Brooklyn III (CL-40)

1937–1951

The third U.S. Navy ship named for the city located on the southwestern end of Long Island, N.Y., that was incorporated into New York City in 1898 as one of six boroughs. During the American War of Independence, the British defeated the Americans during the Battle of Long Island (27–30 August 1776) on land that now constitutes Brooklyn. The British victory enabled them to occupy the strategically vital city of New York, however, Gen. George Washington and most of his army escaped to continue the struggle. The New York Navy Yard was established on the area’s waterfront in 1801.

II

(CL-40: displacement 9,700; length 608'4"; beam 61'9"; draft 24'; speed 33.6 knots; complement 868; armament 15 6-inch, 8 5-inch, 8 .50 cal. machine guns; aircraft 4 Curtiss SOC-2 Seagulls; class Brooklyn)

The Brooklyn Cruiser Committee, a special committee of the Brooklyn Chamber and headed by President John E. Ruston, circulated several thousand copies of a petition addressed to Secretary of the Navy Charles F. Adams III: “The name BROOKLYN has been closely associated with military and naval exploits since the time of the American Revolution…Because Brooklyn is an historic place and a major community, it is fitting that a cruiser should bear its name.”

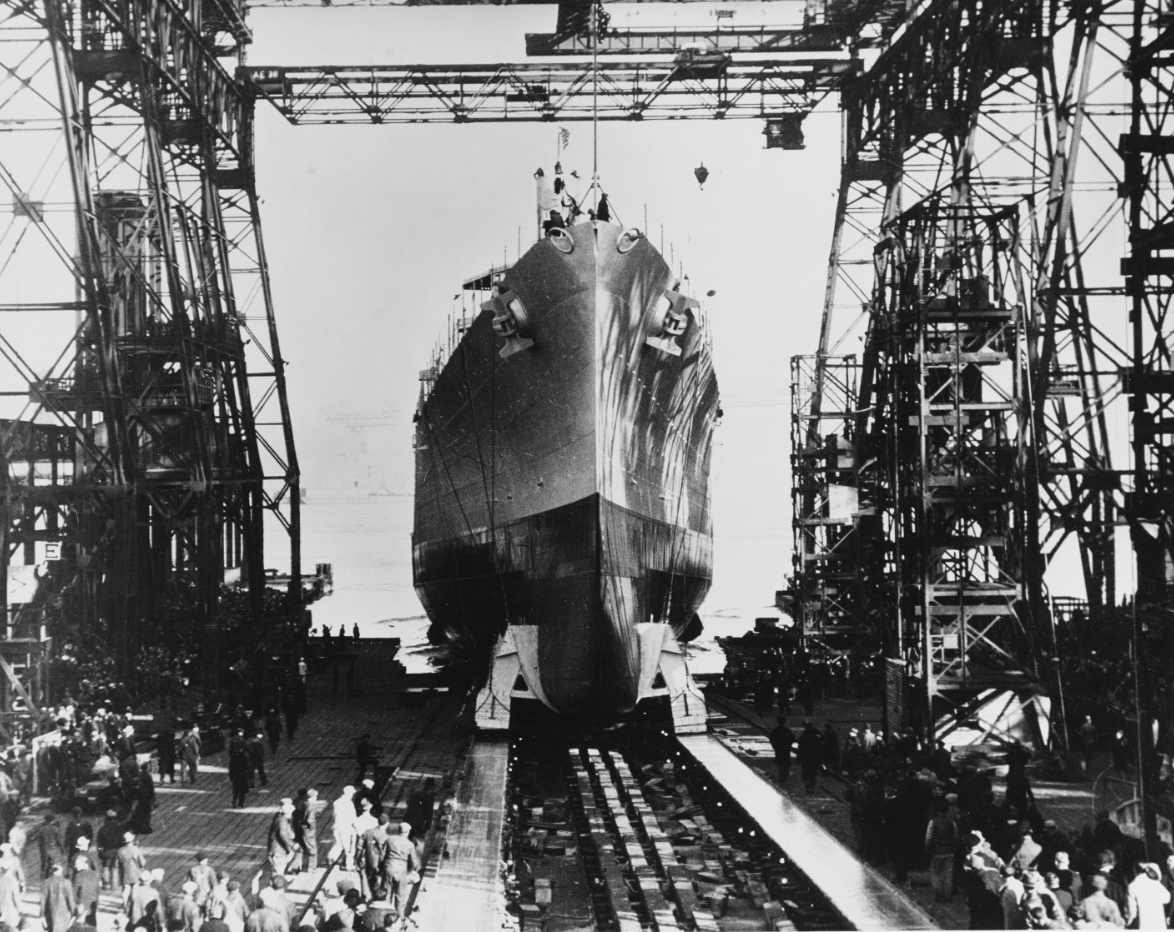

The lead ship of what was to become the Brooklyn class of light cruisers was authorized by an Act of Congress on 13 February 1929; and classified as CL-44 on 5 July 1933. The contract for the ship’s construction was awarded on 3 August 1933; she was assigned the name Brooklyn on 6 September 1933; reclassified to CL-40 on 5 October 1933; and her construction was fittingly allocated to the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on 1 November 1933. The ship was laid down there on 12 March 1935; launched on 30 November 1936; sponsored by Miss. Kathryn J. Lackey, a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and daughter of Rear Adm. Frank R. Lackey, Commander, New York Naval Militia; and commissioned on 30 September 1937, Capt. William D. Brereton Jr., in command.

The nine original Brooklyn class light cruisers also comprised Boise (CL-47), Helena (CL-50), Honolulu (CL-48), Philadelphia (CL-41), Nashville (CL-43), Phoenix (CL-46), St. Louis (CL-49), and Savannah (CL-42). Helena and St. Louis underwent modifications while they were being built and are often considered the separate St. Louis class. The changes included twin 5-inch guns and new higher pressure boilers arranged differently than their predecessors, so that the ships could survive a single hit to their engineering spaces that might otherwise render them dead in the water.

Designed and built under the terms of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty, the Brooklyn class cruisers displaced less than 10,000 tons and were armed with 6-inch guns as their main battery. The ships were designed largely as a response to heavily-armed Japanese cruisers, however, and as a result mounted their 6-inch guns in five triple turrets, three forward and two aft, with Turrets II and IV in super-firing (mounted above Turrets I and III) position. The class was also designed with a flush-deck hull, with a high transom and a built-in aircraft hangar aft.

Following builder’s trials (7–8 and 15–17 December 1937) the Navy considered Brooklyn’s construction completed and accepted her into operational service on 1 January 1938. The ship set out from the New York Navy Yard for her shakedown cruise in the warm waters off Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, on 17 January 1938. On the voyage southward Brooklyn stopped at Hampton Roads, Va. (18–20 January), where the ship began a rewarding fraternity with Cruiser Scouting Squadron (VCS) 8 when she embarked four of the squadron’s Curtiss SOC-2 Seagulls as her Aviation Unit.

The cruiser worked up in Guantánamo Bay (23 January–1 February 1938), and then (2–3 February) obtained tactical data while in Gonaïves Bay, Haiti. She came about for Guantánamo Bay on the 4th, and visited Galveston, Texas (9–14 February), and (16–23 February) New Orleans, La., for leave and liberty call. Brooklyn returned to Hampton Roads on 28 February, where her Aviation Unit disembarked. The ship continued on to the New York Navy Yard and completed unfinished work to prepare for her official trials (2 March–20 July). The light cruiser replaced her SOC-2s with four SOC-3 Seagulls, also from VCS-8, the squadron led by Lt. Herschel A. Smith, when she left the navy yard and stopped at Hampton Roads on 22 July.

Brooklyn began service with Cruiser Division (CruDiv) 8, Rear Adm. Forde A. Todd in command, a long association that continued through the end of her career, as she took part in exercises and gunnery drills off Fort Pond Bay, N.Y. (24 July–4 August 1938). The ship visited Newport, R.I. (4–8 August), and then (11–15 August) returned to Hampton Roads. Brooklyn did not enjoy the brief respite because she next (15–19 August) took part in a series of exercises at the Southern Drill Grounds. The increasingly seasoned ship returned to Hampton Roads and then 23 August–26 September) but required additional work at the New York Navy Yard. The warship stood down the channel and turned her prow northward for a brief (27–29 September) visit to Boston, Mass., but swung around and accomplished further upkeep at the New York Navy Yard (30 September–17 October).

The cruiser wrapped up her yard work and headed for the Caribbean on 17 October 1938, joining CruDiv 8 when she stopped at Hampton Roads on the 18th, and training in Gonaïves Bay (27–28 October and 9–11 November), Guantánamo Bay (29 October–8 November and 12 November–2 December). Her grueling regimen included day spotting and day battle practice, as well as antiaircraft and machine gun practice. Brooklyn came about and on her cruise home put in to Charleston, S.C. (5–8 December) and on the 9th disembarked the Aviation Unit at Norfolk. She then spent the holidays accomplishing voyage repairs and upkeep at the New York Navy Yard (10 December 1938–4 January 1939).

Brooklyn carried out gunnery and operational practices with her consorts Philadelphia and Savannah off Colón in the Panama Canal Zone in the early days of 1939. The ship turned her prow toward those balmy waters in order to prepare for her role in Fleet Problem XX. The annual fleet problems concentrated the Navy’s power to conduct maneuvers on the largest scale and under the most realistic conditions attainable. Fleet Problem XX ranged across the Caribbean and the northeast coast of South America (20–27 February 1939). President Franklin D. Roosevelt observed the problem initially from on board heavy cruiser Houston (CA-30), transferred to battleship Pennsylvania (BB-38), and then returned to Houston to watch the final exercises, and the chief executive’s presence led to the maneuvers becoming unusually publicized.

Brooklyn lay to at Hampton Roads on her southerly voyage (5–7 January 1939), and then (10–13 January) operated in Gonaïves Bay, where she launched and recovered her four embarked SOC-3s, and carried out machine gun practice. The ship took part in exercises at Guantánamo Bay (13–16 January), and Gonaïves Bay (21–27 January and 8–13 February), and completed upkeep alongside repair ship Vestal (AR-4) at Guantánamo Bay on the 28th. Brooklyn gave her crew a much needed break and visited Port of Spain, Trinidad (16–19 February), and then plunged into Fleet Problem XX off Culebra Island, P.R., and Guantánamo Bay. The ship fueled from oiler Brazos (AO-2) on 1 March, fired in support of Fleet Landing Exercise No. 5 on the 4th, and trained at Gonaïves Bay (12–31 March) and Guantánamo Bay (1–8 April).

Following the problem, Brooklyn turned northward and reached the New York Navy Yard on the 12th, where she completed an interim drydocking (17–27 April 1939). The ship floated free and on the 29th crossed to the Hudson River and took part in the opening of the New York World’s Fair on 30 April. An estimated 206,000 people attended the gala on what turned out to be a very hot Sunday. Brooklyn enjoyed that pleasant interlude until 17 May, and then returned to the New York Navy Yard.

While submarine Squalus (SS-192) completed a trial dive about six miles off the Isle of Shoals at 0740 on 23 May 1939, her main engine air induction valve failed and water poured into the boat’s after engine room. The submarine sank stern first to the bottom, coming to rest keel down in 60 fathoms (240 feet) of water. The disaster trapped and killed 26 men in the flooded after portion of the boat. Thirty-two crewmen and one civilian remained alive in the forward compartments of the submarine. The survivors sent up a marker buoy and then began releasing red smoke bombs to the surface in an attempt to signal their distress.

Sculpin (SS-191), sent to the area later that morning, spotted a smoke bomb at 1241 and marked the spot with a buoy. Additional vessels joined her later that day including harbor tug Penacook (YT-6) and ocean tug Wandank (AT-26), and Coast Guard vessels No. 158, No. 409, and No. 991. Divers and submarine experts, including the Experimental Diving Unit from Washington, DC, also converged on the location. In addition, Adm. Harold R. Stark, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), ordered Brooklyn to come about and rush to the scene to render assistance.

During this preparatory period, the 32 survivors below spent a cold night trapped inside Squalus and began to suffer from the effects of chlorine gas released from the battery compartment. At 1014 the following morning, after submarine rescue ship Falcon (ASR-2) reached the area, a Navy diver determined that a salvage operation was possible. At 1130, Falcon began lowering the newly developed McCann rescue chamber (a revised version of a diving bell invented by Cmdr. Charles B. Momsen) and at 1247 established direct contact with the trapped crew. Over the next six hours, they brought up 25 survivors in three trips by the rescue chamber. Brooklyn in the meantime that tragic day reached the area and gave invaluable aid while acting in the capacity of a base ship. After men untangled cables, the fourth trip finally rescued the last seven survivors just after midnight at 0025 on 25 May. A fifth and final descent by the rescue chamber confirmed that no one else survived in the aft torpedo room. Four divers, MMC William Badders, BMC Orson L. Crandall, MEC James H. MacDonald, and TM1 John Mihalowski, each received the Medal of Honor for their extraordinary efforts to rescue the survivors.

Over the next three months, determined salvage operations passed cables underneath the submarine’s hull and attached pontoons on each side of the boat. After blowing the pontoons full of air, Squalus grounded twice before she rose to the surface and was taken under tow into the Portsmouth Navy Yard, N.H., on 13 September. Following an investigation of the engine room compartments, the boat was decommissioned on 15 November, and on 9 February 1940 she was renamed Sailfish (SS-192).

Brooklyn in the intervening time completed her humanitarian assignment and steamed to Hampton Roads (3–4 June 1939). The following day she stood down the channel and turned southward, passed through the Panama Canal, and joined the Pacific Fleet at San Pedro, Calif., on 18 June. From there, on the 30th, the ship continued northward and celebrated Independence Day while also participating (1–17 July) in the Golden Gate International Exposition, which commemorated the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge and the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, and was held at Treasure Island. Brooklyn then resumed her northward journey and took part in Fleet Week at Portland, Ore. (22–31 July).

The cruiser swung around southward and trained in southern Californian waters. She completed work at San Pedro (6–21 and 24–28 August, and 1–4 and 7–26 September), and cruised off Santa Rosa Island in the Channel Islands (21–24 August), San Clemente Island (28 August–1 September), and Santa Barbara (4–7 September). Shortly thereafter (3 October 1939–3 January 1940), she accomplished three months of work at the Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash.

The ship headed south and took part in Army-Navy amphibious maneuvers off Monterey, Calif., early in the New Year (8–14 January 1940). Brooklyn next (15 January–18 March) tackled a regimen of exercises that included stepping-up her crew’s gunnery training, and the men also received instruction in handling casualties and making battle damage repairs under simulated battle conditions. Brooklyn accomplished some work at the Mare Island Navy Yard at Vallejo, Calif. (19–22 March), and then steamed in to Fleet Problem XXI (1 April–17 May), which consisted of two separate phases around the Hawaiian Islands and Eastern Pacific. The cruiser joined the fleet at San Pedro on the 23rd, and on 2 April set out from Long Beach for Hawaiian waters. Brooklyn lay to initially (10–15 April) at Lāhainā Roads, a roadstead between Maui, Lāna‘i, Moloka‘I, and Kaho‘olawe, T.H., that the Navy often used as an anchorage during such maneuvers. From there she sortied for the problem, returned briefly (24–25 April) to Lāhainā Roads, stopped at Pearl Harbor at Oahu the following day, and then resumed the problem. Brooklyn stood in to Pearl Harbor on 14 May, and two days later anchored off Lāhainā Roads. The ship required some work after the problem and made for the Puget Sound Navy Yard, which included entering a dry dock (26–27 May).

Following that grueling schedule, she trained along the West Coast. Brooklyn turned southward and reached Long Beach (30 May–5 June 1940) and (5–7 June) San Diego, before turning westward toward the Hawaiian Islands to conduct battle readiness and training operations with the other ships of CruDiv 8, Philadelphia (flagship), Nashville, and Savannah. Brooklyn trained in those waters with stops for fuel, supplies, and upkeep at Lāhainā Roads (13–30 June and 5–16 and 19–22 August) and Pearl Harbor (1 July–5 August, 17–19 August, and 23 August–7 September).

In particular, Brooklyn held the Light Cruiser 5ʺ/25 Caliber Armament Broadside Gunnery School (17–21 June and 29 June–3 August 1940). At times, the ship hosted gun crews not only from Boise, Honolulu, Nashville, Philadelphia, Phoenix, and Savannah, but also from aircraft carriers Enterprise (CV-6), Lexington (CV-2), Saratoga (CV-3), and Yorktown (CV-5).

“It is considered that this school was well planned and efficiently conducted,” Rear Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, Commander, Cruisers, Battle Force, United States Fleet, reported to Adm. Stark on 19 August 1940. “The results of this school are very gratifying.” Kimmel elaborated that the surface firings scored about 22% hits, and during the last two firing weeks the 5-inch guns consistently struck the target sleeves in all forms of practices, except ominously in Antiaircraft Battle Practice G, “against which form of attack (glide bombing) the 5"/25 battery was relatively ineffective.” The machine guns shot well, however, and splashed a radio controlled target drone in flames, apparently with a punctured gas tank, on its first run. The event also marked the first time that those guns shot down a drone flying at an altitude above 10,000 feet. The students tracked the drone at a mean altitude of 12,300 feet and a true speed of 122 knots, and their shooting hit the target at a position angle of 50°, and it caught fire and crashed.

The seas battered Brooklyn and she went alongside Medusa (AR-1) for repairs at Pearl Harbor (27 August–7 September). The cruiser joined other ships at Lāhainā Roads (7–19 September and 30 September–4 October) and Pearl Harbor (20–30 September and 4–14 October). Brooklyn operated an average of four SOC-3s of VCS-8, Lt. Cmdr. Cameron Briggs in command.

Although the cruiser achieved some of her maintenance and repair goals while alongside Medusa, she needed more extensive work and turned her prow eastward for the mainland. The ship stayed (20 October–5 November) at Long Beach near Terminal Island Naval Dry Docks, which was under construction, and completed an availability at the Mare Island Navy Yard (6 November–1 December). Brooklyn stood down the channel and anchored off Wilson Cove, San Clemente Island (2–3 December). She then (3–6 December) returned to Long Beach, and from there steamed (6–12 December) on to Pearl Harbor, where she trained at sea (16–20 December 1940) and returned in time for the holidays.

When Japanese aggression had increasingly threatened the Pacific Rim in 1938, a committee under Rear Adm. Arthur J. Hepburn, commandant of the Twelfth Naval District, had investigated possible naval base sites on the coasts of the United States, its territories, and possessions. The Hepburn Board, as it became known, ranked Midway Island as a strategically vital bastion, and recommended expanding the defenses there. Ships deployed the Third Defense Battalion of marines (Lt. Col. Robert H. Pepper, USMC) to the island, and Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Savannah, together with stores issue ship Antares (AKS-3), reached Midway with the balance of the battalion on 13 February 1941.

As war with the Japanese loomed the United States also expanded its naval presence in the Pacific and sought closer ties with prospective allies. Rear Adm. John H. Newton, Commander Cruisers Scouting Force, broke his flag in Chicago (CA-29) in command of a composite squadron that set out from Pearl Harbor with little fanfare or advanced planning on a voyage to the south Pacific on 3 March 1941. “I never could quite figure that [the purpose of the cruise] out,” Capt. Bernhard H. Bieri Jr., her commanding officer, observed, “unless they sort of timed it with the adoption of the signing of the Lend-Lease Act. They wanted to let the Australians know that they weren’t being left out on the limb, I suppose.” On 11 March the U.S. Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act; which, in particular, changed the “cash and carry” provisions of the Neutrality Act of 1939 to permit the transfer of munitions to the Allies.

Chicago sailed in company with Portland (CA-33), Brooklyn and Savannah, and the ships of Destroyer Division (DesRon) 5: Case (DD-370), Cassin (DD-372), Clark (DD-361), Conyngham (DD-371), Cummings (DD-365), Downes (DD-375), Reid (DD-369), Shaw (DD-373), and Tucker (DD-374), and oiler Sangamon (AO-28). Savannah’s crew entered the Ancient Order of the Deep when the ship crossed the equator at 166°17'W, on 7 March 1941. The squadron hove to without warning off Pago Pago, Samoa, and surprised Capt. Laurence Wild, the island’s commandant, when the ships visited that American enclave (9–12 March).

Task Group (TG) 9.2, Capt. Ellis S. Stone in command, and consisting of Brooklyn, Savannah, Case, Cummings, Shaw, and Tucker then (17–20 March) visited Auckland, New Zealand. At daylight on the 17th a minesweeper met the American ships off Cape Brett, and her commanding officer boarded Brooklyn and issued instructions for proceeding through the swept channel into the port. The New Zealanders feted their guests in grand style, welcoming them with a cocktail party at the Officers Club, and a dinner hosted by the mayor. The following days became a whirlwind of events that included a civic reception at the town hall, at which Brooklyn deployed a detachment of 250 men, without arms but carrying the national ensign and infantry battalion flag, that marched to a position in front of the speakers stand. In addition, the Royal New Zealand Yacht Club hosted a cocktail party, and men from the task group also attended a state dinner at Grand Hotel, at which Prime Minister Peter Fraser, who arrived by plane, served as the guest of honor; and a dinner for all of the naval aviators hosted by the British Royal Air Force. On the 19th the Americans returned the courtesy as the officers hosted a cocktail party, the guest list gone over by the U.S. consul, naval observer, and liaison officer to insure that they did not miss anyone.

The outpouring of hospitality impressed the Americans. The New Zealanders presented a dance for 500 men on each of the two evenings available. “These were the most beautifully planned and carried out affairs of their kind,” Capt. Stone reflected in his report. “The Town Hall was used and the young ladies who were invited were carefully chosen as Auckland’s best. These were affairs that would have done great credit to any community.” Their hosts also provided a sightseeing trip for a party of 250 on each other two days available, covering the city and its environs, and including a luncheon and refreshments. Another couple of excursions for 500 men each visited Rotorua. The authorities provided buses but citizens graciously offered to drive men about in their cars, and people gathered at railroad stations as the train passed and cheered. In addition, locals often picked-up men on the street and took them to their homes for pot luck meals or sightseeing trips. Following the convivial visit, the ships set out from New Zealand waters and put in to Tahiti in French Polynesia (25–27 March), before returning to Pearl Harbor. Chicago, Portland, Cassin, Clark, Conyngham, Downes, and Reid meanwhile continued separately in to the southern latitudes, and returned to Oahu on 10 April.

“The situation is obviously critical in the Atlantic,” Adm. Stark meanwhile wrote on 4 April 1941. “In my opinion, it is hopeless except as we take strong measures to save it. The effect on the British of sinkings with regard both to the food supply and essential material to carry on the war is getting progressively worse.” Stark ordered a number of ships to set sail from the Pacific Fleet to reinforce the Atlantic Fleet, and by the end of May Yorktown, Idaho (BB-42), Mississippi (BB-41), New Mexico (BB-40), Brooklyn, Nashville, Savannah, and DesRons 8 and 9 passed eastward through the Panama Canal.

On 16 June 1941, President Roosevelt directed the U.S. armed forces to relieve the British garrison of Iceland. The American reinforcements would enable the British to deploy their troops elsewhere, while simultaneously expanding the U.S. forward presence in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Americans launched the operation under great secrecy, before the Icelanders invited them and while the U. S. Senate debated the decision.

The 4,095 men of the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional), Brig. Gen. John Marston VI, USMC, formed the main element of the expeditionary force. Transports Fuller (AP-14), Heywood (AP-12), William P. Biddle (AP-15) brought the Sixth Marines, which comprised the principal strength of the brigade, from the West Coast to Charleston, S.C.—some arrived by rail. There they met the rest of the brigade, boarded their expeditionary ships, and set out on 22 June. Later that day they rendezvoused with Task Force (TF) 19, Rear Adm. David M. LeBreton in command, formed around Arkansas (BB-33), New York (BB-34), Brooklyn, and Nashville.

Capt. James L. Kauffman, Commander, Destroyer Squadron 7, broke his flag in Plunkett (DD-431) in command of the inner screen around the battleships and transports: Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 13, Cmdr. Dennis L. Ryan, Benson (DD-421), Gleaves (DD-423), Mayo (DD-422), and Niblack (DD-424); and DesDiv 14, Cmdr. Fred D. Kirtland, Charles F. Hughes (DD-428), Hilary P. Jones (DD-427), and Lansdale (DD-426). DesDiv 60, Cmdr. John B. Heffernan, formed the outer screen, which steamed 10,000 yards ahead of the task force and comprised Bernadou (DD-153), Buck (DD-420), Ellis (DD-154), Lea (DD-188), and Upshur (DD-144).

Capt. Frank A. Braisted led the Transport Base Force, which counted Fuller, Heywood, Orizaba (AP-24), and William P. Biddle, cargo ships Arcturus (AK-18) and Hamul (AK-30), oiler Salamonie (AO-26), and fleet tug Cherokee (AT-66). The ships stopped at Argentia, Newfoundland, on the 27th to top off with fuel, and three days later stood down the channel for Iceland.

On 1 July 1941 meanwhile, Adm. Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet, organized task forces to further support the defense of Iceland and to escort convoys between the U.S. and that country. TF 1, Rear Adm. LeBreton, was to operate from Narragansett Bay, R.I., and Boston, Mass.; TF 2, Rear Adm. Arthur B. Cook, was to be based at Bermuda and Hampton Roads; TF 3, Rear Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, was to deploy to San Juan, P.R., and Guantánamo Bay; TF 4, Rear Adm. Arthur L. Bristol, was also to operate from Narragansett Bay; and TF 7, Rear Adm. Ferdinand L. Reichmuth, was to be based at Bermuda. Additional forces comprised TF 5, Rear Adm. Richard S. Edwards; TF 6 and TF 8, Rear Adm. Edward D. McWhorter; TF 9, Rear Adm. Randall Jacobs; and TF 10, Maj. Gen. Holland M. Smith, USMC.

The expeditionary force dropped anchors in the outer roadstead of Reykjavik on 7 July, just as the British persuaded the Althing (Icelandic parliament) to agree to the landings, and President Roosevelt announced the agreement to Congress. The marines went ashore the next day. The cargo ships began to unload their supplies at the limited dock space in Reykjavik harbor, and by the evening of 12 July, they had unloaded all of their cargo and all 4,095 marines were ashore. The following day TF 19 and the transports turned back for home. The landings infuriated Großadmiral Erich J.A. Raeder, the German fleet’s commander-in-chief, but the Allies continued to develop bases on Iceland that sustained their operations throughout the war.

On 4 September 1939, Adm. Stark had directed Rear Adm. Alfred W. Johnson, Commander, Atlantic Squadron, to maintain an offshore patrol to report “in confidential system” the movements of all foreign men-of-war approaching or leaving the east coast of the United States and approaching and entering or leaving the Caribbean. U.S. Navy ships were to avoid making a report of foreign men-of-war or suspicious craft, however, on making contact or when in their vicinity to avoid the performance of unneutral service “or creating the impression that an unneutral service is being performed.” The patrol was to extend about 300 miles off the eastern coastline of the United States and along the eastern boundary of the Caribbean. Furthermore, U.S. naval vessels were to report the presence of foreign warships sighted at sea to the district commandant concerned. President Roosevelt subsequently extended the boundaries of the Neutrality Patrol—on more than one occasion.

By the summer of 1941, the Central Atlantic Neutrality Patrol, Rear Adm. Arthur B. Cook, comprised Carrier Division 3, Ranger (CV-4), Wasp (CV-7), and Yorktown, along with Quincy (CA-39), Tuscaloosa (CA-37), Vincennes (CA-44), Wichita (CA-45), and DesRon 11. Rear Adm. H. Kent Hewitt’s CruDiv 8, comprising the four stalwarts of Brooklyn, Nashville, Philadelphia, and Savannah, relieved the four heavy cruisers on 15 July.

TG 2.5, comprising Yorktown, Brooklyn, Eberle (DD-430), Grayson (DD-435), and Roe (DD-418) sailed on a 3,998-mile neutrality patrol from Hampton Roads to Bermuda (30 July–10 August). Yorktown embarked 18 Grumman F4F-3A Wildcats of Fighting Squadron (VF) 5, 18 Douglas SBD-3 Dauntlesses and eight Northrop BT-1s of Bombing Squadron (VB) 5, 17 SBD-3s, one SBD-2, and ten Curtiss SBC-3 Helldivers of Scouting Squadron (VS) 5, and 18 Douglas TBD-1 Devastators of Torpedo Squadron (VT) 5. In addition, her Utility Unit counted one SOC-1, a single Grumman J2F-1 Duck, and a J2F-4, while the ship also stored a BT-1 and a Vought SB2U-1 Vindicator. These planes flew 842.3 hours during the patrol. The task group almost immediately set out again on a 4,064-mile neutrality patrol that concluded at Bermuda (15–27 August), during which the aircraft flew another 1,188.3 hours.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, Brooklyn had reached Bermuda following additional operations. The ship operated three Naval Aircraft Factory SON-1 Seagulls and a solitary SOC-3 of VCS-8 on that momentous day. Three days later she set out again to monitor the Vichy French at Martinique in the West Indies.

As the Battle of France had raged (10 May–25 June 1940), a number of French vessels deployed to Fort-de-France, Martinique, followed by additional ships during the succeeding months. The Allies feared that these vessels could potentially fall into enemy hands, and Rear Adm. John W. Greenslade, Commander, Twelfth Naval District and Pacific-Southern Naval Coastal Frontier, negotiated their fate with French Adm. Georges A.M.J. Robert, High Commissioner for the French Territories in the Western Hemisphere and Commander-in-Chief, Western Atlantic Naval Force. The resulting Robert-Greenslade Agreement (5 August–November 1940) guaranteed the non-belligerency of the French ships and the maintenance of the status quo in terms of French sovereignty over their colonial possessions. An American naval observer was to augment H. Harward Blocker, the U.S. Vice Consul, to ensure French compliance, and to monitor the movement of their vessels. The French could purchase food and other supplies from the United States.

When the war escalated in late 1941, however, U.S. naval authorities feared that some of the French ships might attempt to breakout and return to France. Accordingly, Wasp, Brooklyn, Sterett (DD-407) and Wilson (DD-408) stood out of Grassy Bay, Bermuda, and headed for Martinique (10–15 December 1941). Faulty intelligence gave American planners in Washington the impression that one of the larger Vichy French vessels, armed merchant cruiser Barfleur (X.19), set out to sea. The Americans warned the French that they would sink or capture the auxiliary cruiser unless she returned to port and resumed internment. As it turned out, however, Barfleur had not departed after all but remained in harbor, and the crisis gradually abated.

The voyage did not pass without incident because the Americans believed that U-boats (German submarines) prowled the area. On 14 December 1941, Lt. Wilson M. Coleman and Ens. Delwin A. Liane flew two of Brooklyn’s planes when they spotted what they identified as a U-boat and attacked. An oil slick and debris floated to the surface and the men claimed a kill. The Germans launched Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat) against Allied shipping in U.S. waters, however, they did not deploy their first wave of boats until the 18th—and the submarines required time to cross the Atlantic. Brooklyn’s apparent kill thus eluded the ship and remains a mystery, but the crew understandably operated without actionable intelligence concerning the German movements. Coleman and Liane each received a Commendation Ribbon for their “successful, leading approach to the scene and accurate aim of bombs on the emerging submarine [Coleman],” and “thorough flight training and indoctrination for action…[and] professional capacity of the highest order [Liane].”

Brooklyn and Wilson refueled at Port of Spain on 16 December 1941, a process that delayed their sortie until after dark. Capt. Stone took the submarine peril seriously and decided to stand out to sea at high speed, and to steer irregular and radical changes of course, as soon as the sea room permitted. As the ships approached Boca Grande (the exit channel) watchstanders noted that the garrison turned on the heavy battery of searchlights on Chacachacare Island at intervals of 10–15 minutes, laying light barrages across all of the channels to illuminate any vessels passing through. Stone grew concerned that a searchlight could silhouette the two ships at the wrong moment and expose them to enemy attack, or at the least alert any shadowing submarines that the cruiser and her consort were returning to sea. Brooklyn exchanged recognition signals with the signal control station, and then the captain decided not to request direct darkness for their sortie because, as he reported to Adm. King on the 17th, he did not wish to “affront the intelligence of the local officials.”

“This conclusion was an error that might well have been fatal,” Stone chillingly summarized. Brooklyn and Wilson reached the mid channel and barely cleared the island at 2123 when someone turned on the whole searchlight battery, eerily bathing the ships in light and revealing their presence to any U-boats hunting nearby. Both vessels already steamed at high speed and the captain furthermore concluded that turning back would have given a submarine lurking off the entrance definite information that they intended to return to sea later. The cruiser and destroyer plowed on and emerged to seaward without further problems, but the incident gave their crewmen some tense moments. Brooklyn came about for New York and reached the metropolis on Christmas Eve. The cruiser took a beating battling the unruly Atlantic during her patrols, and completed an availability at the New York Navy Yard through 6 March 1942.

The ship accomplished a shakedown cruise and a series of exercises following her yard work, after which, the Americans dispatched the First Marine Division from the Atlantic to the Pacific to fight the Japanese. Brooklyn loaded some marines and their supplies (7 March–9 April 1942), and then (10–18 April) joined TF 38, also consisting of Texas (BB-35) and 11 destroyers, as they escorted the 17 troopships of Convoy BT 202 from East Coast ports to Colón. Brooklyn then turned her prow northward and left the warm Caribbean waters for the colder North Atlantic as she made for Norfolk, Va. Brooklyn reported her armament as five triple 6-inch gun turrets, eight single 5-inch mounts, four quadruple 1.1-inch antiaircraft mounts, and 12 20 millimeter guns.

From the Tidewater region she sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia (30 April–2 May 1942). Brooklyn then (3–11 May) shaped a course with TF 38, which also counted New York (BB-34) and 14 destroyers, and the task force shepherded British liner Aquitania and six transports in Convoy AT 15, comprising reinforcements for the Allied garrison in Iceland, and part of the U.S. Army’s 34th Infantry Division, from New York to Argentia, Iceland, and on to the British Isles.

British escort aircraft carrier Avenger (D.14) joined the combined convoy at one point. Laid down as Rio Hudson, a C-3-type passenger-cargo vessel, under a Maritime Commission contract (M.C. Hull 59) on 28 November 1939 at Chester, Pa., by the Sun Shipbuilding & Drydock Co.; she was acquired by the Navy on 31 July 1941 for conversion to an “aircraft escort vessel” (BAVG-2), one of the first six such ships built for the United Kingdom under lend-lease. Avenger launched Fairey Swordfish Is of No. 816 Squadron that patrolled around the vulnerable troopships.

Their patrols helped strengthen the convoy’s screen at a crucial moment late on 30 April 1942, when German Type VIIC submarine U-576, Kapitänleutnant Hans-Dieter Heinicke in command, spotted AT 15. The U-boat did not attempt to maneuver into position to attack an ocean liner carrying soldiers, an otherwise lucrative target, because she had fired all of her torpedoes. Nonetheless, Heinicke determinedly surfaced after the ships passed and radioed their position and movement -- as they steered easterly courses at 12 knots -- to Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote (Commander of the Submarines) at his forward headquarters at Kernével in German-occupied France.

One of U-576’s diesels broke down, but Dönitz directed four Type VII U-boats to turn at full speed and form a patrol line across the convoy’s apparent course, due south from Cape Race, Newfoundland. He also tasked U-576 to accomplish repairs and make best speed to reinforce them. Meanwhile on 3 May 1942, the four Allied troopships of Convoy NA 8 set out from Halifax and rendezvoused with AT 15 near Chedabucto Bay, and the combined convoys carried 19,000 troops in all. The Germans repaired U-576’s diesel and Heinicke regained contact on the combined convoys at about the time they rendezvoused, but he reported that the “strong” air patrols compelled him to break contact. Dönitz shifted the other four submarines 30 miles north toward Cape Race, but they failed to intercept the convoys in heavy fog. Brooklyn safely guarded her charges and reached Northern Ireland, followed the next day by Greenock, Scotland. She next (18–27 May) came about and returned to the United States at Norfolk.

Brooklyn trained while en route to Bermuda (25–27 June 1942), and then (24–27 July) completed an availability at the New York Navy Yard. The cruiser set out from the yard (6–8 August) to Halifax, and then (9–17 August) took part in a convoy that crossed the Atlantic from that port to Greenock. The convoy’s escorts detected apparent U-boats more than once but reached Scottish waters, and the cruiser spent a brief sojourn there and on the 27th turned westward for home in Convoy TA 18.

A fire erupted on board transport Wakefield (AP-21), ex-United States Lines passenger liner Manhattan, Cmdr. Harold G. Bradbury, USCG, while she steamed en route from the River Clyde to New York on the evening of 3 September 1942. The flames quickly spread and imperiled the ship. Wakefield steamed in the port column of the formation and swung to port to run before the wind. Her crewmen battled the blaze, threw ready-use ammunition overboard to prevent it from cooking off, secured code room publications, and released patients in sick bay and men held in the brig.

Capt. Francis C. Denebrink, Brooklyn’s foresighted commanding officer, had directed his staff to compile a detailed survivor’s bill so that every crewman would know his part in the event of a disaster. The ship’s company drilled in how to bring survivors on board and provide them with medical attention, food, and berthing, and they responded rapidly to the unfolding crisis. Denebrink served as the officer-in-charge of rescue operations as Brooklyn, Charles F. Hughes (DD-428), Mayo, Madison (DD-425), and Niblack rendered assistance. The calm sea rolled with a slight ground swell, which aided the rescue efforts, and Wakefield ran out her abandon ship ladders.

Hilary P. Jones (DD-427) screened Brooklyn and Mayo from U-boats as the two ships closed to windward to take off passengers. The fires trapped a number of men forward and Mayo slid alongside and took off 247 men (1900–1917). Meanwhile (1907–1927), Brooklyn secured three lines from her forward deck to the after deck of the blazing transport, and her crewmen hauled the survivors on board swiftly and smartly until the cruiser cast off with about 800 men. The survivors on the two ships included a badly-burned officer, and crewmen not needed to man pumps and hoses. Other survivors clambered on board 14 lifeboats and some rafts, to be picked up forthwith by the screening ships. Madison maneuvered into a position approximately 50 yards off Wakefield’s port bow and pulled 80 men from the lifeboats.

Brooklyn moved to rejoin the convoy but flames suddenly leapt up from Wakefield’s superstructure as high as her stacks. “Come alongside same place” the transport signaled the cruiser at 1947, and Denebrink thus eased Brooklyn alongside the transport again to remove the remainder of the crew, while a special salvage detail boarded the ship. Mayo resumed her station in the convoy but another couple of destroyers escorted the cruiser. Wakefield hauled down her colors at 2015, and the determined rescue efforts saved all hands, nearly 1,500 men, many of them civilian workers from construction camps in the British Isles. Brooklyn embarked 1,173 of the survivors, who each received three hot meals and a bunk, and were billeted in 120 compartments around the ship. Niblack also stood by with a salvage party. Brooklyn reached New York in 22½ hours, and smoothly disembarked the survivors in less than an hour.

Coast Guard cutter Campbell (WPG-32) escorted two tugs that took Wakefield in tow on 5 September 1942, and a float plane flew a firefighting team led by Cmdr. Harold J. Burke, USNR, from Naval Air Station Quonset Point, R.I., and landed alongside the stricken ship so that the team could board and control the fires so that the tow could continue. Burke, the former supervisor of the New York City Fire Department’s Marine Division, had pushed for fog nozzles to replace or supplement the traditional solid stream nozzles, a decision that improved firefighting.

The pair of tugs then nudged the ship aground at McNab’s Cove, near Halifax, at 1740 on the 8th. When fire-fighting details arrived alongside to board Wakefield, fires still burned in three holds and in the crew’s quarters on two deck levels. Four days later, the last flames had been extinguished, and the ship was refloated on the 14th. While Wakefield accomplished partial repairs in Halifax harbor, a torrential rainstorm threatened to fill the damaged transport with water and capsize the ship at her berth. Torrents of rain, at times in cloud-burst proportions, poured into the ship and caused her to list heavily. Salvage crews, meanwhile, cut holes in the ship’s sides above the waterline, draining away the water to permit the ship to regain an even keel. The salvagers worked for ten days to clean up the vessel, pump out debris, patch up holes, and prepare her for the voyage to the Boston Navy Yard for complete rebuilding. Wakefield did not return to service until February 1944.

Capt. Denebrink received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal for twice maneuvering his ship alongside the port quarter of the burning transport “with a smart display of seamanship and ship handling…Skillfully directing the activities of other ships participating in the rescue, he enabled assisting vessels to carry out their operations without material damage or loss of life.”

Brooklyn returned to the New York Navy Yard the following day, and completed exercises and an availability at the Norfolk Navy Yard in preparation for her role in Operation Torch—the invasion of Vichy French-held North Africa. The warship recorded her aircraft complement as a pair of SOC-2s and a trio of SON-1s of VCS-8 as she readied for battle.

Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, USA, led the Allied Expeditionary Force as it landed at various points near Casablanca, Morocco, and Oran and Algiers, Algeria. The Allied Naval Force, Adm. Sir Andrew B. Cunningham, RN, comprised three principal parts. The Western Naval Task Force, Rear Adm. Hewitt, was to lands soldiers led by Maj. Gen. George S. Patton Jr., USA, near Casablanca. The Center Naval Task Force, Commodore Thomas H. Troubridge, RN, carried the men of Maj. Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall, USA, to Oran. Rear Adm. Sir Harold M. Burrough, RN, led the Eastern Naval Task Force, which landed troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Charles W. Ryder, USA, at Algiers.

Brooklyn served in TG 34.9, Capt. Robert R.M. Emmet, which transported the 18,783 men of Sub Task Force Brushwood, Maj. Gen. Jonathan W. Anderson, USA. Augusta (CA-31), Brooklyn, Ludlow (DD-438), Rowan (DD-405), Swanson (DD-443), and Wilkes (DD-441) were to provide naval gunfire support to the soldiers of Brushwood. Bristol (DD-453), Boyle (DD-600), Edison (DD-439), Murphy (DD-603), Tillman (DD-641), and Woolsey (DD-437) were to screen against enemy submarines, minesweeper Auk (AM-57) and high speed minesweepers Hogan (DMS-6), Palmer (DMS-5), and Stansbury (DMS-8) would clear mines, while coastal minelayer Miantonomah (CMc-5) was to perform her demanding work. All of these ships were to protect the vessels that carried the troops: transports Ancon (AP-66), Charles Carroll (AP-58), Edward Rutledge (AP-52), Elizabeth C. Stanton (AP-69), Hugh L. Scott (AP-13), Joseph Hewes (AP-50), Joseph T. Dickman (AP-26), Leonard Wood (AP-25), Tasker H. Bliss (AP-42), Thomas Jefferson (AP-60), Thurston (AP-77), and William P. Biddle (AP-15); and cargo ships Arcturus (AK-18), Oberon (AK-56), and Procyon (AK-19).

The invasion force consisted primarily of three regimental landing groups (RLG) from the 7th, 15th, and 30th Infantry Regiments of the 3rd Infantry Division; 1st Battalion of the 67th Armored Regiment; 82nd Reconnaissance Battalion of the 2nd Armored Division; the separate 756th Tank Battalion; and elements of the XII Air Support Command. Sub Task Force Brushwood was to seize Fedala, a fishing town about 15 miles northeast of Casablanca. The soldiers were then to turn south and envelop the area surrounding Casablanca, the main objective in Morocco, and join up with men advancing from Mehdia in the north and Safi in the south.

The Vichy French deployed substantial forces to defend Morocco, including their incomplete battleship Jean Bart, which lay at Casablanca, their principal naval station along the African Atlantic coast, along with light cruiser Primaguet, two flotilla leaders, and as many as seven destroyers, eight sloops, 11 minesweepers, and 11 submarines. They counted more than 150 army and navy planes in their aerial arsenal, though not all were operational. The Casablanca, Fez, Marrakesh, and Meknès Divisions, a mix of European and African troops of varying strength, garrisoned Morocco.

The French fortified the Fedala area with four shore batteries. Batterie Pont Blondin consisted of four 138.6-millimeter guns and was located about three miles northeast of the harbor of Fedala. Batterie du Port consisted of two 100-millimeter guns, and Batterie des Passes of two 75- millimeter guns, both of which lay on Cape Fedala. Finally, the defenders deployed an army antiaircraft battery of four 75-millimeter guns alongside the railroad tracks just south of Fedala. Furthermore, the French heavily fortified Casablanca, and positioned a battery of four guns at Table d’Aukasha, about five miles northeast of Casablanca. Two batteries lay at El Hank, three miles southwest of Casablanca. One consisted of four 194-millimeter guns and the other of four 138.6-millimeter guns. Mounted on central pivots, they could be trained east and west. The garrison positioned antiaircraft batteries, some equipped with searchlights, to protect the harbor of Casablanca from air raids, as well as machine guns at several points throughout the harbor.

Severe problems plagued the landings on 8 November 1942. An unexpected northeastern current and poor visibility caused confusion and disorientation among the transports, and realignment attempts delayed the first landing waves. Once underway, landing craft struggled with high surf and navigational errors that carried many from their assigned landing points. Sub Task Force Brushwood lost a number of landing craft when they scraped rocks in the shallow waters, and the first wave alone lost 57 of its 119 boats. These losses and delays undermined the complex plans for Brushwood, as assault troops compensated for missed targets by starting their assigned operation from their landing points or improvised new missions on the spot.

In addition, the attackers lost the element of surprise as early as 0210, when Batterie Pont Blondin reported unidentified speedboats. Cape Fedala reported engine noises at 0338 and lights flashing at sea at 0400. Shortly after 0500, French searchlights briefly illuminated landing craft on the beach. Although the French did not react, the landing craft support boats opened fire and extinguished the searchlights at about 0523. Shortly thereafter, shore batteries opened fire on control destroyers lingering off the beaches before shifting to transports and approaching landing craft, and the U.S. ships returned fire.

Batterie Pont Blondin shot 150 138-millimeter rounds by the time U.S. troops began assaulting the perimeter. Despite the difficult start, some 3,500 troops of the 3rd Infantry Division landed by sunrise. Soldiers of the 7th Infantry Regiment’s 1st Battalion Landing Team moved into Fedala before dawn and by 0630 captured the Hotel Miramar, the headquarters of the Axis Armistice Commission. Troops also overran the French battery at the mouth of the Nefifikh River by 0730. A battery at Cape Fedala held out longer even under naval gunfire. Col. William H. Wilbur, USA, a member of Gen. Patton’s staff, delivered a cease-fire proposal to the French at Casablanca, and as Wilbur returned he organized a tank assault that compelled the battery to surrender by noon.

As the fighting continued ashore the French counterattacked in the air and at sea. French planes rose to give battle and some of them began strafing the beaches, initially unopposed by American aircraft. Augusta and Brooklyn opened fire on French shore batteries at 0710 on 8 November 1942. The enemy returned fire and Denebrink maneuvered the ship to dodge the enemy’s salvoes throughout the fighting, and red dye from near misses splashed across the deck. One French barrage soared over Augusta’s deck, missing her by a scant few dozen yards.

As the guns of Fedala fell silent at about 0820, naval spotting planes reported that the French 2ème Escadre Légère (2nd Light Squadron), Contre-Amiral Raymond Gervais de Lafonde in command, valiantly sortied to disrupt the landings off Casablanca. Augusta and Brooklyn received orders to engage the enemy, and by 0843, the two cruisers and their screening destroyers closed the range and opened fire, shooting salvo after salvo at the French ships. Augusta and Brooklyn fired 22 salvos and compelled the French to temporarily disengage and come about for Casablanca at 0855. The French continued to resist and Primaguet sortied with destroyers Albatros (T.06), Brestois (64), and Frondeur (82) and threatened the invaders.

The battle almost became Brooklyn’s last, however, because while she fought the enemy ships French submarine Amazone (Q.161) also maneuvered into an attack position against her, at about 1000 on 8 November 1942. Amazone fired five torpedoes at the cruiser, and dived immediately to elude the inevitable counterattack. Cmdr. George G. Herring Jr., Brooklyn’s executive officer, grew concerned that steering the same track rendered the ship vulnerable to attack and recommended changing course just as the torpedoes sped toward the ship. Herring’s hunch paid off as Brooklyn turned sharply in response to a 30° rudder and avoided the torpedoes when they hurtled past close aboard.

Augusta and Brooklyn changed course again and resuming shooting at their determined opponents at 1027, until the French ships retreated. The pair of American cruisers then returned to their positions to defend landing beaches. The French returned again to the fray and Augusta and Brooklyn engaged destroyer Boulonnais (65) as she attempted to launch torpedoes at the U.S. ships (1100–1120). Brooklyn’s main battery mauled the lightly protected Boulonnais as eight 6-inch shells sliced into her, and the destroyer sank near 33°40'N, 07°34'W, taking at least 13 of the ship’s company with her.

Massachusetts (BB-59) sank French merchant passenger liner Savoie Marseille and cargo ship Ile de Edienruder; Massachusetts and Tuscaloosa sank destroyer Fougueux (83); and various U.S. ships sank Brestois and Frondeur. Carrier-based planes including F4F-4 Wildcats from VFs 9 and 41 and SBD-3 Dauntlesses of VS-41 flying from Ranger sank submarines Amphitrite (Q.159), Oréade (Q.164), and La Psyché (Q.174); Dauntlesses and Grumman TBF-1 Avengers of Escort-Scouting Squadron (VGS) 27) launched from aircraft escort vessel Suwannee (AVG-27) and sank submarine Sidi-Ferruch (Q.181), merchant passenger liner Porthos, cargo ship Lipari, and tanker Ouessant.

Massachusetts and bombing and strafing runs by naval aircraft including Wildcats from VF-41 damaged Jean Bart; U.S. ships hit submarine Le Tonnant (Q.172); Dauntlesses and TBF-1s of VGS-29 operating from Santee (ACV-29) struck submarine Méduse (NN.5); and American planes damaged Primaguet, destroyer leader Milan, and destroyers Albatros and L’Alcyon (49). Submarine Herring (SS-233) damaged French cargo ship Ville du Havre off Morocco near 33°34'N, 07°52'W. The opponents also dueled in the air and Wildcats from VF-41 fought French Dewoitine D.520s and U.S.-built Hawk 75As of Groupes de Chasse I/5 and II/5.

Despite Brooklyn’s narrow brush with death she did not escape the battle unscathed that morning. A French light caliber shell struck Brooklyn’s main deck near No. 1 5-inch antiaircraft gun and ricocheted into the sea without detonating. Splinters wounded seven men: Lt. Howard B. Haisch, DC, ARM2c John S. Wall, GM3 William F. Proudfoot, S2c Leonard M. Hottendorf, USNR, AS Floyd R. Howard, AS Gerard J. Trojan, and S2c Erril L. Rooks.

A French plane strafed the ship the following morning, 9 November 1942. The attacker flew quickly toward Brooklyn and her lookouts did not identify the type as it passed over the ship, though onlookers believed that a 20-millimeter round struck the cruiser, thus likely indicating a Dewoitine D.520. The shell hit the deck behind a 20-millimeter gun on the forward machine gun platform and wounded three marines manning the gun: Plt. Sgt. Samuel H. Donavan, USMC, Sgt. Floyd W. Burdge, USMC, and Pfc. Anthony E. Kujawinski, USMCR. The ship’s topside battle dressing station treated all ten men for their wounds and they eventually returned to duty—Hottendorf and Rooks gamely remained at their stations and did not report for treatment until the next day.

The French shore batteries furthermore damaged Massachusetts, Wichita, Ludlow, Murphy, and Palmer. In addition, Stansbury struck a mine, and a German aerial torpedo ripped into transport Leedstown (AP-73). American gunnery proved effective though uneconomical because of faulty U.S. rounds, communications errors, cunning French tactics, and when the concussion from Massachusetts’ and some of the other ships’ guns knocked out their own radar systems in the middle of the action. The U.S. forces attained a victory within six hours, however, the French might have significantly set back the amphibious operations by focusing their counterattacks on the transports.

French sloops Commandant Delage, Gracieuse, and Grandiere sortied on the afternoon watch and rescued survivors from the French warships sunk in battle that morning. Gracieuse and Grandiere returned to the scene of the fighting and picked-up more men on 10 November. At 0400 on Armistice Day, 11 November 1942, a cease-fire went into effect.

Brooklyn moored in Casablanca harbor on 17 November 1942. That day she set out for home, and returned from the fighting to Norfolk on the final day of the month. She rounded out the year completing voyage repairs and upkeep at the New York Navy Yard (2 December 1942–4 January 1943). The warship wrapped-up her yard work and helped screen a convoy across the Atlantic to North African waters (4–25 January 1943), and then came about for home. Brooklyn accomplished an availability at the navy yard at Brooklyn (13–25 February), and then (25–27 February) turned her prow northward for Casco Bay, Maine. The ship joined a convoy for Casablanca (5–18 March), and next (26 March–6 April) came about for an availability at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, Pa., into May.

The cruiser helped protect a convoy across the Atlantic, through the Strait of Gibraltar, and in to the Mediterranean to Algeria (10–21 June 1943) in preparation for Operation Husky—the Allied invasion of Sicily. The ship joined the Western Naval Task Force and fought in company with Birmingham (CL-62) as CruDiv 13, part of TF 86 Joss Attack Force, Rear Adm. Richard L. Conolly, who broke his flag in Biscayne (AVP-11), a small seaplane tender fitted out as an amphibious force flagship. The cruisers operated as the main strike elements of TG 86.1, Rear Adm. Laurance T. DuBose, who broke his flag in Brooklyn. The destroyers of DesRon 13, screened the task group, led by the squadron’s flagship, Buck (DD-420), and comprised DesDiv 25: Bristol, Edison, Ludlow, and Woolsey; and DesDiv 26: Nicholson (DD-442), Roe (DD-418), Swanson, and Wilkes. Additional vessels supported them, including a Beach Identification Group comprising Bristol (see above), British submarine Safari (P.211), and submarine chaser PC-546.

These ships were to help 27,650 soldiers land in the sector near Licata (code word Fibula): the 3rd Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott Jr., USA, in command; Combat Command A of the 2nd Armored Division; the 3rd Ranger Battalion; and the 20th and 36th Engineers, part of a Provisional Corps led by Maj. Gen. Geoffrey T. Keyes, USA, of the Seventh Army, Lt. Gen. Patton. Additional troops of the Seventh Army landed elsewhere, as did the British Eighth Army, Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery, to the eastward. British Force Z was to operate to the southward of Sardinia and intercept the Italian fleet in the event that it sortied from western ports in Italy into the Tyrrhenian Sea against the invasion armada, and the Royal Navy’s Force H was to cover the Allied assaults from enemy ships, planes, and submarines that struck from the Ionian Sea.

Allied intelligence specialists analyzed some of the expected enemy defenses and circulated their findings in Information and Intelligence Annex No. 118-43 to Joss Attack Force Operation Plan No. 109-43. “Controlled mine fields,” the annex noted unpromisingly, “are reported to exist off all southern beaches, but the reports are of indeterminate reliability.” A radar installation near Torre di Gaffi on Beach No. 73 contained a Freya early warning radar and two “giant” Würzburg gun laying radars. “They are believed capable of picking up surface vessels,” the analysts reported, “but if aircraft were in their area, they would probably not be engaged in surface watching.” The Germans emplaced these above ground and with limited protection, because sandbags and blast walls would interfere with their operation, but the Allies surmised that their cabins could be “steel and would probably resist small-arms fire.” Enemy soldiers manned weapons pits, machine gun strong-points, and pillboxes near the water’s edge and just inland, backed-up by mortar and artillery batteries deployed in positions where they could zero in on troops landing on the beaches. A railway battery in the port area of Licata “could fire very effectively on Beach 70-A [and Beach 70-B].” Railroad guns emplaced on the port’s mole could also bring their fire down on landing craft approaching Beaches 71, 72, and 73. Furthermore, batteries on Monte Desusino, which rose about 6,000 yards to the northwest of Beach Blue, commanded the beaches and the Gela plain.

Birmingham, Boise, Brooklyn, and Savannah joined the invasion formation at 1100 on 9 July 1943. The wind and sea were making up and rose till a fresh breeze drove some tank landing craft behind the formation. Rear Adm. Conolly reported that the stragglers experienced great difficulty in keeping up with the formation, and many of the troops struggled with seasickness. Off the Maltese island of Gozo, Rear Adm. Hall divided his ships into three columns, with Savannah to the fore. At 1940 Brooklyn, Birmingham, and their escorts joined the Joss formation and were directed to steer directly for a submarine reference vessel at 6 ½ knots made good. Brooklyn, Birmingham, and Biscayne led five columns of landing craft that labored against the heavy seas as they approached shore during the first watch and the mid watch.

Brooklyn, Buck, and Woolsey were to operate in a fire support area just off Licata and support the assault troops on Beach Green. The cruiser launched her Seagulls and as soon as they encountered enough light to see for gunnery spotting at 0445, swung her guns around and silenced the batteries.

Brooklyn opened fire at enemy troops on Monte Sole to the west of Licata at 0641 on 10 July 1943, joined shortly thereafter by Buck. Enemy artillery and mortars shot at the tank landing craft unloading tanks and troops on Beach Red, however, and so Brooklyn shifted her position and fired at those batteries. British gun landing craft LCG-4 moved closer to shore and blasted mortar positions, and Bristol, Edison, Nicholson, and Woolsey laid smoke to cover the landing craft on the beaches. By 0715 the cacophony of fire silenced the enemy guns raining fire on the soldiers struggling to establish the beachhead, and the smoke screens effectively shielded the assault waves. The infantry required armored support and the tank landing craft were ordered “to land regardless of cost.” Further orders directed Brooklyn to fire on medium range targets in the Joss area for ten minutes, starting at 0800. Brooklyn shot 713 6-inch shells at enemy troops and positions throughout the first day of the landings.

The weather was fair with cloud cover over barely a third of the sky on the morning of 11 July 1943, but at 0635 a flight of 12 Italian Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparvieros [Sparrowhawks] roared in toward the transports offshore. The planes dropped a bomb that damaged attack transport Barnett (APA-5), killing seven soldiers and wounding 35 more, and fragments from near misses gashed Joseph T. Dickman (APA-13) and Orizaba.

Heavy surf and the poor beaches impeded the unloading of troops and equipment on the beaches at Gela, and the Italians had damaged the pier the day before. Most of the tanks they managed to land got bogged down in the dunes, and the men ashore thus fought at a tactical disadvantage when the Germans and Italians launched further counterattacks including the 2./Schwere Panzer-Abteilung (Heavy Tank Battalion) 504 -- attached to Panzer-Abteilung 215 -- a company of PzKpfw VI Ausf. E Tiger I heavy tanks. Naval gunfire again supported the soldiers as they repulsed the enemy.

The wind veered toward the north during the afternoon watch. At 1355 a flight of an estimated 35 Junkers Ju 88As attacked the transports. Savannah steamed at the northwestern corner of the area as the bombers approached from an altitude of 9,000 feet. The Luftwaffe planes flew over the cruiser and as they reached their release point, dropped their bombs and throttled their engines to greater speed to escape the battle. Two of the bombs splashed in the churning waters aft of the ship as she maneuvered and a third ahead but all missed, none of them closely.

Another bomb struck U.S. freighter Robert Rowan at 1545, however, and as the Liberty ship was carrying ammunition she exploded with a devastating blast that shook the anchorage. McLanahan (DD-615) attempted to sink Robert Rowan with gunfire to extinguish the flames from the burning vessel, but shallow water frustrated her efforts and the abandoned merchantman would not sink. Navy landing craft and Orizaba, however, rescued all hands: 41-man merchant complement, 32-man Armed Guard, and 348 troops.

The flames from the stricken vessel nonetheless illuminated the area for some time, and facilitated the next attack by Axis planes when they lunged at the ships offshore. Two of their bombs splashed not far from Savannah as she operated on the outer western edge of the transport area during the raid, which she recorded as the “heaviest bombing attack” of the battle. Allied transport planes carried paratroopers in to the fray but they flew through the gathering darkness and the smoke rising from Robert Rowan, which caused confusion among the ships in the roadstead. “As a result,” Savannah sadly noted, “there was much indiscriminate firing. One transport plane was shot down and crashed about two hundred yards from [SAVANNAH], its survivors being rescued by a destroyer.” Enemy bombers roared in over the ships off the Joss beachhead at 2205 and dropped flares and bombs. They missed their targets, but a bomb splashed close aboard Brooklyn and four bombs straddled Birmingham.

Capt. Humbert W. Ziroli, the ship’s commanding officer, afterward received the Legion of Merit for operating Brooklyn “under persistent bombing attacks and well within range of enemy shore artillery in close support of the 3rd Division. Gunfire of his vessel destroyed several positions and shore batteries and contributed in large measure to the success of our forces.”

Enemy air attacks lacerated ships in the crowded waters offshore and CruDiv 13 requested air cover for Brooklyn at 1000 on 13 July 1943. At noon meanwhile, minelayers Keokuk (CM-8), Salem (CM-11), and Weehawken (CM-12) began laying mines to block Axis submarines from attacking the ships off Gela. Poor visibility hampered Brooklyn and Woolsey while they patrolled southward and westward off Licata near 36°57'N, 14°06'E, on the early morning of 14 July 1943. The ships inadvertently entered the minefield and two mines suddenly detonated and damaged the cruiser. The minelayers laid the deadly undersea menaces at some depth, however, and their blast did not seriously affect ships running on the surface. Brooklyn and Woolsey thus survived their harrowing incursion into the minefield.

Brooklyn, Boise, Savannah, and their escorts detached for Algiers at 1500 that afternoon, and reached the port on 16 July 1943. While Norwegian cargo ship Bjørkhaug loaded Italian landmines in the harbor of Algiers that day, one of the mines exploded. The blast effectively destroyed the ship, and inflicted hundreds of casualties on people in the area. The flames threatened British cargo ship Fort Confidence, which carried a load of oil, and Dutch tug Hudson bravely took her in tow out to sea, where the crew beached her to prevent further loss. Savannah stood by to render assistance during the fiery ordeal. Brooklyn nonetheless made repairs and reported that despite the mines, the damage had “not impaired” her fighting efficiency.

The ship thus returned to the fighting just as enemy air activity over the sea areas became negligible by 20 and 21 July 1943. Birmingham and Chicopee (AO-34), meanwhile, were ordered to return to the United States, while Brooklyn joined Boise and Savannah supported the Seventh Army’s advance across Sicily. At one point the Army requested that these cruisers train their 6-inch guns on enemy shore batteries estimated to contain 12-inch guns, but the Navy denied the request. The cruisers nonetheless supported the soldiers whenever possible, but the Germans laid a minefield off Porto Empédocle that compelled the ships to operate further to sea. The long range hampered their shooting, and British monitor Abercrombie (F.109) thus added her 15-inch guns to their firepower on the 14th. The British shot at 14 targets that day alone, including a railway battery at Porto Empédocle. Mines continued to plague the Allies but minesweepers opened a new approach channel to the southward, and Allied Forces Headquarters – Mediterranean (Gen. Eisenhower) at Malta disseminated information regarding enemy minefields, demolition plans, codes, and call signs. The weathered cruiser came about for home (28 July–8 August) and completed an availability until the end of the summer of 1943. Brooklyn then operated two SOC-3s and a pair of SON-1s of VCS-8.

Following Brooklyn’s yard work she shaped a course back to the Mediterranean on 14 September 1943, and on the 22nd reached Algeria, followed by Bizerte, Tunisia, two days later, and the next day turned her prow northward toward Sicilian waters. The Allies in the meantime invaded the Italian mainland and painfully clawed their way up the peninsula, and captured the vital port of Naples on 1 October. As the Allied troops advanced toward the city, the Neapolitans rose against their German and Italian Fascist occupiers during what became the Four Days of Naples (27–30 September). In addition, the Axis scuttled ships in the harbor and wrecked the port, and planted explosives at a number of points. Several time bombs that they planted in the city’s post office detonated on the 7th, killing or wounding more than 100 people including women and children. Brooklyn turned from Sicilian waters for Naples (22–23 October) but thus reached the city at a tense time, and scenes of devastation and poverty cast a pall over her arrival. The ship steamed back-and-forth between Sicily and Naples (27–28 and 28–30 October), and on patrols to Bizerte (2–3 November) and Malta (5–6 November).

Brooklyn next took part in shepherding President Roosevelt to Eureka, a conference with British Prime Minister Winston L.S. Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph V. Stalin at Tehran, Iran. The President and his entourage of key leaders including Adm. King, Gen. George C. Marshall Jr., USA, Chief of Staff, Army, Gen. Henry H. Arnold, USA, Commanding General, Army Air Forces, Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, USA, Chief of Army Service Forces, and a host of aides and members of their party, embarked on board Iowa (BB-61) and, at 0006 on 13 November 1943, set out from Hampton Roads on the first leg of their journey to the conference.

Capt. John L. McCrea, Iowa’s commanding officer, led TG 27.5, which also comprised Cogswell (DD-651), William D. Porter (DD-579), and Young (DD-580). They battled heavy seas at times during the voyage, and Hall (DD-583), Halligan (DD-584), and Macomb (DD-458) relieved Cogswell, William D. Porter, and Young on the 15th. Land-based planes initially covered the ships from above, and they passed-off their charges to Eastern FM-1 Wildcats and TBF-1C Avengers of Composite Squadron (VC) 1 flying from escort aircraft carrier Block Island (CVE-21), which rotated their patrols over the task group. Ellyson (DD-454), Emmons (DD-457), and Rodman (DD-456) relieved Hall, Halligan, and Macomb during the afternoon watch on the 16th. F4F-4s of VF-29 and TBF-1Cs of VC-29 operating from Santee meanwhile took over from Block Island’s aircraft.

Brooklyn, Edison, Trippe (DD-403), and British destroyers Teazer (R.23), Troubridge (R.00), and Tyrian (R.67) in the meantime formed a group led by Rear Adm. Lyal A. Davidson, Commander, CruDiv 8. The ships made speed to rendezvous with the task group and at 1024 on 19 November 1943, Iowa lookouts sighted Brooklyn and her consorts. TG 27.5 joined the new arrivals at 1052, and Davidson assumed command of the combined task group as the vessels swung around to a new course of 045°.

Ellyson, Emmons, and Rodman detached at 2111 as the ships passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, and the following morning at 0715 Iowa reached Mers-el-Kébir near Oran, where the chief executive and his guests went ashore to an airfield at La Senia. President Roosevelt boarded Transport No. 950, a Douglas C-54 Skymaster, for a flight to Tunis, and from there flew on to Cairo, Egypt, and Tehran.

Iowa came about and steamed to Bahia, Brazil. Brooklyn, British light cruiser Sheffield (24), Capt. Charles T. Addis, RN, Edison, Trippe, Teazer, Troubridge, and Tyrian joined the battlewagon at sea. The convoy passed through the Strait of Gibraltar on 21 November 1943, and at about 0540 Sheffield detached from the formation. Ellyson, Emmons, and Rodman relieved Edison, Trippe, Teazer, Troubridge, and Tyrian at 0820 that morning, and the other destroyers turned for Gibraltar. Brooklyn returned to the Mediterranean and spent Christmas at Malta. The British garrison and the islanders had withstood a German and Italian siege and rubble from bombing raids choked the streets, yet they arranged for sightseeing tours. The selfless gesture touched the ship’s company and they hosted a Christmas dinner for Maltese orphans. After the conference Iowa returned President Roosevelt to the United States.

On 22 January 1944 the Allies carried out Operation Shingle—landings by the Anglo-American troops of the U.S. VI Corps, Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas, USA, at Anzio and Nettuno in Italy. The Allies planned Shingle to outflank German defensive positions across the Italian peninsula. Rear Adm. Frank J. Lowry commanded TF 81 from his flagship, Biscayne, charged with the task of landing the troops: Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division; the British 1st Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. W. Ronald C. Penny; the 6615th Ranger Force (1st, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Battalions and 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion), 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, and the British 2nd Special Service Brigade, comprising No. 9 (Army) Commando and No. 43 (Royal Marine) Commando.

Brooklyn joined TG 81.8 Gunfire Support Group for Shingle. Capt. Robert W. Cary, the ship’s commanding officer, led the group from the cruiser, which also included British light cruiser Penelope (97), Capt. George D. Belben, RN, along with the screening destroyers of DesRon 13 led by Capt. Harry Sanders—Edison, Ludlow, Mayo, and Trippe.

Allied minesweepers worked swiftly in the limited time available before the landings on 22 January 1944, and cleared most of the enemy mines from the approaches. The attackers surprised the Germans, a clam sea smoothed the landings, and the troops stormed ashore with minimal casualties. Brooklyn, British light cruisers Orion (85), Penelope (97), and Spartan (95), and their destroyer escorts provided naval gunfire support for the few targets that the soldiers encountered.

Nonetheless, a few mines remained and minesweeper Portent (AM-106) struck one of the lethal devices at 1010 and sank with a loss of 18 men. British fighter-direction ship Palomares also hit a mine and harbor tugs Edenshaw (YT-459) and Evea (YT-458) took her in tow to Naples. The Germans deployed few troops near the beaches and hurled only sporadic artillery fire at the beachhead, and a handful of Luftwaffe planes attacked, one of which dropped a 500-pound bomb that sank infantry landing craft LCI-20. Allied planes flew over 1,200 sorties to seal off the beaches and provide air cover for the disembarking convoys. By nightfall more than 36,000 men, 3,000 vehicles, and an initial stockpile of supplies -- 90 percent of the original assault load -- were ashore with light casualties.

Capt. Cary received a Gold Star in lieu of his fourth award of the Legion of Merit for his “exceptionably meritorious performance of outstanding services” while leading the gunfire support group during the landings.

Cmdr. Charles F. Sell, the navigation officer, received a Commendation Ribbon for his “extreme skill and tireless effort…[as he] maintained an accurate plot of his ship’s position while she proceeded, often at very high speeds, through narrow channels and waters known to be infested with enemy mines.”

TF-81 continued to offload troops and supplies as VI Corps consolidated its beachhead. The Allies nevertheless failed to advance inland decisively, and their inaction enabled the Germans to vigorously pour troops into the area to deter further landings in Italy—and France. Allied planes proved unable to prevent Luftwaffe raids on the beachhead or on the ships offshore, and enemy aircraft pummeled the Anzio roadstead, especially at dusk. German planes broke through Allied air cover and attacked British destroyers Janus (F.53) and Jervis (F.00) with both conventional and guided antiship glide bombs on 23 January. A torpedo or a guided bomb, possibly an FX 1400 [Ruhrstahl X-1], which both sides commonly dubbed Fritz-X, slammed into Janus. The magazine exploded and she broke in half, capsized, and sank. Jervis and British tug Weasel rescued 94 survivors but 158 men went down with their ship. A guided bomb damaged Jervis without inflicting casualties and she withdrew to Naples.

The following day, 24 January 1944, another series of enemy air attacks struck Allied vessels off Anzio. A bomb hit Plunkett (DD-441), killing 53 crew members and forcing her withdrawal. A bomb narrowly missed Prevail (AM-107) but the attack effectively knocked her out of action. A large air raid near dusk sank St. David and killed 96 men, although the British hospital ship was well marked and illuminated for her humanitarian mission. As the Germans stepped up their efforts to contain the landings, Brooklyn grew increasingly critical to Allied naval gunfire support. Enemy planes also attacked the ship and she suffered several near-misses but continued the battle unscathed. The bombers winged off but a mine or a guided bomb ripped open Mayo, killing five sailors and knocking her out of action.

The Germans continued their attempts to seal off the beachhead on the 25th, and Allied ships blasted the enemy to help the hard-pressed soldiers ashore, while minesweepers cleared channels for the naval gunfire support ships to maneuver. Auxiliary motor minesweeper YMS-30 struck a mine and sank while she swept a 1,000-yard channel for the heavier ships, and 17 of her men died. The following day, British tank landing ship LST-422 hit a mine and caught fire. LCI-32 rendered assistance but within minutes also struck a mine and sank, taking 30 men to the bottom with her. Poor weather hampered unloading on 26 January, and the increasing German air raids and VI Corps’ push inland began to minimize naval gunfire’s effectiveness.

The weather cleared and enabled the Allies to resume full unloading on 27 January 1944. “Having landed the Army,” British Adm. Sir John H.D. Cunningham, RN, Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet, commended TF-81, “it now remains to support and supply them.”

German air raids hammered the Allies on 29 January, but a combination of smoke obscuration, antiaircraft fire, Allied air superiority, and newly fielded anti-guided bomb jammers reduced the effectiveness of the Luftwaffe assaults, which failed to halt the flow of men and equipment into the beachhead. During the first ten days of the battle Allied ships recorded 70 red alerts and 32 bombing attacks.

Gen. Lucas finally launched an offensive on 30 January 1944, but by that time, the Germans had also built-up their strength, stopped the advance, and then (7 February–1 March) counterattacked. Their attacks drove the Allies back to a final beachhead defensive line, where artillery and naval gunfire played an important role in repulsing the enemy thrusts. On 9 February Brooklyn fired 580 6-inch rounds against the German troops during the desperate fighting, and although the enemy pushed into the beachhead the Allies held. The ship came about for Algiers to refuel, resupply, and give her exhausted crew some rest.

While she lay at Algiers on 15 February 1944, a man fell overboard between the end lighter and the pier. He appeared unable to swim, and PFC Henry M. Flati, USMC, of the ship’s company, standing sentry on the pier immediately dived in. The yawing lighter nearly crushed both men but Flati defiantly kept his shipmate afloat until others rendered assistance and saved the man, a feat for which the marine afterward received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.

Brooklyn steamed to Palermo, where, on the night of 22 February, a man fell into the water and cried for help. While Coxswain Matthew P. Giordanella, USNR, manned a gig from the ship when he heard the victim call out and dived in through about 15 feet of cold, oily, and debris-filled water. In spite of the darkness and the foul conditions, he located and saved the drowning man, and was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal.