Baltimore IV (Cruiser No. 3)

1890-1937

The largest city in Maryland and one of the major seaports of the United States.

IV

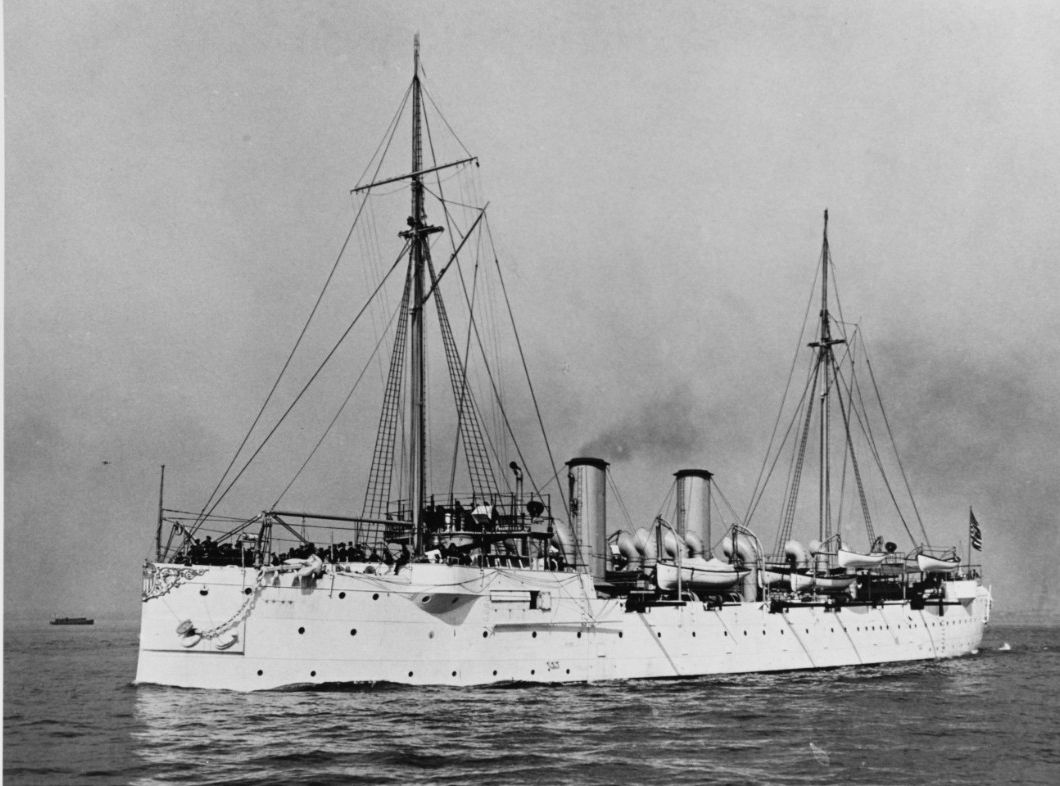

(Cruiser No. 3: displacement 4,413; length 335'; beam 48'8"; draft 20'6"; speed 20.1 knots; complement 386; armament 4 8-inch, 6 6-inch; class Baltimore)

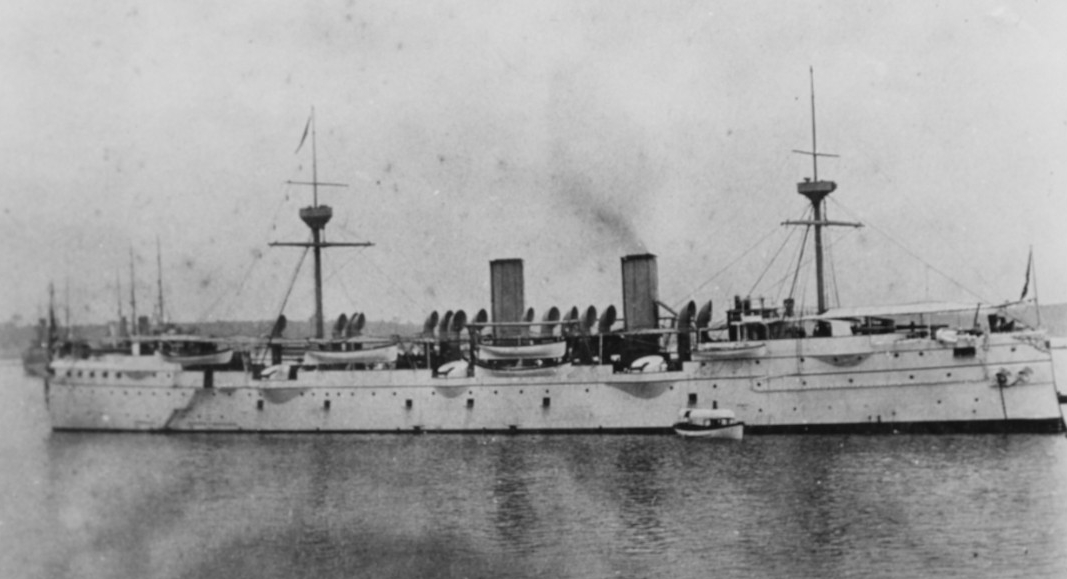

The fourth Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3) was laid down on 5 May 1887 at Philadelphia, Pa., by William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Building Co.; launched on 6 October 1888, sponsored by Mrs. Theodore D. Wilson, wife of Chief Constructor Wilson; and commissioned on 7 January 1890, at the Cramp Yard, Capt. Winfield S. Schley in command.

Baltimore got underway and departed Philadelphia on 13 January 1890. Arriving at the Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., on 15 January, she entered the yard and remained there until 25 April. After clearing the yard, she remained in the lower Chesapeake Bay until 7 May, when she departed Hampton Roads, Va., and steamed to Annapolis, Md. The next day, she visited Baltimore, Md., at the request of its citizens, and remained there until 14 May when she shifted back to Annapolis. She cleared Annapolis on 15 May and steamed directly to Key West, Fla., arriving on 20 May. Baltimore became the flagship of the North Atlantic Squadron on 24 May. Getting underway again on 25 May, she visited Port Royal, S.C. (28 May-5 June) and Charleston, S.C. (5-8 June), before arriving at New York, N.Y., on 12 June. After a four-day visit, she was underway again, on 16 June, bound for a return to the Norfolk Navy Yard. Arriving on 17 June, she remained until 21 June, when she was ordered to return to New York, and reached her destination the next day. Departing again on 27 June, she steamed to Portland, Me. Arriving on 29 June, the cruiser would operate in the waters off Maine into August and making port visits to Portland (29 June-12 July), Bath (12-17 July), and Bar Harbor (18 July-4 August). She returned to New York, on 6 August, and embarked President Benjamin Harrison and his entourage. On 9 August, she got underway bound for a return to New England. She reached Boston, via Nantucket, Mass. (10-11 August), on 11 August. Three days later, the flag of the Commander-in-Chief, North Atlantic Squadron, was transferred to Philadelphia (Cruiser No. 4), and Baltimore was detached for special duty. Departing Boston on 14 August, she arrived at New York the next day, to convey the remains of the late Capt. John Ericsson, designer of the ironclad Monitor, from New York to Stockholm, Sweden. Departing on 23 August, she arrived at Stockholm on 12 September.

Baltimore remained at Stockholm, until 23 September 1890. At this time, she departed to call at a series of ports in Europe. These included Kiel, Germany (25 September-8 October); Copenhagen, Denmark (5-18 October); Lisbon, Portugal (23 October-10 November); Port Mahon, Minorca, Spain (1-18 November); Naples, Italy (20 November-11 December); Spezzia, Italy (12-18 December); and Villefranche, France (19 December-28 January 1891). While at Villefranche, Capt. Schley received orders on 28 January to proceed with the ship to Valparaiso, Chile, for duty on the South Pacific Station.

Baltimore sailed on 28 January 1891, first to Toulon, France (28 January-15 February); then on to the British Crown Colony at Gibraltar (18-20 February); Porto Grande, Cape Verde Islands (25 February-1 March); Montevideo, Uruguay (14-22 March); Sandy Point, in the Straits of Magellan (28-30 March), and Talcahuano, Chile (2-6 April), before arriving at Valparaiso on 21 August. She protected American citizens during the Chilean revolution, landing 36 bluejackets and 18 marines to protect the U.S. Consulate at Valparaiso, on 28 August. She then departed on 4 September, and arrived at Mollendo, Peru, on 9 September, to land Chilean political refugees. She departed that same day and returned to Valparaiso on 14 September.

Just over a month later, on 16 October 1891, a mob attacked a group of sailors on shore leave from the cruiser outside the True Blue Saloon in Valparaíso, after one of the American sailors spit on a picture of Arturo Prat, a Chilean national hero. One sailor was killed, another subsequently died from his wounds, and seventeen other sailors were injured. This heightened tensions between the two nations and prompted President Harrison to send a strongly worded message to Congress. Chile later apologized and paid the U.S. $75,000 in gold. With the dissipation of the crisis, Baltimore departed Valparaiso, on 11 December, and after touching at Callao, Peru (15-19 December), she steamed into the Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, Calif., on 5 January 1892. She entered the yard and underwent maintenance until 6 April.

Baltimore cleared the yard and shifted to San Francisco. Three days later, on 9 April 1892, she got underway again and steamed south down the California coast to San Diego, Calif., reaching on 12 April. Remaining there until 30 April, she got underway again and steamed northward up the coast to the Pacific Northwest. From May to August, she visited cities throughout the states of Oregon and Washington before departing Port Townsend, Wash., on 16 August, and standing in to San Francisco, on the 19th. From there, the cruiser shifted to Mare Island, on 21 August, and underwent maintenance until 25 September. With her yard work completed, she steamed directly to San Diego (27 September-7 October), en route to visits to at Redondo, Calif. (7-10 October), and the Mexican ports of Mazatlan (15-18 October), and Acapulco (21-24 October). From there she continued southward to San Jose, Guatemala (27 October-5 November), Panama, Colombia [Panama] (10-19 November), Callao (26 November-11 December), and back to Valparaiso (16-26 December). Having spent the Christmas holiday at Valparaiso, she was underway again on Boxing Day, steaming south for Cape Horn and a return to the U.S. east coast.

Baltimore arrived at Punta Arenas, Chile, on New Year’s Day 1893, and remained until the 3rd. Continuing on, she sped into the Atlantic and made port visits to Montevideo (9-23 January), Barbados, British West Indies (12-13 February), and St. Thomas, Danish West Indies (15-18 February), before passing between the Virginia capes and dropping anchor at Lynnhaven Roads, Va., on 23 February. The next day, she shifted to Hampton Roads, Va., before departing on 26 February, for New York. Arriving at New York the next day, she remained there until 30 March. During this time she participated in a naval rendezvous and review. Departing on 30 March, she moved to Hampton Roads, where she arrived the next day. Over the course of the next several weeks, she operated from Hampton Roads in the waters off the Virginia coast. On 24 April, she got underway and steamed back to New York. Arriving on 25 April, she remained at New York into September, during which time, Baltimore was re-assigned to the Asiatic Squadron. Clearing New York on 25 September, she steamed eastward across the Atlantic and through the Straits of Gibraltar, into the Mediterranean Sea. En route to Asia, she touched at Algiers, Algeria (1 October); Alexandria, Egypt (17 October -3 November); Port Said, Egypt (3-7 November) before passing through the Suez Canal, in advance of steaming to Colombo, Ceylon [Sri Lanka] (25 November-2 December). Continuing on she visited Singapore (10-14 December), the spent the Christmas and New Year’s holidays at Hong Kong (22 December-2 January 1894). Going to sea again, she steamed across the East China Sea into the Sea of Japan and arrived at Yokohama, Japan, on 10 January. While at Yokohama, she became the squadron flagship on 16 January.

Getting underway again from Yokohama, on 19 February 1894, she steamed to Yokosuka, Japan, (19-27 February), before returning to Yokohama (27 February-26 March). She cleared Yokohama on 7 April, and steamed to China, standing in to Woosung [Wusong] (13 April-12 May). Returning to Japan, she arrived at Nagasaki (14 May-3 June), before moving to Chemulpo [Inchon], Korea, reaching on 5 June. With the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894-17 April 1895), Baltimore cruised the waters between China and Japan, observing the war and protecting American interests. With the war’s end, the cruiser continued to ply East Asian waters into December 1895. On 3 December 1895, the squadron’s flag was transferred, and Baltimore departed Yokohama, for a return to the U.S. Steaming eastward across the Pacific, she paused at Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands (23 December-10 January 1896), en route to the west coast. Baltimore arrived at Mare Island, on 21 January 1896 and entered the yard, where she was placed out of commission for overhaul on 17 February 1896.

Recommissioned on 12 October 1897, Baltimore sailed on 20 October for the Hawaiian Islands and remained there between 7 November 1897 and 25 March 1898. Amid the increasing likelihood of war with Spain, she joined Rear-Adm. George Dewey’s squadron at Hong Kong on 22 April 1898. The force sailed from Mirs Bay, China, on 27 April, setting course for the Spanish-held Philippine Islands (P.I.).

Dewey’s ships approached Manila “at early daylight” on 1 May 1898, Capt. Nehemiah M. Dyer, Baltimore’s commanding officer, later wrote, “close up to the shipping off the city...” The commodore signaled: “Prepare for general action,” while the Spanish shore batteries near the old city of Manila opened fire to engage the Americans at long range. With Olympia (Cruiser No. 6) leading, the U.S. squadron stood toward the anchored ships of Contraalmirante Patricio Montojo y Pasarón that lay arrayed, Dyer observed, “in a somewhat irregular crescent…extending from off Sangley Point to the northeast, and in readiness to receive us, their left supported by the batteries on Sangley Point.”

At 5:40 a.m., following Olympia’s lead, Baltimore opened fire with her port guns at a range of 6,000 yards. The U.S. column then passed down the Spanish line, turning to port when it reached the latter’s left, the Americans opening up with the starboard batteries on the next pass. With distances ranging from 2,600 to 5,000 yards, Dewey’s warships thrice engaged the enemy in that manner until the commodore signaled: “Withdraw from action” at 7:15 a.m. The U.S. men-of-war retired into Manila Bay where, “upon reaching a convenient distance,” Dewey signaled: “Let the people go to breakfast.”

In response to the signal from Olympia at 8:40 a.m., “Commanding officers repair on board the flagship,” Capt. Dyer traveled from Baltimore to Olympia, where he “received an order to intercept a steamer coming up the bay, reported to be flying Spanish colors.” Baltimore immediately set out upon that errand as soon as Capt. Dyer returned to his ship, but soon discovered the stranger to be British, not Spanish. Dyer reported his findings to the commodore, who had, meanwhile, made the signal to his force “to get under way and follow [Dewey’s] motions” when Baltimore was about two miles to Olympia’s south-southwest, en route to investigate the British steamship.

“Designated vessel will lead,” the commodore signaled at 10:55 a.m., adding Baltimore’s distinguishing pennant. Dewey directed his ships to open fire on the shore batteries, then ordered them to close up. Baltimore obediently stood in, steering to a position off the “Cañacoa [sic – Canacao] and Sangley Point batteries” when she opened up with her starboard guns from “about 2,800 yards, closing in to 2,200, between which and 2,700 yards our best work was done,” Dyer recounted later, “slowing the ship dead slow, stopping the engines as range was obtained.” Baltimore fired rapidly and accurately, pounding the Spanish artillery as well as the gunboat San Antonio de Ullua, “practically silencing the batteries in question before the fire of another ship became effective,” Dyer wrote, “owing to the lead we had obtained in our start for the supposed Spanish steamer.”

The Spanish guns fell silent and the white flag of surrender soon appeared above the arsenal at Cavite, upon which the commodore signaled in succession “prepare to anchor” (1:20 p.m.) and “Anchor at discretion” (1:30). At that point, Baltimore’s commanding officer exulted: “The victory was complete.”

Spanish shells had hit Baltimore five times during the action. “The most serious,” wrote Lt. Cmdr. John B. Briggs, the executive officer, “happily attended with no serious injury to any officer or man, came from a 4.7-inch steel projectile, which entered the ship’s side forward of the starboard gangway, about a foot above the line of the main deck… [that] passed through the hammock netting, down through the deck planks and steel deck, bending and cracking [the] deck beam in wardroom stateroom No.5 then glanced upward through the after engine room coaming, over against the cylinder of No. 3 6-inch gun (port), carrying away lug and starting several shield bolts and putting the gun out of commission; deflected over to the starboard side, striking a ventilator ladder and dropping on deck.” As the round had passed through the ship, “it struck a box of 3-pounder ammunition of the fourth division, exploding several charges, and wounded Lieutenant Kellogg, Ensign [Noble E.] Irwin, and 6 men of the gun’s crew – none very seriously.” The second hit caused a slight leak in the exhaust pipe of the starboard blower, the third exploded in a bunker, the fourth broke up in a clothes locker, and the fifth slightly bent the starboard forward ventilator.

Although Baltimore’s gunners had experienced “considerable trouble” with firing devices, with extractors, springs, and firing pins breaking and bending, and wedge blocks jamming, grease and dirt insulating the connections of electric firing attachments, the ship’s fire had been accurate and rapid, with officers and men exhibiting a “steadiness and cool bearing…was that of veterans.” The “shock of discharge” of the 8-inch guns of her second division destroyed the “upper cabin skylight, the after range finder, and the two whaleboats hanging from the davits.” Her sailors used leak stoppers and rubber and iron patches to plug the hull damage on the port side, while Ens. Irwin, “devoting intelligent personal efforts to the accomplishment of the work,” restored No.4 gun for use by the following afternoon [2 May]. “The fact that the ship was so rarely hit,” Capt. Dyer concluded, “gave few opportunities for conspicuous acts of heroism or daring, but the enthusiasm and cool steadiness of the men gave promise that they would have been equal to any emergency.”

Baltimore remained on the Asiatic Station convoying transports and protecting U.S. interests over the ensuing months, departing Manila on 6 September 1898 for Hong Kong, for docking. After undergoing a week of maintenance, she cleared the yard and steamed back to the Philippines, arriving at Manila on 18 September. The cruiser spent the next several months, until 26 December, convoying troop and supply transports. On 28 December, she arrived at Iloilo, P.I., to defend American interests there. The cruiser remained until 8 February 1899, when she departed for a return to Manila, arriving on 10 February. Four days later, she steamed out of Manila Bay, bound for Hong Kong. Reaching on 17 February, she docked and awaited the arrival of the Philippine Commission. Getting underway again on 2 March, she returned to Manila two days later. Just over three weeks hence, on 26 May, she cleared Manila late in the day and steamed into Lingayen Gulf, early the next day. While in these waters, on 31 March, Baltimore provided naval gunfire support to U.S. troops, bombarding Filipino insurgent trenches at Dagapan. She continued cruising these waters until 3 May, when she began her return to Manila, where she arrived on the 4th. The same day as her arrival, Baltimore became the flagship for the Asiatic Squadron.

Baltimore remained at Manila until 12 August 1899, when she got underway and shifted across Manila Bay to Corregidor Island, where she endeavored to dislodge the grounded U.S. Army transport Hooker until 14 August. Afterward, she cruised the waters around the Philippine Islands into January 1900, supporting the occupation of the formerly Spanish-held archipelago. One incident of note occurred on 10 December 1899, when she rendezvoused with an Army expedition at Subic Bay and to occupy the naval station at Olongapo with marines. On 17 January 1900, she arrived at Hong Kong and docked there through 6 March. Returning to the Philippines, on 8 March, she continued to support the efforts of U.S. occupation forces and protect U.S. interests in the islands until 5 April, when she set a course for Japan. She reached Yokohama, on 11 April, and remained there until 1 May. Shifting to Kobe, Japan, on 2 May, she received orders to return to the United States. Initiating her transit via the Suez Canal on 6 May, Baltimore arrived at New York on 8 September. With her return, she was placed out of commission at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on 27 September.

Baltimore was placed back into commission at the New York Navy Yard on 6 May 1903, Cmdr. John B. Briggs in command. From 5 August to 23 December 1903, she served with the Caribbean Squadron, North Atlantic Fleet, taking part in summer maneuvers off the coast of Maine, in the Presidential Review at Oyster Bay, Long Island, N.Y. (15-17 August), and in patrolling the waters off the island of Hispaniola in order to protect U.S. interests there into 1904. On 25 March, the cruiser was at Pensacola, Fla., to rejoin the Atlantic Fleet. Between 28 May and 26 August 1904, she was attached to the European Squadron and cruised in the Mediterranean. On 26 September, she departed Genoa, Italy, bound for a return to the Asiatic Station via the Suez Canal. She arrived at Cavite, P.I., on 11 November. She remained in port there until 1 December, when she set a course for Hong Kong. Reaching on 4 December, she remained three days and then got underway for Chefoo [Yantai], China, where she would spend the Christmas and New Year’s holidays.

Baltimore got underway again on 6 January 1905, and returned to Cavite via Hong Kong (10-23 January). Reaching on 25 January, she remained there until 26 April. Then after making a visit to Malampaya Island, P.I. (27 April-1 May), she stood back in to Cavite on 2 May. Three days later, she departed for China, and made port visits to Shanghai (10-25 May) and Taku (28 May-5 June), before returning to Shanghai (8-12 June) to refuel, before departing to rejoin the fleet in the Philippines. The ship arrived back at Cavite on 18 June. Two weeks later, on 1 July, she was underway again for a return to China. Arriving at Woosung on 6 July, the cruiser remained in Chinese waters into the following year. During this time, she made port visits to Chefoo; Taku; Chemulpo, Korea; and Shanghai. From 29 October-20 November, her commanding officer was the Senior Officer Present for the U.S. force in the Yangtze River. Subsequently, she also visited Chinkiang [Zhenjiang] and Nanking [Nanjing] on the Yangtze. She cleared Woosung on 4 February 1906, and returned to Cavite on 8 February.

Baltimore remained at Cavite until 15 March 1906, then she returned to Hong Kong to dock (21-28 March). Returning to Cavite for coal and stores (30 March-5 April), Baltimore departed to visit the Greater Antipodes. She reached Sydney, Australia, on 19 April and remained there a month. Getting underway again on 19 May, she steamed to Auckland, New Zealand (24 May-23 June), before returning to Australia at Melbourne on 30 June. Departing on 21 July, she continued on to Townsville, Australia (1-2 August), before returning to the Philippines at Zamboanga on 12 August. She continued to patrol the waters of the archipelago into 1907. After receiving orders to again return to the U.S., she cleared Cavite on 9 February 1907, and again transiting via the Suez Canal, stood back in to the New York Navy Yard on 26 April. The cruiser was then again placed out of commission on 15 May.

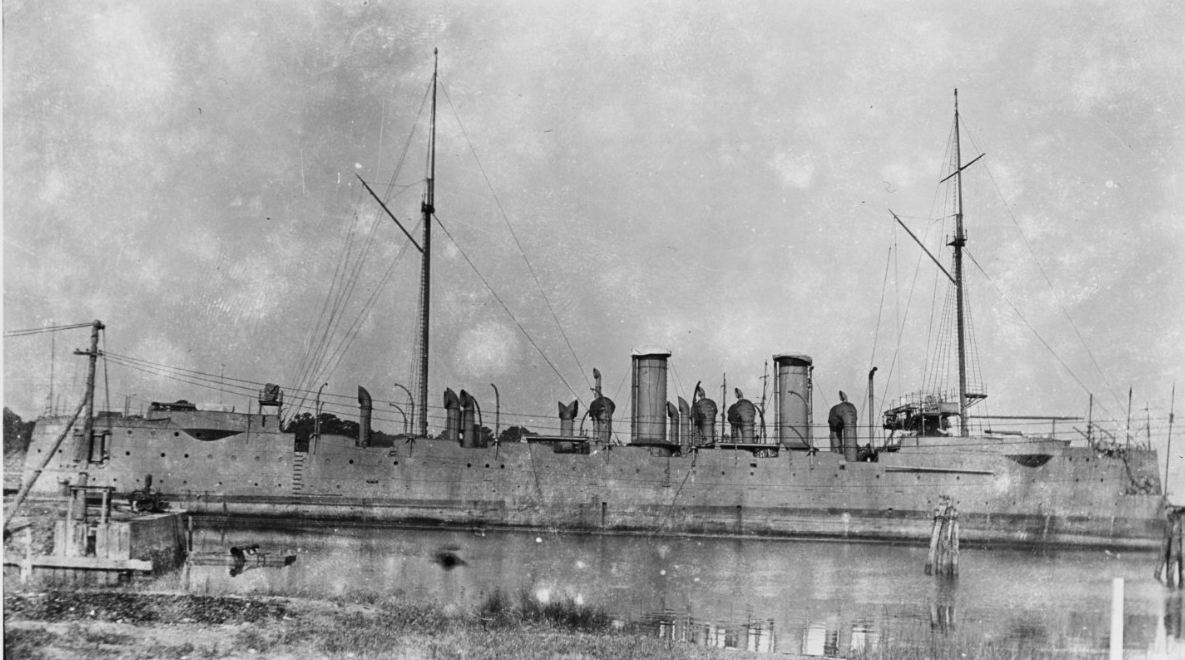

Baltimore was again placed in commission in reserve at the New York Navy Yard, on 20 January 1911, Cmdr. Roger Welles in command. Shifting to Charleston [S.C.] Navy Yard, Baltimore served as a receiving ship there (30 January 1911-20 September 1912). She departed Charleston, on 20 September, arriving two days later at Sewalls Point, Va., after two days coaling and taking on stores, she departed on the 27th, via the Delaware Breakwater, for Tompkinsville [Staten Island], N.Y., in company with the Reserve Torpedo Flotilla. Arriving on 29 September, she awaited orders to proceed to the North River anchorage for the Naval Review. She stood at North River (3-15 October), before entering the Philadelphia Navy Yard (17 October-1 November). Initially departing on 1 November, for the Dominican Republic, she entered the Norfolk Navy Yard for repairs on 3 November. She was then placed in first reserve on 11 November 1912 at the Norfolk Navy Yard; Baltimore remained in the yard until 16 April 1913. Getting underway again, she steamed to the Charleston Navy Yard, to be refitted as a mine planter and was then decommissioned on 6 May 1913.

Recommissioned on 8 March 1915, Cmdr. Frank H. Clark in command, Baltimore cleared Charleston on 1 April, and set course for Hampton Roads, where she arrived on 4 April. The mine planter spent the next several months conducting mining experiments and training in the lower Chesapeake before entering the Norfolk Navy Yard on 21 June for repairs. She cleared the yard on 27 July and steamed northward to Tompkinsville, to receive mine charges. The mine planter then steamed to Narragansett Bay, R.I. Arriving on 30 July, she would spend the next month conducting mining experiments and training exercises in the waters off Rhode Island and Massachusetts, before returning to Hampton Roads, on 28 August. After six weeks conducting training and target practice in the waters around Hampton Roads, she departed on 9 October, and steamed back to Newport, on 11 October, to load a new supply of mines. Departing on 14 October, she was in the North River (15-17 October), before returning to the lower Chesapeake Bay and arriving at Yorktown, Va. to commemorate the surrender of Lord Cornwallis in 1781 (18-19 October). She spent most of the remainder of 1915 conducting additional mining experiments both off Virginia and New York, before entering the Charleston Navy Yard on 22 December. Baltimore remained there until New Year’s Day.

Getting underway again on 1 January 1916, Baltimore arrived at the Norfolk Navy Yard on 3 January, and after shifting to Hampton Roads (5-6 January), she cleared the lower Chesapeake and steamed to the Caribbean to participate in the Atlantic Fleet’s annual winter training. Operating with different divisions of the fleet, Baltimore conducted tactical training, target practice, and mining experiments off Cuba to 25 March. Arriving at Pensacola, on 30 March, she remained until 9 April, when she got underway for northern waters, via Hampton Roads (13-14 April). The ship arrived at Portsmouth (N.H.) Navy Yard (17 April-18 May). Clearing the yard, she spent most of the remainder of the year conducting mining experiments off the New England coast. She returned to Hampton Roads, and remained in the lower Chesapeake, through the end of the year.

In January 1917, she again steamed to the Caribbean to conduct the annual winter fleet training. With the heightened tensions with Germany as a result of the latter’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917, the fleet consolidated at Guacanayabo Bay, Cuba, before moving to the more secure anchorage in the York River off Yorktown.

At the time of the U.S. entry into World War I on 6 April 1917, Baltimore was training people, along with assembling and deploying anti-submarine nets in the lower Chesapeake Bay. On 1 May, she shifted from Yorktown, (Base No. 2), to the Norfolk Navy Yard. On 24 July, Commander, Mine Force, Atlantic Fleet transferred his flag from the mine planter San Francisco to Baltimore. She departed on 5 August, and steamed to New London, Conn. (Base No. 22), where she arrived the next day. She remained in port until 10 September, when she got underway for a visit to Newport, R.I. (Base No. 12), from 10-14 September. Returning to New London on the 14th, she remained until 26 October, when she departed bound initially for Hampton Roads; she continued into the York River and moored off Base No. 2 on 28 October. The next day she shifted to Tangier Island (Base No. 1), and later moved to Hampton Roads on 4 November. Clearing the Virginia capes on 9 November, she proceeded to Newport. Arriving on 10 November, she moved to New London on 14 November, then returned to Newport on the 15th.

Prior to the decision to proceed with the mine barrage in the North Sea between Scotland and neutral Norway, the Navy’s mine force included only two minelayers fit for the project, Baltimore and San Francisco. They actually possessed a very small minelaying capacity, and it became necessary, as one of the first steps in preparation for the project, to greatly enlarge the force by taking over a sufficient number of merchant ships and converting them into minelayers, to obtain and train the officers and crews for these vessels, and to secure the requisite merchant tonnage for transporting the mines and other material to Europe. On the basis of an estimated output of 5,000 mines a week and of one minelaying operation a week, the department concluded that the mine force should have a capacity of at least 5,000 mines ready to lay, which, if all went well, would insure the laying of the northern barrage in three months. San Francisco and Baltimore had a combined capacity of only 350 mines. It was necessary, therefore, to create practically a complete new mine squadron to secure the requisite capacity. Vessels were desired of ample size, yet handy in tactical formation; serviceable condition as to engines, boilers, pumps, etc.; good cargo handling equipment adaptable for handling mines; internal arrangement suitable for installation of mine tracks on two or three decks; speed of 14 to 20 knots; and generally seaworthy. From data on file in the Navy Department, it was found that four vessels of the Morgan Line, running between New York, New Orleans, and Galveston, were generally satisfactory for the purpose. They had been built by the Newport News Shipbuilding Co. to replace vessels of the Prairie class, purchased by the Navy in the Spanish-American War, and were in good condition. They were 391 feet long, 48 feet beam, and 20 feet draft when loaded as minelayers. They were capable of a sustained sea speed of 14.5 knots and had ample bunker capacity. Their capacity was estimated at 800 to 850 mines each. Thus, eight vessels were acquired for conversion into minelayers. With San Francisco and Baltimore they formed a squadron of ten vessels, with a total capacity of about 5,500 mines.

The officers and crews of Baltimore and San Francisco, together with selected officers and men who had had previous experience in the small mine force, provided the nucleus around which the new force was built and trained. At the direction of the Bureau of Ordnance, Baltimore was detailed to carry out certain practical experiments with the Mark VI mine and San Francisco was tasked with training the men for the new mine planters. One of the first measures taken to train the new personnel was the establishment by the Bureau of Navigation of a mine force training camp at Cloyne Field Barracks, Newport, under the Rear Adm. Joseph Strauss, Commander, Mine Force. This camp was established on 11 November and accommodations were provided here for 1,050 men. Baltimore continued to operate from Base No. 12 through November and into December 1917. The mine planter carried out tests and performed such experiments as she could with improvised material. She also assisted in the design of some parts of the gear, notably the means of assembling the antenna floats with the mine and their release gear. She departed on 20 December bound for Tompkinsville (Base No. 21), en route to the New York Navy Yard to fit out for distant service. She arrived on 21 December and on 22 December, Baltimore and San Francisco then entered the New York Navy Yard for their final outfitting for distant service in European waters.

An urgent request had come from the British Admiralty about 1 March 1918, for the services of one or two minelayers to help out in laying a minefield in the North Channel of the Irish Sea, using British mines. This passage was used by slow convoys to the west coast, making port first at Lamlash in the island of Arran, and submarine activity here needed to be checked. The sinking of the British troopship Tuscania on 5 February in this vicinity by UB-77 (Kapitänleutnant Wilhelm Meyer commanding), confirmed this need. At that time, only San Francisco and Baltimore could be considered for this duty, and as the former was flagship, Baltimore was dispatched. To the message asking "How soon can you go?," Capt. Albert W. Marshall answered "Right away," and on 4 March 1918, the ship cleared New York, to join Leviathan (Id. No. 1326) as escort for a fast convoy out of Halifax, Nova Scotia [N.S.] (Base No. 23). Arriving on 7 March, Baltimore and the convoy stood out across the Atlantic, the next day. Baltimore, arrived at Greenock, Scotland, on the Clyde, on 17 March 1918, and was the first U.S. minelayer to arrive in British waters. Ready for work, Baltimore was forced to wait before engaging in her anticipated mission as her first mines were not delivered until 13 April.

Baltimore remained at the Clyde for about three weeks, during which time she was fitted out with paravanes and taut wire measuring gear, and opportunity was taken to send parties of officers and men to Grangemouth, Scotland, for instruction on board the British minelayer HMS Princess Margaret in the British H-2 mine and Mark XII sinker. The mines were fitted with deep switches and calibrated so as to be inoperative when planted nearer the surface than 50 feet. No sinking plugs were used. During this period Capt. Marshall also visited Grangemouth to discuss matters with Rear Adm. Lewis Clinton-Baker, R. N., who had been ordered by the British Admiralty to arrange all details in connection with laying the above-mentioned minefield. Capt. Marshall, and Capt. Lockhart Leith, R. N., then visited Larne, Ireland [Northern Ireland] Buncrana, Ireland [Republic of Ireland] Ardrossan, Scotland; and Lamlash, Isle of Arran, Scotland, and discussed the procedure for carrying out the mining operations with the senior naval officers at those ports. Lamlash was selected as the base from which Baltimore should operate. Mines were supplied by train from the mine depot at Immingham, England. The field was designed to consist of one line of mines at 65 feet where the water was less than 20 fathoms: one line at 65 feet and one line at 95 feet in water between 20 and 30 fathoms; one line at 65 feet, one line at 95 feet, and one at 125 feet in water of 30 fathoms and above. The mines were to be laid in groups of four, spaced 100 feet between mines in each group, and groups to be 300 feet apart.

All operations were carried out at night with Baltimore being screened by two destroyers. The first operation laid 179 mines 65 feet below Low Water Over Sweep [L.W.O.S.] (13-14 April) Before Baltimore's next trip, her own mechanics extended the launching deck tracks, to accommodate 180 instead of 170 mines, since the British naval authorities wished her to plant the larger number each time. She followed the first excursion with a second operation, where she laid 120 mines 95 feet below L.W.O.S and 60 mines 125 feet below L.W.O.S. (18-19 April). The third laid 180 mines 65 feet below L.W O.S. (21-22 April) and another 180 mines 95 feet below L.W.O.S. (27-28 April). She then laid 180 mines 125 feet below L.W.O.S. (1-2 May). The report made by Rear Adm. Clinton-Baker, RN, who was in general command of Baltimore's operations, remarked that “Baltimore laid the lines of mines (as planned) with extreme accuracy; this reflects the greatest credit on Capt. Marshall and his navigating officer...”

Minelaying operations were discontinued on 6 May 1918, by orders from the Admiralty on account of a skimming sweep of the minefield having disclosed several shallow mines at the northern end of the field. This was likely due to the very uneven nature of the bottom of the channel. This skimming sweep was made at a depth of 30 feet, giving from 30 to 33 feet at the cutters. Actean sweeps were used. While the sweeping was in progress, one mine was swept up which had 60 fathoms of mooring cable attached. As all mines planted in this field were set for fixed moorings of approximately 45 fathoms, tests were immediately carried out at Grangemouth to ascertain the reliability of the locking device in the Mark XII sinkers. The results of this test showed the possibility of the locking nut stripping the threads and allowing the full length of the cable on the reel to run out. These sweeping operations, 1-5 May, when a mine was exploded by the sweep in position latitude 55 33' 15" N., longitude 6 42' 45" W. Extensive countermining immediately took place in lines A, B, and C, lasting for a period of between 15 and 30 seconds, and apparently detonating all mines in these three rows. Sweeping operations were resumed in the North Channel on 20 May, when the southwestern portion of D line was skim swept at a depth of 36 feet and found nothing. The following day sweeping continued, but again nothing was found. These sweeping operations continued until 29 May, when the entire North Channel deep mine field had been swept at a depth of approximately 36 feet. A few shallow mines were found in lines D and E, but not nearly so many as were found in the other lines. Soundings obtained by the vessels engaged in making the skimming sweep showed considerable irregularity in the bottom and much variation from the survey soundings which were used for setting the fixed moorings. This was particularly true of the northeastern part of the field.

Prior to the discontinuation of the laying operations by Baltimore, it appeared as though it would be impossible for her to complete this mine field in time to join the mine squadron for the first operation in the North Sea barrage. Accordingly, the Navy Department was requested to send either one or two of the new minelayers which were most nearly completed to assist her in order that all vessels might be available as soon as operations could begin in the North Sea. Roanoke (Id. No. 1695) was the only one that could be considered for such an early departure. She held some minelaying exercises off Cherrystone, Va., in preparation for her deployment, then proceeded to Newport, where she received a draft of 250 men for the mine bases in Scotland. As it turned out, Roanoke was detained a few days in New York, waiting to join a convoy. She finally sailed on 3 May. Before her arrival, however, Baltimore's operations in the North Channel had been discontinued. Although prepared to do so, Roanoke took no part in Baltimore's mining operation. She remained several days at Lamlash, then sailed for Invergordon, Scotland (Base No. 17), where she arrived on 19 May, a week before the rest of the Mine Squadron. Baltimore remained on the west coast for several weeks in order to perform experiments for the British in connection with minelaying and minesweeping, then she proceeded to Inverness, Scotland (Base No. 18), where she arrived on 2 June.

In the meantime, early on 26 May 1918, San Francisco, flagship of Mine Squadron One, accompanied by Canonicus (Id. No. 1696), Canandaigua (Id. No. 1694), Housatonic (Id. No. 1697), and Quinnebaug (Id. No. 1687), arrived at Bases No. 17 and 18. Capt. Reginald R. Belknap, Commander Mine Squadron 1, reported that all vessels would be ready to commence minelaying as soon as they had been watered and refueled. The delivery of mine parts, however, had not been up to expectations and prevented the beginning of operations. All of the necessary mine parts were on hand except the antenna floats for mines planted at the lower levels, and it was necessary to wait until a mine carrier had arrived before sufficient numbers of these floats were on hand to enable the necessary numbers of mines to be assembled for the first excursion. Loading, half at Inverness (Base No. 18), and half at Invergordon (Base No. 17), 30 miles away, was necessary for the storage and assembly of mines, all of which came from the U.S. These bases had scant means at first for assisting the ships. The intention for all U.S. naval forces abroad was to be self-supporting and, as such, they were required to draw on the British stocks for very little. After a month, the repair ship Black Hawk (Id. No. 2140) arrived. Serving as flagship for Rear Adm. Joseph Strauss, Commander, Mine Force, Black Hawk took no part in minelaying and remained moored off Inverness. Her equipment of machine tools and repair material, however, made the Mine Force normally independent in regard to upkeep. Except for docking, the British provided little in the way of repairs. A mine embarking schedule was made out accordingly, to include San Francisco, Baltimore, Roanoke, Canandaigua, Canonicus, and Housatonic, for a start on 7 June.

The first excursion was to be a joint operation with the British minelaying squadron. Finally, at 12:45 a.m., on 7 June 1918, the flagship, in company with Baltimore, Roanoke, Housatonic, Canonicus, and Canandaigua, steamed out of the harbor and began the first mining excursion, the next day. The squadron left the bases, rendezvoused outside Cromarty Firth with the British destroyers sent to escort them, then proceed via the swept channels and across the North Sea until they sighted Udshire Light on the coast of Norway. This was used as the point of departure, being the nearest point of land to the position in which the mine laying was to commence. Under escort by British destroyers, at 5:00 a.m., San Francisco and the others commenced mining at 5:38 a.m. By 9:34 a.m., they had laid 153 mines, and “Mine Excursion No. 1” was completed. The ships then turned homeward for Inverness. While en route, there was a submarine alarm, and HMS G.50, flagship of the escorting destroyers, dropped a depth charge. They all returned to Inverness without further incident at 5:15 a.m., on the 9th. After the completion of the first excursion, further minelaying by the U.S. mine force was temporarily prevented by the delayed delivery of mining material. In the meantime, the British minelaying squadron had completed its second and third operations on18 June and 30 June.

Getting underway for the third excursion on 14 July 1918, the U.S. squadron laid 5,395 mines the following day in 4 hours and 22 minutes, the largest number so far laid in a single operation. At 4.20 a.m. on 16 July, while just north of Cromarty Firth, one of the escorting destroyers sheered close in to San Francisco and reported that they were too close inshore. The squadron turned out, stopped and backed, but before headway had been checked Roanoke and Canonicus had grounded. Canonicus was able to back off, but attempts to clear Roanoke proved unavailing until she was lightened as much as possible. She came off easily on the following high tide. In light of the fact that neither vessel sustained any damage, the Commander, Mine Force, recommended no further proceedings and the matter was disposed of by Vice Adm. William S. Sims, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces in European Waters in a letter.

The fifth British operation was carried out on 21 July 1918, in Area C. Several days delay was encountered before the fourth U.S. operation on account of again having to wait for mining materiel. The squadron was reported ready to sail on 25 July, but it was necessary to wait four days more for the escorting and supporting forces from the Grand Fleet. The British and U.S. operations had recently been overlapping each other in such a manner that one squadron was out at sea while the other was loading in port. This required keeping a large part of the Grand Fleet at sea almost constantly, the Commander-in-Chief, therefore, desired that the U.S. squadron should wait until the British squadron had again loaded, so that it would only be necessary to send one force to support both squadrons.

The U.S. squadron sailed on 29 July 1918, laying 5,399 mines the following day. The premature explosions, much more numerous than on any of the previous excursions -- approximately 14% of the mines going off – proved most disconcerting. Instead of the explosions decreasing as experience was gained in the assembly and laying of the mines, the percentage had been gradually increasing and then had suddenly jumped to 14% on this excursion. Losses of 3-4% could be tolerated, but this latter figure was prohibitive, and the causes of the explosions had to be determined and eliminated. Due to the large number of premature explosions which occurred in the fourth operation, the Force Commander ordered the suspension of further minelaying operations until the cause of the explosions had been ascertained and corrected. The next excursion, a joint effort by the British and U.S. squadrons began on 8 August. The efforts to cure the premature explosions on this excursion were found even less successful than before; approximately 19% of the mines had exploded. After laying 1,596 mines, the operation was discontinued and the squadron returned to the bases. It was found that the rubber insulation between the copper plates on the firing device caused a slight current in the firing circuit in the direction necessary to operate it. Although the current was in most cases small, there was a possibility that if it were eliminated the mines would then have sufficient stability so as not to explode after they had been planted. In order to carry out the practical part of the experiments after the theoretical tests had been completed at the bases, San Francisco proceeded to the mine field on 12 August. The improvement obtained in this test was sufficient to enable minelaying to be resumed. The squadron sailed on the sixth excursion on 18 August, and the minelaying was completed on the 19th. The squadron got underway for the seventh excursion on 26 August, and stood out toward the minefield. Saranac (Id. No. 1702) broke down shortly after leaving the base and had to return to Inverness with her full cargo of mines. San Francisco and the remaining eight ships, however, continued and carried out the operation. Unfortunately, dense fog was encountered practically throughout the operation; so thick at times that it was impossible for the vessels to see the next ship abeam, distant only 500 yards.

The eighth excursion was intended as a surprise. Neutral nations had not been notified that Area B was dangerous to shipping, and with this knowledge, enemy U-boats were constantly passing through it on their way to the Atlantic. It was accordingly decided not to notify neutrals about the area, but to secretly route all shipping so as to avoid it, with the hope that U-boats might still attempt to use it after it had been mined. In order to prevent the enemy observing the mining while it was in progress, an elaborate patrol was arranged, beginning the day before the operation and continuing until after its completion. British and U.S. mining squadrons rendezvoused off the Orkney Islands on 7 September and proceeded to carry out the operation. The U.S. laid six lines of surface mines across Area B, while the British laid one line of surface mines parallel. This was really the first joint operation carried out by the British and U.S. squadrons. On several previous occasions both squadrons had been at sea at the same time, but had not been working side by side, so as to necessitate appointing one officer to command the expedition. On this occasion, Rear Adm. Strauss, embarked in San Francisco, was designated to take general charge of both squadrons while mining was in progress.

In the early morning of 20 September 1918, while the U.S. mining squadron was on its way to the minefield to carry out the ninth excursion, a submarine was sighted off Stronsay Firth. She was immediately attacked with depth charges by the escorting destroyers, and at the same time a smoke screen was put out by both the escort and the minelayers. Shortly afterwards, she was again sighted just ahead of San Francisco, and was again attacked. The squadron proceeded through Westray Firth and then to a position about 6 miles to the northward of the western end of the minefield which was laid on 7 September. In this excursion, 5,520 mines were laid in 3 hours and 50 minutes the record number laid by a minelaying force in a single operation. At the same time, the British squadron laid 1,300 mines in a single line parallel and to the northward of those laid by us. Rear Adm. Strauss, on board San Francisco, was in command of the American minelayers while Rear Adm. Lewis Clinton-Baker, CB, RN, commanded the combined forces. The firing devices had been adjusted and there was a reduction of premature explosions on this excursion, being between 5-6%, a marked improvement.

Rear Adm. Strauss attended a conference at Malta which recommended that extensive mine barrages be deployed in the Mediterranean, in locations where the depths of water were much greater than any yet mined. As a first step, Capt. Orin G. Murfin was dispatched from Inverness to Bizerte, Tunisia, to establish a base there, like those in Scotland. Considerable experimenting at home was likewise involved, in order to develop a suitable extra-deep mine and its moorings. A satisfactory design had been developed by the Bureau of Ordnance, but it was essential to conduct a series of practical tests before beginning the manufacture. No vessel was available in the U.S. for this purpose, so Baltimore was ordered home to carry out the required experiments. She proceeded in company with the squadron on its way to the minefield for the tenth excursion as far as Pentland Firth. There she detached and proceeded to Scapa Flow, Orkney Islands, to obtain routing instructions across the Atlantic from the Commander-in-Chief, Grand Fleet. Capt. Belknap remarked upon her departure that “Baltimore's value in the squadron had far exceeded her proportionate capacity.”

Baltimore steamed from Scapa Flow on 28 September 1918, for the United States. She arrived at Halifax, on 10 October, and refueled. Resuming her passage the next day, she entered the New York Navy Yard, on 14 October. While undergoing maintenance in the yard, the Armistice of 11 November ended hostilities.

Despite the war’s end, Baltimore was ordered to continue with her mining experiments. She cleared the New York Navy Yard on 2 December 1918, and stood in to Hampton Roads, the next day. Three days later on 6 December, she departed for the West Indies to conduct experiments in the waters of the U.S. Virgin Islands (U.S.V.I.). She visited St. Croix, U.S.V.I. (12 December) and St. Thomas, U.S.V.I. (21-26 December), before moving on to Culebra Island, off Puerto Rico (P.R.). She arrived on 3 January 1919, and then moved on to San Juan, P.R. (4-6 January). She then proceeded to Charleston Navy Yard (11 January), before returning to Newport on 14 January. With San Francisco needing repairs, the squadron flag was transferred temporarily to Baltimore on 17 January, at Newport. The ship operated from Newport until 7 April, when she departed for New York (8-13 April), en route to Norfolk (14-17 April). She then returned to New York on 18 April, then departed from Tompkinsville a week later, on 25 April, bound for Portsmouth Navy Yard, reaching the next day. Remaining only briefly, she cleared the yard the following day and steamed to Halifax (28 April-15 May), before she resumed operations underway, and stood back in to Tompkinsville on 17 May. She departed on 20 May bound for a return to the lower Chesapeake Bay. Arriving at Tangier Sound on 22 May, she shifted to Hampton roads on 28 May, before returning to Newport on 2 June. Having transferred the flag back to San Francisco, she got underway on 1 July, bound for Portsmouth Navy Yard, arriving on 2 July; she remained there until 9 August. Getting underway again, she steamed to Hampton Roads, reaching on 11 August. While in Virginia, she received orders transferring her to the Pacific Fleet. As such, she cleared Cape Henry and Cape Charles on 27 August and steamed to the Canal Zone (C.Z.).

Baltimore arrived at Cristóbal, C.Z., on 4 September 1919, and remained there until 10 September, when she transited the Panama Canal and crossed to the Pacific. Continuing on, she proceeded to port visits at Puntarenas, Costa Rica (17-26 September) and Amapala, Honduras (28 September) and Acajutla, El Salvador (22 October), before returning to Balboa, C.Z. on 5 November. Returning to sea, she steamed back to Amapala (8 September), en route to San Diego, where she arrived on 20 November. She then steamed northward to San Francisco Bay, where she entered the Mare Island Navy Yard on 23 November.

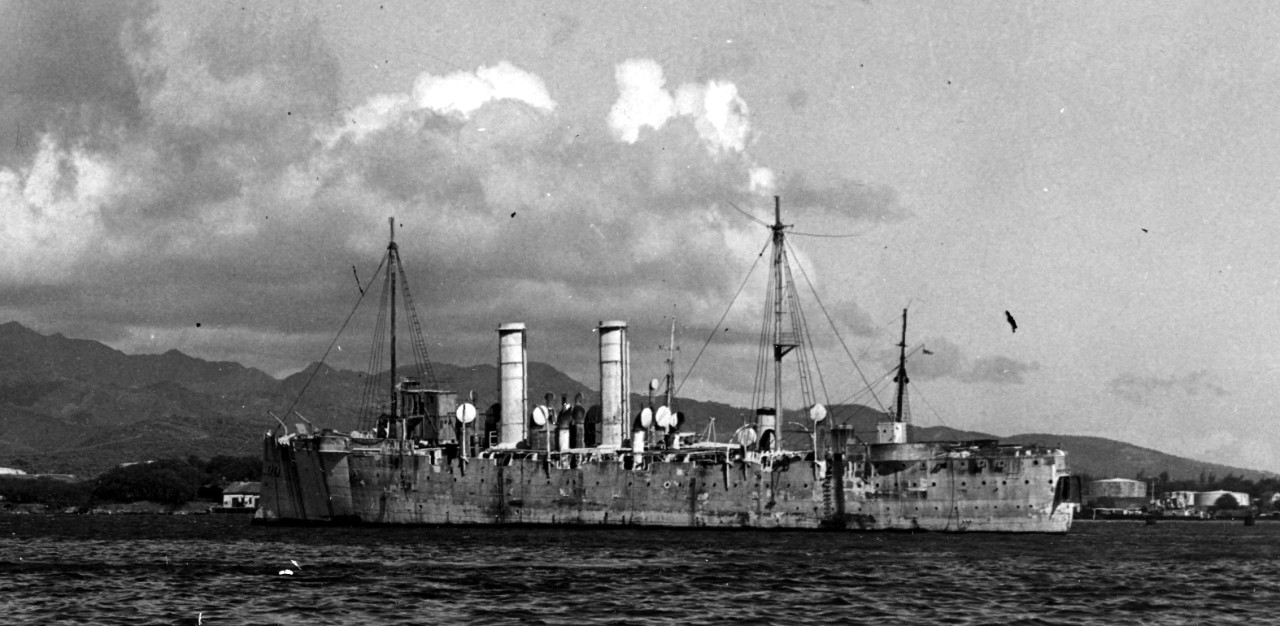

Baltimore, while in the yard, was re-designated CM-1 as part of a Navy-wide administrative re-organization on 17 July 1920. She finally got underway again on 13 August 1920 and spent the following months operating along the California coast.

After the New Year, Baltimore returned to Mare Island on 6 January 1921. After four days in the yard, she stood out and passed through the Golden Gate into the Pacific. Steaming westward, she arrived at Pearl Harbor on 20 January. She spent the remainder of her active career operating from this Pacific base, and she was placed out of commission on 15 September 1922. Stricken from the Navy list on 14 October 1937, the ship was sold for scrap on 16 February 1942.

| Commanding Officers | Dates of Command |

| Capt. Winfield S. Schley | 7 January 1890 – 24 February 1892 |

| Capt. William Whitehead | 24 February 1892 – 12 July 1894 |

| Capt. Benjamin F. Day | 12 July 1894 – 17 February 1896 |

| Capt. Nehemiah M. Dyer | 12 October 1897 – 25 March 1899 |

| Lt. Cmdr. John B. Briggs | 25 March 1899 – 19 May 1899 |

| Capt. J. M. Forsyth | 19 May 1899 – 7 February 1900 |

| Capt. Charles M. Thomas | 7 February 1900 – 16 April 1900 |

| Capt. J. M. Forsyth | 16 April 1900 – 27 September 1900 |

| Cmdr. John B. Briggs | 6 May 1903 – 25 October 1904 |

| Capt. Nathan Sargent | 25 October 1904 – 15 August 1906 |

| Cmdr. James M. Helm | 15 August 1906 – 5 February 1907 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Clarence M. Stone | 5 February 1907 – 15 May 1907 |

| Cmdr. Roger Welles | 20 January 1911 – 1 February 1911 |

| Cmdr. Albert L. Key | 1 February 1911 – 14 June 1911 |

| Lt. William H. Allen | 14 June 1911 – 6 October 1911 |

| Lt. Butler Y. Rhodes | 6 October 1911 – 26 October 1911 |

| Cmdr. Armistead Rust | 26 October 1911 – 2 July 1912 |

| Lt. Butler Y. Rhodes | 2 July 1912 – 31 July 1912 |

| Cmdr. Noble E. Irwin | 31 July 1912 – 17 October 1912 |

| Lt. Butler Y. Rhodes | 17 October 1912 – 30 October 1912 |

| Cmdr. William W. Phelps | 30 October 1912 – 9 January 1913 |

| Lt. Butler Y. Rhodes | 9 January 1913 – 16 May 1913 |

| Cmdr. Montgomery N. Taylor | 8 March 1915 – 1 November 1915 |

| Cmdr. Frank H. Clark | 1 November 1915 – 30 August 1916 |

| Cmdr. Albert W. Marshall | 30 August 1916 – 5 February 1919 |

| Capt. Wat T. Cluverius | 5 February 1919 – 12 June 1919 |

| Capt. Alfred G. Howe | 12 June 1919 – 10 January 1920 |

| Lt. Cmdr. Douglas W. Fuller | 10 January 1920 – 8 September 1920 |

| Capt. Edward McCauley Jr. | 8 September 1920 – 16 May 1921 |

| Capt. Claude C. Bloch | 16 May 1921 – 23 November 1921 |

| Capt. Walton R. Sexton | 23 November 1921 – 18 July 1922 |

| Capt. William T. Tarrant | 18 July 1922 – 15 September 1922 |

Christopher B. Havern Sr.

2 February 2018