a series of drills and tactical problems to develop unit familiarity. After refueling in Buckner Bay, Okinawa Island, Ryūkyū Islands [Nansei Islands], on 16 July, a typhoon moving northward from the South China Sea forced TF 95 to retire southeast to sea for three days. Resuming a westerly course under excellent weather, Cleveland and her consorts entered the East China Sea on 21 July. The task force began encountering floating mines that the destroyers detonated with gunfire. Cleveland’s radar detected an unidentified aircraft during the first watch that night. After Guam, Alaska, and Denver fired upon it, the plane passed clear of the formation. With the enemy aware of its presence, TF 95 arrived off China near Fuzhou and at 0542 on 22 July, turned to the northeast to make a high-speed run up the coast. Marine Vought F4U Corsair fighters took station overhead at 0740 and remained until dusk. The only shipping TF 95 found was about 40 vessels identified as Chinese fishing junks. At 1415, Low ordered his formation to turn to the southeast to retire back to Buckner Bay, where it anchored during the afternoon watch on 24 July. Maguire reported that while Cleveland’s “Personnel performance was up to the usual high standards… [i]t is considered that the prospects of a strong surface force finding fruitful shipping targets in daylight sweeps along the China Coast south of the Yangtze are now nil.”

Redesignated TG 95.2 Light Striking Force, Cleveland and consorts sortied from Buckner Bay on 26 July 1945 for a coastal nighttime patrol off the southeastern approaches to the Yangtze River. Covered by two Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer patrol bombers, Low’s cruisers formed column at 1830 on 27 July with destroyers screening ahead and closing the formation astern. Steaming at 25 knots on light seas and swells, with bright moonlight overhead, one destroyer fired upon a junk and then rescued ten survivors, one of whom died the next day. The only enemy force seen was a snooper. Fighters replaced the bombers overhead at dawn on 28 July and TG 95.2 shaped course back to Buckner Bay during afternoon watch.

After postponing a day due to a scarcity of aviation gasoline on Okinawa for combat air patrols, Cleveland once again set out in company with TG 95.2 to hunt enemy shipping off the mouth of the Yangtze River on 1 August 1945. The arrival of another typhoon forced the task group to divert south for a day. At 2300 on 3 August, Low released Cleveland and CruDiv 12 with screening destroyers to sweep independently inshore. They investigated a radar contact that turned out to be a two-masted fishing junk before returning to the main formation. The destroyers made another empty-handed run during the night of 4–5 August. At 1426 on 5 August, radar detected two Yokosuka P1Y1 Ginga Frances twin-engine land bombers. Cleveland vectored in the overhead CAP, which splashed one while the other escaped at high speed. The circling fighters shot down another Frances a couple hours later. Low sent the destroyers on another inshore night sweep on 5–6 August. TG 95.2 shaped course back for Buckner Bay during the afternoon watch on 6 August and anchored the next day. In his report, Maguire noted that considerable confusion resulted from misidentification of the planet Venus as a twin-engine aircraft or balloon. He wryly recommended that CIC and all lookouts “be informed, in advance, of the bearing and altitude of the planet.”

On 8 August 1945, amid constant alerts of incoming enemy aircraft, rumors circulated among the ships in Buckner Bay that the U.S. had dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. Two evenings later, rockets, tracers, and flares spontaneously burst out from the beach area. Cleveland went to General Quarters but detected no aircraft on radar nor were any reported. An Armed Forces Radio report that Japan was willing to accept terms for surrender had prompted the fireworks, but Cleveland’s officers and crew remained skeptical and no ship in the bay joined in the display. Their caution proved justified. While at anchor at 2050 on 12 August, an underwater explosion jolted the ship. Pennsylvania soon reported taking an aerial torpedo from a low-flying Japanese plane that had approached low from seaward with running lights showing. The next day, Rear Adm. Oldendorf, the senior officer present afloat, ordered that all ships put to sea at night.

Japan announced its surrender on 15 August 1945 but Navy forces remained at combat alert even after the Japanese grounded all aircraft on 20 August. Cleveland continued wartime exercises and drills after Japanese officials signed surrender documents in Tōkyō Bay on 2 September. On 9 September, she stood out of Buckner Bay, assigned to TU 56.5.1 Wakayama Covering Unit, Rear Adm. Calvin T. Durgin, commanding, with escort carrier Makin Island (CVE-93), Denver, and four destroyers, to support evacuation of U.S. and allied personnel from Japanese prisoner of war and internment camps. Steaming off the coast, TU 56.5.1 followed battleship New Jersey (BB-62), Adm. Spruance’s flagship, into the harbor at Wakanoura Wan, Wakayama, Honshū Island, Japan, and anchored during the forenoon watch on 15 September.

Cleveland weathered a typhoon there on 17–18 September 1945. As winds gusted up to 80 knots, she alternated between dragging anchor and using engines to avoid other ships. Conditions gradually abated but several smaller vessels were damaged or beached and two Navy officers and four sailors were lost. Cleveland and Denver provisioned 25 smaller landing and support craft and stood by with CruDiv 12 to provide fire support if needed for Army occupation landings that took place on 25 September without incident. After enduring two more typhoons (2–4 and 9–11 October), Cleveland departed Wakanura Wan on 28 September and anchored near Yokosuka Naval Base in Tōkyō Bay on the next day. She ended three years of wartime service without suffering a personnel casualty or direct damage from enemy fire.

At 0616 on 1 November 1945, Cleveland left Japan bound for Boston, Massachusetts. After a stopover in Pearl Harbor (9–11 November), she sailed in company with Columbia before proceeding independently to San Diego, where she moored at Navy Pier on 17 November. She transited the Panama Canal on 27–28 November and arrived in Naval Shipyard, Boston, at 1452, 5 December to begin an extensive overhaul.

On 1 January 1946, Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, CINCLANT, redesignated CruDiv 12 as CruDiv 14 and assigned it to the newly-formed Fourth (Reserve) Fleet (Rear Adm. Thomas R. Cooley). Adm. Nimitz, now CNO, assigned Cleveland and CruDiv 14 to a training cruise in April for recent graduates of the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps and V-12 Naval College Training Program, with Rear Adm. Riggs acting as officer in charge. Ingersoll directed reductions of officers and enlisted personnel for the Fourth Fleet’s staff and ships, but authorized CruDiv 14 the personnel necessary for the training cruise while keeping the engineering ratings to the absolute minimum. Cleveland’s marine detachment reported for duty to Marine Barracks, Boston as ordered.

Overhaul complete, Cleveland stood out from Boston on 27 March 1946 and proceeded to Newport, Rhode Island, where she joined the rest of CruDiv 14 on 28 March. 1,800 newly commissioned ensigns reported on board Rear Adm. Riggs’ ships the next day—895 were assigned to Cleveland—for four months of duty under instruction. She sailed to Bermuda and New London, Connecticut (15–23 April), took part in exercises with CruDiv 14, and then returned to Newport. On 30 May, she departed for New York before proceeding in company with Columbia, Denver, and Montpelier to Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada and Quebec, Canada, from 12–24 June. On 28 June, Cleveland docked in Naval Shipyard, Philadelphia to disembark the student officers and her remaining officers and crew, and report for pre-inactivation overhaul.

Due to proposed budget cuts, the Navy reassigned CruDiv 14 to the Sixteenth Fleet for inactivation. Despite their relative newness, Cleveland and her sisters demonstrated the limitations inherent in their pre-war design. Extensive modifications adding electronic equipment and anti-aircraft weaponry topside left them overweight, slow, and unstable. Placed in commission in reserve on 24 October 1946, Cleveland was decommissioned into the Atlantic Reserve Fleet on 7 February 1947. Stricken from the Naval Register on 1 March 1959, the Navy sold her to Boston Metals, Baltimore, Md., for scrapping on 18 February 1960.