An evergreen shrub native to Texas and known for its purple blossoms.

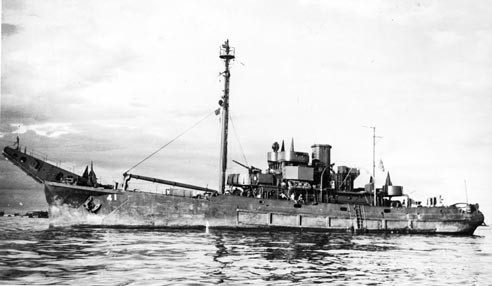

The wooden hulled net tender YN-60 was laid down on 19 December 1942 at Everett, Wash., by the Everett Pacific Shipbuilders and Dry Dock Co.; named Baretta on 17 March 1943; launched on 9 October 1943; sponsored by Miss Evelyn Jaramo, the 11-year old daughter of a shipfitter at the building yard; reclassified as a net-laying ship, AN-41, on 20 January 1944; and commissioned alongside Pier "A" at her builder's yard on 18 March 1944, Lt. Comdr. Ravenel L. Collins, DE-V(G), in command.

After fitting out in the Seattle, Wash., area, Baretta cleared Naval Station, Seattle, late in the afternoon watch on 6 May 1944 for San Pedro, Calif., which she reached early on the afternoon of 12 May, mooring at the Net Dock. The ship then conducted her shakedown training out of San Pedro into late May, operating from the Naval Operating Base there.

Following post-shakedown repairs, Baretta, assigned to Service Squadron Six, sailed for the Territory of Hawaii (T.H.) on the morning of 20 June 1944. En route, on the afternoon of 27 June, she overtook her sister ship Spicewood (AN-53) and the old tug (ex-minesweeper) Bobolink (ATO-131), then accompanied them for the remainder of the voyage. The ships reached Pearl Harbor on 29 June.

Baretta remained at Pearl, temporarily attached to the 14th Naval District, alternating between the Section Base at Bishops Point and the Navy Yard, into the third week of July 1944. Detached from district command on 20 July and given orders to report to Commander, Service Force, Pacific, for duty "in the forward areas," the ship spent the remainder of the month of July loading mooring and net gear.

Taking her departure from Oahu on the morning of 8 August 1944 in convoy as part of Task Group (TG) 32.6, Baretta set course for the Solomon Islands. During the voyage, In company with the internal combustion engine repair ship Cebu (ARG-6) and Cliffrose (AN-42), the ship arrived at her destination on the morning of 26 August. She remained at Gavutu Harbor, off Guadalcanal, until the forenoon watch on 4 September, when she got underway to rejoin TG 32.6. Taking her position in the convoy later that same morning, Baretta set course for the Palau Islands.

As the convoy neared its destination, alerts and submarine contacts increased, until the ships reached Peleliu on 18 September 1944, three days after the initial landings there. After lying-to, 1,000 yards off Orange Beach, awaiting instructions, Baretta escorted the tank landing ship LST-661 to Kossol Passage, arriving there on 22 September. There, she moored alongside the U.S. Army Transport Sea Runner and embarked the men and loaded the equipment of the Fleet Post Office slated to be established on Peleliu. Underway to return to that island on 24 September, she reached her destination later in the day, transferring her people and gear to the attack transport Leonard Wood (APA-12) the next morning.

Over the next four months, Baretta maintained net defenses in the Palaus. On 26 September 1944, she worked on the moorings in Saipan Town Harbor, Angaur, until a Japanese air raid interrupted her labors. Later that same day, worsening seas rendered the anchorage unsafe. In the afternoon of 29 September, she received a request for help from tank landing craft LCT-867 that had fouled a mine with her anchor. Baretta proceeded to the scene and stood by, ready for the worst, while the tank landing craft cut her anchor cable and then cleared the area.

Baretta resumed her work on moorings but, on 1 October 1944, worsening weather forced her to stop. In the midst of a moderate gale the next morning, LCT-404 requested assistance for a mechanized landing craft (LCM) whose ramp had jammed in the down position. Baretta answered the call, towing the craft alongside stern first, and then into the lee of the island off Red Beach. When the LCM's ramp had been freed, raised, and secured, it proceeded under her own power to Red Beach. Later that day, Baretta retrieved an unmanned vehicle and personnel landing craft (LCVP) adrift in a seaway. She took the landing craft in tow, but the line parted and heavy seas prevented further attempts at salvage. At 1022 on 4 October, Baretta was lying off Angaur Island when LCT-579 struck a mine 300 yards off shore. Baretta's motor launch sped to the scene with a rescue party and removed 11 shocked and injured men, all found on board, before the damaged tank landing craft plunged to the bottom.

Through the rest of October 1944, Baretta carried out similar multi-faceted operations. Her men carried out repairs on board LCT-774, LCT-862, LCT-925, and LCT-970. Her diving party removed a line fouled in the screws of LCT-925 on 5 October, then performed the same service for LCT-970 two days later. She took soundings preparatory to laying small craft mooring buoys off Purple Beach, Peleliu, on 6 October. She supplied LCT-774 with 300 gallons of fresh water three days later, and capped that day by towing LCT-858 clear of Purple Beach, where the tank landing craft had broached earlier that day and had been unable to free herself from her predicament unaided. On 18 October, Baretta assisted Grapple (ARS-7) in recovering the broached LCT-129 at Orange Beach, Peleliu, and stood ready to assist that salvage vessel on subsequent days. Still later in the month, Baretta began the work of fueling LCVPs and LCMs from various transports and cargo vessels in the vicinity as the situation required.

While the threat of Japanese air raids occasionally caused temporary suspension of work, the weather, too, caused many an anxious moment. On 7 November 1944, while Baretta lay-to off Purple Beach, Peleliu, sheets of rain reduced visibility to 500 yards, then to the length of a football field, then to zero by the end of the first dog watch. By noon, her men had seen that the buoy boat tethered astern was sinking. The line parted as the ship got underway to run eastward before the storm. Baretta made no attempt to recover it due to the seaway and the heavy rain. The ship spent much of the following day underway as well, finally returning to Purple Beach on the morning of the 9th, the tempest having subsided.

For much of November 19844, Baretta continued her work, at Saipan Town Harbor, Angaur, and off the Blue and Purple Beaches, and in Barnum Bay. She interspersed those operations with upkeep alongside Cliffrose and taking on or discharging gear alongside the net cargo ship Zebra (AKN-5) or fueling from the gasoline tanker Kern (ex-Rappahannock) (AOG-2). She spent much of December thus engaged, occasionally interrupting her work for an air raid alert or (as on 5 December 1944) the threat of a Japanese surface operation. In early December, Baretta assisted LCT-858 clear of a broach off Purple Beach on the 7th, then towed LST-225 free of that strand the next day.

After transferring gear to a storage barge in Barnum Bay on 3 January 1945, Baretta sailed to Kossol Passage later the same day, in company with the cargo ship Kenmore (AK-221) and Nemasket (AOG-10), screened by the destroyer escort Bebas (DE-10). The little convoy arrived at its destination the next morning. The net-laying ship then briefly returned to her maintenance work in a succession of places, beginning on 5 January, off Orange Beach, at Saipan Town Harbor, at Schonian Harbor and, finally, Barnum Bay, until she got underway on the afternoon of 10 January for the Caroline Islands, in company with Spangler (DE-969). A submarine contact enlivened the voyage to their destination, and it almost reached an uneventful conclusion at 1021 on 12 January, but a submarine alert soon after Baretta stood in to the anchorage sent her crew hastening to general quarters, where the men stayed until after she secured alongside Cliffrose at 1147. Later that day, Baretta sailed for the Marshalls in company with Cliffrose, the light minelayer Montgomery (DM-17) and the submarine chaser SC-1363.

At 0913 on 16 January 1945, an engine room fire broke out on board Baretta, stopping the ship. Although her crew extinguished the blaze within an hour (1025), the mishap had rendered the ship's engines temporarily out of commission, compelling Cliffrose to tow her sister ship for the remainder of the voyage to Eniwetok. Although Baretta's engineers had been able to coax 70 turns out of her number one shaft on the 20th, the ship reached her destination at the end of Cliffrose's towline on 21 January, mooring alongside her sister ship a little less than an hour into the afternoon watch. Baretta spent five days under temporary repair alongside Oahu (ARG-5).

Underway for Oahu under her own power on 26 January 1945, once more in company with Cliffrose, Baretta reached Pearl Harbor on 8 February for an availability. Ultimately clearing Pearl on 16 April, the net-laying ship proceeded to Eniwetok, and thence to Guam, arriving at Apra Harbor at 1420 on 3 May. After discharging her remaining cargo, 12 "nun type" radar screen detection buoys, to the medium landing ship LSM-164 during the forenoon watch the following day, Baretta reported for duty to the Commander, Forward Area, Pacific, for temporary duty.

Shortly afterward, she received a dispatch from that command ordering her to sail for Ulithi on 5 May 1945, where she was to relieve the net-laying ship Viburnum (AN-57) that had been damaged by a mine explosion on 28 October of the previous year and had consequently been- performing only limited harbor work ever since. Baretta reached Ulithi on 7 May, and, for the next three weeks, operated on the main net line there, "upending, repairing, and replacing the anti-torpedo panels," which, at the outset, were "in bad shape." She devised a new method of handling the nets, which both saved time and reduced the possibility of damage to the buoys. "The new overlap method," according to her war diarist, "proved quick and safe."

Baretta toiled at Ulithi into late June 1945, retrieving, rigging, and laying anti-torpedo net moorings, evolutions rendered necessary by recent breaks in the system. While thus engaged, she received orders to report to the Port Director, Ulithi, for onward routing to Okinawa. Consequently, the net-laying ship got underway for the Ryukyus on 28 June in 16-ship convoy UOK-31, consisting of six tank landing ships, six merchantmen and two other naval auxiliaries, shepherded by McCoy Reynolds (DE-440). Detached from UOK-31 on 4 July when five miles west of the southern tip of Okinawa, Baretta proceeded independently to Kerama Retto where she relieved Terebinth (AN-59).

On 6 July 1945, Baretta, in company with Stagbush (AN-69) and Winterberry (AN-56), began removing the southern entrance net to the anchorage at Kerama Retto, and carried out that task over succeeding days. Baretta transported two 100-foot sections of the net out to sea where she sank them with small arms fire on 9 July, and by 13 July, all of the net had been removed and loaded unto tank landing craft for transfer to Buckner Bay, Okinawa, with the exception of the sections disposed of by Baretta. That task completed, the three net-laying ships then recovered the anchor legs of the fleet telephone moorings in Kerama Retto for transfer to Buckner Bay. Before proceeding to that place, however, Baretta assisted LCT-466 that, laden with 130 tons of net gear on board, had lost her ramp and assumed a 10-degree list to starboard. Baretta built a wooden jury ramp, repaired the tank landing craft's leaking starboard ballast tank and shifted the cargo to port, making her ready for sea.

The next afternoon, Baretta received orders to "prepare to execute Typhoon Plan William." An hour and a half into the second dog watch on 15 July 1945, in company with Stagbush and Winterberry, she set course for the anchorage at Unten Ko, off northeastern Okinawa, arriving off the entrance to that body of water in the middle of the morning watch on the 18th. The three net-laying ships proceeded into the inner anchorage, transiting a winding channel "protected from wind and sea by wooded hillsides." As Baretta's chronicler noted with satisfaction: "A better typhoon haven for any direction blow would be hard to find." The ships rode out the storm until a half hour before the end of the forenoon watch on 21 July, when seven net-laying ships and eight motor minesweepers (YMS) stood out for Buckner Bay, arriving there at the end of the second dog watch the same day.

Following upkeep and logistics in the wake of the typhoon, Baretta, along with Stagbush and Winterberry, laid the fleet telephone moorings in berth L-8 of Buckner Bay on 27-28 July 1945. Six days of maintenance ensued, after which time the passage of another typhoon forced the ships to get underway again to seek shelter from a big "blow." Underway at 0700 on 1 August for Katena Ko, a typhoon anchorage two miles south of Unten Ko, in company with six other net-laying ships, Baretta "went chasing up the east coast of Okinawa" driven by a "strong" breeze from the northeast (Beaufort Scale 6) and a State 4 sea. The ship rolled 30 degrees to a side before reaching relatively tranquil waters, the ship's war diarist recording with obvious relief: "Having once rounded the northern tip of Okinawa the elements calmed and at 1700 we proceeded to the inner anchorage of Katena Ko with little difficulty." She "rode out the blow" (that reached a maximum Beaufort Scale reading of 7) "anchored bow and stern with two YMS's alongside."

That storm having now passed, salvage work lay ahead for Baretta. On 4 August 1945, she received orders to return to Unten Ko in company with Catclaw (AN-60) to salvage a Japanese midget submarine discovered there, lying intact in 35 feet of water in the midst of three similar undersea craft damaged beyond repair. "All had been sunk," Baretta's chronicler explains, "at their midget sub base by our aircraft two months previous-" Divers from Baretta and the coastal minesweeper Reaper (AMc-89) worked wire lifting straps around the submersible, while the former positioned herself for the hoist. After all preparations had been made, and Catclaw likewise positioned herself, what came next, as described in Baretta's laconic war diary: "The AN-60 [Catclaw] then came alongside and having made her two wires fast in a similar manner, all four winches heaved together and up came the 50-ton submarine." Keeping the boat afloat, however, proved a difficult matter, as "floating required the attaching of 12 empty gas drums to the stern of the submarine which persisted in sinking even though all apparent leaks and ballast were removed." Baretta turned her temperamental charge over to Reaper for disposition.

While Baretta's routine proved just that for the next few days, elsewhere momentous events were occurring. In stunning succession, atomic bombs leveled Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 and Nagasaki on 9 August, convincing the Japanese of the futility that lay in further resistance and prolonging hostilities. While the enemy contemplated surrender in the face of those cataclysmic events, Baretta had set course for Buckner Bay, clearing Unten Ko at the start of the forenoon watch on 11 August in company with LST-494, LSM-465, and YMS-468. The ships reached their destination for logistics, provisions, fuel, and water ten hours later. Her upkeep completed by the 12th, the net-laying ship began maintenance work on the T-9 line that lay south of the entrance gate at Buckner Bay.

At 1700 on the afternoon of 14 August 1945, all minecraft received orders "to be prepared for departure on one hour's notice." At 0800 the next morning, Baretta was proceeding to the net line when she received word by radio notifying "...all ships present that Japan's surrender had been officially accepted and all offensive action was to cease." Upon arrival at the net line an hour later, Lt. Martin Mackey, D-V(G), Baretta's commanding officer, mustered all hands on the fantail where, as the ship's chronicler notes, the men received "the official word on peace." Lt. Mackey read a prayer of thanks "and all hands gave the Lord's Prayer together," after which he declared "Holiday routine."

The stilling of the guns and engines of war, however, proved only a prequel to what lay ahead. To prepare for the occupation of Japan, paths through the mine-strewn approaches to the ports of debarkation had to be cleared. Such an effort required the support of ships like Baretta. At 1820 on 4 September 1945, two days after the surrender ceremony on board battleship Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay, the net-laying ship proceeded to Unten Ko to load navigational gear to be used in marking the Kii Suido channel off the port of Wakayama.

Finding the Coast Guard lighthouse tender Woodbine (WAGL-289) "working the storage area" ahead of her, however, Baretta thus received "a day in which we could put the men ashore for recreation, the first in over a month." Okinawa, though, "three months after its capitulation," the ship's diarist observes, possessed " ...practically nothing in the way of recreation for small craft. A strip of beach for drinking beer, a highly mythical substance, is the place designated for rest and play." The unclean state of the water did not permit swimming, but enlisted hiking and recreation parties received permission to explore the main island of Okinawa. "Our three trips to this Unten Ko anchorage," Baretta's Pepys writes, "have best served us for morale purposes."

Baretta loaded 20 5,000-pound "clump" anchors and 20 "class #2 navigational buoys" at Unten Ko before clearing those waters for Buckner Bay to pick up additional equipment the following day. Soon after loading that material, however, she received word that sailing times for all ships involved in the first phase of the occupation of Wakayama had been advanced 24 hours to 1200 on 8 September 1945. That that change would impose hardships on the vessels preparing for that movement at an accelerated pace is evident from Baretta's wry recorder: "This meant fuel, water, provisions, pay records, three job orders and forty more shots of chain would have to be picked up and the convoy conference squeezed in before noon. We were satisfied with all but fuel, fresh provisions, and the job orders."

Baretta stood out of Buckner Bay at 1150 on 8 September 1945, and sailed with TG 52.6, the Wakayama Sweep Group, setting course for Kii Suido. The convoy formed two hours later and set off for Japan. At noon on 11 September, the ships reached their destination, and, a Japanese pilot and interpreter being embarked in the guide ship, the light minelayer Gwin (DM-33), four minesweepers streamed their gear and stood into Wakayama. Baretta proceeded astern of the second sweep unit, while in her wake steamed two hospital ships and a 5th Fleet task group. Her voyage to the former enemy's homeland completed, she anchored an hour into the second dog watch on the 11th.

The dawn of 12 September 1945 revealed "many curious natives" lining the beach a half-mile away from the ships' anchorage, who "gaped at us, the first strange intruders." That same morning, light minelayer Thomas E. Fraser (DM-24) and Stagbush began laying channel buoys. Baretta later joined them, planting buoys at three mile intervals. Each of the net-laying ships received a "well done" from Thomas E. Fraser. Anchored at Wakanoura Wan the following day, Baretta fueled three motor minesweepers, then topped off her own tanks from the oiler Suamico (AO-49).

On the evening of 16 September 1945, weather reports warned of an approaching typhoon. At 0920 on the 17th, "all ships received orders to be ready to get underway on 30 minutes notice." Increasing her scope of chain to 60 fathoms, Baretta awaited the onslaught, the wind increasing to force 6 by 1800. Dragging anchor, infantry landing craft LCI-814 fouled the net layer's bow a little less than an hour later. Baretta backed down and veered chain to 90 fathoms, enabling the landing craft to free herself. During the night, the wind velocity increased until, one hour into the mid watch on the 18th, Baretta clocked it at between 81 and 89 knots. "Continually dragging" motor minesweepers and infantry landing craft in her vicinity contrasted to the Baretta's handling well in the storm, the bow anchor holding. By 0730, the wind quieted to 30 knots, and Baretta headed for the lee of Awajii Island to avoid heavy swells coming from the northeast. After the storm abated that afternoon, Baretta returned to Wakanoura Wan, the devastation wreaked by the typhoon very much in evidence: three tank landing ships and a motor minesweeper lay stranded on the northern beaches of the anchorage, and a Catalina flying boat had been sunk.

On 19 September 1945, the net-laying ship replanted a mid-channel radar buoy in Kii Suido which the typhoon had dragged some 500 yards away from its original position. Observers on board Baretta noted that the 15 other mid-channel buoys had "remained well enough in position," necessitating only one being replanted - that task fell to her sister ship Stagbush. More work lay ahead a few days later, when, on 22 September, while entering Kii Suido, the battleship California (BB-44) snagged a channel buoy in her streamed paravanes, dragging it with her some 25 miles before she anchored. Baretta recovered the buoy and received just compensation for her trouble. "Thirty cases of beer from the BB," writes Baretta's diarist, "was considered good reward for the job." She replanted the recovered navigational aid the following day.

On 25 September 1945, the first liberty parties were permitted ashore on southern Honshu. One of Baretta's sailors noted the varying Japanese reactions to the occupiers: "Some men bowed or saluted while others glared with obvious hostility. Young girls hurried away at our approach and hid themselves. The elder women seemed less attracted by us than anyone. The children were at first shy but by the second day were running about yelling and waving at us as if we were participants in a big parade or carnival. Bartering sprung up after a slow first day when the Japanese didn't know how safe their goods were."

Baretta rode out one more typhoon in the Wakanoura area before she shifted to Nagoya. She cleared Kii Suido on 6 October 1945, running into a strong head wind an hour before the start of the mid watch, the wind-whipped sea high enough for her horns to "dip into green water." Reducing speed to eight knots, the little convoy of six motor minesweepers and the coastal minesweeper Medrick (AMc-203) struggled through the "tail end of the typhoon we had ridden our two nights earlier" before they reached Nagoya late on the afternoon of the 7th. A mix-up in instructions regarding pilotage separated the two units of the task group requiring the second, led by Baretta, to steam outside the channel entrance throughout the night, it deemed inadvisable to attempt passage of those waters without a pilot.

Baretta spent the rest of the year 1945 laying and replanting buoys around the Ryukyus and in the Japanese home islands. She departed Japanese waters four days after Christmas of 1945 and proceeded, via Eniwetok and Pearl Harbor, to the California coast. Baretta underwent pre-inactivation overhaul at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard and was decommissioned there on 4 April 1946. Baretta was stricken from the List of Naval Vessels on 8 May 1946.

Sources conflict, however, on her post-U.S. Navy service after that point. One tells of her acquisition by Mr. O. Clive Webster, of Bermuda, on 20 January 1947, but another states that she was transferred to the Maritime Commission on 24 January 1947.

Baretta received one battle star for her participation in the occupation of the Southern Palaus in World War II.