Black Hawk II (Id. No. 2140)

1918-1947

Black Hawk, born Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak in 1767 in the village of Saukenuk (present-day Rock Island, Ill.) on the Rock River. Black Hawk's father Pyesa was the tribal medicine man of the Sauk people. At age 15, Black Hawk accompanied his father on a raid against the Osage. He won approval by killing and scalping his first enemy. The young Black Hawk then tried to establish himself as a war captain by leading other raids. He had limited success until, at age 19, he led 200 men in a battle against the Osage, in which he personally killed five men and one woman. Soon after, he joined his father in a raid against the Cherokee along the Meramec River in Missouri. After Pyesa died from wounds received in the battle, Black Hawk inherited the Sauk medicine bundle which his father had carried, giving him an important role in the tribe. He did not belong to a clan that provided the Sauk with hereditary chiefs. He achieved status through his exploits as a warrior and by leading successful raiding parties.

During the War of 1812, Black Hawk had fought on the side of the British against the U.S., hoping to push white American settlers away from Sauk territory. Later he led a band of Sauk and Fox warriors, known as the “British Band,” against white settlers in Illinois and present-day Wisconsin in the 1832 Black Hawk War. The war stretched from April to August 1832, with a number of battles, skirmishes and massacres on both sides. Black Hawk led his men in another conflict, the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Afterward, the Illinois and Michigan Territory militias caught up with Black Hawk's "British Band" for the final confrontation at Bad Axe. At the mouth of the Bad Axe River, pursuing soldiers, their Indian allies, and a U.S. gunboat killed hundreds of Sauk and Potawatomi men, women and children.

On 27 August 1832, Black Hawk asked to surrender to the Indian agent Joseph Street but was instead taken to Gen. Zachary Taylor. He surrendered to Lt. Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederacy. After the war, Black Hawk lived with the Sauk along the Iowa River and later the Des Moines River near Iowaville. Black Hawk died on 3 October 1838 after two weeks of illness. He was buried on the farm of his friend James Jordan on the north bank of the Des Moines River in Davis County, Iowa.

II

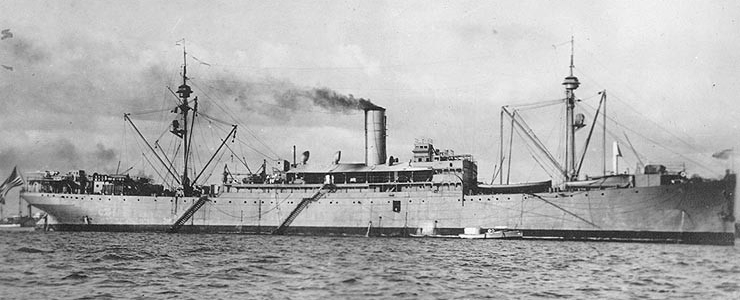

(Id. No. 2140: displacement 13,500; length 404'6"; beam 53'9"; draft 28'5"; speed 13 knots; complement 442; armament 4 5-inch, 1 3-inch)

The steamship Santa Catalina – launched in 1913 by William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Building Co., Philadelphia, Pa. -- was purchased by the Navy on 3 December 1917 and, given the identification number (Id. No.) 2140, was renamed Black Hawk on 26 December, the day after Christmas of 1917. Converted into a tender and repair ship at Fletcher’s Shipyard, Hoboken, N.J., Black Hawk was commissioned there on 15 May 1918, Cmdr. Roscoe C. Bulmer in command.

Black Hawk was assigned as tender and flagship to Mine Squadron One on 22 April 1918, also assigned to the squadron that day were the minelayers Aroostook (Id. No. 1256) and Shawmut (Id. No. 1255). The ship departed New York on 12 June and arrived at President Roads, Boston, Mass., on 14 June. Black Hawk departed Boston with Shawmut, Aroostook, and Saranac (Id. No. 1702) to take station for mining duties in Scotland on 16 June 1918, during the German submarines' activity on the New England coast. Uncompleted work had not delayed them like the other ships of the force, but the trial runs of Shawmut and Aroostook had shown their fuel consumption to be much larger than had been estimated, no data having been available when their conversion was planned. This made their fuel capacity insufficient for the passage to Europe. Indefinite delay, until a tanker could accompany them, was averted by the ships’ captains. By expeditious management the three mine planters, together with Black Hawk, were able to sail in company on 16 June. The only oil hose obtainable quickly was of 4-inch diameter, nearly twice as heavy as that ordinarily used for fueling at sea. The first fueling was done in a gale of wind, and it was a novel undertaking for all concerned. Yet it was successfully accomplished. The second time fueling was done it was easier; and without further noteworthy incident the detachment arrived in Scotland during the evening on 29 June, just before departure on the second excursion to lay the North Sea Mine Barrage.

The Navy Department designated the base at Inverness as Base No. 18, and the one at Invergordon as Base No. 17. The two mine bases were so organized that there were two executive officers, representatives of the commanding officer, in complete charge of all administrative and industrial activities at then: respective bases. Each base was organized with military, industrial, supply, medical, and transportation departments. The work of preparing and outfitting the mine bases was done by contract through the Admiralty. The construction work was done through the controller's department of the Admiralty. Rear Adm. Lewis Clinton-Baker, RN, was the Admiralty's representative in general charge of the work. The intent for all U.S. Naval forces in European Waters was to be self-supporting. In the case of the U.S. Mine Squadron, as a result of the initial supply of mines and regular replenishment by the mine carriers, the force had to draw on the British stocks for very little. With Black Hawk’s arrival this became even less. As of 10 July, Black Hawk served as the flagship for Rear Adm. Joseph Strauss, Commander, Mine Force, Atlantic Fleet. She remained moored off Inverness, and did not take part in minelaying, but her equipment of machine tools and repair material made the Mine Force largely independent in regard to upkeep. Except for docking, U.S. minelayers asked very little of the British in the way of repairs.

After receiving a re-supply of Mk. VI mines, the U.S. squadron got underway on 14 July 1918, and laid 5,395 mines the following day in 4 hours and 22 minutes, the largest number so far laid in a single operation. At 4.20 a.m. on 16 July, while just north of Cromarty Firth, one of the escorting destroyers sheered close in to the squadron’s flagship, San Francisco (Cruiser No. 5), and reported that they were too close inshore. The squadron turned out, stopped and backed, but before headway had been checked Roanoke (Id. No. 1695) and Canonicus (Id. No. 1696) had grounded. Canonicus was able to back off, but attempts to clear Roanoke proved unavailing until she was lightened as much as possible. She came off easily on the following high tide. In light of the fact that neither vessel sustained any damage, the Commander, Mine Force, recommended no further proceedings and the matter was disposed of by Vice Adm. William S. Sims, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces in European Waters in a letter.

The fifth British operation was carried out on 21 July 1918, in Area C. Several days delay was encountered before the fourth U.S. operation on account of again having to wait for mining materiel. The squadron was reported ready to sail on 25 July, but it was necessary to wait four days more for the escorting and supporting forces from the Grand Fleet. The British and U.S. operations had recently been overlapping each other in such a manner that one squadron was out at sea while the other was loading in port. This required keeping a large part of the Grand Fleet at sea almost constantly, the Commander-in-Chief, therefore, desired that the U.S. squadron should wait until the British squadron had again loaded, so that it would only be necessary to send one force to support both squadrons.

The U.S. squadron sailed on 29 July 1918, laying 5,399 mines the following day. The premature explosions, much more numerous than on any of the previous excursions -- approximately 14% of the mines going off – proved most disconcerting. Instead of the explosions decreasing as experience was gained in the assembly and laying of the mines, the percentage had been gradually increasing and then had suddenly jumped to 14% on this excursion. Losses of 3-4% could be tolerated, but this latter figure was prohibitive, and the causes of the explosions had to be determined and eliminated. Due to the large number of premature explosions which occurred in the fourth operation, the Force Commander ordered the suspension of further minelaying operations until the cause of the explosions had been ascertained and corrected. The next excursion, a joint effort by the British and U.S. squadrons began on 8 August. The efforts to cure the premature explosions on this excursion were found even less successful than before; approximately 19% of the mines had exploded. After laying 1,596 mines, the operation was discontinued and the squadron returned to the bases. It was found that the rubber insulation between the copper plates on the firing device caused a slight current in the firing circuit in the direction necessary to operate it. Although the current was in most cases small, there was a possibility that if it were eliminated the mines would then have sufficient stability so as not to explode after they had been planted. In order to carry out the practical part of the experiments after the theoretical tests had been completed at the bases, San Francisco proceeded to the mine field on 12 August. The improvement obtained in this test was sufficient to enable minelaying to be resumed. The squadron sailed on the sixth excursion on 18 August, and the minelaying was completed on the 19th. The squadron got underway for the seventh excursion on 26 August, and stood out toward the minefield. Saranac (Id. No. 1702) broke down shortly after leaving the base and had to return to Inverness with her full cargo of mines. San Francisco and the remaining eight ships, however, continued and carried out the operation. Unfortunately, dense fog was encountered practically throughout the operation; so thick at times that it was impossible for the vessels to see the next ship abeam, distant only 500 yards.

The eighth excursion was intended as a surprise. Neutral nations had not been notified that Area B was dangerous to shipping, and with this knowledge, enemy U-boats were constantly passing through it on their way to the Atlantic. It was accordingly decided not to notify neutrals about the area, but to secretly route all shipping so as to avoid it, with the hope that U-boats might still attempt to use it after it had been mined. In order to prevent the enemy observing the mining while it was in progress, an elaborate patrol was arranged, beginning the day before the operation and continuing until after its completion. British and U.S. mining squadrons rendezvoused off the Orkney Islands on 7 September and proceeded to carry out the operation. The U.S. laid six lines of surface mines across Area B, while the British laid one line of surface mines parallel. This was really the first joint operation carried out by the British and U.S. squadrons. On several previous occasions both squadrons had been at sea at the same time, but had not been working side by side, so as to necessitate appointing one officer to command the expedition. On this occasion, Rear Adm. Joseph Strauss, embarked on board San Francisco, was designated to take general charge of both squadrons while mining was in progress.

In the early morning of 20 September 1918, while the U.S. mining squadron was on its way to the minefield to carry out the ninth excursion, a submarine was sighted off Stronsay Firth. She was immediately attacked with depth charges by the escorting destroyers, and at the same time a smoke screen was laid by both the escort and the minelayers. Shortly afterwards, she was again sighted just ahead of San Francisco, and was again attacked. The squadron proceeded through Westray Firth and then to a position about 6 miles to the northward of the western end of the minefield which was laid on 7 September. In this excursion, 5,520 mines were laid in 3 hours and 50 minutes the record number laid by a minelaying force in a single operation. At the same time, the British squadron laid 1,300 mines in a single line parallel and to the northward of those laid by us. Rear Adm. Strauss, on board San Francisco, was in command of the American minelayers while Rear Adm. Lewis Clinton-Baker, CB, RN, commanded the combined forces. The firing devices had been adjusted and there was a reduction of premature explosions on this excursion, being between 5-6%, a marked improvement.

On 27 September 1918, 5,450 mines were laid, slightly over 4% of which exploded prematurely. Only nine of the mine layers, Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3) having returned to the U.S., took part in this operation. The eleventh operation was carried out on 4 October, again in Area A, and approximately 6% of the mines exploded prematurely. The U.S. mining squadron completed the twelfth excursion on 13 October, losing 4% by premature explosions. Roanoke and Canandaigua (Id. No. 1694) proceeded to Newcastle for docking upon the completion of the operation. Eight days' delay was encountered before the thirteenth and last operation could begin. On account of the sequence of the British and U.S. operations in Areas A and C, it had been impractical to extend the minefields so as to overlap each other. This left a gap between the two areas approximately 6 miles wide. In order to close this, the next excursion was planned to consist of six rows of surface mines to the southward of the gap, continuing with two rows into Area C, so as to complete the four rows which the U.S. squadron had agreed to lay in this area. The first of the winter weather was encountered in this operation, when it was necessary for the squadron to wait one day after having reached the mine field before the sea moderated sufficiently to enable the mines to be laid. Even then the ships were rolling as much as 20º to 30º on each side of the vertical. This provided an excellent test of the mining installations with the result that no difficulties were encountered by any of the ships, either in the stowing of their mines or in the actual planting under such severe conditions. The operation was completed 26 October, having laid 3,760 mines, of which slightly over 4% were lost by premature explosions.

Although the U.S. mining squadron was again ready for the next excursion by 30 October 1918, it was necessary to wait until the British squadron had completed the operation which they had planned before escort could be furnished us. Reliable information indicated that enemy submarines were crossing the eastern portion of Area A, and the British had decided to lay surface mines in this position to the southward of those laid on our first excursion so as to strengthen this part of the field which was the least effectively mined part of the area. Weather conditions, however, prevented them from going out for several days, and, in the meantime, the series of events during the latter part of October and 1 November brought the end of the war into view. Further mining would have been an unnecessary waste of time, effort, and material. The British squadron did not carry out their contemplated operation, nor did the U.S. squadron. With the armistice with Germany on 11 November, came the end of building the North Sea Mine Barrage.

Rear Adm. Strauss summed up the final status of the operation and the results obtained from it as follows: Had it been possible to carry out minelaying operations as fast as the necessary mining material was received and assembled, the U.S. portion of the North Sea barrage could have been completed by the latter part of September 1918. The frequent delays, especially during the latter part of the work, which were principally due to the necessity of awaiting for escort to be supplied by the Grand Fleet, or for the British mine squadron to complete its preparations so as to be able to go out at the same time, prevented the barrage from being completed prior to the signing of the armistice.

Throughout this entire time Black Hawk remained at Inverness. With the war’s end, the mission turned to sweeping the mines laid in the North Sea barrage and clearing those waters enabling safe navigation. On 1 December 1918, the minelayers sailed for the United States, leaving Black Hawk with Patapsco (Id. No. 3475) and Patuxent (Id. No. 2766), as the nucleus for the minesweeping force. Black Hawk remained the flagship and repair ship of this embryo organization, while Patapsco and Patuxent, two powerful tugs, were retained to carry out experiments to ascertain, if possible, some means of sweeping the barrage and to develop the gear that would be required. It had been decided to use Kirkwall, Scotland, in the Orkney Islands, as the primary base for operations given its proximity to the barrage. Arrangements had been completed to obtain from the Admiralty an oil ship, water boat and gasoline boat, also to obtain coal from the British coal barges which were maintained at Kirkwall. Since the transportation facilities from Great Britain to Kirkwall were so inadequate, Base No. 18 was to be used as a receiving base for the constant train of supplies which were required at Kirkwall. Vessels from the U.S. force would transport the supplies between the two bases. Also since the hospital facilities available on Black Hawk were inadequate for the entire force, it was necessary to retain those at Inverness to handle the more serious cases as they occurred.

On 20 April 1919, the first twelve sweepers anchored in Inverness Firth. A few hours later, Rear Adm. Strauss, arrived in Inverness and broke his flag on board Black Hawk. His instructions stated that operations were to begin at the earliest possible moment, and every effort must be made to complete the clearance of the North Sea barrage that year. Everything was in place to commence the first operation by 28 April, but sailing was delayed for 24 hours on account of a heavy snowstorm. The following morning the twelve sweepers which had arrived, accompanied by six submarine chasers, got underway for the barrage, while Black Hawk and the remaining submarine chasers sailed for their new base at Kirkwall. A few hours after Black Hawk had anchored on 29 April, she was joined by Heron (Minesweeper No. 10), Auk (Minesweeper No. 38), Sanderling (Minesweeper No. 37), and Oriole (Minesweeper No. 7), just arriving from the U.S.

The various procedures for communications had been carefully worked out and incorporated in the Minesweeping Orders which had been printed and issued to the force prior to the first operation. In general, all messages which could be transmitted without relaying were to be sent by flag hoist, searchlight, or semaphore. Messages which affected a division, squadron, or the entire force were sent by radiotelephone. Shape signals, consisting of combinations of balls, drums, diamonds, and flags, were also prescribed for the more common signals in connection with passing sweeps and maneuvering. On the whole, the system was highly satisfactory, and after the first few days no difficulties were encountered. The radiotelephone proved highly reliable as well as possessing a high degree of ruggedness, and in only the very severest of accidents was disabled by the explosion of mines. The range of audibility of the telephones for the minesweepers averaged approximately 30 miles. In some cases satisfactory communication was maintained at distances of 50 to 60 miles. On account of the short antenna of the submarine chasers their range of audibility was considerably less, in general, not being more than ten miles. Considerable difficulty was constantly encountered on the submarine chasers on account of the salt-water spray and leaks in their hulls, which caused a great amount of short circuiting in the apparatus. The spark sets on the sweepers, though only 1 kilowatt, proved entirely satisfactory, especially after all sweepers were equipped with audion panels and the flagships with two step amplifiers. Communication between Black Hawk and sweepers at anchor in a Norwegian fjord, 250 miles distant, was executed with ease.

On 2 May 1919, sweepers and submarine chasers completed the first operation and proceeded to Kirkwall. In all 221 American mines had been destroyed, which represented approximately 25% of the total mines which were laid in the areas over which they had swept. By 3 June 1919, the sweepers and submarine chasers were again ready to sail, but a storm delayed their departure until the afternoon of the 5th. That same day, four of the new sweepers, Chewink (Minesweeper No. 39), Flamingo (Minesweeper No. 32), Thrush (Minesweeper No. 32), and Penguin (Minesweeper No. 32), which had been requested by Rear Adm. Strauss upon completion of the first operation, arrived at Kirkwall. Black Hawk began at once the installation of the electrical protective devices which had been sent over on the first sweepers for spares. Group 9 was to be cleared on the third operation. This group, consisting of 5,520 mines, was the largest which had been laid on a single operation. The British had already cleared their single line of mines laid at a depth of 95 feet about 1,000 yards to the northward of our field. Out of the 1,300 British mines originally laid in this line 606 had survived until summer and were accounted for by the British sweepers.

The object in clearing this large group was twofold. On future operations it would shorten the distance that the vessels would have to steam in going back and forth from port and at the same time would reduce the number of mines which might break adrift and menace the ships in the western part of the barrage. Furthermore, this group of mines, although the largest laid, contained only two rows laid at the upper level. It was still desired to avoid as much as possible the chances of being damaged by countermining while experience was being gained. This danger was not, however, so great as had been originally anticipated, and Rear Adm. Strauss had decided to have one division of the minesweepers sweep their section of the field longitudinally in order to

compare this method with the transverse sweeping which had been used up until this time. If the division succeeded in demonstrating that the danger was no greater, our sweeping speed could probably be greatly increased and possibly enough to complete the clearance of the barrage within the year. In order to assess the relative merits of the two methods, Rear Adm. Strauss hoisted his flag on Eider (Minesweeper No. 17) and spent several days on the minefield observing the actual conditions and difficulties encountered. A few days after the operation had begun the admiral returned to Inverness. From what he had seen he was convinced that longitudinal sweeping could be used with equal safety.

On 5 August 1919, Capt. Roscoe C. Bulmer, Commander, Minesweeping Detachment, died on board Black Hawk from injuries received the day before when thrown from an automobile which had skidded. The death of Capt. Bulmer proved a severe loss. His unbounded enthusiasm and cheerfulness, coupled with resolute determination, at times in the face of overwhelming odds, had been invaluable in the early part of the minesweeping when the obstacles and accidents were so discouraging. His body, after being embalmed, was sent to Inverness and then transported to the U.S. for burial.

After seven sweeping operations the North Sea Mine Barrage was declared cleared on 30 September 1919. By the time that the sweeping operations had been completed, all the submarine chasers except two had been sent to Devonport, England, for docking prior to their trans-Atlantic voyage. Black Hawk, accompanied by Oriole, departed Kirkwall, on 1 October. While en route to Devonport, they stopped at Gravesend, England (4 October), to land Rear Adm. Strauss, in order that he might proceed to London. A general railroad strike was in progress at the time. As such, the admiral's automobile, which had been placed on board at Kirkwall, was landed to enable him to proceed to London, and later to Southampton, England, where he embarked upon the steamer Adriatic to return to the U.S. in order to arrange for the disbanding of the force upon its arrival home.

As the repairs at Devonport and Chatham, England, drew to an end, the minesweeping force was divided into two detachments for the trip home, as had been previously decided, with a view of reducing the congestion while the vessels were in harbors and thus enabling them to obtain fuel and water more easily. On 12 October 1919, the destroyer tender Panther and 12 of the submarine chasers sailed from Devonport to Brest, France. They were followed two days later by fourteen of the minesweepers. On 15 October, Black Hawk and the remaining ’sweepers and submarine chasers, except Swan (Minesweeper 34), Auk, S.C.164, S.C.178 and S.C.206, got underway for Brest. The repairs were completed on these latter vessels the day following Black Hawk’s departure, when they got underway. In the meantime three of the vessels which had been sent to Chatham were completed and were on their way to Brest to join the remainder of the detachment. The repairs on Penguin required more time than had been expected, and it was necessary to hold her at the dockyards for several additional days. Although there was plenty of fuel, water, and gasoline available at Brest, considerable difficulty was encountered in getting it on board the vessels. Four days were required before Panther and her detachment of 12 submarine chasers and 14 sweepers could get underway for Lisbon. Black Hawk and the remainder of the sweepers and chasers, however, managed to sail after two days in port (18 October). Panther and her convoy arrived in Lisbon on 20 October, followed by the Black Hawk detachment two days later (22 October). Stopping at Lisbon was intended to break the trip for the submarine chasers given the discomforts aboard those vessels while at sea. The weather, however, was very good and the force could have proceeded directly to the Azores from Brest. After two days spent in port the two detachments, separated by an interval of one day, got underway for Ponta Delgada, Azores.

The weather continued fine for the next leg of the cruise and the two detachments reached the Azores on 27 and 28 October 1919, respectively. The small harbor at Ponta Delgada, was taxed almost to its maximum capacity by the arrival of the 55 vessels in the two detachments. There was much difficulty in obtaining water and provisions and the facilities for supplying water were inadequate. In the meantime Penguin, which had completed her repairs at Chatham, had arrived at the Azores with the tug Concord (S.P. 773), which she was escorting. On the evening of 29 October, Panther and her detachment stood out for Bermuda. Two days later, 30 October, the Black Hawk detachment sailed, and they in turn were followed by Penguin and Concord on 31 October. The excellent weather to the Azores was replaced by gales for the next two weeks. At times the ships were barely able to make headway through the heavy seas. The third day out from the Azores, S.C. 256, which was then in tow of Falcon (Minesweeper No. 28), was destroyed by a fire following a gasoline explosion. Turkey (Minesweeper No. 13) was towed by Panther; Swallow (Minesweeper No. 4) and Auk were oiled at sea by Black Hawk; and several of the submarine chasers were given gasoline at sea. Seagull (Minesweeper No. 30) ran entirely out of oil, and could not operate her radio. The engineer officer, however, managed to connect the radio generator to enable Seagull to call for assistance. Black Hawk, which still had a reserve supply of oil, proceeded to her assistance.

The two detachments straggled in to Bermuda, arriving singly or in groups (9-13 November 1919). The weather made the entering the narrow channels to the inner harbor difficult. By the evening of 15 November, the Panther detachment was ready to sail. The following day the remaining vessels, except Black Hawk, weighed anchor and stood out of the harbor. The weather having been too severe for the dockyard to take Black Hawk alongside the oil dock, it was necessary for her to remain until the 17th in order to get refueled. The two detachments arrived off Tompkinsville [Staten Island], N.Y., on 19 and 20 November, respectively. Shortly after Black Hawk had anchored, Rear Adm. Strauss returned on board and re-hoisted his flag. On 21 November, the vessels shifted berth to the North River anchorage, the sweepers in two columns with the sub chasers tied up alongside.

At 10:00 a.m. 24 November 1919, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, reviewed the North Sea Mine Force from Meredith (Destroyer No. 165). After steaming up one side of the formation they returned on the other side, then the reviewing party went on board Heron to inspect her. The review was followed by a reception for the officers given by the Secretary on board Columbia (Cruiser No. 12). Simultaneously, a luncheon was held for the 2,000 enlisted men at the Astor Hotel. At midnight on 25 November, Rear Adm. Strauss, Commander, Mine Force, Atlantic Fleet, hauled down his flag, and the force disbanded at noon. At that time Black Hawk received orders assigning her to Destroyer Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet, until Panther returned from Europe.

Black Hawk remained at New York through the end of the year, then entered the New York Navy Yard, for the installation of a 12-foot rangefinder, on 8 January 1920. Clearing the yard, she steamed to Cuba for the fleet’s annual winter, arriving at Guacanayabo Bay on 25 January. She then shifted to Guantanamo Bay, on 29 January, before departing for the Canal Zone (C.Z.) on 8 February. She reached Cristóbal, on 11 February and remained there until 16 February, when she went to sea and then made her return to Guantanamo on 26 February. She remained there in port until 26 March, when she shifted to Guacanayabo Bay, arriving the next day. The tender got underway before month’s end and cruised Cuban waters making stops at Guantanamo Bay (2 April), Cienfuegos (3-6 April), then back in to Guacanayabo on 7 April. Moving to Guantanamo Bay on 17 April, she stood there until 25 April, when she cleared bound for New York. Steaming through the Ambrose Channel, she proceeded up the Hudson River, to the North River anchorage on 1 May. After five days, she got underway and steamed to Vera Cruz, Mexico. Arriving on 18 May, she remained there into June. During this time she sent a message to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) on 21 May, stating that the situation stemming from the revolution in Mexico had improved and were “more favorable than they have been for several years.” On 7 June, she received instructions to proceed to Newport when relieved by Des Moines (Cruiser No. 15) and to proceed to Newport to report by dispatch to Commandeer in Chief, Atlantic Fleet and Commander, Destroyer Squadrons, Atlantic Fleet. Getting underway on 15 June, she set a course for New York having received new orders, and reached on the 23rd. Six days later, on 29 June, she entered the New York Navy Yard for maintenance. She cleared the yard on 7 July, and steamed to Newport, R.I.; arriving the next day, she remained there in port until 7 September. During this time, she was re-designated (AD-9) as part of a Navy-wide administrative re-organization on 20 July. Between 7 September and 2 October, she shifted between Newport and Smithtown Bay, R.I. On 2 October, she got underway and proceeded to Hampton Roads, Va. Arriving on 4 October, Black Hawk operated in the waters around the Virginia capes until 27 October. Clearing the Southern Drill Grounds, she steamed to New York, and entered the Navy Yard on 28 October. She remained there through the end of the year undergoing overhaul and modification to include the installation of a torpedo workshop with stowage for torpedoes and air compressors, along with other equipment. During this yard period, she was also permanently assigned as tender for Destroyer Force, Atlantic Fleet, on 4 November.

After spending the holiday season finishing up her modifications, Black Hawk cleared the yard on 4 January 1921. Going to sea, she returned to the Southern Drill Grounds for trials (5 January), then continued on to the Caribbean for fleet winter training, arriving at Guantanamo on 9 January.

After a week at Guantanamo, the tender was dispatched to the Canal Zone. Departing on 16 January 1921, she arrived at Cristóbal, on 19 January, and transited the Panama Canal to Balboa, C.Z. On 22 January, she cleared Balboa, and steamed to Callao, Peru. Arriving on 31 January, she remained there until 5 February and returned to Balboa on the 14th. Passing back through the canal, Black Hawk returned to the Atlantic and continued on to Guantanamo, reaching on 24 February. She remained at Guantanamo until 13 March, then going to sea, she cruised Cuban waters, making several port visits into April. Standing out of Guantanamo on 24 April, she steamed to the New York Navy Yard, docking on 29 April. Undergoing overhaul until 15 June, she cleared the yard that day, and steamed south to undergo trials and training on the Southern Drill Grounds. Arriving on 16 June, she departed the drill grounds on 29 June, and steamed back northward. After passing through the Verrazano Narrows, she steamed up the Hudson River, and moored at North River on 30 June. She remained until 9 July, then proceeded to return to the Southern Drill Grounds (12-21 July), before returning back to the North River anchorage (22 July-1 August). Returning to sea, she steamed to Lynnhaven Roads, via the Southern Drill Grounds (4 August), and remained there until 25 August. Between 26 August and 10 October, she continued to shuttle between the lower Chesapeake Bay and New York with stays of varying length at each. She entered the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 11 October and docked until 8 November. Upon clearing the yard, she steamed directly to New York and entered the navy yard there and remained through the end of the year.

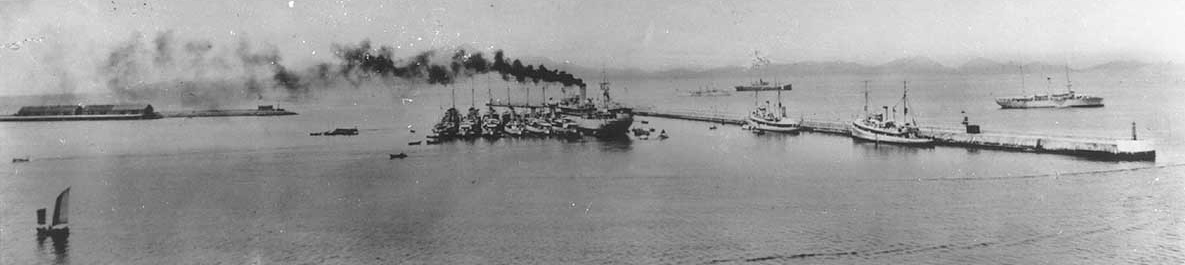

After undocking on 3 January 1922, Black Hawk went to sea and after steaming to the Southern Drill Grounds (4-6 January), she continued on to Guacanayabo Bay. Reaching on 12 January, she joined the fleet for the annual winter training and exercises. Shifting to Guantanamo Bay on 3 February, she remained there until 22 April. Getting underway, she steamed to New York and entered the Navy Yard on 28 April to prepare for distant service. The tender had received orders to serve as the Flagship, Destroyer Squadron, Asiatic Fleet. Clearing the yard on 5 June, she steamed to Newport (6-15 June), then crossed the Atlantic, raising Gibraltar on 26 June. Clearing the British possession on 6 July, she continued on to Marseilles, France (9 July); Malta (12-14 July); Ismailia, Egypt (17-22 July); Aden [Yemen] (27-30 July); Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka] (6-11 August); Singapore (13-18 August), and arrived at her primary base in China at Chefoo [Yantai], on 27 August. She remained there until 30 September, when she got underway to cruise Chinese waters, visiting Shanghai (2-12 October), Amoy [Xiamen] (15-22 October), Hong Kong (23-28 October), before steaming across the South China Sea to Manila, Philippine Islands (P.I.), where she arrived on 30 October. Shifting to the Navy Yard at Cavite, she stood there for almost six months.

Black Hawk resumed operations underway when she cleared Cavite on 7 April 1923, bound for the International Settlement at Shanghai. Reaching on 12 April, she moored off the Bund there until 24 April. Going to sea, she steamed up the Chinese coast to Tsingtao [Qingdao] (8-10 June). After her visit to the port city on the Shantung [Shandong] Peninsula, she proceeded to Chefoo, where she arrived on 11 June. Standing out of Chefoo on 23 July, she moved to Chinwangtao [Qinhuangdao] (24 July-6 August), before returning to Chefoo on 7 August. Again underway on 27 August, she shifted to Darien [Dalian], China (28 August-3 September); before touching at Chefoo, en route to Tsingtao (4-6 September). In response to the Great Kantō earthquake that struck Japan on 1 September, Black Hawk cleared Tsingtao and steamed across the Sea of Japan with relief supplies. She stood at Yokohama, Japan, providing aid (10-27 September).

Departing the Home Islands on 27 September 1923, she steamed to Shanghai (1-12 October), before returning to the Philippines at Olongapo on 16 October. Remaining there until 13 November, she shifted to Manila, that same day and stood there into the spring.

Black Hawk cleared Manila on 12 April 1924 and steamed to Hong Kong, where she spent the next six weeks. Returning to Japan, the flagship visited Nagasaki (26-30 May) and Kagoshima (31 May-7 June), before making her return to China at Shanghai (7-17 June) and Tsingtao (18-27 June), before arriving back at Chefoo on 30 June. She went to sea again on 11 July for a visit to Chinwangtao (12-24 July) before returning to Chefoo (25 July-23 September).

Black Hawk relocated to Tsingtao (24-27 September 1924), then to a lengthy stay off the Bund at Shanghai (29 September-28 November), before returning to Manila on 2 December. As she did the previous year, Black Hawk stood at Manila into the following April.

Going to sea on 18 April 1925, Black Hawk set a course for Amoy. Arriving on 21 April, she weighed anchor on 5 May, and moved on to visit Tsingtao (9 May-3 June), before making her return to Chefoo on 3 June. Standing there until 8 September, Black Hawk made her return to Manila via (Tsingtao (9-15 September) and arriving on 20 September.

Between 9 February and 5 April 1926, Black Hawk departed Manila and moved between Olongapo (9-18 February) and Cavite (18 February-5 April). Clearing the Philippines on 5 April, she transited to Hong Kong (8-11 April) before visiting Shanghai (13 April-10 May) and Tsingtao (11-31 May), en route to Chefoo, where she arrived on 1 June. The flagship would remain here until 4 October. At this same time, China was in the midst of a period of great upheaval. The Kuomintang [Guomindang] Party which constituted the largest part of the Nationalist government, created the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek [Jiang Jieshi] to subjugate the various warlord cliques and their armies to unify the nation under Kuomintang leadership. They launched their Northern Expedition in July and proceeded to fight for the next two years until the warlords bowed to the Kuomintang’s authority in June 1928. In the meantime, Black Hawk cleared Chefoo on 4 October and went to sea to visit Tsingtao (5-19 October) and the International Settlement at Shanghai (21-28 October), en route to her regular seasonal return to the Philippines. She reached Manila on 1 November, and remained there until January.

Getting underway on 31 January 1927, Black Hawk shifted to Olongapo (31 January-3 February) before returning to Manila on the 3rd. She stood out of Manila to make her return to China on 18 April. Three days later, she touched briefly at Amoy before moving on to Shanghai. Reaching on 24 April, she remained there off the Bund until 6 June, when she got underway for Chefoo and arrived on 8 June. She would remain there in port over the next three months. Departing Chefoo on 14 September, she touched at Alacrity Bay (15-16 September) and then continued on to Southeast Asia en route to a return to the Philippines. Her first port visit was to Saigon, Cochin China, French Indochina [Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam] (23-26 September). Continuing on, she moved to Singapore (28 September-1 October). After departing this British possession, the tender moved on to the Netherlands East Indies (N.E.I.) [Indonesia] visiting Batavia [Jakarta], Java (3-9 October), Soerabaja [Surabaya], Java (10-13 October), and Makassar [Ujung Pandang], Celebes (15-17 October). She then proceeded back to the Philippine archipelago touching at Tawi-Tawi (19 October), Zamboanga (20-22 October), and San Fernando (24-27 October), before returning to Manila on 28 October and remaining there through the end of the year.

Black Hawk got underway on 13 February for a brief visit to Olongapo (14-15 February) before returning to Manila. After a month in port, she went to sea and steamed to Hong Kong (23 March-3 April) before visiting other locations along the Chinese coast including Amoy (4-7 April), Magpie Bay (8 April), Samsa Inlet (8-10 April), and Alacrity Bay (12 April), before steaming eastward to the “Land of the Rising Sun” and calling at Kobe, Japan (16-26 April) and Ito Saki, Japan (26-27 April). Returning to Chinese waters, she made landfall and spent a fortnight at Chinwangtao (30 April-14 May), before arriving at Chefoo on 15 May. Remaining in port until 8 July, she got underway and visited Tsingtao (10-12 July) and Shanghai (14-18 July), before returning via Tsingtao (20 July) to Chefoo on the 21st. She continued to operate from there until 18 September, when she sortied to return to Manila, reaching on 25 September. Having returned to her primary base in the Philippines, the tender remained in port well into the next year.

While Black Hawk got underway to visit Olongapo (15-20 February 1929), she largely stood in port until 4 March, when she stood out of Manila Bay bound for Hong Kong. Arriving on 8 March, she remained until the 13th, when she moved on to Amoy (15-24 March). Departing on 24 March, she steamed to Japan for visits to Nagasaki (29 March-10 April) and Yokohama (13-23 April). Returning to China, she spent a month at Tsingtao (27 April-27 May), then arrived back at Chefoo on 28 May. Standing in port until 5 July, she got underway and conducted visits to Tsingtao (6-17 July) and the Bund at Shanghai (20 July-11 August), before returning to Chefoo via Tsingtao (13 August) on 14 August. Clearing Chefoo for the year on 16 September, she made a third visit to Tsingtao (17-23 September) and a second to Shanghai (26 September-2 October), before standing in to Manila on 6 October.

Black Hawk spent much of the first quarter of 1930, shifting to different locations in the Philippines with time at Manila, Olongapo, and Subic Bay. Steaming from Manila on 1 April, she reached Hong Kong on 3 April, remaining there until the 9th. She then proceeded to visit Amoy (9-22 April), Tsingtao (26 April-8 May), and Chinwangtao (11-24 May) before arriving at Chefoo on 24 May and settling in to a period in port. Sortieing from Chefoo on 30 September, she initiated her return to the Philippines via a roundabout route through Southeast Asia. Bypassing French Indochina, she steamed to Singapore (9-15 October), then moved on to the Netherlands East Indies, visiting Batavia (21-27 October), Soerabaja (27-29 October), Buleleng, Bali (2-3 November), and Makassar (4-7 November). Making her return to the Philippine Islands, she called at Tawi-Tawi (9-10 November) and Coron Bay (12-13 November) en route to her return to Manila on 14 November.

Black Hawk again made a visit to Olongapo early in the year (9-12 March 1931), in advance of her departure from Manila for China. Getting underway on 16 April, she reached Shanghai on 21 April. Remaining there until 3 May, she continued to move up the coast visiting Tsingtao (5-14 May), Chefoo (15-16 May), and Chinwangtao (17 May-1 June), before returning to Chefoo on 2 June. Operating from Chefoo, Black Hawk made visits to Tsingtao (9-13 September) and Shanghai (15-17 September and 23-24 September). Finally, standing out from Chefoo on 17 October, she made her return to Manila via Shanghai (20 October-2 November) and standing in to Manila Bay on 6 November.

On 4 February 1932, Black Hawk steamed in haste for Shanghai and arrived on 9 February. She would spend more than three months off the Bund. The flagship’s lengthy visit coincided with the Shanghai Incident (28 January-3 March) which saw fighting around the city between China and Japan. Though a cease-fire was eventually brokered by the League of Nations, tensions remained around the International Settlement. She finally steamed out of the Yangtze River on 23 May, bound for Chefoo she arrived two days later and began her period in port. Just over four months later on 3 October, she cleared Chefoo, for a return to Shanghai (5-25 October), before visits to Amoy (28-31 October) and Hong Kong (2-9 November). Departing the Chinese coast, she returned to Manila, where she remained through the end of the year with the exception of a 10-day period at Olongapo (5-15 December).

Still in port at Manila on 1 January 1933, Black Hawk went to sea on 11 April and proceeded to Hong Kong. Arriving on 13 April, she remained until the 17th, when she departed for Amoy (18-24 April) and Shanghai (27 April-16 May) before arriving at Chefoo for her period in port on 18 May. Remaining until 5 October, she cleared that same day for Shanghai (7-20 October) before proceeding to Hong Kong (24 October-1 November) en route to Manila, where she arrived on 4 November.

Black Hawk sortied on 9 April 1934 and steamed to Japan for visits to Yokohama (16-25 April) and Kobe (26 April-3 May). Making her annual return to Chinese waters, she arrived at Shanghai on 6 May, and after ten days, she cleared the Bund, and steamed to Chefoo. Arriving on 18 May, she began her in port period tending to the ships of DesDiv 5 until 5 October. After visits to Tsingtao (6-7 October); Shanghai (9-28 October); Amoy (31 October-4 November); and Hong Kong (6-14 November), she returned to the Philippines and entered the Navy Yard at Cavite on 16 November. With her maintenance period completed she shifted to Manila, where she remained into the next year.

Black Hawk got underway on 14 April 1935 and set a course for Shanghai. Arriving on 18 April, she remained until 30 April, when she departed for Kobe (3-17 May). After her visit to Japan, she made her return to China, and re-establishing her summer residence at Chefoo on 19 May. She remained until 21 September, when she cleared Chefoo en route to Hong Kong (26 September-14 October) and Louraine Bay (16-22 October) before returning to Saigon (24 October-2 November). Upon departing French Indochina, the tender, steamed on an easterly course and raised Manila on 6 November.

Going to sea from Manila on 13 April 1936, Black Hawk called at Olongapo (17-20 April) in advance of her return to China. She arrived at Shanghai on 24 April and remained until 13 May. She then proceeded to Chefoo, where she stood in port for two weeks (15-29 May), then moved to Chinwangtao (30 May-5 June), before returning to Chefoo and her summer time in port on 6 June. She stood there tending to her attached destroyer division until 14 October, when she departed for Shanghai. Lying off the Bund from 16 October until 2 November, she cleared the mouth of the Yangtze and steamed to Hong Kong (5-11 November). Departing this British Far Eastern possession, she steamed to the other, arriving at Singapore on 16 November. After a week’s visit, she got underway on 23 November and steaming directly to the Philippines, she stood in to Manila on 28 November.

Black Hawk cleared Manila on 5 April 1937 and arrived at Hong Kong on 8 April. Leaving the next day, she moved on to Shanghai (12 April-6 May). The tender then continued on to Chefoo where she arrived on the 8th to perform her tender duties. She got underway again on 2 July to visit Chinwangtao (2-11 July). During her time away from Chefoo, Japanese and Chinese forces clashed at the Marco Polo Bridge outside Peiping [Beijing] on 7 July. The incident sparked the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The ship returned to Chefoo and remained there until 8 November, when she set a course for Tsingtao (9-10 November) en route to Shanghai. Arriving at the International Settlement on Armistice Day, she moored on “Man of War Row” amidst the fighting between the Chinese and Japanese forces in and around the city. After a week, she departed on 18 November, and steamed back in to Manila on 26 November for the winter.

Black Hawk departed Manila on 1 April 1938 and steamed to Hong Kong for a two-day visit (4-6 April). Bound for a return to Manila, she arrived on 10 April, and then departed the next day for two months cruising the Philippine archipelago. Clearing the island of Mindanao on 14 June, she steamed to Bangkok, Thailand. Arriving on 21 June, she remained a week before charting a course eastward, reaching Manila on 2 July. She stood at Manila until 15 July, then went to sea to return to China. After a time at Hong Kong (18-20 July), she shifted to Chefoo (24 July-15 September). Moving on to Shanghai (19-28 September), she returned to Manila (4-9 October), before again cruising the islands in the southern part of the archipelago (10-20 October). With the cruise completed, she returned to Manila on 22 October.

Black Hawk returned to cruising the Philippines when she departed Manila on 10 April 1939. Returning to the city on 22 May, she remained there until 3 June, when she sortied for China. Arriving at Hong Kong on the 5th, she stood there until 7 June, then continued on to Shanghai (11-16 June), before arriving at Chefoo on 18 June. After seven weeks in port, the ship got underway for a visit to Shanghai (13-19 August), before making a brief return to Chefoo on 20 August. Departing again that same day, she spent next five weeks cruising the Chinese coast making multiple port visits during that time. Steaming from Chefoo on 29 September, she made her return to the Philippines. Initially arriving at Manila on 5 October, she departed again on 18 October. Cruising the islands south of Manila, she made her return to the city on 2 December, and spent the Christmas and New Year’s holidays in port.

Black Hawk stood out of Manila on 24 April 1940, to make her return to war-ravaged China. Initially visiting the British possession at Hong Kong (29 April- 6 May), she returned to Chefoo (11 May-8 June), before getting underway to visit Tsingtao (9-10 June) and Chinwangtao (12-22 June) before returning to Chefoo on the 23rd. Black Hawk stood there until 20 July, when she departed for Shanghai (22-29 July) and then moved on to Tsingtao (29 July-9 September). Standing out of Tsingtao, she steamed for a return to the Philippines, reaching Olongapo on 15 September. She then spent the next three months cruising Philippine waters until standing in to Manila on 19 December. She remained in port until 15 April 1941 and then spent the succeeding months continuing to patrol the Philippine Islands

Black Hawk, now assigned to DesRon 29, Asiatic Fleet, cleared Manila, and arrived at Balikpapan, Borneo, N.E.I., on 30 November 1941. She got underway on 6 December in compliance with orders from Commander in Chief, Asiatic Fleet, directing her to Batavia, for “supplies and liberty.” She was in company with Whipple (DD-217), Alden (DD-211), Edsall (DD-219), and John D. Edwards (DD-216) as Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 57. With news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December [8 December west of the International Date Line], the tender received orders to change course and proceed to Soerabaja. Arriving on 9 December, she moored and performed repairs to various other ships through December. She received orders on 30 December from Commander in Chief, Asiatic Fleet, to move to Port Darwin [Darwin], Northern Territory, Australia. She departed that day in company with Boise (CL-47), Pope (DD-225), Barker (DD-213), and the tanker George C. Henry (later Victoria, AO-46).

Black Hawk arrived at Port Darwin, on 6 January 1942 and soon took Peary (DD-226) and Heron (AVP-2) alongside for repairs to damage suffered in the Japanese bombing of Cavite Navy Yard (8 December) and in the Straits of Molucca (31 December), respectively. On 20 January, Black Hawk was designated as flagship, Commander, Base Force, at Port Darwin. On 3 February, in compliance with order from Commander, Task Force (TF) 5, she departed on 3 February, bound for Tjilatjap [Chilachap], Java, N.E.I. Reaching her destination on 10 February, she would serve as a repair ship. Repairs of note include those to Marblehead (CL-12) after she suffered damage in the action at Makassar Strait on 4 February and those required by Whipple after her collision with the Dutch light cruiser HNLMS DeRuyter on 12 February. She was underway again on 20 February, at the direction of Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Southwest Pacific. Bound for Exmouth, Western Australia, Australia, she arrived on 26 February, accompanied by the submarine tender Holland (AS-3), Barker (DD-213), Bulmer (DD-222), and the submarine Stingray (SS-186). While en route on 22 February, she rendezvoused with Pope and John D. Ford (DD-228) at Christmas Island for the purpose of transferring 23 Mk. 8 torpedoes, to the destroyers. Operating in Australian waters (26 February-29 May), Black Hawk departed Exmouth on 2 March and shifted to Fremantle, Western Australia, arriving on 6 March. She departed Fremantle on 10 May, and then moved to Melbourne, Victoria (18-21 May) and Sydney, New South Wales (24-29 May), before leaving Australia bound for the U.S. via Pago Pago, American Samoa (6 June). In company with Parrott (DD-218), she stood in to Pearl Harbor, on 15 June, and reported for duty to Commander Destroyers, Pacific. She was assigned to tender duty, and provided service to 13 destroyers at Pearl Harbor.

Black Hawk departed Pearl Harbor in company with the oiler Ramapo (AO-12), as Task Group (TG) 2.5 on 19 July 1942. Bound for Kodiak, Alaskan Territory, they rendezvoused en route with King (DD-242) on 27 July, and arrived at Kodiak on the 29th. Assigned to tender duty in the territory, she remained there until 4 November 1942, when she departed for San Francisco, Calif. Accompanied by Humphreys (DD-236), she reached San Francisco on 11 November, and that same day entered the United Engineering Co. Ship Yard for repairs and overhaul. Completing her overhaul on 16 March 1943, Black Hawk cleared the yard the next day and returned to Alaskan waters, arriving at Kodiak on 25 March. She departed three days later and shifted to Dutch Harbor, Unalaska, in the Aleutians (30 March-10 April), before proceeding to Adak Island in the Aleutians.

Black Hawk remained at Adak until 21 September 1943, when she accompanied vessels of Task Units (TU) 11, 15, and 16 to Pearl Harbor. Arriving on 30 September, she remained at Pearl Harbor, providing tender service into 1944. Clearing the naval base on 1 February 1944, Black Hawk returned to Adak on 10 February and remained there until 21 March 1945. Following overhaul at Alameda, Calif., she arrived at Pearl Harbor 30 May 1945; remained there until 11 September; and then proceeded to Okinawa to support Allied occupation forces in the western Pacific. Black Hawk served in the Far East tending vessels at Okinawa and in China until 20 May 1946, when she headed home for the last time.

Black Hawk decommissioned on 15 August 1946. Deemed surplus to Navy needs and made available for disposal on 5 September, she was stricken from the Navy list on 25 September. Transferred to the Maritime Commission on 4 September 1947, she was then sold to Kaiser Co. Inc. on 17 March 1948, and then resold that same day to Dulien Steel Products Co., for scrapping.

Black Hawk received one battle star for her service in World War II.

| Commanding Officers | Dates of Command |

| Cmdr. Roscoe C. Bulmer | 15 March 1918 – 5 August 1919 |

| Cmdr. Ellis Lando | 5 August 1919 – 1 October 1919 |

| Cmdr. John Rodgers | 1 October 1919 – 28 November 1919 |

| Capt. Byron A. Long | 28 November 1919 – 22 December 1921 |

| Capt. John W. Timmons | 22 December 1921 – 1 January 1924 |

| Cmdr. Charles T. Hutchins Jr. | 1 January 1924 – 2 September 1925 |

| Cmdr. Adolphus Staton | 2 September 1925 – 21 March 1926 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Eugene M. Woodson | 21 March 1926 – 24 July 1926 |

| Cmdr. Guy E. Baker | 24 July 1926 – 23 July 1927 |

| Cmdr. Randall Jacobs | 23 July 1927 – 15 January 1929 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Carroll W. Hamill | 15 January 1929 – 27 February 1929 |

| Lt. Cmdr. George B. Wilson | 27 February 1929 – 11 March 1929 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Lee C. Carey | 11 March 1929 – 15 October 1929 |

| Capt. Aubrey K. Shoup | 15 October 1929 – 1 July 1930 |

| Cmdr. Aquilla G. Dibrell | 1 July 1930 – 8 September 1930 |

| Cmdr. Walter H. Lassing | 8 September 1930 – 5 July 1931 |

| Capt. William P. Gaddis | 5 July 1931 – 7 May 1932 |

| Cmdr. Rufus W. Mathewson | 7 May 1932 – 28 July 1934 |

| Cmdr. Kinchen L. Hill | 28 July 1934 – 12 November 1935 |

| Cmdr. John H. Everson | 12 November 1935 – 20 March 1936 |

| Cmdr. Jay K. Esler | 20 March 1936 – 9 February 1937 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Chester M. Holton | 9 February 1937 – 10 March 1937 |

| Cmdr. Jay K. Esler | 10 March 1937 – 13 April 1937 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Chester M. Holton | 13 April 1937 – 17 April 1937 |

| Cmdr. Howard D. Bode | 17 April 1937 – 19 March 1938 |

| Cmdr. Willard E. Cheadle | 19 March 1938 – 11 March 1939 |

| Cmdr. Marshall B. Arnold | 11 March 1939 – 5 June 1940 |

| Cmdr. George L. Harriss | 5 June 1940 – 13 January 1943 |

| Cmdr. Edward H. McMenemy | 13 January 1943 – 13 May 1944 |

| Cmdr. Charles J. Marshall | 13 May 1944 – 17 August 1945 |

| Cmdr. Francis W. Beard | 17 August 1945 – 15 August 1946 |

Christopher B. Havern Sr.

20 February 2018