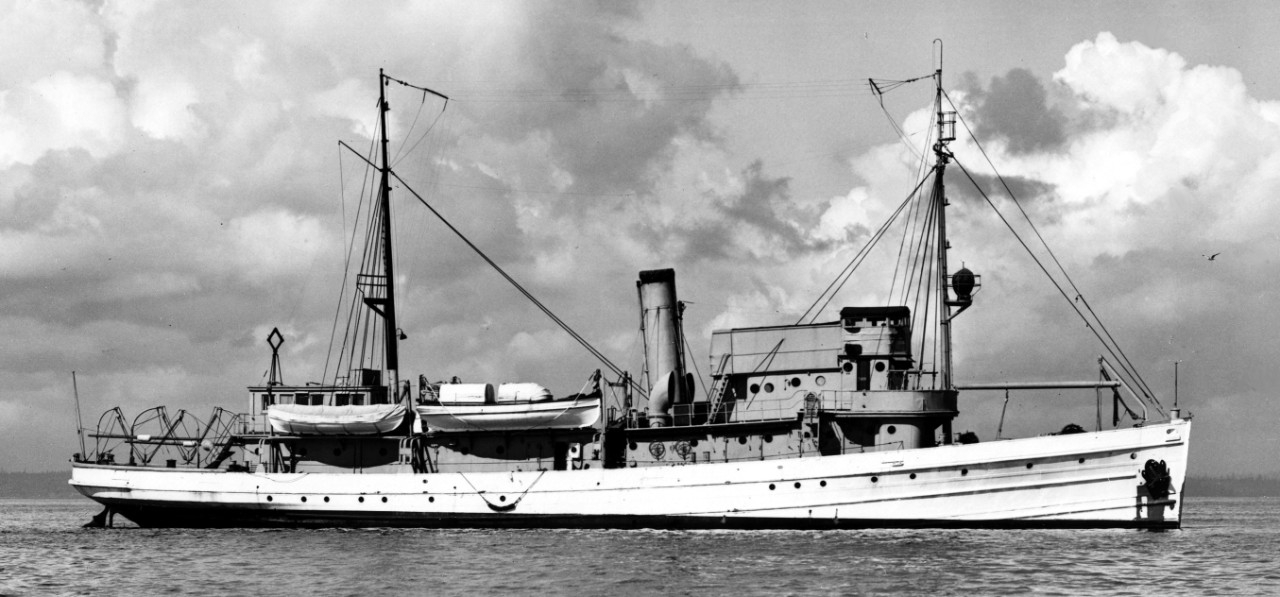

Auk I (Minesweeper No. 38)

1919–1921

A diving bird native to the colder climates of the northern hemisphere.

I

(Minesweeper No. 38: displacement 950; 1ength 187'10"; beam 35'6"; draft 9'9½" (mean); speed 14 knots; complement 82; armament 2 .30-caliber Lewis machine guns; class Lapwing)

The first Auk (Minesweeper No. 38) was laid down on 20 June 1918 at New York City by the Todd Shipyard Corp.; launched on 28 September 1918; sponsored by Miss Nan McArthur Beattie, daughter of a Todd Shipyard foreman; and commissioned at the New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., on 31 January 1919, Lt. Gregory Cullen in command.

Upon completion of her initial fitting out and dock trials, Auk proceeded to Tompkinsville, Staten Island, on the afternoon of 24 February 1919. There, her commanding officer reported to the Commander, Minesweeping Division, Third Naval District. On 2 March, Auk sailed for Newport, R.I., in company with Curlew (Minesweeper No. 8) and arrived there the next morning. At that port, Lt. Cullen attended a conference on board the Mine Force flagship, Baltimore, on the 5th. Returning to the Mine Sweeping Base at New York on the morning of the 6th, Auk left New York waters the following afternoon, bound for Boston.

The minesweeper, rolling and pitching heavily as the winds and seas rose, was proceeding on her coastwise voyage when, in the predawn darkness of the mid watch on 8 March, men in the crew’s compartment detected water entering their space at an alarming rate. While some of the crew bailed doggedly, others rigged a “handy billy” and, later, a wrecking pump, in an effort to cope with the flooding. Lt. Cullen, seeing that Auk was taking water faster than it was humanly possible to pump it out or bail it, prudently decided to seek refuge for his ship.

Auk accordingly altered course at 9:05 a.m. and plunged through the rough seas and a veritable curtain of fog, while her foghorn blared its warning. She anchored that afternoon, but waves breaking over the after deck foiled attempts to rig the heavy-duty wrecking pumps into the after hold (into which the water was coming, through the rudder stock) since it was impossible to remove the hatch without allowing more water to get below in the process. Then, just as the fog began to lift to the northward and the ship prepared to weigh anchor and get underway, the anchor engine jammed. Quick repairs enabled Auk’s men to begin the process of hoisting up the hook, but the slow rate at which it was coming up caused some second thoughts about the whole business--water was gaining in the crew’s quarters. Finally, forced to slip 75 fathoms of chain and her starboard anchor, the minesweeper got underway and eventually reached a safe haven in the lee of Montauk Point.

By the next day, the weather had moderated sufficiently to allow Auk’s crew to pump out the flooded after compartments. While she was attempting to retrieve her lost anchor, the minesweeper received orders to discontinue the search and to proceed to her original destination. Underway as ordered, she reached the Boston Navy Yard at 11:15 a.m. on the 11th and moored alongside sister ship Oriole (Minesweeper No. 7).

Auk remained there for over a month, undergoing repairs and fitting out for her pending duty sweeping the North Sea Mine Barrage. During this time, paravanes (Burney Gear) were installed in the ship; and she underwent necessary upkeep. She departed the yard late on the afternoon of 14 April, standing out of President Roads to anchor for the night off Provincetown.

On the morning of 15 April 1919, after calibrating her compasses, Auk got underway for the Orkney Islands, joining three of her sister ships: Heron (Minesweeper No. 10), Sanderling (Minesweeper No. 37), and Oriole. During their two-week passage, the ships occasionally gained an extra knot or two by hoisting trysails to catch prevailing zephyrs. All went well until two days from their destination, when steering gear casualties briefly disabled first Heron, and then Auk, each time necessitating Oriole’s towing them during their respective times of trouble. Ultimately, the four minesweepers reached Kirkwall, Orkney Islands, on 29 April 1919, shortly after Black Hawk (Id.No. 2140), the Minesweeping Detachment flagship, arrived to establish the headquarters there for the ensuing operations.

Among the last of the minesweepers to reach Orkney Islands, Auk missed the first, experimental, mine clearance (29 April—2 May 1919) that proved but a preliminary to the monumental task that lay ahead. However, tragically, before she actually started operations in the minefields, Auk suffered the first fatality of the operation when, at 9:55 a.m. on 3 May, BM1c William McHaskell, while engaged in unreeling sweep wire from the drum of the anchor engine, was caught between the wrist pin bearing of the engine and the sweeping drum itself and sustained crushing pelvic injuries. Although taken to Black Hawk within minutes, McHaskell died soon thereafter. That evening, a board of inquiry that met to ascertain the particulars of the sailor’s death recommended that safety guards be installed on that equipment in all minesweepers to prevent similar accidents.

Over the next five months, Auk and her sister ships, together with a group of wooden-hulled 110-foot submarine chasers (SCs), supported by a truly Allied flotilla of British and American logistics and repair ships and loaned British Admiralty trawlers, carried out the dangerous task of sweeping some 55,000 mines sown in 1918 between the coasts of Scotland and Norway to bottle up the German U-boats in their North Sea lairs. Auk spent over 95 days on the minefields in the often “dirty” weather associated with the North Sea and, like her sister ships, encountered many frustrations that dogged the sweepers and their supporting craft as they carried out their unprecedented mission of clearing the sea lanes to permit a resumption of civilian commerce in the wake of the Great War [World War I].

Underway from Kirkwall at 6:00 a.m. on 10 May 1919, Auk took S.C. 46 in tow soon thereafter and proceeded to the minefields in company with her division mates, Oriole, Heron, and Sanderling, each in turn towing a chaser. Misfortune, however, seemed determined to stalk Auk. While she was passing sweep wire to Oriole, the line snagged in Auk’s propeller. Slipping the troublesome wire failed to solve the problem, so Oriole took her sister ship in tow; but soon turned over the towing task to Robin (Minesweeper No. 3), which took her disabled sister ship to Lerwick, in the Shetland Islands. There, British divers from the tender Edna removed the sweep on 13 May.

Auk returned to the minefields soon thereafter and teamed with Oriole to conduct a sweep on the afternoon of the 14th. During her first pass, she cut loose three mines, one fouling the “kite” astern and the other two fouling the line itself. Over the next few days, Auk carried out the repetitious task of sweeping, again in company with Oriole. A mine exploding nearby Auk on the afternoon of the 15th shook the ship considerably but apparently did no damage.

The minesweeper varied her daily routine in the minefields, which lasted into late May 1919, by escorting S.C. 356 to Lerwick and back on 17 and 18 May. During the latter half of the month, Auk teamed with, on different occasions, Oriole, Swan (Minesweeper No. 34), or Kingfisher (Minesweeper No. 25). Returning to Kirkwall on 29 May, Auk refueled there from the British tanker Aspenleaf.

During June 1919, Auk participated in the third clearance operation on the barrage, getting underway from Kirkwall for the minefields on 5 June and returning to port on the 27th. She broke up the routine with brief visits to Kirkwall and Otterswick (9 and 12 June, respectively), but spent most of the month on the barrage. This time around, her sweeping partners included the familiar Oriole, Robin, and Swallow (Minesweeper No. 4). Highlighting this operation was the shaking-up suffered by the ship when a mine exploded on 21 June. At 6:27 p.m., an explosion 50 yards astern sent out shock waves that tripped the generators (plunging the engine and fire rooms into darkness) and knocked down part of the brick walls in her two boilers. Fortunately, the damage proved not serious enough to incapacitate the ship and she resumed sweeping operations the next day.

During the next two minesweeping operations that followed, Auk served as the flagship Capt. Roscoe C. Bulmer, for the detachment commander, a highly regarded man, revered by the men he commanded. Capt. Bulmer embarked for the first time at Kirkwall on 7 July 1919 when he broke his broad pennant in Auk shortly before she proceeded to sea. That day, she teamed with her old consort Oriole in sweeping a portion of the field that had been lain on 13 October of the previous year and, on the following day, swept in company with Eider (Minesweeper No. 17).

The 9th of July 1919, however, proved a momentous day. As a chronicler of the North Sea Mine Barrage clearance wrote: “. . . misfortune did not rain; it poured.” Exploding mines damaged three minesweepers, Patuxent (Tug No. 11), and a submarine chaser. Again sweeping in company with Eider, Auk shuddered under the impact of an explosion at 9:25 a.m. that, in turn, countermined another mine 25 yards off her starboard bow; in a chain reaction, a third explosion (probably caused by the second) roiled the sea 30 yards astern, carrying away the sweep and resulting in the loss of a kite and 70 fathoms of precious wire as well. All of those mishaps, however, proved but a preliminary to what transpired soon thereafter.

At 10:00 a.m., an upper level mine exploded beneath Pelican (Minesweeper No. 27), which in turn triggered five simultaneous countermines around her. The little ship disappeared in a veritable cloud of spray that, when it subsided, revealed Pelican, heavily hit, battered, and holed, assuming a list before beginning to settle. As the seemingly mortally wounded minesweeper wallowed in the swells, Auk, with Capt. Bulmer directing the rescue operations, immediately altered course to close her stricken sister ship.

Passing a line at 10:08 a.m., within 10 minutes of the explosions, she drew alongside Pelican. After seeing one hose line part, Auk passed another to aid her stricken sister ship in pumping out the rapidly rising water below decks. The rough seas, however, repeatedly slammed the ships together, damaging lines and hoses, and forcing their replacement. At 10:54 a.m., Teal (Minesweeper No. 23) passed a tow line and began moving ahead with the crippled Pelican, in turn tethered to Auk, astern.

Eider fell in with the group as it labored ahead, securing to Pelican’s starboard side, Eider and Auk acting much in the fashion of water wings, keeping their sister ship afloat between them. Difficulties soon arose, however, as the ships struggled toward the Orkneys. A head sea sprang up, tossing the minecraft about and straining moorings and hose lines. Pump lines carried away and, soon thereafter, shorn of the means for keeping her afloat, Pelican began to settle further by the bow. The pressure of the water in the flooded forward compartments in the damaged ship now buckled and distorted the forward fireroom bulkhead, the only barrier between Pelican and the sea that seemed determined to claim her.

At 11:00 p.m., Capt. Bulmer ordered most of Pelican’s crew transferred to Eider. A dozen volunteers chosen from the crew (all had stepped forward when asked to hazard staying on board), all that was absolutely necessary “to care for the ship,” remained on board Pelican. Gradually, however, the pumps of Auk and Eider, working full capacity after the lines had been repaired and again placed in operation, succeeded in lowering Pelican’s waterline. The battle to keep Pelican afloat continued on into the night and into the predawn darkness, men standing by with axes to chop through the mooring lines should Pelican give any indication of imminent sinking. Finally, on the morning of 10 July 1919, the valiant little flotilla limped into Tresness Bay where Auk’s pumps continued to help lower her sister ship's waterline even further.

Underway to return to Kirkwall at 5:26 a.m., Auk reached her destination a little over four hours later, disembarking the indomitable Capt. Bulmer (whose seamanship many credited with having saved Pelican) soon thereafter. The next day, Auk transported Rear Adm. Elliott Strauss, Commander Mine Force, from Kirkwall to Inverness, Scotland, before she returned thence to Kirkwall, ready to resume operations on the minefields.

Shortly after midnight on 22 July 1919, Capt. Bulmer transferred his command pennant from Black Hawk to Auk and wore it in the ship as she teamed with Oriole during the detachment’s fifth mine clearance operation. Capt. Bulmer disembarked for the last time at 12:17 a.m. on 1 August and, tragically, just three days later suffered severe injuries in an automobile accident. He died on 5 August, and his loss was felt tremendously throughout the detachment, since his intrepid personality had stamped itself on the force and inspired it during his time in command.

Auk subsequently took part in two additional minesweeping operations that lasted through late September 1919, drawing her participation in this epic venture to a close when she anchored at Kirkwall on 26 September 1919. During the first of these missions (mid-to-late August), Auk ranged as far as the coast of Norway, touching at the ports of Scavenger and Hangeand, and Bommel Fjord. During this operation, Auk suffered her second fatality. At 7:15 a.m. on 31 August 1919, a kite wire, jumping out of a chock, knocked BM1c Lee A. Singleton over the side. Auk immediately commenced maneuvering to pick up her lost sailor, simultaneously cutting the sweep wire, throwing over a life buoy, and hoisting the man overboard signal. Sadly, a one-hour search of the vicinity failed to turn up the missing man.

Drydocked at Invergordon on 2 and 3 September 1919 to repair damage suffered when mines exploded close aboard on 30 August, Auk performed local tug and towing duties at Kirkwall in mid-September before resuming operations in the minefields later that month.

Ultimately, her work completed in the often inhospitable climes of the North Sea, Auk and her sister ships, as well as the support craft that had serviced them in one of the Navy’s most formidable peacetime tasks, headed for home. Underway from Kirkwall on 1 October 1919, Auk reached Plymouth, England, on the 5th, and underwent voyage repairs there until the 16th, when she left the British Isles and headed for the coast of France, reaching Brest on the morning of the 17th. After steaming thence to Lisbon, Portugal, for a brief period of upkeep alongside Black Hawk, Auk began the homeward voyage on the afternoon of 24 October. On 9 November, however, the watch discovered that sea water had leaked into the after peak tank and contaminated the oil. Reducing speed to conserve fuel, Auk was taken in tow by Swallow later that day, the former hoisting sail to help maintain her course.

On the morning of the 10th, Auk went alongside Black Hawk in an attempt at underway replenishment, only to have the fuel hose carry away and foul the minesweeper’s propeller. Black Hawk then towed Auk throughout the night. In another attempt at refueling between 9:25 and 11:15 a.m. the next morning [11 November 1919], Auk took on board 20 tons of oil and reached Grassy Bay, Bermuda, six hours later.

Auk reached Tompkinsville, Staten Island, on 19 November 1919. Anchoring in the North River on 21 November, near her old sweeping partner Oriole, Auk lay in that waterway when Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels reviewed the assembled mine force—minesweepers, submarine chasers, and tenders—on the 24th, from the deck of Meredith (Destroyer No. 165). As Daniels subsequently reported: “Upon their return to the United States . . . they [the ships of the Minesweeping Detachment] were given a welcome as genuine as when our dreadnaughts returned from service abroad.” Later, at a luncheon tendered to the officers and men of the Detachment, Daniels “voiced the country’s appreciation of the magnificent and successful completion of that most hazardous and strenuous operation.”

After the tumult of their welcome had died down, the Minesweeping Detachment was demobilized, and its ships scattered throughout the fleet. Auk departed Tompkinsville on the morning of 27 November 1919 and, in company with Quail (Minesweeper No. 15), proceeded up the eastern seaboard, reaching Portsmouth, N.H., on the afternoon of the 28th. During a year in which she remained inactive at Portsmouth, Auk was given the alphanumeric identification number AM-38 on 17 July 1920. She was placed “in ordinary,” with no crew on board, on 28 December 1920 three days after Christmas. Although still inactive, Auk was assigned to Division 1, Minesweeping Squadron, on 8 January 1921.

While Auk lay in reserve, the Coast and Geodetic Survey found itself in urgent need of ships to replace those which, for reasons of age or unsuitability for the work to be performed, had been disposed of. Under the terms of the Executive Order of 12 October 1921, Auk and Osprey (AM-29), renamed Discoverer and Pioneer, respectively, were taken to the Boston Navy Yard, Boston, Mass., and transferred to the Coast and Geodetic Survey on 7 April 1922. The following day, Lt. Cmdr. H. A. Seran, USCGS, took charge of the two former minesweepers.

Discoverer, Lt. Cmdr. Seran in command, stood out on 28 April 1922 and transited the Cape Cod Canal that day. She reached the William Cramp & Sons’ shipyard, at Philadelphia, the following morning and soon commenced a major overhaul and conversion. While ships like Auk were, in general, well-adapted to the kind of work they would be performing in the Coast Survey, being “robust” steel-hulled ships that had proved their ability to keep the sea, their accommodations were too small to take care of the large surveying parties that were to be embarked on board for the hydrographic and topographic work to be undertaken.

Discoverer’s metamorphosis was completed by early August of 1922; and, on the 9th, the ship got underway for the Virginia capes. Reaching Norfolk the following day, she tarried there until heading out to sea on the evening of 1 September. Giving the Atlantic Fleet, then on maneuvers on the Southern Drill Grounds, a wide berth, Discoverer steered south to Kingston, Jamaica, and steamed thence across the Gulf of Mexico, conducting sampling and surveying work along the way.

Transiting the Panama Canal on 8 October 1922, Discoverer then proceeded up the coast and reached San Diego, Calif., shortly after midnight on 27 October. Working out of San Diego, San Francisco, and Oakland, Discoverer frequented the waters of southern California for the rest of the year 1922 and the early portion of 1923 engaged in coastal survey work.

Discoverer, which would operate in Alaskan waters through the summer of 1925, interspersing periods of “field work” with upkeep at Seattle or San Francisco, began her service in those northern climes in a most notable fashion. While underway for the port of Uyak, Alaska, on 6 June 1923, she picked up an SOS from the minesweeper Cardinal (AM-6), stranded on the rocks off the southern end of Chirikof Island the previous night. She and the oiler Cuyama (AO-3) set course to reach the scene of the grounding.

Discoverer arrived first at 9:50 p.m. on 6 June 1923. Training her searchlight on the stranded minesweeper, Discoverer attempted to launch a whaleboat, but the moderately rough seas to windward of the ship forced her to abandon the attempt. She upped-anchor and crept ahead at 2225, maneuvering to make a lee for the whaleboat, until she struck a rock seven minutes later. Lt. Cmdr. Seran immediately ordered full speed astern, and his ship backed to a position half a mile from where she had touched, letting go her anchor in 13 fathoms.

Discoverer made no further attempt to reach Cardinal that night, but, the following morning, with the sea moderating, she lowered a whaleboat commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Clem L. Garner, USCGS, her executive officer,. The boat proceeded to the stranded minesweeper and returned with 17 of her men. Meanwhile, Cuyama arrived on the scene and radioed the surveying ship that she (Cuyama) could take the remaining men off Cardinal, who numbered three officers (including the commanding officer) and 13 men. Nine of Cardinal’s men were originally unaccounted for, but Discoverer located them soon thereafter safe and sound.

Lt. Cmdr. Garner and eight men, using a motor whaleboat and a motor sailing launch, brought off the remaining Cardinal sailors from their perch ashore. Later that afternoon, Discoverer transferred the shipwrecked ratings to Cuyama. Rear Adm. Jehu V. Chase, Commander Fleet Base Force, later praised Lt. Cmdr. Seran and his crew for their “timely and efficient aid” to the stranded Cardinal. “Your prompt action in reply to this call for assistance,” Chase declared, “prior to the possible time of arrival of the U.S.S. Cuyama,” was rendered in accordance with the best traditions of that brotherhood of “men that go down to the sea in ships.”

Completing her tour of duty in Alaskan waters by late September 1925, Discoverer proceeded south and arrived at San Francisco on 10 October. Two days later, she shifted to Oakland where she underwent voyage repairs and prepared for her next deployment, getting underway for the Hawaiian Islands three days after Christmas of 1925 and reaching Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, on 5 January 1926. The ship conducted hydrographic and topographic surveys of the Hawaiian chain, ranging as far as French Frigate Shoals and Lisianski Island, near Midway, through the late summer of 1927. That proved to be the ship’s only tour in this area of the world, since she resumed operations in Alaskan waters the following spring.

For the next 14 years, Discoverer continued to explore the topography and hydrography of the Alaskan coastline. Each spring she would proceed north from Seattle and commence her work which lasted through the summer and into the fall. Then the ship would return to Seattle for routine upkeep and maintenance while her officers and men plotted the data gathered during previous operations on the “working grounds” and wrote reports of the work conducted. The ship’s ports of call included, among others, Kodiak, Seward, and Dutch Harbor, and the lesser known places such as False Pass, Tigalda Bay, Spruce Island, and Three Brothers’ Reef. Due to the Aleutian chain’s increasing importance to commerce and aviation, as well as to national defense, Discoverer and the other ships in the Coast and Geodetic Survey assigned to that area maintained vigorous charting and mapping operations as the United States edged cautiously toward war.

With the expansion of the U.S. Navy during this time between the outbreak of war in Europe and the entry of the United States into the conflict (1939 to 1941), that service cast about for auxiliaries to support the growing number of combatant ships. One of the ships the Navy now sought was Discoverer, and the Executive Order of 19 June 1941 authorized the Navy to take her over for service as a salvage vessel. The ship concluded her last operations with the Coast and Geodetic Survey in the summer of 1941, having worked out of Dutch Harbor, Cold Bay, Women’s Bay, and Kodiak since the previous spring, and departed Ketchikan on 22 July 1941, bound for Seattle and turnover to the Navy.

Arriving at Seattle on 25 July 1941, Discoverer, the retention of her name by the Navy approved on 5 August 1941, shifted to Pier 41, Seattle on the afternoon of 26 August. There, at 1440, Lt. Cmdr. Erick G. Froberg, D-V(S), USNR, accepted custody of the ship.

Assigned to the Lake Union plant, at Seattle, in October 1941 for degaussing and conversion, Discoverer, classified as ARS-3, underwent a metamorphosis over the next few months, the work still in progress when the Japanese attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

Delivered to the well-known salvage firm of Merritt-Chapman & Scott Corp. who were to operate the vessel under a contract let by the Bureau of Ships, on 16 February 1942, Discoverer was based in familiar waters throughout hostilities with Japan, her ports of call including Kodiak, Dutch Harbor, Cold Bay, Nome, and Women's Bay.

Highlighting this duty was the assistance rendered to the Coast Guard-manned transport Arthur Middleton (AP-55) that had run aground while rescuing survivors from the wrecked destroyer Worden (DD-352) which had herself run aground at Amchitka on 12 January 1943. Ironically, after bearing an almost charmed life while in the Coast Survey, operating in the tricky waters of the Alaskan coastline, Discoverer sustained serious bottom damage when she grounded off the coast of Prince Rupert Island on 20 November 1943 and required assistance from Tatnuck (AT-27), the latter arriving in Prince Rupert harbor during the second dog watch on the 24th and mooring alongside.

Tatnuck got underway for Seattle the following morning (25 November 1943) with Discoverer in tow (an evolution interrupted by the towing bridle carrying away early in the passage), but later, during the first watch, moved the salvage vessel alongside the Canadian Fishing Co. dock at Butedale, British Columbia (B.C.), to wait for the fog to lift. Underway once more the next day, the tug and her tow again encountered heavy fog, forcing them to anchor in Elk Bay, B.C., overnight. Resuming the voyage less than a half hour after the conclusion of the mid watch on 27 November, Tatnuck delivered Discoverer to Pier 40, Seattle, early the following morning [28 November].

Following repairs, Discoverer remained with Merritt-Chapman & Scott into 1946. After it had been recommended on 18 November 1946 that the ship be stricken from the Navy List and turned over to the U.S. Maritime Commission for “disposal as a usable vessel,” indicating that to some the venerable minesweeper/survey ship/salvage vessel still had some years left, Discoverer was withdrawn from service the day after Christmas of 1946, and her name was stricken from the Navy List on 28 January 1947.

Exactly what happened next is not clear. One source indicates that the ship was accepted by the Maritime Commission at Port Nordland, Wash., and delivered to her purchaser, J. W. Rumsey, on 9 June 1947. Another source, however, gives the 9 June 1947 date, but lists the ship as sold to the government of Venezuela. Renamed Felipe Larrazabal (R-11), ex-Discoverer, ex-Auk, appeared in contemporary naval publications into the 1960s. Eventually decommissioned around 1962, the well-traveled vessel was photographed, well down by the stern and rust-streaked, as late as 2015.

Robert J. Cressman

Updated, 20 January 2022